Kidney cancer, predominantly renal cell carcinoma (RCC), is the most lethal genitourinary malignancy and kills more that 1500 Canadians annually.1 The overall incidence is increasing by 2% per year for unknown reasons. There have been major advances in systemic therapy with newly introduced targeted agents in local therapy with minimally invasive surgery and image-guided ablative physical technologies in imaging, pathology and molecular genetics. These have revolutionized care and stimulated research and discovery. There are at least 4 sets of guidelines in Canada today that address various aspects of RCC patient care.2,3,4,5

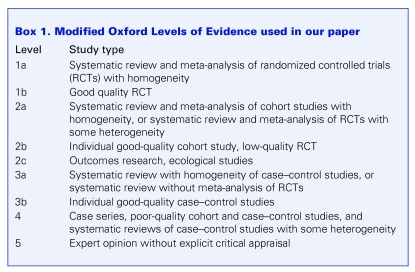

A consensus meeting of Canadian experts in kidney cancer was held from Jan. 31 to Feb. 2, 2008, in Mont Tremblant, Quebec. About 60 Canadian experts, including multidisciplinary kidney cancer clinicians (urologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, oncology nurses, medical imagers, pathologists and a clinician scientist), 3 senior pharmaceutical industry executives and patients representing the newly founded Kidney Cancer Canada, attended the meeting by invitation. Key references in each area were provided by experts in each area and were graded using a modified version of the Oxford Levels of Evidence (Box 1).

Box 1.

During the conference, content experts presented reports, which were followed by questions, discussion and voting to achieve consensus as necessary.

This first report from the forum addresses the management of patients with localized, locally advanced and metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). It is formatted in a series of statements representing the consensus of the forum attendees, based on available evidence.

Initial evaluation and management of localized kidney cancer

The incidence of early-stage kidney cancer is increasing, in part due to the widespread use of abdominal imaging.3

Diagnosis and staging

Diagnosis and staging of RCC should include:

History and physical examination

Laboratory tests: CBC, LDH, metabolic panel (creatinine, electrolytes, AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, INR, PTT, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, albumin), urinalysis and urine cytology

Imaging

Primary tumour

Abdominal/pelvic CT with and without intravenous contrast

Abdominal MRI if CT suggests caval thrombus or because of a contrast allergy or renal insufficiency

Metastatic evaluation

Chest radiograph, consider CT chest if ≥ stage T2

Bone scan, if clinically indicated or elevated alkaline phosphatase

Brain MRI, if clinically indicated

A suspicious renal mass that enhances by CT scanning is usually considered an RCC for treatment planning. Most new tumours are asymptomatic and undetectable on examination but may be associated with pain, hematuria or a flank mass. Metastases at presentation are rare.

The 2002 TNM staging system should be used.6

Role of renal biopsy

Biopsy for histological diagnosis may be considered before treatment of small (< 3 cm) enhancing solid tumours in patients with significant comorbities or limited life expectancy.

There is growing experience with percutaneous needle core biopsy of early stage renal tumours indicating that it is relatively safe and diagnostic in most cases.7 This is not yet a standard of care and requires local expertise with image-guided biopsy techniques and pathological interpretation.

Treatment options

Stage T1a

Open partial nephrectomy recommended

Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy in experienced centres

Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy

Probe ablation by radiofrequency (RFA) or cryotherapy

Active surveillance

Surgical resection remains the only curative therapy for localized disease. There is no high-level evidence for the superiority of any one surgical technique. However, laparoscopic radical nephrectomy is a less morbid procedure than open and should be considered where expertise is available. Partial nephrectomy provides recurrence-free and long-term survival rates similar to radical nephrectomy for tumours < 4 cm in diameter.8,9,10 Further, partial nephrectomy is associated with a lower risk of long-term renal dysfunction.11 There is preliminary experience with HIFU (high intensity focussed ultrasound), but probe ablation by RFA and cryotherapy has been extensively reported with promising early results in terms of efficacy and side effects.12,13

Stage T1b

Radical nephrectomy: laparoscopic (open if lack of expertise available)

Partial nephrectomy

Although there is emerging evidence to suggest equivalent oncological results with partial nephrectomy for tumours 4–7 cm,10 there is currently insufficient data to recommend this electively and thus laparoscopic radical nephrectomy is the surgery of choice in this setting.

