Abstract

Pneumonia virus of mice (PVM; family Paramyxoviridae, genus Pneumovirus) is a natural mouse pathogen that is closely related to the human and bovine respiratory syncytial viruses. Among the prominent features of this infection, robust replication of PVM takes place in bronchial epithelial cells in response to a minimal virus inoculum. Virus replication in situ results in local production of proinflammatory cytokines (MIP-1α, MIP-2, MCP-1 and IFNγ) and granulocyte recruitment to the lung. If left unchecked, PVM infection and the ensuing inflammatory response ultimately lead to pulmonary edema, respiratory compromise and death. In this review, we consider the recent studies using the PVM model that have provided important insights into the role of the inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of severe respiratory virus infection. We also highlight several works that have elucidated acquired immune responses to this pathogen, including T cell responses and the development of humoral immunity. Finally, we consider several immunomodulatory strategies that have been used successfully to reduce morbidity and mortality when administered to PVM infected, symptomatic mice, and thus hold promise as realistic therapeutic strategies for severe respiratory virus infections in human subjects.

Keywords: inflammation, granulocyte, chemokine, lymphocyte, epithelial

Introduction

There is no one animal model that can replicate all facets and features of a human disease. This is particularly true when considering infectious pathogens, many of which have particular tropisms or specificities for a limited range of hosts, and in some cases present with completely different clinical illnesses in different species. While it would be perhaps ideal to study all human pathogens in natural, relevant human or higher primate hosts, ethical limitations and overall impracticalities preclude this approach. Despite clear and recognized differences between human and rodent immune and inflammatory responses, various factors, including availability of characterized strains, ease of handling and breeding, availability of sophisticated genetic and molecular tools, and an extraordinary amount of pre-existing data, have together provided a focus on inbred strains of mice as a centerpiece for human disease research. As such, it is critical that the unique features of each infectious disease model are presented effectively so that specific advantages and individual limitations in each situation are clearly understood.

With this in mind, we have undertaken an exploration of the pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) pathogen for the study of respiratory virus replication and the ensuing inflammatory response within a natural, evolutionarily relevant host-pathogen relationship. PVM is closely related to the human pathogen, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and although there is little direct amino acid sequence homology between virus-encoded proteins, PVM has the advantage of undergoing robust replication and eliciting symptomatic disease in response to a minimal virus inoculum in inbred strains of mice. Indeed, PVM infection in mice reproduces many of the clinical and pathologic features of the more severe forms of RSV infection in human infants. With this model, we have highlighted the importance of the virus-induced inflammatory responses as contributing to the more severe sequelae associated with this disease as well as provided an explanation for the minimal impact of antiviral administration in this clinical setting. Furthermore, we have designed several immunomodulatory strategies that have been effective at reducing morbidity and mortality when administered to mice already symptomatic with established virus infection.

