Abstract

Background

Initiation and maintenance of compulsive alcohol drinking involves a sequence of behaviors which occur in the presence of environmental cues. Animal models using chained schedules of alcohol reinforcement may be useful for examining the complex interactions between cues and alcohol seeking and consumption.

Methods

Four baboons self-administered alcohol under a 3-component chained schedule of reinforcement; distinct cues were presented in the context of different behavioral contingencies associated with gaining access to 4% w/v alcohol (alcohol seeking) and concluding with alcohol self-administration. First, the response strength of alcohol-related seeking responses was evaluated using a between-sessions progressive ratio (PR) procedure in which the response requirement to initiate the final contingency and gain access to the daily supply of alcohol was increased each session. The highest response requirement completed that resulted in alcohol access was defined as the breaking point (BP). Second, water was substituted for alcohol and PR procedures were repeated. The effects of increasing the “seeking” response requirement on subsequent alcohol or water consumption were also determined.

Results

When alcohol was available, operant responses to gain access to and self-administer alcohol were maintained. When water was substituted for alcohol, alcohol-related cues continued to maintain alcohol-seeking responses. However, higher BPs, higher rates of self-administration and higher volumes of intake occurred when alcohol was available compared to water. Increasing the response requirement to gain access to alcohol did not reduce alcohol consumption (total alcohol intake).

Conclusions

These results show that alcohol-related cues maintained alcohol seeking even after a prolonged period of water only availability. Cue-maintained alcohol seeking behavior can be dissociated from subsequent alcohol consumption.

Keywords: Cue reactivity, craving, self-administration, alcohol, progressive ratio

INTRODUCTION

Compulsive alcohol drinking can be conceptualized as a sequence of responses and behavioral contingencies that occur in the presence of environmental stimuli and terminate in alcohol consumption. All of the behaviors, including those leading up to self-administration, occur in the presence of environmental stimuli that come to play a critical role in the drug abuse syndrome (Markou et al., 1993; Pickering and Liljequist, 2003; Robinson and Berridge, 1993). As a result, understanding the processes that control behavior leading up to self-administration (termed appetitive or “seeking”), and the interaction of those behaviors with environmental stimuli, has become a focus of drug abuse research (Kirby et al., 1997; Rodd et al., 2004; Vanderschuren and Everitt, 2005). Development of procedures in which drug-seeking and drug self-administration can be studied independently is a research priority (Samson and Czachowski, 2003).

To that end, Samson and colleagues (1998) developed a procedure in rats in which the appetitive (seeking) and consummatory (self-administration) phases of alcohol drinking were assessed separately within the same experimental session. In their procedure, rats were trained to press a lever under a fixed-ratio schedule of reinforcement to gain access to a sipper tube connected to alcohol solutions (seeking phase). Once the response requirement was completed, alcohol drinks were freely available for a set duration of time (e.g., 20-minute) (consummatory phase), and rats could obtain an unlimited number of drinks. Studying alcohol-seeking behavior in this model does not involve extinction of alcohol-maintained responding as in reinstatement models, but allows measurement of alcohol-motivated behaviors involved in the maintenance of alcohol drinking (Samson et al., 1998). The motivation to consume alcohol has been evaluated using this model and progressively increasing the response requirement to gain access to alcohol (Czachowski and Samson, 1999). When tested under these conditions, higher response requirements were completed by alcohol-preferring (P) and high-alcohol drinking (HAD) rats when compared to outbred rats (Czachowski and Samson, 2002). Both P and HAD strains consumed similar amounts of alcohol, but P rats emitted more appetitive responses than HAD rats (Czachowski and Samson, 2002).