Stage T2

Radical nephrectomy: open or laparoscopic

Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy can be safely performed selectively for tumours greater than 7 cm.14 Open radical nephrectomy remains the standard for large renal masses.

These recommendations are based on expert opinion that is currently broadly supported in Canada and elsewhere.

Active surveillance as a treatment option

The safety of initial active surveillance with delayed treatment for progression is not yet established. However, it is an alternative for managing small renal masses (SRMs) that are asymptomatic and characteristic of RCC on imaging in the elderly, infirm or both. Follow-up must include serial imaging. It is not yet recommended for the young and fit.

Active surveillance is currently being studied in a multicentre phase 2 trial in Canada.15 This is widely practised for the aforementioned patient population, but reliable prognostic factors for progression to metastatic disease are not presently defined, which makes this approach unsafe for the younger and fit patients.

Surveillance schedules after radical or partial nephrectomy

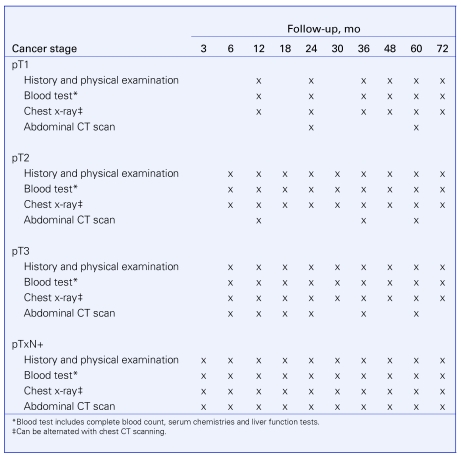

We are following the CUA Guidelines 2008 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Follow-up schedules.37

Management of locally advanced kidney cancer

Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy

There is no indication for adjuvant therapy following complete resection or neoadjuvant therapy before resection outside of clinical trials.

Recommendations for this section are based on Level I evidence. To date, very few randomized trials that have investigated the role of cytokine therapy as adjuvant treatment for patients with completely resected RCC are available. Adjuvant therapy with cytokines does not improve overall survival (OS) after nephrectomy.16 (Level 1b evidence) The results of clinical trials with adjuvant and neoadjuvant anti-angiogenic agents (tyrosine kinase inhibitors [TKIs], and VEGF or mTOR inhibitors) are not yet available. Patients with high-risk tumours who have undergone complete resection, should be asked to participate in clinical trials whenever possible.

Role of lymphadenectomy

Lymphadenectomy is optional for clinical N0M0 disease.

In N+M+ and N+M0 patients undergoing nephrectomy, lymphadenectomy including all abnormal nodes should be performed and submitted separately for staging.

The incidence of occult positive lymph nodes is 3%–5% in patients with cT1–2 N0M0 tumours and 10%–20% with cT3–4 N0M0 tumours.17 After proper preoperative staging, the incidence of unsuspected lymph node metastases is low (about 3%).

There is no evidence that patients with clinical stage N0M0 disease benefit from a hilar or regional lymphadenectomy. However, important prognostic information for patients with locally advanced disease may be obtained.17

Lymphadenectomy should be restricted to the perihilar tissue for staging purposes in patients with stage N0M0. Extended lymphadenectomy has not been demonstrated to improve survival in these patients.

Retrospective data from patients with clinical stage TxN+M0 suggest a clinical benefit with extended lymphadenectomy in selected patients with locally advanced disease.18 (Level 2b evidence) However, there is no agreement among clinicians regarding the extent of the dissection or lymphadenectomy template.

Role of adrenalectomy

Routine ipsilateral adrenalectomy at the time of nephrectomy is not recommended if the adrenal gland is normal sized on imaging and direct invasion by a large upper pole tumour is excluded.

