Abstract

Chemical genetics seeks to identify small molecules that afford functional dissection of cell biological pathways. Previous screens for small molecule inhibitors of exocytic membrane traffic yielded the identification and characterization of several compounds that block traffic from the Golgi to the cell surface as well as transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi network. Here, we screened these inhibitors for potential effects on endocytic membrane traffic. Two structurally related sulfonamides were found to be potent and reversible inhibitors of transferrin-mediated iron uptake. These inhibitors do not block endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport, but do disrupt Golgi-to-cell surface traffic. The compounds are members of a novel class of sulfonamides that elevate endosomal and lysosomal pH, down-regulate cell surface receptors, and impair recycling of internalized transferrin receptors to the plasma membrane. In vitro experiments revealed that the sulfonamides directly inhibit adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis by the V-ATPase and that they also possess a potent proton ionophore activity. While maintenance of organellar pH is known to be a critical factor in both endocytosis and exocytosis, the precise role of acidification, beyond the uncoupling of ligands from their receptors, remains largely unknown. Identification of this novel class of sulfonamide inhibitors provides new chemical tools to better understand the function of organelle pH in membrane traffic and the activity of V-ATPases in particular.

Keywords: chemical genetics, membrane traffic, organelle pH, sulfonamides

Chemical genetics seeks to identify novel small molecules that afford functional dissection of cell biological pathways (1–3). Such compounds are useful as bioactive molecular probes and allow further analysis of the relationship between target processes or proteins within cells and their cellular function. We have taken a chemical genetics approach to identify small cell-permeable molecules that block exocytosis (4,5). The exocytic or constitutive secretory pathway encompasses vesicular movement of newly synthesized membrane proteins and secretory components from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi apparatus with final arrival at the cell surface (for resident plasma membrane proteins) or export (for secreted proteins). To identify small molecule inhibitors of this pathway, we employed a medium-throughput screen based on cell fluorescence imaging of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged vesticular stomatitis virus glycoprotein temperature-sensitive mutant (VSV-Gts045) which transits this pathway in a well-defined and experimentally manipulable fashion (4,5). This investigation led to the discovery of Exo1(6B6) and Exo2(15E19), agents that block exit from the ER (4), as well as five other compounds (16D20, 30N12, 4F17, 17G7, 16F19) that block exit from the Golgi (5). To further examine the selectivity of these compounds as inhibitors of specific steps of intracellular membrane traffic, we undertook the present study to explore their effects on the endocytic pathway.

The process of endocytosis brings extracellular material and plasma membrane proteins into cells from their surface through a series of membrane-bound compartments, often referred to as early, sorting and recycling endo-somes. Internalized material is sorted and ultimately directed from these endocytic organelles for degradation in lysosomes or for return to the cell surface (recycling). Our knowledge of the endocytic recycling pathway is largely based on detailed analysis of the membrane traffic of transferrin (Tf). This serum iron-binding protein associates with specific cell surface receptors to be internalized and delivered to the endocytic pathway. These binding interactions are facilitated at the extracellular pH of 7.4 with high ligand binding affinity (Kd ~ 1−5 nm) (6,7). Tf–Tf R complexes cluster into clathrin-coated pits to be delivered to early endosomes. The pH of endosomes is lowered by an ATP-dependent proton pump; under these conditions, the release of iron from Tf is facilitated through its interactions with Tf receptor (8). Unlike many other ligands, apoTf (devoid of its cargo iron) remains bound to its receptor and is therefore recycled back to the cell surface, where it can be released for further rounds of iron delivery (9–11). The vesicular movement of the Tf receptor through the early sorting and recycling endosomal pathway is well-defined (12).

In screening the small molecule inhibitors of exocytosis for their effects on cellular iron assimilation through the Tf cycle, we fortuitously identified a family of sulfonamide compounds that blocked uptake of iron via the Tf receptor pathway. Seven members of this family were characterized with IC50 values ranging from 0.1 µm to greater than 250 µm. Detailed study of one member, 16D10, revealed that treatment with this compound increases the pH of compartments of the endocytic pathway, thereby blocking both the release of iron from Tf and recycling of Tf receptors to the cell surface. Results from biochemical experiments presented here demonstrate that a potential target of the compounds is the V1 domain of vacuolar ATPases (V-ATPases), which is responsible for pumping protons into the lumen of a variety of organelles, including endosomes, lysosomes and the Golgi apparatus. In addition, we found that members of the sulfonamide family can act as proton ionophores in vitro. While it is well-established that maintenance of organellar pH is a critical factor in both endocytic and exocytic membrane traffic, the precise role of acidification in these pathways remains largely unknown. The novel class of sulfonamide inhibitors therefore provides new chemical tools to better understand the function of organelle pH in membrane traffic and to study functional aspects of V-ATPases in particular.

Results

Compounds that block Golgi to plasma membrane traffic inhibit Tf-mediated iron uptake

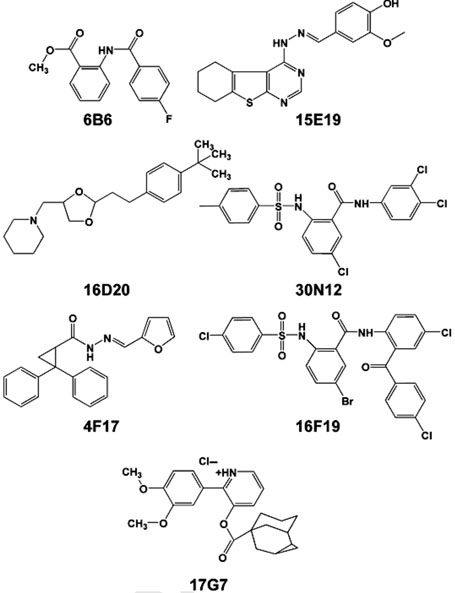

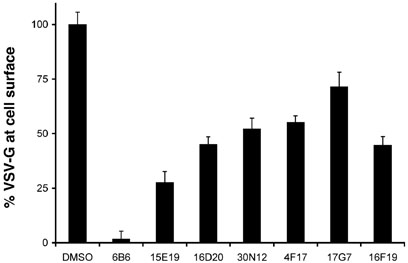

In a recent high throughput screen of more than 10 000 chemicals from the DIVERSet E (Chembridge Corp., San Diego, CA) for inhibitors of exocytosis, seven small molecules were identified that reduced the delivery of GFP-tagged VSV-Gts045 to the cell surface (4,5). Two compounds, 6B6 and 15E19, now called Exo1 and Exo2, respectively, were characterized to block exit from the ER (4). Five others, 16D20, 30N12, 4F17, 17G7, and 16F19, did not affect VSV-Gts045 traffic from the ER to the Golgi apparatus, but instead inhibited the membrane protein's exit from the Golgi to the cell surface (5). Structures of these seven small molecule inhibitors are shown in Figure 1. When tested at 50µm, these compounds reduced the amount of the viral glycoprotein delivered to the cell surface with inhibitory potencies that ranged between 95 and 30%, with 6B6> 15E19> 16D20-16F19-30N12-4F17> 17G7 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Chemical genetic screening identifies compounds that reduce exocytosis of GFP-tagged VSV-Gts045 to the cell surface. Structures of seven small mol-ecule compounds were identified in a screen of > 10000 chemicals from the Chembridge DIVERSet E library to block secretion of VSV G. Screening conducted by Y.F. (4,5).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of VSV-Gts045 exocytosis. To examine the effects of chemicals shown in Figure 1, BSC1 cells were transduced with adenovirus to express GFP-tagged VSV Gts045 and grown overnight at 40 °C. Prior to transfer to 32 °C, 50 µm of each compound was added to the media for 1 h. After 3 h incubation at 32 °C, the amount of VSV Gts045 at the cell surface was measured by incubating with monoclonal VSV-G antisera as detailed in the Materials and Methods section. As a control for nonspecific binding, cells were also treated with 10µm brefeldin A, a drug known to completely block transport to the cell surface. After subtraction of background (measured in the presence of brefeldin A), data were normalized to the total fluorescence signal detected by GFP expression. Shown is the percentage of surface VSV-G relative to the total GFP signal (n=9; ±SEM). Experiments performed by Y.F.

