Summary

Pluripotency is a unique biological state that allows cells to differentiate into any tissue in the body. Here we describe a novel candidate pluripotency factor, Ronin, that acts independently of canonical transcription factors and possesses a THAP domain, which is associated with sequence-specific DNA binding and epigenetic silencing of gene expression. Ronin is expressed primarily during the earliest stages of murine embryonic development, and its deficiency in mice produces periimplantational lethality and defects in the inner cell mass. Ronin ablation by a conditional knockout strategy prevents the growth of ES cells. Most critically, forced expression of Ronin allows ES cells to proliferate without differentiation under conditions that normally do not promote self-renewal, and it partly compensates for the effects of Oct4 knockdown. We demonstrate that Ronin binds directly to the HCF-1 protein, a key regulator of transcriptional control. Our findings identify Ronin as an essential factor underlying embryogenesis and ES cell pluripotency. Its direct binding to HCF-1 supports an epigenetic mechanism of gene repression in pluripotent cells.

Introduction

Pluripotency, a biological state restricted to certain embryonic cells, enables development into any cell type in the body (Pedersen, 1986). Because this property can be exploited for genetic engineering and holds great promise for applications in regenerative medicine, an important goal is to understand the molecular pathways unique to pluripotent cells. Embryonic stem (ES) cells, derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of blastocysts, are the most commonly used cell type in studies of early embryonic development and the pluripotent state (Evans and Kaufman, 1981; Martin, 1981; Thomson et al., 1998), largely because of their ability to self-renew in tissue culture for extended periods without differentiation.

Despite recent progress in reprogramming somatic cells to an embryonic-like state (so-called induced pluripotent stem, or iPS, cells) by manipulation of several key transcription factors (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Maherali et al., 2007; Okita et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2007; Wernig et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2007), the precise molecular mechanisms that underlie pluripotency remain elusive. It is proposed that a tightly balanced core set of specific transcription factors, able to promote self-renewal by repressing transcription factors that initiate differentiation programs, are the major driving forces in ES cell maintenance (Bernstein et al., 2006; Boyer et al., 2005; Boyer et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2006). A second tier of control is likely achieved via enzyme-mediated modifications of chromatin (e.g., histone acetylation and methylation at specific residues and chromatin remodeling) that may “prime” critical differentiation genes for subsequent transcription (Boyer et al., 2006; Houlard et al., 2006; Klochendler-Yeivin et al., 2000). Whether the epigenetic status of ES cells directly reflects the actions of transcription factors known to be involved in pluripotency, or perhaps those yet to be linked to the pluripotent state, remains unclear.

Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog are considered part of the core set of pluripotency factors (Avilion et al., 2003; Chambers et al., 2003; Nichols et al., 1998). Although each of these proteins has been described as a “master regulator” of pluripotency, only Oct4 appears absolutely essential, while both Sox2 and Nanog appear dispensable, at least in certain molecular contexts (Masui et al., 2007; Chambers et al., 2007). Contributing to the complexity of ES cell regulation is the observation that ectopic expression of Nanog, but not Oct4 and Sox2, will sustain self-renewal under unfavorable conditions, but does not override the differentiation effects of forced downregulation of either Oct4 or Sox2 (Chambers et al., 2003; Matsui et al., 1992; Niwa et al., 2000). Moreover, the exact manner in which particular epigenetic modifiers, such as histone-modifying enzymes, influence the state of pluripotency and engage in cross-talk with other pluripotency factors is unclear.

We previously showed that certain components of the cell death system, Caspase-3 in particular, specifically cleave and deplete Nanog protein, compelling ES cells to exit their self-renewal phase and induce differentiation (Fujita et al., 2008). This discovery led us to hypothesize that Caspase-3 might recognize other pluripotency factors critical for ES cell function, and to devise a yeast two-hybrid screen for Caspase-3 targets in ES cells that would fill this role. Here we describe a novel nuclear protein targeted by Caspase-3 that is expressed during the earliest stages of embryonic development, is essential for the maintenance of pluripotent stem cells both in vitro and in vivo, allows ES cells to self-renew under conditions that normally suppress self-renewal, and partly compensates for Oct4 knock-down in ES cells. Designated Ronin (a masterless Japanese samurai) because of its lack of any apparent relationship to known “master” regulators of pluripotency, this factor contains a zinc-finger DNA-binding motif (THAP domain) common to many proteins associated with chromatin modification and silencing of gene expression (Roussigne et al., 2003; Mcfarlan et al., 2005). Ronin binds directly to the HCF-1 protein, a key regulator of transcriptional control that is associated with protein complexes involved in histone modification, suggesting that it acts through a previously unrecognized pathway of pluripotency control.

Results

Identification of Ronin by Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

Previous studies by our group showed that Nanog is targeted and cleaved by the proapoptotic enzyme Caspase-3 upon induction of ES cell differentiation (Fujita et al., 2008), leading us to hypothesize that other, still unknown factors critical for ES cell pluripotency may be Caspase-3 targets as well. We therefore performed yeast two-hybrid screening of a human ES cell cDNA expression library, using constitutively active Caspase-3 (mCasp3rev) as bait. mCasp3rev spontaneously folds into its active conformation and recognizes and binds to target proteins, but no longer cleaves them owing to a C163S substitution. An estimated 32 million clones were screened, with 556 clones testing positive for interaction with the Caspase-3 mutant. Further study of a representative set of 286 clones, using rescued plasmids, digestion with restriction enzymes, and a validation assay, yielded 116 candidate genes. Subsequent sequencing and analysis with an in vitro transcription/translation Caspase-3 cleavage assay identified a cDNA whose protein product contained elements of a DNA-binding factor with striking similarities to the DNA-binding domain of the Drosophila P element transposase. This protein, termed Ronin for reasons given in the Introduction, proved to be an authentic target of Caspase-3 in further analyses (Figure S1A).

Characterization of the orthologous 305 residue Ronin protein encoded by the mouse cDNA (predicted length, 1809 bases) revealed a THAP domain at the N-terminus (Figure 1A), which comprises a zinc-finger DNA-binding motif defined, in part, by a C2CH signature (Cys-Xaa2–4-Cys-Xaa33–50-Cys-X-aa2). There are also two polyalanine motifs, a polyglutamine tract (22 Qs), and a predicted coiled-coil structural domain at the C-terminus. A nuclear translocation signal (NLS) is located towards the C-terminus. A search for Ronin orthologs across multiple animal species showed exceptional conservation of the N- and C-termini, even among more distant species (e.g., humans vs. zebrafish, Figure S1B, C). The most closely related nonvertebrate protein with a similar THAP domain is a transposase in the sea urchin (43% identity, seq XP_790851.2), which is related to several Drosophila transposases, including the P element transposase and the THAP domain-containing protein THAP9 in humans and other primates.

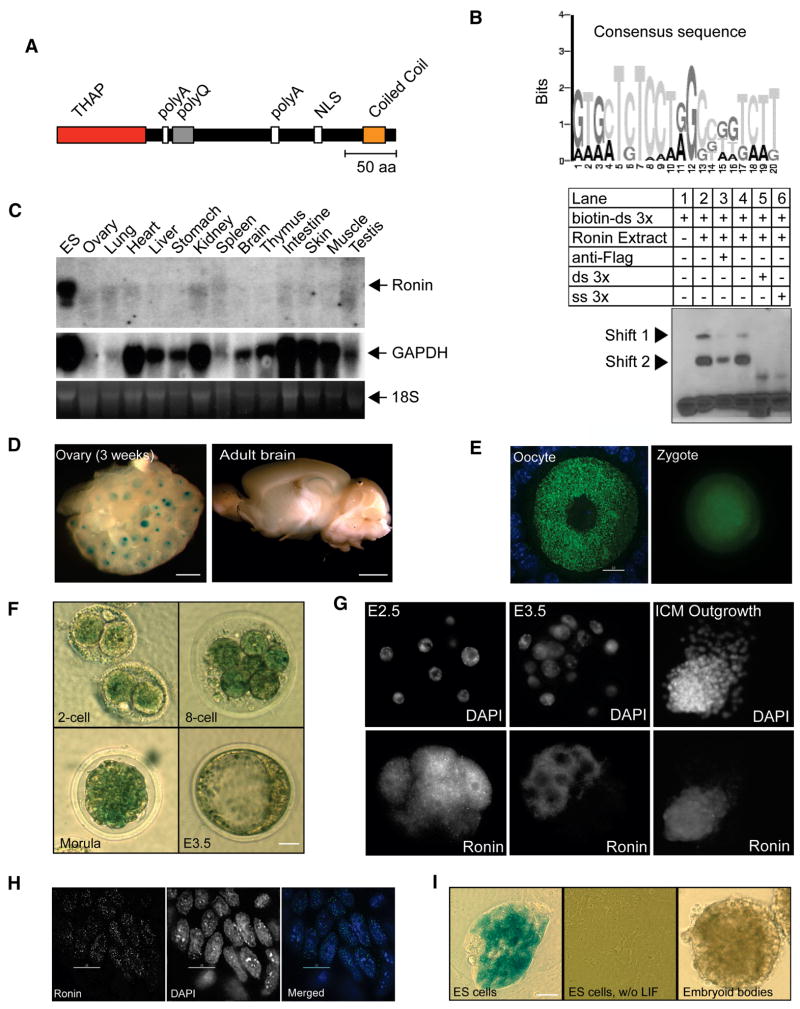

Figure 1. Ronin is a nuclear THAP domain protein whose expression is restricted to early embryonic cells and undifferentiated ES cells.