The incidence of ipsilateral adrenal involvement is 1.9%–7.5%.19 Current imaging techniques are reported to have excellent specificity (92.1%–99.6%), sensitivity (88.8%–89.6%), negative predictive value (99.4%) and positive predictive value (34.7%–92.8%) for the identification of adrenal gland involvement.21 Metastatic disease to the ipsilateral adrenal gland as the only site of metastatic spread is low, in the range of 0.7%–2%. Only 0%–0.4% of these cases are not detected preoperatively. Tumour stage and presence of adrenal radiographical enlargement have been identified as prognostic factors. (Level 4 evidence) Ipsilateral adrenalectomy may be performed for patients with higher risk tumours such as stages T3–4, in particular if they are upper pole tumours and (or) N1–3, and (or) M1. (Level 4 evidence)

Management of the IVC and renal vein thrombus

In the absence of distant metastases, tumour thrombus should be resected to provide a chance of cure.

It is recommended that these patients' treatment be performed in or referred to a centre with experience as these potentially complex procedures have significant risk of morbidity and mortality.

About 4%–10% of all RCCs involve the inferior vena cava (IVC), and about 1% extend into the right atrium. RCCs with tumour thrombi tend to have a higher stage and grade. Distant or lymph node metastases are twice as common. At least 1 metastatic site is present in 30% of patients with vascular involvement. In the absence of distant metastases, surgery provides the only chance of cure for these patients. Retrospective case series have reported up to 70% 5-year survival rates. Little prospective data are available regarding the resection of venous thrombi.

Advanced metastatic kidney cancer (mRCC)

Enrolling patients in well-designed clinical trials should always be considered as the first option for patients with advanced or mRCC.

First-line therapy

Sunitinib is the first-line standard of care for patients with good or intermediate prognosis

Temsirolimus is the treatment option for poor-prognosis patients.

Observation can also be considered, as some patients who have slow-growing asymptomatic disease.

Recommendations for this paragraph are based on Level 1 evidence. Based on phase III data, sunitinib produces higher response rates, improved quality of life and a longer progression-free survival (PFS) than interferon (INF) in patients with clear cell carcinoma.21(Level 1b evidence) Based on phase III data, temsirolimus produces an improvement in PFS and OS in poorer risk patients than INF alone or the combination of temsirolimus and INF. Poorer risk was defined by at least 3 out of 6 of the following criteria: KPS > 60–70, ↑Ca2+, ↓Hgb, ↑LDH, < 1 year from nephrectomy to treatment, multiple metastatic sites.22 For patients unsuitable for sunitinib or temsirolimus, sorafenib is an option.23

In patients with metastatic or advanced RCC with nonclear cell pathology, options include sunitinib, based on subgroup analyses from the expanded access trial showing safety and activity;24 sorafenib, based on subgroup analyses from the Advabced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib (ARCCS) expanded access trial showing safety and activity;25 and temsirolimus, based on subgroup analysis of phase III data.26

In the opinion of forum attendees, observation is a reasonable option for patients with mRCC, especially given that no therapies are currently considered curative and that all available treatments can be associated with side effects.

When prescribing systemic therapy for advanced or mRCC, several key factors must be taken into account. An oncology specialist knowledgeable about the acute and long-term toxicities, drug interactions, monitoring treatment and response should prescribe therapy. Patients should be managed in a multidisciplinary environment with adequate nursing care, dietary care, pharmacy support, etc. Patients must be evaluated frequently to ensure toxicities are recognized and managed appropriately. Patients should be provided with information concerning potential side effects, prevention and treatment.

Low-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) and INF are no longer the standard of care.

High-dose IL-2 can be considered for extremely selected patients.

Recommendations for this section are based on Level I evidence. In the opinion of the conference attendees, INF still plays a role in the treatment of highly selected patients. The PERCY Quattro trial showed no significant differences in survival for the groups that received INF-α, IL-2, both or medroxyprogesterone showing little evidence to support the use of cytokines.27 A Cancer Care Ontario systematic review of randomized controlled trials of INF showed a very modest benefit to treatment with INF (CCO guideline, in press). INF has no role in nonclear cell pathology.

