Abstract

Background

The accurate measurement of body composition changes is important when evaluating the efficacy of medical nutrition therapy and weight management programs, yet is not well documented in older women.

Objective

We compared methods of estimating energy-restriction-induced body composition changes in postmenopausal women. Design: 27 women (59 ± 8 y; BMI 29.0 ± 2.9 kg/m2; mean ± SD) completed a 9-wk energy restriction period (5233 kJ/d, (1250 kcal/d)). Changes in % body fat (Δ%BF), fat mass (ΔFM), and fat-free mass (ΔFFM) were measured by hydrostatic weighing (HW), air-displacement plethysmography (ADP), dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), and deuterium oxide dilution (D2O). The Baumgartner et al. (Am J Clin Nutr 53:1345−1353, 1991) four-compartment (4C) model with body volume from HW was the criterion method. The 4C model with body volume from ADP was also compared. Regression equations were developed based on 4CHW (dependent variable) utilizing results of change (POST-PRE) for each method.

Results

The women lost 6.8 ± 3.2 kg; 9% of baseline weight. Based on 4CHW, the body composition changes were −2.4 ± 4.5 Δ%BF, −4.7 ± 3.3 kg ΔFM, and −2.6 ± 4.4 kg ΔFFM. No differences were detected by ANOVA for Δ%BF, ΔFM, and ΔFFM among 4CHW, HW, ADP, DXA, D2O, and 4CADP. Bland-Altman limits of agreement showed differences between methods that ranged from 14.5 to −14.1 Δ%BF, 7.8 to −8.1 kg ΔFM, and 7.5 to −8.4 kg ΔFFM for individuals. A bias was shown with 4CADP overestimating Δ%BF (1.4 %) and FM (0.6 kg) and underestimating ΔFFM (−1.2 kg) compared to 4CHW. The regression model was acceptable for %BF (4CADP, 2CHW, and 2CD2O); FM and FFM (4CADP, 3CDXA, 2CHW, and 2CD2O), but not for other estimates of %BF, FM, FFM.

Conclusions

These body composition assessment methods may be used interchangeably to quantify changes in % body fat, fat mass, and fat-free mass with weight loss in groups of postmenopausal women. 4CADP overestimates Δ%BF and underestimates ΔFFM. When utilizing one of these comparison methods (4CADP, 3CDXA, 2CHW, 2CD2O) to quantify changes in fat mass and fat-free mass for an individual postmenopausal woman, regression equations may be used to relate the data to 4CHW.

Keywords: Hydrostatic weighing, air-displacement plethysmography, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, total body water, deuterium oxide dilution, 4-compartment model

Introduction

The ability of researchers and health professionals to accurately estimate changes in body composition is critical in determining the effectiveness of medical nutritional therapy and changes that occur with weight management programs. Researchers, health professionals and the public may benefit from technological advances that have increased available options for estimating changes in % body fat (Δ%BF), fat mass (ΔFM), and fat-free mass (ΔFFM). Hydrostatic weighing (HW) has been a long standing criterion method of determining body density (1). Hydrostatic weighing estimates body composition based on a 2-compartment (2C) model in which body weight is equal to the sum of FM and FFM. However, the use of HW is often confined to a research setting. Both air-displacement plethysmography (ADP) (2), another method also based on a 2C model and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), a method based on a 3-compartment (3C) model (3), (FM plus FFM (sum of lean tissue mass and total body bone mineral)) are increasingly available in health and fitness facilities.

The 2C or 3C (DXA) models may not accurately estimate changes in body composition due to energy restriction in overweight postmenopausal women (4, 5). Both models (6) assume the densities of FM (0.9007 g/cm3), FFM (1.1000 g/cm3) (DFFM), and water content of FFM (73.2%) remain constant with aging, obesity and changes in body mass (4). Since these assumptions of density are based on early analysis of male cadavers (4), they provide potentially significant sources of error when calculating body composition because age, race, gender, level of body fatness and changes in body weight can influence fat-free compartments (protein, water, mineral) (5, 7-15). Nevertheless, Visser et al. (16) determined that most of the variability in DFFM was accounted for by total body water (TBW) with only minor contributions from age, race, and gender. Visser et al. concluded that the assumption of constant DFFM is valid in black, elderly and obese subjects, but observed a tendency for a lower DFFM in older, white women.

The influence of weight loss on the assumed DFFM is less well studied and documented. Researchers have found an increase in TBW:FFM with weight loss (5, 7, 13). This could be due to changes in TBW (13) and bone mineral content (BMC), which may (13-15, 17) or may not (5, 18-20) decrease with weight reduction. Thus, variability in DFFM may result in errors in estimating FFM, and therefore %BF and FM, which would limit use of a 2C or 3C model (6).

Given the apparent possible assumption violations for the 2C and 3C models (DXA), a 4-compartment (4C) model has been suggested as the best in vivo body composition model available (16, 21, 22). The 4C molecular model reduces the potential for assumption errors by utilizing independent estimates of four components (FM, BMC, TBW and protein mass). This 4C model was developed specific to the use of HW for measuring body volume (BV). The development of ADP for measurement of BV led researchers to investigate whether BVADP may be substituted for BVHW in the 4C model using various populations. While both utilize densitometry via the Siri equation to obtain %BF, they differ in methods used to obtain body volume (residual lung volume, 4CHW, vs. thoracic lung volumne, 4CADP). Recently, investigators found small, but significant differences in BV and density and a trend toward significant differences between 4C model estimates of %BF (23).

Researchers have yet to present data comparing changes in body composition assessment using 2CHW, 2CADP, 3CDXA, TBW using the deuterium oxide (D2O) dilution technique (2C), and 4CADP against 4CHW in overweight and obese postmenopausal women with energy restriction. Therefore, uncertainty exists about whether mean estimates of Δ%BF, ΔFM and ΔFFM among these methods would agree and provide interchangeable measurements of body composition. Reporting of regression analyses, R2, SEE and Bland Altman analyses has been recommended (24) to aid with understanding of the relationship between methods. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the interchangeability of 2C-, 3C- and 4CADP models of body composition using the 4CHW model as the criterion method for estimates of Δ%BF, ΔFM and ΔFFM in postmenopausal, overweight and obese women following energy restriction.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

The subjects for this study were 27 overweight and mildly obese, postmenopausal women (59 ± 8 y; BMI 29.0 ± 2.9 kg/m2, see Table 1). This group of women was a subset of women who completed a 9-wk energy restriction weight loss protocol (described below). The primary aim of the parent study was to assess the effects of the macronutrient distribution and source of dietary protein on changes in weight and body composition with energy restriction. The Purdue University Committee on the Use of Human Research Subjects approved the protocol, and informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to enrollment in the study. Phone screening was conducted to determine if a potential subject met basic eligibility criteria which included: nonsmoker, age ≥ 50 y, ≥ 2 y postmenopausal (self-reported based on last menstruation), and body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 and ≤ 34 kg/m2 at the time of screening. Potential subjects attended a medical screening visit and completed diet history questionnaires. The medical screening consisted of a written medical history, measurements of height (shoes removed), weight (nude, with weighed robe) on electronic scale, blood pressure, resting electrocardiogram, and clinical blood and urine chemistries. Medical history and screening data for all subjects were reviewed by the study physician prior to enrollment in the study. Subjects needed to be willing to discontinue use of all nutritional supplements (except calcium, due to recruitment difficulties), nonprescription medications and alcohol three weeks prior to starting and throughout the study period. All subjects received a monetary stipend.