(A) Schematic diagram of the Ronin protein showing a THAP domain at the N-terminus. NLS, nuclear translocation signal; polyQ, polyglutamine tract; polyA, polyalanine sequence; THAP, Thanatos-associated protein; aa, amino acid. (B) SELEX identification of the consensus sequence recognized by Ronin DNA-binding motif (top) and gel-shift experiments with a specific DNA sequence (bottom). After the SELEX procedure, 104 sequences were analyzed, and a motif search identified a specific consensus (top) and a “3x sequence”. Binding of Ronin-Flag to the biotinylated 3x sequence was verified by gel-shift experiments that could be inhibited by the Flag antibody and either, double-stranded or single-stranded unlabeled competitor 3x molecules. Triangles indicate gel shift complexes. (C) Northern Blot analysis of multiple mouse tissues. Ronin expression was detected only in the positive control (mouse ES cell line R1); all other tissues lacked appreciable signals. (D) X-Gal staining of tissues isolated from mpRonin-lacZ reporter mice. Very strong positive staining was detected in the oocytes and in some areas of the adult brain. (E) Immunostaining of oocytes and zygotes isolated from adult females using a Ronin antiserum. Ronin was restricted to the ooplasm, but was prevalent throughout the zygote (bar = 10 μm) (F) Ronin promoter-driven lacZ expression was detected at the 2-cell stage of embryo development and intensified during the 8-cell and compact morula stages, but surprisingly subsided in the blastocyst stage. (G) Immunostaining of Ronin in morula and blastocyst stage embryos and in in vitro inner cell mass (ICM) outgrowth. Ronin protein is present throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus in morula-stage embryos but concentrated in the cytoplasm of the inner cell mass in the blastocyst. Ronin again is present in the nucleus of ICM outgrowth. (H) Confocal images of mouse ES cells stained with Ronin antibody. Ronin and DAPI are mutually exclusive. (I) lacZ expression was detected in undifferentiated ES cells grown in the presence of MEFs, while virtually no staining was apparent after differentiation in the absence of MEFs and LIF or after EB formation for 3 days. (scale bars: D left 30 μm, D right 80 μm, E left 30 μm, right 20 μm

To determine the DNA sequence recognized by Ronin, we used the SELEX procedure (Bouvet et al., 2000) with a mouse Ronin-His/V5 recombinant protein (see Experimental Procedures for details) to select random oligonucleotides for sequencing. We identified a consensus sequence (Figure 1B, top panel) as well as a specific sequence (3x) that was represented three times in the sequenced pool. Gel-mobility shift experiments confirmed that the 3x sequence is readily bound by Ronin (Figure 1B, bottom panel). Other related oligonucleotides were not able to abolish the gel shift, indicating that Ronin does not bind nonspecifically to either DNA or DNA ends (see Figure S1D). These data show that Ronin, like other proteins with a THAP domain, is a nuclear protein, as confirmed by immunofluorescence (see below), and binds to DNA in a sequence-specific manner. The coiled-coil motif at the C-terminus may represent a second functional domain, as indicated by its capacity to bind directly to the HCF-1 protein (see below).

Ronin Expression Patterns

Northern blot analysis of multiple tissues in the mouse failed to detect appreciable expression of the Ronin gene, except in the mouse ES cell line used as a positive control (Figure 1C). To further clarify the expression patterns of Ronin, we generated a lacZ transgenic reporter mouse line in which a 3.3-kb genomic fragment representing the mouse Ronin promoter was ligated into the open reading frame of the β-galactosidase gene. The resultant mouse line expressed β-galactosidase in tissues where the Ronin promoter was active, in a pattern similar to the expression of wild-type Ronin. As in the Northern blot analysis, Ronin was not abundantly expressed in adult tissues, with two exceptions: (i) ovary, which showed very strong positive staining in oocytes (Figure 1D, left), and (ii) some areas of the brain, including hippocampus, olfactory bulb and Purkinje cells (Figure 1D, right). To establish the subcellular compartment in which Ronin is found, we raised an antibody against Ronin (Figure S2A). Immunostaining with this antibody in adult ovaries showed localization of Ronin mainly in the ooplasm without any evidence of its presence in the nucleus (Figure 1E, left). This pattern of staining contrasted with the detection of Ronin throughout the zygote (Figure 1E, right).

Using the lacZ animal model to assess Ronin expression during early embryonic development, we found that lacZ activity first appears at the 2-cell stage, intensifies during the 8-cell and compact morula stages, but subsides in the blastocyst (Figure 1F). However, immunofluorescence staining revealed that Ronin protein was still present at the blastocyst stage (Figure 1G) indicating that the lacZ reporter system is not as sensitive as antibody staining and therefore could underestimate Ronin transcription by comparison with the results of RT-PCR or microarray analysis. Although present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of blastomeres in morula-stage embryos, Ronin appeared mainly in the cytoplasm of cells within the blastocysts, suggesting that its function may be regulated by shuttling of the protein between the cytoplasm and nucleus, similar to its fate at the oocyte/zygote transition. Once the blastocysts were placed in culture, the Ronin protein was again mostly localized in the nucleus with only scant amounts detected in the cytoplasm (Figure 1G).

Immunostaining for Ronin protein was strongly positive in the nucleus of undifferentiated mouse and human ES cells, and was distributed in an uneven pattern that primarily exluded DAPI-positive areas, suggesting that Ronin is an abundant nuclear protein associated with open chromatin (Figure 1H and Figure S2B). These results led us to study reporter gene activity in ES cells isolated from transgenic blastocysts to determine the temporal pattern of Ronin expression upon induction of differentiation. lacZ activity was detected in undifferentiated ES cells grown in the presence of a mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder layer (Figure 1I, left). When these cultures were transferred to gelatin-coated dishes and maintained in the absence of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and MEFs or incubated as hanging drops to form embryoid bodies (EB), lacZ activity was virtually undetectable in the differentiated cells (Figure 1I, middle and right). Overall, these findings indicate that Ronin expression is mainly restricted to pluripotent cells of the developing embryo, to oocytes and to certain regions of the adult brain.

Ronin Knockout Leads to Periimplantational Lethality

To test whether Ronin plays a critical role in early embryonic development, we knocked out a single allele of the gene in mouse ES cells, generating Ronin+/− mice (see Experimental Procedures). When Ronin+/− male and female littermates were crossed, none of the 98 offspring at weaning age were Ronin−/−, demontrating that a Ronin-null genotype is embryonically lethal. An estimated two-thirds of the offspring (67 animals) were Ronin+/− and one-third (31 animals) were Ronin+/+, supporting a lethal phenotype. To determine the embryonic stage of lethality, we crossed Ronin+/− animals and dissected and genotyped embryos at E7.5. Of the 26 decidua examined, 7 (27%) were empty, 8 (31%) contained embryos that were Ronin+/+, and 11 (42%) contained embryos that were Ronin+/−. Empty swollen decidua were similar in size to those containing embryos, an indication that implantation and decidualization had proceeded normally (Figure 2A, left). Crossing Ronin+/− females with Ronin+/+ males did not yield empty decidua. Approximately half of the resultant embryos were Ronin+/−, while the other half were Ronin+/+, as expected. We propose that the Ronin−/− embryos die either during or shortly after implantation, an outcome that was confirmed by the presence of residual embryonic tissue in empty decidua from uteri examined after crosses with Ronin+/− mice (Figure 2A, right).

Figure 2. Ronin is essential for normal embryogenesis and for ES cells survival.

(A) H&E staining of mouse uterine sections following Ronin+/− crosses. Empty swollen decidua (marked by an asterisk, bar = 1 cm, left) were similar in size to those containing wild-type embryos (middle), but displayed residual resorbed embryonic tissue (right) at day E6.5. (B) Phase contrast images of blastocysts and ICM outgrowth. Ronin−/− blastocysts isolated from Ronin+/− crosses were morphologically indistinguishable from their Ronin+/+ counterparts (left) but the ICM never proliferated (right) when cultured on gelatin coated culture plates, as would be expected for Ronin+/+ cells (bar = 30 μm) (C, left) Immunofluorescent images of Cre-GFP transfected ES cells. The Ronin+/f lox cells (green fluorescent) were viable while Roninf lox/− cells died rapidly (arrow indicates typical morphology of apoptotic cells). Genotyping of 88 colonies failed to identify any Ronin−/− cell (bar = 20 μm). (C, right) Immunofluorescent images of MEFs isolated from a Roninf lox/f lox animal. After transfection with GFP adenovirus, all MEFs showed green fluorescence indicating successful transfection (left panel, insert shows phase contrast image of transduced MEFs). PCR-based genotyping of Cre-GFP-transfected cells confirmed successful Cre-mediated excision of both Ronin alleles, resulting in viable Ronin−/− MEF cells (data not shown). (D–H) siRNA mediated knockdown of Ronin in ES cells. R1 cells were transfected with siRNA and the differentiation level assessed 4 days later (AP staining). (D) Phase contrast images showing no apparent difference in differentiation between control and Ronin siRNA while Oct4 siRNA is inducing differentiation. (E) Quantification of experiment shown in (D). (F) Quantification of colony number (independent of differentiation level); Colony number is reduced after treatment with Ronin siRNA compared to the control, but to a lesser extent than with Oct4 siRNA. (G) Proliferation rate of ES cells after treatment with siRNA. Cells treated with Ronin siRNA are showing significantly reduced proliferation rated when compared to control. (H) Quantification of Ronin expression by real time PCR of ES cells 18 hours after treatment with siRNA showing that Ronin expression level is reduced to 20%.

