Abstract

Disulfide nitroxide biradicals, DNB, have been used for glutathione, GSH, measurements by X-band electron paramagnetic resonance, EPR, in various cells and tissues. In the present paper, the postulated potential use of DNB for EPR detection of GSH in vivo was explored. Isotopic substitution in the structure of the DNB was performed for the enhancement of its EPR spectral properties. 15N substitution in the NO fragment of the DNB decreased the number of EPR spectral lines and resulted in an approximately two-fold increase in the signal-to-noise ratio, SNR. An additional two-fold increase in the SNR was achieved by substitution of the hydrogen atoms with deuterium resulting in narrowing the EPR lines from 1.35 G to 0.95 G. The spectral changes of DNB upon reaction with GSH and cysteine were studied in vitro in a wide range of pHs at room temperature and “body” temperature, 37 °C, and the corresponding bimolecular rate constants were calculated. In in vivo experiments the kinetics of the L-band EPR spectral changes after injection of DNB into ovarian xenograft tumors grown in nude mice were measured by L-band EPR spectroscopy, and analyzed in terms of the two main contributing reactions, splitting of the disulfide bond and reduction of the NO fragment. The initial exponential increase of the “monoradical” peak intensity has been used for the calculation of the GSH concentration using the value of the observed rate constant for the reaction of DNB with GSH, kobs (pH 7.1, 37 oC) = 2.6 M-1 s-1. The concentrations of GSH in cisplatin-resistant and cisplatin-sensitive tumors were found to be 3.3 mM and 1.8 mM, respectively, in quantitative agreement with the in vitro data.

Keywords: disulfide biradical nitroxide, thiol-disulfide exchange, in vivo EPR, glutathione, thiols, ovarian cancer

Introduction

Thiol redox state is an important biochemical parameter associated with all major biological processes [1–3]. Redox equilibrium between thiols and disulphides is integrally involved in many processes such as cell signaling and enzymatic mechanisms. The redox state of the glutathione (GSH)/glutathione disulfide (GSSG) couple is considered the major intracellular redox buffer and redox regulator [4]. Low GSH, high GSSG, and a lower GSH/GSSG ratio have been found in various oxidative stress and free radical pathologies [2, 5–7]. Therefore, glutathione redox status in vivo might be a useful indicator of disease risk in humans.

Methods to measure glutathione in vivo could be extremely valuable. Fluorometric, photometric and chromatographic assays for glutathione measurement [6–12] are mostly limited to in vitro or ex vivo detection of thiols, due to the invasiveness required and/or insufficient light penetration into tissue. NMR detection of endogenous GSH has low sensitivity and lacks specificity due to overlapping of numerous resonances [13–15]. A recently developed fluorinated exogenous label for 19F NMR detection of thiols [16] will be difficult to use in vivo due to both low sensitivity and complex spectra analysis.

EPR remains a potential application for in vivo detection and has an advantage over NMR possessing more than three orders of magnitude higher intrinsic sensitivity to the probe concentration. The recent development of low-field EPR techniques makes feasible EPR measurements in isolated organs and living small animals. In our previous work we applied disulfide nitroxide biradicals, DNB, as paramagnetic analogs of Ellman’s reagent, for thiol detection in vitro [17, 18] and postulated potential of their use in vivo [19, 20]. The measurement of thiols in vivo using DNB appears likely to be productive, but requires optimization of the probe, its delivery in living tissue, and experimental justification of the ability to extract quantitative information about thiol content from the EPR spectra measurements. In the present work isotopic 15N and 2H-substitution in the structure of the DNB was performed for the enhancement of its EPR spectral properties. The spectral changes of the DNB upon reactions with the biologically relevant reducing agent, ascorbate, and low-molecular weight thiols were studied in vitro in a wide range of pHs at room temperature and at 37 °C. This provided a basis for the quantitative analysis of the L-band EPR spectra kinetics measured in vivo after injection of the DNB in ovarian xenograft tumors grown in nude mice. The GSH concentrations obtained from the in vivo EPR measurements were found to be in quantitative agreement with in vitro measurements in corresponding tissue homogenates.

Material and Methods

Reagents

Glutathione (GSH) and cysteine (CysSH) were purchased from Sigma

Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), sodium pyrophosphate decahydrate and ascorbic acid were purchased from Acros Organics. Mono- and dibasic sodium phosphate salts were obtained from Fisher Scientific. Cell culture medium (RPMI medium 1640), fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics, sodium pyruvate, trypsin, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from GIBCO/BRL. The DNB label, (see Scheme 1) was synthesized as previously described [18]. The synthesis of 15N and 2H- isotopic substituted DNB labels, and (Scheme 1), is described in the Appendix.

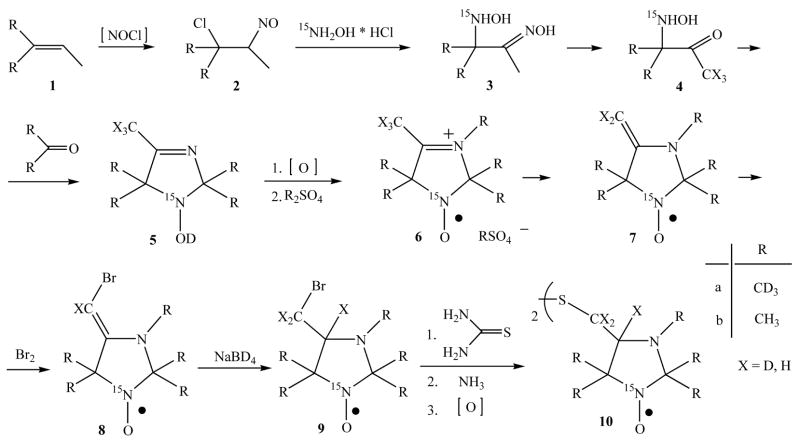

Scheme 1.

The structures of the DNB labels, (i =1, 2, 3).

EPR studies of the reaction of with GSH and CysSH

Studies of the thiol-disulfide exchange kinetics between and low-weight thiols were performed in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, 1 mM DTPA, for pH range from 6 to 8, at temperature 23°C and 37°C; and in 0.1 Na-pyrophosphate buffer, 1 mM DTPA, for pH range from 8 to 12, at 23°C. Disulfide label (10 μM) was mixed with GSH or CysSH at various concentrations and increase of the low-field “monoradical” peak intensity of the EPR spectrum was monitored using X-band EPR spectrometer (EMX, Bruker). Observed rate constants, kobs, of the thiol-disulfide exchange (see reaction 1) were calculated and plotted versus pH values.

EPR studies of the reduction of by ascorbate

(100 μM) was mixed with ascorbic acid (0.625, 1.25, 2.5 and 5 mM) in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTPA, at 23°C, and kinetics of the changes in “monoradical” amplitude of the EPR spectrum was monitored using X-band EPR spectrometer (EMX, Bruker).

EPR studies of reduction of the -derived mononitroxides by ascorbate

Disulfide (0.5 mM) was mixed with 1.5 mM GSH in the presence of 10 mM NaOH

Completion of the thiol-disulfide exchange reaction resulted in the formation of the mononitroxides, and , monitored by EPR. The solution was diluted by 10 times in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 1 mM DTPA, and various concentrations of ascorbic acid (2.5, 5, and 10 mM) were added. The kinetics of the reduction of the and mixture after ascorbic acid addition was monitored using X-band EPR spectrometer (EMX, Bruker). The measured kinetics of the decrease in the low-field component of the mononitroxides EPR spectra was fitted by the monoexponent yielding the value of the observed rate constant, kobs. Bimolecular rate constant of the mononitroxides reduction by ascorbic acid was derived from the linear regression slope of the dependence of kobs on ascorbic acid concentration.