To examine the effect of this set of inhibitors on the endocytic pathway, uptake of radioactive iron from Tf was measured in the presence of 50µm of the compounds. After association with its receptor at the cell surface, Tf delivers iron to cells via the endocytic pathway. As shown in Figure 3, none of the drugs affected cell-associated 55Fe at 4°C (open bars), a temperature that blocks endocytosis of Tf. These data indicate that none of the drugs permeabilizes cells or in any way promotes none-ndocytic uptake of iron from Tf. However, Tf-mediated uptake of 55Fe at 37 °C (closed bars) was inhibited by 85% to 5% with an order of potency 16D20-30N12-16F19» 17G7>4F17-15E19-6B6. This order of potency was completely different from inhibition of VSV-G traffic and confirms the selectivity of 6B6 (Exo1) and 15E19 (Exo2) to inhibit ER-to-Golgi transport. In contrast, inspection of the chemical features of two of the most potent inhibitors of both exocytic and endocytic traffic, 30N12 and 16F19 (Figure 1), suggested a common structural basis for their effects on both pathways. Based on the presumption that these compounds might selectively target a cellular component functioning in both the endocytic and exocytic pathways, these compounds became a focus for further investigation.

Figure 3.

Inhibitors of the exocytic pathway block(55)Fe uptake from Tf. HeLa cells were treated with 50 µm of inhibitors shown in Figure 1 for 4h at 37 °C (solid bars) or 4 °C (open bars) in the continued presence of 40nm 55FeTf. After washing, cells were lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 containing 0.1% NaOH and cell-associated 55Fe was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Results were normalized to protein concentrations to determine pmol 55Fe/mg cell protein. The means of duplicate determinations are shown from a single experiment with similar results obtained on several occasions. Experiments were performed by J.X.B and P.D.B.

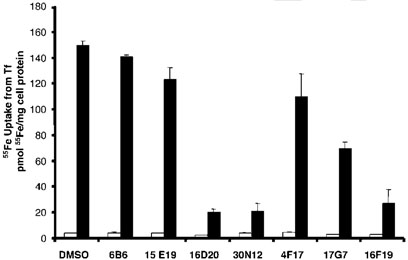

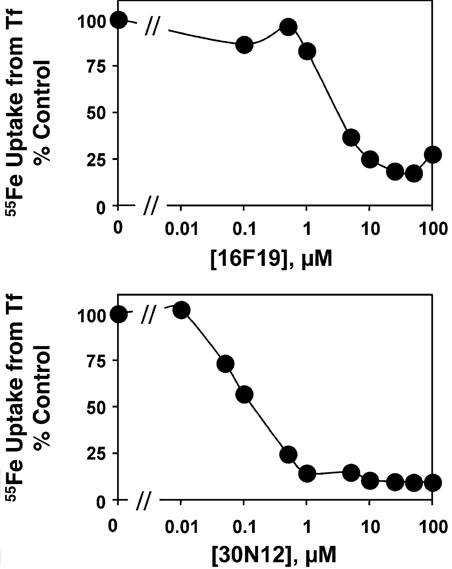

Inhibition of Tf-mediated iron uptake by 30N12 and 16F19 is dose-dependent and reversible

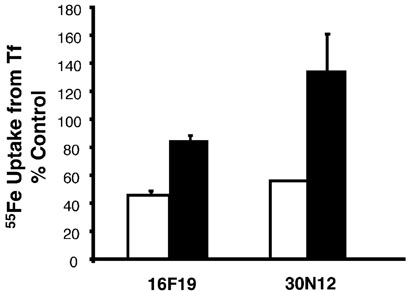

The dose–response of inhibition of Tf-mediated iron uptake by 30N12 and 16F19 was determined. Both compounds effectively blocked iron uptake in a dose-dependent manner, with IC50 values of 0.1 and 2 µm, respectively (Figure 4). Moreover, inhibition by 30N12 and 16F19 was reversible (Figure 5). In these experiments, cells were either first treated with vehicle solvent (DMSO) followed by a 1-h incubation with the inhibitor (open bars) or they were treated with the compounds for 1 h, followed by a 4-h recovery period with DMSO added (solid bars). Reversal of the inhibition of Tf-mediated iron uptake under the latter conditions also confirmed that there were no confounding solvent effects of vehicle treatment, and that these compounds were not toxic to cells.

Figure 4.

Dose-response to 16F19 and 30N12. Inhibition of 55Fe uptake from Tf was determined exactly as described for Figure 1. HeLa cells were incubated with the concentrations of inhibitors and the amount of 55Fe taken up by the cells was normalized to control cells which were treated with vehicle (DMSO) alone. Experiments performed by J.X.B and P.D.B.

Figure 5.

16F19 and 30N12 inhibit 55Fe uptake from Tf in a reversible manner. HeLa cells were either first incubated with 2 µm 16F19 or 0.5 µm 30N12 for 1 h followed by a 4-h recovery incubation with 0.5% DMSO after removal of the drug, or cells were first incubated for 4 h with 0.5% DMSO followed by a 1 h incubation with sulfonamides. Cells treated under both conditions were then incubated with 40 nm 55Fe-Tf for 1h. During the 1-h assay, cells continued to be incubated either with DMSO (closed bars) to test reversibility (closed bars) or with sulfonamide to directly inhibitory potency in assay (open bars). 55Fe uptake was normalized to protein content and expressed as percentage control (cells incubated with 0.5% DMSO in the absence of sulfonamide). Experiments performed by P.D.B.

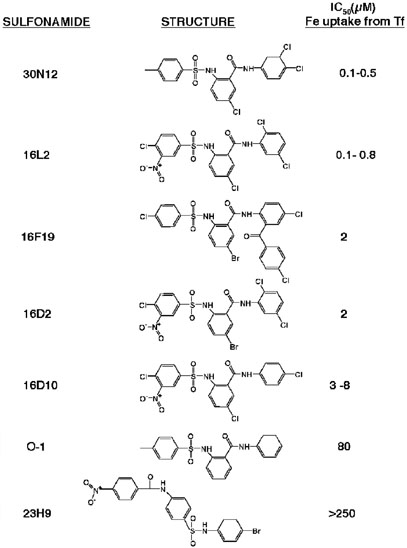

Structurally related sulfonamides inhibit membrane traffic

Based on the chemical structures of 30N12 and 16F19, five other sulfonamide compounds were selected from the Chembridge DIVERSet E (Figure 6). The ability of members of this family of sulfonamides to inhibit uptake of 55Fe from Tf was determined in a series of dose–response experiments that established IC50 values from 0.1 µm (30N12) to > 250 µm (23H9). Inhibition studies of the ability of these sulfonamide family members to block cell surface delivery of VSV G protein revealed a similar range of IC50 values (data not shown). From the relative potency of the compounds (30N12> 16L2-16F19–16D2> 16D10»O-1 and 23H9), limited structure-activity information can be deduced. In more potent compounds, the sulfonamide is flanked by a single benzyl ring on the sulfo-group, whereas bulkier aryl groups are tolerated on the amide (e.g. 16F19). A converse configuration (23H9 vs. 16L2) significantly impairs inhibitory potency. Chloro- and/or nitroso substitu-ents on the single benzyl ring off the sulfo-group do not appear to affect the compound's action (e.g. 30N12 vs. 16L2). On the aryl group immediately next to the amide, a halide is invariantly present in the para position; elimination of this halide greatly reduces the ability of the sulfonamide to inhibit both endocytosis and exocytosis (O-1). For more detailed functional studies, we focused on 16D10 since it has a structure representing the most significant aspects of this class of compounds: both chloro- and nitrosogroups are present on an aryl ring adjacent to the sulfo-group and a halide is para to the amide on a benzyl group, which itself is connected via an amide linkage to a second benzyl ring. As a control for some of these experiments, we employed O-1, which lacks the halide and nitroso constituents and displays an IC50 value for inhibition of 55Fe uptake that is one order of magnitude greater than 16D10.

Figure 6.

Family of sulfonamide inhibitors of membrane traffic. Based on the structures of 30N12 and 16D19, several additional compounds were screened for their ability to inhibit membrane traffic. Dose–response curves for inhibition of 55Fe uptake from Tf were measured as described for Figure 4. In addition to 30N12 and 16F19 (5), structures of 16L2, 16D2, 16D10, 23H9 and O-1 are shown along with the relative IC50 values determined for inhibition of Tf-mediated iron uptake. IC50 values were determined as described in Materials and Methods using GraphPad PRISM3 software. Experiments performed by J.X.B and P.D.B. with data analysis by T.J.F.N.