Next, superovulated immature Ronin+/− females were crossed with Ronin+/− males, and 45 blastocyst-stage embryos were isolated. Genotyping of these blastocysts, identified nine (20%) as Ronin−/−. Crossing Ronin+/− females with wild-type males produced the expected ratio of Ronin+/− and Ronin+/+ blastocysts. Upon gross examination, the Ronin−/− blastocysts were indistinguishable from Ronin+/+ and Ronin+/− blastocysts (Figure 2B, left). The vast majority (90%) of the inner cell masses (ICMs) of embryos resulting from additional Ronin+/− and Ronin+/+ crosses showed outgrowth when cultured on gelatin-coated culture plates, in contrast to those from Ronin−/− embryos, which either failed to proliferate or, in one instance, produced only a residual mass (Figure 2B, right). We propose that Ronin is essential for maintenance and proliferation of the ICM.

Ronin Knockout ES Cells Are Not Viable

The severe defects in ICM outgrowth in Ronin−/− embryos implicated Ronin activity as a critical factor in both the derivation and propagation of ES cells. Hence, we sought to derive ES cells from crosses of Ronin+/− mice. Although Ronin+/− ES cell lines could be readily generated, it was not possible to obtain Ronin−/− lines despite repeated attempts, indicating that Ronin activity is essential for generating ES cell lines in vitro. Even so, a knockout phenotype characterized by defects in the ICM would not necessarily militate against the growth and viability of cultured ES cells with conditionally deleted alleles. Thus, we generated Roninf lox/f lox ES cells, transfected them with a Cre expression vector and sorted for Cre recombinase-positive cells (see Experimental Procedures). Among 110 genotyped subclones, most (90%) were Roninf lox/−, with none lacking both alleles. Further testing of the Cre-transfected ES cells revealed a high rate of a phenotype resembling apoptotic death (Figure 2C, left), suggesting that Ronin knockout was lethal to ES cells under standard culture conditions. In contrast, when Roninf lox/f lox MEFs derived from E14.5-old embryos were isolated and treated with Cre adenovirus, nearly 100% of the cells were transduced, resulting in complete knockout of Ronin (Figure 2C, right). Finally, the Ronin loxP allele was crossed into the Mx1-Cre background to generate Roninf lox/f lox– Mx1-Cre ES cell lines (Whyatt et al., 1993), but the induction of Mx1-Cre did not lead to deletion of the Ronin allele in any experiment (data not shown). Interestingly, knockdown of Ronin using siRNA did not result in any overt phenotype in the colony formation assay (Figure 2D, E); however, colony formation and cell proliferation assays revealed a small but reproducible decrease in the colony number formed (Figure 2F) and a significant decrease the proliferation rate (Figure 2G), in agreement with our knockout data. The most likely interpretation is that the 50–80% knockdown efficiency we achieved (Figure 2H) is not sufficient to fully unmask the phenotype. Together, these findings demonstrate a stringent requirement for Ronin in maintenance of the self-renewal property of ES cells, as well as in the generation of the ICM during early embryogenesis.

Forced Expression of Ronin Inhibits Differentiation of ES cells

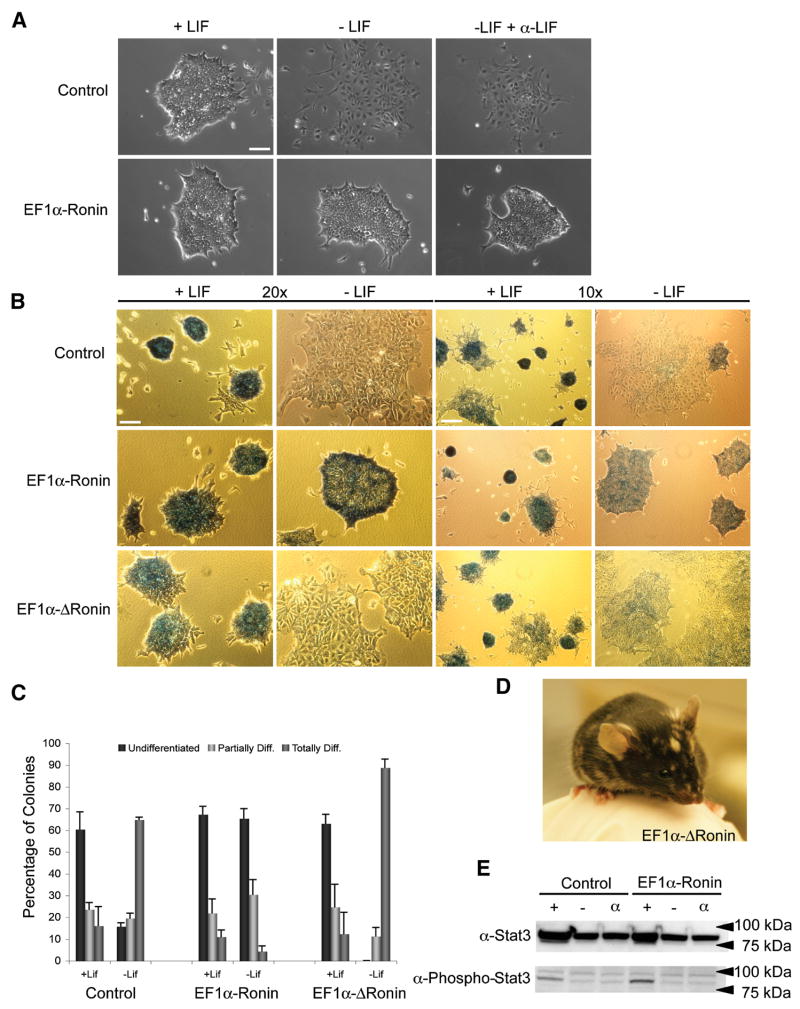

Because Ronin possesses several of the critical features of a pluripotency factor, we asked if its ectopic expression in ES cells would render them independent of LIF for self-renewal. In these experiments, we established stable ES cell lines expressing loxP-flanked Ronin under the influence of a constitutive promoter, EF1α. Western blot analyses were used to select several clones that expressed Ronin in ES cells and had normal morphology. To test the effects of Ronin overexpression on ES cell self-renewal, we plated control ES cells and those ectopically expressing Ronin (maintained without LIF or with a LIF-blocking antibody) at clonal densities and analyzed colony formation 4 days later. The vast majority of colonies overexpressing Ronin appeared morphologically unaffected by LIF removal or LIF inhibition, in contrast to ES cell controls, which were fully differentiated (Figure 3A). To quantify this result, we performed alkaline phosphatase staining 4 days after clonal plating and determined the percentages of undifferentiated, partially differentiated and fully differentiated ES cell colonies. As expected, in the absence of LIF, most of the control ES cell colonies were either partially (24%) or entirely (60%) differentiated, whereas two-thirds (65%) of the EF1α-Ronin ES cell colonies remained undifferentiated under the same conditions (Figure 3B, C). Furthermore, there was essentially no background differentiation in EF1α-Ronin ES cell cultures. This remarkable example of LIF-independent maintenance of pluripotency was further evaluated at the functional level by culturing ES cells without LIF for 8 days and subsequently removing the Ronin transgene with Cre recombinase. All control ES cells differentiated relatively quickly, to the extent that no cells with typical ES cell morphology remained in the culture when they were split after 4 days. In sharp contrast, the Ronin-expressing ES cells formed abundant colonies and could be split after 4 days of culture without LIF. After a total of 8 days in the absence of LIF, clones were expanded and the ectopic Ronin allele was removed by Cre transfection of expanded clones (EF1α – ΔRonin). These cells displayed properties indistinguishable from those of wild-type ES cells, including monolayer differentiation in medium without LIF (Figure 3B, C) and the ability to generate chimeric animals upon injection into blastocysts, similar to control cells (Figure 3D). These results indicate that the absolute differentiation block was not due to a secondary mutation in EF1α-Ronin ES cells. They also suggest that the pluripotency sustained by ectopic expression of Ronin is reversible.

Figure 3. Forced expression of Ronin inhibits differentiation of ES cells.

(A) Phase contrast images of control ES cells and EF1α-Ronin ES cells, stably overexpressing Ronin, after differentiation in monolayer cultures in the absence or presence of LIF for 4 days. Cells were split at clonal density under the same conditions. Cells that remained pluripotent after 8 days of selection were expanded in the presence of LIF on MEFs and, in a second step, Ronin expression was silenced by Cre-mediated recombination to obtain EF1α-ΔRonin ES cells (bar = 20 μm) (B) Alkaline phosphatase staining of cells treated as in panel A at two different magnifications. EF1α-Ronin cells remained phosphatase positive during differentiation, indicating their undifferentiated state. Control ES cells, as well as the reverted EF1α-ΔRonin ES cells showed reduced phosphatase staining, indicating normal differentiation (bar 10x = 80 μm, bar 20x = 40 μm). (C) Quantification of 3 × 50 colonies from the experiment described in panel B. The values are means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments. (D) Chimeric mice generated by injection of EF1α-ΔRonin ES cells into blastocysts. (E) Western blot analysis of Stat3 and Phospho-Stat3 indicating no difference between the amount and phosphorylation level of wild-type and Ronin-overexpressing ES cells after LIF removal.

We also asked whether Ronin can stimulate phosphorylation of Stat3 in the absence of LIF. Western blot analysis (Figure 3E) revealed that in ES cells ectopically expressing Ronin, Stat3 phosphorylation was not sustained after omission of LIF, indicating that the observed effects of Ronin are independent of LIF and Stat3 signaling.

