SYNOPSIS

Objectives.

Those exposed to more degrading sexual references in popular music are more likely to initiate intercourse at a younger age. The purpose of this study was to perform a content analysis of contemporary popular music with particular attention paid to the prevalence of degrading and non--degrading sexual references. We also aimed to determine if sexual references of each subtype were associated with other song characteristics and/or content.

Methods.

We used Billboard magazine to identify the top popular songs in 2005. Two independent coders each analyzed all of these songs (n=279) for degrading and non-degrading sexual references. As measured with Cohen's kappa scores, inter-rater agreement on degrading vs. non-degrading sex was substantial. Mentions of substance use, violence, and weapon carrying were also coded.

Results.

Of the 279 songs identified, 103 (36.9%) contained references to sexual activity. Songs with references to degrading sex were more common than songs with references to non-degrading sex (67 [65.0%] vs. 36 [35.0%], p<0.001). Songs with degrading sex were most commonly Rap (64.2%), whereas songs with non-degrading sex were most likely Country (44.5%) or Rhythm & Blues/Hip-Hop (27.8%). Compared with songs that had no mention of sexual activity, songs with degrading sex were more likely to contain references to substance use, violence, and weapon carrying. Songs with non-degrading sex were no more likely to mention these other risk behaviors.

Conclusions.

References to sexual activity are common in popular music, and degrading sexual references are more prevalent than non-degrading references. References to degrading sex also frequently appear with references to other risky behaviors.

During a period when adolescents are forming health attitudes and behaviors that last a lifetime, they are exposed to an enormous amount of electronic media, much of which contains messages relevant to health behaviors. Music now accounts for more than a third of this exposure: on average, adolescents listen to 2.4 hours of music per day, or more than 16 hours per week. There are few limits to youths' access to music: 98% of children and adolescents live in homes with both radios and CD/MP3 players, and 86% of 8- to 18-year-olds have CD/MP3 players in their bedrooms.1 These figures have increased substantially over the past decade.1,2

Current popular music contains more references to sexual activity than any other entertainment medium.3 There is strong theoretical support for the supposition that exposure to such media may lead to early sexual activity.4,5 According to the social learning model, people learn not only by direct experience but also by exposure to modeled and rewarded behavior, such as that represented in popular music.6–8 Music is well known to connect deeply with adolescents and to influence identity development, perhaps more so than any other entertainment medium.4,9–11 Early sexual intercourse and early progression of other sexual behaviors are of concern because of their direct relationship with sexually transmitted infections12–15 and costly, unwanted teenage pregnancies.15–17

Not all sexual content in music is equivalent. One prominent theme represented in media portrayals of sex, described as “degrading sex,”18 involves three particular attributes: (1) one person (usually male) has a seemingly insatiable sexual appetite, (2) the other person (usually female) is objectified, and (3) sexual value is placed solely on physical characteristics.18–21 According to the social learning model, these references in particular may promote early sexual activity. This is because they may encourage youth to play out these roles (sex-driven male and acquiescent female) rather than resolve their true desires and anxieties surrounding sexual activity.5,18 Longitudinal data show that those exposed to more degrading sexual references in popular music are in fact more likely to initiate intercourse at a younger age.4,18

However, to date there has been no systematic content analysis of popular music with special attention paid to degrading sexual references. If indeed these references are associated with early sex, it is important to learn their relative frequency. Furthermore, it is not currently known whether songs with degrading sexual references are more likely to be associated with other characteristics. If, for instance, degrading sexual references are more common in certain musical genres, this might have implications for targeting of prevention programs. Similarly, it would be instructive to know if songs with degrading sexual references also feature other content related to risk-taking behavior and other public health concerns (i.e., substance use and violence).

The purpose of this study was to perform a content analysis of contemporary popular music with particular attention paid to the prevalence of degrading and non-degrading sexual references. Additionally, we aimed to determine if sexual references of each subtype were associated with other song characteristics (i.e., genre and singer gender) and/or other song content (i.e., violence, weapon carrying, and substance use). We hypothesized that songs with degrading sexual references would be common, but that songs with references to non-degrading sex would be more common. We further hypothesized that all sexual references—both degrading and non-degrading—would be more likely to be associated with male singers, with particular genres, and with other sensation-seeking content such as violence and substance use.