No phase III studies of the use of IL-2 have shown an improvement in survival; thus, it is not considered a standard of care. High-dose IL-2 must be delivered in specialized and experienced IL-2 treatment centres, ideally in the context of a clinical trial or investigational setting. Low-dose IL-2 should not be given.4,27 (Level 1a evidence;27 Level 1b evidence)

Progression on or intolerance to cytokines

In patients with advanced or metastatic disease who fail cytokines or cannot tolerate them, sorafenib is the preferred treatment

Recommendations for this section are based on Level I evidence. Based on phase III data, sorafenib improved PFS, compared with best supportive care alone, in previously treated patients. Overall survival data was confounded by crossover but reached significance when censored for crossover.23,28 Sunitinib is an alternate treatment. Based on 2 phase II trials, sunitinib produced significant response rates and increased PFS, compared with historical controls.21

Progression after first-line therapy

Switch to another TKI.

In patients with advanced or mRCC after sunitinib or sorafenib failure, options include switching to another TKI (e.g., from sunitinib to sorafenib or from sorafenib to sunitinib) based on emerging data showing activity with sequential therapy;29,30 switching to INF, based on limited data but activity in previous phase II studies (CCO guideline in press); and switching to temsirolimus, based on a small body of retrospective and phase II data.31

In patients with advanced or metastatic sarcomatoid or poorly differentiated RCC, options include sunitinib, based on prospective, nonrandomized data from the Expanded Access Program;24 sorafenib, based on prospective, nonrandomized data from the ARCCS expanded access trial;25,32 chemotherapy, based on phase II data using agents such as 5FU, gemcitabine, doxorubicin and combinations of these showing activity;33 and temsirolimus, based on subgroup analysis in from the pivotal phase III trial in which these patients were eligible.26

Surgery and radiotherapy

Cytoreductive nephrectomy is recommended to improve OS in appropriately selected patients with mRCC planned to receive INF-α immunotherapy.

Recommendations for this section are based on Level I evidence. Appropriately selected patients for cytoreductive nephrectomy include patients with a primary tumour of clear cell histology amenable to surgical extirpation and a low risk of perioperative morbidity, patients with good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1) and patients without evidence of brain metastases.4,34,35

Recognizing that most patients will be planned for TKI therapy rather than cytokine therapy, further study of the true benefit of cytoreductive nephrectomy is required. While this question may be addressed in planned clinical trials, there are no data to guide clinical practices at this time. Decisions are to be made based on clinical indications. Nephrectomy will likely not be harmful based on the fact that about 90% of enrolled patients received nephrectomy before systemic therapy in both the sunitinib and the sorafenib phase III trials.21,23 In patients with response to TKI or targeted therapy, limited metastatic disease and good performance status, it is reasonable that cytoreductive nephrectomy be considered.

In select patients with limited sites of metastatic disease and clinical stability, resection of the metastatic disease may be reasonable.

A 5-year survival rate as high as 50% has been reported in patients with resected solitary pulmonary metastasis.36 There is little published data regarding resection of minimal residual disease after a response to TKI therapy, but consideration of this approach is reasonable in selected cases.

Radiation therapy may be considered to control bleeding and pain from the primary tumour, palliate symptoms from metastases and stabilize brain metastases.

Radiation may be considered in select patients with positive surgical margins. Clinical trials involving radiation should be supported.

Discussion

Key references were presented and discussed by invited guests, speakers and conference attendees. Conference attendees discussed the evidence surrounding the use of inhibitors of angiogenesis and cytokines. With respect to angiogenesis inhibitors, this new class of drugs has gained considerable attention for its impact on the survival of RCC patients. While much of the data were still only available in abstract form, 3 randomized controlled trials were published in complete form in 2007.21,22,23 The group also reviewed a systematic review by Cancer Care Ontario concerning the use of angiogenesis inhibitors.

In a phase III trial by Motzer and colleagues,21 750 patients who had not received previous treatment for RCC were randomized to receive either sunitinib or INF-α. PFS was longer and response rates were higher in patients with mRCC who received sunitinib than in those receiving INF-α, and sunitinib was also associated with a higher quality of life than for those patients receiving INF-α.