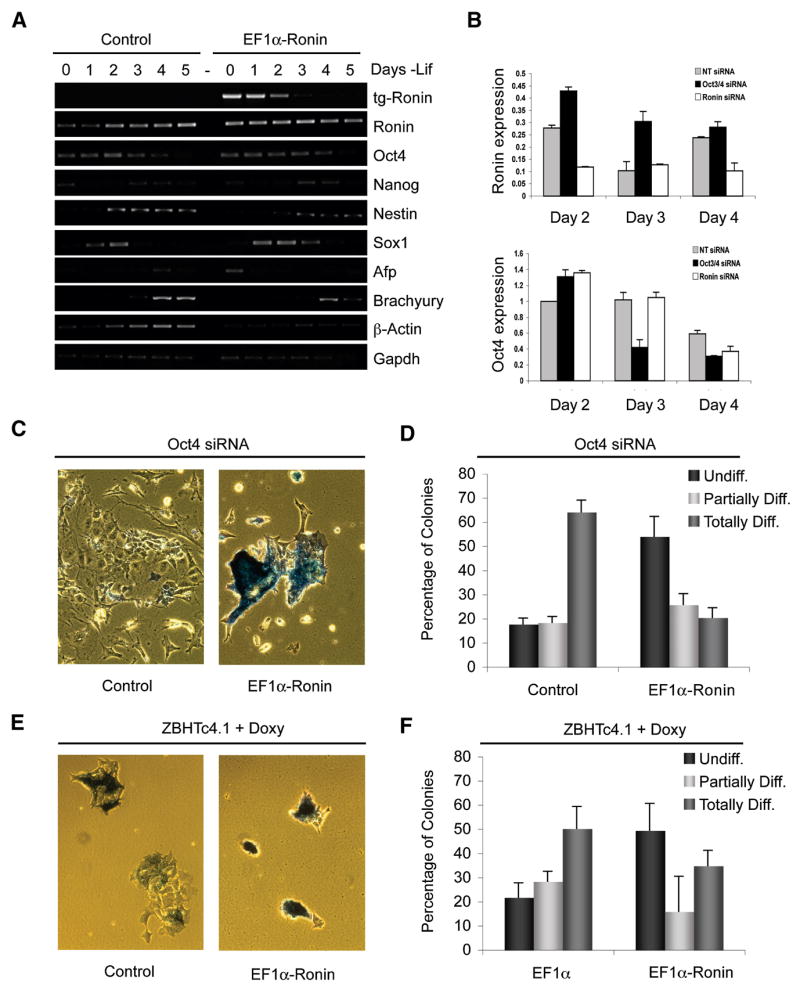

To assess the effects of constitutive expression of Ronin on (i) known pluripotency factors, (ii) marker genes for all three germ layers, and (iii) extraembryonic tissues, we isolated RNA from ES cells on days 1 through 5, after they were plated at low densities in medium without LIF. RT-PCR analysis revealed two provocative but conflicting results (Figure 4A): (i) virtually all differentiation markers were inhibited upon withdrawal of LIF, indicating that forced expression of Ronin inhibits differentiation, similar to findings with the teratocarcinoma formation assays (see below), whereas (ii) the amount of RNA for some housekeeping genes, such as β-actin, but not for others, such as Gapdh, was significantly reduced in repeated experiments (Figure 4A and S4). In agreement with our observation that these two genes respond differently to Ronin, we identified the Ronin DNA binding sequence in the β-actin gene but not in the Gapdh gene. Furthermore, we noticed that Ronin mRNA did not decrease as much as Oct4 (Figure 4A). This finding suggests that the repressive function of Ronin is not limited to specific developmental genes but extends widely over the transcriptome, a prediction we test in Figure 6.

Figure 4. Ronin inhibits differentiation independently of canonical pluripotency factors.

(A) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of pluripotency factors and marker genes for all three germ layers. Ectopic expression of Ronin delayed upregulation of differentiation markers. (B) siRNA against Oct4 and Ronin was transfected into ES cells and the expression of their mRNA determined at the indicated time points by real-time quantitative PCR. Data are reported as means and standard deviations of triplicate experiments. Knockdown of Oct4 resulted in its loss, but Ronin expression was not affected. (C) Alkaline phosphatase staining of ES cells after siRNA knockdown of Oct4. EF1α-Ronin ES cells showed a substantially higher degree of self-renewal than their wildtype counterparts, demonstrating that Ronin functions independently of Oct4. (D) Quantification of result in panel C. Bars represent means and standard deviations of triplicate experiments. (E) ZBHTC4.1 [EF1α] ES cells were induced to differentiate by addition of doxycycline, while ZBHTC4.1 [EF1α-Ronin] ES cells ectopically expressing Ronin did respond to doxycyclin only minimally and did not differentiate. (F) Quantification of panel (E).

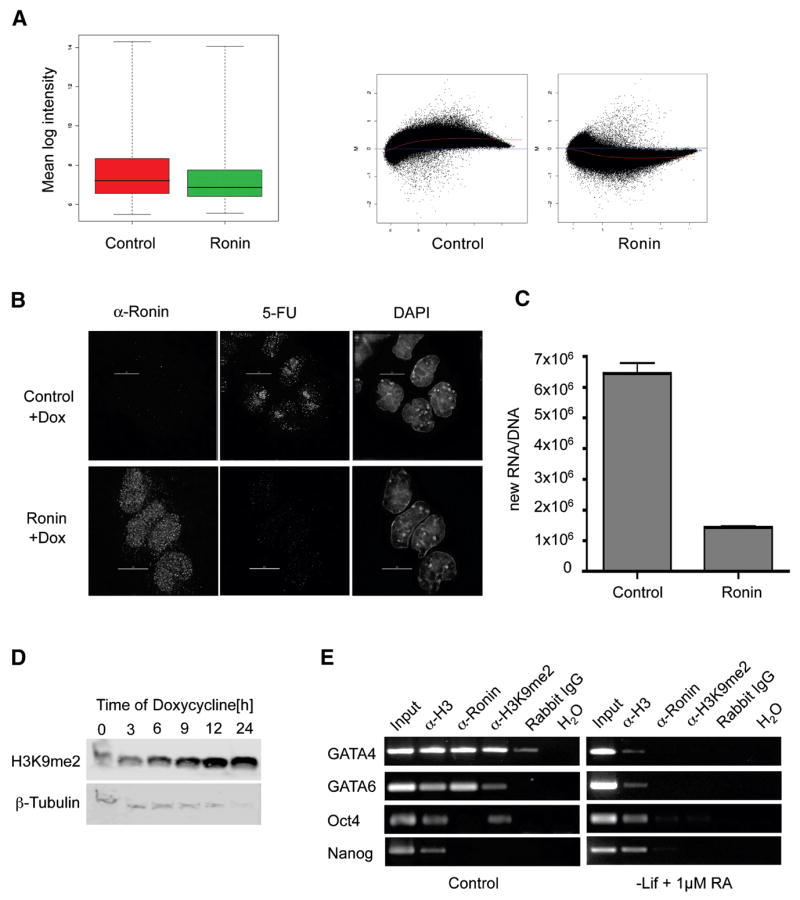

Figure 6. Ronin acts as a transcriptional repressor and epigenetic modulator.

(A, left) Box plots showing results of microarray analysis of control ES cells and ES cells 24 hours after transfection with pEF1α-hRonin-Flag. Each box represent median and 75th and 25th percentile values. Comparison of the absolute quantities of hybridization (right) indicate that Ronin acts as a repressor of a broad range of genes. (B) Confocal images of 5-fluorouridine (5-FU) staining of newly transcribed RNA after induction of Ronin expression in a Ronin-inducible cell line, bar = 10 μm. (C) Quantification of 3H-Uridine incorporation into newly transcribed RNA of control A172loxP cells and A172LP-Ronin-Flag cells after induction with 1 μg/ml doxycycline. Bars show means (and standard deviations) of triplicate experiments. (D) Western blot analysis of H3K9me2 methylation. Induction of Ronin expression by doxycycline led to increased H3K9me2 methylation over time. (E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation and PCR of genomic regions containing the 3x sequence upstream of Gata4 and Gata6. Undifferentiated (control) ES cells showed enrichment for both Ronin and H3K9me2, which was lost after induction of differentiation. In addition Ronin binds the Oct4 promoter region which contains the 3x sequence but not the Nanog promoter which does not contain the 3x sequence.

To determine if knockdown of Oct4 affects the expression of Ronin, we performed siRNA experiments in which Oct4 was rapidly downregulated by day 3 while Ronin was upregulated by comparison with the control. When siRNAs against both genes were tested Ronin was downregulated one day ealier than Oct4 (Figure 4B). These results suggest that Ronin may act independently of Oct4 and Nanog to maintain pluripotency, an interpretation supported by the findings of Ivanova et al. (Figure S5; Ivanova et al. 2005). We wish to point out that Ronin expression was not significantly affected, and even appeared to be slightly upregulated by knockdown of Oct4/Sox2/Nanog, indicating that Ronin may not be regulated at the RNA level as stringently as other pluripotency factors. Functional proof that Ronin-expressing cells can self-renew independently of Oct4 expression came from experiments in which we transfected control and Ronin-expressing cells with siRNA against Oct4. In contrast to controls, the reduction of Oct4 expression had no effect on cell morphology or differentiation (Figure 4C, D). We also stably overexpressed Ronin in the ZBHTc4.1 ES cell line, in which Oct4 expression can be downregulated with use of doxycycline. As in the preceding Oct4 knockdown experiments, we found that ES cells from this line continue to self-renew and are capable of forming colonies after downregulation of Oct4 (Figure 4E, F, S6). Hence, to maintain pluripotency, Ronin does not require the LIF/Stat3 pathway and may not depend on direct interaction with the Oct4/Sox2/Nanog axis.

