Abstract

Background/Aim

To assess pathophysiology in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Methods

122 IBS patients (3 male) and 41 healthy females underwent: questionnaires (symptoms, psychology), autonomic, gut transit, gastric volumes (GV), satiation, rectal compliance and sensation (thresholds and pain ratings) testing. Proportions of patients with abnormal (<10th and >90th percentiles) motor or sensory functions according to bowel symptoms [constipation (C), diarrhea (D), mixed (M)], pain/bloat and number of primary symptoms were estimated.

Results

IBS subgroups (C, D, M) were similar in age, gastric and small bowel transit, satiation, GV, rectal compliance, sensory thresholds or pain ratings. IBS was associated with BMI, somatic symptoms, anxiety and depression scores. Significant associations were observed with colonic transit (IBS-C [p=0.078] and IBS-D [p<0.05] at 24 h; IBS-D [p<0.01] and IBS-M [p=0.056] at 48 h): 32% IBS had abnormal colonic transit: 20.5% at 24 h and 11.5% at 48 h. Overall, 20.5% IBS patients had increased sensation to distensions: hypersensitivity (<10th percentile thresholds) in 7.6%, and hyperalgesia (pain sensation ratings to distension >90th percentile for ratings in health) in 13%. Conversely, 16.5% of IBS patients had reduced rectal sensation. Pain >6 times per year and bloating were not significantly associated with motor, satiation, or sensory functions. Endorsing 1–2 or 3–4 primary IBS symptoms were associated with abnormal transit and sensation in IBS.

Conclusion

In tertiary referral (predominantly female) patients with IBS, colonic transit (32%) is the most prevalent physiological abnormality; 21% had increased and 17% decreased rectal pain sensations. Comprehensive physiological assessment may help optimize management in IBS.

Keywords: hypersensitivity, hyperalgesia, transit, motility, functional gastrointestinal disorders, affective

INTRODUCTION

The pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) includes abnormalities of motility, sensation, psychosocial and mucosal defense (1). Different laboratories have reported on individual pathophysiological features of interest and have documented abnormal transit (2–4), colonic motility (5, 6), rectal sensation (7,8), brain function on imaging studies (9,10) mucosal structure and function (11–14) or, in some studies, low grade inflammation (15–18). However, few studies comprehensively appraised more than one or two putative mechanisms in a sufficiently large number of patients.

Another area of controversy is the frequency of overlap of functional dyspepsia and IBS with prevalence in epidemiological studies ranging from 30 to 80% (19,20). Patients with IBS and rectal hypersensitivity also have gastric hypersensitivity (21–23). The prevalence of abnormal upper gastrointestinal motor functions in a large group of patients with IBS is unclear.

In IBS, there are also patients with alteration of bowel function (or mixed, IBS-M) which may be identified by symptoms (24); however, little is known about the pathophysiology of this subgroup. Autonomic dysfunction has been described in IBS patients (25–27), though the associations with motor and sensory dysfunctions in the same patients are unclear.

The aims of our study were: first, to comprehensively assess symptoms, psychological status, motor, sensory and autonomic functions in patients with IBS based on bowel dysfunction [constipation (C), diarrhea (D), and alternators/mixed (M)], and based on pain and bloating; second, to ascertain the proportion of IBS patients who have abnormal transit and increased or decreased sensation and to explore the association of increased sensation with abnormal psychological status; third, to assess the association between number of primary IBS symptoms and pathophysiology; and fourth, to appraise the relationship between abnormal gastric functions and symptoms of dyspepsia in patients with IBS.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In a single-center, prospective study, 122 IBS patients [by Rome II criteria (28)] were recruited over a 4-year period; 119 were female and 3 (all in the IBS-D group) were male. Patients were recruited from an administrative database of 850 patients residing within 200 miles of the Mayo Clinic based on their primary presentation with IBS. Questionnaire responses assessed the coexistence of other gastrointestinal symptoms, psychological disturbances, and the relationship of upper abdominal symptoms to meal ingestion. Forty-one female healthy controls underwent the same measurements and were concurrently recruited. The healthy participants had less than 4 positive (only mild severity permissible) out of 19 gastrointestinal symptoms on a screening questionnaire. Studies were conducted in the Clinical Research Unit at Mayo Clinic. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Eligibility criteria and allowable medications are detailed in the Appendix.

Questionnaires and Symptom Number

All participants filled in the following questionnaires: Bowel Disease Questionnaire [BDQ (29)] that included a checklist of somatic symptoms (leading to a somatic symptom score), Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) Inventory (30), and a general quality of life instrument [SCL-90 (31)].

Symptom number was based on the number of positive symptoms among the following: pain >6/yr, presence of bloating, bowel frequency <3 or 4 per week, or >12 per week, need to strain often (>25% of time), and stool consistency either often loose/watery or often hard. For each one of these symptoms, a score of 1 was assigned. The analysis of the relationship of symptom number and pathophysiology was based on 3 groups for number of primary IBS symptoms endorsed: 1–2, 3–4, or 5–6.

Assessment of Gastrointestinal and Autonomic Functions

The methods used to measure gastrointestinal transit, gastric volumes, satiation, rectal compliance and sensation as well as autonomic function are provided in the Appendix (on-line)..

Statistical Analyses

Primary Endpoints for Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoints were gastric emptying (GE) t1/2, colonic geometric center (GC) at 24 hours, fasting and postprandial gastric volume (GV), maximum tolerated nutrient drink volume (MTV); colonic compliance [pressure at half maximum volume (Pr 1/2)], sensory thresholds and ratings for pain and urgency in response to distensions. We computed the proportion of patients with abnormal colonic transit (GC at 24 h <1.43 or GC at 48 h <2.00 for slow transit and >3.87 at 24 h or >4.91 for accelerated transit), which were the 10th and 90th percentiles for transit in the normal healthy volunteers studied concurrently and recruited specifically for this study. Similarly, we identified patients with hypersensitivity for gas, urgency and pain as those with thresholds <10th percentile for healthy volunteers and patients with hyperalgesia as those with sensory ratings >90th percentile for healthy volunteers. The association between phenotype (the three IBS subtypes and controls) and the physiologic responses (except sensation thresholds, see below) was assessed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). To aid interpretation of the overall assessment of associations, three pairwise comparisons of each IBS phenotype with healthy controls (α=0.05) were examined to assess the association of specific IBS subtypes with physiologic responses.

Detailed description of statistical methods for all the endpoints and the sample size assessments are provided in the Appendix (on-line).