Human ovarian cancer cell lines

Cisplatin-sensitive (A2780 WT) and cisplatin-resistant (A2780 cDDP) human ovarian cancer cell lines were used. The cisplatin-resistant cell line was originally developed from an in vivo tumor model by treating with cisplatin [21]. Cells were grown in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2% sodium pyruvate, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cell culture was carried out at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2. Cells were routinely trypsinized (0.05% trypsin/EDTA) and counted using an automated counter (NucleoCounter, New Brunswick Scientific Co., Edison, NJ).

Animal model of ovarian cancer

Six-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute. The animals were housed five per cage in a climate- and light-controlled room. Food and water were allowed ad libitum. All animals were used according to the Public Health Services Policy, the Federal Welfare Act, and ILACUC procedures and guidelines of The Ohio State University. Cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant human ovarian cancer cells (5×106 cells in 60 μl PBS) were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the upper portion of the right hind limb of mice. Both types of cells grew, in vivo, as a solid tumor. The size of the tumor was measured using a Vernier caliper. Mice with tumor size approximately 8–10 mm in the greater diameter, reached on the 12th–14th day after inoculation, were used for in vivo EPR measurements.

In vivo EPR measurement

The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with ketamine (200 mg/kg b.w.) and xylazine (4 mg/kg b.w.) and inhaled room air (21% O2) during the in vivo measurement. The body temperature of the animal was maintained at 37±1°C by an infrared lamp placed just above the animal during the measurements. The mice were intratumorally (i.t.) injected with 15 μL of 50 mM thiol-sensitive probe, . Note that easily diffuses throughout tumor tissue after i.t. injection [48] resulting in submillimolar probe concentration. This fulfills the requirement [ ]≪[GSH] making this approach less invasive and allowing for the pseudo-first order approximation of the in vivo kinetics. EPR measurements were taken immediately and about every 1 min thereafter for a total of approximately 30 min. The measurements were performed using a home-built L-band (1.2 GHz) EPR spectrometer with a bridged loop-gap resonator [22]. The following parameters were used for L-band EPR spectroscopy: sweep width, 12 G; sweep time, 2.6 s; modulation amplitude, 1 G; time constant, 0.04 s; microwave power, 5 mW. Two groups of animals were investigated: (i) A2780 WT and (ii) A2780 cDDP tumor-bearing mice. At the end of experiment tumor tissues were resected and stored at −80ºC until ex vivo glutathione measurement.

Ex vivo analysis of GSH content in tumor tissue

Tumor tissues (30 mg) were homogenized in 0.5 ml ice cold 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.1, 1 mM DTPA, and 1μl Triton X-100, followed with 13,000 g centrifugation at 4 °C. Supernatants were used for low-weight thiols concentration measurement in tissue. Disulfide (50 μM) was mixed with homogenate in the presence of 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer pH 7.1, 1 mM DTPA, and kinetics of low-field “monoradical” component increase was recorded using X-band EPR spectrometer (EMX, Bruker). The kinetics was fit by linear regression and line slope was calculated. The average rate of “monoradical” component increasing for whole (not diluted) homogenate was calculated using three experiments with varying homogenate concentrations. The concentration of GSH in tumor tissues (in mmole/kg) was calculated using values of rates of “monoradical” component increase in the presence of a known concentration of GSH measured in the same conditions (0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.1, 1 mM DTPA).

Statistical analysis of ex vivo and in vivo studies

Comparisons among groups were performed using a One-Way ANOVA test. The significance level was set at p <0.05.

Results

EPR spectral properties of the disulfide probes

The structures of the previously reported DNB label, [18], and newly synthesized isotopically substituted analogs, and , are shown in the Scheme 1. The EPR spectrum of the biradical is significantly affected by pairwise spin exchange between two radical subunits resulting in appearance of “biradical” components in addition to triplet pattern typical for mononitroxides [23–25] (Fig. 1a). The number and shape of the biradical components is determined by the contribution of several effective conformations of the label with the intermediate character of spin exchange (averaged exchange integral J~aN) [17, 26].

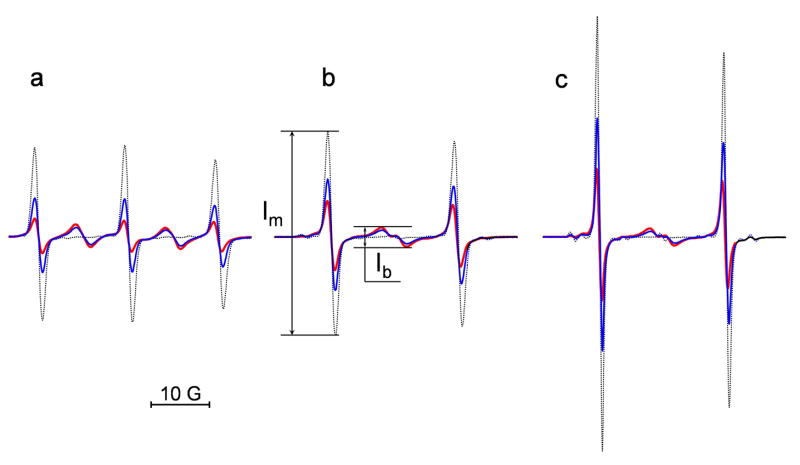

Fig. 1.

The EPR spectra of the DNB label (a) and its isotopically substituted analogues, (b) and (c). The spectra were obtained for 0.1 mM solution of the biradicals alone (red) and after the reaction with different concentrations of GSH added at pH 11.5 (0.1 mM, blue, and 1 mM, black). The spectrometer settings were as following: modulation amplitude, 0.5 G; sweep width, 50 G; microwave power, 10 mW. The maximal increase of the intensity of the “monoradical” component after complete splitting of the disulfide bond, , was equal to (a) 4.6, (b) 3.0 and (c) 3.3. Note that double integration of the EPR spectra shows conservation of the integral spectral intensity during the observed spectral changes.

15N substitution in the NO fragment of the biradicals and decreases the number of EPR spectral lines transforming a triplet pattern to a doublet with additional “biradical” components localized in the center of the spectrum (Fig. 1b and 1c). As a consequence, there is about an observed two times increase in the signal-to-noise ratio, SNR, for the EPR spectra of the compared with . An additional two times increase in the SNR was achieved for the EPR signal of the biradical synthesized by the isotopic substitution of all 34 hydrogen atoms of the by deuterium. The latter enhancement resulted from narrowing EPR lines, namely from 1.35 G to 0.95 G for the peak-to-peak linewidths of the low-field components of and , respectively. This will be particularly important for applications in vivo where fundamental sensitivity is much lower.

Reaction of the disulfide probes with low-molecular-weight thiols

Isotopic substitutions had no effect on the stability of the disulfide bond of the biradicals and their reactivity towards thiols. Aqueous solutions of the biradicals were extremely stable in the broad range of pHs for at least days. An addition of glutathione, GSH, resulted in an increase of the intensity of “monoradical” components and decrease of “biradical” components as shown in Fig. 1. The observed spectral changes are in agreement with the splitting of the disulfide bond and the formation of two monoradicals, and according to eq. (1):

| (1) |

The EPR spectra of the monoradicals and are characteristic of mobile fast rotating low-molecular weight nitroxides and were indistinguishable at X-band or lower frequency EPR spectroscopy (see Fig. 1).

The rates of the reaction (1) of the imidazolidine nitroxides with the thiols vary with pH and temperature. The reaction proceeded within a few seconds at alkaline pH (Fig. 1) and within a few tens of minutes at neutral pH as shown in Figure 2.