Ectopic Expression of Ronin Is Tumorigenic

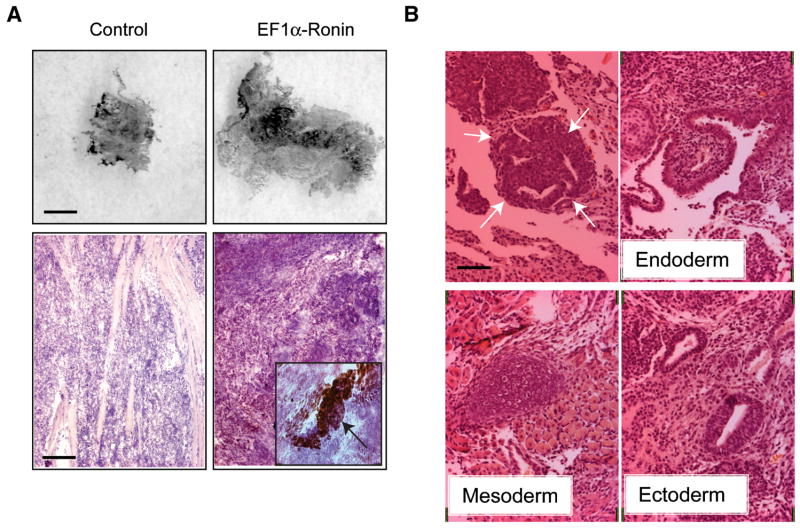

If Ronin truly acts as an antidifferentiation factor in ES cells, its overexpression should be associated with strong tumorigenicity. Thus, to assess teratocarcinoma formation, we injected control ES cells and EF1α-Ronin ES cell lines into the hind-leg quadriceps muscle of SCID immunocompromised mice. Animals injected with control ES cells displayed teratocarcinomas of the expected size by 17 days, while those injected with EF1α-Ronin had substantially larger tumors (2.8 cm vs. 1.8) in two independent experiments, suggesting that increased Ronin activity triggers expansion of the stem cell pool, leading to more robust teratocarcinoma formation prior to differentiation (Figure 5A). Histologic examination of the teratocarcinomas derived from both control ES and Ronin-expressing EF1α-Ronin ES cells revealed differentiation into all three germ layers in both contexts (Figure 5B). However, we noticed a substantial number of undifferentiated cell clusters in the EF1α-Ronin tumors that resembled embryonic carcinoma cells (Figure 5B, top left). This impression was supported by immunostaining results indicating Oct4-positive cell clusters among the EF1α-Ronin ES cells but not the control ES cell line (Figure 5A, bottom panels). Thus, the enhanced tumorigenicity of ES cells constitutively expressing Ronin appears to stem from the antidifferentiation effects of this factor, supporting its candidacy as a key regulator of the pluripotent state.

Figure 5. Ectopic expression of Ronin is tumorigenic.

(A) Immunohistochemical staining of Oct4 in teratocarcinoma sections. Tumors formed by EF1α-Ronin ES cells after injection into immunocompromised mice were much larger than those formed by R1 control cells (top) and more clusters of Oct4-positive cells were present (bottom), insert: 40x magnification of typical Oct4-positive cell cluster in EF1α-Ronin derived tumor, bar (top) = 0.5 cm, bar (bottom) = 0.1 mm (B) H&E staining of EF1α-Ronin teratocarcinoma sections. EF1α-Ronin ES cells were capable of differentiating into all three germ layers, as were their wild-type counterparts (data not shown), white arrows indicate cluster of undifferentiated cells, bar = 50 μm.

Ronin Is a Transcriptional Repressor That Acts Through a Multimeric Protein Protein Complex Containing HCF-1

How does Ronin maintain the pluripotency of ES cells? The most plausible mechanism, based on Ronin’s antidifferentiation effects and the epigenetic silencing activity of other THAP domain proteins (Roussigne et al., 2003; Mcfarlan et al., 2005), is transcriptional repression of multiple genes that are either directly or indirectly involved in differentiation. To test this hypothesis, we performed gene expression profiling of control ES cells versus ES cells transiently transfected with a Ronin-overexpressing construct. This comparison (Figure 6A) showed a striking repression of the transcriptome of Ronin-transfected cells, reflecting either a large decrease in RNA stability or in the synthesis rate of new RNA. To distinguish between these possibilities, we generated a Ronin-inducible cell line by inserting Ronin-encoding cDNA, under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter, upstream of the Hprt locus in A172loxP ES cells and compared the kinetics of RNA transcription in control versus Ronin-expressing cells stained with a bromodeoxyuridine antibody against 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). There was a clear and rapid loss of newly synthesized RNA in cells that overexpressed Ronin (Figure 6B), indicating broad transcriptional repression. This outcome was confirmed by the results of a 3H-uridine pulse-chase incorporation assay (Figure 6C). Finally, Western blot analysis to detect histone H3 dimethylation at lysine 9 (H3K9me2), a reliable marker of chromatin-mediated gene repression, showed a large and rapid increase in the methylation of this protein over time in our Ronin-inducible cell line (Figure 6D). We further tested the ability of Ronin to bind to its target sequence in undifferentiated ES cells. Evidence for direct repression of genes involved in differenitation is provided in Figure 6E, which shows that Ronin binds to the 3x sequence present in the promoter regions of GATA4 and GATA6. Both of these genes show H3K9 methylation in the same region, and neither gene is transcribed in ES cells. After induction of differentiation, GATA4 and GATA6 are no longer bound by Ronin, and their H3K9 methylation is diminished. Interestingly, we also identified a putative DNA binding sequence for Ronin in the promoter region of Oct4, and indeed Ronin did bind to this region, but only in differentiated ES cells; Nanog did not possess a similar binding sequence and was not bound by Ronin (Figure 6E). These observations strengthen the argument that Ronin suppresses gene expression in ES cells by directly binding to key genetic loci and recruiting epigenetic modifiers.

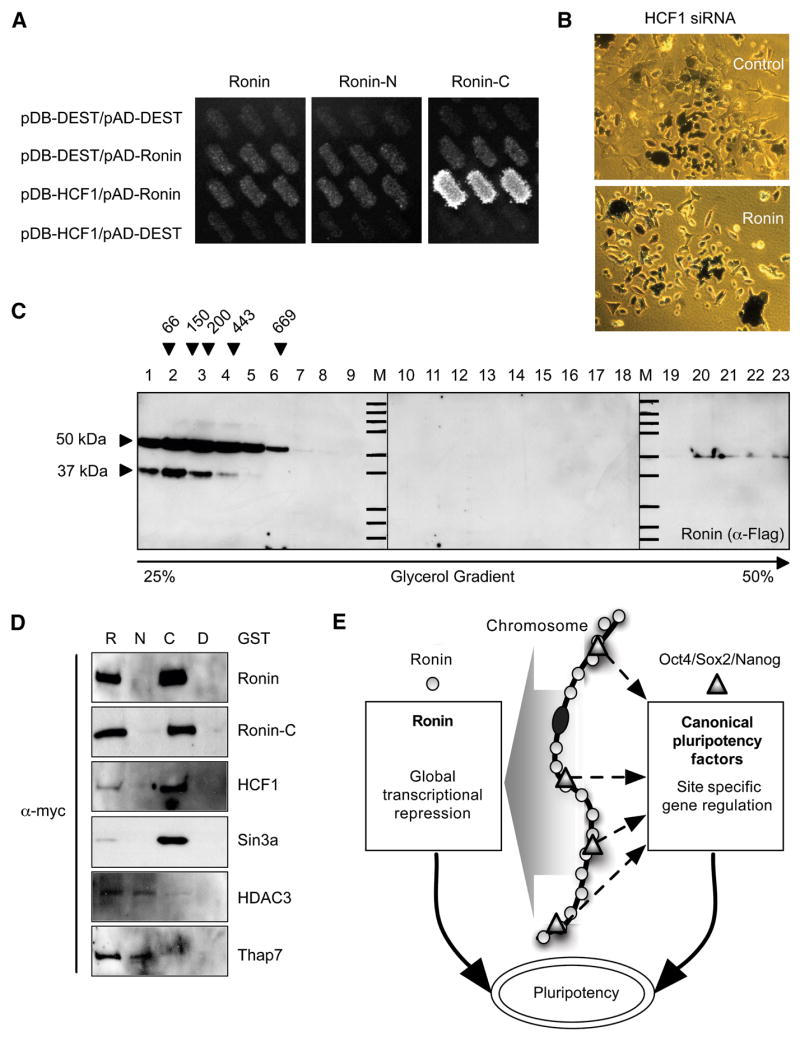

To pursue the idea that Ronin exerts its antidifferentiation effects through epigenetic silencing of gene expression, we devised an immunoprecipitation strategy to identify protein complexes associated with FLAG-tagged Ronin in ES cells. Putative interaction partners were separated by SDS gel electrophoresis and the protein bands subjected to protein tandem mass spectometry analysis. Of 80 candiate proteins, 32 were selected for further evaluation by a directional yeast two-hybrid system. In this approach, full-length Ronin as well as two truncated forms carrying the N-terminus (Ronin-N) or the C-terminus (Ronin-C) were tested for their ability to bind directly to selected putative interaction partners (Figure 7A). The only direct interaction that was identified was between Ronin-C and host cell factor 1 (HCF-1). Retrospective analysis of the Ronin sequence (not shown) revealed a previously described HCF-1 interaction motif (Freiman and Herr, 1997) at the C-terminus of the molecule, making this protein a likely direct target of Ronin. To confirm that HCF-1 is indeed a functional target for Ronin, we performed HCF-1 knockdown experiments in ES cells ectopically expressing Ronin. Knockdown of this gene in both, wild-type and Ronin overexpressing ES cells generated the same phenotype, suggesting that Ronin expression cannot compensate for loss of HCF-1 and hence that Ronin and HCF-1 are functionally related with respect to self-renewal (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Ronin binds directly to HCF-1 and is associated with a very large protein complex.