History

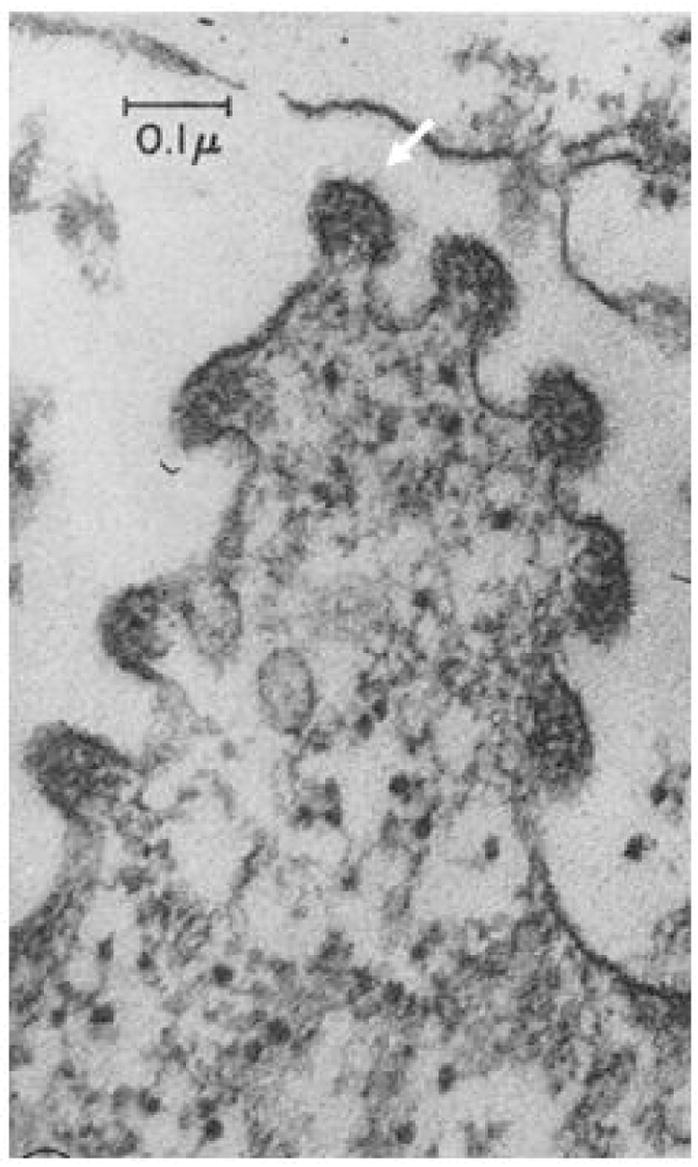

Although interest in this pathogen has re-emerged only recently, PVM was originally discovered in 1939 by researchers Horsfall and Hahn at The Rockefeller University as part of an attempt to identify pathogens from human clinical samples that would replicate in lung tissues of inbred mice [1]. Interestingly, PVM was isolated from lung tissue from the control (presumably uninfected) mice, which yielded an infectious isolate after undergoing serial mouse-to-mouse passage. Choppin and colleagues [2] presented the first electron micrographs of these newly discovered virions [Figure 1], which they described as defining a new, third subgroup of myxoviruses. The polymorphic virions formed spheres of 80 – 120 millimicrons in diameter to filaments up to three microns in length, and replicated over a period of 24 – 30 hours in mouse lung tissue in vivo, with virus amplification proceeding at ~16-fold per cycle. Perhaps most interesting, Ginsberg and Horsfall [3] recognized the potential of PVM for the exploration of acute respiratory virus infection in an evolutionarily relevant host. Among several studies, these authors were the first to relate the development of lung lesions to ongoing virus replication and to evaluate altered morbidity and mortality in response to rudimentary immumodulatory therapy, specifically in response to administration of bacterial capsular polysaccharide [3 –5].

Figure 1. Electron microscopic image of nascent PVM virions.

Virions as shown budding (at arrow) from BHK-21 cells in culture. Reprinted with permission from Compans RW et al. [2].

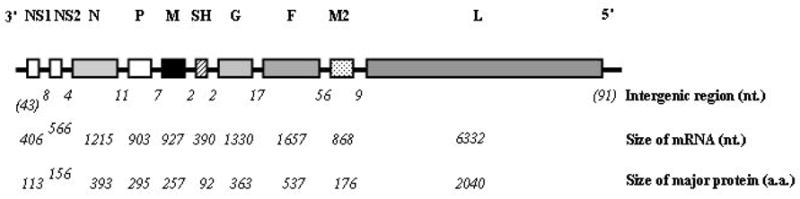

Genomic Organization of PVM

PVM, along with human and bovine RSV, are viruses of the family Paramyxoviridae, subfamily Pneumovirinae, which are enveloped, negative sense, single-stranded RNA viruses [6]. The molecular organization of the PVM genome has been elucidated primarily by Easton and colleagues [7 – 10], and has been the subject of several recent reviews [11, 12]. The genomic organization of PVM is shown in Figure 2, in which the 3′ to 5′ gene order, the genome size (~15 kB), and the sizes of the coding sequences and the intergenic regions are displayed.

Figure 2. Genomic organization of PVM.

Shown are the 3′ to 5′ linear order of PVM protein encoding genes, including non-structural proteins (NS1 and NS2), nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), surface hydrophobic protein (SH), attachment protein (G), fusion protein (F), the M2 genes, and polymerase protein (L). The sizes of the intergenic and coding sequences in nucleotides (nt) and the number of encoded amino acids (aa) are as shown. Reprinted with permission from Rosenberg HF et al. [11].

Pathogenic and Attenuated Strains of PVM

There are two main characterized strains of PVM in general use, although there is not complete clarity on all related details. The original studies by Horsfall and colleagues [1, 3 – 5] were performed on an isolate known as strain 15, which was at that time highly pathogenic in mice. Since that time, the PVM strain 15 has reportedly undergone tissue culture passage, thus losing some of its pathogenicity in vivo, although the extent to which this is so, and in which specific isolates, remains uncertain. A second strain, PVM strain J3666, also developed at the Rockefeller University, has been reportedly maintained in mice with minimal tissue-culture passage, and has recently been shown to be highly pathogenic in nearly all inbred strains of mice [13]. In our hands, PVM strain 15 from Dr. Andrew Easton’s laboratory (PVM strain 15 Warwick) is highly attenuated and elicits a minimal inflammatory response in the highly susceptible BALB/c strain of mice [14]. In contrast, PVM strain 15 from the American Type Culture collection (PVM strain 15 ATCC) is pathogenic in BALB/c mice (unpublished findings), but results in little to no disease in the less susceptible C57BL/6 strain at similar inoculating doses (<100 pfu/mouse [15]). Krempl and colleagues [16] likewise found PVM strain 15 (ATCC) to be highly pathogenic in the BALB/c strain. Complete sequence data are available for both PVM strain J3666 and PVM strain 15 [17, 18]. The most remarkable differences are in selected regions of the G (attachment protein) which may contribute to its differential virulence [16], and throughout the sequence of the SH small hydrophobic glycoprotein.

