Abstract

Since their initial availability in 1997, the thiazolidinediones (TZDs) have become one of the most commonly prescribed classes of medications for type 2 diabetes. In addition to glucose control, the TZDs have a number of pleiotropic effects on myriad traditional and non-traditional risk factors for diabetes. TZDs may benefit cardiovascular parameters, such as lipids, blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, endothelial function and fibrinolytic state. In this review, we summarise the experimental, preclinical and clinical data regarding the effects of the TZDs in conditions for which they are indicated and discuss their potential in the treatment of other conditions.

Keywords: PPARγ, thiazolidinediones, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, troglitazone

Introduction

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) agonists for peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor (PPAR) γ are currently used therapeutically. Troglitazone, the first agent of this class to be approved, was effective in controlling glycemia but was removed from the market because of serious liver toxicity. Pioglitazone and Rosiglitazone are PPARγ agonists currently licensed for the management of hyperglycemia in Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). TZDs induced glycemic improvement is accompanied by a significant reduction in fasting insulin. The magnitude of the improvement depends on many factors such as body mass index (BMI), basal glucose levels, the degree of insulin resistance and the extent of β-cell failure. Interestingly, TZDs may benefit cardiovascular parameters, such as lipids, blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, endothelial function and fibrinolytic state (Parulkar et al 2001; Haffner et al 2002). Moreover, they have been successfully used in non-diabetic insulin resistant conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (Romualdi et al 2003; Glintborg et al 2005).

The purpose of this review is to give a timely examination of the efficacy of PPARγ agonists in conditions for which they are currently indicated and discuss their potential in the treatment of other conditions.

Mechanism of action and insulin resistance

The mechanism of action of thiazolidinediones involves their binding to the nuclear PPARγ receptor. PPARγ is a nuclear receptor that acts as a transcription factor upon activation, by regulating the transcription and expression of specific genes. Together with the isoforms PPAR-α and PPAR-δ, is a member of a family of nuclear hormone receptors that includes the retinoid X receptor (RXR), the vitamin D receptor and the thyroid hormone receptor. PPARs play a critical role as lipid sensors and regulators of lipid metabolism.

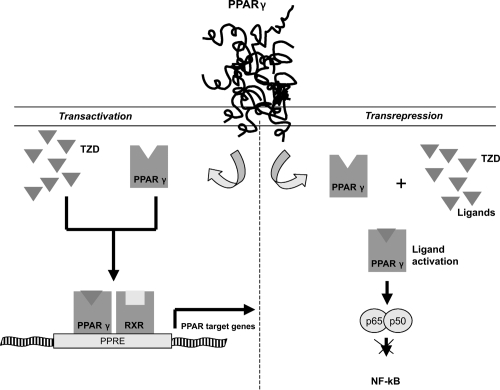

PPARs seem to regulate gene transcription by two mechanisms (Figure 1). Transactivation, a DNA-dependent mechanism that involves binding to PPAR response elements of target genes (see below) and a second mechanism, transrepression, that would explain the anti-inflammatory actions of PPARs. It involves interfering with other transcription-factor pathways in a DNA-independent way (Jarvinen 2004).

Figure 1.

Molecular mechanisms of Thiazolidinediones. In transactivations, perozisome-proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is a nuclear receptor that acts as a transcription factor upon activation. Thiazolidinediones can active PPARγ. On ligand binding, the PPAR forms a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) and they bind to specific peroxisome proliferators response elements (PPRE) on a number of key target genes involved in the carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. In transespression PPARs can repress gene trascription of other pathways, such as nuclear factor −kB (NF-kB).

PPAR-α is principally expressed in tissues that exhibit a high rate of fatty acid metabolism (eg, brown adipose tissue, liver, kidney and heart) and is the molecular target for the fibrate class of drugs (Willson et al 2000). Less is known about the physiological roles of PPAR-δ, which is expressed more ubiquitously, although recent studies have implicated it in lipid trafficking in macrophages and trophoblast (Oliver et al 2001; Chawla et al 2003), blastocyst implantation (Lim and Dey 2000), wound healing (Tan et al 2001), and the regulation of fatty acid catabolism and energy homeostasis (Peters et al 2000; Wang et al 2003). PPAR-γ is mainly found in adipose tissue, intestinal cells and macrophages, although it is also expressed in other tissues including skeletal muscle and endothelium at lower concentrations (Perry and Petrie 2002).

