Abstract

It is known that many mothers rapidly share the results of their BRCA1/2 genetic testing with their children, especially adolescent children. What is less known is the extent to which these mothers may engage fathers in a discussion concerning genetic counseling and the anticipated disclosure of genetic test results to children, or seek shared decision making in this context. This short communication addresses this issue by first examining mothers' and fathers' discussions concerning a research study of family communication. In our view, this conversation likely served as a precursor to, and proxy indicator of, maternal receptivity to partner input regarding the genetic counseling/testing-results disclosure process. We further evaluated how the quality of the parenting relationship is associated with mothers' decisions to include or not include the child's father in this study. Finally, this report addresses potential ways in which the genetic counselor may be able to facilitate parental communication regarding the evolving process of disclosure of genetic information to children and adolescents.

Keywords: BRCA1/2 testing, cancer, family communication, men, children

Introduction

It has previously been observed and reported that the process of genetic testing is a family--as opposed to an individual--process (Bower et al., 2002; DeMarco et al., 2007; Sobel & Cowan, 2000). In light of this, it is understandable that the communication of genetic information to potentially at-risk family members may present as an overwhelming and daunting task for some (Forrest et al., 2003; Hallowell et al., 2005a; Peterson et al., 2003). However, with regard to parent and child communication of genetic test results, upwards of 50% of mothers participating in genetic testing for hereditary breast/ovarian cancer risk via BRCA1/2 mutation analysis rapidly decide to disclose their test results to their children, and rates of disclosure are highest to adolescents (Tercyak et al., 2002; Tercyak et al., 2001a).

While the psychological impact of disclosure on children is largely unknown, preliminary data suggest it may engender children's cancer worry (Tercyak et al., 2001b). For mothers, disclosure to children appears to be partly motivated by elevated maternal distress levels; yet, maternal distress does not dissipate following disclosure (Tercyak et al., 2001a). Also, this disclosure to children is often performed by mothers alone, without the presence of another support person (DeMarco et al., 2005; Segal et al., 2004). This may be because many women undergoing BRCA1/2 genetic testing believe they are the “gatekeepers” of this information and therefore assume sole responsibility for disclosing this information to their children and sharing it with relatives (Segal et al., 2004; Tercyak et al., 2001a). This observation raises important questions about the extent to which parents may seek to engage one another in genetic testing discussions impacting their children, and what role, if any, the parenting relationship plays in this context?

Hallowell and colleagues (2005a) previously reported on the degree to which men (fathers) disclosed BRCA1/2 genetic test results to adult children. That article described a full range of family communication strategies, from complete secrecy to complete disclosure. Tested fathers and their nontested partners (usually mothers) carefully evaluated the benefit of openly sharing hereditary cancer information against the risk of heightening cancer-specific distress in children. In an additional study which examined the potential involvement of family members in at-risk men's decision-making regarding undergoing predictive BRCA1/2 testing, Hallowell and colleagues (2005b) reported that men perceived their female untested partners (again, almost exclusively mothers) as having a legitimate role in this process.

It stands to reason that the extent to which mothers and fathers may engage in a discussion concerning genetic counseling and testing could, in part, be affected by the concept of ‘parenting alliance.’ As described by Weissman and Cohen (1985), parenting alliance examines the degree of commitment and cooperation between members of a couple with respect to child-rearing. The soundness of this relationship is assessed in four specific dimensions, including how much each parent respects the judgment of the other and the overall desire of mothers and fathers to communicate openly and clearly with each other (Weissman & Cohen, 1985; Abidin & Brunner, 1995). More specifically, parents with a strong parenting alliance are more likely to communicate with each other about issues that may affect their offspring (Abidin & Brunner, 1995). It is therefore possible that the parenting alliance concept applies to parental discussions concerning genetic counseling and the potential disclosure of parental genetic test results to children.

As part of an ongoing investigation of these and other related issues (Tercyak et al., 2007), we sought to invite parenting dyads into a study of family communication regarding hereditary breast/ovarian cancer risk; specifically, we followed mothers who were tested for BRCA1/2 gene mutations. It was considered that discussion of this family communication research study would be a logical precursor to, and perhaps a leading indicator of, maternal receptivity to partner input regarding the genetic counseling and testing process. We viewed this opportunity for a child-focused genetic counseling and testing discussion between a mother and her co-parent (principally the child's father) as a naturalistic experiment in which to address the following hypotheses: first, that tested mothers would be willing to engage fathers in such a discussion and second, that parenting relationship quality would be differentially associated with whether or not that discussion took place.

