Abstract

Apolipoprotein (apo) B is essential for the assembly and secretion of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins made by the liver. As the sole protein component in LDL, apoB is an important determinant of atherosclerosis susceptibility and a potential pharmaceutical target. Single-chain antibodies (sFvs) are the smallest fragment of an IgG molecule capable of maintaining the antigen binding specificity of the parental antibody. In the present study, we describe the cloning and construction of two intracellular antibodies (intrabodies) to human apoB. We targeted these intrabodies to the endoplasmic reticulum for the purpose of retaining nascent apoB within the ER, thereby preventing its secretion. Expression of the 1D1 intrabody in the apoB-secreting human hepatoma cell line HepG2 resulted in marked reduction of apoB secretion. This study demonstrates the utility of an intrabody to specifically block the secretion of a protein determinant of plasma LDL as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of hyperlipidemia.

Keywords: Single-chain antibodies, apoB, lipoproteins, HepG2 cells

ApoB is essential for the assembly and secretion of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins made by the liver and intestine. There are two forms of apoB; apoB100 is produced exclusively in the liver of mammals, whereas apoB48 is produced in the intestine of most mammals including man and both the intestine and liver of mice and rats. ApoB100 is a major protein component of plasma VLDL, IDL and LDL, whereas apoB48 is an essential protein component of intestinal chylomicrons and their remnants. The pathologic importance of apoB is that all apoB-containing lipoproteins are atherogenic, especially LDL. As the sole protein component in LDL, apoB100 is an important determinant of atherosclerosis susceptibility and thus a potential pharmaceutical target for lowering atherogenic lipoproteins.

An important lipid-lowering strategy is to block the production or secretion of apoB-containing lipoproteins. A common approach to accomplish this is to inhibit the activity of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP), an obligate component for assembly of apoB-containing lipoproteins and several MTP inhibitors have been developed for reducing apoB production [1]. An alternative approach is the direct targeting of apoB itself. To date, this has been accomplished by the down regulation of apoB mRNA by ribozymes, siRNAs and antisense oligonucleotides targeting apoB mRNA to lower apoB levels [2-5].

In this communication, we explore an alternative strategy to down-regulate apoB production using single-chain apoB-specific antibodies. Intracellular single-chain antibodies, or “intrabodies,” are an approach to selectively knock-out the function of a desired cellular target protein [6, 7]. Single-chain antibodies (sFvs) are the smallest fragment of an IgG molecule capable of maintaining the antigen-binding specificity of the parental antibody. sFvs are generated by cloning the heavy chain and light chain variable regions of the antibody genes and joining them by a flexible peptide linker. The sFvs can then be targeted to a variety of subcellular compartments by incorporating protein trafficking signals to direct sFv expression to the endoplasimic reticulum (ER), cytosol, nucleus, lysosomes, or mitochondria [8]. Intrabodies targeted to the ER have been utilized to effectively block the cell surface expression of numerous transmembrane proteins, generating phenotypic knockouts of a variety of receptors involved in oncogenesis and viral infection [6, 7]. Intrabodies have been shown to reduce the shedding of co-transfected viral antigens, but there has been no report to date utilizing intrabodies to block the secretion of an endogenous native cell protein.

Herein, we describe the cloning and construction of two intracellular antibodies to human apoB derived from the 1D1 and 1C4 hybridoma cell lines (the monoclonal antibodies 1D1 and 1C4 recognize apoB epitopes situated between residues 474-539 and 1696-1878, respectively [9, 10]. We further describe the targeting of these intrabodies to the endoplasmic reticulum for the purpose of retaining nascent apoB within the ER, thereby preventing its secretion. Expression of the 1D1 intrabody in the apoB-secreting human hepatoma cell line HepG2 resulted in dramatic and specific reduction of apoB secretion. In addition to its promise as a potential gene therapy tool for the treatment of hyperlipidemia, the 1D1 intrabody displays the versatility of the intrabody strategy, as it is the first such intrabody shown to block the secretion of one of the largest (550kDa) monomeric human proteins known.