Recombinant PVM

Two groups have reported success at generating a replicating form of recombinant PVM using a reverse genetics approach [19 – 21]. Using this system, Easton and colleagues [19, 20] have explored the roles of the virus M2-1, M2-2, and P open reading frames of PVM strain 15 (Warwick) in supporting reporter gene activity in vitro and have evaluated the plasticity of the transcriptional start sites. Buchholz and colleagues [21] determined that the full G (attachment) protein was crucial for replication of PVM strain 15 (ATCC) in vivo while the G protein cytoplasmic tail alone promoted weight loss.

Inflammatory Responses and Disease Severity

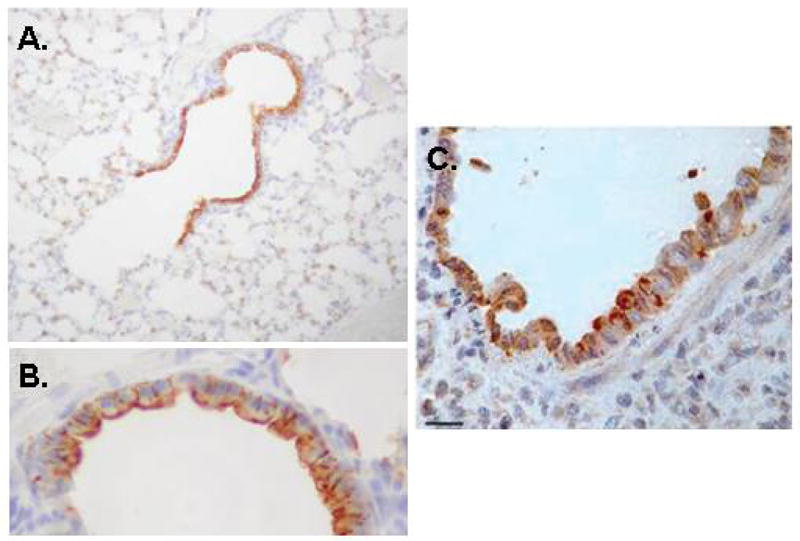

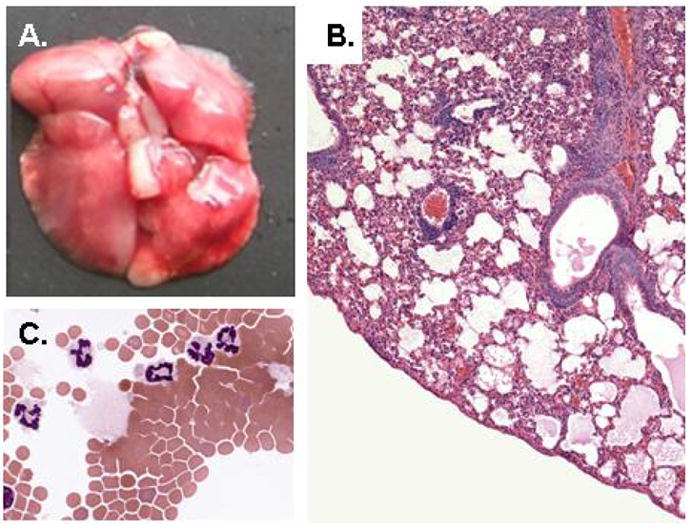

We became interested in PVM in order to pursue studies of inflammatory responses to respiratory virus infections in a natural, evolutionarily-relevant host. We initially recapitulated the aforementioned findings of Horsfall and colleagues and reported robust virus replication in situ (to titers as > 108 pfu/gm lung tissue), progressing to marked morbidity (hunching, fur ruffling), weight loss, and mortality, in our case in response to a minimal virus inoculum of the highly pathogenic strain PVM J3666 [22, 23]. We have localized immunoreactive PVM to the bronchiolar epithelium [24], in a distribution similar to what has been observed for RSV in human post-mortem specimens [25; Figure 3]. Microscopic examination of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and lung tissue from morbid mice revealed profound inflammation, most notable for recruitment of granulocytes and for severe pulmonary edema consistent with the clinical findings characteristic of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS; Figure 4). Interestingly, severe inflammation, edema and recruitment of granulocytes have also been characterized in a recent series of RSV-diagnosed post-mortem samples evaluated by Welliver and colleagues [25]. PVM replication in situ results in local production of proinflammatory mediators, including MIP-1α, MIP-2, MCP-1 and IFNγ [24]. A similar subset of proinflammatory mediators is produced in association with the more severe forms of RSV in human infants [reviewed in 6].

Figure 3. Detection of immunoreactive PVM and RSV in bronchiolar epithelial cells.

(A) Immunoreactive PVM is detected in infected mouse lung tissue by probing with convalescent mouse sera, original magnification 20X, (B) as in (A), original magnification 40X. (C) Detection of immunoreactive RSV in post-mortem human lung tissue, original magnification 40X. PVM images reprinted with permission from Bonville CA et al., [24]; RSV images reprinted with permission from Welliver TP et al., [25].

Figure 4. Lung pathology.