Methods

Study Population

Study participants were mothers with one or more children within the age range of 8-21 years. All women were participating in pre-test genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1/2 mutations at one of three centers: Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington, DC, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA. These centers offer clinical research programs focusing on the identification and management of adult hereditary cancer syndromes, including hereditary breast/ovarian cancer.

Procedure and Measures

Women were considered potentially eligible for this prospective, longitudinal study if they participated in pre-test genetic counseling for BRCA1/2 and had provided a blood sample for mutation analysis, were mothers to at least one or more children in the age range of 8-21 years, were English-speaking, and able to provide valid informed consent (Tercyak et al., 2007). Eligible women were approached in-person for their possible inclusion in the study by their genetic counselor at the end of the pre-test genetic counseling session and after the provision of a blood sample for BRCA1/2 genetic testing. Potential participants were told that the study focused on parental attitudes and beliefs about sharing their BRCA1/2 test results with their children, as well as their actual disclosure decisions and psychological outcomes. It was further explained that study participants would complete a sequence of three scheduled telephone interviews (one prior to results disclosure, and two afterwards [see below]). For those mothers who reportedly shared the responsibility of raising the child with a partner, they were informed of the opportunity for fathers to participate in the study as well; however, father participation required that a mother disclose her own study participation status to him and discuss the study's focus on communicating BRCA1/2 genetic test results with children.

Eligible and consented mothers and fathers were then asked to complete a multidimensional baseline telephone survey prior to the mothers' receipt of her genetic test results and two follow-up telephone surveys at one and six months after the receipt of test results. All surveys consisted of validated items and scales derived primarily from the behavioral decision making and decision support, family communication, and psychosocial genetic testing research literatures (Tercyak et al., 2007); motivations for study participation, sociodemographics, and clinical information were ascertained via interview as well.

Germane to the current analysis, parenting relationship quality was assessed via maternal report at baseline by two separate indices: marital status and a standardized and highly reliable self-report scale, the Parenting Alliance Measure (PAM) (Konold et al., 2001). The PAM is a 20-item clinical measure of the strength of the child-rearing alliance between parents. It assesses the parenting aspects of a couple's relationship (e.g., how cooperative, communicative, and mutually respectful they are with regard to caring for their child/ren). Items on the PAM are rated on a 5 point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree; possible range = 20-100) and summed together to yield a total score; higher scores are associated with stronger and more positive parenting alliance, while lower scores are associated with greater parenting discord. The PAM is very reliable and stable over time (Cronbach's coefficient alpha = 0.97, test-retest reliability r = 0.80; Abidin et al., 1999), measures the same dimensions for mothers and fathers alike (Konold et al., 2001), and validity studies show the PAM to be negatively correlated with parenting stress, family and marital dysfunction, and children's social skills and psychosocial adjustment problems (Abidin & Brunner et al., 1995; Bearss et al., 1998).

Results

Of the 303 mothers approached and determined to be eligible for possible inclusion in the study, 239 (79%) consented to take part in the research and 64 (21%) declined. Reasons for maternal decline were primarily due to lack of time and interest. There were no demographic differences between mothers who did and did not consent to the study with respect to key sociodemographic indicators (Tercyak et al., 2007). Among the 239 consented mothers, 208 (87%) reportedly shared in the upbringing of their children with another parent (primarily the child's father). Of these 208 mothers with a father involved in raising the child, 177 (85%) had complete study data and were subsequently analyzed; missing data were primarily due to pending or incomplete response. Descriptive characteristics of the maternal sample are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of maternal study sample (N = 177)

| Age | M = 45.9 | SD = 6.0 |

| Race | Caucasian n = 148, 84% | Noncaucasian n = 29, 16% |

| Education | ≥ College n = 135, 76% | < College n = 42, 24% |

| Marital status | Married n = 154, 87% | Not married n= 23, 13% |

| Number of first-degree relatives with breast/ovarian cancer | 1+ Relatives n = 88, 50% | 0 Relatives n = 89, 50% |

| Personal history of breast/ovarian cancer | Yes n = 100, 57% | No n = 77, 43% |

| Proband status | Yes n = 137, 77% | No n = 40, 23% |

We found that a majority (76%, n = 135) of our 177 mothers were willing to inform fathers about the family communication study and 24% (n = 42) were not; this difference in the proportion of those who informed vs. did not inform fathers was highly statistically significant, X2 (1) = 48.86, p < .0001.