Materials and methods

Construction of intracellular antibodies against human apoB

Messenger RNA from 5 × 106 log phase hybridoma cells was isolated using the Micro-Fast Track Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. VK and VH cDNA were generated in a 20 μl reaction from 200ng of mRNA at 42°C using the Gene Amp RNA PCR Core Kit (Perkein Elmer). 1C4 and 1D1 VK cDNA was generated using the primer Mouse JK Rev (5′-ACGTTCTAGAACGTTTGATCTCCAGCTTGGT-3′). 5 μl of the cDNA was PCR amplified for 35 cycles with an annealing temperature of 55°C with Mouse JK Rev and the forward primer Mouse VK For (5′-ACGTAAGCTTGACATTGTGMTSACMCARWCKC-3′). VH cDNA were generated in two separate reactions using either the reverse primer Mouse JH RevA (5′-ACGTTCTAGATGAGGAGACKGTG-3′) or Mouse JH RevB (5′-ACGTTCTAGATGCAGAGACAGTGACCAGAGTCCC-3′). The forward primer Mouse JH For (5′-TTAAGCTTSAGGTSMAGCTKSWGSARTCWGG-3′) was used along with the corresponding reverse primer to PCR amplify VH cDNA. Degeneracies in primers reflect predominant variable bases in published mouse VK and VH sequences of various subclasses (R=A/G, K=G/T, S=G/C, W=A/T, M=A/C) [11]. HindIII and XbaI restriction sites used for cloning are underlined. PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels, extracted, and purified using QIAquick Spin PCR Purification and Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). Isolated products were digested with HindIII and XbaI and ligated into pRc/CMV vector digested with the same enzymes. Multiple clones were sequenced by the Sanger method and subjected to nonredundant nucleotide Blast query to identify unique VK and VH sequences. The kappa and heavy chain segments were then linked by a two-step overlapping PCR reaction. The 1C4 VH was amplified from the pCMV template using Mouse JH For and Mouse JH Linker (5′-GCTCCCACCACCTCCGGAGCCACCGCCACCTGCAGAGACAGTGACCAGAGT-3′). 1D1 VH was amplified using Mouse JH For and JH Linker 2 (5′-GCTCCCACCACCTCCGGAGCCACCGCCACCTGAGGAAGACKGTGASWGWGG-3′). VK were amplified using Mouse VK Link (5′-GGTGGCGGTGGCTCCGGAGGTGGTGGGAGCGGTGGCGGCGGATCTGACATTGTGMTSACMCARWCKSC-3′) and Mouse JK Rev. Gel purified VH-Link and VK-Link were then joined using 1 μl each of VH and VK product with Mouse JH For (5′HindIII) and Mouse JK Rev (3′-XbaI) primers to yield a linked sFv in the form VH-Linker-VK. This product was digested and cloned into HindIII/XbaI sites of pRc/CMV. Clones were screened by sequencing in forward and reverse orientation to confirm faithful linking of the parental VH and VK, and spacer sequence.

Generation of Mammalian Expression Vectors

The mouse IgG heavy chain signal peptide was added to the 5′ end of sFvs using the primers SIGA (5′-CTGGTGGCAGCTCCCAGATGGGTCCTGTCCSAGGTGMAGCTKSWG-3′) and SIGB (TTAAGCTTCATATGGAACATCTGTGGTTCTTCCCTTCTCCTGGTGGCAGCTCCCAGATGGGTCCTGTCC-3′) in sequential PCR steps with Mouse VK Rev. Sequences encoding the influenza hemagglutinin epitope (YPYDVPDYA) and KDEL endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal were added in frame using the 3′primer HAKDEL (5′-TTTTCTAGATTACAGCTCGTCCTTCTCGCTAGCATAATCTGGAACATCATACGGATAACGTTTGATCTCCAGCTTGG-3′) with SIGB. The final construct was cloned into HindIII/XbaI sites in pRc/CMV for transient and stable expression in COS-1 or HepG2 cells.

Cell transfections

Transient cell transfection is performed by using Lipofectamine (GibcoBRL) Kit. Stable transfection of HepG2 cells was carried out by electroporation at the conditions: capacitance, 500 μFarads, and charging voltage, 250 V by using a BioRad Gene Pulser™. Stable transfectants were selected in the presence of 500 μg/ml G418. The antibiotic-resistant clones were maintained in the presence of 250 μg/ml G418. For stable transfection of HepG2 cells, the control cells were a mixture of multiple clones that had been transfected with the empty vector and the intrabody clones were individual ones.

Immunoblot analysis and immunoprecipitation

Western blot analysis was performed on the cell lysate and culture medium as described previously [12].