Table 1.

| Baseline | Post | Change (Δ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 59 ± 8 | ||

| Height (m) | 1.64 ± 0.05 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 76.9 ± 10.2 | 70.1 ± 10.6 | −6.8 ± 3.23 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.0 ± 2.9 | 26.1 ± 3.5 | −2.9 ± 3.13 |

| BVHW (L) | 76.6 ± 10.3 | 70.2 ± 11.3 | −6.4 ± 3.63 |

| BVADP (L) | 77.2 ± 10.5 | 70.0 ± 11.1 | −7.2 ± 3.23 |

| Db (HW) (g/L) | 1.011 ± 0.0124 | 1.016 ± 0.014 | 0.005 ± 0.0113 |

| Db (ADP) (g/L) | 1.003 ± 0.0104 | 1.009 ± 0.011 | 0.006 ± 0.0075 |

| TBW (kg) | 32.3 ± 3.4 | 30.6 ± 4.0 | −1.7 ± 2.73 |

| TBW/FFM4C HW (%) | 72.9 ± 3.4 | 73.2 ± 6.4 | 0.3 ± 0.05 |

| BMC (kg) | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| BMC/FFM4C HW (%) | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.65 |

Mean ± SD, BMI, body mass index; Db (HW), body density measured by hydrostatic weighing; Db (ADP), body density measured by air-displacement plethysmography; BV, body volume; TBW, total body water; FFM, fat-free mass; BMC, bone mineral content; BMD, bone mineral density;

n=27;

P < 0.05, paired t-test;

P < 0.05, t-test;

P < 0.01, paired t-test

Experimental design

This 11-wk study included a 2-wk baseline-testing period (no dietary control), followed immediately by a 9-wk period of energy-restriction-induced weight loss, with testing repeated during the 9th wk of intervention. Subjects were assigned to one of four groups; three energy restriction groups consumed a lacto-ovo vegetarian basal diet (4186 kJ/d (1000 kcal/d)) plus 1047 kJ/d (250 kcal/d) of beef (48% carbohydrate (CHO), 26% protein (PRO), 26% fat (FAT) of total energy intake), or chicken (48% CHO: 26% PRO: 26% FAT), or carbohydrate/fat snack foods (58% CHO: 16% PRO: 26% FAT), and a control group was instructed to follow their habitual diet and to maintain body weight. All subjects were asked to maintain their usual levels of physical activity and to not begin any type of exercise program.

Fifty-seven Caucasian women started the diet intervention period. During the intervention period one subject dropped out for personal reasons, another subject was dismissed due to her need to start new medication, and one subject dropped out due to an unwillingness to adhere to the diet. Fifty-four women completed the study. The data from the control group (n=11) were excluded from these analyses since this group did not change body weight. We were unable to obtain residual lung volume measurements on all of the subjects due to technical difficulties with the equipment and because the procedure was uncomfortable for some of the women (n=10). Data from six women were excluded because they were unable to provide sufficient urine volume required for D2O analysis. After excluding these subjects, data from 27 women were used for analyses.

Body Composition Assessment Procedures

Subjects were instructed to drink about 1400 mL (six 8-oz glasses) of water the day before testing. They were instructed to drink about 240 mL of water the morning of testing prior to arriving at the laboratory. Each subject arrived at the laboratory in the early morning after an overnight 12-h fast. Each subject was not permitted to consume food or water during testing and wore a tight fitting bathing suit for HW and ADP testing, and a bathing cap for ADP testing. All jewelry was removed. Testing was conducted in the following order: DXA, ADP and then HW, and completed within a two-hour period to control for diurnal changes in body composition.

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

Wearing street clothing free of metal and/or plastic, each subject remained motionless in the supine position for 5−10 minutes, and was scanned on standard or thick mode based on subject size with a total body scanner (GE Medical Systems/LUNAR Prodigy™, Madison, WI). Prodigy software (version 6.7) was used to calculate the ratio of soft tissue (fat and fat-free) at the two energies measured (25) based on a 3C model in which BMC and bone-free soft tissue attenuated energy from the x-ray in a tissue specific manner. FFM was calculated as the sum of lean tissue plus BMC (CV = 1.7%). %BF is equal to FM divided by body weight (x 100). The same technician performed all analyses. Analyzing a phantom spine provided by the company assessed quality assurance, and daily calibrations were performed before all scans using a calibration block provided by the manufacturer. The coefficient of variation for percent fat from repeated scans on a group of 20 men and women ranging from 9% to 50% fat in our laboratory was 1.9%.

Air-displacement plethysmography

Air-displacement plethysmography was utilized to measure raw BV as previously described (2) using the Bod Pod® Body Composition System (Life Measurement, Inc., Concord, CA). Triplicate trials were performed on each subject. Before each trial the machine was calibrated using a precision 50 liter cylinder provided by the manufacturer. Each subject's thoracic lung volume was measured during normal breathing using a tube connected to the ADP breathing circuit system as described elsewhere (2). The 2C Siri equation (6) was used to estimate %BF after Db was obtained. FFM was calculated as body mass minus FM. The CV for between week %BF in our laboratory using 37 men and women ranging from 9% to 50% BF was 4.0%.

Hydrostatic weighing

Hydrostatic weighing was used to measure BV as previously described (26) (Exertech® Body Density Measurement System, Dresbach, MN). Prior to each session the weighing platform located inside the stainless steel water tank was calibrated with a 7.82 kg metal bar, as specified by the equipment manufacturer. An additional 4.5 kg weight belt was tared and used to assist the subjects with submersion. Subjects sat or kneeled completely submerged underwater on the weighing platform and were instructed to maximally exhale air. A total of 8−10 replicate trials were performed in the underwater weighing tank with each subject. Values from the three heaviest trials were averaged to obtain body mass in water. The 2C Siri equation (6) was used to estimate %BF after Db was obtained. FFM was calculated as body mass minus FM. Residual lung volume (air remaining in the lungs after maximal exhalation) was measured outside the tank using an open circuit oxygen-dilution technique (Vmax 229 series, SensorMedics Corp. Yorba Linda, CA). The CV for between week %BF in our laboratory using seven postmenopausal women ranging from 31% to 53%BF was 3.7%.

