Abstract

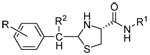

We have previously reported substituted 2-aryl-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid amides as potent and selective antiproliferative agents for melanoma. To understand the importance of the thiazolidine ring and to reduce potential complications associated with the two chiral centers, we designed and synthesized sets of new analogs by modifying this ring. These new analogs were tested in two melanoma cell lines and fibroblast cells (negative controls). Compared with the older analogs containing the thiazolidine ring, these new analogs have lower potency in general, but some of these analogs still have very good selectivity. These structure activity studies indicated that the thiazolidine ring is very critical for the activity for these series of compounds.

While most early stage melanoma can be cured surgically, melanoma cells that have migrated to other organs are notoriously resistant to all existing treatments. The 5-year survival rate for patients with metastatic melanoma is less than 15%.1–4

In the arena of chemotherapeutic agents for advanced melanoma, Dacarbazine (DTIC) is the only FDA-approved drug in the past 30 years. However, it provides only less than 5% of complete remission in patients.3, 5 Significant research and effort have resulted in many promising drug candidates,6 either small molecules or biological agents based on initial small clinical trials; unfortunately, to date none has demonstrated a clear advantage over DTIC in subsequent large, randomized clinical trials.1, 7–11 With the incidence of melanoma rapidly rising in the United States and other developed countries, there is an urgent need to develop more effective drugs.6, 12, 13

We recently reported that substituted 2-aryl-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid amides are promising potent and selective antiproliferative agents for melanoma.14, 15 Compared with Sorafenib that has been used in clinical trials for melanoma, this class of compounds is more potent and more selective based on in vitro cell assays. We demonstrated that the activity of these compounds strongly depends on the length of the side chain and the nature of the substitutions on the aromatic ring. In addition, we found that the chirality at position 4 in thiazolidine analogs is not critical for their activity.14 However, the importance of chirality at position 2 is unknown, because all our previous compounds were tested as diastereomers. Separation of these stereoisomers by chromatographic methods turned out to be extremely difficult. We asked for assistance from scientists from Chiralcel Technologies who tried both normal-phase and reverse-phase conditions with their nine chiral columns, but none of the combinations could separate these stereoisomers satisfactorily (unpublished data).

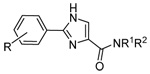

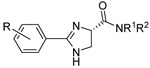

Converting the thiazolidine ring to an imidazoline or imidazole ring represents a very productive approach. First, the nitrogen-containing ring would be very stable. Imidazoline and imidazole rings are important biological building blocks and are present in many existing drugs.16 Second, the imidazoline ring contains only one chiral center, and the imidazole ring contains no chiral center at all. These attributes may alleviate or even eliminate the need for future chiral separations.

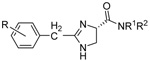

In this paper, we report focused structure activity relationship studies for the central thiazolidine ring, the effect of spacers, and an attempt to remove the chiral centers. Specifically, we modified the structures by a) replacing sulfur with nitrogen or carbon to understand the importance of the heteroatom in the ring, b) introducing one or two double bonds in the ring (imidazoline and imidazole) to understand the importance of the chiral centers, and c) introducing various spacers between the five-member ring and the aromatic ring to understand the relative spatial arrangements for the two rings.

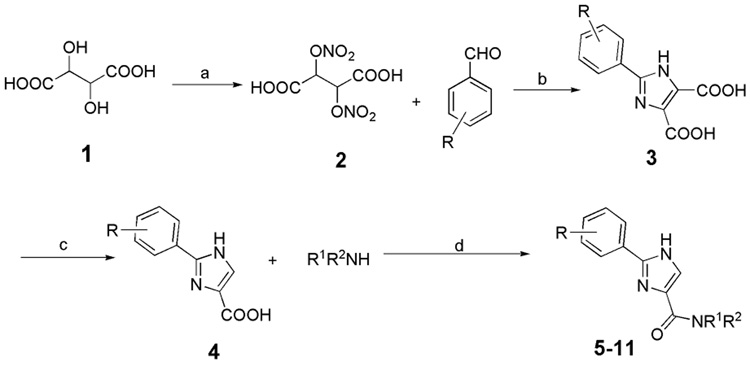

The general synthesis of 2-aryl-imidazole-4-carboxylic acid amides is shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and Conditions: (a) HNO3, H2SO4; (b) NH4OH, H2O; (c) Ac2O, reflux; (d) EDC, HOBt, Et3N, DMF, 0°C-RT

Briefly, L-tartaric acid was converted to a dinitrate that reacted with phenylaldehyde to give 2-phenyl imidazole 4,5-dicarboxylic acid (compound 3) under reported conditions.17 The diacid 3 was converted to monoacid 4 through standard procedures,18 and this monoacid was coupled with alkylamines to give compounds 5–11 by using EDC/HOBt as coupling reagents.19