When mothers were asked about their reasons for not informing the child's father about the study, most stated their beliefs that fathers would be too busy or uninterested in joining to warrant such discussion; several mothers also expressed sentiments of parenting relationship discord between the parenting dyad preventing such discussion from taking place.

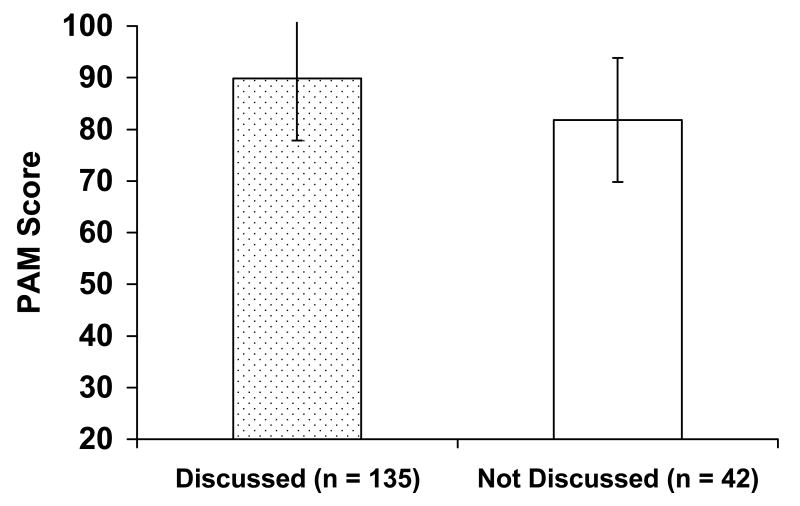

When examined in a bivariate fashion using marital status and the PAM as indices of parenting relationship quality, both indices were significantly associated with study communication. Mothers in in-tact married relationships with the child's father were overrepresented among those who discussed the study, X2 (1) = 11.82, p = .0006; mothers who discussed the study also reported significantly less parenting discord with the child's father, t (47.2) = 2.93, p = .005 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean differences in parenting alliance on the Parenting Alliance Measure (PAM) as a function of study communication between mother-father dyads

Note. Higher scores on the PAM are associated with stronger and more positive parenting alliance.

These associations were then examined simultaneously in a multivariate fashion using hierarchical regression analysis that adjusted for key sociodemographic and maternal medical history variables (i.e., marital status, number of first-degree relatives with breast/ovarian cancer, personal history of breast/ovarian cancer, proband status). It was observed that a significant portion (18%) of the model variance in parenting alliance was accounted for, F (5, 171) = 8.59, p < .001 (see Table 2): mothers who were married and those who had discussed the study reported the least parenting discord with the child's father, even after other potential confounder variables were controlled.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of mother-father dyadic parenting alliance

| Variable | B | SE B | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status (0 = not married, 1 = married) | 13.66 | 2.82 | 4.85 | <.0001 |

| Number of first-degree relatives with breast/ovarian cancer (0 = 0 relatives, 1 = 1+ relatives) | 0.73 | 1.80 | 0.41 | .68 |

| Personal history of breast/ovarian cancer (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 3.57 | 2.12 | 1.68 | .09 |

| Proband status (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 2.81 | 2.43 | 1.16 | .25 |

| Communication (0 = not discussed, 1 = discussed) | 5.29 | 2.22 | 2.39 | .02 |

Discussion

Our data suggest that a majority of mothers are willing to engage nontested fathers in a child-focused discussion about genetic testing. When mothers were unwilling, they appeared to protectively buffer their co-parent against his involvement, with greater communication barriers and relationship discord. Along with Hallowell and colleagues (2005a; 2005b), our data shed light on the complementary roles that parents play in discussing genetic issues surrounding children. In many cases, tested mothers and fathers contribute equally to this process. In other cases, tested mothers contribute more and either afford nontested fathers less opportunity to participate or fathers themselves opt not to engage more fully when invited to do so. Our results indicate that 76% of mothers openly discussed the genetic testing and family communication research project with fathers and 24% chose not to do so. Further investigation is necessary to better understand factors that may contribute to this phenomenon, especially among various cultural groups (Schneider et al., 2006).