METHODS

Song selection

We used Billboard magazine to identify the most popular songs in the U.S. in 2005.22 Billboard annually uses a complex algorithm, integrating data from both sales and airplay to determine the top songs according to exposure. Sales data for this algorithm are compiled by Nielsen SoundScan from merchants representing more than 90% of the U.S. music market, including sales from music stores, direct-to-consumer transactions, and Internet sales and downloads. Billboard's airplay data utilize Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems, which electronically monitors radio stations in more than 120 representative markets across the U.S. Integrating these data, Billboard reported the following youth-relevant lists of popular song titles in 2005: Pop 100 (n=100), Billboard Hot 100 (n=100), Hot Country Tracks (n=60), Hot Rhythm & Blues (R&B)/Hip-Hop Songs (n=100), Hot Rap Tracks (n=25), Mainstream Rock Tracks (n=40), and Modern Rock Tracks (n=40).

Billboard's year-end charts are closed out, meaning that they do not change based on date of access. Taken together, the song titles from the seven charts represent a comprehensive list of popular contemporary music to which young Americans listen. Because some songs were included on more than one chart, the seven charts of 465 song titles included 279 unique songs, which comprised the sample for this study.

Coding procedures

Two trained initial coders independently analyzed the printed lyrics of each song for references to sexual intercourse, violence, and substance use. Codes were assigned on the basis of lyrics alone. We computed Cohen's kappa statistics23 for agreement on each of these measures and judged these values according to the Landis and Koch framework.24 After this initial coding, we employed two new confirmatory coders to independently code each of the items on which the previous coders did not agree (new coders were blinded to prior codes). When the confirmatory coders both agreed with one of the original codes, that code was supported. However, when the confirmatory coders disagreed with each other or agreed with each other but not with one of the initial coders, the item was discussed by the complete research team to achieve a consensus. Using this algorithm, consensus was easily achieved for all scores.

Measures

Sexual activity.

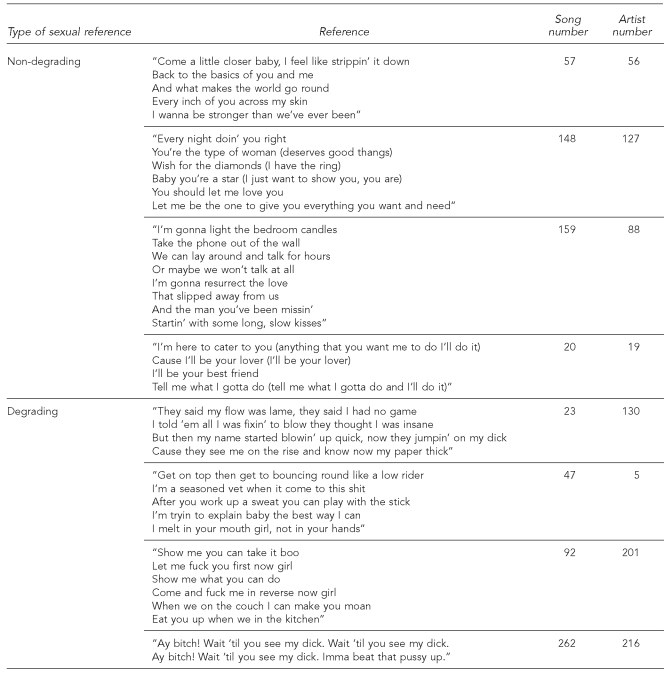

For the outcome variable indicating a reference to sexual activity, our coders assigned two possible values for each song (0 = no sexual activity, 1 = sexual activity). A song was given the value 1 if sexual intercourse was either obvious or strongly implied. For the purposes of this analysis, “sexual intercourse” was defined as penile-vaginal sex, penile-anal sex, or oral sex. A separate variable was used by each coder to classify each song with sexual activity as either degrading or non-degrading. Degrading sexual intercourse was defined as sex that met all three of the following criteria: (1) one person has a large sexual appetite, (2) the other person is objectified, and (3) sexual value is placed solely on physical characteristics. The Figure has examples of degrading and non-degrading sexual references.