On ligand binding, the PPAR forms a heterodimer with the RXR and they bind to specific peroxisome proliferators response elements (PPRE) on a number of key target genes involved in the carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Endogenous ligands of PPAR-γ include long chain unsaturated fatty acids and prostanoids (Shiraki et al 2005). Insulin resistance is caused by multiple factors, most likely involving many different aspects of the metabolic regulation of insulin in muscle, liver and adipose tissue.

Current evidence supports the notion that the primary target tissue of TZDs is the adipose tissue. Their effect on insulin-stimulated glucose disposal may in part be secondary to changes in adipose tissue, where PPAR-γ is predominantly expressed, and involve factors that alter peripheral insulin sensitivity. TZDs have been shown to selectively stimulate lipogenic activities in fat cells resulting in greater insulin suppression of lipolysis (Oakes et al 2001). They decrease FFAs available for infiltration into other tissues; thus TZDs treatment target the insulin-desensitizing effects of FFAs in muscle and liver (Vasudevan and Balasubramanyam 2004). Finally, TZDs have been shown to alter expression and release of adipokines. Resistin and TNF-α, which have the potential to decrease insulin sensitivity, are reduced following incubation with TZDs (Steppan et al 2001: Hofmann et al 1994; De Vos et al 1996). Conversely, the level of adiponectin is increased after TZD treatment in vitro (Maeda et al 2001). Additionally, TZDs enhance the lipid storage capacity of adipose tissue by increasing the number of small adipocytes. This lipogenic effect may lead to a reduction of deleterious lipid accumulation in other insulin-sensitive tissues such as the muscle and liver, thus reducing insulin resistance (Okuno et al 1998).

The TZDs therefore hold promise as agents that can ameliorate insulin resistance due to lipotoxicity in obesity- and lipodystrophy-associated T2DM (Unger and Orci 2001).

Clinical effects

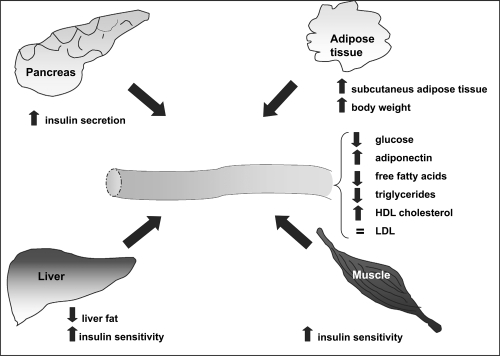

The TZDs have been shown to mediate a variety of effects on the complex pathophysiology associated with insulin resistance (Bhatia and Viswanathan 2006) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical effects of Thiazolidinediones.

They are now approved for the treatment of T2DM and offer a new angle of attach in the pharmacologic management of T2DM.

Unlike other oral antidiabetic agents, TZDs are unique because they improve insulin sensitivity by increasing insulin-mediated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, suppressing hepatic glucose output and improving the secretory response of insulin in pancreatic β-cells (Camp 2003).

The TZDs are indicated in the United States for monotherapy and as combination therapy with sulfonylureas, metformin and insulin for treatment of T2DM (Diamant and Heine 2003).

Rosiglitazone and pioglitazone are the only TZDs available for clinical uses.

As monotherapies, both agents significantly improve insulin sensitivity and glycemic control in T2DM patients by decreasing plasma glucose and plasma insulin levels, thus reducing HbA1c levels from 0.5% to 1.9% (Lebovitz et al 2001; Miyazaki et al 2001). In combination therapy with other oral diabetes medications, both rosiglitazone and pioglitazone demonstrate additive effects on glycemic control compared with monotherapy (Camp 2003).