Deuterium oxide dilution

Total body water was determined using D2O as previously described (27, 28). Upon arrival at the laboratory a baseline urine sample was obtained and then each subject consumed orally a 20-g dose of D2O. Urine samples were again collected at 2, 3 and 4 hours following the dose. Subjects reached plateau for isotope dilution by the 3rd hour as demonstrated by no significant difference in D2O content between the 3rd and 4th hour samples, p = 0.46. Urine volume was measured and an aliquot was stored at −20°C. The D2O concentration of the urine samples was determined using an Infrared Spectrophotometer 360 Water System (Nicolet Instrument Corp., Waltham, Mass.) (28). Total body water is based on mass balance and was calculated using a dilution principle (with corrections made for losses of isotope in urine). Calculations were used to obtain total isotope dilution (27). Total body water and FFM were calculated with the following formulas:

TBW = Calculated total isotope dilution / 1.04 (correction for exchange of isotope with nonaqueous hydrogen during equilibration in vivo).

FFM (kg) = TBW (L) / 0.732 (hydration constant)

TBW estimates FM based on body mass minus FFM. %BF was calculated as (FM/body weight X 100). The CV for between week %BF in our laboratory using 23 women ranging from 24% to 51%BF was 4.6%. The 0.732 hydration constant was the value originally used by Scholerb (27), which was adopted from guinea pig data. Our confidence using this number is supported by the results from 18 studies that determined the hydration of fat-free mass by chemical analysis of whole nonruminant animals (including three studies in humans) (29). The mean (±SD) fractional hydration of fat-free mass among the 18 studies was 0.731 ± 0.013, and 0.731 among the three human studies.

Compartment model

The 4C model with BV from HW of Baumgartner et al. (9) served as the criterion model. Body volume from ADP was substituted for BV from HW and provided a second 4C model using the same equation. This 4C model requires measurement of BV, TBW, BMC and body weight (BW) to calculate FM:

FM = [(2.75 × BV) – (0.714 × TBW) + (1.148 × TBBM) – (2.05 × BW)]

To obtain total body bone mineral (TBBM) an adjustment for the ratio of osseous to nonosseous mineral and loss of mineral during ashing of bone (9) was calculated as follows:

TBBM (g) = BMC × 1.279 To obtain percent body fat and FFM:

%BF = FM / BW FFM = BW minus FM

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA to assess the main effects of diet group (between-subject factor) and measurement method (within-subject factor). These analyses established that there were no differential body composition responses to the energy restriction among the three diet groups. A paired t-test was used to compare subject characteristics in Table 1 (except for age and height) at PRE and PRE vs. POST. The relationship between the criterion method (4CHW) and the comparison method single differences (Δ), was established using regression analyses.

The Bland-Altman statistical test was used to examine the likelihood of a comparison method agreeing to a criterion method. This procedure examined bias (mean difference) between the two methods and if the difference was related to the magnitude of the change. The standard deviation of the delta difference (ΔΔ) (single difference (Δ) 4CHW minus single difference (Δ) comparison method) was examined and limits of agreement obtained. The bias was examined using paired t-tests. Bland-Altman tests were conducted using ANALYSE-IT Software, LTD version 1.71 (ANALYSE-IT Software, LTD, Leeds, England). ANOVA and paired t-tests were conducted using SPSS statistical software version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A P level of < 0.05 was used for all significance testing. All values are reported as mean ±SD unless otherwise noted.

Results

Body composition

Body weight and BMI decreased with energy restriction, P < 0.01 (Table 1). Changes in body weight measured by 3CDXA were not significantly different from weight measured by the 2CADP scale (−6.9 ± 2.9 kg, vs. −6.8 ± 3.2 kg, r = 0.98, P < 0.0001). Body volume decreased and Db increased with energy restriction. Db measured by 2CHW and 2CADP were significantly different at baseline, P < 0.1. Changes in BV and Db measured by 2CHW were not significantly different from changes measured by 2CADP, P = 0.23, P = 0.37, respectively. Total body water was lower after energy restriction, P < 0.01, but TBW: FFM was not different. BMC did not change due to energy restriction, however, BMC: FFM increased after energy restriction, P < 0.01.

Body composition methods comparison

Table 2 presents the single difference (POST-PRE) for each method. There were no differences in mean Δ%BF, ΔFM and ΔFFM among the 6 methods: 4CHW, 4CADP, 3CDXA, 2CHW, 2CADP, and 2CD20.

Table 2.

Results of body composition changes (single difference) due to energy restriction in postmenopausal women

| Method/Model | PRE | POST | Single difference POST- PRE (Δ) | Confidence Interval (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % BODY FAT | ||||

