Abstract

In previous studies, we determined that β1 integrins from human colon tumors have elevated levels of α2-6 sialylation, a modification added by β-galactosamide α-2,6-sialyltranferase I (ST6Gal-I). Intriguingly, the β1 integrin is thought to be a ligand for galectin-3 (gal-3), a tumor-associated lectin. The effects of gal-3 are complex; intracellular forms typically protect cells against apoptosis through carbohydrate-independent mechanisms, whereas secreted forms bind to cell surface oligosaccharides and induce apoptosis. In the current study, we tested whether α2-6 sialylation of the β1 integrin modulates binding to extracellular gal-3. Herein we report that SW48 colonocytes lacking α2-6 sialylation exhibit β1 integrin-dependent binding to gal-3-coated tissue culture plates; however, binding is attenuated upon forced expression of ST6Gal-I. Removal of α2-6 sialic acids from ST6Gal-I expressors by neuraminidase treatment restores gal-3 binding. Additionally, using a blot overlay approach, we determined that gal-3 binds directly and preferentially to unsialylated, as compared with α2-6-sialylated, β1 integrins. To understand the physiologic consequences of gal-3 binding, cells were treated with gal-3 and monitored for apoptosis. Galectin-3 was found to induce apoptosis in parental SW48 colonocytes (unsialylated), whereas ST6Gal-I expressors were protected. Importantly, gal-3-induced apoptosis was inhibited by function blocking antibodies against the β1 subunit, suggesting that β1 integrins are critical transducers of gal-3-mediated effects on cell survival. Collectively, our results suggest that the coordinate up-regulation of gal-3 and ST6Gal-I, a feature that is characteristic of colon carcinoma, may confer tumor cells with a selective advantage by providing a mechanism for blockade of the pro-apoptotic effects of secreted gal-3.

Aberrant cell surface carbohydrates are highly associated with tumor invasion and metastasis. In particular, N-linked glycans on tumor cells tend to be more highly branched, with greater levels of terminal sialylation (1-5). The ST6Gal-I2 sialyltransferase, which adds α2-6-linked sialic acids to glycoproteins (4, 6), is up-regulated in a number of tumors including colon adenocarcinoma, and its expression positively correlates with tumor metastasis and poor patient survival (4, 5, 7). Moreover, both in vitro and animal studies have implicated ST6Gal-I in regulating tumor cell invasiveness and metastasis (7-10). However, the mechanisms linking elevated α2-6 sialylation to tumor progression are still poorly understood. Previously, our group identified the β1 integrin subunit as a target for oncogenic Ras-induced ST6Gal-I activity (11) and further determined that α2-6 sialylation of β1 integrins stimulated cell attachment and migration on collagen I (12). We also reported that β1 integrins in colon tumor tissues carry elevated levels of α2-6-linked sialic acid (12). Collectively, these results suggest that hypersialylation of the β1 integrin may contribute to the invasive tumor cell phenotype by modulating cell-matrix interactions.

There is a vast literature directed at understanding integrin association with traditional extracellular matrix ligands such as collagen, fibronectin, etc. However, accumulating data suggest that integrins also bind to galectins, a family of lectins that can associate with the matrix through interactions with laminin and fibronectin (13, 14). Galectins are β-galactoside-binding proteins that bind to target molecules through conserved carbohydrate recognition domains. So far, at least 15 mammalian galectins have been identified, and these are known to regulate numerous biological processes including cell adhesion/migration, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and immune responses (13, 15). One unique member of the galectin family is galectin-3 (gal-3), which has only one carbohydrate recognition domain, in combination with an extended N-terminal domain that is thought to promote oligomerization (16). Galectin-3 is expressed intracellularly but can also be secreted through a nonclassical pathway (17). Intracellular gal-3 generally mediates anti-apoptotic effects through carbohydrate-independent processes, whereas extracellular gal-3 binds to cell surface oligosaccharides and thereby induces apoptosis and also modulates cell-matrix interactions (15, 16, 18). Given the diverse locales and functions of gal-3, the ultimate effect of this lectin on tumor cell behavior, and particularly survival, likely depends upon the balance of signals arising from intracellular versus extracellular gal-3.

Like ST6Gal-I, gal-3 appears to play important roles in neoplastic cell metastasis. Transfection of gal-3 into low metastatic colon cancer cells enabled the cells to become more metastatic after inoculation into spleen or cecum of nude mice. In contrast, transfection of antisense gal-3 into a highly metastatic colon cancer cell line reduced metastatic capability (19). Galectin-3 is reported to be highly expressed in several tumor types including colon carcinoma, and up-regulated gal-3 expression is associated with tumor aggressiveness (15, 16).

Several studies have suggested that galectin binding to β-galactosides may be sensitive to terminal sialylation. For example, Hirabayashi's group (20) used frontal affinity chromatography to show that the binding of gal-3 to synthetic oligosaccharides (as opposed to cellular glycoproteins) could occur in the presence of α2-3, but not α2-6, sialylation of β-galactose. Studies of immune cells support this general concept; cell surface α2-6 sialylation was reported to block apoptosis induced by galectin-1 (gal-1) (21, 22). However, the potential roles of gal-3 and ST6Gal-I in regulating epithelial cell survival have received little attention despite the fact that both gal-3 and ST6Gal-I are implicated in tumor progression. Accordingly, we compared the effects of gal-3 on SW48 cells that either lack endogenous ST6Gal-I (parental cells) or have forced expression of ST6Gal-I. These studies showed that gal-3 preferentially binds to cells with unsialylated β1 integrins. Moreover, α2-6 sialylation of the β1 integrin was found to protect cells against gal-3-mediated cell apoptosis, implicating a role for ST6Gal-I in regulating tumor cell survival.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines—The human SW48 colon epithelial cell line was purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). These cells are derived from a stage IV colon adenocarcinoma, and subcutaneous inoculation of SW48 cells into nude mice reportedly results in tumor formation 100% of the time (23). SW48 cells have no detectable α2-6 or α2-3 sialyltransferase activity (24). SW48 cells stably expressing either empty vector (EV) or ST6Gal-I (ST6) were established as described previously using a lentiviral vector (12), and pooled populations of lentiviral-infected clones were utilized for all studies. The cells were grown in Leibovitz's L-15 medium with 2 mmol/liter l-glutamine (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyglone, Logan, UT). EV and ST6 cells were maintained with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) in complete culture medium (the puromycin was removed from the medium at least 1 day in advance of all experiments). All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a CO2-free incubator.