RESULTS

Participants

Participants’ demographics and key psychological data are shown in Table I. IBS subgroups were similar in age. IBS-D and IBS-M patients had higher BMI values than healthy volunteers and IBS-C subjects. Physical examination (all performed by one experienced gastroenterologist [MC]) identified features suggestive of pelvic floor dysfunction in 12 patients: 5 with IBS-C, 2 with IBS-D and 5 with IBS-M. All patients were referred to an evacuations disorder clinic and in 6 of 6 who attended the clinic, the diagnosis was confirmed on anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion test (3 IBS-C, 1 IBS-D, 2 IBS-M). They were referred to a physical medicine-based retraining program. The proportions of IBS patients and healthy controls on SSRI were not significantly different. Controls took SSRI predominantly for symptoms not related to depression, e.g. menopausal symptoms.

Table I.

Demographics and Key Psychological Data in 163 People [41 controls and 122 patients with IBS (data are mean ± SEM)]

| Healthy Controls | IBS-C | IBS-D | IBS-M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (# male) | 41 (0) | 49 (0) | 44 (3) | 29 (0) |

| Age | 33.6 ± 1.6 | 38.6 ± 1.5 | 35.4 ± 1.6 | 37.2 ± 2.2 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.1 ± 0.7 | 25.1 ± 0.4 | 28.9 ± 1.0 | 27.9 ± 0.8 |

| Anxiety score, HAD | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.4 |

| Depression score, HAD | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| % of group on SSRI | 12.2 | 18.7 | 25.0 | 20.0 |

| Somatization T score | 40.8 ± 0.9 | 47.5 ± 0.9 | 49.3 ± 1.2 | 48.8 ± 1.5 |

| SCL-90 GSI T score | 37.1 ± 1.3 | 44.1 ± 1.3 | 44.6 ± 1.5 | 44.6 ± 1.7 |

| Somatic symptom score | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| Tiredness (mmVAS) | 38.8 ± 2.8 | 31.2 ± 2.3 | 38.4 ± 2.9 | 34.4 ± 3.3 |

| Peace (mmVAS) | 31.4 ± 2.9 | 35.7 ± 3.1 | 44.9 ± 3.4 | 34.2 ± 3.9 |

| Worried (mmVAS) | 73.4 ± 2.7 | 65.3 ± 2.7 | 61.3 ± 3.0 | 68.0 ± 3.4 |

| Active (mmVAS) | 58.5 ± 2.9 | 62.3 ± 2.2 | 57.0 ± 2.8 | 59.3 ± 4.0 |

BMI = body mass index; HAD = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Inventory; SSRI= selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; GSI = general severity index

Completion of Physiological Studies and Missing Data

In general, more than 95% of all physiological studies were completed. Given the significant investigational burden required to complete all studies, the total number of studies does not always reach 122 for patients and 41 for healthy controls (e.g., 6 patients withdrew consent to undergo sensation studies). All data are provided, including the number of participants for each test.

A few subjects did not complete all assessments including some of the questionnaires (BDQ, SCL-90) used in the study, specifically: 1 gastric emptying, 3 small bowel transit, 4 gastric volume measurement, 6 rectal sensation studies, 2 BDQ and SCL-90 questionnaires. Thus, the analysis models and summary data are based on slightly different total numbers of subjects depending on the particular endpoint assessed.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Lower bowel symptoms were consistent with irritable bowel syndrome (Table IIA). The study also characterized upper abdominal pain precipitated by food ingestion or occurring immediately (0–30 minutes) or after 30–120 minutes after food (Table IIB): 95% of healthy controls experienced no such pain after food ingestion, whereas approximately 30% of IBS patients had postprandial pain, with the highest prevalence and the most severe pain (3 pain components versus 1) in patients with IBS-M.

Table II.

| Table II A. Key Gastrointestinal Symptoms (% of participants in each group reporting specified symptom) Based on Bowel Disease Questionnaire using Analysis Based on Bowel Function | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls | IBS-C | IBS-D | IBS-M | |

| Symptom | N=41 | N=49 | N=44 | N=29 |

| Abdo pain >6 times per year | 5 | 67 | 77 | 90 |

| Bloating/swelling of abdomen | 0 | 64 | 48 | 79 |

| Typical # BMs per week(in last year) | ||||

| 3–4 or less | 29 | 71 | 14 | 34 |

| 5–8 | 54 | 16 | 9 | 38 |

| 9–12 | 12 | 2 | 30 | 17 |

| More than 12 | 5 | 10 | 48 | 10 |

| Often needed to strain (>25% of BMs) | 0 | 57 | 5 | 45 |

| Stool consistency | ||||

| Often loose/watery(>25% of BMs) | 0 | 8 | 77 | 48 |

| Often hard (>25% of BMs) | 12 | 80 | 9 | 59 |

| Incomplete evacuation (% yes) | 17 | 92 | 73 | 79 |

| Sense of urgency (>25% of BMs) | 0 | 12 | 64 | 59 |

| Table IIB. Key Postprandial Symptoms (% of participants in each group reporting specified symptom) Based on Bowel Disease Questionnaire | ||||

| Healthy Controls | IBS-C | IBS-D | IBS-M | |

| Symptom | N=41 | N=49 | N=44 | N=29 |

| Pain immediately post-meal, 0–30min | 2 | 14 | 41 | 48 |

| Pain 30–120 min post-meal | 0 | 55 | 52 | 66 |

| NO post-meal pain component | 95 | 35 | 30 | 21 |

| Any 1 post-meal pain component | 2 | 20 | 32 | 17 |

| Any 2 post-meal pain component | 0 | 35 | 25 | 38 |

| All 3 post-meal pain components | 0 | 8 | 14 | 24 |

Psychological Characterization

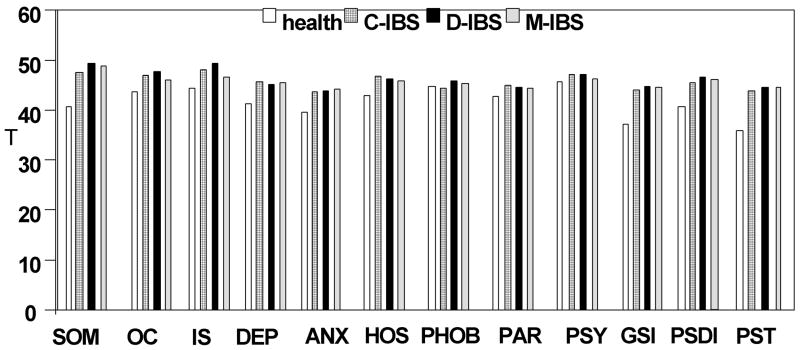

Table I lists key psychological data. There was an overall association of phenotype status with somatic symptom score; anxiety and depression scores; the somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, and general severity index scales of the SCL-90; and the scores for “peace” and “worried” states obtained during the barostat studies. As expected, relative to healthy controls, patients with IBS had higher somatic symptom score (Table I) and T scores for somatization, positive symptom total (PST), and general severity index (GSI) on SCL-90 (Figure 1). There were no significant associations for anxiety, depression, “tiredness” or “worry” scores with IBS subgroups.