(A) Lung tissue from infected mice, with region of typical grey discoloration and multiple hemorrhagic foci; reprinted with permission from Ellis JA et al., [15]; (B) Microscopic pathology, with evidence of profound cellular inflammatory response and developing pulmonary edema; original magnification, 20X, reprinted with permission from Garvey TL et al., [38] (C) Broncho-alveolar lavage fluid, with recruited neutrophils, original magnification, 63X.

MIP-1α (CCL3) is a crucial component of the virus-induced inflammatory response

Similar to findings from the mouse model of influenza virus [26] we found that the chemokine, MIP-1α (CCL3), is crucial for granulocyte recruitment in response to PVM infection [23]. Specifically, MIP-1α gene-deleted mice are readily infected with PVM, although 105-fold fewer granulocytes are recruited to the lung tissue in response to the identical initial inoculum. Similar results were obtained upon infecting mice devoid of CCR1, the major receptor for MIP-1α on neutrophils and eosinophils. We have used this observation to design specific immunomodulatory strategies for the virus-induced inflammatory response and its associated pathology (discussed further below; [27, 28]). Interestingly, although MIP-1α is clearly crucial for granulocyte recruitment in response to PVM infection, this chemokine, acting alone, even at high concentrations, does not induce ARDS, nor does it recruit granulocytes effectively in the absence of IFNγ (Bonville et al., manuscript in preparation).

Inflammatory responses in aged mice

Respiratory virus infection is also a growing problem in the aging population [29]. In a study performed using young adult (8 – 12 weeks) through aged (up to 78 weeks) but otherwise immunologically naïve mice, we observed no change in the kinetics of PVM replication, but diminished local production of several proinflammatory mediators, including MIP-1α, MCP-1, and IFNγ, along with diminished recruitment of granulocytes to the lung tissue [30]. The differences observed when comparing these results to those reported among elderly human subjects, who tend to have more severe, rather than less severe forms of RSV infection, may be related to virus re-exposure and its impact on the ensuing biochemical and cellular inflammatory responses. Interestingly, there is no published data on PVM replication and disease pathogenesis in neonatal mice, a critical target population given the prevalence of pneumovirus infection among human infants and toddlers.

Role of TLR4

There exists a controversy in the literature as to whether or not the toll-like receptor, TLR4, has any role to play in providing host defense against respiratory virus infection [31, 32]. Specifically with respect to respiratory syncytial virus, Kurt-Jones and colleagues [31] reported prolonged detection of virions in lung tissue of TLR4-gene-deleted C57BL/10ScCr strain of mice. Subsequent studies documented the existence of a point mutation in the IL-12Rβ2 rendering this background strain unresponsive to IL-12 [33], and, as an attempt to discern among the possibilities, Ehl and colleagues [32] determined that it was the lack of IL-12 response, rather than the TLR4 gene-deletion, that resulted diminished RSV-specific T cell immunity. In order to address this issue somewhat further, Desmecht and colleagues [34] compared the responses of wild type and TLR4 gene-deleted mice to infection with PVM. No differences in virus replication, weight loss, pulmonary function or histology were observed, consistent with results obtained by van der Poll and colleagues [35] who studied the responses to Sendai virus, another natural pathogen. Taken together, these results suggest that TLR4 actually does not have a crucial, indispensable function in promoting host defense against a natural respiratory virus infection. However, other pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLR3 [36], TLR7 [37]) have been explored vis à vis their role in promoting host defense against respiratory syncytial virus challenge, and might be intriguing subjects for future study with the natural PVM pathogen model.

Differential responses in type I IFN receptor gene-deleted mice

Pneumoviruses have unusual anti-interferon strategies, as they do not limit IFN production, nor do they interfere with receptor binding or signal transduction. Of particular recent interest are the ways in which IFNs and IFN-mediated signaling mechanisms interact with proinflammatory pathways and modulate the production of chemoattractant cytokines. As part of a larger exploration of the inflammatory responses to PVM, we examined the differential expression of cytokine genes in wild type mice and mice devoid of the receptor for type I interferons (IFNαβR gene-deleted mice; [38]). As anticipated, PVM infection induces transcription of IFN antiviral response genes preferentially in lung tissue of wild-type over IFNαβR gene-deleted mice. However, we demonstrate that PVM infection also results in enhanced expression of eotaxin-2, TARC, and the proinflammatory RNase mouse eosinophil-associated RNase (mEar) 11, and we observe paradoxically prolonged survival among the IFNαβR gene-deleted mice.

T lymphocyte responses, Allergy and Immunity

T cell responses

Although the initial cellular response to PVM is virtually all granulocytes, Claassen and colleagues [39] detected a pronounced influx of CD8+ T cells beginning on day 8 in response to a relatively low, non-fatal inoculum. Three PVM-specific T cell epitopes were identified, including one in the P phosphoprotein (P261-269), one in the M matrix protein (M43-51) and one within the F fusion protein (F304-312). Interestingly, the frequency of PVM-specific CD8+ T cells was relatively low, and only ~10 – 20% of the P261-directed CD8+ T cells produced cytokines IFNγ and TNFα in response to appropriate stimulation, a deficient response similar to that characterized for RSV and Sv5 infections [40, 41].