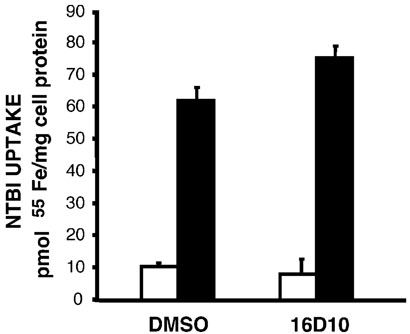

16D10 does not inhibit non-Tf bound iron (NTBI) uptake or ER-to-Golgi traffic

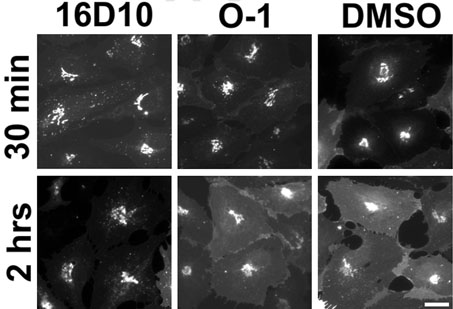

To test whether the inhibition of iron assimilation was linked to the Tf-Tf receptor (TfR)-dependent pathway, the effect of 16D10 on NTBI uptake was examined. NTBI uptake involves transport of the metal directly across the cell surface in the absence of Tf, and does not depend on endocytosis (13). As shown in Figure 7, NTBI uptake was unaffected by the presence of 50 µm 16D10. From these data, we conclude that 16D10does not act as a membrane perturbant or iron chelator to disrupt Tf-mediated delivery and cellular iron assimilation from this pathway. These results also indicate that inhibition of Tf-mediated iron uptake by the sulfonamide is unlikely to be caused by cellular ATP depletion, since NTBI uptake is an energy-requiring process (14). To further examine the selectivity of 16D10, we took advantage of GFP-tagged VSV-Gts045 to follow its movement by fluorescence microscopy. This temperature-sensitive mutant accumulates in the ER until cells are placed at permissive temperature (32 °C). Under these conditions, most of the GFP-tagged protein is observed in the Golgi apparatus after a 30-min incubation (upper panels, Figure 8). Treatment of cells with inactive O-1 or active 16D10 did not alter transport of the VSV G protein to this compartment. Longer incubation times (2 h) resulted in the appearance of fluorescence at the cell surface; however, the presence of 16D10 significantly reduced traffic of the GFP-tagged protein to the plasma membrane (lower left panel, Figure 8). The observation that 16D10 does not block ER-to-Golgi transport is consistent with previous results obtained for 30N12 and 16F19 (5) and bolsters the idea that the sulfonamides selectively inhibit specific steps of membrane traffic involved in transport to the cell surface.

Figure 7.

16D10 sulfonamide does not inhibit NTBI uptake. The uptake of 55Fe was measured in the absence of Tf by using a chemical chelate with NTA (1: 4 ratio) to present the cation to HeLa cells. To measure nontransferrin bound iron (NTBI) uptake, cells were preincubated with 50µm of the indicated compounds for 30 min prior to addition of 2µm 55FeNTA. After 1 h incubation at either 4 °C (open bars) or 37 °C (closed bars), uptake was quenched by placing the cells on ice and incubating with unlabeled 1 mm FeNTA to displace surface-bound iron; lysates were collected to measure cell-associated radioactivity and protein to calculate pmol 55Fe/mg cell protein. Shown are the means of duplicate determinations from a single experiment with similar results obtained on several occasions. Experiments performed by J.X.B and P.D.B.

Figure 8.

Sulfonamides block VSV-Gts045 transport from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. Cells were transduced to express VSV-Gts045 and incubated as described for Figure 2 except that 100µm of 16D10 or O-1 were added before transfer to 32 °C. After 30-min and 2-h incubation periods, the cells were fixed with 3% formaldehyde and images of GFP-tagged VSV-Gts045 were collected using a 40× lens. Scale bar = 10µm. Experiments performed by Y.F.

16D10 reduces Tf endocytosis due to receptor down-regulation

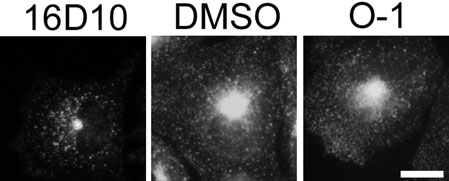

Endocytic uptake of Tf is initiated at the cell surface upon receptor binding, with internalization by clathrin-coated vesicles followed by delivery of the ligand to early or sorting endosomes. Control experiments confirmed that the sulfonamides did not interfere with Tf binding to its receptor (data not shown). To test whether subsequent steps of Tf endocytosis were affected, internalization of alexa594-labeled Tf was followed by fluorescence microscopy. The results in Figure 9 demonstrate that endocytic uptake of Tf continued in the presence of 10µm 16D10 (left panel). Notably, there was no change in the morphology or distribution of endocytic compartments containing the fluorescent probe in cells treated with the compound. However, a significant decrease in the amount of ligand internalized was observed relative to control cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) or the inactive sulfonamide O-1. Thus, the pattern of alexa594-Tf traffic through the endocytic pathway is normal but the amount of ligand internalized is dramatically reduced by 16D10.

Figure 9.

16D10 sulfonamide reduces entry of Tf into cells. TRVb-1 cells were pretreated with 10µm 16D10, O-1 or DMSO for 30 min and then 40µg/mL Alexis594-labeled Tf was added for an additional 30 min. Cells were fixed with 3% formaldehyde and fluorescence images were collected using the same exposure times with a 63× oil immersion lens. Scale bar = 5 µm. Experiments performed by T.J.F.N.

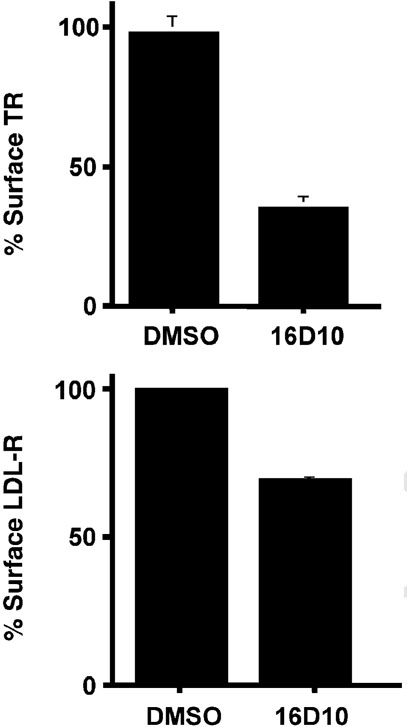

To evaluate whether reduced uptake is the result of a reduction in the number of Tf receptors on the plasma membrane, 125I-Tf binding studies were performed (Figure 10, upper panel). Treatment with 10µm 16D10 for 30min induced a loss of >60% surface binding sites. Moreover, the number of surface low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors was also reduced in cells treated with 16D10 (Figure 10, lower panel), indicating that the observed effects were not unique to the Tf receptor. Control experiments also confirmed that the latter observations did not result from altered LDL binding in the presence of 16D10 (data not shown). From these combined results, we infer that the sulfonamide perturbs the endocytic recycling pathway to induce receptor down-regulation.

Figure 10.

16D10 sulfonamide promotes down-regulation of cell surface receptors. Top panel: TRVb-1 cells were preincubated in serum free media for 90min at 37 °C, then treated with or without 10µm 16D10 for 30min at 37 °C. After cells were chilled on ice, surface 125I-Tf binding was measured as described under Materials and Methods. Data shown are the average (± SD) of two experiments. The data are plotted as a fraction of the 125I-Tf bound to the surface of control cells. Bottom panel: TVRb-1 cells were grown for 3 days in medium supplemented with lipoprotein deficient serum to up-regulate endogenous LDL receptor. On the day of assay, cells were washed twice in serum-free medium and pretreated with 10µm 16D10 or DMSO alone for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were then chilled on ice, and LDL labeled with 125I on the lipoprotein moiety was added for 1 h on ice at a final concentration of 25µg/mL. Non-bound LDL was washed away with phosphate-buffered saline and cells were lysed in 0.1N NaOH for 30 min at room temperature. For each sample, an aliquot was counted by LSC and assayed for protein levels. Data are expressed as LDL receptor levels as a percentage of control. Note that saturating levels of ligands were used to measure cell surface binding for Tf and LDL receptors, 3µg/mL and 25µg/mL, respectively. Experiments performed by T.J.F.N and T.D.C.