Our data underscore the notion that some women who participate in genetic testing may seek to make private their decisions regarding such testing (Manne et al., 2004; Segal et al., 2004), in isolation from (and without the benefit of) another parent's input. As cautioned by Hallowell and colleagues (2005a), excluding partners from discussions about disclosing genetic testing has the potential to engender resentment and inhibit subsequent family communication about inherited cancer risks. Conversely, including partners likely promotes informed decision making and leads to better outcomes. It has previously been reported that maternal disclosure of BRCA1/2 test results to children is more likely to take place within the context of a more open parental communication style, and may depend upon the age of the children (Tercyak et al., 2002). It stands to reason that this type of communication decision making, coupled with a stronger parenting relationship, may also help to facilitate a discussion between mothers and fathers about maternal genetic testing and allow for greater involvement and support from spouses and partners. Furthermore, an open family communication style along with partner support were reported to be important factors involved in coping with the emotional distress that may accompany the genetic testing process (van Oostrom et al., 2007). Incorporating a discussion regarding family communication style into the genetic counseling session may provide an understanding regarding how social networking may impact the disclosure process between parents and their children (DeMarco et al., 2007). Examples of this might include counselors asking questions such as “How close are you and your partner?, “How much information do you typically share with your partner or children about your health?”, “How might you decide to share health information with your partner and children--what steps might you take?”, and “Describe for me some examples of how you have talked openly with your child in the past about a sensitive issue.” These initial probing questions could help set the stage for additional follow-up on this topic, particularly as test results become available. It would not be uncommon for some mothers to delay their decision about family communication of BRCA1/2 genetic test results until those results are known and mothers have had an opportunity to discuss them with a genetic counselor. As stated, mothers may make different decisions about family disclosure based upon the age, gender, or other characteristics of their children, along with their personal values and preferences about open family communication. In addition, their decision to disclose may also be driven (in part) by actual test results.

Finally, it is important to recognize that the communication of genetic test results amongst mothers and fathers and within families is an ongoing process, often influenced by family culture. A study assessing the information needs of mothers undergoing genetic testing for BRCA1/2 to help them in communicating their test results to their children indicated that they would like to have more written literature with respect to this issue and also to engage in additional family-centered counseling (Tercyak et al., 2007). In response to this need, we are developing and will be evaluating a comprehensive resource for mothers navigating the process of parental disclosure of genetic test results. This resource primarily consists of a decision aid aimed to assist mothers with the complex issue of disclosure and to facilitate her informed decision making about family communication. The resource includes specific tips and suggestions for mothers to use to engage their child's father in a discussion regarding parental communication, and may also help to overcome some of the barriers (i.e., those possibly related to marital issues and parenting alliance) noted herein. This resource will be evaluated within the context of a research study to help assure its fit, relevance, and utility for these purposes. Use of written materials with pinpointed strategies for mother-father communication may serve to reinforce issues that may have been initially discussed during the genetic counseling process, effectively extending counseling beyond the consultation room and providing further support throughout the decision making processes.

Though our work sheds light on some factors that contribute to communication between parents about genetics, a more thorough analysis and explanation of this phenomenon seems warranted. For example, it is unclear if or how a conversation about a family communication research study relates to actual discussions among parents regarding genetic testing and disclosure to children. Other possible sources of influence that deserve greater attention include maternal stress, coping, and disposition, as well as women's past experiences with sharing health information with family members. Issues such as family functioning, marital quality, and spousal support, along with cultural beliefs and norms may impact the communication process and be equally important to examine as well.

In sum, enhanced support for communication decision making in-person via a genetic counselor, through decision aids, and with partners may be warranted among some mothers seeking genetic testing for hereditary susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer to prevent later family resentment and poorer outcomes among parents and offspring. To the extent that parenting dyads lack a strong, cooperative partnership in caring for their children, additional avenues of support for mothers should likely be pursued.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health (HG002686) to Dr. Tercyak; additional support was provided through the Fisher Center for Familial Cancer Research at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. The authors would like to thank the individuals who volunteered to participate in this research, as well as the clinical and research staff members involved in the project.