Figure 1.

SCL-90 mean T scores. Note there are statistically significant differences in anxiety, depression, somatization, general severity index (GSI), and positive symptom total (PST).

Associations of Bowel Dysfunction Subgroup with Gastrointestinal Motor and Sensory Functions

Gastrointestinal and Colonic Transit

There was no overall association between subgroups based on bowel function and gastric emptying or colonic filling at 6 hours, a surrogate for small bowel transit (Table III).

Table III.

Key Gastrointestinal Physiological Data in 163 People [41 controls and 122 patients with IBS (data are mean ± SEM), based on bowel function subgroup]. For the number of participants undergoing each measurement, see methods section.

| Healthy Controls | IBS-C | IBS-D | IBS-M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (# male) | 41 (0) | 49 (0) | 44 (3) | 29 (0) |

| Fasting gastric volume, ml | 226 ± 11 | 229 ± 11 | 247 ± 11 | 222 ± 12 |

| Postprandial gastric volume, ml | 736 ± 13 | 740 ± 14 | 735 ± 14 | 770 ±17 |

| Δ postprandial fasting gastric volume, ml | 511 ± 13 | 525 ± 12 | 488 ± 12 | 548 ±19# |

| Proportion of gastric emptying at 2 h | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.03 |

| Gastric emptying, T1/2, min | 126.0 ± 4.4 | 126.8 ± 4.7 | 135.5 ± 5.6 | 137.6 ± 6.0 |

| Satiation: maximum tolerated volume, ml | 1028 ± 44 | 1044 ± 40 | 1046 ± 45 | 1106 ± 81 |

| Satiation: aggregate symptom score | 158 ±14 | 186 ±10 | 188 ± 12 | 184 ± 16 |

| Colonic filling at 6 h, % | 48 ± 5 | 54 ± 4 | 56 ± 3 | 44 ± 5 |

| Colon transit GC24* | 2.35 ± 0.16 | 2.03 ± 0.10 | 3.03 ± 0.19 | 2.34 ± 0.10 |

| Colon transit GC48** | 3.23 ± 0.18 | 3.0 ± 0.13 | 4.14 ± 0.17 | 3.94 ± 0.16 |

| Rectal compliance, Pr1/2, mmHg | 12.6 ± 0.8 | 12.5 ± 0.8 | 14.2 ± 0.6 | 14.0 ± 0.9 |

| Threshold for first sensation, mmHg | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 8.1 ± 0.8 |

| Threshold for gas, mmHg | 13.8 ± 1.5 | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 13.3 ± 1.2 | 14.5 ± 1.6 |

| Threshold for pain, mmHg | 29.1 ± 2.1 | 29.0 ± 2.0 | 31.0 ± 1.8 | 31.0 ± 2.2 |

| Threshold for urgency, mmHg | 17.5 ± 1.1 | 20.5 ± 1.6 | 18.8 ± 1.4 | 17.4 ± 1.2 |

| Sensation rating, pain 30 mmHg | 55.1 ± 4.5 | 52.5 ± 4.6 | 55.3 ± 4.2 | 54.3 ± 5.6 |

| Sensation rating, urgency 30 mmHg | 74.9 ± 2.8 | 71.5 ± 3.3 | 74.4 ± 2.5 | 74.3 ± 3.1 |

overall p<0.001;

overall p<0.001;

p=0.017 vs healthy controls;

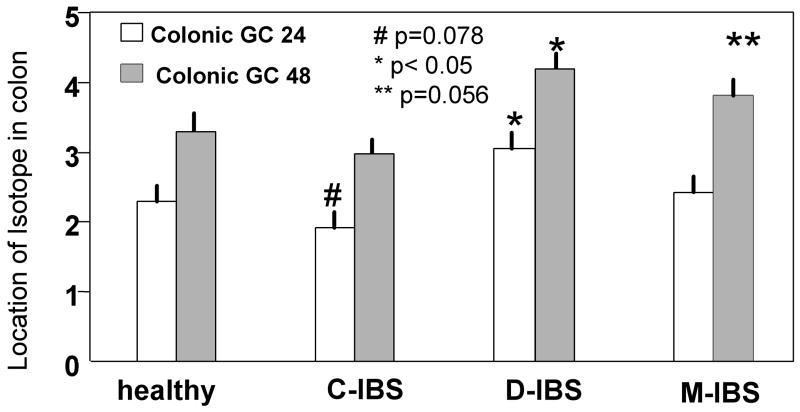

In contrast, significant associations of subgroups and colonic transit were observed (Table III, p<0.001 at 24 hours and at 48 hours). Unadjusted statistical comparisons between each IBS subgroup and healthy controls (Figure 2) suggest associations with colonic transit in IBS-C at 24 hours (p=0.078), IBS-D at 24 and 48 hours (p=0.035 and 0.017 respectively), and IBS-M at 48 hours (p=0.056).

Figure 2.

Comparison of colonic geometric center at 24 and 48 hours in healthy controls and IBS patients with different types of bowel dysfunction.

Colonic transit was abnormal (GC 24 <1.43 or >3.87) at 24 hours in 20.5% of IBS patients: 12% IBS-C and 3% IBS-M delayed transit; 30% IBS-D accelerated transit. At 48 hours, 4% more IBS-C patients had delayed transit, and 16% more IBS-D and 14% more IBS-M patients had accelerated transit. Thus, an additional 11.5% of IBS patients had abnormal colonic transit at GC 48 hours, for a total of 32% of patients with abnormal transit.

Gastric Volume, Satiation Volume and Post-nutrient Challenge Symptoms

There were no overall or subgroup associations with satiation volume aggregate or individual symptoms or with fasting and postprandial gastric volumes (Table III). The change in gastric volume after the 300 mL liquid nutrient meal indicated an overall (borderline significant) association with phenotype ( IBS subgroups and healthy controls, p=0.07), with the greatest volume change in IBS-M compared to healthy controls (p=0.055).

Gastric Functions in IBS Patients with Postprandial Aggravation of Upper Abdominal Pain

About 30% of IBS patients experienced this symptom. Table IV shows that there were no overall differences in the physiological measurements. Overall ANOVA for association of food-related pain and postprandial change in gastric volume was not significant (p=0.153). However, the comparison of postprandial change in gastric volume with 3 versus zero food-related pain components showed a possible association with more food-related pain (unadjusted p=0.050).

Table IV.