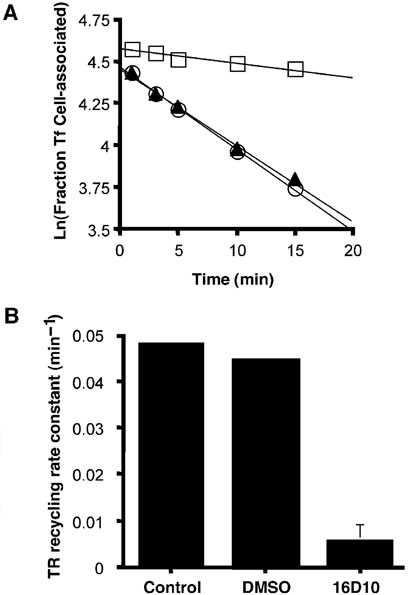

16D10 impairs Tf receptor recycling

A reduction in the amount of receptors on the cell surface can result from an accelerated rate of endocytosis, a reduced rate of exocytic return to the cell surface, or a combination of both perturbations. Experiments measuring the endocytic rate constant by the In/Sur method (15) indicated that Tf receptor internalization was not up-regulated by 16D10, as would be the case if the reduction in receptors on the cell surface was a consequence of altered internalization. However, recycling of Tf receptors back to the cell surface was significantly impaired in the presence of this compound. In these experiments, the release of internalized 125I-Tf was monitored in the presence of 100µm desferrioxamine (an iron chelator) and 3µg/mL unlabeled Tf to prevent ‘treadmilling’ or recapture of 125I-Tf back into the cells. The rate of 125I-Tf release was greatly reduced in the presence of 16D10 (Figure 11, panel A) and from a series of experiments (n = 4), a near 10-fold reduction in the recycling rate constant was determined (Figure 11, panel B).

Figure 11.

16D10 sulfonamide impairs Tf receptor recycling. Panel A: TRVb-1 cells (treated with or without 16D10) were incubated with 125I-Tf for 2h at 37 °C to allow ligand internalization, then washed and incubated for the indicated time to allow recycling and release of Tf. The amount of 125I-Tf remaining as a function of time is shown for control (open circles), cells treated with 0.5% DMSO (closed triangles) and cells treated with 10µm 16D10 (open squares). Panel B: Recycling rate constant (min −1) was determined from the slope of lines shown in the middle panel; shown is the mean value (±SD) determined in four separate experiments. Experiments performed by T.D.C.

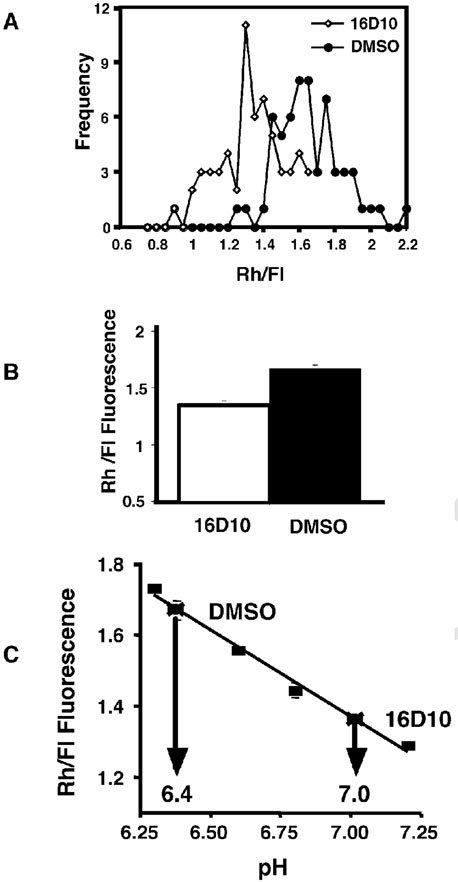

Sulfonamides alter endosomal and lysosomal pH

Previous studies have shown that flux of receptors and membrane components through the recycling pathway is slowed when the endosomal pH is raised (11,16–18). In addition, an intracellular retention or accumulation of recycling receptors is observed, an effect similar to the down-regulation of surface Tf and LDL receptors induced by 16D10 (Figure 10). We therefore tested whether the sulfonamides alkalinized Tf-containing compartments using a fluorescence ratio imaging method to determine the pH of recycling endosomes with doubly labeled Rh/Fl-Tf (17). 16D10 promoted an increase in Fl fluorescence, consistent with a rise in endosomal pH (Figure 12, panels A and B). Using methylamine to equilibrate cells with buffers of known pH, a standard in-cell calibration curve was constructed (Figure 12, panel C). From the values of Rh/Fl ratios in control vs. 16D10-treated cells, it was determined that the pH of recycling endosomes was raised from 6.4 to 7.0 in the presence of the sulfonamide. These results are consistent with the model that receptor down-regulation and impaired Tf receptor recycling are induced by elevation of endosomal pH by the sulfonamide. Elevation of endo-somal pH would also significantly impact the release of iron from Tf, since dissociation of the metal requires acidic conditions (8,10,11,16).

Figure 12.

16D10 sulfonamide alters endosomal pH. Panel A: Histogram of the distribution of Rh/Fl ratio of peri-centriolar recycling compartments of control and 16D10 treated cells. Compound 16D10 causes an increase in the Fl fluorescence, resulting in a shift of the distribution to the left. The data are from a representative experiment and 60 peri-centriolar recycling compartments from each condition were measured. Panel B: The average ± SEM Rh/Fl ratio of peri-centriolar recycling compartment from control and 16D10 treated cells (n = 60). Panel C: Estimation of endosomal pH based on the Rh/Fl ratio. A standard pH curve was constructed by determining the Rh/Fl ratio in cells whose endosomes were equilibrated to a known pH (squares). The Rh/Fl ratio measured in control and 16D10 cells can be converted to pH using this standard curve. The peri-centriolar endosomes in controls cells have a pH of ~6.4 and those in cells treated with compound 16D10 have a pH of ~7.0. Experiments performed by T.D.C.

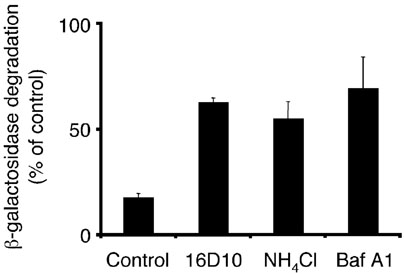

To study whether the sulfonamides could also alter lyso-somal pH, the degradation of a fluid phase endocytic marker was followed. K562 cells were allowed to internalize exogenously added avidin-β-galactosidase at 20 °C to load the early endosomal compartment as previously described; a subsequent shift of temperature to 37 °C results in trafficking of this marker enzyme to the lyso-somes where it is degraded (19). The amount of b-galac-tosidase remaining after the chase period can be measured in cell lysates by enzymatic hydrolysis of the fluorescent substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactoside. Agents that are known to raise the lysosomal pH, such as NH4Cl and the V-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1, prevent the degradation of β-galactosidase (Figure 13). Similar to these lysosomotropic agents, addition of 10µm 16D10 also inhibits the loss of β-galactosidase activity, consistent with the idea that the sulfonamides elevate the pH of the lysosomes.

Figure 13.

16D10 and 16D2 prevent lysosomal degradation. K562 cells were incubated with β-galactosidase at 20 °C for 60 min to allow its internalization by fluid phase into endosomal (prelysosomal) compartments. After washing, cells were incubated for 30min in the presence of 10µm 16D10 or 1% DMSO vehicle control, 0.5µm bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) or 20 mm NH4Cl. The intracellular activity of internalized β-galactosidase following the chase period reflects access to lysosomes as is manifested by decreased β-galactosidase activity due to its proteolytic degradation within lysosomes. Results of duplicate samples were normalized to the total amount of activity before the chase period and are expressed as percentage control (DMSO vehicle treatment). Experiment performed by T.J.F.N.

Sulfonamides inhibit V-ATPase activity and act as potent proton ionophores

V-ATPases are required for the maintenance of the pH of different organelles, including the endosomal, lysosomal and Golgi compartments (20). Because 16D10 appeared to raise the pH of compartments in the endocytic pathway, the V-ATPase is an attractive candidate target for inhibition by the sulfonamides. To better understand the mechanism of action of these inhibitors, the effects of 16D2, 16D10 and O-1 on V-ATPase activity were studied biochemically (Table 1). The active sulfonamides, 16D2and 16D10, inhibited hydrolysis of ATP by V1-ATPase with IC50 values of 6 and 15µm, respectively. These values correspond fairly well with their respective potencies for inhibition of iron uptake in vivo (Figure 6). Also consistent with the efficacy of sulfonamide inhibition in vivo, the relatively inactive compound O-1 inhibited only 30% of ATPase activity at a concentration of 250 µm. The IC50 values for inhibition of ATP hydrolysis were shifted by an order of magnitude, however, when the intact V1V0-ATPase was employed in these assays. This observation suggests that the assembly of the V1 sector onto the V0 domain may somehow partially protect the enzyme from sulfonamide inhibition, raising the possibility that the binding site for the sulfonamides may be in the stalk region at the V1V0 interface.