(A) Directional yeast two-hybrid approach to detect direct interaction of Ronin, Ronin-C and Ronin-N with candidate interacting proteins identified by mass spectometry. Direct interaction of Ronin-C with HCF-1 is represented by growth of cotransfected MAV103 yeast on 50 mM 3AT-containing plates (AD = activation domain, DB = DNA binding domain). (B) Downregulation of HCF-1 by siRNA shows the same phenotype in control ES cells and Ronin ectopically expressing ES cells. (C) Anti-Ronin-Flag Western blot of glycerol gradient fractions of EF1α-Ronin ES cell nuclear extracts purified with wheat germ agglutinin beads. Ronin is present in the first 5 fractions and in fractions 20 to 23 with a peak in 20. Comparison with the elution peaks of protein standards with known sizes (top) demonstrates that Ronin is involved in a very large protein complex. (D) Western blot of Myc-tagged proteins after GST immunoprecipitation. Ronin interacts via its C-terminus with itself, HCF-1 and Sin3A and via its N-terminus with HDAC3 and Thap7. R, Ronin; C, Ronin C-terminus; N, Ronin N-terminus; D, empty destination vector. (E) Proposed model for the mechanism of Ronin function. In contrast to the site specific gene modulatory activity of canonical pluripotency factors (e.g., Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog), Ronin appears to repress transcription more broadly to ensure the maintenance of ES cell pluripotency.

Wysocka and co-workers (Wysocka et al. 2003) isolated a multimeric HCF-1-containing protein complex from HeLa cells by taking advantage of the glycoprotein properties of HCF-1. Hence, we applied a similar strategy to purify a Ronin protein complex from EF1α-Ronin ES cells. Comparison with the elution peaks of protein standards of known sizes, detected by Coomassie blue staining, suggested that Ronin functions within a very large (>2 MDa) protein complex (Figure 7C). To identify some of the components of this complex, we selected the same set of proteins used for the yeast two-hybrid evaluation and modified them for the use in cotransformation assays. Thus, 293 cells were cotransfected with GST-tagged variants of Ronin, Ronin-C or Ronin-N and with Myc-tagged variants of the putative interaction partners. Using this strategy, we confirmed the binding of Ronin to HCF-1 via the C-terminus. Other confirmed protein interaction partners (Figure 7D) were Ronin itself (via homodimerization through the C-terminus); THAP7, another THAP domain protein (via heterodimerization through the N-terminus); and Sin3A (C-terminus) and HDAC3 (N-terminus) -all factors associated with transcriptional repression or histone modifications. We therefore suggest that Ronin acts through a large HCF-1-containing protein complex that can modulate or repress gene expression over broad regions of the transcriptome.

Discussion

A core set of transcription factors able to maintain the pluripotency of mouse ES cells has been identified over the past 5 years, but the full repertoire of factors required for maintenance of the undifferentiated state and for self-renewal remains to be discovered. In this study, we demonstrate that Ronin, a THAP domain protein targeted by Caspase-3, is required for normal murine embryogenesis, can sustain the pluripotency of mouse ES cells independently of the LIF/Stat3 pathway and can partly compensate for the loss of Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog. These findings support the candidacy of Ronin as a novel pluripotency factor with functions that appear to differ from those of canonical pluripotency factors.

Like Oct4 and Sox2, but not Nanog, Ronin was highly expressed in the ooplasm of mature oocytes (Okamoto et al., 1990; Rosner et al., 1990; Scholer et al., 1990; Avilion et al., 2003; Chambers et al., 2003), which may indicate its involvement in oocyte maturation. After fertilization, Ronin was found throughout the zygote, suggesting that it is essential for establishing the zygotic stage of the embryo. Indeed, the Ronin gene begins to be expressed at the 2-cell stage of embryonic development, where zygotic gene transcription is generally initiated. The highest levels of Ronin expression occurred during the morula stage followed by rapidly decreasing expression in the ICM and the implanting blastocyst, where it was barely detectable. This expression pattern indicates differential requirements for Ronin during early embryogenesis and in ES cells, a notion supported by the apparent ability of the Ronin protein to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Whether the nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins have different functions remains an open question; nonetheless, our data strongly suggest that Ronin is tightly regulated at the protein level.

Ronin was also expressed in the hippocampus, olfactory region, subventricular zone and cerebellum of the adult brain, suggesting that it fills specific roles in these regions that may be related to specialized requirements for epigenetic and transcriptional regulation, as in ES cells. Otherwise, the Ronin expression level in adult animals was very low or nonexistent, although we cannot rule out the possibility that Ronin may be highly expressed in rare populations of stem or progenitor cells with exceptional needs for plasticity, analogous to expression of the newly recognized Zfx gene in both ES and hematopoietic stem cells (Galan-Caridad et al., 2007). Finally, Ronin transcription was turned off relatively quickly after induction of ES cell differentiation, but the disappearance of Ronin mRNA was delayed by comparison to the mRNA of other factors, such as DPPA4 (Sperger et al., 2003), suggesting that Ronin may be required not only during the very early stages of embryonic development, but also during the differentiation stage. The results of our Ronin lacZ reporter assay argue strongly for selective expression of Ronin in a very limited number of cell types. If confirmed, this expression pattern might explain how Ronin has escaped detection by expression profiling of genes important for ES cell function and why it is represented by only marginal levels of expression in available databases (e.g., NIH SAGE).

Our Ronin knockout mouse embryo reiterates the phenotype of Oct4 and Nanog knockout blastocysts (Nichols et al., 1998; Mitsui et al., 2003). That is, while these blastocysts appear grossly unimpaired with regard to morphology, there is no ICM outgrowth, and embryos undergo periimplantation death. Thus, the lethal defect likely resides within the ICM itself, as predicted by the striking similarities with the Oct4 and Nanog knockout phenotypes and the finding that Ronin is an essential protein in ES cells. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out a defect in extraembryonic tissues required for the formation of the ICM. It is noteworthy that the expression pattern of Ronin does not necessarily contradict the lethal phenotype we observed in Ronin knockout embryos. Indeed, Ronin protein is present in the ICM (Figure 1G) and would be expected to function at this stage of development, so that its loss might well be lethal to the blastocyst. Whatever the explanation, our analysis of the Ronin expression pattern and the finding that Ronin knockout produces no phenotype in MEFs clearly indicate that the protein performs very specific functions in ES cells.

Although ES cells do not require Sox2 and Nanog for maintenance of the pluripotent state, at least in some contexts (Chambers et al., 2007; Masui et al., 2007), they do show an absolute dependency on Oct4, whose function cannot be replaced by other pluripotency factors tested to date (Ivanova et al., 2006). Hence, a major finding of our study is the ability of Ronin to override (at least partially) the requirement for Oct4 in the maintenance of pluripotency. To exclude the possibility that a small subfraction of cells might still be capable of undergoing self-renewal even in the absence of Ronin, we conditionally removed the endogenous Ronin allele in ES cells and observed that Ronin knockout seems to lead to rapid cell death. This result could reflect the inability of the tissue culture medium to support propagation of the particular cell type generated by Ronin-deficient ES cells, but this possibility seems unlikely because our medium contains serum and supports all major lineages derived from ES cells. The most plausible explanation is that loss of Ronin activates large blocks of normally repressed genes, whose unscheduled expression leads to programmed cell death. However, we cannot rule out a direct effect of Ronin deficiency on the cell’s apoptotic machinery. Moreover, Ronin was able to sustain the undifferentiated state of cultured ES cells even in the absence of LIF, an essential self-renewal factor that operates through the Jak-Stat pathway (Smith 2001). A lack of complete dependence of Ronin function on canonical pathways was further indicated by its persistent expression upon knockdown of Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog. Taken together, these observations suggest a need to reconsider the prevailing Oct4/Sox2/Nanogcentric view of ES cell pluripotency.

We think it is important that in the teratocarcinoma model, Ronin acts as a tumor-promoting factor. Given that Ronin is expressed in some cells in the adult animal, it may possess a tumor-promoting function as well as the ability to regulate pluripotency. Indeed, the human RONIN gene is located on chromosome 16q22.1, a locus that has been associated with several forms of cancer, including leukemias, squamous cell carcinomas and breast and prostate cancers and RONIN was found to be overexpressed in tumors (Frengen et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2007).

A defining feature of Ronin is its THAP domain (Roussigne et al., 2003a; Roussigne et al., 2003b), whose zinc-finger DNA-binding motif is shared with a large family of cellular factors (more than 100 distinct members) in the animal kingdom. It has been proposed that THAP-containing proteins act at the level of chromatin regulation because of their frequent interaction with chromatin-modifying proteins (Macfarlan et al., 2005; Macfarlan et al., 2006). The DNA sequence recognized by Ronin is unusually long, about 15 bp compared with only 3 or 4 nucleotides for most zinc-finger proteins. This finding agrees with data on Thap1, another THAP domain-containing protein that is responsible for regulating pRB-E2F target genes (Bessiere et al., 2007; Cayrol et al., 2007). However, the DNA sequence recognized by Thap1 differs from the Ronin-binding sequence, suggesting that each THAP domain may recognize a different DNA sequence, an idea supported by recent elucidation of structures within the THAP domain of Thap1 (Bessiere et al., 2007). Among the THAP family members, proteins that interact with chromatin-modifying elements, Thap7 and HIM-17 are perhaps the best characterized. Thap7 associates with both histone tails and HDACs (Macfarlan et al., 2005; Macfarlan et al., 2006), while HIM-17, is involved in recruitment of the methyltransferase activity to histone H3 at lysine 9 (Reddy and Villeneuve, 2004; Bessler et al., 2007).