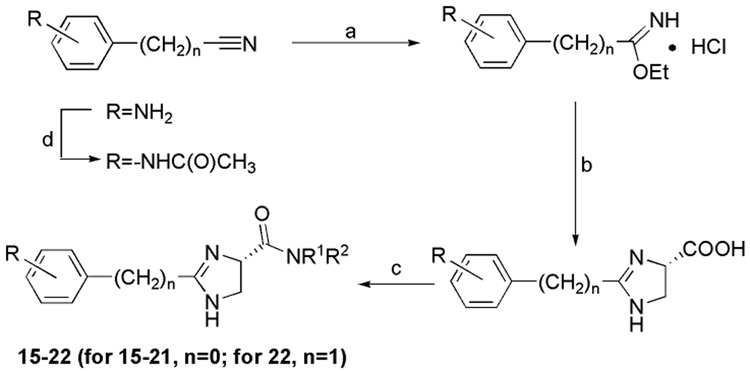

The general synthesis of 2-aryl-imidazoline-4-carboxylic acid amides is shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) HCl, EtOH, ether, 0°C; (b) MeOH, Et3N, (S)-2,3-Diaminopropanoic acid monohydrochloride, reflux; (c) R1R2NH, EDC, HOBt,Et3N, DMF, 0°C-RT; (d) Ac2O, MeOH, RT

Compounds 15–22 were synthesized under reported conditions.20 The intermediate imidate was prepared from corresponding acetonitrile or benzonitrile.21, 22 Then imidate was cyclized with 1,2-Diaminepropionic acid to give the imidazoline monoacid.20 This monoacid coupled with amine to yield the final compounds.

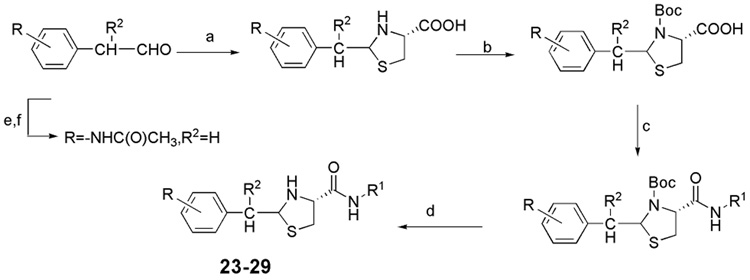

The general synthesis of 2-aryl-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid amides with spacers is shown in Scheme 3. Compounds 23–29 were synthesized by known procedures;14 (p-actylamino)-phenylactaldehyde was prepared from (p-actylamino)-phenylethanol by known procedures;23 (p-actylamino)-phenylethanol was synthesized from (p-amino)-phenylethanol.24

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) L-cysteine, EtOH, H2O, RT; (b) (Boc)2O, NaOH, 1,4-Dioxane, H2O; (c) R1NH2, EDC, HOBt, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0°C-RT; (d) CF3COOH, CH2Cl2; (e) 4-Aminophenethyl alcohol, acetic anhydride, MeOH; (f) Dess-Martin reagent, CH2Cl2

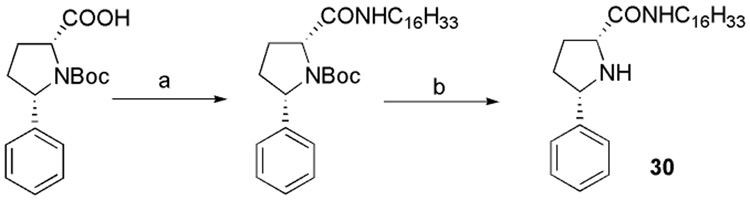

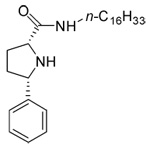

Compound 30, in which sulfur was replaced by a carbon, was obtained by coupling reaction with (2S, 5R)-5-Phenyl-pyrrolidine-1, 2-dicarboxylic acid 1-tertbutyl ester, and hexadecylamine under EDC/HOBt conditions, then deprotection of Boc with TFA yielded 30 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Reagents and conditions: (a) C16H33NH2, EDC, HOBt, Et3N, CH2Cl2; (b) CF3COOH, CH2Cl2 (44.7%, 2 steps)

We examined the antiproliferative activity of these imidazoline and imidazole analogs in two melanoma cell lines (human A375 cells and mouse B16 cells) and in a fibroblast cell line. The activity on fibroblast cells served as a control to determine the selectivity of these compounds against melanoma. We used the standard sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay, which has been shown to provide very reliable results based on the literature25 and our own work 14, 15. Briefly, cells seeded in round-bottom 96-well plates were exposed to a wide range of concentrations for 48 h before they were fixed with 10% trichloroacetic acid. After they were washed five times with water and air-dried overnight, cells were stained with SRB solution, and total proteins were measured at 560 nm with a plate reader. IC50 (i.e., concentration that inhibited cell growth by 50% of DMSO-treated controls) values were obtained by nonlinear regression analysis with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

The ability of these new analogs to inhibit the growth of melanoma cancer cell lines and fibroblast cells is summarized in Table 1. Because of the lack of bioactivation in vitro, DTIC is inactive as expected. We selected Sorafenib (Bay43-9006) as the reference standard, because it has been used extensively in clinical trials for melanoma.6, 26 At this early stage, imidazoline analogs were used as a diastereomeric mixture to select the most promising compounds for further development.