In another approach, Weerts et al. (2006) reported a baboon drinking procedure consisting of a chained schedule of alcohol reinforcement composed of separate contingencies (“components”), each of which was correlated with a different stimulus (“cue”). Fulfilling the schedule requirement in each successive component was necessary to progress to the next component, with the primary reinforcer (in this case, alcohol) available only in the final component. Like Samson et al.’s (1998) appetitive/consummatory model in rats, the baboon drinking procedure allowed manipulation of conditions leading to alcohol access (seeking) and alcohol self-administration (consumption) separately. Before experimental manipulations, alcohol drinking was established in the baboons. Once alcohol reinforcement was demonstrated, the chained schedule of stimulus events and behavioral contingencies was initiated. A sequence of lights and tones (i.e., cues) was presented during 3 linked components in the daily 3-hour session. Cues were initially neutral, in that the sequence of cues was presented alone and no programmed behavioral contingencies were in effect. Second, the same sequence of cues was presented, but was paired with different behavioral contingencies leading to and concluding with access to alcohol for self-administration in the last component. Weerts et al. (2006) reported that after the cues had been paired with the contingencies of the chained schedule of alcohol reinforcement for 5 weeks, cues presented in the components leading to alcohol access elicited Pavlovian conditioned responses (orient and approach) and occasioned operant responding that facilitated access to alcohol (alcohol-seeking). Increasing the response requirement (the response “cost”) for each alcohol drink decreased both the number of drinks obtained and the volume of alcohol consumed, but did not alter alcohol-seeking behaviors. In contrast, following periods of forced abstinence (1–14 days), behaviors associated with alcohol seeking and self-administration and volume of alcohol consumed were increased on the first day that cues were again presented and alcohol was again available for consumption. Thus, alcohol self-administration and consumption were sensitive to both increases in response “cost” per drink and duration of alcohol abstinence, whereas the seeking behavior was enhanced only by duration of alcohol abstinence.

The current study used a variation of the Weerts et al. (2006) procedure to evaluate the effects of increasing the response “cost” to gain access to alcohol or its vehicle (water); that is, response cost during the “seeking” component of the chained schedule. This variation consisted of adding a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule to the seeking component of the chained schedule. In a PR schedule, the number of responses required for each reinforcer is systematically increased until the animal fails to complete the response requirement within a specified period of time (Hodos, 1961; Hodos and Kalman, 1963). The size of the last ratio requirement completed before this criterion is met is called the “breaking point” (BP). Orderly increasing relations have been reported between BP and variables that increase “motivation,” such as level of food deprivation, concentration or volume of a liquid reinforcer (Hodos, 1961; Hodos and Kalman, 1963), and intensity of electrical brain stimulation (Keesey and Goldstein, 1968). The use of PR procedures, and of BP as an index of the strength (or efficacy) of a reinforcer has been accelerating, particularly in the area of behavioral pharmacology (Stafford et al., 1998), where investigation of variables that reduce or change the efficacy of drugs of abuse is of practical, as well as scientific, interest. One objective of the current study was to compare BPs obtained under conditions leading to access to alcohol versus access to water. In addition, because the response requirement for each individual alcohol drink remained constant throughout the experiment, the relationship between changes in the “seeking” response requirement and subsequent alcohol consumption was also determined.

Subjects were male baboons in which alcohol (4% w/v in water) was self-administered orally and functioned as a reliable reinforcer when compared with vehicle (water). In Weerts et al. (2006), a series of initially neutral environmental stimuli (lights and tones) were presented alone and then during 3 linked components which were designed to model periods of alcohol anticipation (Component 1), alcohol seeking (Component 2), and alcohol consumption (Component 3) within each daily session. As noted above, responding developed in the presence of and was maintained by the stimuli leading to the availability of alcohol (see Weerts et al., 2006). The current study extends our investigation of the relationship between alcohol seeking and consumption which was initiated in the Weerts et al. (2006) study using the same baboons. After stable alcohol drinking was maintained under the chained schedule of alcohol reinforcement, BP determinations were conducted in which the response requirement in Component 2 was progressively increased until the BP was obtained. Next, water was substituted for alcohol and, after volume consumed decreased, BP determinations for water were conducted. Measures of seeking (Component 2), as well as consumption (Component 3), were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Four adult male baboons (Papio anubis, Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, TX), weighing 17 – 30 kg at the beginning of the study, were housed singly in specialized cages that also served as the experimental chambers (as described below). All four baboons had prior histories of cue exposure before and after alcohol self-administration and demonstration of alcohol reinforcement under the chained schedule of reinforcement (Weerts et al., 2006). Cages were positioned to allow full visual, olfactory, and auditory contact with other singly housed baboons in the room. Baboons were fed amounts of standard primate chow (biscuits) adjusted to maintain sufficient caloric intake (e.g., 50–73 kcals/kg) for normal baboons of their size, age, and activity level. They also received daily food supplements [2 pieces of fresh fruit or vegetables (70–120g each) and a children’s chewable multivitamin]. Using these procedures, baboons maintain relatively stable weights but do slowly gain weight (as they age) as typically reported in the literature for adult captive male baboons (Comuzzie et al., 2003; Hainsey et al., 1993; Mahaney et al., 1993). Drinking water was available ad libitum from a spout mounted on the front of the cage, except during the experimental sessions (see below). The housing room was maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 AM and off at 6:00 PM). The facilities were maintained in accordance with USDA and AAALAC standards. The protocol was approved by the JHU Animal Care and Use Committee and followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996).