Gastric Function in Relation to Degree of Postprandial or Food Aggravation of Symptoms in Patients with IBS. Participants were subdivided by the number (0–3) of food related pain components: pain brought on by food; pain immediately after food ingestion within 0–30 min of meal; and pain experienced 30–120 minutes after the meal.

| zero | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N= | 75 | 30 | 39 | 17 |

| Gastric emptying T1/2, min | 136.1 ± 5.6 | 132.5 ± 8.0 | 129.8 ± 5.2 | 131.2 ± 6.3 |

| Max tolerated volume, ml | 1150 ± 62 | 993 ± 57 | 1007 ± 46 | 1110 ± 78 |

| Aggregate symptoms 30 min post-Ensure | 183 ±12 | 178 ±14 | 200 ±13 | 181 ± 20 |

| Fasting gastric volume, ml | 231 ± 12 | 247 ± 16 | 238 ± 14 | 228 ± 14 |

| Postprandial gastric vol, ml | 756 ± 16 | 757 ± 13 | 771 ± 19 | 707 ± 24 |

| Δ postprandial gastric vol, ml # | 525 ± 14 | 510 ± 17 | 533 ± 15 | 480 ± 23 * |

Overall ANOVA for association of food-related pain and postprandial change in gastric volume, p=0.153;

unadjusted comparison of 3 versus 0 food related pain components, p=0.05.

Rectal Sensation Thresholds and Compliance

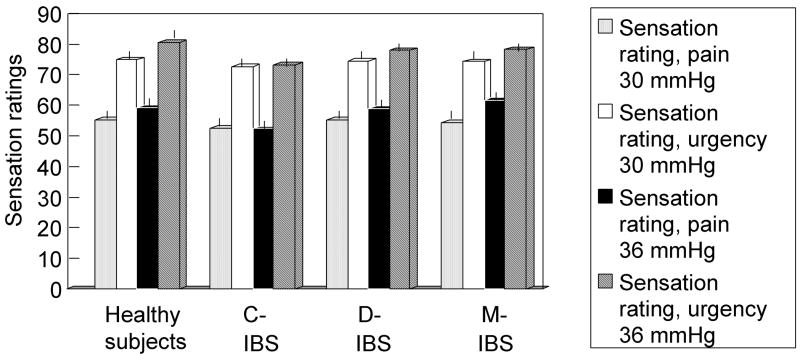

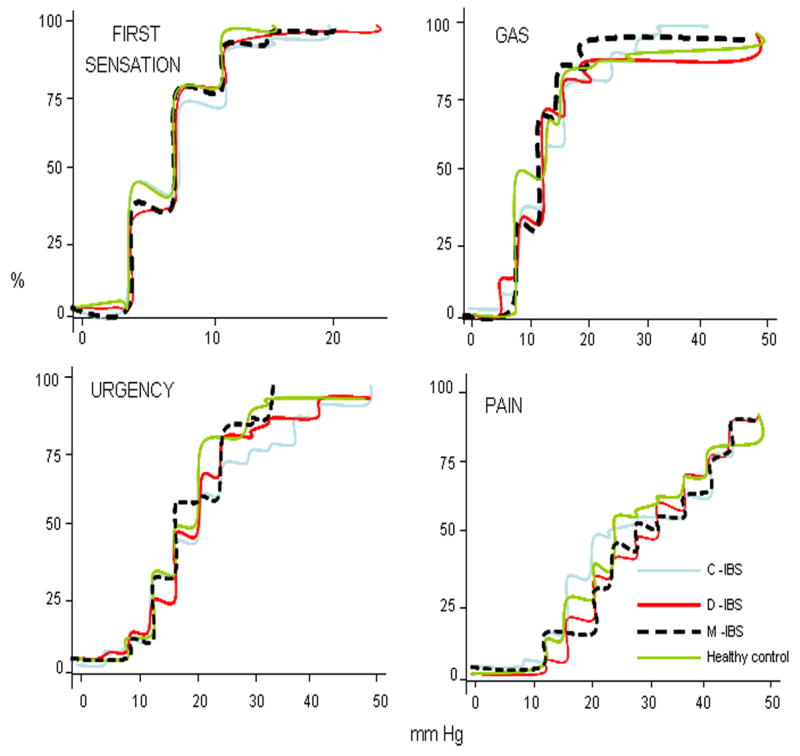

There were no associations detected for rectal compliance or any sensory thresholds for IBS overall or individual subgroups relative to controls (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percent of participants in each group reaching threshold for first sensation, gas, urgency and pain in response to step wise increase in intra-balloon pressure; note the significant overlap and lack of any significant differences in any group or any sensation relative to controls.

However, 6.8%, 11.1% and 7.6% of all IBS patients had hypersensitivity (thresholds <10th percentile for healthy volunteers) for gas, urgency and pain, respectively. Hypersensitivities to pain (lower threshold for pain), gas and urgency were respectively documented in 15, 9 and 11% IBS-C; 2, 10 and 12% IBS-D; and 3, 0 and 10% IBS-M.

Rectal Sensation Ratings

Ratings of urgency were borderline associated with anxiety scores (p=0.076), and ratings of pain were borderline associated with “active” and “worried” scores (p=0.094, 0.099, respectively). There were no significant associations of bowel function phenotype with the ratings of gas or pain. In contrast, there was a suggestion for an overall association of phenotype with ratings of urgency, with lowest urgency ratings in IBS-C compared to controls (p=0.11).

Rectal sensation ratings at 30 and 36 mmHg distensions are shown in Figure 4. At distensions of 36 mmHg above BOP, 11.3%, 18.1% and 16% of all IBS patients had increased sensory ratings for gas, urgency and pain respectively. Hyperalgesia (higher pain ratings) occurred with similar frequency (17%, 15%, 16%) in IBS-C, IBS-D and IBS-M, respectively. High urgency ratings occurred in 22% IBS-D and 21% IBS-M in contrast to only 12% in IBS-C. High gas ratings were observed in 7%, 13% and 16% of IBS-C, IBS-D and IBS-M, respectively.

Figure 4.

Sensory ratings of participants in each group for urgency and pain in response to random order, phasic increase in intra-balloon pressure; note the significant overlap for the sensation of pain and the lower sensory ratings for urgency in IBS-C (p=0.04 vs healthy controls).

The Appendix (on-line) includes information on the proportion of IBS patients with any abnormally increased or decreased rectal sensation of pain.

Association of Symptoms of Pain and Bloating with Gastrointestinal Motor and Sensory Functions

Table V provides the physiological measurements in patients based on the presence of pain and bloating. Tests for main effects of pain (>6 times per year), bloating (no/yes), adjusted for gender and BMI, indicate no significant associations detected for transit, satiation, gastric volumes, rectal compliance or sensory ratings of pain or urgency at 36 mmHg distensions (Table V-A). Similarly, rectal sensory threshold data were not associated with pain (>6 times per year) or with bloating [(no/yes) Table V-B].