Effect of adipocytes and serum lipid profile

The typical lipid profile of T2DM is characterized by low HDL, hypertriglyceridemia, and degeneration of atherogenic, small, dense LDL-cholesterol particles which are prone to oxidation and glication (Ginsberg et al 2005). Pioglitazone have beneficial effects in attenuating this complex dyslipidemic states. Typical beneficial effects in attenuating this complex dyslipidemic state have been described in studies using pioglitazone (Einhorn et al 2000; Rosenstck et al 2002) and rosiglitazone (Patel et al 1999; Raskin et al 2000; Fhillips et al 2001). Data for rosiglitazone, in combination with metformin for 26 weeks showed an HDL increase of 13.3%, LDL increase of 18.6% and a neutral effect on total cholesterol (Fonseca et al 2000). A study reported by Khan et al found that pioglitazone was superior to rosiglitazone in terms of lowering triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC) in T2DM patients (Khan et al 2002). By modulating adipogenic differentiation, the in vivo effects of TZDs on lipid profile may be do to the repartitioning of lipids. Studies in human tissue point to a critical role for PPARγ in the regulation of adipogenesis. Exposure of human pre-adipocytes to TZDs induces differentiation (Adams et al 1997). Intriguingly, pre-adipocytes isolated from subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue have been shown to differentiate more readily in response to TZDs than from visceral depots taken from the same subjects (Adams et al 1997).

Evidence emerging from studies of humans and mice has indicated PPARγ to be not only a key factor for adipogenesis but also a critical determinant of body fat distribution (Tsai and Maeda 2005). In patients with T2DM studied by computerized tomography, visceral adipose tissue decreased following TZDs treatment while subcutaneous adipose tissue increased (Mori et al 1999).

These findings correlate with the adipogenic effects of TZDs used in clinical practice; treated type 2 diabetic patients accumulate subcutaneous fat, whereas visceral adipose tissue volume is reduced or unchanged (Bays et al 2004). It is well-established that subcutaneous adipose tissue is metabolically less harmful than visceral adipose tissue (Montague et al 2000). This may, in part, explain the beneficial effects of TZDs despite their tendency to induce weight gain (Bays et al 2004).

Effect on inflammation and atherosclerosis

Atherogenesis is believed to be initiated by passage of lipid through the vascular endothelium, and deposition in the arterial intima, where it stimulates an inflammatory response. The anti-inflammatory properties of TZDs, in addition to their metabolic effects, may confer further cardiovascular benefits (Blaschke et al 2006).

PPARγ agonists have been shown to reduce endothelial expression of VCAM-1 (Pasceri et al 2001) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (Wang et al 2002) on activated endothelium. Thus TZDs, through modulating inflammation, may influence the early stages of atherosclerosis.

The subsequent immune response, monocyte chemotaxis, T-cell activation and vascular smooth cell migration, forms the atherosclerotic plaque. It was recently demonstrated that pioglitazone and rosiglitazone have direct anti-inflammatory effects in a rat model of atherosclerosis via interference with monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 and its monocyte receptor (CCR2) (Ishibashi et al 2002; Han et al 2000).

As monocytes enter in the intima they undergo transformation into macrophages. They take up lipid deposited in the intima forming the “foam cells”. Foam cells may play a pivotal role in atherogenesis, secreting reactive oxygen species and inflammatory cytokines. PPARγ is upregulated in activated macrophages while PPARγ agonists have been shown to attenuate the inflammatory response in activated monocytes and macrophages. Thus, activation of PPARγ receptors in macrophages within the arterial intima may reduce cytokine production, limiting the local inflammatory response, hence arresting atherosclerosis (see below) (Roberts et al 2003).

Effect on endothelial dysfunction and blood pressure

The TZDs have salutary effects on endothelial dysfunction, a key factor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (Widlansky et al 2003). Endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) is responsible for vasodilatation, and No- synthase (eNOS) expression, is diminished in diabetic patients. It has been shown that TZDs up-regulates eNOS expression (Goya et al 2006). Expression of endothelin-1 (ET-1), a potent endothelial-derived vasoconstrictor compound, thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of numerous complications of diabetes, is regulated by TZDs action (Hopfner and Gopalakrishnan 1999). In a randomized study rosiglitazone was shown to improve endothelial dysfunction (Natali et al 2002).

TZDs are also able to exert direct beneficial vascular effects beyond their effect on glycemia, thus reducing cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetics. For example, rosiglitazone has been reported to increase differentiation towards the endothelial lineage when treating a heterogeneous population of angiogenic precursors, an effect mediated by PPAR-γ (Wang et al 2004)

Twelve-week treatment with rosiglitazone improved endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) number and migratory activity of T2DM patients (Pistrosch et al 2005).