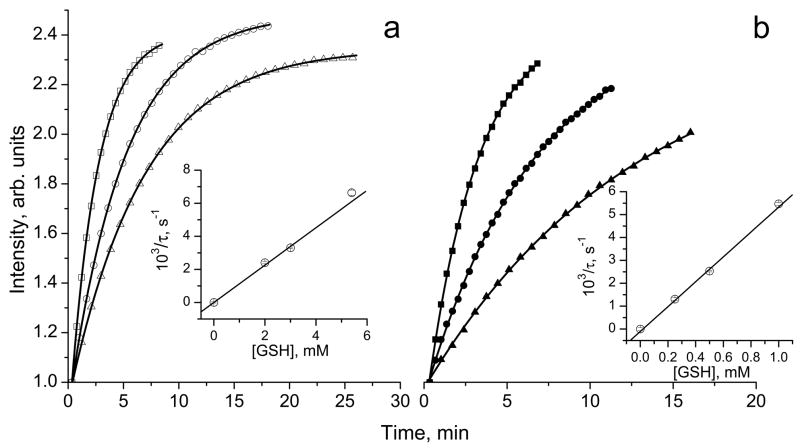

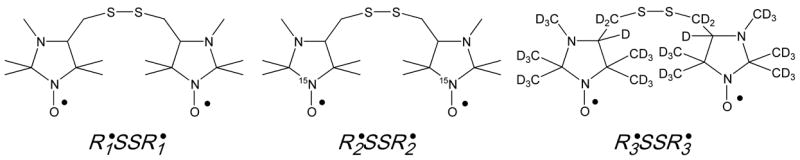

Fig. 2.

The kinetics of the increase of amplitude of the monoradical component, Im, of the EPR spectrum of 10 μM solution in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTPA, measured at (a) 23°C and (b) 37°C after addition of various concentrations of GSH: (△) 2 mM, (○) 3 mM, (□) 5.4 mM and (▲) 0.25 mM, (●) 0.5 mM and (■) 1 mM. Lines represent the best fit of the experimental kinetics to the monoexponents, , yielding the values of the characteristic time constant of the exponential growth, τ. Inserts: the dependences of inverse characteristic time constant of the exponential kinetics, 1/τ, on GSH concentration at (a) 23°C and (b) 37°C. The linear regression provides the values of the observed rate constant of the reaction of thiol-disulfide exchange between GSH and (1/τ = kobs×[GSH]) at pH 7.4 yielding kobs(pH 7.4, 23 °C) = 1.13±0.01 M−1 s−1 and kobs(pH 7.4, 37 °C) = 5.4±0.1 M−1 s−1.

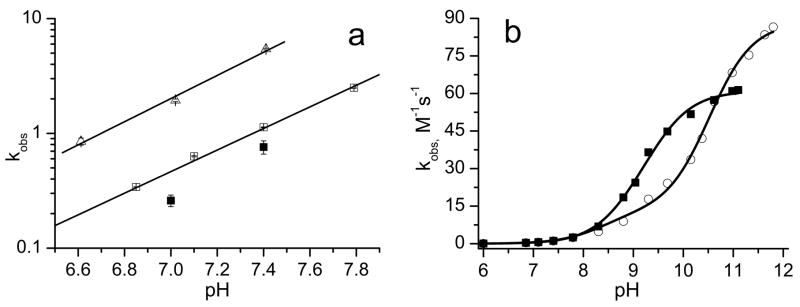

Figure 2 represents the kinetics of the EPR peak intensity increase of the monoradical component, Im, after addition of GSH measured at room temperature, 23°C, and “body” temperature, 37°C. The kinetics show exponential growth with the characteristic time constant, τ = 1/(kobs×[GSH]). Therefore, linear regression of the inverse characteristic time constant, 1/τ, on GSH concentration provides the value of the observed rate constant of the reaction of with GSH, kobs. According to the data shown in Fig. 2, the value of kobs is almost five times larger at the higher temperature. The strong increase of kobs at more alkaline pH was observed for both temperatures (see Fig. 3a) supporting the predominant contribution of the thiolate anion, GS−, in reaction (1). Figure 3b shows pH dependences of kobs for reaction (1) with low-molecular-weight thiols, glutathione and cysteine, CysSH. The detailed description of the rate constant’s pH dependence of the reaction of the biradicals with GSH and CysSH requires consideration of the contribution of different ionization states of both –SH and –NH2 groups of these molecules. Fitting the data to a standard titration equation shows good agreement between experimental and calculated values (see Fig. 3b) yielding significant bimolecular rate constants for only thiolate anions, namely , , and .

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3a. The pH dependences of observed rate constant, kobs, of the reaction of the biradical with GSH plotted in logarithmic scale. The data were obtained from measurements performed at 37°C (△) and 23°C (□); filled squares (■) are the data reported for the at 20°C [18]. Solid lines are linear regressions, log (kobs) = a×pH – b, where a = 0.91±0.05 and b = 6.70±0.1 for 23°C and a = 1.01±0.05 and b = 6.75±0.05 for 37°C.

Fig. 3b. The pH dependences of kobs of the reaction of the biradical with glutathione (■) and cysteine (○) measured at 23°C. Solid curves represent the best fits of the experimental data to titration equation, kobs = (k+k1/[H+]+k0k1k3/[H+]2)/(1+k1/[H+]+k2/[H+]+k1k3/[H+]2) where k+ and k0 are the bimolecular rate constants of thiol-disulfide exchange of the biradical with thiolate anions, GS− or CysS−, with protonated and nonprotonated NH2 group, respectively; K1 and K2 are microscopic ionization constants of SH group of the molecules with protonated and nonprotonated NH2 group, respectively; K3 is a microscopic ionization constant of amino group of the thiolate anion. The fitting was performed using previously reported microscopic ionization constants, pK1 = 8.53, pK2 = 8.86, and pK3= 10.36 for cysteine [27] and pK1 = 8.93, pK2 = 9.13, and pK3= 9.28 for glutathione [28], yielding the following values for the rate constants, and .

Chemical reduction of the disulfide probes

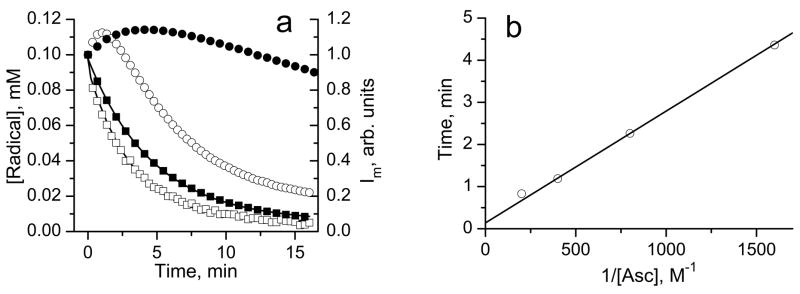

The reactions of the biradicals with GSH and cysteine proceeded with conservation of integral EPR spectral intensity [17, 18] (see Fig. 1). This is in agreement with the previously reported chemical stability of di-tert-alkylnitroxides in the presence of thiols [29, 30]. In general, reduction of the biradicals may interfere with their reaction with thiols adding complexity to EPR detection of thiols. Figure 4a shows the kinetics of the reduction of the biradical and corresponding monoradicals formed after splitting of the disulfide bond (see Figure caption for the details) by access of ascorbate measured by EPR. The integral intensities of the EPR spectra of both the biradical and the monoradicals decayed exponentially with similar rate constants with the reduction, kr, equal to (1.7 ±0.2) M−1 s−1 and (1.5±0.2) M−1 s−1, respectively. However, the peak intensity change of the “monoradical” component is represented by bell-shaped kinetics (Fig. 4a). This kinetic behavior is well described analytically supposing contribution of the two radical forms in the EPR spectrum, namely biradical and half reduced monoradical, both of which undergo one-electron reduction by ascorbate with equal rate constants, kr:

| (2) |

where c1 and c2 are numerical coefficients, [Asc] is the ascorbate anion concentration and t is time after initiation of the reaction. The dependence described by eq. (2) has a maximum, , equal to at time point tmax = (c2 − c1)/c2kr[Asc]. In agreement with the experimental data the value of Imax does not depend on the concentration of ascorbate ( , see Fig. 4a) yielding c2/c1 ≈ 1.7. Note that a maximal increase in “monoradical” peak intensity upon disulfide splitting of the in the absence of reduction, (see Fig. 1), should be equal to 2· c2/c1 due to the formation of two monoradicals from each molecule of the biradical, therefore providing an alternative estimate of c2/c1 ≈ 1.5 which is comparable to 1.7 obtained upon reduction. Experimental dependence of tmax on inverse ascorbate concentration allows for a good linear regression yielding the value of kr equal to (2.2±0.2) M−1 s−1 in reasonable agreement with the kr value for the biradical obtained from the decay of integral intensity of its EPR spectrum (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4a. The kinetics of integral intensities decay of the EPR spectra of 50 μM biradical (□), concentration is multiplied by factor 2 to account for two monoradical subunits) and 100 μM monoradicals, and (■), solutions in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTPA, after addition of 2.5 mM ascorbic acid. The solution of the monoradicals was obtained by mixing 0.5 mM of with 1.5 mM of GSH in 10 mM aqueous NaOH and incubating for about 10 min to complete the biradical disulfide splitting monitored by EPR, then a 10 μl aliquot was diluted in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTPA, and ascorbate was added to initiate the kinetics. Lines are the best exponential fits yielding the bimolecular rate constants for reduction of the biradical, (1.7±0.2) M−1 s−1, and monoradicals, (1.5±0.2) M−1 s−1. The bell-shaped curves represent the kinetics of the low-field EPR peak intensity, Im, of the solution of the biradical in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTPA, after addition of (○) 2.5 mM and (●) 0.625 mM ascorbic acid.

Fig 4b. The dependence of the time point, tmax, corresponding to the maximum of the bell-shaped kinetics of the low-field EPR peak intensity of the solution of the biradical in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTPA, on the inverse concentration of reducing agent, ascorbate. The linear regression yields the value of kr equal to (2.2±0.2) M−1 s−1.

In vivo GSH measurements using the disulfide probes

Typical kinetics of the Im changes after intratumoral injection of in the mice is shown in Figure 5. The observed maximal increase of the peak intensity, Im, exceeds the corresponding number in the case of reduction (see Fig. 4a) by one order of magnitude or more, therefore, justifying negligible contribution of the reduction to the initial part of the kinetics. Fitting the kinetics by the monoexponent, which is characteristic for the reaction with GSH, yields the value of the intracellular GSH concentration (see Fig. 5). The dominant contribution of the intracellular GSH in the observed in vivo kinetics is justified by fast diffusion of the DNB probes across cellular membranes due to their high lipophilicity (octanol/water coefficient is about 240 [18]), highest concentration of the GSH among intracellular thiols, and slow reaction of the probes with protein —SH groups [18]. This conclusion is supported by the similarity of the EPR kinetics measured in vitro in the supernatant obtained from the tissue homogenates before and after protein precipitation (data not shown).

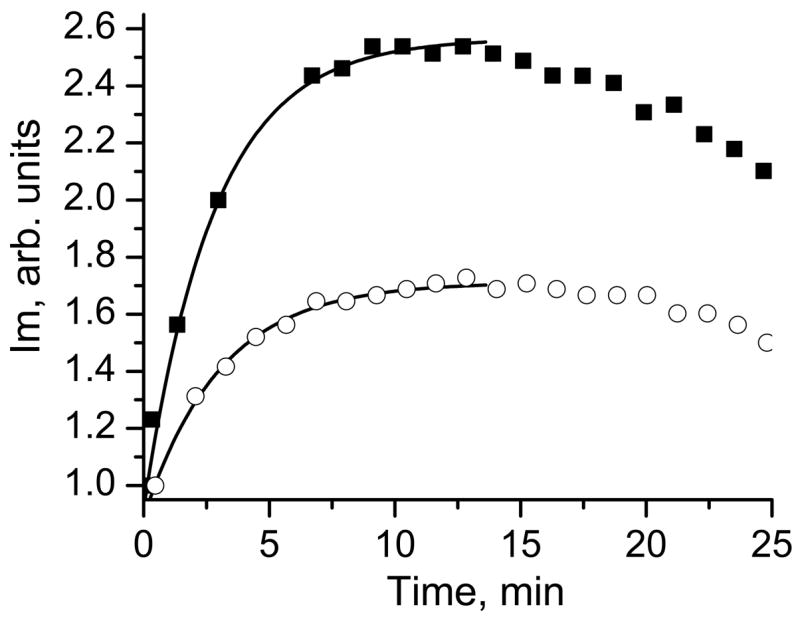

Fig. 5.

The kinetics of the Im peak intensity change measured in vivo in ovarian tumor-bearing mice located directly in the resonator of L-band EPR spectrometer. The representative kinetics observed in the cisplatin-resistant (A2780 cDDP, ■) and cisplatin-sensitive (A2780 WT, ○) ovarian tumors are shown. Lines are the fit of the initial part of the kinetic curve by the monoexponent supposing kobs(pH 7.1, 37 °C) = 2.6 M−1 s−1 and yielding [GSH]r = 3.3 mM and [GSH]s = 1.8 mM for the cisplatin-resistant and cisplatin-sensitive ovarian tumors, respectively.

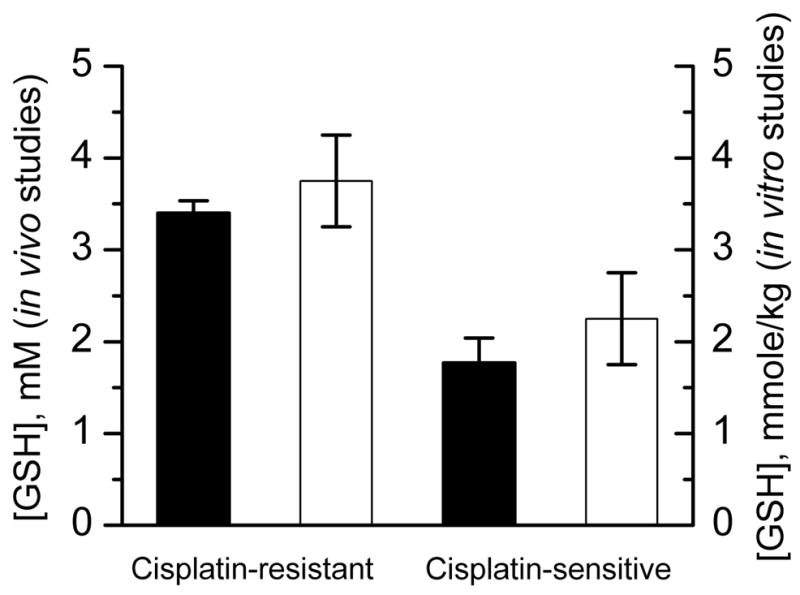

Figure 6 summarizes the results of in vivo and ex vivo measurements of GSH in the cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant ovarian tumors. The GSH concentrations obtained by both approaches are in a good agreement between each other and with previously reported data [31, 32].

Fig. 6.