Subsequently, Claassen and colleagues [42] identified a CD4+ T cell epitope, amino acids 381 – 385 within the G glycoprotein of PVM, and demonstrated protective immunity against lethal PVM challenge when mice were immunized simultaneously with both CD4+ and the aforementioned P261 CD8+ T cell epitope peptides; PVM-G specific CD4+ T cells recruited to the lungs produced both IFNγ and IL-5.

Recent data also point to a role for a strong Th17 cellular response in the pathogenesis of PVM infection (Domachowske, unpublished observation).

PVM challenge augments Th2 responses to allergic sensitization and challenge

The role of respiratory virus infection in promoting and exacerbating pre-existing allergic responses is an area of significant research interest [43, 44]. Barends and colleagues [45] demonstrated that PVM, when administered as part of the challenge phase in a standard ovalbumin sensitization/challenge protocol, serves to augment pulmonary Th2 responses over and above that observed in response to ovalbumin alone. Specifically, PVM challenge occurring at the same time with ovalbumin resulted in elevated levels of Th2 cytokine mRNA and associated influx of eosinophils into the lung tissue.

Immunity to PVM generated via mucosal inoculation

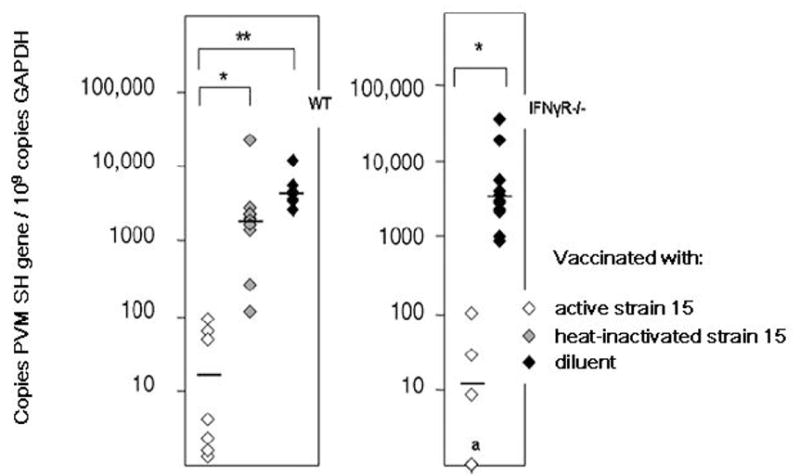

Using PVM strain 15 (ATCC), which is attenuated (replication-competent but does not induce a profound inflammatory response) in the C57BL/6 mouse strain, we explored the development of acquired immunity in response to a mucosal vaccination strategy. Neutralizing antibodies were detected at 14 days after inoculation in mice receiving live attenuated virus (but not heat-inactivated virus), which correlated with protection against subsequent challenge with the highly pathogenic strain J3666 [15]. Among the interesting questions, we are not certain of the duration of protective immunity. Interestingly, the responses of IFNγR gene-deleted mice were indistinguishable from the wild type mice, indicating that any role for IFNγ in generating acquired immunity in this setting is at least somewhat dispensible [Figure 5]. Among our other findings, PVM antigens, when prepared and administered in a manner analogous to the earlier hRSV lot 100 vaccine [46], will induce a Th2-mediated allergic inflammatory response (Percopo et al., manuscript in preparation).

Figure 5. Virus replication in lung tissue of vaccinated mice.

Wild type and IFNγR gene-deleted mice were vaccinated with live-attenuated PVM strain 15 (ATCC), heat-inactivated strain 15, or diluent alone and challenged with virulent strain J3666. Replication was measured by a quantitative RT-PCR assay designed to detect the PVM SH gene. We observed no differences in the kinetics of virus replication, and no differences in responses to mucosal vaccination between the wild type and IFNγR gene-deleted mouse strains. Reprinted with permission from Ellis JA et al., [15].

Therapeutic Strategies

Among the primary reasons to explore respiratory virus infection using the PVM model is to improve our understanding of the molecular basis of severe disease so as to design novel therapeutic strategies.

Antiviral Agents

The antiviral agent, ribavirin, is very effective at blocking replication of RSV both tissue culture and in human subjects, yet the impact of ribavirin therapy alone on the course of actual clinical disease is insignificant [47]. The PVM model replicates this scenario, as ribavirin at concentrations of > 10 μg/ml are effective at blocking virus replication in tissue culture, and at concentrations of 75 μg/kg/day, at blocking virus replication in mouse lung tissue in vivo. Yet, analogous to observations made in clinical studies, administration of effective doses of ribavirin alone to PVM-infected, symptomatic mice, has little impact on the ultimate outcome of disease, when measured in terms of morbidity and mortality [27, 28]. In conjunction with this observation, we found that, although ribavirin was quite effective at blocking virus replication, it had no impact on the ongoing production of proinflammatory chemokines and associated recruitment of granulocytes to the lung tissue. Clearly, there is some disconnect between virus replication and the ensuing inflammatory response, in that inflammation is not necessarily controlled effectively at any given point in time by reducing or eliminating the primary stimulus.