We hypothesize that Ronin suppresses the activity of multiple genes by binding directly to DNA and then recruiting HCF-1 and thus chromatin-modifying proteins. The components of this large complex are likely to include Set1 (histone H3K4 methyltransferase) and Sin3a (Wysocka et al 2003; Yokoyama et al. 2004), HDAC3 and THAP7, all factors associated with epigenetic modification of chromatin to maintain target genes in a repressed state. The association of HCF-1 with both activating and repressive epigenetic modifications raises the intriguing possibility that Ronin interaction with HCF-1 could introduce conflicting chromatin marks (so-called bivalent domains) at specific sites. Besides its role as a transcriptional regulator, HCF-1 has been linked to regulation of the cell cycle; however, both acute and chronic expression of Ronin in ES as well as somatic cells have at most only a marginal effect on the proliferation of ES cells (Li-Fang Chu, personal communication), making it unlikely that the interaction of Ronin with HCF-1 contributes to cell cycle control. An alternative explanation is that Ronin may affect RNA stability.

We suggest that the Ronin/HCF-1 multimeric protein complex could augment the role of Polycomb group proteins in ES cells (Boyer et al., 2006) by ensuring the quiescence of key developmental genes until they are needed for differentiation. However, we cannot exclude that other proteins may interact directly with Ronin to fulfill critical functions. Our model (Figure 7E) predicts that Ronin acts broadly on transcription in pluripotent cells, in contrast to the canonical pluripotency factors (Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog), which modulate very specific particular genes that are either required for pluripotency or differentiation events. Thus, the major difference between Ronin and other pluripotency factors may lie in the scope of its action. If so, Ronin could be functionally compared in the broadest sense with the C. elegans PIE-1 protein, which globally represses transcription in germ cells as an integral step in its normal function (Blackwell 2004). This model does not exclude the possibility that Ronin and the canonical pluripotency factors might act in parallel, perhaps on the same genes. Indeed, the Ronin DNA-binding sequence (3x) is upstream of many key development genes known to be targets of established pluripotency factors (e.g., GATA4 and GATA6), and seems to bind to those regions of the genome associated with epigenetic silencing marks. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the fact that depending on the differentiation status of ES cells, Ronin can bind to the Oct4 promoter itself. Identification of other key genes recognized by Ronin will help to elucidate the specific functions of this factor.

Our discovery and characterization of Ronin has several implications for the mechanisms that underlie pluripotency. Despite numerous investigations of factors that participate in the control of pluripotency, this state is still defined purely in functional terms. Thus, whether a particular cell is pluripotent (differentiation to all cells in the body), capable of contributing to the germline only (germline transmission), multipotent (differentiation to some but not all cell types) or unipotent (differentiation to a single cell type only) cannot be addressed in molecular terms with any degree of certainty. Our findings identifying Ronin as a novel type of pluripotency factor suggest a new tier of control in addition to the transcriptional circuit now believed to regulate ES cell pluripotency, and contribute importantly to delineation of the role of epigenetic factors in this regulation.

Experimental Procedures

Culture, differentiation, alkaline phosphatase staining and transfection of cells

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), L-Glutamine (Gibco), 100 nM non-essential aminoacids (Gibco) and μ100 M beta-mercaptoethanol (Fluka). Embryonic stem (ES) cells were co-cultured with MEFs (or in 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes) in Knock-Out DMEM (Gibco) containing the same supplements as MEF medium, plus 1000 U/ml LIF (Chemicon). For monolayer differentiation studies using the mpRonin-lacZ reporter ES cell line (clone C) and wild-type (wt) R1 ES cells, cells were plated onto gelatin-coated culture dishes at 6000 cells/cm2 in ES cell medium without LIF and cultured for 3 days. Medium was replaced daily. Embryoid bodies (EB) were formed in hanging drops (20 μl mES medium) seeded with 600 cells and cultured for 3 days without LIF. Differentiation of R1, EF1α-Ronin and EF1α-ΔRonin R1 ES cells, detected by alkaline phosphatase staining, was induced by plating 1000 cells/cm2 and culturing in the absence of LIF for 4 days. For alkaline phosphatase staining, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed for 30 minutes in 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature (RT), washed once in PBS and stained in the dark using the AlkPhosIII Kit (Vector Laboratories), as described by the manufacturer. Plasmids were transfected using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s standard protocol, unless indicated otherwise.

Targeted deletion of the mouse Ronin gene

A targeting vector specific for the mouse Ronin allele was created in a four-step cloning procedure (see Supplementary Experimental Procedures) using the pfrt-loxP plasmid as a backbone (a gift from Dr. James Martin, Texas A&M Institute of Biotechnology). This vector contains loxP sites separated by a multiple cloning site, a PGK-neomycin-resistance cassette (NeoR) flanked by Flp recombinase recognition sites, and a downstream thymidine kinase gene for negative selection. The entire Ronin mRNA coding region was inserted between the loxP sites, which were placed in regions of low homology to create an inducible null genotype (Supplemental Figure 3A). After linearization with AscI, the Ronin targeting vector was introduced into R1 ES cells by electroporation followed by selection in the presence of G418 and ganciclovir; 960 G418- and ganciclovir-resistant colonies were isolated. After screening 56 individual ES cell colonies by PCR analysis, we identified four positive clones, designated Ronin+/f lox; three of these were subsequently microinjected into blastocyst-stage embryos and implanted into pseudopregnant female recipients to generate chimeric mice (Mouse Embryo Manipulation Services at Baylor College of Medicine). After confirming the genotypes of the resulting mice by Southern blotting and PCR analysis of genomic DNA (Supplemental Figure 3B), the mice were crossed with Zp3-Cre transgenic mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Female mice carrying the deleted Ronin allele and Zp3-Cre transgene were then crossed with B6 wild-type males to obtain Ronin+/− (heterozygous) offspring.

Generation of EF1α-Ronin ES Cells

EF1α-Ronin mouse ES cells, in which constitutive, ectopic expression of FLAG-tagged human Ronin could be eliminated by a Cre recombination event, were generated by introducing FLAG tag and loxP sites and the desired restriction sites using PCR, as described in Supplementary Experimental Procedures. The resulting PCR product was ligated into BglII and XbaI sites of the pEF1-luciferase-IRES-Neo vector (a generous gift from David Spencer, BCM), replacing the luciferase gene with the Ronin coding sequence to generate the pEF1-hRonin-Flag-loxP vector. Twenty micrograms of circular vector were linearized with the restriction enzyme, NdeI, and electroporated into 10 × 106 R1 mouse ES cells, which were then grown on a layer of neomycin-resistant MEF feeder cells. Transfectants were selected over a period of 8 to 10 days using 200 μg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen), after which individual ES cell colonies were screened for Ronin expression by Western blot analyses using an antibody against the FLAG epitope (Sigma). Under denaturing conditions, Ronin migrated as a 50 kD protein. A control cell line expressing the pEF1/His/C vector (Invitrogen) was produced in a similar manner using NruI-linearized vector.

Generation of EF1α-ΔRonin ES cells

To eliminate ectopic Ronin expression and generate EF1α-ΔRonin ES cells, EF1α-Ronin ES cells were plated at a density of 3600 cells/10-cm dish and cultured without LIF. After 4 days, cells grown on 10-cm dishes were re-plated at the same density in 15-cm dishes and selected in medium without LIF for 4 more days. Colonies were then selected and expanded on MEF feeder cells in medium supplemented with LIF. After expansion, 5 × 106 cells were plated on MEFs in a 10-cm dish and transfected 4 hours later with a 1:4 mixture of pCMV-GFP (Stratagene) and pSalk-Cre (a kind gift of Dr. Michael Kyba). After culturing for 18 hours, 5 × 106 GFP positive cells were sorted by fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS; BD Biosciences FACSaria) and 2,500 green fluorescent cells/cm2 were plated on MEFs in a 10-cm dish. After passaging twice, the GFP signal had faded completely, indicating that Cre activity was absent. Passaged cells were then plated at 1,000 cells/cm2 and cultured for 9 days to allow colonies to form. Selected colonies were expanded and genotyped for successful elimination of Ronin by Cre-mediated recombination. Thirty clones were genotyped using the oligos MAD221 (5′-CCG GCC TTA TTC CAA GCG GC-3′) and MAD224 (5′-CTG ACT GCT GTC TAC AGT GGC CTG-3′). A second PCR, using oligos MAD221 and MAD222 (5′-AGT CAG GCT CCG GGA TCC GTA CAG -3′), was performed to exclude the presence of expanded mixed cultures containing non-revertant EF1α-Ronin ES cells. After culturing in the absence of LIF for 4 days, as described, six of these clones were shown to differentiate in a manner similar to wt R1 cells, three of which generated chimeric mice following injection into blastocysts, confirming pluripotency. Chimeric mice were identified at 3 weeks of age on the basis of coat color.

siRNA knockdown experiments

To induce differentiation by knocking down oct3/4, R1 cells (1 × 105/well) or EF1α-Ronin ES cells (2 × 105/well), plated in 6-well plates (10 cm2/well), were transfected with Smart Pool siRNA oct3/4 (Dharmacon, M-046256-00-0005) using 5 μl of Lipofectamine2000 and following the siRNA transfection protocol for D3 cells (Invitrogen). Briefly, Lipofectamine2000 and siRNA were diluted in 250 μl OptiMEM, incubated for 15 minutes, mixed, incubated for an additional 15 minutes, and then added to cells. GFP duplex siRNA (Dharmacon) served as a negative control in a parallel experiment. Cell morphology was assessed by alkaline phosphatase staining after 3 days. Knockdown of HCF-1 was accomplished with SMARTpool siRNA HCFC1 (Dharmacon, M-051186-00-0005).