Table V.

| Table V-A. Key Gastrointestinal Physiological Data in 163 People [41 controls and 122 patients with IBS (data are mean ± SEM), based on presence or absence of pain >6/yr and bloating]. One healthy and one IBS patient did not fill in questionnaire completely or undergo physiological test. None of the healthy volunteers reported bloating. For the number of participants undergoing each measurement, see methods section. GV =gastric volume, ml; PP= postprandial; MTV= maximum tolerated volume | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Health | IBS | IBS | IBS | IBS | |

| Pain >6/yr | Pain <6/yr or absent | Pain >6/yr | Pain <6/yr or absent | Bloating YES | Bloating NO | |

| Number | 2 | 38 | 93 | 28 | 75 | 46 |

| Fasting GV | 208 | 227 ± 12 | 234 ± 7 | 246 ± 21 | 240 ± 10 | 231 ± 10 |

| Postprandial (PP) GV | 699 | 740 ± 14 | 747 ± 9 | 776 ± 27 | 752 ± 12 | 757 ± 14 |

| Δ PP - fasting GV | 491 | 512 ± 14 | 513 ± 10 | 531 ± 16 | 512 ± 11 | 527 ± 13 |

| Gastric emptying, T1/2, min | 139 | 127 ± 4 | 132 ± 3 | 134 ± 8 | 131 ± 4 | 134 ± 5 |

| MTV, ml | 902 | 1040 ± 47 | 1050 ± 33 | 1096 ± 68 | 1031 ± 37 | 1109 ± 50 |

| Aggregate symptom score | 115 | 159 ± 15 | 185 ± 8 | 194 ± 15 | 191 ± 9 | 180 ± 12 |

| Colonic filling at 6 h, % | 60 | 48.9 ± 5.2 | 51.5 ± 2.8 | 53.6 ± 5.1 | 50.9 ± 3.1 | 53.8 ± 3.9 |

| Colon transit GC24* | 1.90 | 2.36 ± 0.17 | 2.46 ± 0.10 | 2.56 ± 0.23 | 2.45 ± 0.11 | 2.53 ± 0.17 |

| Colon transit GC48** | 2.96 | 3.31 ± 0.19 | 3.68 ± 0.11 | 3.50 ± 0.21 | 3.65 ± 0.12 | 3.62 ± 0.18 |

| Rectal compliance Pr1/2, mmHg | 7.2 | 13.0 ± 0.9 | 13.5 ± 0.5 | 13.7 ± 1.0 | 12.9 ± 0.5 | 14.6 ± 0.8 |

| VAS mm pain at 36 mmHg | 73 | 57.6 ± 4.7 | 58.1 ± 3.1 | 53.3 ± 6.2 | 60.4 ± 3.4 | 51.6 ± 4.7 |

| VAS mm urge at 36 mmHg | 83.5 | 79.9 ± 2.2 | 76.6 ± 1.9 | 74 5± 5.1 | 74.6 ± 2.4 | 78.4 ± 2.9 |

| Table V-B. Proportion of 160 Participants with Abnormal Sensory Thresholds in Association with Presence or Absence of Frequent Pain and Bloating | ||||||

| Health | Health | IBS | IBS | IBS | IBS | |

| Percent of patients with thresholds below 10th percentile for healthy controls | Pain >6/yr | Pain <6/yr or absent | Pain >6/yr | Pain <6/yr or absent | Bloating YES | Bloating NO |

| Threshold gas, mmHg, % | 0 | 5.4 | 4.4 | 14.3 | 4.0 | 11.1 |

| Threshold urgency, mmHg, % | 50 | 5.4 | 9.9 | 14.4 | 9.5 | 13.3 |

| Threshold pain, mmHg, % | 0 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 0 | 2.7 | 0 |

Tests for main effects of pain (>6 times per year), bloating (no/yes), adjusted for gender and BMI indicate no significant associations detected for transit, satiation, gastric volumes, rectal compliance or sensory ratings of pain or urgency at 36 mmHg distensions.

Association between Number of IBS Symptoms and Gastrointestinal Motor and Sensory Functions

Symptom numbers by disease subgroup is shown in Table VI. The percentages of IBS patients with abnormal colonic transit or increased rectal sensation were respectively 24 and 35% with 1 or 2 symptoms, 63 and 48% with 3 or 4 symptoms, and 8 and 13% with 5 or 6 symptoms. Thus, there is a relationship between 1 to 4 IBS symptoms and abnormal transit and sensation, whereas the patients with 5 or 6 positive symptoms (above average) constituted a lower proportion of those with abnormal motor or sensory findings.

Table VI.

Percentage of Participants in Each Subgroup and the Number of Primary IBS Symptoms Reported Out of a Total of 6 Symptoms (if rows do not reach 100%, it signifies lost or missing data)

| Group | 0 Symptoms | 1 or 2 Symptoms | 3 or 4 Symptoms | 5 or 6 Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls | 76 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| IBS-C | 2 | 23 | 53 | 20 |

| IBS-D | 7 | 32 | 59 | 2 |

| IBS-M | 0 | 31 | 48 | 21 |

Autonomic Function

Table B (see Appendix, on-line) presents a summary of the main autonomic function tests, and these include heart period responses to deep breathing, change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure with assuming upright posture, and lying and standing plasma norepinephrine levels. There were no significant associations with phenotype overall, or among the individual IBS subgroups based on bowel symptoms.

DISCUSSION

In a group of predominantly female patients with IBS evaluated at a tertiary care center, abnormal colonic transit (32%) and rectal hyperalgesia [(20.5%) increased sensory ratings] were the predominant disturbances of physiology, whereas the proportion with rectal hyposensitivity was 16.5%. These observations were based on patients characterized by bowel dysfunction and, particularly, abnormal functions were associated with endorsement of 1 to 4 primary IBS symptoms. In contrast, motor and sensory dysfunctions were not identified in association with frequent pain or bloating or reporting of 5 or 6 primary IBS symptoms.

The psychological disturbances noted in our study, including anxiety, depression scores, somatic symptom scores, positive symptom total, and general severity indices on SCL-90, are consistent with prior reports, suggesting that patients included here were consistent with those published in other reports. The autonomic dysfunctions are unremarkable in this IBS cohort; patients were not selected for autonomic tests based on the presence of symptoms suggestive of dysautonomia in contrast to some earlier studies.