Apparatus

Each customized baboon cage was equipped with a bench along 1 side of the cage and an aluminum “intelligence panel” mounted on the same side as the bench. Configurations of the cage and intelligence panel have been described in detail previously (Weerts et al., 2006). Briefly, the intelligence panel contained the following: 2 custom-made vertically operated levers with different colored “jewel” lights mounted above each lever, a “drinkometer” (Kandota Instruments, Sauk Center, MN) for delivery of alcohol and vehicle solutions, and a food hopper. The drinkometer contained a faceplate with 4 lights (2 white and 2 green) which surround a protruding drink spout. Contact with the drink spout operated a solenoid valve that delivered fluid for 5 seconds (approximately 25 – 35 mL). A 1000-mL glass bottle that contained alcohol or vehicle solutions was positioned above the cage and connected to the drinkometer with tygon tubing. A speaker was mounted above the cages for presentation of auditory stimuli (e.g., tones). Three different colored (red, yellow, blue) cue lights (3 in. diameter) were mounted on a separate panel on the back wall of the cage; lights were mounted 3 in. apart. Experimental procedures were controlled remotely from another room using Med Associates (East Fairfield, VT) software and hardware interfaced with a personal computer.

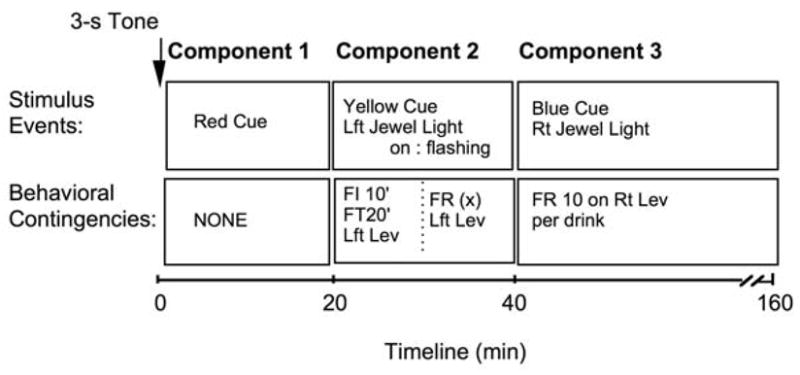

Procedures for Chained Schedule of Alcohol Reinforcement

Immediately before the sessions, the drinking water spout was disabled so that fluids were available only via the drinkometer. The timeline of the experimental session, stimulus events, and behavioral contingencies in effect are depicted in Fig. 1. Sessions began with a 3-second tone followed by illumination of the red cue light (Component 1). No programmed behavioral contingencies were ever in effect during Component 1. The red light was turned off after 20 minutes and the yellow cue light was then constantly illuminated signaling Component 2. Component 2 consisted of 2 links. During the first link, the jewel light over the left lever was illuminated and an alternative fixed interval (FI) 10-min fixed time (FT) 20-min schedule was in effect. According to the schedule, the first link ended (and second link began) either (a) with the first lever press after 10 minutes had elapsed or (b) automatically after 20 minutes if no response occurred within 10 minutes after the 10-minute FI had elapsed. The second link was signaled by a blinking jewel light over the left lever; the yellow cue light also remained illuminated. During the second link, a fixed ratio (FR) X was in effect. During the baseline sessions, X was set to 10 responses and failure to complete the requirement within 10 minutes resulted in termination of the session (i.e., no alcohol access for the day) whereas completion of the response requirement turned off the blinking jewel light and the yellow cue light, ended Component 2, and initiated Component 3. During Component 3, the blue cue light was turned on, the jewel light over the right lever was illuminated, and drinks of alcohol (4% w/v in water) were available for oral self-administration according to an FR 10 schedule of reinforcement on the right lever and contact with the drink spout. Upon completion of each FR, the jewel light was turned off and the two white lights on the drinkometer faceplate were lit to indicate drink availability. A single spout contact resulted in the white lights being turned off and fluid flow through the spout accompanied by illumination of the green lights on the faceplate. Fluid flow for a single spout contact continued for as long as the baboon remained in contact with the spout or for 5 seconds, whichever was shorter. This defined a single drink. The actual duration and volume of each drink (approximately 25 – 35 mL), within the constraints of the maximum duration, were thus under the control of the baboon. Following each drink, all drinkometer lights were turned off and the jewel light over the right lever was again illuminated. Component 3 (i.e., drinkometer access) continued for 120 minutes. At the end of the session, total volume of solution remaining in the bottle connected to the drinkometer was recorded to determine amount consumed.