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described [13]. Cells were cultured on 1 cm glass coverslips to 50% confluence. After being rinsed briefly with ice-cold PBS, the cells were fixed and permeabilized with cold methanol at -20 °C for 10 min. After the fixation, the cells were washed and blocked in 10% nonfat milk in PBS for 30 min. The cells were then incubated with mouse anti-HA in 10% nonfat milk in PBS for 1 h and washed 5 times followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG.

Results and discussion

Cloning and characterization of 1D1 and 1C4 heavy and light chain variable region cDNAs

The hybridoma cell lines 1D1 and 1C4 secrete murine monoclonal antibodies that recognize distinct epitopes of the human apoB molecule [9, 10]. We cultured these cell lines and harvested messenger RNA for use in amplification of heavy chain (VH) and light chain (VK) variable region cDNAs. RNA was reverse transcribed using degenerate 3′ primers designed to hybridize to the more conserved 3′-terminal regions of VH and VK domain genes. cDNAs were then PCR amplified using the same 3′ primer and degenerate 5′ VH and VK primers. The primers included 5′ HindIII and 3′ XbaI restriction sites for cloning. PCR product of the appropriate size (325-350 bp) (Supplementary Fig. 1A) was extracted, digested, and cloned into the vector pRc/CMV for sequence analysis. Comparison of unique nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1) with the Kabat et al.[14] subgrouping system revealed the 1D1 VH (351 bp) belongs to the mouse heavy-chain subgroup II(A), and the VK (324 bp) to the mouse kappa(V) subgroup. The 1C4 VH (354 bp) belongs to mouse heavy-chain subgroup III(D), and the VK (324 bp) to the mouse kappa(V) subgroup. The VH and VK cDNAs were then linked by overlapping PCR to incorporate a nucleotide encoding the (Gly4Ser)3 linker peptide. The linked product was cloned and sequenced to confirm faithful linking of the cDNAs. The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the linked 1D1 and 1C4 sFvs (VH-Linker-VK) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1C and 1D, respectively.

Expression of 1C4 and 1D1 sFvs in COS-1 cells

For expression of the sFvs as intrabodies in mammalian cells, the linked constructs were PCR-modified before reinsertion into the pRc/CMV vector. The sFvs were targeted to the secretory pathway by the in-frame addition of the mouse heavy chain signal sequence upstream of the VH sequence. The influenza hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag for immunodetection, and the SEKDEL endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention sequence [6] for ER retention of the intrabody, were added in frame to the 3′ end of the VK sequence (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