Galectin-1/3 Cell Adhesion Assay—InnoCyte ECM adhesion assay gal-1/gal-3 kits were purchased from Calbiochem. According to the vendor, the wells were coated with 100 μl/well of either 5 μg/ml gal-1 or 5 μg/ml gal-3 in PBS followed by blocking with 2% BSA in PBS. BSA- and poly-l-lysine-coated wells were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The wells were never exposed to serum-containing medium during commercial processing. Cells were harvested by cell stripper (Mediatech) and washed extensively in PBS. Then the cells (at subconfluent density) were seeded onto each well in serum-free medium and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The 2-h attachment interval was selected because epithelial cells typically bind maximally to most substrates within 2 h. As well, allowing cells to adhere for longer time points increases the possibility that cells will secrete matrix molecules such as fibronectin or collagen, which could compromise the interpretation of results. After a 2-h incubation, cells were washed with PBS twice and labeled with calcein AM for 1 h at 37°C. The number of calcein AM-labeled cells was measured by VersaFluor fluorometer (Bio-Rad) at 520 nm. For some experiments, cells were incubated in the presence or absence of either lactose (Sigma) or sucrose (Bio-Rad). For the β1 integrin blocking study, 35 μg/ml function blocking antibodies against the β1 integrin (catalog number MAB1965, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) or a mouse IgG1 isotype control (R&D Systems) were preincubated with SW48 cells for 45 min at 37 °C prior to seeding cells onto the galectin-coated plates. All data were analyzed by a Student's paired t test.

Flow Cytometry—Cells were harvested by cell stripper (Mediatech) and were adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/tube with 100 μl of 0.2% BSA in PBS. 10 μl of FITC-conjugated anti-β1 integrin antibody (Chemicon International), FITC-conjugated mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen), or PBS only were added to each tube and incubated on ice for 60 min. The cells were washed three times with 0.2% BSA in PBS and resuspended in 500 μl of 0.2% BSA in PBS for flow cytometric analysis on FACScan (BD Biosciences).

Western Blotting—Cells were lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) with 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20. The membranes were incubated with a primary antibody against gal-1 (R&D Systems), gal-3 (R&D Systems), β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), or β1 integrins (BD Biosciences). The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences) and developed with Immobilon chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Neuraminidase Treatment of Cell Lysates—90 μg of cell lysates were treated in 50 mm sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in the presence or absence of different concentrations of neura-minidase from Clostridium perfringens (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) for 1 h at 37°C. The cell lysates were subsequently boiled in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for the β1 integrin (BD Biosciences).

Neuraminidase Treatment of Cells—4 × 105 cells were treated in the presence or absence of 50 units of neuraminidase from C. perfringens (New England Biolabs) in PBS (pH 7.0) for 1 h at 37 °C. Then the cells were washed three times with PBS and resuspended in serum-free culture medium for gal-3 cell adhesion assay.

Immunofluorescent Staining—Round German glass coverslips (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) were coated with 20 μg/ml collagen I (Inamed Biomaterials, Fremont, CA) overnight. The cells were plated on the collagen-coated coverslips for 3 h at 37°C and then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. The cells were treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min and blocked with 5% donkey serum. The cells were subsequently incubated with anti-gal-3 antibody (R&D Systems), no primary antibody, or mouse IgG2b isotype control (R&D Systems) for 1 h at room temperature followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) for 45 min at room temperature. The coverslips were mounted with Aqua-Poly/Mount medium (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA), and cells were viewed under ×60 oil objective of a fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were taken by a Nikon CoolSNAP camera.

Galectin-3 Overlay—Cell lysates (500 μg of total protein/sample) were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a glycosylation-insensitive anti-β1 integrin antibody, MAB 2000 (Chemicon International). Protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) were then added, and samples were incubated for 2 additional hours at 4 °C with rotation. The agarose beads were washed with lysis buffer and then boiled in 2× SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer. Precipitated proteins were resolved by on 7% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were exposed to alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated gal-3 and developed with nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (25).

Galectin-3-induced Apoptosis—Cells were seeded in 4-well chamber slides (BD Biosciences) or 6-well plates in complete medium for 24 h. The adherent cells (40-60% confluency) were then washed with PBS twice and incubated in serum-free medium in the presence or absence of gal-3 (R&D Systems) or gal-3 plus β-lactose (Sigma) for 24 h. Direct visualization of the cells following the gal-3 incubation did not reveal any significant increases in the number of detached cells, suggesting that the addition of soluble gal-3 had no effect on cell adhesion to tissue culture plastic. After gal-3 treatment, the cells were either fixed for Hoechst 33258 staining or solubilized in protein lysis buffer for cleaved caspase-3 Western blots. The 24-h time point for analyzing apoptotic responses to gal-3 was selected because this is a common time interval for evaluating apoptosis of epithelial cells and has been used previously to study gal-1- and gal-3-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes. We recognize that soluble gal-3 was used in this assay, rather than the immobilized form of gal-3 used for binding assays. We considered examining apoptosis in response to immobilized gal-3 but concluded that such experiments might be difficult to interpret. Specifically, ST6 cells do not adhere well on immobilized gal-3 (as shown in Fig. 1), and extended incubations would likely result in anoikis. Accordingly, it might be difficult to discriminate between anoikis-related apoptosis versus gal-3-induced apoptosis.