Contributor Information

Tiffani A. DeMarco, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

Beth N. Peshkin, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

Heiddis B. Valdimarsdottir, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

Andrea F. Patenaude, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Katherine A. Schneider, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Kenneth P. Tercyak, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

References

- Abidin RR, Brunner JF. Development of a parenting alliance inventory. J Clin Child Psychol. 1995;24:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin RR, Kornold TR. Parenting Alliance Measure professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bearss KE, Eyberg S. A test of the Parenting Alliance Theory. Early Educ Develop. 1998;9:179–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bower MA, McCarthy Veach P, Bartels DM. A survey of genetic counselors' strategies for addressing ethical and professional challenges in practice. J Genet Couns. 2002;11:163–186. doi: 10.1023/a:1015275022199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco TA, McKinnon WC. Life after BRCA1/2 testing: Family communication and support issues. Breast Disease. 2007;27:127–136. doi: 10.3233/bd-2007-27108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco TA, Tercyak K, Peshkin B. Risk communication and the family: assessing parental attitudes about coummunicating BRCA1/2 test results to children. Presented at the 24th annual meeting of the National Society of Genetic Counselors; Los Angeles, CA. 2005. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Forest K, Simpson SA, Wilson BJ, et al. To tell or not to tell: barriers and facilitators in family communication about genetic risk. Clin Genet. 2003;64:317–326. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell N, Ardern-Jones A, Eeles R, Foster C, Lucassen A, Moynihan C, Watson M. Communication about genetic testing in families of male BRCA1/2 carriers and non-carriers: patterns, priorities and problems. Clin Genet. 2005a;67:492–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell N, Ardern-Jones A, Eeles R, Foster C, Lucassen A, Moynihan C, Watson M. Men's decision-making about predictive BRCA1/2 testing: the role of family. J Genet Counsel. 2005b;14:207–217. doi: 10.1007/s10897-005-0384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konold TR, Abidin RR. Parenting alliance: a multifactor perspective. Assessment. 2001;8:47–65. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Audrain J, Schwartz M, Main D, Finch C, Lerman C. Associations between relationship support and psychological reactions of participants and partners to BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing in a clinic-based sample. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:211–225. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2803_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SK, Watts BG, Koehly LM. How families communicate about HNPCC testing: findings from a qualitative study. Am J Med Genet. 2003;119c:78–86. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KA, Chittenden AB, Branda KJ, Keenan MA, Joffe S, Patenaude AF, et al. Ethical issues in cancer genetics: I 1) whose information is it? J Genet Counsel. 2006;15:491–503. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal J, Esplen MJ, Toner B, Baedorf S, Narod S, Butler K. An investigation of the disclosure process and support needs of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;125:267–272. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel SK, Cowan DB. Impact of genetic testing for Huntington disease on the family system. Am J Med Genet. 2000;90:49–59. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000103)90:1<49::aid-ajmg10>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, DeMarco TA, Patenaude AF, Schneider KA, Garber JE, Valdimarsdottir HB, Schwartz MD. Information needs of mothers regarding communicating BRCA1/2 cancer genetic test results to their children. Genet Test. 11:249–255. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, DeMarco TA, Brogan BM, Lerman C. Parent-child factors and their effect on communicating BRCA1/2 test results to children. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Hughes C, Main D, Snyder C, Lynch JF, Lynch HT, Lerman C. Parental communication of BRCA1/2 genetic test results to children. Patient Educ Couns. 2001a;42:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, Streisand R, Lerman C. Psychological issues among children of hereditary breast cancer gene (BRCA1/2) testing participants. Psychooncology. 2001b;10:336–346. doi: 10.1002/pon.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oostrom I, Meijers-Heijboer H, Duivenvooden H, et al. Family system characteristics and psychological adjustment to cancer susceptibility testing: a prospective study. Clin Genet. 2007;71:35–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman SH, Cohen RR. The parenting alliance and adolescence. Adolescent Psychiatry. 1985;12:24–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]