The observations on colonic transit are consistent with small studies in the prior literature using scintigraphy in IBS-D, IBS-C or chronic constipation (2–4). Our study also assessed 29 patients with mixed bowel function and identified overall acceleration of colonic transit, demonstrable at 48 hours in IBS-M. In a recently published paper on transit measurements by Sadik et al., 34% of 70 patients with predominant constipation had delayed colonic transit; whereas, 28% and 7% of 54 patients with predominant diarrhea had accelerated or delayed colonic transit, respectively. Among 57 patients with predominant abdominal pain, 9% and 6% had delayed or accelerated transit, respectively (32).

There was a relatively low prevalence of documented slow colonic transit in IBS (16%) and no significant small bowel transit delay in our patients, reflecting, in part, the large coefficient of variation in small bowel transit (33). Small intestinal motor function has been investigated in smaller studies in the literature from two to four decades ago using laboratory-based or ambulatory methods. The significance of intestinal clusters is unclear, and the study of 74 patients from Gothenburg in 2007 (34) revealed quantitative data that were similar to those published in healthy controls, e.g., number of MMCs per 3 hours, cycle length, duration of MMC. Hence, our findings on small bowel transit are generally consistent with the notion that there are not significant changes in small bowel motor function in IBS.

Rectal Sensation

Some patients with IBS have demonstrable hypersensitivity; however, the proportion with documented hypersensitivity appears lower than that reported by Bouin et al. (8). Our patients appear to manifest hyperalgesia (increased sensory ratings) more often than hypersensitivity to pain (reduced thresholds). The level of the 10th percentile for the pain threshold is 13 mmHg in the present study in contrast to 32 mmHg in the study by Bouin et al. (8).

We consider two general factors may contribute to the discrepancy between our study and others in the literature: definition and methodological and psychological status of IBS participants.

(a) Differences in definitions suggest that caution is required in comparing results reporting hypersensitivity in different laboratories. In our study, the threshold for pain was defined as the first pressure that was associated with experience of pain, and all studies were performed over a 3-year period by one technologist (IB). The term “threshold” is defined as “the point at which a physiological or psychological effect begins to be produced” (Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary), and we have applied this definition in several studies in the literature (35,36). In contrast, other papers in the literature defined “threshold” as grade 3/5 on the pain scale (37,38) or 3/10 on the discomfort scale (8) for the individual patient. These definitions combine elements of threshold and sensory rating. There are also differences in distensions applied during ascending method of limits.

b. Differences in methodology for sensation studies - There are also significant differences in the distension methods used to study sensation. Different laboratories apply either a step-wise ramp of pressures at steps of 2 or 4 mm Hg, or a series of increasing phasic distensions starting from zero pressure for each step. Lembo et al. showed that 60% of 50 patients with IBS were hypersensitive for discomfort during phasic distention, whereas only 4% were hypersensitive during ramp distention (39). This may explain why IBS patients did not exhibit hypersensitivity by thresholds in response to ramp distension relative to healthy controls in our studies. We do not use the tracking or random double staircase method to identify the threshold pressures in our studies, since at least two groups (40,41) showed that tracking and more complex protocols do not significantly alter the estimated threshold, and tracking typically involves about 20 balloon distensions after the subject’s pain threshold is estimated in the ascending method of limits. Increasing the number of interrogations about sensations, may introduce bias or errors in a fatigued and stressed or disinterested participant. Our application of ascending method of limits requires 12 distensions and interrogations, whereas tracking and random double staircase leads to >40 distensions.

c. Inter-study consistency of reported rectal hypersensitivity - Naliboff et al. reported that perceptual ratings for rectal sensation to 45 and 60 mmHg distensions in 20 IBS patients normalized when followed over a 12-month period, whereas IBS symptom severity did not (42). These data suggest that sensation may not be a ubiquitous or consistent finding in IBS. After repetitive sigmoid stimulation (a maneuver intended to further sensitize the visceral afferents), Lembo et al. reported that the discomfort threshold during rectal distension was decreased only in patients whose predominant symptom was pain, not bloating (43).

Posserud et al. (44) reported that only 39% of their IBS patients had hypersensitivity to either pain or discomfort by thresholds. By including the proportion with unpleasantness rating and viscerosomatic referral, the total number of IBS patients with heightened visceral sensation was 61%. They observed that hypersensitivity was related to symptom severity based on 7 point Likert scales of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale.

The literature also records hyposensitivity for discomfort in IBS-C (45). Gladman et al. (46) reviewed the literature and proposed the mechanism may reflect megarectum or reduced afferent function. We confirmed that 16.5% of the IBS patients had reduced rectal sensation; and IBS-C had somewhat reduced sensation of urgency. There were no differences in rectal compliance in these patients. Severe sexual/physical abuse appears to be associated with reduced rectal sensation (40), despite greater pain reporting and poorer health status in IBS patients with abuse history.

d. Differences in proportion of females - Our study included only female healthy volunteers; while this differs from data in other studies (7,8,23,43,44), this gender bias reflected the IBS patients recruited.

e. Psychological status - Dorn et al. reported on 121 IBS patients and 28 controls. IBS patients had lower colonic pain thresholds, but similar neurosensitivity and a greater tendency to report pain and increased somatization (47), suggesting IBS is strongly influenced by a psychological tendency to report pain and urge, rather than increased neurosensory sensitivity. We did not confirm an association between increased rectal sensations and indices of somatization on the SCL-90 or the somatic symptom score of the BDQ. However, the spectrum of SCL-90 measurements in our patients at Mayo Clinic are on average 5 points lower than those of patients evaluated with the same domains (anxiety, depression, somatization) by brief symptom inventory in patients at University of North Carolina (47). In contrast, controls in the two centers show virtually identical mean scores for anxiety, depression and somatization. The lack of an association between sensory parameters and psychological domains may reflect the lower psychological disturbances in the patients at Mayo Clinic.

In summary, given that hypersensitivity is not observed in all studies, is not consistent over time, has a variable association with symptoms, and may reflect psychological propensity to report pain rather than up-regulated visceral afferent function, our data question whether rectal hypersensitivity is a biological marker of IBS.

Dyspepsia and Gastric Function in IBS

This study also comprehensively addressed the function of the stomach in IBS patients, since epidemiological studies suggest 30–80% of patients with IBS have upper abdominal pain or discomfort (19,20), the symptom phenotype changes over time (48), and scintigraphic studies show accelerated gastric emptying in patients with functional (symptomatic, chronic) diarrhea (49). In this group of IBS patients, 30% had upper abdominal pain aggravated by food intake, consistent with the study of Talley et al. (19). However, we did not identify significant abnormalities of motility or sensation of the stomach, except for a reduced accommodation volume after a standard small meal in those with the most significant pain precipitated by food and persisting for 2 hours after the meal. As shown by Castillo et al. (50) in a community cohort of dyspeptics, somatization and general severity index on SCL-90 was associated with food-related dyspepsia rather than abnormal sensation or motility.