Table 1.

Inhibition of ATPase activity of the catalytic sector V1 and the intact V-ATPase by sulfonamide compounds. The ATP hydrolysis activity of the dissociated catalytic sector V1 of bovine brain V-ATPase or the intact enzyme was measured in the presence of either MgCl2 or CaCl2, respectively. The IC50 of sulfonamides on the V-ATPase activity was obtained by titration of each compound. At the concentration of 250 µm, the highest concentration we have tested, the compound O-1 inhibited less than 50% of either ATPase activity. Experiments performed by J.W.

| Compounds | IC50 (µM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| V1 ATPase | Intact V-ATPase | |

| 16D2 | 6 | 27 |

| 16D10 | 15 | 32 |

| O-1 | > 250 | > 250 |

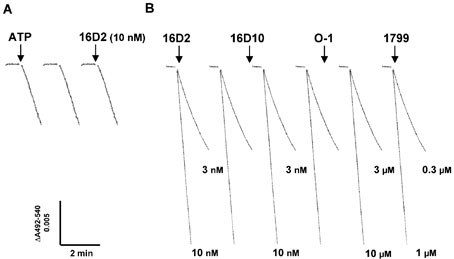

The effects of the sulfonamides on the ATP hydrolysis activity of the V-ATPase were unusual since most specific inhibitors, such as bafilomycin A1, concanamycin A, and salicylihalamide A, do not inhibit ATP hydrolysis activity of dissociated V1 or uncoupled V1V0 complex but instead inhibit ATP hydrolysis of V-ATPase by blocking the proton channel (21). To directly investigate the effects of the sulfonamides on the proton transport function of V-ATPase, in vitro assays were performed using proteolipo-somes as previously described (21). During these studies, 16D2 was found to collapse the proton gradient generated by ATP-driven proton transport by the V-ATPase at a very low concentration (10µm) as shown in Figure 14A. Further investigation using a protein-free liposome system to measure membrane potential-driven proton conductance revealed that the two effective sulfonamide compounds tested (16D2 and 16D10) act as proton ionophores in the nm range, whereas O-1 is more than a 1000-fold less potent (Figure 14B). This activity was unexpected and the potency of the sulfonamides' effects was quite surprising since most commonly employed proton ionophores are effective at ~ 1 µm. For example, the activity of the proton ionophore 1799 (bis-(hexafluoroacetonyl)acetone) at 1 µm is shown in Figure 14B. Because much higher concentrations of the sulfonamides are required to block intracellular membrane trafficking in vivo, exactly how these in vitro ionophore effects correlate with the influence of the compounds on cellular activities remains uncertain. Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine their precise influence on the V-ATPase proton pump function in vitro due to the confounding proton ionophore effects.

Figure 14.

Proton ionophore activity of sulfonamides. Panel A: Bovine brain V-ATPase was reconstituted into proteoliposomes and assayed for ATP-driven proton transport activity. Sulfonamide analog 16D2 (10 nm) added at the end of the assay was found to collapse the proton gradient. Panel B: The proton ionophore activity of sulfonamides was measured as membrane potential-driven proton conductance in a protein-free liposome system. Sulfonamides and 1799 were added at the indicated concentrations. Experiments performed by J.W.

Discussion

Chemical genetics holds the promise of providing small molecules to study biological processes in greater detail. For example, recent screening efforts resulted in the discovery of two new inhibitors (Exo1 and Exo2) of ER-to-Golgi traffic (4,5). The effects of Exo1 appear similar to brefeldin A, a well-known fungal inhibitor of Golgi traffic (22). Unlike brefeldin A, however, its actions do not involve adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribosylation of Bars50 or inhibition of guanine nucleotide exchange activity of Golgi-associated ADP-ribosylation factors (ARFs) (4). Thus, Exo1 is a new chemical tool to help further dissect the mechanistic elements involved in ER-to-Golgi traffic. In the present study, we examined these and five additional compounds for potential effects on the endocytic pathway. From this analysis, two structurally related compounds, 30N12 and 16F19, were discovered to block Tf-mediated iron delivery through the endocytic pathway. Both compounds were previously shown to interfere with Golgi-to-plasma membrane but not with ER-to-Golgi traffic (5), suggesting possible influences on membrane trafficking to the cell surface. 30N12 and 16F19 therefore became the founding members of a larger class of sulfonamide derivatives characterized in this investigation.

Members of the sulfonamide family inhibit endocytic uptake of iron via Tf-TfR complexes and the transport of VSVG protein from the Golgi to the plasma membrane in a dose-dependent and reversible manner. Structural relationships of this family include aryl groups linked across the sulfonamide, with a benzyl halide para- to the amide. While our structure–activity profiling was limited to a small set of seven compounds, searches of the Chembridge DIVERSet E indicate that approximately 30 family members are available for study in this chemical library. Among the sulfonamides we have studied, IC50 values for inhibition of Tf-mediated iron uptake ranged from 0.1 µm to >250µm. Similar values for inhibition of Golgi-to-plasma membrane traffic were observed, while none of the compounds appeared to block ER-to-Golgi transport.

The functional effects of one sulfonamide, 16D10, were studied in greater detail. The structure of 16D10 represents the most significant chemical attributes of the sulfonamide family. 16D10 inhibited Tf-mediated iron uptake with an IC50 ~€3–8µm but did not affect NTBI uptake. In cells treated with 16D10, endosomal pH was elevated from 6.4 to 7.0. Since release of iron from Tf requires endosomal acidification (8,10,11,16), dissociation of the metal would be blocked in the presence of this sulfonamide. Therefore, this effect accounts for the observed inhibition of Tf-mediated iron uptake and provides an explanation for why NTBI uptake is not affected by the compound. The alkalinization of endocytic compartments by 16D10 was also associated with a reduction in the number of surface Tf receptors due to impaired receptor recycling. This effect was not specific to the Tf receptor since down-regulation of the LDL receptor, another constitutively recycling receptor, was also observed. Previous studies of recycling endocytic traffic in the presence of pH-disrupting lysosomotropic agents have shown that Tf uptake is disrupted by alkalinization of intracellular organelles (7,9,23). Alterations in membrane traffic induced by weak bases like NH4Cl, chloroquine or primaquine, include changes in the distribution of other recycling receptors as well. For example, monensin inhibits dissociation of ligand from the asia-loglycoprotein receptor (24,25) such that lysosomal degradation is blocked (26). Weak bases also induce a loss of cell surface asialoglycoprotein receptors, with concomitant increases in intracellular pools (24–28). Similar to our observations that 16D10 promotes down-regulation of the LDL receptor, monensin also has been reported to block recycling of this receptor (29). The observation that 16D2 and 16D10 block the loss of endocytosed β-galactosidase activity due to membrane traffic is consistent with the idea that, very much like these other lysosomotropic agents, the influence on lumenal pH by these compounds is not specific to endosomes, since lysosomal protease activity also appears to be inhibited in cells treated with the compounds.

Recent pharmacologic advances have provided specific inhibitors of the vacuolar H+-ATPase to study the role of organelle pH in membrane traffic. Macrolide antibiotics bafilomycin A1 and concanamycins A and B have been identified to disrupt V-ATPase activity (30,31), although their precise mechanism of action is not yet entirely clear (20). A class of benzolactone enamides has also been identified to potently and selectively inhibit mammalian V-ATPase, but they are even less well-characterized (32). Of these V-ATPase inhibitors, bafilomycin A1 has been used most extensively in studies of membrane trafficking. Bafilomycin A1 inhibits the ATPase activity of the intact V-ATPase by blocking its proton channel (33) and subsequently raises the pH of both endosomal (17,18,34), and Golgi (35,36) compartments. Treatment with bafilomycin A1 markedly reduces the rate of TfR recycling and promotes receptor down-regulation (17,18,37,38). Similar to bafilomycin A1, 16D10 also raises endosomal pH to inhibit Tf-mediated iron uptake, induces receptor down-regulation, and impairs receptor recycling. It thus follows that the V-ATPase is a strong candidate target for inhibition by this compound. This model is also consistent with the fact that the sulfonamides do not block ER-to-Golgi transport but do inhibit Golgi-to-plasma membrane traffic of VSV-G protein (5). A pH gradient exists across the secretory pathway such that the trans-Golgi and the trans-Golgi network (TGN) are acidified (20). Similar to our observations of sulfonamide family members, bafilomycin A1 does not affect exit of VSV-G protein from the ER, but does cause its accumulation in the Golgi of virally infected cells (39). Prodigiosin-25, which uncouples V-ATPase driven proton transport, also inhibits cell surface transport of VSV-G (40).