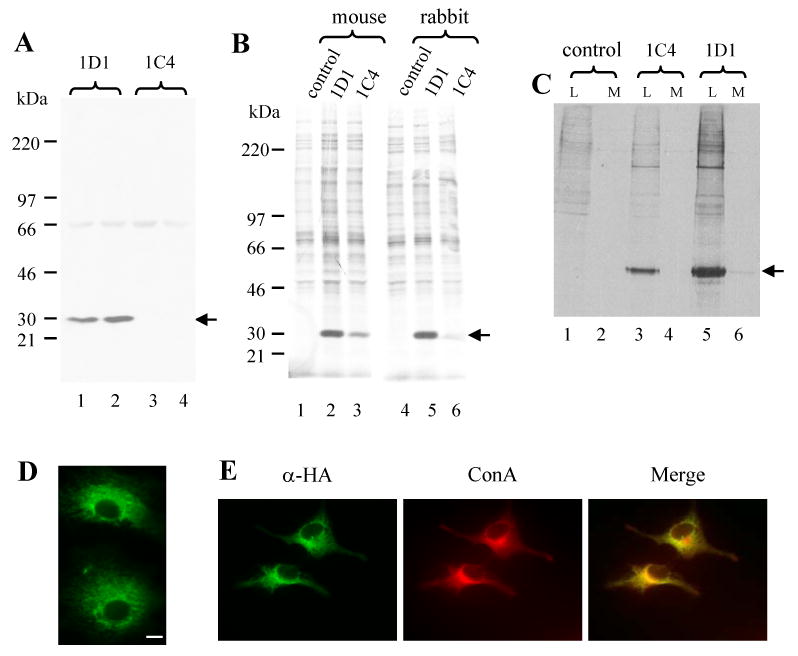

We first tested if our intrabody vectors could be correctly translated by transfection of Cos-7 cells. We transfected the Cos-7 cells with 1D1 and 1C4 sFv vectors. The cell lysate supernatants were used for immunoblot analysis of intrabody expression using anti-HA antibody. We readily detected the intrabody band at the expected size (about 31 kDa) from 1D1 intrabody-transfected cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 2). We failed to detect the expression of intrabody from 1C4 intrabody transfected cells in this experiment (Fig. 1A, lanes 3 and 4). In a separate approach, the cells were labeled with 35S-methionine. The expression of the intrabody was determined by immunoprecipitation with mouse or rabbit anti-HA antibodies. A 31 kDa band could be detected by either mouse monoclonal or rabbit polyclonal antibody against HA in the Cos-7 cells transfected with 1D1 intrabody (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 5). A weak band was also detected in the cells transfected with 1C4 intrabody (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 6), but not in the cells transfected with the empty vector (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 4). This same observation was seen in differences in immunofluorescent staining of cells transfected with 1D1 and 1C4 intrabody constructs (data not shown). Immunoprecipitation of cell lysates and culture medium (Fig. 1C, L for cell lysate; M for culture medium) with anti-HA antibody revealed strong intracellular expression, and minimal secretion. Immunofluorescence staining of the Cos-7 cells transfected with 1D1 intrabody showed a reticular pattern of distribution of the intrabody (Fig. 1D). Double staining of the cells with anti-HA and anti-Concanavalin A, showed successful targeting of the 1D1 intrabody to the ER (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these results demonstrated the 1D1 intrabody is efficiently targeted to, and retained within, the ER.

Fig. 1. Expression of the intrabody in Cos-7 cells.

The cell lysate supernatants were prepared from the 1D1 and 1C4 intrabody-transfected Cos-7 cells and separated on 4-12% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (A). The cell lysate supernanants were prepared from the 1D1, 1C4- intrabody-transfected and empty vector- (control) transfected Cos-7 cells that were labeled in the presence of 35S-methionine for 4 hours. The intrabody proteins in the samples were immunoprecipitated with either mouse monoclonal or rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibodies and separated on 4-12% SDS-PAGE (B). The cell lysate supernatant and culture medium were prepared from the 1D1, 1C4 intrabody-transfected and empty vector (control) transfected Cos-7 cells that were labeled in the presence of 35S-methionine for 4 hours. The intrabody proteins in the cell lysates (L) and in the culture medium (M) were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies and separated on 4-12% SDS-PAGE (C). The Cos-7 cells were cultured on cover slips and transfected with 1D1, 1C4 intrabody or empty vector. The cells were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody followed with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibodies. The 1D1 intrabody-transfected cells are shown (D). No detectable signal was found in the control and 1C4 transfected cells (not shown). In a separate experiment, the Cos-7 were cultured on cover slip and transfected with 1D1 intrabody. The cells were incubated with anti-HA antibody followed with FITC conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibodies and with Texas Red conjugated ConA. Arrows in (A), (B) and (C) indicates the intrabody. Bars in (D) and (E) are 10 μm.