| 4CHW | 41.5 ± 5.4 | 39.1 ± 6.5 | −2.4 ± 4.5 | 6.4 to −11.1 |

| 4CADP | 43.6 ± 4.9 | 39.9 ± 5.5 | −3.7 ± 3.0 | 2.1 to −9.6 |

| 3CDXA | 43.0 ± 4.8 | 40.1 ± 5.7 | −2.9 ± 1.9 | 0.8 to −6.6 |

| 2CHW | 39.3 ± 5.8 | 37.1 ± 6.8 | −2.2 ± 5.3 | 8.3 to −12.6 |

| 2CADP | 43.5 ± 5.4 | 40.8 ± 5.7 | −2.7 ± 2.7 | 2.6 to −8.0 |

| 2CD2O | 42.3 ± 5.5 | 40.0 ± 5.8 | −2.3 ± 4.8 | 7.0 to −11.6 |

| FAT MASS (kg) | ||||

| 4CHW | 32.0 ± 7.5 | 27.3 ± 6.6 | −4.7 ± 3.3 | 1.6 to −11.1 |

| 4CADP | 33.8 ± 7.5 | 28.3 ± 7.4 | −5.5 ± 2.7 | 0.2 to 10.8 |

| 3CDXA | 33.4 ± 7.7 | 28.6 ± 8.1 | −4.8 ± 2.3 | −0.3 to −9.4 |

| 2CHW | 30.6 ± 7.8 | 26.2 ± 7.5 | −4.4 ± 4.8 | 5.0 to −13.8 |

| 2CADP | 34.0 ± 7.8 | 29.0 ± 8.0 | −5.0 ± 3.1 | 1.1 to −11.1 |

| 2CD2O | 32.9 ± 7.6 | 28.3 ± 7.6 | −4.6 ± 4.0 | 3.3 to −12.5 |

| FAT-FREE MASS (kg) | ||||

| 4CHW | 44.4 ± 4.5 | 42.0 ± 6.2 | −2.6 ± 4.4 | 4.9 to −9.9 |

| 4CADP | 43.0 ± 4.2 | 41.9 ± 5.2 | −1.1 ± 2.8 | 4.4 to −6.6 |

| 3CDXA | 43.5 ± 3.6 | 41.5 ± 3.6 | −2.0 ± 1.0 | 0.1 to −4.0 |

| 2CHW | 46.2 ± 4.8 | 44.3 ± 5.4 | −1.9 ± 5.3 | 8.6 to −12.3 |

| 2CADP | 42.9 ± 4.1 | 41.0 ± 4.4 | −1.9 ± 1.0 | 0.1 to −3.9 |

| 2CD2O | 44.1 ± 4.6 | 41.8 ± 5.5 | −2.3 ± 3.7 | 5.0 to −9.6 |

Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise noted; significant differences were not found among the methods using ANOVA. 4CHW = 4-compartment model using hydrostatic weighing for body volume, 4CADP = 4-compartment model using air-displacement plethysmography for body volume, 3CDXA, 3-compartment model dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, 2CHW= 2-compartment model hydrostatic weighing, 2CADP= 2-compartment model air-displacement plethysmography, 2CD2O = 2-compartment model deuterium oxide dilution technique for measurement of total body water

In general Bland-Altman analyses showed very large differences between 4CHW and other methods for Δ%BF, ΔFM and ΔFFM.

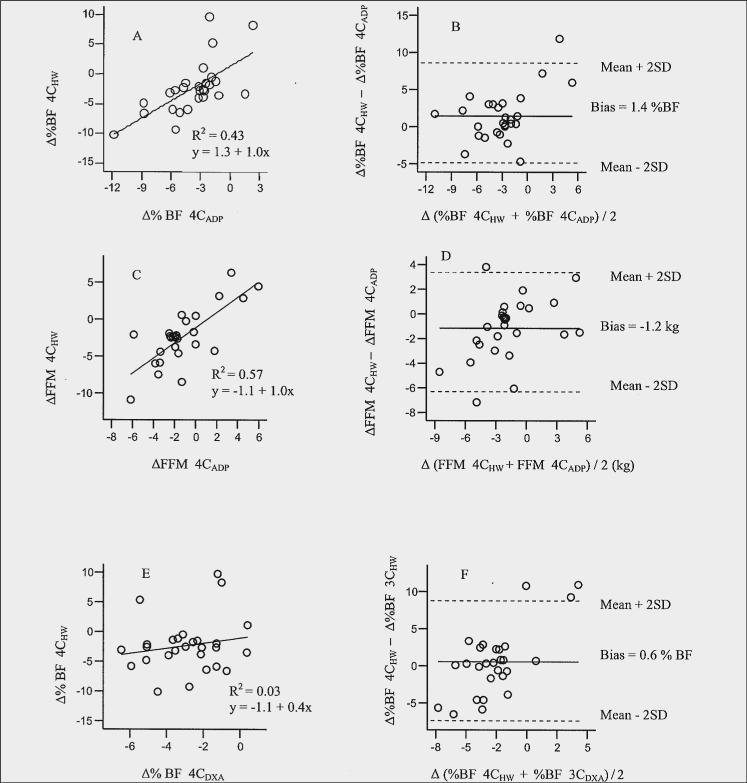

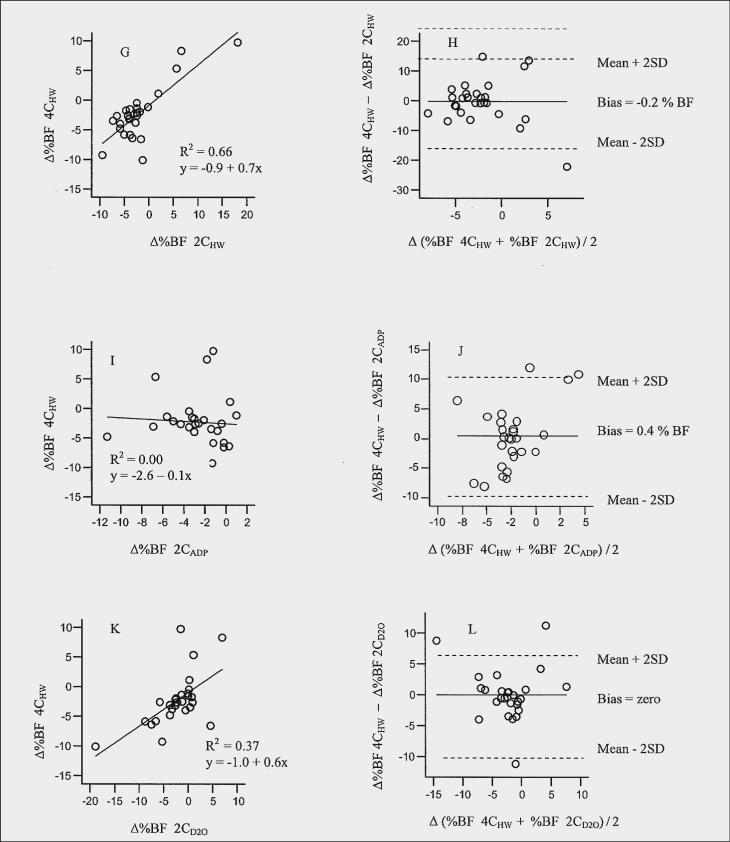

Δ% body fat

The results of the delta difference (single difference 4CHW minus single difference comparison method) for each pair of method's estimate of Δ%BF are presented in Table 3). The limits of agreement showed considerable variation and lack of agreement between 4CHW and each of the methods (14.5 to −14.1 %BF). A significant bias detected between 4CHW and 4CADP (Figure 1B) indicated 4CADP overestimated Δ%BF compared to 4CHW (4CADP > 4CHW, bias = 1.3 %; limits of agreement, 8.1 to −5.4%). The limits of agreement suggest that the two methods would give measurements that differ by ∼8% to −5%. It appears that 4CHW detects less change in Δ%BF compared to 4CADP. An adjustment to 4CADP (the new method being compared to 4CHW) can be made by subtracting the bias from the estimates of Δ%BF from 4CADP (30). Bland-Altman plots of Δ%BF for 2CHW, and 2CD2O compared to 4CHW (Figures 1H and 1L, respectively) showed that there was no recognizable relationship between the mean and the delta differences. In other words, the magnitude of the delta difference did not appear to be affected by the amount of Δ%BF, whereas this trend was observed between 4CHW and 3CDXA (Figure 1F) and between 4CHW and 2CADP, (Figure 1J).

Table 3.