Also pioglitazone was demonstrated to have a PPAR-γ dependent stimulation effect on EPCs (Redondo et al 2007).

Some observations strongly suggest that insulin resistance per se is related to endothelial dysfunction, independent of glycemic control, and that rosiglitazone has therapeutic effects on this endothelial dysfunction (Pistrosch et al 2004). Interestingly, these endothelium-related effects are observed even in non-diabetic subjects (Horio et al 2005).

Studies conducted on mammalian models of diabetes suggest that TZDs may be useful in the treatment of hypertension, particularly when associated with insulin resistance (Grinsell et al 2000; Diep et al 2002; Schiffrin et al 2003). Bakris et al demonstrated significant reduction in systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure after 52 week of rosiglitazone treatment (Bakris et al 2000). In another study, decreases in mean arterial blood pressure with the use of troglitazone correlated significantly with reductions in plasma insulin, suggesting a link between improvement of insulin sensitivity and blood pressure reduction (Ogihara et al 1995). ET-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor, as well as a mediator of smooth muscle mitogenesis, and thus a determinant of systemic blood pressure (Miller et al 1993). TZDs treatment has been shown to attenuate the release of ET-1 from vascular cells, which may contribute to the observed blood pressure lowering effect (Satoh et al 1999; Iglarz M et al 2003).

Use in diabetes prevention

Insulin resistance is the key mechanism underlying impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) (Turner and Clapham 1998). Three large-scale intervention trials have demonstrated the beneficial effect of weight reduction, dietary modifications and regular exercise on IGT (Pan et al 1997; Knowler et al 2002; Tuomilehto et al 2001). The overall risk that patients with IGT will develop diabetes is 3–9% per year in the United States (Ipp 2000). TZDs improve insulin sensitivity in a range of insulin-resistant states without diabetes, including obesity and IGT (Ghanim et al 2001; Sekino et al 2003; Bennett et al 2004).

Durbin et al studied 172 IGT patients and demonstrated that the incidence of diabetes after three years was 88.9% lower in the TZD’s treated group compared with the control group (Durbin 2004).

The pivotal problem of progression to overt diabetes from a prediabetic state is impaired β-cell function to begin with decline due to glucolipotoxicity; β-cell is unable to meet the insulin requirements imposed by insulin resistance The TRIPOD Study (Troglitazone in the Prevention of Diabetes Mellitus) (Buchanan et al 2002)was a double blind prospective, randomized, placebo controlled, study examining Hispanic women without diabetes but with previous gestational diabetes. In this study troglitazone had a sustained beneficial effect on β-cell function in addition to the insulin-sensitizing and glucose lowering properties still present 8 months after discontinuation of the medication. The administration of troglitazone reduced the incidence of diabetes by 50% in high-risk women. All these data strongly advocate a role of this class of drugs in the prevention of T2DM.

Safety

The TZDs are generally safe and well tolerated. The liver toxicity that resulted in withdrawal of troglitazone from market does not seem to be a problem with rosiglitazone and pioglitazone (Scheen 2001). The incidence of liver toxicity occurred in approximately one in 100000 patients (Tolman 2000; Parulkar et al 2001). There is no clear molecular explanation for this adverse effect, however, it was reported that troglitazone, unique among the TZDs, activates the pregnane X receptor, a transcription factor that induces the expression of the hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4 gene (Kliewer et al 1999; Lehmann et al 1998). Following the withdrawal of troglitazone, the liver enzyme levels of patients prescribed rosiglitazone or pioglitazone have been carefully monitored, and no increase in TZD-induced liver toxicity has been reported.

The TZDs have been associated with weight gain of 3–5 Kg in a dose-dependent manner, most likely due to an increase in fat mass, peripheral edema or both. In particular the weight gain noted with TZD therapy may actually be associated with a beneficial redistribution of fat between the visceral versus subcutaneous body compartments (Nakamura et al 2001; Nesto et al 2003). Visceral adipose tissue is associated with the metabolic syndrome, being morphologically and functionally different from subcutaneous adipose tissue. Insulin effects trend to be blunted, and glucocorticoid and catecholamine effects trend to be enhanced in visceral adipose tissue compared with subcutaneous adipose tissue.