GSH concentration measured in cisplatin-sensitive and cisplatin-resistant ovarian tumors in in vivo (filled bars) and in vitro studies (empty bars). In the case of in vivo studies the GSH concentration was calculated assuming pH value 7.1 [33] and temperature 37°C. In the case of in vitro studies GSH concentration was determined by EPR using DNB in the homogenates from the same tumors (see Materials and Methods).

Discussion

Griffith and McConnell [34, 35] were the first to use thiol-specific nitroxide with maleimide function to bind it to the thiol groups of proteins in pioneer work in the EPR spin labeling field. Later on the thiol-specific mononitroxides were frequently used for protein thiol labeling [34–38] and EPR determination of the accessible thiol groups in various macromolecular structures, such as human plasma low-density lipoproteins [39] or erythrocyte membranes [40]. The EPR characterization of the protein sulfhydryl groups is based on the immobilization of the nitroxide upon binding to a macromolecular structure. This approach normally requires purification of the sample from the unbound label and can not be used in vivo. Moreover, application of thiol-specific mononitroxides to the EPR measurement of glutathione or cysteine is hardly possible due to insignificant EPR spectral changes of the label upon binding to low-molecular-weight compounds. This drawback was overcome by the development of the disulfide nitroxide biradicals, DNB [17, 18]. DNB, being paramagnetic analogs of widely used Ellman’s reagent [9], react with thiols via the thiol-disulfide exchange reaction (1). The principal advantage of the DNB reagents over monoradical labels is the drastic EPR spectral changes even in the case of the reaction with low-molecular-weight thiols [26] (see Fig. 1).

The developed DNB of imidazoline [17] and imidazolidine [18] types are lipophilic compounds (lipophilicity coefficients of about 200 [18]), which easily diffuse across cellular membranes where they react with intracellular thiols. Imidazoline label, iDNB [17], reacts with GSH at physiological pH within a few seconds, therefore, providing a fast reliable EPR approach for GSH determination in optically nontransparent samples. The authors [17, 41–48] used the iDNB label to measure GSH and/or total thiols in various cells and cellular homogenates. The quantitative GSH measurement using the fast reacting iDNB is based on the prior calibration of the EPR spectral changes to the thiol concentration and requires application of an excess of label over GSH. The latter requirement results in the complete consumption of the intracellular GSH during the measurement and, therefore, limits this approach from being use in vivo.

The development of slow-reacting imidazolidine DNB, (Scheme 1) [18] provides an opportunity to quantitatively measure thiol content from the analysis of the EPR spectral change kinetics (see Fig. 2). This kinetics approach looses the attractive simplicity of the static EPR measurements using iDNB label [20, 26] but gains a decisive advantage by using low concentrations of the label compared with the thiol content. This important advantage makes the approach less invasive and, therefore, applicable in vivo. However, the in vivo application of DNB for thiols/GSH measurement might be complicated by the possible influence of the label diffusion rate into the intracellular space, contribution of the protein thiols to the reaction (1) and reduction of the nitroxide moiety, making it difficult to extract quantitative information from the EPR spectral kinetics. Fortunately, the diffusion of the DNB labels into the intracellular space did not limit the reaction (1) even for the fast-reacting iDNB [18, 26, 49]. Another favorable aspect is the observation of extremely low reaction rates of the DNB with the protein thiols, e.g. the rate constants of the DNB reaction with SH-groups of human serum albumin and hemoglobin were less or about 1% of the corresponding values for GSH [18]. Taking into account that GSH is a major intracellular thiol compound present in cytosol in concentrations from 1 to 10 mM, one may expect a predominant contribution of GSH to the reaction (1).

Most of the present studies were performed using DNB label with 15N isotope labeled NO fragments. The isotopic substitution did not influence chemical reactivity of the DNB probe towards thiols while it resulted in decreasing the number of EPR spectral lines and about a two-fold increase in the SNR. Complete splitting of the disulfide bond of the upon reaction with GSH resulted in a 3 fold increase of the “monoradical” peak intensity, Im (Fig. 1). The reduction of one of the NO fragments of the also results in increase, but the maximal reduction-induced peak intensity increase is significantly lower, (see Fig. 4a). It provides a simple estimate of comparative contribution of the DNB reduction to the overall Im increase. For example, in our experiments the observed maximal increase of the Im in vivo (Fig. 5) exceeded the expected estimate of reduction-induced Im increase by one order of magnitude or more.

The other important aspects which have to be considered for the quantitative measurement of the tissue GSH from the kinetics of the reaction (1) is the dependences of the rate constant on pH and temperature. In the present paper we carefully studied pH dependence of the rate constant of the reaction (1) at room temperature and 37°C (see Fig. 2 and 3) providing reference data for the measurements in living tissues.

Intracellular GSH has been shown to be one of the major factors modulating tumor response to a variety of commonly used anti-neoplastic agents, including its important role in resistance towards cisplatin drugs [50]. Overall, it was concluded that in situations where GSH plays an important part in determining tumor response to a particular treatment, nude mouse xenografts may represent the most appropriate experimental model system [32]. Recently we demonstrated that sensitivity to cisplatin correlates with a higher redox environment in ovarian xenograft tumors in mice measured in vivo using EPR and label, and with higher tissue GSH content measured in vitro [31]. In the present paper we apply the DNB label to quantitatively measure GSH content in vivo in ovarian xenograft tumors in mice. The observed in vivo kinetics showed about two-fold increase of EPR “monoradical” peak intensity during the first 5–10 minutes (Fig. 5), therefore supporting the insignificant contribution of the probe bioreduction in this increase. The fitting of the initial part of the kinetics supposing the dominant contribution of the reaction (1) of DNB with GSH, yields the values of intracellular GSH concentration presented in Fig. 6. The observed concentration of GSH in cisplatin resistant tumors (3.3 mM) almost twice exceeded GSH content in cisplatin sensitive tumors (1.8 mM) and is in agreement with the values measured in isolated tissue homogenates (see Fig. 6) and previously reported data [31, 32]. The authors [32] reported that GSH content of human ovarian tumor cells obtained from mouse xenografts grown as ascites or as solid tumors was 4.7±2.1 mM. Note that GSH contents found in the human ovarian tumors from primary biopsies were on average only slightly higher (30%) than those obtained in nude mouse xenografts of human ovarian cancer [32].

In summary, this work is the first to employ DNB labels to measure GSH concentration in vivo using L-band EPR spectroscopy. Application of isotopically substituted compound provided an improvement in sensitivity, which is important for in vivo application. In addition, 15N isotopic substitution decreases the number of spectral lines making the label more attractive for potential imaging applications [31]. The developed EPR approach for GSH measurement in vivo might become a valuable experimental tool particularly when considering GSH redox status as useful indicator of disease risk in animals and humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by NIH grants KO1 EB03519, R21 CA132068 and R01 CA102264. VVK would like to acknowledge Prof. Harold M. Swartz (Dartmouth Medical School) for his continued encouragement and enthusiastic vision of the potential EPR has for in vivo GSH measurements.

Abbreviations

- CysSH

cysteine

- DNB

disulfide nitroxide biradical

- DTPA

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione disulfide

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- SNR

signal-to-noise ratio

APPENDIX

Synthesis of the disulfide nitroxide biradicals, and

The biradicals (10b) and (10a) were synthesized as follows (see Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthetic route to the isotopically substituted biradicals (10b) and (10a).

For the synthesis of the isotopically substituted nitroxides 8 (Scheme 2), deuterated compounds with 99% or more content of D were used: ammonia-d3 26 % solution in D2O, acetone-d6, ethanol-d6, sodium borodeuteride (Cambridge Isotope laboratories, Inc.), deuterium oxide, methyl alcohol-d1 (Acros), dimethyl sulfate-d6 (Aldrich) and sodium nitrite (15N, 98%+) from Cambridge Isotope laboratories, Inc.