Comparison of methods and models to estimate body composition changes (delta difference) due to energy restriction in postmenopausal women to the four compartment hydrostatic weighing criterion method

| Method/Models | Delta Difference single difference criterion method - single difference comparison method (ΔΔ) | Limits of Agreement1 (95%) |

|---|---|---|

| % BODY FAT | ||

| 4CHW - 4CADP | 1.4 ± 3.42 | 8.1 to −5.2 |

| 4CHW - 3CDXA | 0.6 ± 4.5 | 9.4 to −8.3 |

| 4CHW - 2CHW | −0.2 ± 7.3 | 14.5 to −14.1 |

| 4CHW - 2CADP | 0.4 ± 5.4 | 10.9 to −10.1 |

| 4CHW - 2CD2O | 0.0 ± 4.1 | 8.0 to −8.1 |

| FAT MASS (kg) | ||

| 4CHW - 4CADP | 0.6 ± 2.72 | 5.9 to −4.6 |

| 4CHW - 3CDXA | 0.1 ± 3.1 | 6.2 to −6.0 |

| 4CHW - 2CHW | −0.9 ± 3.7 | 6.3 to −8.1 |

| 4CHW - 2CADP | 0.2 ± 3.8 | 7.8 to −7.3 |

| 4CHW - 2CD2O | −0.2 ± 2.9 | 5.6 to −5.9 |

| FAT-FREE MASS (kg) | ||

| 4CHW - 4CADP | −1.2 ± 2.52 | 3.7 to −6.0 |

| 4CHW - 3CDXA | −0.4 ± 3.3 | 6.2 to −6.9 |

| 4CHW - 2CHW | −0.5 ± 4.1 | 7.5 to −8.4 |

| 4CHW - 2CADP | −0.4 ± 3.8 | 7.1 to −7.9 |

| 4CHW - 2CD2O | 0.0 ± 3.0 | 6.0 to −6.0 |

Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise noted; 4CHW = 4-compartment model using hydrostatic weighing for body volume, 4CADP = 4-compartment model using air-displacement plethysmography for body volume, 3CDXA, 3-compartment model dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, 2CHW= 2-compartment model hydrostatic weighing, 2CADP= 2-compartment model air-displacement plethysmography, 2CD20 = 2-compartment model deuterium oxide dilution technique for measurement of total body water.

Limits of agreement represent the agreement between 4CHW and the comparison method based on Bland-Altman (ΔΔ ± 2SD)

Comparison significantly different based on paired t-test, P < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Relation between a) change in % body fat (Δ%BF) estimated by 4CHW compared with 4CADP; b) delta difference (ΔΔ) against mean change (Δ) in %BF by 4CHW compared with 4CADP;, c) Δ fat-free mass (FFM) estimated by 4CHW compared with 4CADP; d) ΔΔFFM against ΔFFM by 4CHW compared with 4CADP; e) Δ%BF estimated by 4CHW compared with 3CDXA; f) ΔΔ%BF against Δ%BF by 4CHW compared with 3CDXA; g) Δ%BF estimated by 4CHW compared with 2CHW; h) ΔΔ%BF against Δ%BF by 4CHW compared with 2CHW; i) Δ%BF estimated by 4CHW compared with 2CADP; j) ΔΔ%BF against Δ%BF by 4CHW compared with 2CADP; k) Δ%BF estimated by 4CHW compared with 2CD2O; l) ΔΔ%BF against Δ%BF by 4CHW compared with 2CD2O

Δfat mass

The results of the delta difference for each pair of method's estimate of ΔFM compared to the 4CHW estimate are presented in Table 3. Compared to 4CHW model there was considerable variation in agreement between all methods for ΔFM (7.8 to −8.1 kg FM). A significant systematic bias was detected between 4CHW and 4CADP (bias = 0.6, limits of agreement, 5.9 to −4.6 kg FM), however not between 4CHW and other methods (Bland-Altman plots not shown).

Δfat-free mass

The results of the delta difference for each pair of method's estimate of ΔFFM compared to the estimate by 4CHW are presented in Table 3. Compared to 4CHW there was considerable variation for agreement between all methods for ΔFFM (7.5 to −8.4 kg FFM). A significant bias detected between 4CHW and 4CADP indicated 4CADP underestimated ΔFFM compared to 4CHW (4CADP < 4CHW, −1.2 kg; limits of agreement, 3.7 to −6.0 kg), Figure 1D. The level of ΔFFM affected agreement between the methods. The Bland-Altman plot shows that the larger the ΔFFM the less likely the methods will agree.

Regression coefficients after energy-restriction induced weight loss

In general, the amount of variance between 4CHW and other methods ranged from 0% to 66% for %BF, 0 % to 49 % for FM and 0% to 45% for FFM. %BF estimated with 2CHW accounted for 66% of the variance in %BF measured by 4CHW as indicated by the R2 value (R2 = 0.66, figures 1G). Other relatively high correlations included FM 4CADP (R2= 0.51) figure not shown, and FFM 4CADP (R2= 0.57), figure 1C, followed by %BF 4CADP (R2= 0.43), figure 1A and FFM D2O (R2 = 0.49), figure not shown. However, correlation coefficients were lowest for %BF 3CDXA and 2CADP, R2 = 0.00 and 0.03, figures 1E and 1I, respectively) FM 2CADP and 3CDXA, R2 = 0.07 and 0.18, respectively, and FFM 2CADP and 3CDXA, R2 = 0.0.02 and 0.33, respectively. Table 4 shows additional regression coefficients for %BF, FM, and FFM for each method in relation to 4CHW. Slopes for prediction of %BF by 4CHW from the comparison methods resulted in slopes from −0.1 to 1.0; prediction of FM 0.3 to 0.8 and prediction of FFM 0.5 to 2.1.

Table 4.

Regression results for body composition changes (single difference) due to energy restriction in postmenopausal women

| Variable | R2 | Slope | Y-intercept | SEE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | Independent | ||||

| Δ% BODY FAT | |||||

| 4CHW | 4CADP1 | 0.43 | 1.0 ± 0.22, 3 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 3.4 |

| 4CHW | 3CDXA | 0.03 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | −1.1 ± 1.6 | 4.5 |

| 4CHW | 2CHW1 | 0.66 | 0.7 ± 0.12 | −0.9 ± 0.6 | 2.7 |

| 4CHW | 2CADP | 0.00 | −0.1 ± 0.3 | −2.6 ± 1.32 | 4.5 |

| 4CHW | 2CD2O1 | 0.37 | 0.6 ± 0.22 | −1.0 ± 0.82 | 3.6 |

| ΔFAT MASS (kg) | |||||

| 4CHW | 4CADP1 | 0.51 | 0.8 ± 0.22, 3 | 0.0 ± 1.0 | 2.4 |

| 4CHW | 3CDXA1 | 0.18 | 0.6 ± 0.32, 3 | −1.9 ± 1.4 | 3.0 |

| 4CHW | 2CHW1 | 0.42 | 0.4 ± 0.12 | −3.1 ± 0.62 | 2.5 |

| 4CHW | 2CADP | 0.07 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | −3.4 ± 1.22 | 3.2 |