Figure.

Examples of sexual references

According to the Landis and Koch framework24 for kappa values, initial coders had moderate agreement on sexual intercourse (κ=0.46) and substantial agreement on degrading vs. non-degrading sexual intercourse scores (κ=0.71). After adjudication, coders agreed on all final codes.

Song characteristics: gender and genre. We determined the gender of the lead singer(s) by examining the CD jacket, viewing relevant websites, and/or listening to the songs. Coders agreed on all gender determinations. Of the 279 songs, 213 were sung by males, 58 by females, and eight by a mixture of males and females.

We used the following standardized approach to uniquely assign one primary genre to each song. First, we used Billboard's website to determine each song's highest position at anytime on each of the Billboard charts we analyzed. Each song was assigned as a primary genre the genre of the specialty chart (i.e., R&B/Hip-Hop, Rap, Rock, or Country) on which it ranked highest, regardless of each song's ranking on the Pop and Hot charts. This was necessary to avoid misclassifying certain highly popular songs. For instance, the singer 50 Cent is an example of someone who is clearly a rap artist. Although some of his songs are very popular and may even fall higher on the Pop chart than the Rap chart, it would be a mistake to classify these songs as Pop, especially alongside true Pop songs such as “Because of You” by Kelly Clarkson. Thus, only songs that never reached any specialty chart but did reach the Pop and/or Hot charts were defined as Pop. We combined the Modern Rock and Mainstream Rock categories into one Rock category because the line between these charts has become less distinct over the past two decades. Using this approach, each song was clearly and uniquely defined as Country (n=61), Pop (n=35), R&B/Hip-Hop (n=55), Rap (n=62), or Rock (n=66).

Other song content.

We also used the coding algorithm described previously to classify songs based on the presence of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or other drugs. Our “other drugs” category included less commonly portrayed substances, such as opiates, hallucinogens, prescription drugs, or nonspecific substances. Coders had at least moderate agreement for each of these outcomes. A more complete description of substance use items is available.25

We also classified each song on a three-point scale (0–2) with regard to violence. We assigned 0 if there was no violence, 1 if there was threatened or actual bodily harm (e.g., “She knocked out my front tooth”), and 2 if there was threatened or actual loss of life due to violence (e.g., “I shot that cop down”). We also assigned a weapon-carrying score on a similar scale: 0 if there were no weapons, 1 if one weapon was mentioned (knife, gun, etc.), and 2 if there were two or more weapons mentioned during the course of the song or if at least one weapon was actually used in a violent act. Inter-rater agreement for each of these measures was at least 74%; more specific agreement values for these measures have been previously published.25

Analysis

We first computed the number and percentage of songs in our sample with references to no sexual intercourse, degrading sexual intercourse, and non-degrading sexual intercourse. We then used Chi-square analyses to determine if there were differences between songs with any sex and songs without sex by (1) gender of the lead singer, (2) primary genre, (3) presence of each episode of substance use, (4) violence, and (5) weapon carrying. We also conducted similar Chi-square analyses comparing songs with degrading sex vs. songs with no sex. Finally, we compared songs with non-degrading sex to songs with no sex. We chose a priori to define statistical significance as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 279 unique songs identified, 103 (36.9%) contained references to sexual intercourse and 176 (63.1%) did not. Of those referencing sexual intercourse, 67 (65.0%) were classified as degrading sex and 36 (35.0%) were classified as non-degrading sex. Examples of degrading and non-degrading sex are found in the Figure.

Although songs with references to degrading sex were more likely than songs with no sexual references to be sung by males (p=0.03), songs with non-degrading sex exhibited an insignificant trend toward being more likely to be sung by females or mixed groups (p=0.07), compared with songs with no sex.