Biochemical studies of isolated V-ATPase support the model that the sulfonamides may act by affecting its function. However, although the sulfonamides were found to inhibit hydrolysis of ATP by the V-ATPase in vitro, one surprise was that the sulfonamides also collapsed the proton gradient generated by ATP-driven proton transport of V-ATPase reconstituted in proteoliposomes. Studies using protein-free liposomes subsequently confirmed that the sulfonamides can act as proton ionophores. In fact, the proton ionophore activity of the compounds 16D2 and 16D10 in vitro is at least 100-fold higher than other ionophores commonly used in biochemical studies (e.g. 1799, FCCP, etc.). By comparing in vitro and in vivo data on the effects of the sulfonamides, however, it becomes apparent that the proton ionophore activity of these compounds must be ‘neutralized’ by cellular mechanism(s) in vivo. It seems likely that the 1000-fold concentration difference observed to elicit effects in vivo vs. in vitro reflects catab-olism of the compounds in some manner that may eliminate or significantly impair their ionophore activity. At this time, it remains uncertain whether these compounds act to raise the pH of intracellular compartments directly as proton ionophores or indirectly through inhibition of V-ATPase function. They could potentially act through both mechanisms, and it is also possible that their effectiveness as proton ionophores differs in different organelles such that this activity may be more responsible for some cellular effects than others. With respect to the inhibition of iron uptake which is thought to occur in endosomes, we note that the relative potencies of 16D2 and 16D10 for inhibition of ATP hydrolysis by V1-ATPase in vitro are compatible with the relative IC50 values measured in vivo, while their proton ionophore activities at 1000-fold greater concentrations are almost identical in vitro. Thus, the model that the compounds inhibit ATP hydrolysis and thereby disrupt V-ATPase function is more compatible with the sum of our data for inhibition of Tf-mediated iron import.

Although we favor the view that the sulfonamides block V-ATPase function, it is curious that the IC50 values measured for inhibition of ATP hydrolysis by the intact V1–V0 complex are significantly higher than for the isolated V1 sector alone. One possible explanation for these results arises from the inference that the compounds have a higher affinity to V1 relative to the intact V-ATPase. The equilibrium between intact V-ATPase and its dissociated V1 and V0 domains in response to energy utilization and other cellular events has been well-established in yeast and insect systems (41,42), and is likely to be true in mammalian cells as well. In light of our data, the sulfonamides may inhibit the V-ATPase primarily by binding to free V1, which could result from the disassembled inactive enzyme or which might even prevent V1 from assembly with V0. Although it can not be ruled out that the sulfonamides bind to the catalytic center of the transporter, wherein the pump's conformation changes when assembled with V0, it is more likely that the binding site for these compounds is within the stalk region at the V1–V0 interface. In this regard, the sulfonamide compounds provide a particularly attractive tool to further study the structure, function, and regulation of V-ATPases.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

BSC1 fibroblasts were cultured and transduced to express VSV Gts045 as previously described (4). ForTf uptake measurements, HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and grown to ~ 60% confluency in 6-well plates prior to iron uptake studies. The CHO cell line, TRVb-1, was grown in 24-well plates with McCoy's medium containing 5% FBS to measure recycling and endosomal pH as described below. This cell line expresses the human Tf receptor but not the endogenous hamster Tf receptor, and has been extensively used for analysis of Tf receptor endocytic traffic (43). For 125I-Tf surface binding and alexa-Tf uptake experiments, TVRb-1 cells were maintained in Ham's F12 medium with 10% FBS.

Small molecule inhibitors

Compounds were purchased from Chembridge Corp. and dissolved in DMSO to a final concentration of 10mm and stored at − 80 °C until use. During the course of this investigation, we discovered that the potency of the compounds was greatly reduced if serum or bovine serum albumin was present in the assay medium, presumably because albumin may act as a scavenger to bind the lipo-philic compounds, thus reducing their bioavailability.

VSV-Gts045 exocytosis

BSC1 cells transduced with adenovirus to express GFP-tagged VSV Gts045 were grown overnight at 40 °C in 96-well clear-bottom plates at a cell density of 10 000/well. Prior to transfer to 32 °C, compounds were added to the media at a final concentration of 50µm and cells were incubated for 1 h at 40 °C. As a control, cells were also treated with 10µm brefeldin A to completely block transport to the cell surface. After 3 h incubation at 32 °C, cells were fixed with 3% formaldehyde and stained with the monoclonal antibody 8G5 to detect GFP-tagged VSV-Gts045-GFP at the cell surface using secondary goat antimouse labeled with alexa594. Cell-associated fluorescence was measured using an automated fluorescence microscope (Universal Imaging Corp., Downington, PA) with triple band-pass filters (excitation wavelengths of 360/490/570 nm; emission wavelengths of 460/530/625 nm). After subtraction of nonspecific binding of secondary antisera (measured in the presence of brefeldin A), the percentage of surface VSV-Gts045 was calculated relative to the total amount of cell-associated GFP fluorescence. This surface/total ratio represents the extent in transport of GFP-tagged VSV-Gts045 to the cell surface.

Tf-mediated iron uptake

Human apoTf (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was loaded with 55Fe as previously described (13). HeLa cells were washed with serum-free media and incubated with 40 nm 55Fe-Tf at 37 °C with or without inhibitors at the concentrations shown in the Figure legends. As a control, cells were incubated with vehicle alone (0.5% DMSO). At the end of the uptake period, cells were rapidly chilled on ice, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times, then incubated with 40µg/mL unlabeled Tf to displace surface-bound 55Fe-Tf for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were lysed with 0.1 % Triton X-100 containing 0.1 % NaOH. Cell-associated radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting and cell protein was measured using the Bradford assay (44) to calculate pmol 55Fe/mg cell protein.

Non-Tf-bound iron uptake

Iron uptake in the absence of Tf was measured using a chelate of 55Fe with nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) at a 1 : 4 ratio (13). HeLa cells were preincubated at 37 °C in serum-free media with 50µm inhibitor for 30min, then 2µm 55Fe-NTA was added for 1 h. At the end of the uptake assay, cells were chilled on ice, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline, then incubated with 1 mm unlabelled Fe-NTA on ice to displace any surface-bound iron. Lysates were prepared and pmol 55Fe/mg cell protein was determined as described above.

Alexa594-Tf uptake

TRVb-1 cells were first incubated at 37 °C for 2 h in serum-free Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) to remove any residual Tf bound to receptors. After preincubation with 10µm 16D10 or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) in the same medium for 30min at 37 °C, cells were incubated in the presence of 16D10 or DMSO for an additional 30min with 40µg/mL alexa594-Tf added to the media. After internalization of the fluorescent ligand, cells were washed in PBS containing 2 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2, fixed for 30min on ice with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were analyzed for Tf uptake by fluorescence microscopy using a 63X oil immersion lens.

Down-regulation of cell surface Tf receptors

The effects of inhibitors on cell surface Tf receptors on the surface were determined by first incubating TRVb-1 cells in serum-free medium for 2h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Compounds or DMSO were added during the final 30min of this incubation. The cells were transferred to ice for 10 min to inhibit membrane trafficking, washed, and incubated in HEPES-buffered pH 7.2 balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 3µg/mL 125I-transferrin to measure surface binding sites. All data were corrected for nonspecific 125I-Tf binding, which was measured by incubating cells under the same conditions except that 600µg/mL unlabeled Tf was added. After a 2-h incubation on ice, the cells were washed six times, solubilized and surface-bound radioactivity was measured by gamma counting.

Down-regulation of cell surface LDL receptors

TVRb-1 cells were grown in 24-well plates for 3 days in Ham's F12 medium containing 10% lipoprotein-deficient mouse serum (a kind gift of Dr. Monty Krieger, MIT) to up-regulate expression of endogenous LDL receptors. On the day of the assay, cells (~ 40% confluency) were washed twice in serum-free Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 25mm HEPES, pH7.4, and pretreated with 10µm 16D10 or DMSO (0.1%) for 30min at 37°C. The cells were then placed on ice, washed twice to remove compound, and then incubated for 60 min with 25µg/mL of human LDL labeled with 125I on the apoliprotein moiety (also generously provided by Dr. Krieger). Unbound 125I-LDL was washed away with PBS and cells were lysed in 0.1 N NaOH. Cell-associated radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting and cell protein was measured using the Bradford assay (44) to calculate the amount of LDL bound to the cells (ng 125I-LDL/mg cell protein). Data was corrected for nonspecific binding determined in the presence of 40- fold excess nonlabeled LDL.