Alkene 1a was synthesized by dehydration of 1,1,1-trideutero 2-trideuteromethyl butanole-2 by heating with diluted non-deuterated sulfuric acid (cf. [51]). The synthesis of nitroso chloride 2a was carried out in non-deuterated water as well, assuming that deuterium diminution on this step is impossible. Next steps – the synthesis of hydroxyamino oxime 3a, hydroxyamino ketone 4a and imidazoline 5a were carried out in deuterated solvents with the use of deuterated reagents, which excluded the deuterium diminution. Deutero-exchange in the methyl group of hydroxyamino ketone 4a (X = H) was carried out by fifteen-fold incubating–evaporating procedure of hydrochloride 4a in CH3OD. According to the data, published in ref. [52] the full exchange of protium on deuterium is achieved after three-fold procedure. Nevertheless, chromato-masspectroscopy analysis of imidazoline 5a (X = D) showed that the degree of deutero-exchange even at fifteen-fold procedure is low; the isotopic content of a sample of 5a was: 5H – 17%, 4H – 47%, 3H – 17%, 2H – 5%. The possibility of deuterium loose from the methyl group in position 2 of imidazoline 5a heterocycle is excluded - the condensation reaction was carried out in entirely deuterated medium, hence, protium atoms in a molecule of imidazoline 5a (X = D) mainly are located in 4-methyl group and one atom, on average, in 5-methyl groups. The deuterium content could not change noticeably on step 5a→6a; enamine 7a (X = D) was synthesized from methyl sulfate 6a (X = D) in deuterated water that was much more efficient for deutero-exchage in 4-methyl group. Thus chromato-masspectroscopy analysis of bromomethyl derivative 9a (X = D) showed, that the content of protium becomes noticeably lower than in starting imidazoline 5a: none H – 35%, 1H – 38%, 2H - 15%. Thus, protium (one atom per a molecule 9a (X = D)) is located in 5-methyl group. If usual methanol is used as a solvent for reduction reaction of bromoenamine 8a (X = D), resulting imidazolidine 9’a (X = D) contains: 1H – 23%, 2H – 44%, 3H – 18 % due to the insertion of protium into bromomethyl group. It should be noted, that the line width in EPR spectrum of 9a and 9’a is almost the same, and hence, isotopic content of bromomethyl group is inessential. The deuterium looses in the synthesis of biradicals 10a, 11a are excluded, and hence, the isotopic content of these compounds is the same as of their precursors – bromomethyl derivatives 9.

2-(Methyl-d3)-2-butene-1,1,1-d3 1a was synthesized from corresponding alcohol by dehydration in 30% H2SO4 and the alcohol was prepared by treating of acetone-d6 with the methyl magnesium iodide.

The 15N-hydroxylamine hydrochloride was synthesized from sodium 15N-nitrite according the procedure described in ref. [53].

Nitroso chlorides 2 were prepared from the appropriate olefins by reaction with sodium nitrite and hydrochloric acid [54].

The 1,2-hydroxylaminooximes 3 were synthesized by reaction of the dimeric nitroso chlorides of olefins 2 with 15N-hydroxylamine hydrochloride similarly to the described procedure [55].

3-(15N-Hydroxyamino)-3-methyl-d3-butan-1,1,1-d3-2-one oxime acetate 3a. A solution of 3.9 g (47 mmol) of sodium acetate in 6 ml of water was added to a solution of 3.3 g (47 mmol) of 15N-hydroxylamine hydrochloride in 6 ml water. The solution of 9.7 g (34 mmol) 2-chloro-2-(methyl-d3)-3-nitrosobutane-1,1,1-d3 dimer 2a in 36 ml EtOH was added to a mixture and one was boiled for 3h; the NaCl precipitate was then filtered off. Acetic acid (5 ml) was added and ethanol was evaporated at reduced pressure. The residue was washed with diethyl ether (3×20 ml); an aqueous solution was saturated with NaCl and extracted with ethyl acetate (10×30 ml). 1.5 ml of acetic acid was added to combined extract and a solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was treated with hexane, the precipitate of 1.2-hydroxylaminooxime 3a [52] was filtered off and recrystallized from ethyl acetate to give 3.0g (32 %) of 3a.

Compound 3b was synthesized similarly from 2.7 g (39 mmol) of 15N-hydroxylamine hydrochloride and 8.0 g (29 mmol) of nitroso chlorides dimer 2b, the yield was 2.7 g (36 %). The yield was counted on 15N-hydroxylamine hydrochloride in both cases.

3-(Hydroxyamino)-3-methylbutan-2-ones 4 were synthesized by acidic hydrolysis of 1,2-hydroxyaminooximes 3 with concentrated hydrochloric acid [52].

3-(15N-Hydroxyamino)-3-(methyl-d3)-butane-4,4,4-d3-2-one hydrochloride 4a (X=H). The solution of 2,6 g of 3-(15N-hydroxyamino)-3-methyl-d3-butan-1,1,1-d3-2-one oxime acetate 3a in 6 ml concentrated hydrochloric acid was kept for 18 h at room temperature. The precipitated NH2OH·HCl was filtered off and washed with a small amount of cooled concentrated hydrochloric acid. The filtrate was evaporated to dryness at reduced pressure and the residue was recrystallized from acetonitrile to give 1.5 g (71%) of 3-(15N-hydroxyamino)-3-(methyl-d3)-butane-4,4,4-d3-2-one hydrochloride 4a (X=H).

3-(15N-Hydroxyamino)-3-methyl-butan-2-one 4b (X=H) was synthesized from 2.7 g of 1,2-hydroxyaminooxime 3b in the same manner with the yield 1.7 g (77%).

In order to prepare 3-(15N-hydroxyamino)-1.3-(dimethyl-d6)-butane-4.4.4-d3-2-one hydrochloride 4a (X=D), the solution of 1.5g 3-(15N-hydroxyamino)-3-(methyl-d3)-butane-4,4,4-d3-2-one hydrochloride 4a (X=H) in 10 ml of CH3OD was kept for 1h and then evaporated to dryness. The procedure was repeated 15 times [52].

15N-Imidazoline 5 was prepared similarly to ref. [56].

4-Methyl-2,2,5,5-(tetramethyl-d12)-2,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-1-ol-15N 5a (X=H). A solution of 5.25 ml of ammonia-d3 26 % solution in D2O, 1.5 g 1.2-hydroxyaminoketone 4a and 3.8 ml of acetone-d6 was kept for 4 h. The acetone was evaporated and the aqueous solution was extracted with ether (4×10ml). The combined ether extracts were dried with MgSO4, ether solution was evaporated at reduced pressure; the residue was recrystallized from heptane; the yield was 1.0 g (63%) (cf. [52]).

2,2,4,5,5-(Pentamethyl)-2,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-1-ol-15N 5b (X=H) was synthesized similarly from 1.7g (10 mmol) of 1.2-hydroxylaminoketone 4b (X=H), 4.5 ml acetone and 6.2 ml of ammonia 26 % water solution with the yield 1.1g (69%).

The methylsulfates 6 and bromoenamines 9 were synthesized using a modified procedure taken from [51].