Table 1.

Antiproliferative activity of imidazoline and imidazole analogs and their comparison with that of Sorafenib and the lead thiazolidine compounds (ND: not detected). IC50 values expressed with standard error.

| Structure | Compound | R | R1 | R2 | IC50 ± SEM (µM) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A375 | B16-F1 | Fibroblast | |||||

|

5 | H | n-C10H21 | H | >30 | >30 | ND |

| 6 | H | n-C12H25 | H | >30 | ~30 | ND | |

| 7 | H | n-C14H29 | H | 18.7±1.0 | 38.2±2.1 | 42.7±2.2 | |

| 8 | H | n-C16H33 | H | 16.5±0.6 | 39.7±1.5 | 27.9±1.0 | |

| 9 | H | n-C18H37 | H | 20.7±0.8 | >30 | 47.4±1.3 | |

| 10 | H | (E)-Octadec-8-enyl | H | 16.1±0.5 | 31.6±1.1 | 23.9±1.2 | |

| 11 | H | p-Bromophenyl | H | >30 | >30 | ND | |

|

15 | H | n-C14H29 | H | 7.1±0.1 | 7.2±0.2 | 17.3±2.4 |

| 16 | H | n-C16H33 | H | 10.5±0.2 | 5.7±0.3 | 59.6±1.2 | |

| 17 | H | n-C18H37 | H | 54.3±0.9 | 50.5±1.3 | 111.4±3.8 | |

| 18 | H | (E)-Octadec-8-enyl | H | 8.3±0.2 | 12.0±0.2 | 24.6±2.8 | |

| 19 | 3,4,5-trimethoxyl | OCH3 | CH3 | >20 | >20 | >20 | |

| 20 | 3,4,5-trimethoxyl | n-C16H33 | H | 4.1±0.6 | 3.8±0.1 | 13.3±1.2 | |

| 21 | p-NHCOCH3 | n-C16H33 | H | 4.6±0.1 | 2.4±0.1 | 14.8±1.9 | |

|

22 | 3,4,5-trimethoxyl | n-C16H33 | H | 3.9±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 | 15.8±2.1 |

|

23 | H | n-C16H33 | H | 8.1±1.0 | 6.5±0.1 | 15.3±0.9 |

| 24 | H | (E)-Octadec-8-enyl | H | 10.3±0.5 | 11.6±0.2 | 15.5±1.9 | |

| 25 | H | 2-Fluorene | H | 174±11 | 118±8.0 | >100 | |

| 26 | H | n-C16H33 | CH3 | 13.1±0.5 | 12.2±0.3 | 55.7±7.3 | |

| 27 | H | (E)-Octadec-8-enyl | CH3 | 21.2±0.9 | 16.5±1.0 | 237±39 | |

| 28 | p-NHCOCH3 | n-C16H33 | H | 191±14 | 171±21 | >100 | |

| 29 | p-NHCOCH3 | 2-Fluorene | H | 6.1±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 | 15.3±0.5 | |

|

30 | 13.7±0.4 | 11.5±0.3 | 46.6±1.5 | |||

| DTIC | >100 | >100 | ND | ||||

| Sorafenib | 5.4±0.5 | 4.9±0.3 | 15.1±1.2 | ||||

In general, none of the new analogs is as active as the lead compound. Although they do not contain any chiral centers, analogs containing an imidazole ring (compounds 5–11) did not have activity below 10 µM. Replacing the imidazole ring with an imidazoline ring slightly improved the activity in general (compounds 15–19), with substantial improvement when trimethoxyl or amino acetyl substitutions were added (compounds 20–21). The structure activity for the side chain was similar to that of the thiazolidine analogs, with a saturated C14~C16 chain or an unsaturated C18 chain to be optimal for activity against melanoma cells. Similarly, electronic donating substitutions on the paraposition of the aromatic ring increased activity (compounds 20–21). Replacing sulfur with carbon in the five-member ring produced an inactive compound (30). Collectively, these results indicate that the thiazolidine ring is critical for the activity of this series of compounds.