Tf receptor recycling kinetics

The kinetics of Tf receptor recycling in TRVb-1 cells were measured as previously described (45). Briefly, on the second day after plating into 24-well plates, cells were incubated with 3µg/mL 125I-Tf in serum-free McCoy's medium for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. This medium contains 20 mm HEPES and 26 mm sodium bicarbonate. Compounds were added at 50µm final concentration during the last 30min of incubation. In control samples, DMSO (vehicle) was added to final concentration of 0.5%. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were washed once with serum-free McCoy's medium, washed with a mild acid wash at pH5 for 2min, and then washed three times with HBSS. The cells were then incubated in serum-free McCoy's media supplemented with 100µm desferrioxamine and 3µg/mL of unlabeled Tf. The release of Tf from cells was monitored as a function of time by collecting the medium and solubilizing cells to measure 125I-Tf released and remaining in cells, respectively. The recycling rate constant for the Tf receptor was determined from plots of the natural log of the fraction of cell-associated Tf vs. time. Nonspecific binding was measured by incubating cells with 3µg/mL of 125I-Tf and 600µg/mL unlabeled Tf. All data were corrected for nonspecific 125I-Tf binding.

Endosomal pH measurements

TRVb-1 cells were plated in McCoy's 5A medium supplemented with 5% FBS on coverslip bottom dishes 2 days before experiments. On the day of the experiment, the cells were incubated with 20µg/mL rhodamine/fluorescein-labeled Tf (Rh/Fl-Tf) for 90min at 37 °C. Compounds or vehicle (0.5% DMSO) were added at 50µm during the final 30min of incubation. One dish was incubated for 90min in serum-free McCoy's 5A medium without any additions to determine background fluorescence. At the end of the incubation, samples were washed four times over 1 min with HBSS, transferred to the microscope stage and imaged live. A field of cells was chosen in the rhodamine channel, and a rhodamine and fluorescein images were collected. Images from five fields for each condition were collected. Samples were examined sequentially and loading times were staggered to insure that the incubation periods were constant among the different samples.

To correlate the Rh/Fl ratio with pH values, an in-cell calibration curve was constructed. Cells were incubated with 20µg/mL Rh/Fl-Tf for 90 min, washed four times with HBSS, and fixed for 5 min in 3.7% formaldehyde. Each sample was transferred to a different pH buffer (6.2, 6.6, 6.8, or 7.2) containing 40 mm methylamine. After a 1-h incubation, during which time the endosome pH equilibrates with the buffer pH, fluorescein and rhodamine images were collected from each dish (three fields per dish).

Images were collected on a Axiovert 200M inverted microscope using a 40×, 1.3 NA oil immersion objective (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY), and a cooled CCD-camera 1300-V/HS from Princeton Instruments, Inc. (Monmouth Junction, NJ). In all experiments the exposure times were set such that less than 5% of the pixels were saturating in the brightest samples. Images were processed using Metamorph image processing software (Universal Imaging Corp.) as described previously (46). The intensity of the pixels of the endosomes was measured by encircling the peri-centriolar endosome recycling compartment. The average pixel intensity was determined and background corrected by subtracting average pixel intensity from dishes that were not incubated with Rh/Fl-Tf. The ratio of rhodamine to fluorescein was calculated per endosomal recycling compartment and averaged values are presented.

Measurement of endocytosed β-galactosidase activity

K562 cells were washed three times in PBS and suspended in uptake buffer (150mm NaCl, 25 mm HEPES, pH7.4, 1 mg/mL dextrose, 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin [BSA]) with 0.5 mg/mL avidin-linked β-galactosidase as previously described (19). Internalization of the fluid phase endocytic marker was allowed to proceed for 60 min at 20 °C to permit accumulation into early endosomes. After extensive washing to remove any noninter-nalized marker, cells (5×106/mL) were resuspended in uptake buffer without BSA but with vehicle (1% DMSO) or 10µm 16D10. For comparison, cells were also treated with 20 mm NH4Cl or 500 nm bafilomycin A1. After continued incubation at 20 °C for 30 min, control cells were chilled on ice, while a paired sample was warmed to 37 °C to permit traffic to later compartments of the endocytic pathway. After 60 min incubation, the latter samples were also placed on ice, and along with control samples, cells were washed three times in ice-cold PBS, resuspended in hypotonic breaking buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH7.4, 100mm KCl, 85 mm sucrose, 20 mm EGTA), and snap-frozen in liquid N2. Samples were stored at −80°C until β-galactosidase activity was measured.

To obtain cell lysates, samples were thawed at room temperature, then placed on ice and vigorously vortexed for 1–2 min, then snap-frozen again. This procedure was repeated two times until > 90% of the cells were broken. Post-nuclear supernatants were collected upon centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Aliquots of 10 µL of the cell lysates were removed for β-galactosidase assays. Lysates were solubilized with 1 % octyl glucoside and enzyme assays were performed as previously described using the fluorogenic substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glactoside (19). Fluorescence (355 nm excitation; 460 nm emission) was measured using a SpectraMAX Gemini XS plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Measurement of ATPase activity

ATPase activity was measured as the liberation of 32Pi from (γ-32P)ATP (Amersham) (47). In brief, purified V-ATPase from bovine brain (21), 1 µg protein for each assay, was first mixed with 2µg phosphatidylserine and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The ATP hydrolysis assay was started by addition of 200 µL assay solution (30 mm KCl, 50 mm Tris-MES, pH7.0, 3mm MgCl2, and 3mm [γ-32P]ATP (400 cpm/nmol)) in the presence or absence of sulfonamide compounds at designated concentrations and continued for 15min at 37 °C. For ATPase assay of the dissociated catalytic sector V1 there is no need to incubate the enzyme with phosphatidylserine and Ca-ATPase activity was measured instead of Mg-ATPase activity, by replacing MgCl2 with 3 mm CaCl2. The ATP hydrolysis reaction was terminated by adding 1.0 mL of 1.25N perchloric acid, and the released 32Pi was extracted and counted in a Beckman scintillation counter as described (33).

Reconstitution of V-pump into proteoliposomes and measurement of proton translocation

The purified bovine brain V-ATPase was reconstituted into liposomes, which contain phosphatidylcholine, phosphati-dylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine and cholesterol at a weight ratio of 40:26.5:7.5:26, by the cholate dilution, freeze-thaw method (21). In brief, liposomes (200µg) were added to 1 µg of V-ATPase and were well mixed. Glycerol, Na-cholate, KCl, and MgCl2 were added to the protein–lipid mixture at final concentrations of 10% (v/v), 1%, 0.15 m and 2.5 mm, respectively. The reconstitution mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h, frozen in liquid N2 for 1 min, thawed at room temperature and ready for assay. Proton translocation was measured using the Acri-dine orange quenching (48), which was conducted in an SLM-Aminco DW2C dual wavelength spectrophotometer and the activity was registered as ΔA492-540. The mixture was diluted into 1.5mL of proton pumping assay buffer (150mm KCl, 10 mm Na-tricine, pH7.0, 3mm MgCl2, and 6.7 µm Acridine orange) in a spectrophotometer cuvette, which allows the formation of sealed proteoliposomes. The reaction was initiated by addition of 1.3 mm ATP (pH7.0) and 1 µg/mL valinomycin and continued for 5 min. Inhibitors were added into the assay solution either prior to the start or at the end of the assay.

Measurement of proton ionophore activity

Proton ionophore activity of sulfonamides was examined by their ability to collapse the proton gradient generated by the proteoliposomes of V-ATPase as described above, and by a direct measurement of the membrane potential-driven proton conductance of these compounds in a protein-free liposomes system. The membrane potential was established by loading the liposomes with 150mm KCl and diluting into a solution containing NaCl instead of KCl, which will generate a membrane potential, internal negative, in the presence of valinomycin, a potassium ionophore. This membrane potential will drive a proton influx if a mechanism for proton conductance is present, either a proton channel or a proton ionophore, which has been previously used to study the proton channel activity of V0 (49). In brief, the liposomes were reconstituted as described above, except that a buffer without protein was used instead of V-ATPase. The liposomes were sealed by dilution into 150mm KCl, 10 mm Na-tricine, pH 7.0, and 2 mm MgCl2, followed by centrifugation at 100 000 × €g for 1 h to precipitate the sealed liposomes that were loaded with KCl and suspended in a small volume of the same buffer. The proton conductance assay was performed using Acridine orange quenching as described above, except that the assay solution contains 150mm NaCl in place of KCl. Specifically, an aliquot of the above sealed liposomes containing 100µg lipids was added into an assay solution containing 150mm NaCl, 10 mm Na-tricine, pH7.0, 2mm MgCl2, 6.7 µm Acridine orange, and 1 µm valinomycin, and the compound to be assayed was added into the cuvette, after a stable baseline was established, to measure the proton conductance of the compound.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jenny Hoang for technical help in some of the sulfonamide dose-response experiments and Drs. George Quellhorst and Jan Cerny for their helpful discussions during the course of this investigation. The assistance of the Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology at Harvard Medical School is greatly appreciated. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK56160 and DK55495 (M.W.-R), GM36548 and GM62566 (T.K), DK52852 and DK57689 (T.E.M), and DK33627 (X.-S.X).