| 4CHW | 2CD2O1 | 0.49 | 0.6 ± 0.12 | −2.2 ± 0.72 | 2.4 |

| ΔFAT-FREE MASS (kg) | |||||

| 4CHW | 4CADP1 | 0.57 | 1.0 ± 0.22, 3 | −1.2 ± 0.62 | 2.6 |

| 4CHW | 3CDXA1 | 0.33 | 2.1 ± 0.62, 3 | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 3.2 |

| 4CHW | 2CHW1 | 0.42 | 0.5 ± 0.12 | −1.5 ± 0.62 | 3.0 |

| 4CHW | 2CADP | 0.02 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | −1.3 ± 1.7 | 3.9 |

| 4CHW | 2CD2O1 | 0.45 | 0.7 ± 0.22, 3 | −0.7 ± 0.7 | 2.9 |

Values are mean ± SE;

regression model is acceptable, prediction of variable with 4CHW from variable by comparison method,

significantly different than 0,

confidence interval includes 1, 4CHW = 4-compartment model using hydrostatic weighing for body volume, 4CADP = 4-compartment model using air-displacement plethysmography for body volume, 3CDXA, 3-compartment model dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, 2CHW= 2-compartment model hydrostatic weighing, 2CADP= 2-compartment model air-displacement plethysmography, 2CD20 = 2-compartment model deuterium oxide dilution technique for measurement of total body water

Discussion

The data from this study indicate that on a group basis the methods compared against the 4CHW model (4CADP, 3CDXA, 2CHW, 2CADP, and 2CD2O) are interchangeable to quantify group changes in %BF, FM and FFM with diet-induced weight loss in overweight and obese postmenopausal women. However, for an individual, there were large differences as indicated by the wide limits of agreement for each variable suggesting that individual estimates of changes in body composition when taken alone should be interpreted with caution. Currently there are no standard acceptable limits of agreement within body composition literature. Acceptance of limits of agreement requires use of clinical judgement because it is not a hypothesis test (31). For this reason, we support use of regression equations to obtain more acceptable individual estimates of changes in body composition that will relate to the criterion method, which in this case was the 4CHW method. Additional consideration should be given to small magnitude changes that occur as a result of normal variation in day-to-day activities, fluid balance and diet. Therefore, to detect true changes in body composition due to energy restriction it is necessary to achieve changes in %BF, FM and FFM beyond the variation of the body composition method. The method variability of the body composition techniques, ∼1% to 4.6% in the present study, must be considered when choosing a method to estimate changes in body composition.

Comparison of the methods in the current study was based on changes in body composition due to energy restriction. Most of the previous studies have examined changes in body composition that occurred due to gastric surgery (32) or exercise (33-35), plus diet-induced energy restriction (5, 36). None used the same methods for comparison. In addition to these studies examining changes in body composition, there have been numerous cross-sectional studies comparing various combinations of 2C-, 3C- and 4C models, but since weight loss was not a factor, comparison with these studies is not appropriate.

Frisard et al. (37) compared 3CDXA (criterion method), 2CADP and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) to assess changes in body composition after weight loss in 56 obese men and women. Similar weight loss occurred in this study (−5.6 ± 5.5 kg vs. −6.8 ± 3.2 kg in the current study). They found significant bias whereby Δ%BF and ΔFFM were overestimated by 2CADP and BIA at a lower %BF and underestimated at a higher Δ%BF and ΔFFM when compared to 3CDXA. High variability was also observed with FFM and FM. Frisard et al. (37) showed that 3CDXA might be more accurate with larger changes in weight loss in contrast to Jebb et al. (38), whereby 3CDXA overestimated %BF at higher tissue thickness. Comparing results among studies using 3CDXA (criterion method) is complicated because 3CDXA results have been shown to vary among instrument manufacturers, test modes (pencil beam compared with fan beam), software versions and tissue thickness (39). In addition, degree of obesity has been associated with measurement error and analysis mode should be consistent among laboratories (40). Recently, Schoeller et al. (29) demonstrated that 3CDXA estimates for lean and fat mass can significantly vary among differing 3CDXA models (hardware and software) under different laboratory conditions and recommended a 5% correction factor be applied when using QDR 4500A fan-beam 3CDXA instrument. This was obtained from cross-sectional data that included men and women ages 19−82 y, n = 1195. We did not use this model in the current study and therefore would not apply this correction factor. The DXA instrument used in this study, LUNAR Prodigy™ fan-beam has been found to be similar to DXA using pencil-beam geometry (41). However, this was not demonstrated when QDR2000 pencil-beam vs. QDR 4500A fan-beam were compared (42).

Evans et al. (36) compared 3CDXA, skinfolds, bioelectrical impedance and BMI using 4CHW as the criterion model in premenopausal obese women who lost weight due to diet or diet plus exercise. Similar results for Δ%BF (ΔFM and ΔFFM were not reported) in both groups were found among the methods, but the authors indicated there was the limitation of accurately detecting small Δ%BF among these methods. They observed a bias between 3CDXA and 4CHW whereby 3CDXA overestimated the loss in Δ%BF (1.3 ± 2.1% BF). We did not observe a bias between these two methods, but did observe a trend for 3CDXA to be influenced by the magnitude of Δ%BF (Figure 1F).

In the present study, a comparison of agreement between the methods for individual differences between Δ%BF estimates from 4CHW and 4ADP, 3CDXA, 2CHW, 2CADP and 2CD2O ranged from −14.5% to 14.1% (see Figures and Table 3). Large differences (10% to 15%) have been observed in other cross-sectional method comparison studies between 2CADP and 3CDXA (criterion method) that used both larger and smaller populations (43-45). The limits of agreement in this study were narrowest between 4CHW and 4CADP, 2CD2O, 3CDXA, 2CADP and 2CHW following in increasing ranges of limits of agreement for Δ%BF. The estimates between 4CHW and 4CADP and between 4CHW and 3CDXA each identified a trend that was not identified with the other methods (2CHW, 2CD2O, and 2CADP) (Figures 1H, 1J, lL). Bland-Altman plots identified a bias between 4CHW and 4CADP for Δ%BF (1.3%, Figure 1b) and ΔFFM (−1.2 kg, Figure 1D). For Δ%BF, 4CADP estimated a higher Δ%BF and a lower estimate of ΔFFM than 4CHW. No other biases were observed for the other comparisons to 4CHW. Bias between 4CADP and 4CHW would be likely due to differences in Db measurements detected at baseline between the two methods. It should be noted that change in Db was not significantly different based on method means (Table 1). However, the Bland-Altman plot between 2CHW and 2CADP for Db (figure not shown) yielded limits of agreement of −0.02 to +0.02 g/L for an individual. This may help explain why Bland-Altman plots of 4CHW and 4CADP reveal a bias since this is the only component that differed between 4CADP and 4CHW. The bias we observed between 4CADP and 4CHW was in a small population within one laboratory. We chose to follow the same testing order for all subjects (3CDXA, 2CADP, 2CHW, respectively) which were all completed within 1−2 hours of each other. It's possible that a bias could have been introduced and that randomizing the methods would have overcome bias. A larger population with similar subject characteristics and comparisons based on data reflecting changes in body composition needs to be similarly studied before a specific correction factor is recommended. Previous method comparison studies between 2CHW and 2CADP show that bias has been inconsistent in the direction of the differences between methods (24). It's possible that the limited number of subjects in this study influenced the bias since studies with largest mean differences have generally occurred in studies with the fewest subjects (24).