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are in general use as broad spectrum anti-inflammatory agents, yet overall analysis suggests that they have only limited benefit for the treatment of severe hRSV associated inflammation [48]. Although we have not evaluated specific combinations of ribavirin and glucocorticoids in PVM infected mice, we have documented the effects of hydrocortisone alone on the inflammatory response. We have determined that hydrocortisone therapy has no effect on the production of MIP-1α or on the influx of neutrophils; PVM-infected mice responded to hydrocortisone with enhanced viral replication and slightly accelerated mortality [49]. These results suggest several mechanisms to explain why glucocorticoid therapy may be of limited benefit in the overall picture of pneumovirus infection. Interestingly, Thomas and colleagues [50] also determined that glucocorticoids had no impact on the virus-induced chemokine response in hRSV infection in human subjects.

Combination Therapy with Ribavirin and Specific Immunomodulatory Agents

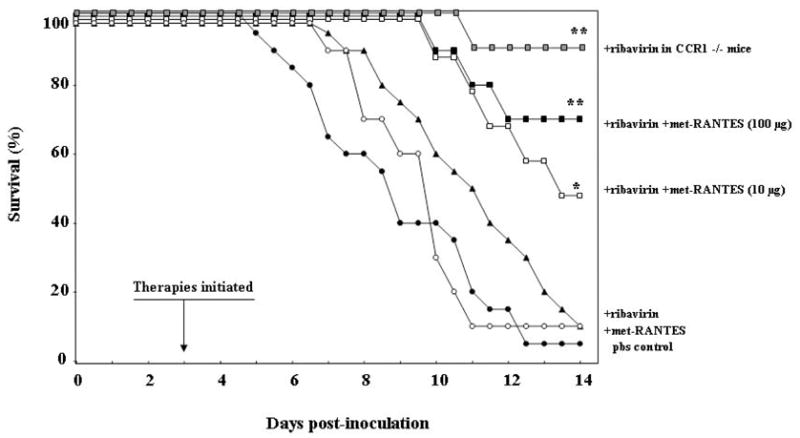

Given our earlier observation on the crucial nature of the chemokine, MIP-1α, in promoting granulocyte recruitment in response to virus infection, we considered the possibility that blockade of this chemokine itself, or its signaling via its major receptor, CCR1, might provide appropriate immunomodulatory control in this setting. In a series of studies, we found significant improvements in long term survival when ribavirin was administered to symptomatic mice in conjunction with anti-MIP-1α antibodies, or with small molecule blockade (met-RANTES) of the MIP-1α receptor, CCR1 [Figure 6; [27, 28]].

Figure 6. Survival of PVM-infected mice treated with combined antiviral and immunomodulatory therapy.

Improved survival resulted from treatment with ribavirin and met-RANTES (* p< 0.05) compared individually to the groups treated with Met-RANTES alone, ribavirin alone, or PBS. Further improvement was observed in response to combination of ribavirin with the higher met-RANTES dose, 100 μg/day, over that observed in response to ribavirin-met-RANTES at 10 μg/day (** p < 0.05), approaching that observed for CCR1 gene-deleted (CCR1 −/−) mice treated with ribavirin, representing theoretical complete receptor blockade. Reprinted with permission from Bonville CA et al., [28].

A similar study documented the effectiveness of ribavirin in conjunction with the cysteinyl-leukotriene inhibitor montelukast [51]. Interestingly, although neither agent was effective at reducing morbidity or mortality as single agent therapy, together, administered to infected, symptomatic mice, significant improvements in long-term survival were observed (50% vs. 10% for PBS control). Interestingly, montelukast had little impact overall on neutrophil recruitment, suggesting that the presence of neutrophils alone does not indicate inevitable progression to intractable disease.

Conclusions

The PVM model holds great promise for the elucidation of inflammatory mechanisms associated with virus infection and acute inflammatory responses in the lung. Studies carried out to date have provided an explanation for the lack of clinical efficacy of antiviral therapy, and have indicated that chemokine and/or chemokine receptor blockade in conjunction with appropriate antiviral therapy might be more effective than antiviral therapy alone. Likewise, PVM is an excellent system in which to explore the molecular mechanisms via which natural immunity to pneumovirus infection develops, information which may assist in the development of novel vaccines and other prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