Fluid retention, expanded plasma volume and dependent edema have been noted with TZD therapy (Nesto et al 2003). In most of these cases, patients showed peripheral edema (swelling of legs, ankles, hands and face). In clinical practice, 3–5% of patients on either pioglitazone or rosiglitazone develop peripheral edema (Nesto et al 2003). The incidence of edema is much higher (up to 15%) in combination therapies that include insulin or sulfonylureas (Malinowski and Bolesta 2000). Although the precise mechanism underlying the edema are unclear, some studies have suggested a vascular leak syndrome, possibly due to increased concentrations of vascular permeability factors and enhancement of endothelial-mediated vasodilation (Emoto et al 2001; Niemeyer and Janney 2002). Exacerbation of congestive heart failure (CHF) has rarely been reported with the use of TZDs (Nesto et al 2003). Because patients with advanced heart failure were not evaluated in clinical studies, TZDs are currently not recommended for use in individuals with New York Heart Association Class III or IV heart failure symptoms.

In their meta-analysis, Nissen and Wolski (2007) still suggest that rosiglitazone is associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction. The main limitations of this study are the quality and quantity of the available data (Psaty and Furberg 2007). The mechanism for the apparent increase death from cardiovascular causes associated with rosiglitazone remains uncertain. One potential contributing factor may be a modest reduction in the hemoglobin level. In susceptible patients, a reducted hemoglobin level may result in increased physiological stress, thereby provoking myocardial ischemia. These data point to the urgent need for comprehensive evaluations to clarify the cardiovascular risk of TZDs.

Future applications of PPAR agonists

TZD therapy appears to result in a variety of effects independent of blood glucose lowering which may have the potential to revolutionize the management of T2DM (Boden and Zhang 2006). Evidently, TZDs improve insulin sensitivity not only of T2DM but also of primarily non-diabetic conditions. Theoretically, this opens the possibility of pharmacological prevention of T2DM and associated disease as strongly suggested by the sustained beneficial effect in women with previous gestational diabetes (Stumvoll 2003).

The anti-inflammatory properties of the TZDs are particularly interesting in the context of atherosclerosis, now recognised to have a central inflammatory component. Their immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects may have a powerful impact on the cardiovascular disease burden associated with T2DM. There are some very recent results from the Prospective Pioglitazone Clinical Trial In Macrovascular Events (PROactive study). They show that pioglitazone reduces the occurrence of fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (Erdmann et al 2007)and recurrent stroke (Wilcox et al 2007) in high-risk patients with T2DM. On the other hand, metabolic control as a surrogate endpoint did not demonstrate clinically relevant differences to the other oral antidiabetic drugs and the occurrence of edema was significantly raised. Therefore, until new evidence becomes available, the benefit-risk ratio of pioglitazone remains unclear (Richter et al 2006).

In ADOPT study is compared rosiglitazone with metformin and glyburide in terms of the duration of glycemic control. Recent data show a cumulative incidence of monotherapy failure at 5 years of 15% with rosiglitazone, 21% with metformin and 34% with glyburide (Kahn et al 2006).

The DREAM trial and related studies are determining if rapamil or rosiglitazone reduces the number of cases of diabetes and atherosclerosis, and are trying to identify novel risk factors for diabetes (DREAM Study 2004).

These and other large randomized studies are under way to evaluate this theme including, RECORD (Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiac outcomes and regulation of glycemia in diabetes), ACCORD (Action to control cardiovascular risk in diabetes), PPAR (PPARg agonists for the prevention of late adverse events following percutaneous revascularisation).

Final results of these studies will shed light on effects of TZDs in treatment and prevention of insulin resistance, IGT and T2DM.

Abbreviations

- T1DM

type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes

References

- Adams M, Montague CT, Prins JB, et al. Activators of PPAR-gamma have depot-specific effects on human preadipocyte diffentiation. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3149–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI119870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakris FL, Dole JF, Porter LE, et al. Rosiglitazone improves blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2000;49:A96. [Google Scholar]