5-Fluorouridine staining of newly transcribed RNA

A172loxP or A172LP-Ronin-FLAG cells (1.5 × 105 cells/well) were plated on an MEF feeder layer in 2-chamber slides. After 8 hours, Ronin expression was induced with doxycycline (1 μg/ml), and 12 hours later nascent RNA was labeled by incubation with 100 μM 5-fluorouridine (5-FU, Sigma, F5130) for 1 hour, as described by Boisvert et al. (2000). 5-FU was detected with an anti-BrdU primary antibody (Sigma, 1:500) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, 1:1000). Ronin was detected with the Ronin antiserum, G4275 (1:2000), and the secondary antibody, AlexaFluor 594 (Molecular Probes, 1:1000). Cells were mounted in Vectashield Mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and examined by fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss 63x/1.40 objective. Images were deconvoluted using the Resolve3D software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R.R. Behringer, M.K. Brenner, A. Antebi, R. Stewart and M.A. Goodell for critical reading of the manuscript and A. Crane for some technical assistance. We thank Dr. Hitoshi Niwa for providing us with ZBHTc4.1 ES cells. This work was supported by the Lance Armstrong Foundation (T.P.Z.), the Gillson Longenbaugh Foundation (T.P.Z.), the Tilker Medical Research Foundatiom (T.P.Z.), the Diana Helis Henry Medical Research Foundation (T.P.Z.), the Huffington Foundation (T.P.Z.) and by the NIH (grant R01 EB005173-01, P20 EB007076 and P01 GM81627).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Avilion AA, Nicolis SK, Pevny LH, Perez L, Vivian N, Lovell-Badge R. Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes Dev. 2003;17:126–140. doi: 10.1101/gad.224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessiere D, Lacroix C, Campagne S, Ecochard V, Guillet V, Mourey L, Lopez F, Czaplicki J, Demange P, Milon A, et al. Structure-function analysis of the thap-zinc finger of thap1, a large C2CH DNA-binding module linked to RB/E2F pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessler JB, Reddy KC, Hayashi M, Hodgkin J, Villeneuve AM. A role for Caenorhabditis elegans chromatin-associated protein HIM-17 in the proliferation vs. meiotic entry decision. Genetics. 2007;175:2029–2037. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell TK. Germ cells: finding programs of mass repression. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R229–R230. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Plath K, Zeitlinger J, Brambrink T, Medeiros LA, Lee TI, Levine SS, Wernig M, Tajonar A, Ray MK, et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006;441:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brons IG, Smithers LE, Trotter MW, Rugg-Gunn P, Sun B, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, Howlett SK, Clarkson A, Ahrlund-Richter L, Pedersen RA, Vallier L. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature. 2007;448:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature05950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayrol C, Lacroix C, Mathe C, Ecochard V, Ceribelli M, Loreau E, Lazar V, Dessen P, Mantovani R, Aguilar L, Girard JP. The THAP-zinc finger protein THAP1 regulates endothelial cell proliferation through modulation of pRB/E2F cell-cycle target genes. Blood. 2007;109:584–594. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-012013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M, Nichols J, Lee S, Tweedie S, Smith A. Functional expression cloning of nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2003;113:643–655. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers I, Silva J, Colby D, Nichols J, Nijmeijer B, Robertson M, Vrana J, Jones K, Grotewold L, Smith A. Nanog safeguards pluripotency and mediates germline development. Nature. 2007;450:1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/nature06403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita J, Crane AM, Souza MK, Dejosez M, Kyba M, Flavell RA, Thomson JA, Zwaka TP. Caspase activity mediates the differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell . 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.04.001. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiman RN, Herr W. Viral mimicry: Common mode of association with HCF by VP16 and the cellular protein LZIP. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3122–3127. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frengen E, Rocca-Serra P, Shaposhnikov S, Taine L, Thorsen J, Bepoldin C, Krekling M, Lafon D, Aas KK, El Moneim AA, et al. High-resolution integrated map encompassing the breast cancer loss of heterozygosity region on human chromosome 16q22.1. Genomics. 2000;70:273–285. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan-Caridad JM, Harel S, Arenzana TL, Hou ZE, Doetsch FK, Mirny LA, Reizis B. Zfx controls the self-renewal of embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 2007;129:345–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlard M, Berlivet S, Probst AV, Quivy JP, Hery P, Almouzni G, Gerard M. CAF-1 is essential for heterochromatin organization in pluripotent embryonic cells. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova N, Dobrin R, Lu R, Kotenko I, Levorse J, DeCoste C, Schafer X, Lun Y, Lemischka IR. Dissecting self-renewal in stem cells with RNA interference. Nature. 2006;442:533–538. doi: 10.1038/nature04915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahan BW, Ephrussi B. Developmental potentialities of clonal in vitro cultures of mouse testicular teratoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970;44:1015–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klochendler-Yeivin A, Fiette L, Barra J, Muchardt C, Babinet C, Yaniv M. The murine SNF5/INI1 chromatin remodeling factor is essential for embryonic development and tumor suppression. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:500–506. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, Guenther MG, Levine SS, Kumar RM, Chevalier B, Johnstone SE, Cole MF, Isono K, et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlan T, Kutney S, Altman B, Montross R, Yu J, Chakravarti D. Human THAP7 is a chromatin-associated, histone tail-binding protein that represses transcription via recruitment of HDAC3 and nuclear hormone receptor corepressor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7346–7358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlan T, Parker JB, Nagata K, Chakravarti D. Thanatos-associated protein 7 associates with template activating factor-Ibeta and inhibits histone acetylation to repress transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:335–347. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maherali N, Sridharan R, Xie W, Utikal J, Eminli S, Arnold K, Stadtfeld M, Yachechko R, Tchieu J, Jaenisch R, et al. Directly Reprogrammed Fibroblasts Show Global Epigenetic Remodeling and Widespeard Tissue Contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui S, Nakatake Y, Toyooka Y, Shimosato D, Yagi R, Takahashi K, Okochi H, Okuda A, Matoba R, Sharov AA, et al. Pluripotency governed by Sox2 via regulation of Oct3/4 expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:625–635. doi: 10.1038/ncb1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Zsebo K, Hogan BL. Derivation of pluripotential embryonic stem cells from murine primordial germ cells in culture. Cell. 1992;70:841–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, Segawa K, Murakami M, Takahashi K, Maruyama M, Maeda M, Yamanaka S. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 2003;113:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, Scholer H, Smith A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H. Open conformation chromatin and pluripotency. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2671–2676. doi: 10.1101/gad.1615707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Okazawa H, Okuda A, Sakai M, Muramatsu M, Hamada H. A novel octamer binding transcription factor is differentially expressed in mouse embryonic cells. Cell. 1990;60:461–472. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen RA. Potency, lineage and allocation in preimplantation mouse embryos. In: Rossant J, Pedersen RA, editors. Experimental approaches to mammalian embryonic development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1986. pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KC, Villeneuve AM. C. elegans HIM-17 links chromatin modification and competence for initiation of meiotic recombination. Cell. 2004;118:439–452. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner MH, Vigano MA, Ozato K, Timmons PM, Poirier F, Rigby PW, Staudt LM. A POU-domain transcription factor in early stem cells and germ cells of the mammalian embryo. Nature. 1990;345:686–692. doi: 10.1038/345686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussigne M, Cayrol C, Clouaire T, Amalric F, Girard JP. THAP1 is a nuclear proapoptotic factor that links prostate-apoptosis-response-4 (Par-4) to PML nuclear bodies. Oncogene. 2003a;22:2432–2442. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussigne M, Kossida S, Lavigne AC, Clouaire T, Ecochard V, Glories A, Amalric F, Girard JP. The THAP domain: a novel protein motif with similarity to the DNA-binding domain of P element transposase. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003b;28:66–69. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeftner S, Sengupta AK, Kubicek S, Mechtler K, Spahn L, Koseki H, Jenuwein T, Wutz A. Recruitment of PRC1 function at the initiation of X inactivation independent of PRC2 and silencing. Embo J. 2006;25:3110–3122. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholer HR, Ruppert S, Suzuki N, Chowdhury K, Gruss P. New type of POU domain in germ line-specific protein Oct-4. Nature. 1990;344:435–439. doi: 10.1038/344435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. The battlefield of pluripotency. Cell. 2005;123:757–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AG. Embryo-derived stem cells: of mice and men. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:435–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperger JM, Chen X, Draper JS, Antosiewicz JE, Chon CH, Jones SB, Brooks JD, Andrews PW, Brown PO, Thomson JA. Gene expression patterns in human embryonic stem cells and human pluripotent germ cell tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13350–13355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235735100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem celll from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:652–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesar PJ, Chenoweth JG, Brook FA, Davies TJ, Evans EP, Mack DL, Gardner RL, McKay RD. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature05972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyatt LM, Duwel A, Smith AG, Rathjen PD. The responsiveness of embryonic stem cells to alpha and beta interferon provides the basis of an inducible expression system for analysis of developmental control genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7971–7976. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka J, Myers MP, Laherty CD, Eisenman RN, Herr W. Human Sin3 deacetylase and trithorax-related Set1/Ash2 histone H3-K4 methyltransferase are tethered together selectively by the cell-proliferation factor HCF-1. Genes Dev. 2003;17:896–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.252103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka S. Strategies and New Developments in the Generation of Patient-Specific Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(39):49. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan B, Yang X, Lee TL, Friedman J, Tang J, Van Waes C, Chen Z. Genome-wide identification of novel expression signatures reveal distinct patterns and prevalence of binding motifs for p53, nuclear factor-kappaB and other signal transcription factors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R78. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A, Wang Z, Wysocka J, Sanyal M, Aufiero DJ, Kitabayashi I, Herr W, Cleary ML. Leukemia proto-oncoprotein MLL forms a SET1-like histone methyltransferase complex with menin to regulate Hox gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5639–5649. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5639-5649.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Somatic Cells. Science. 2007 doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.