FIGURE 1.

α2-6 sialylation inhibits the attachment of SW48 cells to gal-3 and cell adhesion to gal-3 is dependent upon β1 integrins. Par, EV, or ST6Gal-I-expressing (ST6) SW48 cells were seeded onto cell culture plates coated with either gal-3 or gal-1, and binding was quantified by measuring the fluorescence of calcein AM-labeled cells. BSA- and poly-l-lysine (PL)-coated wells were used as negative and positive controls respectively. A, expression of ST6Gal-I inhibits cell adhesion to gal-3 (* denotes significant difference relative to parental cells on gal-3, p < 0.001). However, none of the cell lines tested adhered to gal-1. B, cell binding to gal-3 is inhibited by 20 mm β-lactose but not 20 mm sucrose, indicating that gal-3 binding is carbohydrate-dependent (* denotes significant difference from parental cells on gal-3; # denotes significant inhibition by β-lactose, p < 0.001). C, Par and ST6 cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-β1 integrin antibody (dotted line) or FITC-conjugated mouse IgG1 (solid line) and analyzed by flow cytometry for cell surface staining of β1 integrins. Par and ST6 cells have similar β1 integrin expression on the cell surface. Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) ± S.D. from three independent experiments are given in each plot. D, parental and ST6 cells were preincubated with either an anti-β1 integrin function blocking antibody or a mouse IgG1 isotype control for 45 min at 37 °C. The cells were subsequently seeded onto gal-3-coated wells, and adhesion was quantified as described previously. As shown, gal-3 binding was significantly inhibited by the anti-β1 integrin function blocking antibody (* denotes significant difference from parental cells; # denotes significant inhibition from ST6 cells, p < 0.001). All values from adhesion experiments represent the means and S.E. for three independent experiments performed with at least three samples per cell line.

To evaluate integrin involvement in gal-3-induced apoptosis, cells were allowed to adhere to tissue culture plates for 24 h as before, and then anti-β1 integrin function-blocking antibodies were added to the cells for 45 min followed by the addition of the gal-3-containing medium. Four different antibodies were tested (at 35 μg/ml): two distinct anti-β1 function-blocking antibodies (catalog numbers MAB1965 and MAB2253, Chemicon International) and two distinct IgG1 isotype controls (Chemicon International, catalog number PP100; and R&D Systems, catalog number MAB002). Neither the anti-β1 nor the control antibodies had any apparent effect on cell attachment or morphology (data not shown).

Hoechst 33258 Staining—Cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS and treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min. The cells were then washed with PBS and stained with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were mounted with Aqua-Poly/Mount medium (Polysciences Inc.), and the percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated from 10 different randomly selected fields at ×40 objective. Apoptotic nuclei were visualized by nuclear condensation and fragmentation. All data were analyzed by a Student's paired t test.

Staurosporine-induced Apoptosis—Cells were seeded in 6-well plates in complete medium for 24 h before treatment. The cells were washed with PBS twice and incubated in 1 μm staurosporine (Cell Signaling Technology) for 4 h. The cells were lysed in protein lysis buffer for cleaved caspase-3 Western blots.

RESULTS

α2-6 Sialylation Inhibits the Binding of SW48 Cells to Galectin-3—Parental (Par), EV-transduced, or ST6Gal-I-expressing (ST6) SW48 cells were evaluated for cell adhesion to either gal-1 or gal-3. Briefly, cells were allowed to adhere for 2 h to tissue culture wells precoated with either gal-1 or gal-3. BSA- and poly-l-lysine-coated wells were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1A, none of the cell lines exhibited any specific binding to gal-1; therefore this lectin was not studied further. In contrast, Par and EV cells demonstrated substantial binding to gal-3, whereas the binding of ST6Gal-I-expressing cells was limited. Cell attachment to gal-3 was significantly inhibited by β-lactose but not by an equivalent concentration of sucrose, indicating that gal-3 binds to specific carbohydrate structures (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these data suggest that α2-6 sialic acids, added by the ST6Gal-I sialyltransferase, block the binding of gal-3 to cell surface glycan targets.

Cell Adhesion to Galectin-3 Is Dependent upon β1 Integrins—The dual findings that β1 integrins can be differentially sialylated (5, 11, 12) and are binding partners for galectins (26) prompted us to test whether gal-3 binding was mediated by the β1 subunit. Of note, Par and ST6 cells express equivalent amounts of cell surface β1 integrins (Fig. 1C); therefore diminished attachment of ST6 cells is not due to a reduction in integrin expression. To assess the role of the β1 integrin in gal-3 binding, cell attachment was evaluated in the presence of anti-β1 integrin function blocking antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1D, anti-β1 blocking antibodies markedly inhibited the binding of parental cells to gal-3, and interestingly, also attenuated the binding of ST6Gal I expressors. These results suggest that β1 integrins play a major role in regulating cell adhesion to this lectin.