In a phase III randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study,23 903 patients who were resistant to previous therapy were randomized to receive either sorafenib or placebo. Treatment with sorafenib improved OS, although the difference was not significant; however, PFS rates were significant in the group treated with sorafenib, so patients were allowed to cross over.

In a phase III study by Hudes and colleagues,22 626 patients with previously untreated poor prognosis RCC were randomized to receive treatment with either temsirolimus, INF-α or a combination of the 2 drugs. Patients who received temsirolimus alone showed better OS and PFS than patients who received INF-α alone or the combination therapy. Patients in the temsirolimus group also suffered from fewer adverse events.

A number of American Society of Clinical Oncology abstracts were also discussed.24,25,29,32 One was a retrospective review of patients who had received sequential treatment with sorafenib and sunitinib, one was a preliminary toxicity analysis of a subgroup in an expanded access trial and one presented results from the sorafenib expanded access trial.24,25,29,32

Conference attendees agreed that angiogenesis inhibitors should be used as a first-line treatment for RCC when available; however, new emerging issues surrounding the use of angiogenesis inhibitors were discussed. Concern was expressed that there were currently no clear guidelines as to when to discontinue drug treatment and if it was safe to remove a patient from treatment once there was no evidence of disease. There is only anecdotal evidence to support the theory that patients may flare after discontinuing treatment, and only anecdotal evidence to support that patients do not develop sensitivity to the drug. Concern was also expressed based on anecdotal evidence that the management of bone metastases was problematic in patients being treated with inhibitors of angiogenesis. Treatment of these bone metastases with bisphosphonates is unavailable in Canada, which raised additional concerns.

The role of cytokines in the era of angiogenesis inhibitors was also discussed. Participants examined the results of the PERCY Quattro trial, in which 492 patients were randomized to receive either medroxyprogesterone acetate, INF-α, IL-2 or both cytokines in a 2 × 2 factorial design. There were no significant differences in survival reported between the groups that received INF or IL-2, diminishing the evidence to support the use of cytokines.27 Further Cancer Care Ontario guidelines on the use of INF and IL-2 in RCC showed no survival benefit for low-dose IL-2, and only a modest survival benefit for treatment with INF (Cancer Care Ontario, in press).