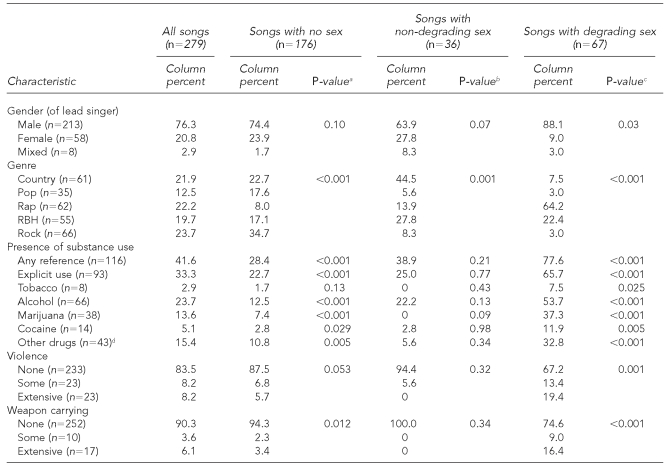

The prevalence of references to different types of sex differed significantly by musical genre (Table). Those songs with degrading sex were most commonly Rap (64.2%) or R&B/Hip-Hop (22.4%). Songs with non-degrading sex, however, were most often Country (44.5%) or R&B/Hip-Hop (27.8%).

Table.

Associations between sexual content and other song characteristics

aP-value is for comparison of songs with no sex vs. songs with sex.

bP-value is for comparison of songs with non-degrading sex vs. songs with no sex.

cP-value is for comparison of songs with degrading sex vs. songs with no sex.

dIncludes opiates, hallucinogens, prescription drugs, and nonspecific substances.

RBH = Rhythm & Blues/Hip-Hop

References to substance use were more common in songs with degrading sex than songs with no sex (77.6% vs. 28.4%, p<0.001). However, substance use references were no more common in songs with non-degrading sex than they were in songs without sex (p=0.21). Similar patterns emerged when considering each substance individually. Compared with songs with no sex, songs with references to degrading sex were more likely to contain any reference to substance use, explicit references to use, or use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or other drugs (Table). However, compared with songs with no sex, songs with non-degrading sexual references were no more likely to contain references to substance use.

Songs with degrading sex had more references to violence and weapon carrying than songs without degrading sex (p=0.001 and p<0.001, respectively). However, songs with references to non-degrading sex were no more likely to reference violence or weapon carrying (p=0.32 and p=0.34, respectively). In fact, none of the 36 songs with references to non-degrading sex contained references to weapon carrying, and only two of the 36 songs (5.6%) contained some reference to violence.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that more than one-third of popular songs portrayed sexual intercourse, and that in about two-thirds of those references the intercourse was degrading. It also showed that genres differ in the types of sex they portray, with Rap having the highest levels of references to degrading sex and Country and R&B/Hip-Hop featuring the highest levels of references to non-degrading sex. Finally, references to substance use, violence, and weapon carrying were associated with songs featuring degrading sex but not with songs containing non-degrading sex.

Our finding that about one-third of popular music contains references to sexual intercourse is important because adolescents listen to popular music about 2.4 hours each day.1 Our results therefore suggest that the average adolescent who listens to a complete cross-section of popular music will spend about 48 minutes each day listening to songs with sexual content, and about 32 minutes each day listening to songs with degrading sexual content. However, our results further suggest that degrading sex is far more common in some genres than others, with the vast majority of degrading sexual references found in two genres (Rap and R&B/Hip-Hop). Interestingly, these happen to be the most popular genres among young people today, regardless of demographic characteristics.1

Future research will need to clarify what impact this exposure has on sexual and other health-related behavior outcomes. Research investigating the relationship between visual media and sex show that the two are related.5,26,27 Although music lacks the visual elements of film and television, there are reasons to believe that references in popular music may be as potent in their relationship with sexual behavior.4,5 Music is known to be highly related to personal identity;11,28,29 young people often model themselves in terms of dress, behavior, and identity after musical figures. In addition, exposure to popular music is vast, with the average adolescent now listening to about 16 hours of music each week.