1D1 intrabody blocks apoB secretion

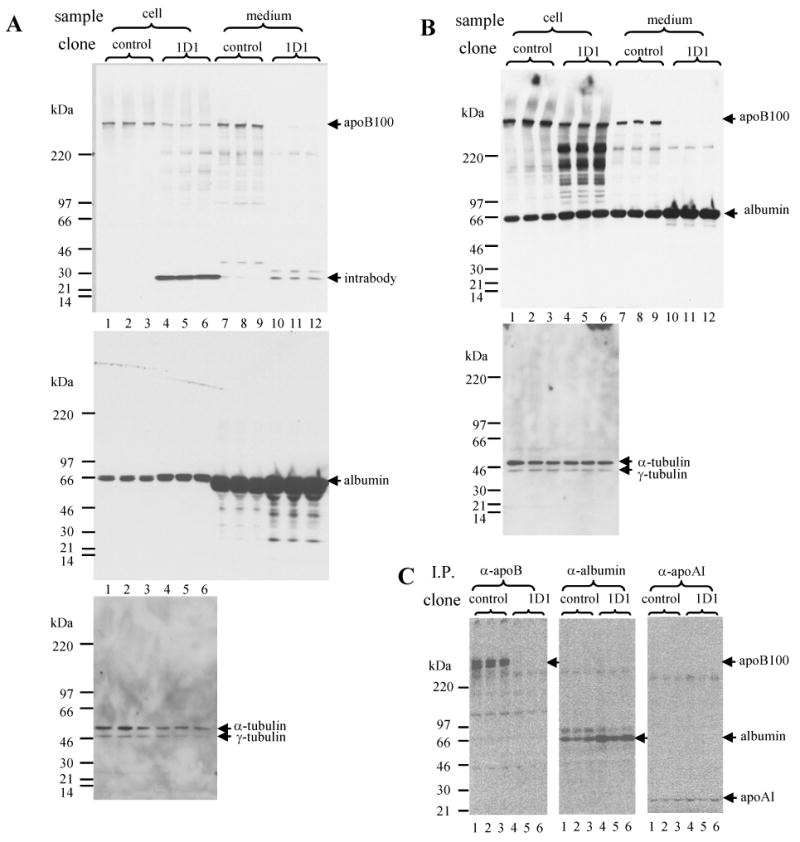

We then made 1D1 intrabody stable transfectants of HepG2 cell to test the hypothesis that the intrabody expression reduces apoB secretion. We obtained several stable individual clones that were transfected with the 1D1 intrabody vector, of which two had good expression of the intrabody protein. In the case of clone1D1-3 intrabody protein could be easily detected in the cell lysate supernatant (Fig. 2A, upper panel, lanes 4-6), but not in that of the control cells (Fig. 2A, upper panel, lanes 1-3). Compared to the control cells, the 1D1-3 cells secreted little apoB100 into culture medium (Fig. 2A, upper panel, compare lanes10-12 vs lanes 7-9). The albumin in the cells (Fig. 2A, middle panel, compare lanes 4-6 vs lanes 1-3) and culture medium (Fig. 2A, middle panel, compare lanes 10-12 vs lanes 7-9) was slightly more in the 1D1-3 cells than that in the control cells. The cellular structural proteins α-tubulin and γ-tubulin in the cells were comparable between the 1D1-3 and control cells (Fig. 2A, lower panel, lanes 4-6 vs. lanes 1-3).

Fig. 2. ApoB intrabody expression reduces apoB secretion in HepG2cells.

Stably transfected cells (control and 1D1-3) were cultured in 10% FBS-containing medium till about 70% confluence. The medium was changed to the same culture medium containing 10% FBS for 48 h incubation (A) or to the culture medium without serum for 8 h incubation (B). After the incubation, the culture medium was collected. The cells were lysed and the lysate supernatant was prepared. Aliquots of medium and cell lysate supernatant were denatured and separated on 4-12% SDS-PAGE for immunoblot analysis with antibodies as indicated. In another experiment, stable transfected cells (control and 1D1-3) were cultured in 10% FBS containing medium till about 70% confluence. The medium was changed to methionine-free medium for 0.5 h preincubation. Then 35S-methionine was added for further 4 h incubation. After the incubation, the culture medium was collected. ApoB, apoAI and albumin in the medium were then immunoprecipitated and separated on 4-20% SDS-PAGE (C).

We believed that FCS in the culture interfered with immunoblot analysis of albumin as evident by presence of a rather wide albumin band in the culture medium (Fig. 2A, middle panel, lanes 7-12) (We tested the antibody and the antibody barely interacted with bovine albumin. However, there appeared much more bovine albumin that was present in the culture medium compared to secreted human albumin from HepG2 cells). We, therefore, repeated the experiment by incubation of the cells in the serum-free medium. Almost identical findings were observed: the 1D1-3 cells secreted little apoB100 into culture medium (Fig. 2B, upper panel lanes, 10-12 vs. lanes 7-9); the albumin in the cells (Fig. 2B, upper panel lanes, lanes 4-6 vs. lanes 1-3) and culture medium (Fig. 2B, upper panel lanes, lanes 10-12 vs. lanes 7-9) was slightly more in the 1D1-3 cells than that in the control cells; the cellular structure proteins α-tubulin and γ-tubulin were comparable between the 1D1-3 and control cells (Fig. 2B, lower panel lanes, lanes 4-6 vs. lanes 1-3).