Fig. 1.

Experimental session timeline of stimulus events and behavioral contingencies in effect under chained schedule of alcohol reinforcement.

Progressive Ratio Procedures

Once self-administration responding for alcohol under the chained schedule procedures was stable (no increasing or decreasing trends), the response strength of alcohol-related seeking responses was evaluated using a between-sessions PR procedure. The FR X requirement in the second link of Component 2 was progressively increased each day by a factor of 2 (i.e., 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, etc.) until the subject failed to complete the response requirement within 90 minutes. Completion of the FR X response requirement immediately initiated Component 3 and alcohol was available as described above. If the FR X response requirement was not completed within 90 minutes, the session terminated after Component 2 (i.e., no alcohol access). The “breaking point” (BP) was defined as the highest response requirement completed in Component 2 that resulted in access to alcohol (i.e., transition to Component 3 where alcohol could be self-administered). Following each determination the baseline schedule was reestablished (FR X = 10). After self-administration had been stable for 3 consecutive days, another BP determination began. At least 3 BPs were determined for each baboon, until there were no increasing or decreasing trends in BP.

Extinction Procedures

Prior to extinction procedures, all alcohol BP determinations were completed and alcohol self-administration was maintained for 2 weeks without interruption. Water was then substituted for 4% w/v alcohol as the fluid available for self-administration in Component 3. The experimental session was the same as described above; that is, all stimuli were presented and all behavioral contingencies of the chained schedule of reinforcement were in effect during the extinction condition. When self-administration and volume of water consumed decreased below the range for alcohol and intake levels had been relatively stable for 5 consecutive days, BPs for water were obtained using the between-sessions progressive ratio procedure described above for alcohol.

Procedures for Determination of Blood Alcohol Level

Three separate blood alcohol level (BAL) determinations were conducted in each baboon. Immediately following an alcohol self-administration session, baboons were anesthetized with ketamine and 5-mL blood samples were collected from a saphenous vein. Samples were immediately centrifuged at 3200 rpm for 8 – 12 minutes and then the plasma drawn off, transferred to two separate airtight polypropylene tubes, and frozen until analysis. Double determinations of BAL were completed using a rapid high performance plasma alcohol analysis using alcohol oxidase with AMI analyzer (Analox Instruments USA, Lenenberg, MA) with Analox Kit GMRD-113 (detects ranges from 0 to 350 mg/dL, using internal standard of 100 mg/dL). Analysis is based on the principle that in the presence of molecular oxygen, ethanol is oxidized by the enzyme alcohol oxidase to acetaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide. Oxygen consumption is directly proportional to ethanol concentration under the controlled conditions of the assay. This assay has been used by other laboratories to determine BALs in rats (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2001) and rhesus monkeys (Katner et al., 2004).