References

- 1.Specht KM, Shokat KM. The emerging power of chemical genetics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:155–159. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stockwell BR. Frontiers in chemical genetics. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18:449–455. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01499-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stockwell BR. Chemical genetics: ligand-based discovery of gene function. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:116–125. doi: 10.1038/35038557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng Y, Yu S, Lasell TK, Jadhav AP, Macia E, Chardin P, Melancon P, Roth M, Mitchison T, Kirchhausen T. Exo1: a new chemical inhibitor of the exocytic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6469–6474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631766100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yarrow JC, Feng Y, Perlman ZE, Kirchhausen T, Mitchison TJ. Phenotypic screening of small molecule libraries by high throughput cell imaging. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2003;6:279–286. doi: 10.2174/138620703106298527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karin M, Mintz B. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin in developmentally totipotent mouse teratocarcinoma stem cells. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:3245–3252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klausner RD, Van Renswoude J, Ashwell G, Kempf C, Schechter AN, Dean A, Bridges KR. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin in K562 cells. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:4715–4724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bali PK, Aisen P. Receptor-induced switch in site-site cooperativity during iron release by transferrin. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3963–3967. doi: 10.1021/bi00131a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciechanover A, Schwartz AL, Dautry-Varsat A, Lodish HF. Kinetics of internalization and recycling of transferrin and the transferrin receptor in a human hepatoma cell line. Effect of lysosomotropic agents. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:9681–9689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dautry-Varsat A, Ciechanover A, Lodish HF. pH and the recycling of transferrin during receptor-mediated endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:2258–2262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klausner RD, Ashwell G, van Renswoude J, Harford JB, Bridges KR. Binding of apotransferrin to K562 cells: explanation of the transferrin cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:2263–2266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruenberg J, Maxfield FR. Membrane transport in the endocytic path way. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:552–563. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inman RS, Wessling-Resnick M. Characterization of transferrin-independent iron transport in K562 cells. Unique properties provide evidence for multiple pathways of iron uptake. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8521–8528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez JA, Inman RS, Akompong T, Yu J, Wessling-Resnick M. Metabolic depletion inhibits the uptake of nontransferrin-bound iron by K562 cells. J Cell Physiol. 1998;177:585–592. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199812)177:4<585::AID-JCP9>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiley HS, Cunningham DD. The endocytotic rate constant. A cellular parameter for quantitating receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:4222–4229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klausner RD, van Renswoude J, Kempf C, Rao K, Bateman JL, Robbins AR. Failure to release iron from transferrin in a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant pleiotropically defective in endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:1098–1101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.3.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson LS, Dunn KW, Pytowski B, McGraw TE. Endosome acidification and receptor trafficking: bafilomycin A1 slows receptor externalization by a mechanism involving the receptor's internalization motif. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1251–1266. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.12.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Presley JF, Mayor S, McGraw TE, Dunn KW, Maxfield FR. Bafilomycin A1 treatment retards transferrin receptor recycling more than bulk membrane recycling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13929–13936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wessling-Resnick M, Braell WA. The sorting and segregation mechanism of the endocytic pathway is functional in a cell-free system. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:690–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weisz OA. Acidification and protein traffic. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;226:259–319. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(03)01005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crider BP, Xie XS. Characterization of the functional coupling of bovine brain vacuolar-type H+-translocating ATPase. Effect of divalent cations, phospholipids, and subunit H (SFD) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44281–44288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klausner RD, Donaldson JG, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Brefeldin A. insights into the control of membrane traffic and organelle structure. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1071–1080. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan EH. Inhibition of reticulocyte iron uptake by NH4Cl and CH3NH2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;642:119–134. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harford J, Wolkoff AW, Ashwell G, Klausner RD. Monensin inhibits intracellular dissociation of asialoglycoproteins from their receptor. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1824–1828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.6.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harford J, Bridges K, Ashwell G, Klausner RD. Intracellular dissociation of receptor-bound asialoglycoproteins in cultured hepatocytes. A pH-mediated nonlysosomal event. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:3191–3197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz AL, Bolognesi A, Fridovich SE. Recycling of the asialoglycoprotein receptor and the effect of lysosomotropic amines in hepatoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:732–738. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.2.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zijderhand-Bleekemolen JE, Schwartz AL, Slot JW, Strous GJ, Geuze HJ. Ligand- and weak base-induced redistribution of asialoglycoprotein receptors in hepatoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1647–1654. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.6.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tolleshaug H, Berg T. Chloroquine reduces the number of asialo-glycoprotein receptors in the hepatocyte plasma membrane. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979;28:2919–2922. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu SK, Goldstein JL, Anderson RG, Brown MS. Monensin interrupts the recycling of low density lipoprotein receptors in human fibroblasts. Cell. 1981;24:493–502. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins. a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7972–7976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drose S, Bindseil KU, Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Zeeck A, Altendorf K. Inhibitory effect of modified bafilomycins and concanamycins on P- and V-type adenosine triphosphatases. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3902–3906. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd MR, Farina C, Belfiore P, Gagliardi S, Kim JW, Hayakawa Y, Beutler JA, McKee TC, Bowman BJ, Bowman EJ. Discovery of a novel antitumor benzolactone enamide class that selectively inhibits mammalian vacuolar-type (H+)-ATPases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie XS, Stone DK, Racker E. Proton pump of clathrin-coated vesicles. Meth Enzymol. 1986;157:634–646. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A, Moriyama Y, Futai M, Tashiro Y. Bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase, inhibits acidification and protein degradation in lysosomes of cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17707–17712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moriyama Y, Nelson N. H+-translocating ATPase in Golgi apparatus. Characterization as vacuolar H+-ATPase and its subunit structures. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18445–18450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llopis J, McCaffery JM, Miyawaki A, Farquhar MG, Tsien RY. Measurement of cytosolic, mitochondrial, and Golgi pH in single living cells with green fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6803–6808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Weert AW, Geuze HJ, Groothuis B, Stoorvogel W. Primaquine interferes with membrane recycling from endosomes to the plasma membrane through a direct interaction with endosomes which does not involve neutralisation of endosomal pH nor osmotic swelling of endosomes. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:394–399. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Weert AW, Dunn KW, Gueze HJ, Maxfield FR, Stoorvogel W. Transport from late endosomes to lysosomes, but not sorting of integral membrane proteins in endosomes, depends on the vacuolar proton pump. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:821–834. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.4.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palokangas H, Metsikko K, Vaananen K. Active vacuolar H+ATPase is required for both endocytic and exocytic processes during viral infec tion of BHK-21 cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17577–17585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kataoka T, Muroi M, Ohkuma S, Waritani T, Magae J, Takatsuki A, et al. Prodigiosin 25-C uncouples vacuolar type H+-ATPase, inhibits vacuolar acidification and affects glycoprotein processing. FEBS Lett. 1995;359:53–59. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kane PM, Parra KJ. Assembly and regulation of the yeast vacuolar H (+) -ATPase. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:81–87. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wieczorek H, Grber G, Harvey WR, Huss M, Merzendorfer H, Zeiske W. Structure and regulation of insect plasma membrane H+ V-ATPase. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:127–135. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGraw TE, Greenfield L, Maxfield FR. Functional expression of the human transferrin receptor cDNA in Chinese hamster ovary cells deficient in endogenous transferrin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:207–214. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson AO, Subtil A, Petrush R, Kobylarz K, Keller SR, McGraw TE. Identification of an insulin-responsive, slow endocytic recycling mechanism in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17968–17977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunn KW, Park J, Semrad CE, Gelman DL, Shevell T, McGraw TE. Regulation of endocytic trafficking and acidification are independent of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5336–5345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie XS, Stone DK. Isolation and reconstitution of the clathrin-coated vesicle proton translocating complex. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:2492–2495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gluck S, Kelly S, Al-Awqati Q. The proton translocating ATPase responsible for urinary acidification. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:9230–9233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crider BP, Xie XS, Stone DK. Bafilomycin inhibits proton flow through the H+ channel of vacuolar proton pumps. J Biol Chem. 2000;269:17379–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]