Immunoprecipitation of apoB from culture medium recovered from cells that had been incubated for 4 h in the presence of 35S-methionine showed similar results: the 1D1-3 secreted little apoB100 (Fig. 2C, left panel, compare lanes 4-6 vs lanes 1-3) but slightly more albumin (Fig. 2C, middle panel, lanes 4-6 vs. lanes 1-3); apoAI secretion appeared to be comparable between the control and 1D1-3 cells (Fig. 2C, right panel, lanes 4-6 vs. lanes 1-3).

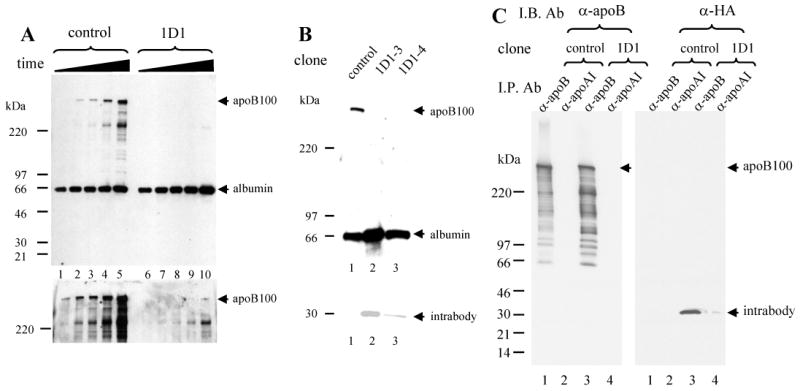

A time course experiment (Fig. 3A) showed that the rate of albumin secretion in the 1D1 cells (lanes 6-10) was mildly increased compared to that in control cells (lanes 1-5). In contrast, whilst there was an easily detectable accumulation of apoB100 (lanes 1-5) in the medium of control cells, apoB100 was essentially undetectable in the medium during the 22-hour culture of the 1D1-3 cells (Fig. 3A, top panel, lanes 6-10). Prolonged exposure of the film revealed only trace amounts of apoB100 secreted by1D1-3 cells for 22 hour culture period that was even lower than that in the medium bathing the control cells for 1 hour (Fig 4A, lower panel, lane 10 vs. lane 1).

Fig. 3. Time course of secretion of apoB and albumin in the control and 1D1-3 cells and comparison of 1D1-3 and 1D1-4.

Stably transfected cells (control and 1D1-3) were cultured in 10% FBS containing medium till about 70% confluence. The medium was changed to the culture medium without serum for incubation of 1 h (lanes 1 and 6), 3.5 h (lanes 2 and 7), 6 h (lanes 3 and 8), 11 h (lanes 4 and 9) and 22 h (lanes 5 and 10) (A). After the incubation, the medium was collected, denatured and separated on 4-12% SDS-PAGE for immunoblot analysis with antibodies against apoB and albumin. Upper panel, short exposure. Lower panel, long exposure.

Stably transfected cells (control, 1D1-3, 1D1-4) were cultured in the medium without serum for 8 h incubation. After the incubation, the culture medium was collected. The cells were lysed and the lysate supernatant was prepared. Medium (upper) and cell lysate supernatant (lower) were denatured and separated on 4-12% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the antibodies indicated (B).

Stably transfected cells (control and 1D1-3) were cultured in 10% FBS containing medium till about 70% confluence. The cells were lysed and the lysate supernatant was prepared for immunoprecipitation with antibodies against either goat anti-apoB or goat anti-apoAI antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were denatured and separated on 4-20% SDS-PAGE for immunoblot analysis with either antibodies against apoB or antibodies against HA (C).

We examined another 1D1 intrabody stably-transfected HepG2 cell clone (1D1-4) and compared its expression with the first clone (1D1-3). Expression of intrabody in the 1D1-4 cells was about one-half that of 1D1-3 cells (Fig. 3B, lower panel, lane 3 vs. lane 2). 1D1-4 cells also displayed reduced apoB secretion that was comparable to that in 1D1-3 cells (Fig. 3B, upper panel, lane 3 vs. lanes 1 and 2). Albumin accumulation in the medium in 1D1-4 cells was slightly lower than that in 1D1-3, however, the level was at least as high as that in controls (Fig. 3B).