Desialylation of ST6 Cells Increases Cell Adhesion to Galectin-3—To verify that α2-6 sialylation inhibits gal-3 binding, cells were treated with neuraminidase to remove sialic acids and then evaluated for binding to gal-3-coated plates. We first tested neuraminidase efficacy by monitoring the electrophoretic mobility of the β1 integrin following neuraminidase treatment. As shown in Fig. 2A, the mature form of the β1 integrin from ST6 cells has a reduced electrophoretic mobility as compared with integrins from Par cells; this altered mobility was previously confirmed to result from increased α2-6 sialylation (12). Neuraminidase treatment of integrins from ST6 cells caused a dose-dependent increase in the electrophoretic mobility of the mature β1 isoform, consistent with the enzymatic removal of sialic acids. In contrast, the electrophoretic mobility of mature β1 integrins from Par cells was not altered by neuraminidase treatment, consistent with the fact that parental SW48 cells do not express either α2-3 or α2-6 sialyltransferases (24). Neuraminidase treatment also had no effect on the mobility of the precursor β1 isoform from either Par or ST6 cells, which was expected given that the precursor is thought to be localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (and is therefore not a substrate for ST6Gal-I).

FIGURE 2.

Treatment with neuraminidase removes α2-6-linked sialic acid of β1 integrins and increases ST6 cell adhesion to gal-3. A, lysates from Par and ST6 cells were treated with varying concentrations of neuraminidase and immunoblotted for the β1 integrin. The blot was then stripped and reprobed for β-actin. Cont, control. B, Par and ST6 cells were treated with 50 units of neuraminidase and washed with PBS. The cells were resuspended in serum-free medium and subsequently seeded onto gal-3-coated wells, and adhesion was quantified as described previously. As shown, the adhesion of ST6 cells to gal-3 was significantly increased by neuraminidase treatment (* denotes significant difference from parental cells; # denotes significant difference between ST6 cells with and without neuraminidase treatment, p < 0.001). PL, poly-l-lysine.

As shown in Fig. 2B, ST6 cells treated with neuraminidase demonstrated a 3-fold increase in gal-3 binding as compared with untreated ST6 cells. In contrast, neuraminidase treatment had no effect on the binding of parental cells to gal-3. Collectively, these results strongly suggest that α2-6 sialylation inhibits the binding of SW48 cells to gal-3.

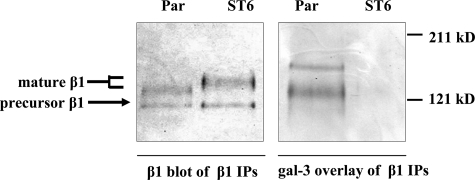

α2-6 Sialylation of β1 Integrins Abolishes Galectin-3 Binding—To determine whether gal-3 binds directly to β1 integrins, we used a gal-3 overlay technique. Briefly, β1 integrins were immunoprecipitated from either parental or ST6Gal-I-expressing cells, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membrane. The membrane was then overlaid with an AP-conjugated gal-3. As shown in Fig. 3, AP-conjugated gal-3 can directly bind to the mature form of β1 integrins immunoprecipitated from parental, but not ST6Gal-I-expressing, cells. These data suggest that α2-6 sialylation of β1 integrins blocks gal-3 binding. Interestingly, a higher molecular weight band was also detected in the gal-3 overlay of β1 immunoprecipitates, suggesting that another gal-3 ligand associates with, and is co-precipitated by, β1. The identity of this glycoprotein is currently unknown. To verify that equal amounts of β1 were precipitated, duplicate immunoprecipitated samples were immunoblotted for β1 (Fig. 3). Notably, gal-3 does not appear to bind to the precursor β1 isoform, which is consistent with the hypothesis that this endoplasmic reticulum-resident β1 isoform is modified with high mannose-type glycans that are not substrates for galectins.

FIGURE 3.

α2-6 sialylation of β1 integrins abolishes gal-3 binding. β1 integrins were immunoprecipitated (IP) from parental or ST6Gal-I-expressing cells, resolved by 7% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membrane. The membrane was overlaid with an AP-conjugated gal-3. As shown, the AP-conjugated gal-3 bound the mature β1 integrin from parental cells but not ST6Gal-I expressors. Duplicate immunoprecipitated samples were immunoblotted with an anti-β1 integrin antibody to verify equivalent levels of β1 in the immunoprecipitates.

α2-6 Sialylation of Cell Surface Proteins Does Not Alter the Expression Level or Subcellular Localization of Endogenous Galectin-3—A number of studies have reported that gal-3 is highly expressed in tumor cells, including colon cancer cells (27); therefore we tested whether SW48 cells produce endogenous gal-3. To evaluate the levels of endogenous gal-3, lysates from parental, EV, and ST6Gal-I-expressing SW48 cells were immunoblotted. Results from these experiments showed that Par, EV, and ST6 cells express similar levels of endogenous gal-3 but no detectable gal-1. Promonocytic U937 cells were included as a positive control for gal-1 (Fig. 4A). In addition to assessing gal-3 protein levels, gal-3 subcellular distribution was monitored by immunofluorescent microscopy. As shown in Fig. 4, B and C, the staining of endogenous gal-3 was mainly cytoplasmic in all three SW48 populations, which is noteworthy in light of studies suggesting that a cytoplasmic localization of gal-3 is pro-tumorigenic (15, 16). Thus, our data suggest that Par, EV, and ST6 cells all produce robust amounts of endogenous, cytoplasmic gal-3, and forced expression of ST6Gal-I does not alter either gal-3 levels or subcellular distribution.

FIGURE 4.

α2-6 sialylation did not change the expression or subcellular localization of gal-3. A, lysates from Par, EV, ST6, and the promonocytic cell line, U937, were Western blotted with antibody against gal-1 and then stripped and reblotted for gal-3 and β-actin. B, immunofluorescent staining of gal-3 in Par, EV, and ST6 cells seeded onto coverslips and allowed to adhere for 3 h at 37°C. C, immunofluorescent staining of Par cells with anti-gal-3 antibody, or alternately, with a control IgG2b or no primary antibody (no Ab) as negative controls. Hoechst 33258 was used for nuclear staining.