Our finding that sexual content is frequent in popular music may also have implications for sexual health education. Considering the daily and weekly estimates of music exposure among U.S. youth,1 sexual health lessons are likely to be dwarfed in young people's minds by the lessons they learn through music lyrics' representations of sex. It may therefore be useful for health educators, health professionals, and curriculum designers to become familiar with the messages young people receive about sex in popular music, so that they can effectively respond to those messages. Innovative interventions could identify creative ways of generating doubt in the minds of young people as to the veracity of the sex-related media messages they receive. One way of doing this may be to include media literacy in sexuality education programming, whereby young people learn to analyze and evaluate media portrayals of sex.5,30–32

Our finding that different types of sexual content vary significantly by genre suggests that those exposed to specific musical genres may be at increased risk for the sequelae of early intercourse. This is because previous research has demonstrated an association between degrading sexual content and early sexual intercourse.4,18 Those exposed to proportionally more Rap music, for example, may be at increased risk of early coitarche and sexually transmitted infections. It will be interesting in future research to determine if preference of and/or exposure to certain genres are associated with sexual experience. Additionally, it will be interesting to explore the reasons for differential portrayal of degrading sex in various genres. The sexual content of a genre's songs is likely to be due to a number of social, political, and economic factors, but further research will be necessary to determine more specifically the reasons for these differences. In the meantime, however, this information may be used in developing health promotion materials and campaigns. If indeed those listening to Rap music may be more at risk for sexual risk taking, the principles of social marketing would suggest that it may be useful to choose a Rap artist to be a spokesperson regarding sexual health.

Our finding that songs containing degrading sex more frequently referenced substance use and violence is troubling because substance use can increase both sexual risk taking33,34 and violent behaviors.35 These findings are also concerning because a prior study found that exposure to televised music videos was associated with increased acceptance of rape,36 and it is estimated that over the course of one year, up to 30% of young women have an unwanted sexual experience.37 As alcohol use has been associated with date/acquaintance rape,38 further studies examining the relationship between music lyrics and sexual risk taking will need to consider the mediating effect of musical references to use of substances such as alcohol.

Limitations

Our study was limited in that it focused on one year of popular music, and it is possible that there are temporal trends in references to sex in musical lyrics. As such, it will be important to conduct longer-term analyses of popular music content using rigorous methods. Additionally, it should be noted that coding even the mere presence or absence of sexual activity can be difficult because of the tendency for song lyrics to be highly suggestive but not explicit (Table). It is for this reason that we employed a complex coding methodology and confirmed that our coders reached an adequate level of inter-rater agreement. Still, the challenge of determining sexual content remains an important limitation to this type of work. Finally, it should be emphasized that the purpose of this study was not to link sexual content to actual sexual behavior. This content analysis, however, provides the foundation on which future studies investigating the relationship between exposure to sexual content and actual sexual behavior can be built.

CONCLUSION

Adolescents who listen to contemporary popular music are frequently exposed to sexual content, and this exposure varies widely by genre. Additionally, references to substance use and violence frequently accompany references to degrading sexual intercourse but not to non-degrading sexual intercourse. It will be important to continue surveillance of sexual references in popular music over time and to study the impact of sexual messages in popular music on adolescent sexual behavior.