- Bays H, Mandarino L, DeFronzo RA. Role of the adipocyte, free fatty acids, and ectopic fat in pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus: peroxisomal proliferators-activated receptor agonists provide a rational therapeutic approach. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:463–78. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SM, Agrawal A, Elasha H, et al. Rosiglitazone improves insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance and ambulatory blood pressure in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabet Med. 2004;21:415–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V, Viswanathan P. Insulin resistance and PPAR insulin sensitizers. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;7:891–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke F, Caglayan E, Hsueh WA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists: their role as vasoprotective agents in diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006;35:561–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden G, Zhang M. Recent findings concerning thiazolidinediones in the treatment of diabetes. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2006;15:243–50. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Peters RK, et al. Preservation of pancreatic beta-cell function and prevention of Type 2 diabetes by pharmacological treatment of insulin resistance in high risk hispanic women. Diabetes. 2002;51:2796–803. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp HS. Thiazolidinediones in diabetes: current status and future outlook. Curr Opin in Investig Drugs. 2003;4:406–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla A, Lee CH, Barak Y, et al. PPARdelta is a very low-density lipoprotein sensor in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1268–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337331100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos P, Lefebvre AM, Miller SG, et al. Thiazolidinediones repress ob gene expression in rodents via activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1004–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI118860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamant M, Heine RJ. Thiazolidinediones in type 2 diabetes mellitus: current clinical evidence. Drugs. 2003;63:1373–405. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep QN, El Mabrouk M, Cohn JS, et al. Structure, endothelial function, cell growth, and inflammation in blood vassels of angiotensina II-infused rats: role of peroxisome proliferator-acvtivated receptor-gamma. Circulation. 2002;105:2296–302. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016049.86468.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin RJ. Thiazolidinedione therapy in the prevention/delay of type 2 diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and insulin rsistance. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2004;6:280–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-8902.2004.0348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn D, Rendell M, Rosenzweig J, et al. For the pioglitazone 027 study group: pioglitazone hydrochloride in combination with metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2000;22:1395–409. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(00)83039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto M, Anno T, Sato Y, et al. Troglitazone treatment increases plasma vascular endothelial growth factor in diabetic patients and its mRNA in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 2001;50:1166–70. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann E, Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, et al. The effect of pioglitazone on recurrent myocardial infarction in 2,445 patients with type 2 diabetes and previous myocardial infarction: results from the PROactive (PROactive 05) Study. JAm Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1772–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fhillips LS, Grunberger G, Miller E, et al. for the Rosiglitazone Clinical Trials Study Group. Once- and twice-daily dosing with rosiglitazone improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:308–15. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca V, Rosenstock J, Patwardhan R, et al. Effect of metformin and rosiglitazone combination therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1695–702. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein HC, Yusuf S, Holman R, et al. The DREAM Trial Investigators. Rationale, design and recruitment characteristics of a large, simple international trial of diabetes prevention: the DREAM trial. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1519–27. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanim H, Garg R, Aljada A, et al. Suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB and stimulation of inhibitor kappaB by troglitazone: evidence for an anti-inflammatory effect and a potential antiatherosclerotic effect in the obese. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1306–12. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg HN, Zhang YL, Hernandez-Ono A. Regulation of plasma triglycerides in insulin resistance and diabetes. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:232–40. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glintborg D, Stoving RK, Hagen C, et al. Pioglitazone treatment increases spontaneous growth hormone (GH) secretion and stimulated GH levels in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5605–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goya K, Sumitani S, Otsuki M, et al. The thiazolidinedione drug troglitazone up-regulates nitric oxide synthase expression in vascular endothelial cells. J Diabetes Complications. 