ST6Gal-I Protects Cells from Galectin-3-induced Apoptosis—Given our results suggesting that α2-6 sialylation blocks gal-3 binding, we hypothesized that ST6Gal-I expression would attenuate gal-3-induced apoptosis in SW48 cells. To test this hypothesis, Par and ST6 cells were seeded onto chamber slides, treated with different concentrations of human recombinant gal-3 for 24 h, and then evaluated for nuclear morphology. Hoechst 33258 staining was used to detect nuclear condensation and fragmentation. As shown in Fig. 5A, the addition of exogenous gal-3 induced apoptosis in parental cells in a dose-dependent manner, whereas the ST6Gal-I-expressing cells were protected against apoptosis. To confirm that the effects of exogenously added gal-3 were due to the binding of gal-3 to cell surface oligosaccharides, gal-3-induced apoptosis was examined in the presence and absence of β-lactose. These studies showed that β-lactose significantly inhibited gal-3-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5B). To further confirm that α2-6 sialylation inhibits gal-3-mediated apoptosis, we measured levels of activated caspase-3 in the parental, EV, and ST6Gal-I-expressing populations. As shown in Fig. 5C, exogenously added gal-3 stimulated caspase-3 activation (as measured by immunoblotting for the cleaved form of caspase-3) in Par- and EV-transduced cells but not in ST6Gal-I-expressing cells. As well, gal-3-induced caspase-3 activation was blocked by β-lactose, confirming that the apoptotic effects of gal-3 are mediated through gal-3 binding to oligosaccharide determinants.

FIGURE 5.

ST6Gal-I protects cells from gal-3-induced apoptosis. A, Par and ST6 cells were seeded onto chamber slides and treated with different concentrations of human recombinant gal-3 (0, 1, 10, and 20 μg/ml) in serum-free medium for 24 h. The cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst 33258 to detect apoptotic nuclei. The percentage of apoptotic cells was counted from 10 different randomly selected fields at ×40 objective. Values represent means and S.E. for two independent experiments (* denotes significant difference from parental cells, p < 0.001). B, Par, EV, and ST6 cells were incubated in serum-free medium in the presence or absence of 20 μg/ml gal-3 or 20 μg/ml gal-3 + 20 mm β-lactose for 24 h. The percentage of apoptotic cells stained by Hoechst 33258 was counted as above. Values represent means and S.E. for two independent experiments (* denotes significant difference from parental cells, p < 0.001; # denotes significant inhibition by β-lactose, p < 0.001). C, cells were treated as described in panel B and then lysed and Western blotted for cleaved (activated) caspase-3 and β-actin.

Galectin-3-induced Apoptosis Is Dependent upon β1 Integrins—As shown in Figs. 1 and 3, cell adhesion to gal-3 is dependent upon β1 integrins, and gal-3 binds directly to the unsialylated β1 glycoform. Therefore, we questioned whether gal-3-induced apoptosis was mediated by β1 integrins. To test this hypothesis, gal-3 was added to adherent parental cells in the presence or absence of anti-β1 integrin function blocking antibodies. The cells were then lysed and monitored for caspase-3 activation. As shown in Fig. 6A, two distinct anti-β1 integrin blocking antibodies had a markedly inhibitory effect on gal-3-induced caspase activation, whereas control antibodies had a negligible effect.

FIGURE 6.

Galectin-3-induced apoptosis is dependent upon β1 integrins. A, parental cells were preincubated with two distinct function-blocking antibodies against the β1 integrin or with two mouse IgG isotype controls for 45 min at 37 °C. The cells were incubated in serum-free medium in the presence or absence of 20 μg/ml gal-3 for 24 h and then lysed and Western blotted for cleaved caspase-3 and β-actin. B, staurosporine induces apoptosis in both parental and ST6Gal-I-expressing cells. Par and ST6 cells were treated with 1 μm staurosporine for 4 h. The cell lysates were Western blotted for cleaved caspase-3 and β-actin.

To further evaluate whether differential integrin sialylation plays a specific role in regulating gal-3-induced apoptosis, we examined apoptosis in response to staurosporine. Staurosporine targets the mitochondria, and therefore the efficacy of this agent should not be influenced by changes in cell surface sialylation. As shown in Fig. 6B, staurosporine induced equivalent levels of caspase-3 activation in parental and ST6Gal-I expressors, consistent with the hypothesis that cell surface α2-6 sialylation functions as a specific block for gal-3 binding and activity.

DISCUSSION

Numerous reports suggest that α2-6 sialic acid and ST6Gal-I are elevated in multiple types of human tumors, particularly in highly invasive ones (4, 5). However, the mechanisms underlying the role of ST6Gal-I in tumor cell growth and metastasis remain to be elucidated. Here, we provide new insight into how ST6Gal-I overexpression might promote tumor progression. Specifically, we find that α2-6 sialylation of the β1 integrin receptor protects epithelial tumor cells from gal-3-induced apoptosis. An expanding literature supports the idea that extracellular galectins, including gal-3 and gal-1, promote cell apoptosis. However, the vast majority of studies have focused on cells of the immune system. For example, gal-1 is thought to stimulate cell death in T lymphoma cells (28) and human immunodeficiency virus, type 1-infected T cells (29) through binding to core 2 O-linked glycans on the cell surface. In the latter study, gal-1 binding to infected T cells was enhanced upon loss of sialic acid. Likewise, extracellular gal-3 stimulates apoptosis in human leukemia T cell lines (26), human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (26), activated mouse T cells (26), human B cell lymphoma (30), mouse thymocytes (31), mast cells (32), and neutrophils (33). Our studies now indicate that, as with immune cells, gal-3 plays a role in regulating epithelial cell survival.