Acknowledgments

Brian Primack was supported in part by a K-07 career development award from the National Cancer Institute (K07-CA114315), a Physician Faculty Scholar Award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and a grant from the Maurice Falk Foundation. The authors thank Mary V. Carroll, Aaron A. Agarwal, and Dustin Wickett for assistance with data management, and Stephen Martino, PhD, for his editorial input.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rideout V, Roberts D, Foehr U. Generation M: media in the lives of 8–18 year-olds. Menlo Park (CA): Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts DF, Henriksen L, Christenson PG. Substance use in popular movies and music. Washington: Office of National Drug Control Policy, Department of Health and Human Services (US); 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardun CJ, L'Engle KL, Brown JD. Linking exposure to outcomes: early adolescents' consumption of sexual content in six media. Mass Commun Soc. 2005;8:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JD, L'Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C. Sexy media matter: exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicts black and white adolescents' sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1018–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escobar-Chaves SL, Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Low BJ, Eitel P, Thickstun P. Impact of the media on adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviors. Pediatrics. 2005;116:303–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentive perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice. San Francisco: Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller NE, Dollard J. Social learning and imitation. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett JJ. Adolescents' uses of media for self-socialization. J Youth Adolesc. 1995;24:519–33. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christenson PG, Roberts DF. It's not only rock & roll: popular music in the lives of adolescents. Kresskill (NJ): Hampton Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mark A. Adolescents discuss themselves and drugs through music. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1986;3:243–9. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(86)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niccolai LM, Ethier KA, Kershaw TS, Lewis JB, Meade CS, Ickovics JR. New sex partner acquisition and sexually transmitted disease risk among adolescent females. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:216–23. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finer LB, Darroch JE, Singh S. Sexual partnership patterns as a behavioral risk factor for sexually transmitted diseases. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:228–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Succop PA, Ho GY, Burk RD. Mediators of the association between age of first sexual intercourse and subsequent human papillomavirus infection. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E5. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edgardh K. Sexual behaviour and early coitarche in a national sample of 17 year old Swedish girls. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:98–102. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humblet O, Paul C, Dickson N. Core group evolution over time: high-risk sexual behavior in a birth cohort between sexual debut and age 26. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:818–24. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000097102.42149.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buston K, Williamson L, Hart G. Young women under 16 years with experience of sexual intercourse: who becomes pregnant? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:221–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martino SC, Collins RL, Elliott MN, Strachman A, Kanouse DE, Berry SH. Exposure to degrading versus nondegrading music lyrics and sexual behavior among youth. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e430–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gow J. Reconsidering gender roles on MTV: depictions in the most popular music videos of the early 1990s. Commun Rep. 1995;9:151–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seidman SA. An investigation of sex-role stereotyping in music videos. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1992;36:209–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward LM. Talking about sex: common themes about sexuality in prime-time television programs children and adolescents view most. J Youth Adolesc. 1995;24:595–615. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Billboard. Billboard 2005 year in music. [cited 2007 Mar 26]. Available from: URL: http://www.billboard.com/bbcom/yearend/2005/index.jsp.

- 23.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Primack BA, Dalton MA, Carroll MV, Agarwal AA, Fine MJ. Content analysis of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs in popular music. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:169–75. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashby SL, Arcari CM, Edmonson MB. Television viewing and risk of sexual initiation by young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:375–80. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Kunkel D, Hunter SB, et al. Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e280–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1065-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keen AW. Using music as a therapy tool to motivate troubled adolescents. Soc Work Health Care. 2004;39:361–73. doi: 10.1300/j010v39n03_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Took KJ, Weiss DS. The relationship between heavy metal and rap music and adolescent turmoil: real or artifact? Adolescence. 1994;29:613–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thoman E. The Center for Media Literacy. 2003. Skills and strategies for media education. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buckingham D. Media education: literacy, learning, and contemporary culture. Malden (MA): Blackwell Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Primack BA, Gold MA, Switzer GE, Hobbs R, Land SR, Fine MJ. Development and validation of a smoking media literacy scale. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:369–74. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rome ES, Rybicki LA, Durant RH. Pregnancy and other risk behaviors among adolescent girls in Ohio. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:50–5. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staton M, Leukefeld C, Logan TK, Zimmerman R, Lynam D, Milich R, et al. Risky sex behavior and substance use among young adults. Health Soc Work. 1999;24:147–54. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stafstrom M. Kick back and destroy the ride: alcohol-related violence and associations with drinking patterns and delinquency in adolescence. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2007;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Brown JD. Music videos, pro wrestling, and acceptance of date rape among middle school males and females: an exploratory analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:185–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rickert VI, Wiemann CM, Vaughan RD, White JW. Rates and risk factors for sexual violence among an ethnically diverse sample of adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:1132–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.12.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rickert VI, Wiemann CM, Vaughan RD. Disclosure of date/acquaintance rape: who reports and when. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]