Data Analysis

Chained schedule of reinforcement

The operant data collected via the computer program for all components of the chained schedule were left and right lever presses and number of drinkometer spout contacts. The latency to complete the FI requirement (link 1) in Component 2 and the number of drinks obtained and total volume (mL) of fluid (water or alcohol) consumed in Component 3 were also analyzed. Data were summarized as the grand mean of last 5 days of alcohol self-administration that preceded the extinction condition and the grand means of the first 5 days and the last 5 days of extinction (out of a total of about 30 days of extinction). Data were analyzed using ANOVA, accepting a p-value of 0.05 or less as significant. When significant effects were determined, post-hoc Bonferroni t-tests were conducted.

Progressive Ratio Procedure

The primary dependent variables were left lever presses to complete the FR requirement (link 2) in Component 2 and, if the FR requirement was completed, the number of right lever presses, the number of drinks obtained, and total volume of fluid consumed in Component 3. Since the BP data were not normally distributed, BP values were transformed to number of steps completed (i.e., a BP of 20 = 1 step, a BP of 40 = 2 steps, BP of 80 = 3 steps, etc.); data for water and alcohol were then compared using paired one-tailed t-tests accepting a p-value of 0.05 as significant. A one-tailed test was used as it was predicted that alcohol-maintained behaviors would be higher than those for water. Other data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA accepting a p-value of 0.05 as significant. When significant effects were determined, post-hoc Bonferroni t-tests were conducted.

RESULTS

Chained Schedule of Reinforcement

In the current study, we examined behavior maintained by the alcohol-related cues under conditions of alcohol availability and extinction (water only availability). Operant responses that occurred during Component 2 (alcohol seeking) and Component 3 (self-administration) were compared for conditions in which alcohol-related cues were presented and alcohol and then water were available for consumption under the chained schedule.

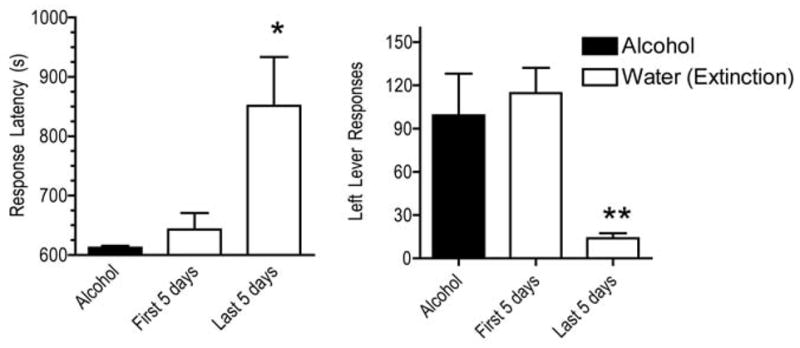

Component 2 (Alcohol Seeking)

As shown in Fig. 2., when alcohol was available, responding was maintained on the left (FI) lever, and the mean (±SEM) latency to complete the FI schedule when alcohol was available was 612.1 (±3.5) seconds (the minimum latency to complete the FI was 600 seconds, i.e., 10 minutes). When water was substituted for alcohol for self-administration in Component 3, alcohol-related cues continued to maintain both left lever responses and a short mean response latency to complete the FI schedule during the first 5 days of substitution. During the last 5 (of approximately 30) days of extinction, the mean latency to complete the FI was increased (Fig. 2, left panel) and the mean number of left lever responses (Fig. 2, right panel) was decreased compared to alcohol. ANOVA confirmed there was a significant difference between the alcohol and extinction conditions for the mean number of left lever responses in Component 2 (F = 7.5, df = 2,13, p< 0.008). Post-hoc Bonferroni t-tests confirmed that the mean number of left lever responses during the first 5 days of extinction was not significantly different from alcohol, while the mean number of left lever responses during the last 5 days of extinction was significantly lower compared to alcohol (t = 3.1, p< 0.05), and the first 5 days of extinction (t = 3.6, p<0.05). ANOVA confirmed there was also a significant difference across conditions for mean latency to complete the FI (F = 5.61, df = 2,13, p<0.02). Post-hoc Bonferroni t-tests isolated this effect as a significant increase in mean latency to complete the FI during the last 5 days of extinction when compared to alcohol (t = 3.1, p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Alcohol seeking operant responses in Component 2 of the chained schedule under conditions of alcohol or water availability in Component 3. Alcohol seeking responses shown are the number of left lever responses (right panel) and the latency to respond (left panel) on the left lever during the FI 10’ FT 20’ schedule in Component 2. Data shown are mean ±SEM for the group for the last 5 days of alcohol availability prior to extinction, and the first 5 days and last 5 days of extinction. * indicates a significant (p<0.05) difference from the alcohol condition and ** indicates significant (p<0.05) differences from both alcohol and the first 5 days of extinction.