When a spacer was inserted between the imidazoline/thiazolidine ring and the phenyl ring (compounds 22–29), there is no noticeable improvement in their activity (compound 20 vs. compound 22). Increasing the size of the spacer by replacing one hydrogen in the methylene group with a methyl group reduced the activity (compound 23 vs. 26, and compound 24 vs. 27). Both of these results seemed to indicate detrimental effects of spacers for the activity. Finally, replacing the side chain with a fluorene group resulted in complete loss of activity (compound 23 vs. 25). However, with proper parasubstitution on the aromatic ring, the activity dramatically improved (compound 25 vs. compound 29) for this series of compounds. On the other hand, with a C16 side chain, the substitution on the phenyl ring had the opposite effect (compound 23 vs. 26) in sharp contrast to the nonchain analogs such as 29 and may indicate a different mechanism of action when the long side chain is replaced by a conjugated ring system.

In conclusion, we synthesized new thiazolidine analogs, based on our previous studies, by focusing on the structure activity relationship studies of the central five-member ring. Although the current compounds displayed lower potency when compared with our lead thiazolidine analogs, they may have the distinct advantage of being more stable in vivo with the reduced necessity of chiral separations. Some of these new compounds have activity similar to Sorafenib. Further modification of these compounds to improve their potency is currently in progress. Our ultimate goal is to identify several compounds that are highly potent, are highly selective against melanoma cells, and have very promising ADME characteristics for subsequent in vivo studies.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by funds from the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Tennessee Health Science Center; NIH/NCI 1R15CA125623-01A2 (WL); and the Van Vleet Endowed Professorship (DDM). Zhao Wang acknowledges the support of the Alma and Hal Reagan Fellowship. We thank Dr. David Armbruster for his editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Notes

- 1.Atallah E, Flaherty L. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2005;6:185. doi: 10.1007/s11864-005-0002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson CM, Buzaid AC, Legha SS. Oncology (Williston Park) 1995;9:1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gogas HJ, Kirkwood JM, Sondak VK. Cancer. 2007;109:455. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serrone L, Zeuli M, Sega FM, Cognetti F. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2000;19:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray-Schopfer V, Wellbrock C, Marais R. Nature. 2007;445:851. doi: 10.1038/nature05661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young AM, Marsden J, Goodman A, Burton A, Dunn JA. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2001;13(6):458. doi: 10.1053/clon.2001.9314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandara M, Nortilli R, Sava T, Cetto GL. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:121. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eggermont AM, Kirkwood JM. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1825. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranson M, Hersey P, Thompson D, Beith J, McArthur GA, Haydon A, Davis ID, Kefford RF, Mortimer P, Harris PA, Baka S, Seebaran A, Sabharwal A, Watson AJ, Margison GP, Middleton MR. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2540. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larkin JM, Hughes SA, Beirne DA, Patel PM, Gibbens IM, Bate SC, Thomas K, Eisen TG, Gore ME. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garbe C, Eigentler TK. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:117. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e328042bb36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koon HB, Atkins MB. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:79. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Lu Y, Wang Z, Dalton JT, Miller DD. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:4113. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Wang Z, Gududuru V, Zbytek B, Slominski AT, Dalton JT, Miller DD. Anticancer Research. 2007;27:883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams DA, Lemke TL. Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Fifth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson WK, Bhattacharjee D, Houston DM. J Med Chem. 1989;32:119. doi: 10.1021/jm00121a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis DP, Kirk KL, Cohen LA. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 1982;19:253. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gududuru V, Hurh E, Dalton JT, Miller DD. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2584. doi: 10.1021/jm049208b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergeron RJ, Wiegand J, Weimar WR, Vinson JR, Bussenius J, Yao GW, McManis JS. J Med Chem. 1999;42:95. doi: 10.1021/jm980340j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu FL, Hamada A, Booher ME, Fuder H, Patil PN, Miller DD. J Med Chem. 1980;23:1232. doi: 10.1021/jm00185a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calcinari R, Case N, Guerrato A, Milanino R, Passarella E, Perchinunno M, Tamburini B, Sparatore F. J Med Chem. 1981;24:632. doi: 10.1021/jm00137a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wirt U, Frohlich R, Wunsch B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:2199. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawada Y, Kayakiri H, Abe Y, Mizutani T, Inamura N, Asano M, Aramori I, Hatori C, Oku T, Tanaka H. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2667. doi: 10.1021/jm030326t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dothager RS, Putt KS, Allen BJ, Leslie BJ, Nesterenko V, Hergenrother PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8686. doi: 10.1021/ja042913p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisen T, Ahmad T, Flaherty KT, Gore M, Kaye S, Marais R, Gibbens I, Hackett S, James M, Schuchter LM, Nathanson KL, Xia C, Simantov R, Schwartz B, Poulin-Costello M, O'Dwyer PJ, Ratain MJ. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:581. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]