4-Methyl-2,2,3,5,5-(pentamethyl-d15)-2,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-3-ium-1-oxyl 1-15N methyl sulfate-d3 6a (cf. [52]). The suspension of 1.0g (5.8 mmol) of imidazoline 5 and 5.0 g MnO2 in 25 ml hexane was stirred for 1h at room temperature; oxidant excess was filtered off and filtrate was evaporated at reduced pressure. The residue, 4-methyl-2,2,5,5-(tetramethyl-d12)-2,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-1-oxyl 1-15N, was dissolved in 30 ml anhydrous ether and 2 ml of dimethyl sulfate-d6 was then added to a solution. The reaction mixture was kept for 30 min at 20 °C, the ether was removed at reduced pressure and the residue was kept at 30 °C for 20 min. The reaction mixture turned almost solid, after that the precipitate formed was diluted with anhydrous ether, filtered off and washed with anhydrous ether. Yield 1.4 g (78%).

Similarly, 2,2,3,4,5,5-hexamethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-3-ium-1-oxyl 1-15N methyl sulfate 1-15N, 6b, was prepared from 1.1g (7.0 mmol) of imidazoline 5b with the yield 1.4 g (70%).

4-(Bromomethyl-d2)-4-deutero-2,2,3,5,5-(pentamethyl-d15)-imidazolidine-1-oxyl 1-15N 9a. A mixture of a solution of 0.71 g (2.3 mmol) methyl sulfate 6a in D2O (10 ml) and 30 ml of ether was alkalified on shaking to pH 9–10 with NaHCO3. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous one was extracted with ether (2×30 ml). The combined extract of 4-(methylene-d2)-2,2,3,5,5-(pentamethyl-d15)-imidazolidine-1-oxyl 1-15N 7a was dried with MgSO4 at 0 °C for 15 min, the desiccant was filtered off and 0.70 ml triethylamine was added to the filtrate. A solution of 40 mg (0.25 mmol) bromine in 4 ml anhydrous chloroform was then added dropwise with stirring and cooling to −5 °C to resulted solution of enamine. Triethylamine hydrobromide precipitate formed was filtered off, and filtrate was evaporated to dryness at a reduced pressure at 20 °C. The residue was treated twice with 20 ml of hexane, the solution was separated from sticky residue, and combined solution of 4-(bromomethylene-d1)-2.2.3.5.5-(pentamethyl-d15)-imidazolidine-1-oxyl 1-15N 8a was evaporated at reduced pressure at 20 °C. The residue was dissolved in 30 ml of cooled to 0 °C methanol-d1 and 0.21 g (5.0 mmol) NaBD4 was added in portions with stirring and cooling to 0 °C to the solution. Stirring was continued for 30 min at 0 °C and then a solvent was removed at reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in the mixture of 25 ml ether and 20 ml of saturated brine, ether solution was separated and washed with water (2×15 ml) and then dried with MgSO4. The solution was evaporated and the residue, 4-(bromomethyl-d2)-4-deutero-2,2,3,5,5-(pentamethyl-d15)-imidazolidine-1-oxyl 1-15N, 9a, was purified by chromatographing on silica gel with hexane-ether (4:1) mixture as eluent. Yield was 50 mg (8.0 %), mp 82 °C (from hexane), lit. mp 81–83 °C [57]

4-(Bromomethyl-d1)-4-deutero-2,2,3,5,5-(pentamethyl-d15)-imidazolidine-1-oxyl 15N 9’a was prepared from 4-(bromomethylene-d1)-2.2.3.5.5-(pentamethyl-d15)-imidazolidine-1-oxyl 1-15N 8a, by reduction with NaBD4 in methanol in the same manner with the yield 31 %.

Similarly, 0.18 g (18 %) of 4-bromomethyl-2,2,3,5,5-pentamethylimidazolidine-1-oxyl 1-15N 9b was obtained from 1.1 g (3.9 mmol) of 2.2.3.4.5.5-hexamethyl-3-imidazolinium-1-oxyl methyl sulfate 1-15N 6b.

Bis[4-deutero-2,2,3,5,5-(pentamethyl-d15)-1-oxyl-imidazolidin-4-ylmethyl-d2]-disulfide 1-15N 10a. A solution of 50 mg (0.19 mmol) of compound 9a and 15 mg (0.20 mmol) thiourea in 1 ml ethanol-d1 was boiled for 15 min. then 1 ml of ammonia-d3 26 % solution in D2O and 2 ml of ether were added, and the mixture was stirred for 3.5 h at room temperature. Then a solution of 0.05 g K3[Fe(CN)6] in 0.1 ml of 5% water solution of NaOH was added and stirring was continued for more 40 min. Ether solution was separated and a water solution was extracted with ether (3×5 ml). Combined extract was dried with anhydrous MgSO4, the solution was evaporated at reduced pressure and disulfide 10a was purified chromatographically on silica gel with ether as the eluent. The yield was 20 mg (48%), dark orange oil that turned crystalline below 0 °C.