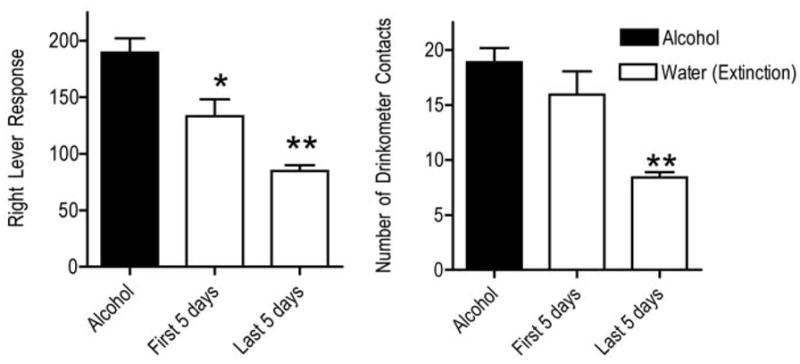

Component 3 (Self-administration)

Alcohol maintained self-administration responses (right lever responses and the number of drink contacts). Typically, at least 80% of total responses and drink contacts occurred in the first 20 minutes of alcohol availability, followed a low number of drinks distributed over the remainder of the 2-hour drinking period (data not shown). This general pattern was not altered by the experimental manipulations. Alcohol-maintained lever responses and drinkometer contacts decreased during extinction (Fig. 3). ANOVA confirmed a significant difference in the mean number of right lever responses for alcohol and water conditions (F = 22.8, df = 2,13, p<0.0001). Post-hoc Bonferroni t-tests showed that the first 5 days of extinction (t = 3.5, p< 0.05) and the last 5 days of extinction (t = 6.76, p<0.001) were both significantly decreased when compared to alcohol. In addition, the last 5 days was significantly lower than the first 5 days of extinction (t = 3.1, p<0.05). Each completion of 10 right lever responses produced an opportunity to drink. Therefore, the number of drink contacts is directly proportional to the number of right lever responses. The right panel of Fig. 3 shows the mean number of drink contacts during the alcohol and extinction conditions. The number of drink contacts decreased during extinction. ANOVA confirmed a significant difference between the mean number of drink contacts during the alcohol and water conditions (F = 16.5, df = 2,13, p<0.0003). Post-hoc Bonferroni t-tests showed that mean number of drink contacts during the first 5 days of extinction did not differ significantly from the alcohol condition. Drink contacts during the last 5 days of extinction were significantly decreased when compared to alcohol (t = 5.5, p< 0.001) and the first 5 days of extinction (t = 3.9, p< 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Self-administration responses in Component 3: the number of right lever responses completed to activate the drinkometer for drinks (left panel) and the number of drinkometer contacts (right panel). Other details as in Fig. 2.