The individual differences between ΔFM and ΔFFM estimates from 4CHW and 4CADP, 3CDXA, 2CHW, 2CADP, and 2CD20 ranged between 7.8 to −8.1 kg and 7.5 to −8.4 kg, respectively. The differences were smaller between 4CHW and 4CADP, with 2CD20, 3CDXA, 2CADP and 2CHW following in increasing ranges of estimates for both ΔFM and ΔFFM. Overall, the individual estimates were greater for 2CHW, 2CADP, 3CDXA and 2CD20 than 4CHW and 4CADP for ΔFM and ΔFFM (Table 3). Although 4CHW and 4CADP differed between each other to a smaller degree, these differences were still large enough to not be interchangeable.

The estimation of changes in body composition is a challenge due to a number of factors including: changes in Db due to FM loss, muscle loss, TBW and BMC. The loss of FFM due to reductions in TBW can alter Db (46) as was observed in the present study, Table 1. Research by Fogelholm et al. (5) showed change in TBW/FFM and change in Db when comparing body composition estimates by 3CDXA, skinfolds, bioelectrical impedance, BMI, 4CHW, and HW during energy restriction in premenopausal obese women. They observed that 3CDXA and methods based on the 2C model underestimated loss of FM and attributed this to the increase in TBW/FFM that was observed (5). In contrast, we observed a decrease in TBW, but no change in TBW/FFM, Table 1. Fogelholm et al. (5) attributed the change in Db to a change in the water content of FFM (TBW), but our data do not support this since our subjects maintained the ratio of water content to FFM. A lack of change in TBW/FFM suggests there was a proportional change in FFM. Further, since the 2C and 3C models assume a constant fraction (TBW/FFM, ∼72−73%) (6, 47), it may partly explain why there were no group differences among the methods. In the current study postmenopausal women were adequately hydrated both prior to and during the energy restriction according to the normal standards noted above.

There was an increase observed for BMC/FFM, with no change in BMC (Table 1) observed. BMC changes with aging and varies due to body mass (25). Our results and others (5) do not show a change in BMC with short-term weight loss. Therefore, taken together these findings for changes in TBW/FFM and BMC/FFM suggest that the change with Db may be attributed to those that occurred with FFM and FM independent of BMC. This emphasizes the importance of using a 4C model when assessing significant changes in body composition due to weight reduction.

At present, 4CHW is not a realistic method for obtaining estimates of changes in body composition beyond research. More often in a clinical setting only one method is used to detect changes in body composition. Results of our regression analyses (Table 4) demonstrate the relationship between other methods and 4CHW. This enables users of the other body composition methods to predict a 4CHW estimate of body composition using one of the comparison methods. Thus, all of the methods in the current study, with the exception of 3CDXA for %BF and 2CADP for %BF, FM and FFM, may be used to obtain an estimate for changes in body composition for a postmenopausal woman.

In summary, the results of the present study indicate that 4CADP , 3CDXA , 2CHW, 2CADP , and 2CD2O provide comparable estimates of body composition changes with 4CHW on a group basis. However, the wide limits of agreement between 4CHW (the criterion method) and the comparison methods indicate that these methods are not interchangeable on an individual basis. Thus, regression equations should be employed in order to achieve estimates of changes in body composition that are related to a 4C model. These regression equations are limited to overweight and obese Caucasian women in general good health and to energy-restriction induced weight loss whereby physical activity was maintained. The lack of standard regression equations for varying populations and subject characteristics makes it currently problematic to interpret the reliability of individual estimates of body composition for any given method. Furthermore, interpretation of results for individuals with a given method requires knowledge of the limitations of the method. Thus, larger studies are much needed to further validate our regression equations and to examine the reliability of these methods for assessing weight changes in older populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the subjects who so generously gave their time and effort towards this project. In addition, the authors thank Dr. Stephen Badylak, MD, DVM, Ph.D., study physician, Zonda Birge, BS, for her analysis of urinary nitrogen, and Kim White, MS and April Stull, RD for their assistance with body composition measurements. Support: Cattlemen's Beef Board and the National Cattlemen's Beef Association (Centennial, CO), Agricultural Research Program & Lynn Fellowship at Purdue, and NIH R29 AG13409

Abbreviations

- Δ%BF

change in percent body fat

- ΔFM

change in fat mass

- ΔFFM

change in fat-free mass

- HW

hydrostatic weighing

- 2C

2 compartment

- ADP

air-displacement plethysmography

- DXA

dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- 3C

3-compartment

- TBW

total body water

- BMC

bone mineral content

- 4C

4-compartment

- BV

body volume

- D2O

deuterium oxide dilution

- CHO

carbohydrate

- PRO

protein

- Db

body density

- BW

body weight

- TBBM

total body bone mineral

- BMI

body mass index

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This PDF receipt will only be used as the basis for generating PubMed Central (PMC) documents. PMC documents will be made available for review after conversion (approx. 2−3 weeks time). Any corrections that need to be made will be done at that time. No materials will be released to PMC without the approval of an author. Only the PMC documents will appear on PubMed Central -- this PDF Receipt will not appear on PubMed Central.