Our study is also noteworthy because it addresses an apparent paradox. Why would a tumor cell simultaneously up-regulate both gal-3 and ST6Gal-I when ST6Gal-I blocks the binding of gal-3 to the cell surface? We hypothesize that increased levels of intracellular forms of gal-3 (which function largely through carbohydrate-independent mechanisms) promote tumor cell survival, whereas extracellular gal-3 is pro-apoptotic. This concept is supported by a substantial literature. For example, intracellular gal-3 protects cells against apoptotic stimuli including cisplatin, genistein, and nitric oxide (34). Furthermore, the anti-apoptotic activity of intracellular gal-3 is thought to be mediated through direct binding to molecules such as Bcl-2 family members (35), synexin (36), CD95 (37), and activated K-Ras (38). The binding of gal-3 to K-Ras prolongs Ras-induced signaling (39), which is interesting in light of studies showing that Ras activation increases ST6Gal-I expression (11, 40). The subcellular distribution of intracellular gal-3 is also thought to be important. It was reported that overexpression of gal-3 in the cytoplasm increased its anti-apoptotic activity, whereas overexpression of gal-3 in the nucleus decreased its proliferative activity in prostate cancer cells (41). In our study, both parental and ST6Gal-I-expressing SW48 cells expressed high levels of intracellular gal-3 that localized primarily to the cytoplasm, suggesting that this endogenously expressed gal-3 might have anti-apoptotic activity. In contrast to the effects of intracellular gal-3, prior studies of immune cells, coupled with our current results from epithelial cells, suggest that extracellular gal-3 functions largely as an apoptosis inducer. When taken together, these results suggest that up-regulating ST6Gal-I, in conjunction with gal-3 overexpression, would attenuate the pro-apoptotic effects of secreted gal-3, while leaving intact the anti-apoptotic effects of intracellular gal-3, thus providing a selective advantage for the tumor cell.

The up-regulated synthesis of gal-3 in tumor cells results in increases in both intracellular and secreted forms of gal-3, as exemplified by the observation that patients with metastatic disease have higher levels of gal-3 in sera (42). Within the tumor microenvironment, secreted gal-3 is thought to promote angiogenesis and also attenuate anti-tumor immune responses by inducing T cell apoptosis (15). As with gal-3, the synthesis of gal-1 by LNCaP prostate cancer cells caused the death of bound T cells (43). Thus, we hypothesize that the pro-apoptotic functions of galectins secreted from tumor cells will contribute to tumor evasion from the immune system by acting on T cells but will have no effect on tumor cells that have increased cell surface α2-6 sialylation.

The idea that α2-6 sialylation serves as an “on-off switch” for galectin binding and function is supported by studies of both synthetic oligosaccharides (20, 44) and cell surface glycans (21, 22, 30, 45-47). ST6Gal-I selectively modifies N-glycans on CD45 to negatively regulate gal-1-induced T cell death (21). Similarly, TH2 cells, which are resistant to gal-1-induced apoptosis, express higher levels of α2-6 sialylation than TH1 cells (which are gal-1 sensitive), and TH2 gal-1 susceptibility can be restored by the enzymatic removal of α2-6, but not α2-3, sialic acids (46) In accordance with studies of cell surface glycans, Hirabayashi's work indicated that α2-3 sialylation of synthetic β-galactosides was tolerated by some galectins, but none of the galectins studied could bind to α2-6 sialylated β-galactosides (20). A somewhat different finding was reported by de Melo et al. (25). This group did observe some binding of gal-3 to synthetic oligosaccharides with α2-6 sialylated β-galactosides; however, the level of binding was markedly lower than that observed with α2-3 sialylated oligosaccharides. Cummings' group (48) also reported that α2-6 sialylation significantly inhibited the interaction of gal-3 with lactosamine; however the α2-6 sialylation of polylactosamines seemed less effective at blocking gal-3 binding. These investigators hypothesized that gal-3 can bind laterally to the lactosamine units within a polylactosamine chain, thus weakening the inhibitory effect of the terminal sialic acid.

In the current study, we found that expression of ST6Gal-I in colon epithelial cells markedly inhibited cell attachment to gal-3-coated plates, and attachment could be restored by pretreating ST6 cells with neuraminidase. In addition, we used a blot overlay approach to show that gal-3 binds directly and preferentially to unsialylated β1 integrins, as compared with sialylated integrins. Interestingly, ST6Gal-I-expressing cells did retain some binding to gal-3-coated plates, and much of this binding was β1 integrin-dependent. The molecular mechanisms underlying β1-dependent attachment of ST6 cells to gal-3 are not currently understood. It is possible that cells with α2-6 sialylation maintain some level of affinity for gal-3, perhaps through the lateral binding of gal-3 to polylactosamine chains, as suggested by Cummings' group (48). Clearly, additional studies will be needed to elucidate the molecular basis for ST6 cell attachment to immobilized gal-3; nonetheless, our results unequivocally demonstrate a strong inhibitory effect of α2-6-linked sialic acids on cell binding to gal-3, as well as gal-3-directed apoptosis.

Information concerning which cell surface receptors are responsible for transducing galectin-dependent signals is still very limited; however, the literature suggests that there is some specificity in this regard. Suzuki et al. (32) showed that gal-3 binding to RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end products) receptors on mast cells induced oxidative stress, leading to caspase-mediated cell death. Baum's group (49) demonstrated that gal-1 could bind to β1 integrins, CD45, CD71, and CD43 in T cells; however, in this system, CD45 appeared to be the major receptor regulating gal-1-induced apoptosis. In contrast to Baum's study, Fukumori et al. (26) suggested that the β1 integrin was the crucial receptor for gal-3-mediated T cell apoptosis. The β1 family of integrins appears to be a particularly prevalent ligand for galectins, as evidenced by the multiple galectin/integrin associations that have been reported: for example, gal-1 binding to α7β1, gal-3 binding to α1β1, and gal-8 binding to either α3β1 or α6β1 (15). Our results suggest that the β1 integrin is one of the predominant receptors mediating colon epithelial cell association with, and apoptotic responses induced by, extracellular gal-3. Importantly, we show that sialylation of β1 by ST6Gal-I blocks the pro-apoptotic effects of extracellular gal-3. Thus, differential sialylation of β1 integrins not only modulates cell responses to traditional extracellular matrix proteins like collagen and fibronectin, as we have previously reported (11, 12, 50, 51), but also serves as a potential mechanism for regulating cell interactions with matrix-tethered galectins. In the aggregate, these studies suggest that variant integrin glycoforms play a multifactorial role in regulating tumor cell interaction with matrix. Importantly, the expression of hypersialylated integrin glycoforms occurs in response to biologically relevant events, such as oncogenic Ras-induced cell transformation (11). Moreover α2-6 sialylation of β1 integrins is elevated in human colon tumors, as compared with pair-matched controls (12).