Ongoing work in our laboratories is supported by the New York Children’s Miracle Network (to JBD) and NIAID Division of Intramural Research (to HFR).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Horsfall FL, Hahn RG. A latent virus in normal mice capable of producing pneumonia in its natural host. J Exp Med. 1940;71:391 – 408. doi: 10.1084/jem.71.3.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compans RW, Harter DH, Choppin PW. Studies on pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) in cell culture. II. Structure and morphogenesis of the virus particle. J Exp Med. 1967;126:267–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.126.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horsfall FL, Ginsberg HS. The dependence of the pathological lesion upon the multiplication and extent of pneumonia. J Exp Med. 1951 Feb;93(2):139–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.93.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsberg HS, Horsfall FL., Jr Therapy of infection with pneumonia virus of mice (PVM); effect of a polysaccharide on the multiplication cycles of the virus and on the course of the viral pneumonia. J Exp Med. 1951;93:161–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.93.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsberg HS, Horsfall FL., Jr Concurrent infection with influenza virus and mumps virus or pneumonia virus of mice as bearing on the inhibition of virus multiplication by bacterial polysaccharides. J Exp Med. 1949;89:37–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.89.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Easton AJ, Domachowske JB, Rosenberg HF. Animal pneumoviruses: molecular genetics and pathogenesis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:390–412. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.2.390-412.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers P, Pringle CR, Easton AJ. Sequence analysis of the gene encoding the fusion glycoprotein of pneumonia virus of mice suggests possible conserved secondary structure elements in paramyxovirus fusion glycoproteins. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1717–24. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-7-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barr J, Easton AJ. Characterisation of the interaction between the nucleoprotein and phosphoprotein of pneumonia virus of mice. Virus Res. 1995;39:221–35. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Easton AJ, Chambers P. Nucleotide sequence of the genes encoding the matrix and small hydrophobic proteins of pneumonia virus of mice. Virus Res. 1997;48:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(96)01430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmadian G, Chambers P, Easton AJ. Detection and characterization of proteins encoded by the second ORF of the M2 gene of pneumoviruses. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2011–6. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg HF, Bonville CA, Easton AJ, Domachowske JB. The pneumonia virus of mice infection model for severe respiratory syncytial virus infection: identifying novel targets for therapeutic intervention. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Easton AJ, Domachowske JB, Rosenberg HF. In: Pneumonia Virus of Mice, in Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Perspectives in Medical Virology. Cane P, editor. Vol. 14. Amsterdam: Elsevier Press; pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anh DB, Faisca P, Desmecht DJ. Differential resistance/susceptibility patterns to pneumovirus infection among inbred mouse strains. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L426–35. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00483.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domachowske JB, Bonville CA, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF. Differential expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes in vivo in response to pathogenic and nonpathogenic pneumovirus infections. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:8–14. doi: 10.1086/341082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis JA, Martin BV, Waldner C, Dyer KD, Domachowske JB, Rosenberg HF. Mucosal inoculation with an attenuated mouse pneumovirus strain protects against virulent challenge in wild type and interferon-gamma receptor deficient mice. Vaccine. 2007;25:1085–95. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krempl CD, Collins PL. Reevaluation of the virulence of prototypic strain 15 of pneumonia virus of mice. J Virol. 2004;78:13362–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13362-13365.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorpe LC, Easton AJ. Genome sequence of the non-pathogenic strain 15 of pneumonia virus of mice and comparison with the genome of the pathogenic strain J3666. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:159–69. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krempl CD, Lamirande EW, Collins PL. Complete sequence of the RNA genome of pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) Virus Genes. 2005;30:237–49. doi: 10.1007/s11262-004-5631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dibben O, Easton AJ. Mutational analysis of the gene start sequences of pneumonia virus of mice. Virus Res. 2007;130:303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dibben O, Thorpe LC, Easton AJ. Roles of the PVM M2-1, M2-2 and P gene ORF 2 (P-2) proteins in viral replication. Virus Res. 2008;131:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krempl CD, Wnekowicz A, Lamirande EW, Nayebagha G, Collins PL, Buchholz UJ. Identification of a novel virulence factor in recombinant pneumonia virus of mice. J Virol. 2007;81:9490–501. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00364-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domachowske JB, Bonville CA, Dyer KD, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF. Pulmonary eosinophilia and production of MIP-1alpha are prominent responses to infection with pneumonia virus of mice. Cell Immunol. 2000;200:98–104. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domachowske JB, Bonville CA, Gao JL, Murphy PM, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF. The chemokine macrophage-inflammatory protein-1 alpha and its receptor CCR1 control pulmonary inflammation and antiviral host defense in paramyxovirus infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:2677–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonville CA, Bennett NJ, Koehnlein M, Haines DM, Ellis JA, DelVecchio AM, et al. Respiratory dysfunction and proinflammatory chemokines in the pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) model of viral bronchiolitis. Virology. 2006;349:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welliver TP, Garofalo RP, Hosakote Y, Hintz KH, Avendano L, Sanchez K, et al. Severe human lower respiratory tract illness caused by respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus is characterized by the absence of pulmonary cytotoxic lymphocyte responses. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1126–36. doi: 10.1086/512615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook DN, Beck MA, Coffman TM, Kirby SL, Sheridan JF, Pragnell IB, Smithies O. Requirement of MIP-1 alpha for an inflammatory response to viral infection. Science. 1995;269:1583–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7667639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonville CA, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF, Domachowske JB. Altered pathogenesis of severe pneumovirus infection in response to combined antiviral and specific immunomodulatory agents. J Virol. 2003;77:1237–44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1237-1244.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonville CA, Lau VK, DeLeon JM, Gao JL, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF, Domachowske JB. Functional antagonism of chemokine receptor CCR1 reduces mortality in acute pneumovirus infection in vivo. J Virol. 2004;78:7984–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.7984-7989.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Looney RJ, Falsey AR, Walsh E, Campbell D. Effect of aging on cytokine production in response to respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:682–5. doi: 10.1086/339008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonville CA, Bennett NJ, Percopo CM, Branigan PJ, Del Vecchio AM, Rosenberg HF, Domachowske JB. Diminished inflammatory responses to natural pneumovirus infection among older mice. Virology. 2007;368:182–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurt-Jones EA, Popova L, Kwinn L, Haynes LM, Jones LP, Tripp RA, et al. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:398–401. doi: 10.1038/80833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehl S, Bischoff R, Ostler T, Vallbracht S, Schulte-Mönting J, Poltorak A, Freudenberg M. The role of Toll-like receptor 4 versus interleukin-12 in immunity to respiratory syncytial virus. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1146–53. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poltorak A, Merlin T, Nielsen PJ, Sandra O, Smirnova I, Schupp I, et al. A point mutation in the IL-12R beta 2 gene underlies the IL-12 unresponsiveness of Lps-defective C57BL/10ScCr mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:2106–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faisca P, Tran Anh DB, Thomas A, Desmecht D. Suppression of pattern-recognition receptor TLR4 sensing does not alter lung responses to pneumovirus infection. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:621–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Sluijs KF, van Elden L, Nijhuis M, Schuurman R, Florquin S, Jansen HM, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is not involved in host defense against respiratory tract infection with Sendai virus. Immunol Lett. 2003;89:201–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(03)00138-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groskreutz DJ, Monick MM, Powers LS, Yarovinsky TO, Look DC, Hunninghake GW. Respiratory syncytial virus induces TLR3 protein and protein kinase R, leading to increased double-stranded RNA responsiveness in airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:1733–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phipps S, Lam CE, Mahalingam S, Newhouse M, Ramirez R, Rosenberg HF, Foster PS, Matthaei KI. Eosinophils contribute to innate antiviral immunity and promote clearance of respiratory syncytial virus. Blood. 2007;110:1578–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-071340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garvey TL, Dyer KD, Ellis JA, Bonville CA, Foster B, Prussin C, et al. Inflammatory responses to pneumovirus infection in IFNαβR gene-deleted mice. J Immunol. 2005;175:4735–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Claassen EA, van der Kant PA, Rychnavska ZS, van Bleek GM, Easton AJ, van der Most RG. Activation and inactivation of antiviral CD8 T cell responses during murine pneumovirus infection. J Immunol. 2005;175:6597–604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang J, Braciale TJ. Respiratory syncytial virus infection suppresses lung CD8+ T cell effector activity and peripheral CD8+ T cell memory in the respiratory tract. Nat Med. 2002;8:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gray PM, Arimilli S, Palmer EM, Parks GD, Alexander-Miller MA. Altered function in CD8+ T cells following paramyxovirus infection of the respiratory tract. J Virol. 2005;79:3339–49. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3339-3349.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claassen EA, van Bleek GM, Rychnavska ZS, de Groot RJ, Hensen EJ, Tijhaar EJ, van Eden W, van der Most RG. Identification of a CD4 T cell epitope in the pneumonia virus of mice glycoprotein and characterization of its role in protective immunity. Virology. 2007;368:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukacs NW, Smit J, Lindell D, Schaller M. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced pulmonary disease and exacerbation of allergic asthma. Contrib Microbiol. 2007;14:68–82. doi: 10.1159/000107055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xepapadaki P, Papadopoulos NG. Viral infections and allergies. Immunobiology. 2007;212:453–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barends M, de Rond LG, Dormans J, van Oosten M, Boelen A, Neijens HJ, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus, pneumonia virus of mice, and influenza A virus differently affect respiratory allergy in mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:488–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prince GA, Curtis SJ, Yim KC, Porter DD. Vaccine-enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease in cotton rats following immunization with Lot 100 or a newly prepared reference vaccine. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:2881–8. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ventre K, Randolph AG. Ribavirin for respiratory syncytial virus infection of the lower respiratory tract in infants and young children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD000181. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000181.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel H, Platt R, Lozano JM, Wang EE. Glucocorticoids for acute viral bronchiolitis in infants and young children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:CD004878. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Domachowske JB, Bonville CA, Ali-Ahmad D, Dyer KD, Easton AJ, Rosenberg HF. Glucocorticoid administration accelerates mortality of pneumovirus-infected mice. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1518–23. doi: 10.1086/324664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas LH, Sharland M, Friedland JS. Steroids fail to down-regulate respiratory syncytial virus-induced IL-8 secretion in infants. Pediatr Res. 2002;52:368–72. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonville CA, Rosenberg HF, Domachowske JB. Ribavirin and cysteinyl leukotriene-1 receptor blockade as treatment for severe bronchiolitis. Antiviral Res. 2006;69:53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]