2006;20:336–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinsell JW, Lardinois CK, Swislocki A, et al. Pioglitazone attenuates basal and postprandial insulin concentrations and blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. A J Hypertens. 2000;13:370–5. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner SM, Greenbeg AS, Weston WM, et al. Effects of rosiglitazone treatment on non-traditional markers of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2002;106:679–84. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025403.20953.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K-H, Chang MK, Boullier A, et al. Oxidized LDL reduces monocyte CCR2 expression through pathways involving peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:793–802. doi: 10.1172/JCI10052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann C, Lorenz K, Braithwaite SS, et al. Altered gene expression for tumor necrosis factor-alfa and its receptor during drug and dietary modulation of insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 1994;134:264–70. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.1.8275942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horio T, Suzuki M, Takamisawa I, et al. Pioglitazone-induced insulin sensitization improves vascular endothelial function in nondiabetic patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1626–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglarz M, Touyz RM, Amiri F. Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-delta and-gamma activators on vascular remodelling in endothelin-dependent hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:45–51. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000047447.67827.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipp E. Impaired glucose tolerance: the irrepressible alpha-cell? Diabetes Care. 2000;23:569–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi M, Egashira K, Hiasa K, et al. Antiinflammatory and antiarteriosclerotic effects of pioglitazone. Hypertension. 2002;40:687–93. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000036396.64769.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvinen H. Thiazolidinediones. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1106–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, St Peter JV, Xue JL. A prospective, randomized comparison of the metabolic effects of pioglitazone or rosiglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes who were previously treated with troglitazone. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:708–11. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. ADOPT Study Group. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. NEngl J Med. 2006;355:2427–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Lehmann JM, Milburn MV, et al. The PPARs and PXRs: nuclear xenobiotic receptors that define novel hormone signalling pathways. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1999;54:345–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of Type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebovitz HE, Dole JF, Patwardhan R, et al. Rosiglitazone monotherapy is effective in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:280–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, et al. The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1016–123. doi: 10.1172/JCI3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H, Dey SK. PPAR delta functions as a prostacyclin receptor in blastocyst implantation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:137–42. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda N, Takahashi M, Funahashi T, et al. PPAR-gamma ligands increase expression and plasma concentrations of adiponectin, an adipose-derived protein. Diabetes. 2001;50:2094–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.9.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski JM, Bolesta S. Rosiglitazone in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a critical review. Clin Ther. 2000;22:1151–68. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(00)83060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RC, Pelton JT, Huggins JP. Endothelins: from receptors to medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;2:54–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90031-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y, Mahankali A, Matsuda M, et al. Improved glycemic control and enhanced insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic subjects treated with pioglitazone. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:710–19. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague CT, O’Rahilly S. The perils of portiliness: causes and consequences of visceral adiposity. Diabetes. 2000;49:883–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y, Murakawa Y, Okada K, et al. Effect of troglitazone on body fat distribution in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:908–12. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.6.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Funahashi T, Yamashita S, et al. Thiazolidinedione derivative improves fat distribution and multiple risk factors in subjects with visceral fat accumulation-double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2001;54:181–90. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(01)00319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natali A, Baldeweg S, Toschi E. Rosiglitazone directly improves endothelial function in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl 2):P-573–A142. [Google Scholar]