Interestingly, anti-β1 integrin function blocking antibodies did not eliminate all of the cell adhesion to gal-3, suggesting that other molecular interactions may be important. In accordance with these results, the gal-3 overlay experiments (Fig. 3) revealed that another galectin-binding protein was present in β1 integrin immunoprecipitates; the identity of this glycoprotein is currently unknown. Several other cell-associated ligands for gal-3 have been reported, including the epidermal growth factor receptor (52), transforming growth factor-β receptor (52, 53), T cell receptor (53), Mac-2-binding protein (54), RAGE (32), Lamp-1,2, and carcinoembryonic antigen (55). Interestingly, carcinoembryonic antigen is highly expressed in colon cancer cells, and like the β1 integrin, is known to be hypersialylated with α2-6 sialic acid (56). Additional experiments will be needed to identify other galectin-binding proteins and also to dissect the specific galectin-dependent functions of these respective molecules.

In sum, the important finding of this study is that α2-6 sialylation of the β1 integrin attenuates gal-3-induced epithelial cell apoptosis, which in turn offers a molecular explanation for why the simultaneous up-regulation of ST6Gal-I and gal-3 in tumor cells might provide a selective advantage. Finally, our results have translational implications in that recombinant galectins are currently being considered for use in cancer treatment (57). It is highly likely that such a strategy would be less effective with cancers (e.g. colon carcinoma), which typically express high levels of α2-6 sialylation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fabiana H. M. de Melo from Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Saãc;o Paulo, Saãc;o Paulo, Brazil for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01CA84248 (to S. L. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ST6Gal-I, β-galactosamide α-2,6-sialyltranferase I; AP, alkaline phosphatase; gal, galectin; Par, parental; EV, empty vector; BSA, bovine serum albumin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PVDF, polyvinylidene difluoride.

References

- 1.Hakomori, S. (1996) Cancer Res. 56 5309-5318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorelik, E., Galili, U., and Raz, A. (2001) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 20 245-277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis, J. W. (1991) Semin. Cancer Biol. 2 411-420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dall'Olio, F. (2000) Glycoconj. J. 17 669-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellis, S. L. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1663 52-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chammas, R., McCaffery, J. M., Klein, A., Ito, Y., Saucan, L., Palade, G., Farquhar, M. G., and Varki, A. (1996) Mol. Biol. Cell 7 1691-1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bresalier, R. S., Rockwell, R. W., Dahiya, R., Duh, Q. Y., and Kim, Y. S. (1990) Cancer Res. 50 1299-1307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Marer, N., and Stehelin, D. (1995) Glycobiology 5 219-226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin, S., Kemmner, W., Grigull, S., and Schlag, P. M. (2002) Exp. Cell Res. 276 101-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu, Y., Srivatana, U., Ullah, A., Gagneja, H., Berenson, C. S., and Lance, P. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1536 148-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seales, E. C., Jurado, G. A., Singhal, A., and Bellis, S. L. (2003) Oncogene 22 7137-7145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seales, E. C., Jurado, G. A., Brunson, B. A., Wakefield, J. K., Frost, A. R., and Bellis, S. L. (2005) Cancer Res. 65 4645-4652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elola, M. T., Wolfenstein-Todel, C., Troncoso, M. F., Vasta, G. R., and Rabinovich, G. A. (2007) CMLS Cell Mol. Life Sci. 64 1679-1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochieng, J., Furtak, V., and Lukyanov, P. (2004) Glycoconj. J. 19 527-535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu, F. T., and Rabinovich, G. A. (2005) Nat. Rev. Cancer 5 29-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumic, J., Dabelic, S., and Flogel, M. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1760 616-635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes, R. C. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1473 172-185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakahara, S., Oka, N., and Raz, A. (2005) Apoptosis 10 267-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bresalier, R. S., Mazurek, N., Sternberg, L. R., Byrd, J. C., Yunker, C. K., Nangia-Makker, P., and Raz, A. (1998) Gastroenterology 115 287-296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirabayashi, J., Hashidate, T., Arata, Y., Nishi, N., Nakamura, T., Hirashima, M., Urashima, T., Oka, T., Futai, M., Muller, W. E., Yagi, F., and Kasai, K. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1572 232-254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amano, M., Galvan, M., He, J., and Baum, L. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 7469-7475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki, O., Nozawa, Y., and Abe, M. (2006) Int. J. Oncol. 28 155-160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hay, R., Caputo, J., Chen, T. R., Macy, M., McClintock, P., and Reid, Y. (1994) ATCC Cell Lines and Hybridomas, 8th Ed., ATCC, Rockville, MD