Strengths and Limitations

Among the strengths in our study is the comprehensive spectrum of physiological measurements conducted using state-of-the-art and validated methods. All sensation studies were conducted by one technologist with considerable experience, and both thresholds and sensory ratings were identified to comprehensively assess the relative contributions of sensation and motor functions based on different symptom phenotypes in IBS.

A limitation of our rectal sensation analysis is that we used the 10–90th percentile to define the range for the healthy volunteers. This was determined in view of the number of healthy controls numbering 40. If we had used the usual 5th–95th percentile, the number of IBS patients with evidence of increased rectal sensation would have been even lower. Our healthy subjects, who did not endorse symptoms of IBS on a validated questionnaire, appeared to be quite sensitive on rectal sensation testing. One possible explanation is that 12.2% were taking an SSRI for depression, not for IBS. By protocol, we had permitted SSRI use in healthy subjects to avoid a potential imbalance in SSRI use and the alternative criticism that any differences between IBS and controls would be attributable to the use of SSRI. However, the proportion of healthy participants taking SSRI (12.2%) appears too small to account for the high sensation scores in healthy volunteers in our study.

Other limitations are, since the study involved predominantly females, the data presented here may not be generalizable to men, and we studied the relationship between physiological endpoints and number of symptoms, rather than symptom severity.

Whereas the study is conducted at a tertiary referral center, the cohort consisted of patients residing within 200 miles of that center, and the levels of somatization, anxiety, depression and concomitant functional dyspepsia were consistent with those of other IBS patients in the literature. Moreover, when we compare the degree of somatization, anxiety and depression on SCL-90 (31) to the same domains in the comparable Brief Symptom Inventory (51) evaluated at the University of North Carolina, the scores were on average 5 points lower in the patients in our study at Mayo Clinic.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in a group of mostly women with IBS, colonic transit is the most prevalent physiological abnormality (32%) and it is somewhat more frequent than increased rectal sensation. Among those 20.5% with increased sensation, hypersensitivity (7.6%) was less often demonstrated than hyperalgesia (13%). Given the ability to document the abnormal transit with a low risk, validated, noninvasive test such as scintigraphy (32,34,52,53), in contrast to the more invasive and technically more demanding sensory tests, these data support the use of transit assessments which may help select patients for pharmacologically directed therapy (e.g., prokinetic) and, thus, optimize therapeutic benefit in clinical and research settings. Such evaluations of transit and sensation may also enhance the selection of patients for participation in drug trials in irritable bowel syndrome.

Supplementary Material

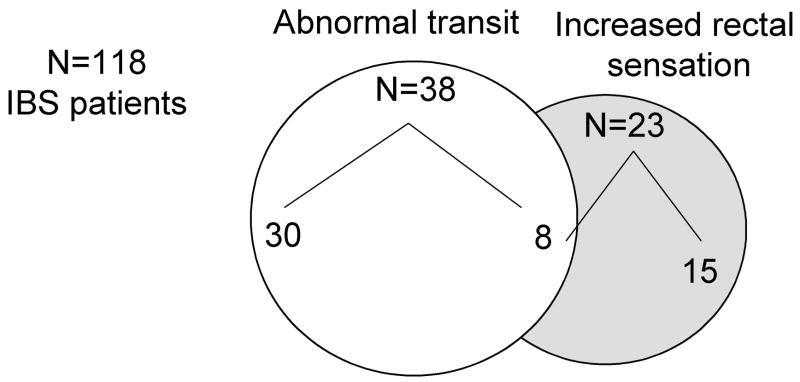

Figure 5.

Overlap of abnormal transit and increased sensation in patients with IBS.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by grants RO1-DK54681 and K24-DK02638 to Dr. Camilleri from National Institutes of Health. Dr. Low is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants NS32352, NS44233, NS22352, and NS43364, by Mayo CTSA grant MO1-RR00585, and by Mayo funds. The studies were conducted in the Mayo Clinical Research Unit which is supported by NIH grant RR024150. The excellent secretarial support of Mrs. Cindy Stanislav is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations used

- BDQ

bowel disease questionnaire

- BMI

body mass index

- BOP

baseline operating pressure

- GV

gastric volume

- HAD

Hospital Anxiety and Depression

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- IBS-C

constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome

- IBS-D

diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome

- IBS-M

mixed irritable bowel syndrome

- SCL

symptom checklist

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- VAS

visual analog scale

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Michael Camilleri, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A

Sanna McKinzie, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A

Irene Busciglio, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A.

Phillip A. Low, Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A

Seth Sweetser, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A

Duane Burton, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A.

Kari Baxter, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A.

Michael Ryks, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (CENTER), College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A.

Alan R. Zinsmeister, Department of Health Sciences Research, Division of Biostatistics, College of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A