References

- 1.Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM. Measurement of total-body fat by underwater weighing: new insights and uses for old method. Nutrition. 1993;9:472–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCrory MA, Gomez TD, Bernauer EM, Mole PA. Evaluation of a new air displacement plethysmograph for measuring human body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1686–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roubenoff R, Kehayias JJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Heymsfield SB. Use of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in body-composition studies: not yet a ”gold standard”. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:589–91. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brozek J, Grande F, Anderson JT, Keys A. Densitometric Analysis of Body Composition: Revision of Some Quantitative Assumptions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;110:113–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb17079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fogelholm GM, Sievanen HT, Lichtenbelt WDVM, Westerterp KR. Assessment of Fat-mass loss during weight reduction in obese women. Metabolism. 1997;46:968–975. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siri W. Body composition form fluid spaces and density: analysis of methods. In: Brozek J, Henschel A, editors. Techniques for Measuring Body Composition. National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council; Washington: 1961. pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaswani AN, Vartsky D, Ellis KJ, Yasumura S, Cohn SH. Effects of caloric restriction on body composition and total body nitrogen as measured by neutron activation. Metabolism. 1983;32:185–8. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(83)90227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarys JP, Martin AD, Drinkwater DT. Gross tissue weights in the human body by cadaver dissection. Hum Biol. 1984;56:459–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB, Lichtman S, Wang J, Pierson RN., Jr Body composition in elderly people: effect of criterion estimates on predictive equations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1345–53. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewitt MJ, Going SB, Williams DP, Lohman TG. Hydration of the fat-free body mass in children and adults: implications for body composition assessment. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:E88–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.265.1.E88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazariegos M, Wang ZM, Gallagher D, et al. Differences between young and old females in the five levels of body composition and their relevance to the two-compartment chemical model. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M201–8. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.m201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoeller DA, Jones PJ. Measurement of total body water by isotope dilution: a unified approach to calculations. In: Ellis SY KJ, Morgan WD, editors. In vivo Body Composition Studies. Institute of Physical Sciences in Medicine; London: 1987. pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albu J, Smolowitz J, Lichtman S, et al. Composition of weight loss in severely obese women: a new look at old methods. Metabolism. 1992;41:1068–74. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90287-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compston JE, Laskey MA, Croucher PI, Coxon A, Kreitzman S. Effect of diet-induced weight loss on total body bone mass. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992;82:429–32. doi: 10.1042/cs0820429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen LB, Quaade F, Sorensen OH. Bone loss accompanying voluntary weight loss in obese humans. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:459–63. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visser M, Gallagher D, Deurenberg P, Wang J, Pierson RN, Jr., Heymsfield SB. Density of fat-free body mass: relationship with race, age, and level of body fatness. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E781–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.5.E781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pritchard JE, Nowson CA, Wark JD. Bone loss accompanying diet-induced or exercise-induced weight loss: a randomised controlled study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendel HW, Gotfredsen A, Andersen T, Hojgaard L, Hilsted J. Body composition during weight loss in obese patients estimated by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and by total body potassium. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:1111–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsdale SJ, Bassey EJ. Changes in bone mineral density associated with dietary-induced loss of body mass in young women. Clin Sci (Lond) 1994;87:343–8. doi: 10.1042/cs0870343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishizawa Y, Koyama H, Shoji T, et al. Altered calcium homeostasis accompanying changes of regional bone mineral during a very-low-calorie diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:265S–267S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.1.265S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clasey JL, Kanaley JA, Wideman L, et al. Validity of methods of body composition assessment in young and older men and women. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1728–38. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.5.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heymsfield S, Lichtman S, Baumgartner R, et al. Body composition of humans: comparison of two improved four-compartment models that differ in expense, technical complexity, and radiation exposure. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:52–58. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clasey JL, Gater DR., Jr A comparison of hydrostatic weighing and air displacement plethysmography in adults with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:2106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fields DA, Goran MI, McCrory MA. Body-composition assessment via air-displacement plethysmography in adults and children: a review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:453–67. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazess RB, Barden HS, Hanson JA. Body composition by dual-photon absorptiometry and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Basic Life Sci. 1990;55:427–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1473-8_60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behnke AR, Feen BG, Welham WC. The specific gravity of healthy men. Journal of the American Medicial Association. 1942;118:495–498. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schloerb PR, Fris-Hansen BJ, Edelman IS, Solomon AK, Moore FD. The measurement of total body water in the human subject by deuterium oxide dilution. J Clin Invest. 1950;29:1296–1310. doi: 10.1172/JCI102366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukaski H, Johnson P. A simple, inexpensive method of determining total body water using a tracer dose of D2O and infrared absorption of biological fluids. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;41:363–370. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.2.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoeller DA, Tylavsky FA, Baer DJ, et al. QDR 4500A dual-energy X-ray absorptiometer underestimates fat mass in comparison with criterion methods in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1018–25. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;i:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altman D. Practical Statistics for medical research. 1 ed Chapman & Hall; London, New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das SK, Roberts SB, Kehayias JJ, et al. Body composition assessment in extreme obesity and after massive weight loss induced by gastric bypass surgery. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E1080–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00185.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houtkooper LB, Going SB, Sproul J, Blew RM, Lohman TG. Comparison of methods for assessing body-composition changes over 1 y in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:401–406. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson M, Fiatarone M, Layne J, et al. Analysis of body-composition techniques and models for detecting change in soft tissue with strength training. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:678–686. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Ploeg GE, Brooks AG, Withers RT, Dollman J, Leaney F, Chatterton BE. Body composition changes in female bodybuilders during preparation for competition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:268–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans EM, Saunders MJ, Spano MA, Arngrimsson SA, Lewis RD, Cureton KJ. Body-composition changes with diet and exercise in obese women: a comparison of estimates from clinical methods and a 4-component model. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:5–12. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frisard MI, Greenway FL, Delany JP. Comparison of methods to assess body composition changes during a period of weight loss. Obes Res. 2005;13:845–54. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jebb SA. Measurement of soft tissue composition by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. Br J Nutr. 1997;77:151–63. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lohman T. Human Body Composition. In: Heymsfield SB, Lohman SG TG, Wang Z, editors. Human Body Composition. 2nd Edition Human Kinetics; Springfield, IL: 2005. pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakata Y, Tanaka K, Mizuki T, Yoshida T. Body composition measurements by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry differ between two analysis modes. J Clin Densitom. 2004;7:443–7. doi: 10.1385/jcd:7:4:443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazess RB, Barden HS. Evaluation of differences between fan-beam and pencil-beam densitometers. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;67:291–6. doi: 10.1007/s002230001147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tylavsky FA, Lohman TG, Dockrell M, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of 2 dual-energy X-ray absorptiometers with that of total body water and computed tomography in assessing changes in body composition during weight change. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:356–363. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sardinha LB, Lohman TG, Teixeira PJ, Guedes DP, Going SB. Comparison of air displacement plethysmography with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and 3 field methods for estimating body composition in middle-aged men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:786–93. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levenhagen DK, Borel MJ, Welch DC, et al. A comparison of air displacement plethysmography with three other techniques to determine body fat in healthy adults. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1999;23:293–9. doi: 10.1177/0148607199023005293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fields DA, Wilson GD, Gladden LB, Hunter GR, Pascoe DD, Goran MI. Comparison of the BOD POD with the four-compartment model in adult females. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1605–10. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200109000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vivian H. Heyward, Stolarczyk LM. Applied Body Composition Assessment. 1st ed Champaign; IL: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z, Deurenberg P, Wang W, Pietrobelli A, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB. Hydration of fat-free body mass: new physiological modeling approach. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E995–E1003. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.6.E995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]