Participants questioned whether the use of cytokines still played a role in the treatment of RCC. Some participants believed that the newer angiogenesis inhibitors had made treatment using these older drugs obsolete, yet others believed that these older drugs should be included in the guidelines. Arguments for including cytokines in the guideline included ensuring that patients who did not have access to the newer treatments still had treatment options, and the argument that these drugs are the only treatments to produce durable, long-term remissions, albeit only in very rare cases. Finally, some argued that the role of INF should be included as new research was taking the drug in new potential directions, such as trials combining treatment with INF with treatment with bevicizumab, and that these trials showed promise.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society; National Cancer Institute of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics Toronto: National Cancer Institute of Canada; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.BC Cancer Agency. Cancer Management Guidelines Kidney 2007 Available: www.bccancer.bc.ca/HPI/CancerManagementGuidelines/Genitourinary/Kidney/start.htm(accessed 2008 May 5). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberta Cancer Board .Clinical Practice Guideline Renal Cell Carcinoma Available: www .cancerboard.ab.ca/Professionals/TreatmentGuidelines/Guidelines_Genitourinary/TreatmentGuidelines_Renal_Cell_Carcinoma.htm (accessed 2008 May 5). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Care Ontario. Genitourinary Cancer Practice Guidelines Available: www .cancercare.on.ca/english/toolbox/qualityguidelines/diseasesite/genito-ebs/ (accessed 2008 May 5). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Care Nova Scotia. Cancer Management Guidelines: management of kidney cancer Available: www.cancercare.ns.ca/inside.asp?cmPageID=232 (accessed 2008 May 5). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobin LH, Wittekind C, editors. NM classification of malignant tumours. 6th ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volpe A, Kachura JR, Geddie WR, et al. Techniques, safety and accuracy of sampling of renal tumors by fine needle aspiration and core biopsy. J Urol 2007;178:379-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novick AC. Laparoscopic and partial nephrectomy. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:6322s-7s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fergany AF, Hafez KS, Novick AC. Long term results of nephron sparing surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma. Br J Urol 2000;163:442-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Cheville JC, et al. Nephron sparing surgery for appropriately selected renal cell carcinoma between 4 and 7 cm results in outcome similar to radical nephrectomy. J Urol 2004;171:1066-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:735-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill IS, Remer EM, Hasan WA, et al. Renal cryoablation: outcome at 3 years. J Urol 2005;173:1903-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gervais, DS, Arellano RS, McGovern FJ, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma: part 2, lessons learned with ablation of 100 tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 85:72-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg AP, Finelli A, Desai MM, et al. Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy for large (greater than 7 cm, T2) renal tumors. J Urol 2004;172:2172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattar K, Basiuk J, Finelli A, et al. Active surveillance of small renal masses: a prospective multi-centre Canadian trial. Eur J Urol 2008;7(Suppl3):309 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messing EM, Manola J, Wilding G, et al. Phase III study of interferon alfa-NL as adjuvant for resectable renal cell carcinoma: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group/Intergroup trial. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1214-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terrone C, Guercio S, De Luca S, et al. The number of lymph nodes examined and staging accuracy in renal cell carcinoma. BJU Inl 2003;91:37-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pantuck AJ, Zisman A, Dorey F, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with retroperitoneal lymph nodes: impact on survival and benefits of immunotherapy. Cancer 2003;97:2995-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kletscher BA, Qian J, Bostwick DG, et al. Prospective analysis of the incidence of ipsilateral adrenal metastasis in localized renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 1996;155:1844-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Knobloch R, Seseke F, Riedmiller H, et al. Radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: Is adrenalectomy necessary? Eur Urol 1999;36:303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motzer RJ, Huston TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. New Eng J Med 2007;356:115-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2271-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:125-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gore ME, Porta C, Oudard S, et al. Sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): preliminary assessment of toxicity in an expanded access trial with subpopulation analysis. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(18S):5010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knox JJ, Figlin RA, Stadler WM, et al. The Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib (ARCCS) expanded access trial in North America: safety and efficacy. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(18S):5011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dutcher JP, Szczylik C, Tannir N, et al. Correlation of survival with tumor histology, age, and prognostic risk group for previously untreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (adv RCC) receiving temsirolimus (TEMSR) or interferon-alpha (IFN). J Clin Oncol 2007;25(18S):5033. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negrier S, Perol D, Ravaud A, et al. Medroxyprogesterone, interferon alfa-2a, interleukin 2, or combination of both cytokines in patients with metastatic renal carcinoma of intermediate prognosis: results of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2007;110:2468-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bukowski RM, Eisen T, Szczylik C, et al. Final results of the randomized phase III trial of sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma: survival and biomarker analysis. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(18S):5023. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sablin MP, Bouaita L, Balleyguier C, et al. Sequential use of sorafenib and sunitinib in renal cancer: retrospective analysis in 90 patients. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(18S):5038. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamaskar I, Garcia JA, Elson P, et al. Antitumor effects of sunitinib or sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received prior antiangiogenic therapy. J Urol 2008;179:81-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, et al. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:909-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stadler WM, Figlin RA, Ernstof MS, et al. The Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib (ARCCS) expanded access trial: safety and efficacy in patients (pts) with non-clear cell (NCC) renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol 2007;25(18S):5036. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nanus DM, Garino A, Milowsky MI, et al. Active chemotherapy for sarcomatoid and rapidly progressing renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2004;101:1545-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flanigan RC, Mickisch G, Sylvester R, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis. J Urol 2004;171:1071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mickisch GH. Urologic approaches to metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Onkologie 2001;24:122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kavolius JP, Mastorakos DP, Pavlovich C, et al. Resection of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canadian Urological Association follow-up guidelines after radical or partial nephrectomy for localized and locally advanced renal cell carcinoma Available: www.cua.org/guidelines/rccc-proposed_e.pdf (accessed 2008 May 5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]