References

- 1.Camilleri M. Mechanisms in IBS: something old, something new, something borrowed. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cann PA, Read NW, Brown C, Hobson N, Holdsworth CD. Irritable bowel syndrome: relationship of disorders in the transit of a single solid meal to symptom patterns. Gut. 1983;24:405–411. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.5.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vassallo M, Camilleri M, Phillips SF, Brown ML, Chapman NJ, Thomforde GM. Transit through the proximal colon influences stool weight in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:102–108. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stivland T, Camilleri M, Vassallo M, Proano M, Rath D, Brown M, Thomforde G, Pemberton J, Phillips S. Scintigraphic measurement of regional gut transit in idiopathic constipation. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:107–115. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi MG, Camilleri M, O’Brien MD, Kammer PP, Hanson RB. A pilot study of motility and tone of the left colon in patients with diarrhea due to functional disorders and dysautonomia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien MD, Camilleri M, von der Ohe MR, Phillips SF, Pemberton JH, Prather CM, Wiste JA, Hanson RB. Motility and tone of the left colon in constipation: a role in clinical practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2532–2538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mertz H, Naliboff B, Munakata J, Niazi N, Mayer EA. Altered rectal perception is a biological marker of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:40–52. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouin M, Plourde V, Boivin M, Riberdy M, Lupien F, Laganiere M, Verrier P, Poitras P. Rectal distention testing in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of pain sensory thresholds. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1771–1777. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mertz H, Morgan V, Tanner G, Pickens D, Price R, Shyr Y, Kessler R. Regional cerebral activation in irritable bowel syndrome and control subjects with painful and nonpainful rectal distention. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:842–848. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Craig AD. Neuroimaging of the brain-gut axis: from basic understanding to treatment of functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1925–1942. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunlop SP, Coleman NS, Blackshaw E, Perkins AC, Singh G, Marsden CA, Spiller RC. Abnormalities of 5-hydroxytryptamine metabolism in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunlop SP, Hebden J, Campbell E, Naesdal J, Olbe L, Perkins AC, Spiller RC. Abnormal intestinal permeability in subgroups of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1288–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkinson W, Lockhart S, Whorwell PJ, Keevil B, Houghton LA. Altered 5-hydroxytryptamine signaling in patients with constipation- and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:34–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwee KA, Graham JC, McKendrick MW, Collins SM, Marshall JS, Walters SJ, Read NW. Psychometric scores and persistence of irritable bowel after infectious diarrhoea. Lancet. 1996;347:150–153. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbara G, Wang B, Stanghellini V, de Giorgio R, Cremon C, Di Nardo G, Trevisani M, Campi B, Geppetti P, Tonini M, Bunnett NW, Grundy D, Corinaldesi R. Mast cell-dependent excitation of visceral-nociceptive sensory neurons in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:26–37. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chadwick VS, Chen W, Shu D, Paulus B, Bethwaite P, Tie A, Wilson I. Activation of the mucosal immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1778–1783. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gwee KA, Collins SM, Read NW, Rajnakova A, Deng Y, Graham JC, McKendrick MW, Moochhala SM. Increased rectal mucosal expression of interleukin 1beta in recently acquired post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:523–526. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmen N, Isaksson S, Simren M, Sjovall H, Ohman L. CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJ., 3rd Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1259–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Nyren O, Tibblin G. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zighelboim J, Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Visceral perception in irritable bowel syndrome. Rectal and gastric responses to distension and serotonin type 3 antagonism. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:819–827. doi: 10.1007/BF02064986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trimble KC, Farouk R, Pryde A, Douglas S, Heading RC. Heightened visceral sensation in functional gastrointestinal disease is not site-specific. Evidence for a generalized disorder of gut sensitivity. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1607–1613. doi: 10.1007/BF02212678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouin M, Lupien F, Riberdy M, Boivin M, Plourde V, Poitras P. Intolerance to visceral distension in functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome: an organ specific defect or a pan intestinal dysregulation? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:311–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drossman DA, Morris CB, Hu Y, Toner BB, Diamant N, Leserman J, Shetzline M, Dalton C, Bangdiwala SI. A prospective assessment of bowel habit in irritable bowel syndrome in women: defining an alternator. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:580–589. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aggarwal A, Cutts TF, Abell TL, Cardoso S, Familoni B, Bremer J, Karas J. Predominant symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome correlate with specific autonomic nervous system abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:945–950. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heitkemper M, Burr RL, Jarrett M, Hertig V, Lustyk MK, Bond EF. Evidence for autonomic nervous system imbalance in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2093–2098. doi: 10.1023/a:1018871617483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tillisch K, Mayer EA, Labus JS, Stains J, Chang L, Naliboff BD. Sex specific alterations in autonomic function among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2005;54:1396–1401. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.058685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45:II43–47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1456–1479. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale--preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9:13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadik R, Stotzer PO, Simrén M, Abrahamsson H. Gastrointestinal transit abnormalities are frequently detected in patients with unexplained GI symptoms at a tertiary centre. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007 Nov 12; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01025.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cremonini F, Mullan BP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Rank MR. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic transit measurements for studies of experimental therapies. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2002;16:1781–1790. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Posserud I, Stotzer PO, Bjornsson ES, Abrahamsson H, Simren M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2007;56:802–808. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Hanson RB. Adrenergic modulation of human colonic motor and sensory function. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G997–G1006. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.5.G997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delgado-Aros S, Chial HJ, Camilleri M, Szarka LA, Weber FT, Jacob J, Ferber I, McKinzie S, Burton DD, Zinsmeister AR. Effects of a kappa-opioid agonist, asimadoline, on satiation and GI motor and sensory functions in humans. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:G558–G566. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00360.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitehead WE, Delvaux M The Working Team of Glaxo-Wellcome Research, UK. Standardization of barostat procedures for testing smooth muscle tone and sensory thresholds in the gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:223–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1018885028501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delvaux M, Beck A, Jacob J, Bouzamondo H, Weber FT, Frexinos J. Effect of asimadoline, a kappa opioid agonist, on pain induced by colonic distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lembo T, Munakata J, Mertz H, Niazi N, Kodner A, Nikas V, Mayer EA. Evidence for the hypersensitivity of lumbar splanchnic afferents in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1686–1696. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90809-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ringel Y, Whitehead WE, Toner BB, Diamant NE, Hu Y, Jia H, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA. Sexual and physical abuse are not associated with rectal hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2004;53:838–842. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.021725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanc C, Delvaux M, Maillot C, Bouin M, Lagier E, Fioramonti J, Buéno L, Frexinos J. Distension protocols for evaluation of rectal sensitivity: The simplest, the best? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:A722. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naliboff BD, Berman S, Suyenobu B, Labus JS, Chang L, Stains J, Mandelkern MA, Mayer EA. Longitudinal change in perceptual and brain activation response to visceral stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:352–365. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lembo T, Naliboff B, Munakata J, Fullerton S, Saba L, Tung S, Schmulson M, Mayer EA. Symptoms and visceral perception in patients with pain-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1320–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Posserud I, Syrous A, Lindström L, Tack J, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Altered rectal perception in irritable bowel syndrome is associated with symptom severity. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1113–1123. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prior A, Maxton DG, Whorwell PJ. Anorectal manometry in irritable bowel syndrome: differences between diarrhoea and constipation predominant subjects. Gut. 1990;31:458–462. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.4.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gladman MA, Lunniss PJ, Scott SM, Swash M. Rectal hyposensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1140–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorn SD, Palsson OS, Thiwan SI, Clark WC, Kanazawa M, van Tilburg, Drossman DA, Scarlett Y, Levy RL, Ringel Y, Crowell MD, Olden KW, Whitehead WE. Increased colonic pain sensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome is the result of an increased tendency to report pain rather than increased neurosensory sensitivity. Gut. 2007;56:1202–1209. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.117390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;15:165–177. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charles F, Phillips SF, Camilleri M, Thomforde GM. Rapid gastric emptying in patients with functional diarrhea. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:323–328. doi: 10.4065/72.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castillo EJ, Camilleri M, Locke GR, Burton DD, Stephens DA, Geno DM, Zinsmeister AR. A community-based, controlled study of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:985–996. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00454-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burton DD, Camilleri M, Mullan BP, Forstrom LA, Hung JC. Colonic transit scintigraphy labeled activated charcoal compared with ion exchange pellets. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1807–1810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR. Towards a relatively inexpensive, noninvasive, accurate test for colonic motility disorders. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:36–42. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91092-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.