Similarly, bis(2,2,3,5,5-pentamethyl-1-oxyl-imidazolidin-4-ylmethyl)-disulfide 1-15N 10b was obtained from 0.18 g (0.72 mmol) of 4-bromomethyl-2,2,3,5,5-pentamethylimidazolidine-1-oxyl 1-15N 9b with the yield 51 mg (36 %).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arrigo AP. Gene expression and the thiol redox state. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27(9–10):936–44. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samiec PS, Drews-Botsch C, Flagg EW, Kurtz JC, Sternberg P, Jr, Reed RL, Jones DP. Glutathione in human plasma: decline in association with aging, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24(5):699–704. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sies H. Glutathione and its role in cellular functions. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27(9–10):916–21. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30(11):1191–212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herzenberg LA, De Rosa SC, Dubs JG, Roederer M, Anderson MT, Ela SW, Deresinski SC, Herzenberg LA. Glutathione deficiency is associated with impaired survival in HIV disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(5):1967–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi R, Milzani A, Dalle-Donne I, Giustarini D, Lusini L, Colombo R, Di Simplicio P. Blood glutathione disulfide: in vivo factor or in vitro artifact? Clin Chem. 2002;48(5):742–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yelinova V, Glazachev Y, Khramtsov V, Kudryashova L, Rykova V, Salganik R. Studies of human and rat blood under oxidative stress: changes in plasma thiol level, antioxidant enzyme activity, protein carbonyl content, and fluidity of erythrocyte membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;221(2):300–3. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi C, Tanaka R, Okuda Y, Ikota N, Yamamoto H, Urano S, Ozawa T, Anzai K. Quantitative measurements of oxidative stress in mouse skin induced by X-ray irradiation. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2005;53(11):1411–5. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82(1):70–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patsoukis N, Georgiou CD. Determination of the thiol redox state of organisms: new oxidative stress indicators. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378(7):1783–92. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patsoukis N, Georgiou CD. Fluorometric determination of thiol redox state. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;383(6):923–9. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal Biochem. 1969;27(3):502–22. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terpstra M, Henry PG, Gruetter R. Measurement of reduced glutathione (GSH) in human brain using LCModel analysis of difference-edited spectra. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(1):19–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis JA, Schleich T. 13C-NMR spectroscopic studies of 2-mercaptoethanol-stimulated glutathione synthesis in the intact ocular lens. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1265(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)00195-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livesey JC, Golden RN, Shankland EG, Grunbaum Z, Wyman M, Krohn KA. Magnetic resonance spectroscopic measurement of cellular thiol reduction-oxidation state. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22(4):755–7. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90518-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potapenko DI, Bagryanskaya EG, Grigoriev IA, Maksimov AM, Reznikov VA, Platonov VE, Clanton TL, Khramtsov VV. Quantitative determination of SH groups using 19F NMR spectroscopy and disulfide of 2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-4-mercaptobenzoic acid. Magn Reson Chem. 2005;43(11):902–9. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khramtsov VV, Yelinova VI, Weiner LM, Berezina TA, Martin VV, Volodarsky LB. Quantitative determination of SH groups in low- and high-molecular-weight compounds by an electron spin resonance method. Anal Biochem. 1989;182(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90718-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khramtsov VV, Yelinova VI, Glazachev Yu I, Reznikov VA, Zimmer G. Quantitative determination and reversible modification of thiols using imidazolidine biradical disulfide label. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1997;35(2):115–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(97)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swartz HM, Khan N, Khramtsov VV. Use of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy to evaluate the redox state in vivo. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(10):1757–71. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khramtsov VV, Grigor’ev IA, Foster MA, Lurie DJ. In vitro and in vivo measurement of pH and thiols by EPR-based techniques. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6(3):667–76. doi: 10.1089/152308604773934431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrews PA, Jones JA, Varki NM, Howell SB. Rapid emergence of acquired cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) resistance in an in vivo model of human ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Commun. 1990;2(2):93–100. doi: 10.3727/095535490820874641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuppusamy P, Afeworki M, Shankar RA, Coffin D, Krishna MC, Hahn SM, Mitchell JB, Zweier JL. In vivo electron paramagnetic resonance imaging of tumor heterogeneity and oxygenation in a murine model. Cancer Res. 1998;58(7):1562–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parmon VN, Zhidomirov GM. Calculation of the E.S.R. spectrum shape of the dynamic biradical system. Molecular Physics. 1974;27:367–375. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luckhurst GR. Biradicals as spin probes. In: Berliner LJ, editor. Spin Labelling. New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parmon VN, Kokorin AI, Zhidomirov GM. Stable Biradicals. Nauka, Moscow: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khramtsov VV, Volodarsky LB. Use of imidazoline nitroxides in studies of chemical reactions. ESR measurements of the concentration and reactivity of protons, thiols and nitric oxide. In: Berliner LJ, editor. Spin labeling. The next Millennium. Vol. 14. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 109–180. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benesch RE, Benesch R. The Acid Strength of the -SH Group in Cysteine and Related Compounds. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:5877–5881. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabenstein DL. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the acid-base chemistry of amino acids and peptides. I. Microscopic ionization constants of glutathione and methylmercury-complexed glutathione. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:2797–2803. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glebska J, Skolimowski J, Kudzin Z, Gwozdzinski K, Grzelak A, Bartosz G. Pro-oxidative activity of nitroxides in their reactions with glutathione. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(3):310–6. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkelstein E, Rosen GM, Rauckman EJ. Superoxide-dependent reduction of nitroxides by thiols. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;802:90–98. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bratasz A, Selvendiran K, Wasowicz T, Bobko A, Khramtsov VV, Ignarro LJ, Kuppusamy P. NCX-4040, a nitric oxide-releasing aspirin, sensitizes drug-resistant human ovarian xenograft tumors to cisplatin by depletion of cellular thiols. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2008;6(9) doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee FY, Vessey A, Rofstad E, Siemann DW, Sutherland RM. Heterogeneity of glutathione content in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1989;49(19):5244–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhujwalla ZM, McCoy CL, Glickson JD, Gillies RJ, Stubbs M. Estimations of intra- and extracellular volume and pH by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy: effect of therapy on RIF-1 tumours. Br J Cancer. 1998;78(5):606–11. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffith OH, McConnell HM. A nitroxide-maleimide spin label. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1966;55:8–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berliner LJ, Grunwald J, Hankovszky HO, Hideg K. A novel reversible thiol-specific spin label: papain active site labeling and inhibition. Anal Biochem. 1982;119(2):450–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabbita SP, Subramaniam R, Allouch F, Carney JM, Butterfield DA. Effects of mitochondrial respiratory stimulation on membrane lipids and proteins: an electron paramagnetic resonance investigation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1372(2):163–73. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hensley K, Carney J, Hall N, Shaw W, Butterfield DA. Electron paramagnetic resonance investigations of free radical-induced alterations in neocortical synaptosomal membrane protein infrastructure. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;17(4):321–31. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coan C, Keating S. Reactivity of sarcoplasmic reticulum adenosinetriphosphatase with iodoacetamide spin-label: evidence for two conformational states of the substrate binding sites. Biochemistry. 1982;21(13):3214–20. doi: 10.1021/bi00256a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kveder M, Krisko A, Pifat G, Steinhoff HJ. The study of structural accessibility of free thiol groups in human low-density lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1631(3):239–45. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soszynski M, Bartosz G. Decrease in accessible thiols as an index of oxidative damage to membrane proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23(3):463–9. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiner LM, Hu H, Swartz HM. EPR method for the measurement of cellular sulfhydryl groups. FEBS Lett. 1991;290(1–2):243–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81270-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busse E, Zimmer G, Kornhuber B. Plasma-membrane fluidity studies of murine neuroblastoma and malignant melanoma cells under irradiation. Strahlenther Onkol. 1992;168(7):419–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Busse E, Zimmer G, Schopohl B, Kornhuber B. Influence of alpha-lipoic acid on intracellular glutathione in vitro and in vivo. Arzneimittelforschung. 1992;42(6):829–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busse E, Zimmer G, Kornhuber B. Intracellular changes of HeLa cells after single or repeated treatment with cytostatics. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43(3):378–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balcerczyk A, Bartosz G. Thiols are main determinants of total antioxidant capacity of cellular homogenates. Free Radic Res. 2003;37(5):537–41. doi: 10.1080/1071576031000083189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balcerczyk A, Grzelak A, Janaszewska A, Jakubowski W, Koziol S, Marszalek M, Rychlik B, Soszynski M, Bilinski T, Bartosz G. Thiols as major determinants of the total antioxidant capacity. Biofactors. 2003;17(1–4):75–82. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520170108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bratasz A, Khramtsov VV, Kuppusamy P. A modified Tietze assay for the determination of thiols in intact cells and tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(Suppl 1):S147. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bratasz A, Weir NM, Parinandi NL, Zweier JL, Sridhar R, Ignarro LJ, Kuppusamy P. Reversal to cisplatin sensitivity in recurrent human ovarian cancer cells by NCX-4016, a nitro derivative of aspirin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(10):3914–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511250103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khramtsov VV, Gorunova TE, Weiner LM. Monitoring of enzymatic activity in situ by EPR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179(1):520–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rabik CA, Dolan ME. Molecular mechanisms of resistance and toxicity associated with platinating agents. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(1):9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volodarsky LB, Reznikov VA, Grigor’ev IA. Chemical Properties of heterocyclic nitroxides. In: Volodarsky LB, editor. Imidazoline nitroxides. Vol. 1. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Fl: 1988. pp. 29–76. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glazachev YI, Grigor’ev IA, Reijerse EJ, Khramtsov VV. EPR Studies of 15N- and 2H-Substituted pH-Sensitive Spin Probes of Imidazoline and Imidazolidine Types. Appl Magn Reson. 2001;20:489–505. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karyakin YV, Angelov II. Pure Chemical Substances (Chistye khimicheskie veshchestva) Khimiya, Moscow, USSR: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Volodarsky LB, Grigor’ev IA. Synthesis of heterocycling nitroxides. In: Volodarsky LB, editor. Imidazoline Nitoxides. Vol. 1. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Fl: 1988. pp. 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Volodarsky LB, Putsykhin YG. Zh Org Khim. 1967;3(9):1686–1694. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sevastyanova TK, Volodarsky LB. Bull Acad Sci USSR. 1972;21:2276. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reznikov VA, Volodarsky LB. Haloderivatives of imidazolidine nitroxyl radicals and their properties. Izvestiya Sibirskogo Otdeleniya Akademii Nauk SSSR, Seriya Khimicheskikh Nauk. 1984;3:89–97. [Google Scholar]