Finally, we demonstrated that intrabody protein was readily co-immunoprecipitated with goat anti-apoB antibody from the 1D1 cell lysate supernatant (Fig. 3C, right panel lane 3), but little, if anything was brought down with goat anti-apoAI antibody (Fig. 3C, right panel lane 4), indicating that 1D1 intrabody specifically binds to apoB in 1D1 cells.

In summary, in this investigation we successfully cloned and constructed two intracellular antibodies to human apoB derived from the 1D1 and 1C4 hybridoma cell lines for targeting expression in the ER. We further demonstrated that expression of the 1D1 intrabody in the apoB-secreting human hepatoma cell line HepG2 specifically bound to apoB, thereby almost completely abrogating its secretion from these cells. The knockdown efficiency by intrabody against apoB appears comparable to other strategies to down-regulate apoB by ribozymes, siRNAs and antisense oligonucleotides targeting apoB mRNA [2-5]. Our data indicate the promise of intrabody technology as a potential targeted therapy for the treatment of apoB100-associated hyperlipoproteinemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US NIH Grant HL-51586 and by the T.T. and W.F. Chao Foundation (to L.C.). L.C. was supported by the Betty Rutherford Chair from St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine.

The abbreviations used

- apo

apolipoprotein

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ALLN

N-acetyl-L-leucinyl-L-leucinyl-L-norleucinal

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- sFvs

single-chain antibodies

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jamil H, Gordon DA, Eustice DC, Brooks CM, Dickson JK, Jr, Chen Y, Ricci B, Chu CH, Harrity TW, Ciosek CP, Jr, Biller SA, Gregg RE, Wetterau JR. An inhibitor of the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibits apoB secretion from HepG2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11991–11995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enjoji M, Wang F, Nakamuta M, Chan L, Teng BB. Hammerhead ribozyme as a therapeutic agent for hyperlipidemia: production of truncated apolipoprotein B and hypolipidemic effects in a dyslipidemia murine model. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:2415–2430. doi: 10.1089/104303400750038516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soutschek J, Akinc A, Bramlage B, Charisse K, Constien R, Donoghue M, Elbashir S, Geick A, Hadwiger P, Harborth J, John M, Kesavan V, Lavine G, Pandey RK, Racie T, Rajeev KG, Rohl I, Toudjarska I, Wang G, Wuschko S, Bumcrot D, Koteliansky V, Limmer S, Manoharan M, Vornlocher HP. Therapeutic silencing of an endogenous gene by systemic administration of modified siRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature03121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao W, Ning G. Knockdown of apolipoprotein B, an atherogenic apolipoprotein, in HepG2 cells by lentivirus-mediated siRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:478–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kastelein JJ, Wedel MK, Baker BF, Su J, Bradley JD, Yu RZ, Chuang E, Graham MJ, Crooke RM. Potent reduction of apolipoprotein B and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by short-term administration of an antisense inhibitor of apolipoprotein B. Circulation. 2006;114:1729–1735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.606442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marasco WA, Haseltine WA, Chen SY. Design, intracellular expression, and activity of a human anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 single-chain antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7889–7893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SY, Bagley J, Marasco WA. Intracellular antibodies as a new class of therapeutic molecules for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:595–601. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.5-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rondon IJ, Marasco WA. Intracellular antibodies (intrabodies) for gene therapy of infectious diseases. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pease RJ, Milne RW, Jessup WK, Law A, Provost P, Fruchart JC, Dean RT, Marcel YL, Scott J. Use of bacterial expression cloning to localize the epitopes for a series of monoclonal antibodies against apolipoprotein B100. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:553–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Pease R, Bertinato J, Milne RW. Well-defined regions of apolipoprotein B-100 undergo conformational change during its intravascular metabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1301–1308. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orlandi R, Gussow DH, Jones PT, Winter G. Cloning immunoglobulin variable domains for expression by the polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3833–3837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao W, Yeung SC, Chan L. Proteasome-mediated degradation of apolipoprotein B targets both nascent peptides cotranslationally before translocation and full-length apolipoprotein B after translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27225–27230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao W, Chang BH, Mancini M, Chan L. Ubiquitin-dependent and -independent proteasomal degradation of apoB associated with endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, respectively, in HepG2 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:1019–1029. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.E. Kabat, T. Wu, H. Perry, K. Gottesmann, and C. Foeller, in, 1991 pp. No. 91-3242, 3245th ed United States Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.