- Nesto RW, Bell D, Bonow RO, Fonseca V, et al. Thiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. Circulation. 2003;108:2941–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103683.99399.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer NV, Janney LM. Thiazolidinedione-induced edema. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:924–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.11.924.33626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2457–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes ND, Thalen PG, Jacinto SM, et al. Thiazolidinediones increase plasma adipose tissue FFA exchange capacity and enhance insulin-mediated control of systemic FFA availability. Diabetes. 2001;50:1158–65. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogihara T, Rakugi H, Ikegami H, et al. Enhancement of insulin sensitivity by troglitazone lowers blood pressure in diabetic hypertensives. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:316–20. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)96214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno A, Tamemoto H, Tobe K, et al. Troglitazone increases the number of small adipocytes without the change of white adipose tissue mass in obese Zucker rats. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1354–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver WR, Jr, Shenk JL, Snaith MR, et al. Selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta agonist promotes reverse cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5306–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091021198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parulkar AA, Pendergrass ML, Granda-Ayala R, et al. Nonhypoglycemic effects of thiazolidinediones. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:307. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, Lee S, Li W, et al. Growth, adipose, brain, and skin alterations resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse peroxisome proliferators activated receptor beta (delta) Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5119–28. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5119-5128.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:537–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parulkar AA, Pendergrass ML, Granda-Ayala R, et al. Nonhypoglycemic effects of thiazolidinediones. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:61–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasceri V, Wu H, Willersen J, Yeh E. Modular of vascular inflammation in vitro and in vivo by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor- activators. Circulation. 2001;101:235–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel J, Anderson RJ, Rappaport EB. Rosiglitazone monotherapy improves glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a twelve-week, randomized, placebo controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 1999;1:165–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.1999.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CG, Petrie JR. Insulin-sensitising agents:beyond thiazolidinediones. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2002;7:165–74. doi: 10.1517/14728214.7.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistrosch F, Passauer J, Fischer S, et al. In type 2 diabetes, rosiglitazone therapy for insulin resistance ameliorates endothelial dysfunction independent of glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:484–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistrosch F, Herbring K, Oelschlaegel U, et al. PPARgamma-agonist rosiglitazone increases number and migratory activity of cultured endothelial progenitor cells. Atherosclerosis. 2005;183:163–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psaty BM, Furberg CD. The record on rosiglitazone and risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:67–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin P, Rappaport EB, Cole ST, et al. Rosiglitazone short term monotheraphy lowers fasting and postprandial glucosze in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2000;43:278–84. doi: 10.1007/s001250050045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo S, Hristov M, Gumbel D, et al. Biphasic effect of pioglitazone on isolated human endothelial progenitor cells: involvement of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma and transforming growth factor-beta 1. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:979–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter B, Bandeira-Echtler E, Bergerhoff K, et al. Pioglitazone for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;18:CD006060. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006060.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AW, Thomas A, Rees A, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists in atherosclerosis: current evidence and future directions. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14:567–73. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romualdi D, Guido M, Ciampelli M, et al. Selective effects of pioglitazone on insulin androgen abnormalities in normo- and hyperinsulineamic obese patients with polycystic ovary sindrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1210–18. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstck J, Einhorn D, Hershon K, et al. the pioglitazone 014 study group. Efficay and safety of pioglitazone in type 2 diabetes: a randomised, placebo-controlled study in patients receiving stable insulin theraphy. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56:251–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh H, Tsukamoto K, Hashimoto Y. Thiazolidinediones suppress endothelin-1 secretion from bovine vascular endothelial cells: a new possible role of PPAR on vascular endothelial function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;254:757–63. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheen AJ. Thiazolidinediones and liver toxicity. Diabetes Metab. 2001;27:305–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin EL, Amiri F, Benkirane K, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: vascular and cardic effects in hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:664–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000084370.74777.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekino N, Kashiwabara A, Inoue T, et al. Usefulness of troglitazone administration to obese hyperglycaemic patients with near-normoglycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2003;5:145–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2003.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki T, Kamiya N, Shiki S, et al. Alpha, beta-unsaturated ketone is a core moiety of natural ligands for covalent binding to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14145–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001;409:307–12. doi: 10.1038/35053000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumvoll M. Thiazolidinediones- some recent developments. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12:1179–87. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.7.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan NS, Michalin L, Noy N, et al. Critical roles of PPAR beta/delta in keratinocyte response to inflammation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3263–77. doi: 10.1101/gad.207501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman KG. Thiazolidinedione hepatotoxicity: a class effect? Int J Clin Pract. 2000;113(Suppl):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YS, Maeda N. PPAR-gamma: a critical determinant of body fat distribution in humans and mice. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:81–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JC, et al. Prevention of Type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NC, Clapham JC. Insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance and non-insulin dependent diabetes, pathologic mechanisms and treatment: current status and therapeutic possibilities. Prog Drug Res. 1998;51:33–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8845-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger RH, Orci L. Diseases of liporegulation: new perspective on obesity and related disorders. FASEB J. 2001;15:312–21. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan AR, Balasubramanyam A. Thiazolidinediones: a review of their mechanism of insulin sensitiziation, therapeutic potential, clinical efficacy, and tolerability. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2004;6:850–63. doi: 10.1089/dia.2004.6.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Verna L, Chen N-G, et al. Constitutive activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma suppresses pro-inflammatory adhesion molecules in human vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34176–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, Lee CH, Tiep S, et al. Peroxisome-prolifator-activated receptor delta activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell. 2003;113:159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CH, Ciliberti N, Li SH, et al. Rosiglitazone facilitates angiogenic progenitor cell differentiation toward endothelial lineage: a new paradigm in glitazone pleiotropy. Circulation. 2004;109:1392–400. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000123231.49594.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widlansky ME, Gokce N, Keaney JF, Jr, et al. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1149–60. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox R, Bousser MG, Betteridge DJ, et al. Effects of pioglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes with or without previous stroke: results from PROactive (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events 04) Stroke. 2007;38:865–73. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257974.06317.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson TM, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, et al. The PPARs: fro orphan receptors to drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2000;43:527–50. doi: 10.1021/jm990554g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]