- 24.Dall'Olio, F., Chiricolo, M., Lollini, P., and Lau, J. T. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 211 554-561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Melo, F. H., Butera, D., Medeiros, R. S., Andrade, L. N., Nonogaki, S., Soares, F. A., Alvarez, R. A., Moura da Silva, A. M., and Chammas, R. (2007) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 55 1015-1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukumori, T., Takenaka, Y., Yoshii, T., Kim, H. R., Hogan, V., Inohara, H., Kagawa, S., and Raz, A. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 8302-8311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lahm, H., Andre, S., Hoeflich, A., Kaltner, H., Siebert, H. C., Sordat, B., von der Lieth, C. W., Wolf, E., and Gabius, H. J. (2004) Glycoconj. J. 20 227-238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabrera, P. V., Amano, M., Mitoma, J., Chan, J., Said, J., Fukuda, M., and Baum, L. G. (2006) Blood 108 2399-2406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanteri, M., Giordanengo, V., Hiraoka, N., Fuzibet, J. G., Auberger, P., Fukuda, M., Baum, L. G., and Lefebvre, J. C. (2003) Glycobiology 13 909-918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki, O., and Abe, M. (2008) Oncol. Rep. 19 743-748 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silva-Monteiro, E., Reis Lorenzato, L., Kenji Nihei, O., Junqueira, M., Rabinovich, G. A., Hsu, D. K., Liu, F. T., Savino, W., Chammas, R., and Villa-Verde, D. M. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 170 546-556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki, Y., Inoue, T., Yoshimaru, T., and Ra, C. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783 924-934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez, G. C., Ilarregui, J. M., Rubel, C. J., Toscano, M. A., Gomez, S. A., Beigier Bompadre, M., Isturiz, M. A., Rabinovich, G. A., and Palermo, M. S. (2005) Glycobiology 15 519-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang, R. Y., Hsu, D. K., and Liu, F. T. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93 6737-6742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akahani, S., Nangia-Makker, P., Inohara, H., Kim, H. R., and Raz, A. (1997) Cancer Res. 57 5272-5276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu, F., Finley, R. L., Jr., Raz, A., and Kim, H. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 15819-15827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukumori, T., Takenaka, Y., Oka, N., Yoshii, T., Hogan, V., Inohara, H., Kanayama, H. O., Kim, H. R., and Raz, A. (2004) Cancer Res. 64 3376-3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elad-Sfadia, G., Haklai, R., Balan, E., and Kloog, Y. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 34922-34930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashery, U., Yizhar, O., Rotblat, B., Elad-Sfadia, G., Barkan, B., Haklai, R., and Kloog, Y. (2006) Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 26 471-495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalziel, M., Dall'Olio, F., Mungul, A., Piller, V., and Piller, F. (2004) Eur. J. Biochem. 271 3623-3634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Califice, S., Castronovo, V., Bracke, M., and van den Brule, F. (2004) Oncogene 23 7527-7536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iurisci, I., Tinari, N., Natoli, C., Angelucci, D., Cianchetti, E., and Iacobelli, S. (2000) Clin. Cancer Res. 6 1389-1393 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valenzuela, H. F., Pace, K. E., Cabrera, P. V., White, R., Porvari, K., Kaija, H., Vihko, P., and Baum, L. G. (2007) Cancer Res. 67 6155-6162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leppanen, A., Stowell, S., Blixt, O., and Cummings, R. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 5549-5562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holikova, Z., Hrdlickova-Cela, E., Plzak, J., Smetana, K., Jr., Betka, J., Dvorankova, B., Esner, M., Wasano, K., Andre, S., Kaltner, H., Motlik, J., Hercogova, J., Kodet, R., and Gabius, H. J. (2002) APMIS 110 845-856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toscano, M. A., Bianco, G. A., Ilarregui, J. M., Croci, D. O., Correale, J., Hernandez, J. D., Zwirner, N. W., Poirier, F., Riley, E. M., Baum, L. G., and Rabinovich, G. A. (2007) Nat. Immunol. 8 825-834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andre, S., Sanchez-Ruderisch, H., Nakagawa, H., Buchholz, M., Kopitz, J., Forberich, P., Kemmner, W., Bock, C., Deguchi, K., Detjen, K. M., Wiedenmann, B., von Knebel Doeberitz, M., Gress, T. M., Nishimura, S., Rosewicz, S., and Gabius, H. J. (2007) FEBS J. 274 3233-3256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stowell, S. R., Arthur, C. M., Mehta, P., Slanina, K. A., Blixt, O., Leffler, H., Smith, D. F., and Cummings, R. D. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 10109-10123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stillman, B. N., Hsu, D. K., Pang, M., Brewer, C. F., Johnson, P., Liu, F. T., and Baum, L. G. (2006) J. Immunol. 176 778-789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Semel, A. C., Seales, E. C., Singhal, A., Eklund, E. A., Colley, K. J., and Bellis, S. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 32830-32836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seales, E. C., Shaikh, F. M., Woodard-Grice, A. V., Aggarwal, P., McBrayer, A. C., Hennessy, K. M., and Bellis, S. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 37610-37615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Partridge, E. A., Le Roy, C., Di Guglielmo, G. M., Pawling, J., Cheung, P., Granovsky, M., Nabi, I. R., Wrana, J. L., and Dennis, J. W. (2004) Science 306 120-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demetriou, M., Granovsky, M., Quaggin, S., and Dennis, J. W. (2001) Nature 409 733-739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenberg, I., Cherayil, B. J., Isselbacher, K. J., and Pillai, S. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 18731-18736 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohannesian, D. W., Lotan, D., Thomas, P., Jessup, J. M., Fukuda, M., Gabius, H. J., and Lotan, R. (1995) Cancer Res. 55 2191-2199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kannicht, C., Lucka, L., Nuck, R., Reutter, W., and Gohlke, M. (1999) Glycobiology 9 897-906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bremer, E., van Dam, G., Kroesen, B. J., de Leij, L., and Helfrich, W. (2006) Trends Mol. Med. 12 382-393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]