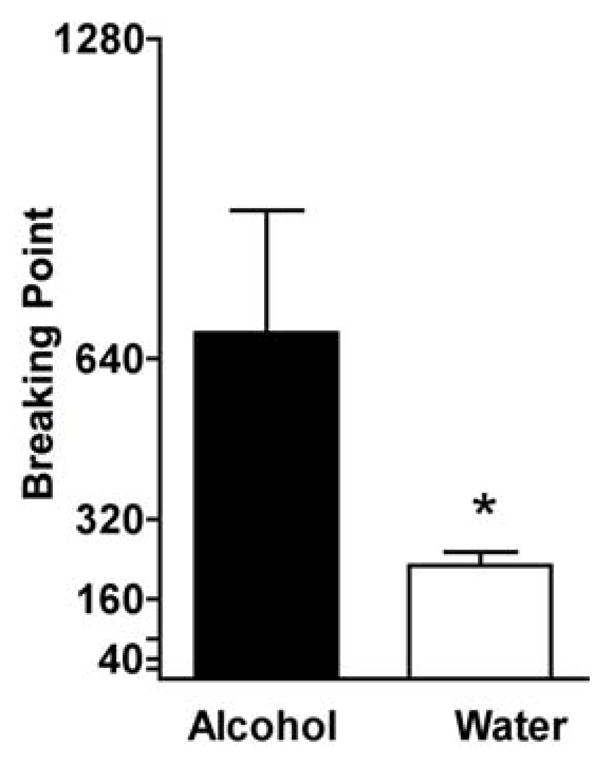

Progressive Ratio Procedure

Component 2 (Alcohol Seeking)

When the response requirement to gain access to alcohol was progressively increased across sessions, high levels of lever responding were maintained under the FR X schedule. When PR procedures were repeated under extinction conditions, alcohol cues continued to maintain lever responding under the FR X schedule, even when this led to access to water only. However, higher BPs were maintained by alcohol than by water. As shown in Fig. 4, the mean (± SEM) BP for alcohol was 692 (± 244.3). The mean BP for water was 224 (± 27.9). A paired t-test confirmed that the mean BP in the alcohol condition was significantly higher than in the extinction condition (t = 2.98, p<0.03).

Fig. 4.

Breaking points (BPs) completed under a progressive ratio (PR) response schedule in Component 2 to initiate Component 3 and gain access to alcohol (4% w/v) or water for self-administration. Alcohol-related cues were presented in both conditions. The mean of the last 4–5 PR evaluations conducted for each condition in each baboon were determined and data shown are the grand mean ± SEM for the group. * represents a significant (p<0.05) difference between the water and alcohol conditions.

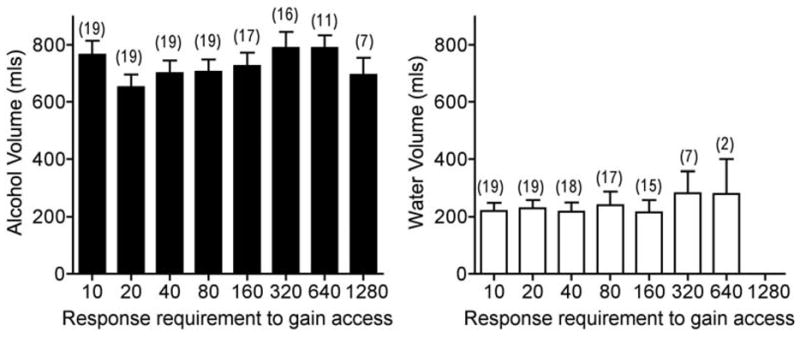

Component 3 (Self-administration)

Completion of the ratio requirement under the PR schedule initiated Component 3; drinks in Component 3 were contingent upon completion of the FR 10 requirement. Fig. 5 shows the mean volume of alcohol consumed in Component 3 following completion of each PR value in Component 2. The highest ratios completed were 1280 for alcohol and 640 for water and thus ratios from 10–1280 are included in Fig. 5; the number of times each ratio was completed is shown above each bar. The mean amount of alcohol consumed in Component 3 remained high and stable up to the BP (Fig. 5, left panel). That is, increasing the response cost to gain access to alcohol did not significantly alter its consumption once it was available. When water was substituted for alcohol, the total volume consumed decreased and was lower compared to the volume of alcohol consumed. The mean volume consumed of water also remained relatively stable regardless of ratio value in Component 2 (Fig. 5, right panel). ANOVAs of mean volume of alcohol or water consumed for each ratio confirmed there were no significant differences across ratio requirements within each condition. In addition, the volumes of alcohol and water consumed following completion of the PR response requirement were comparable to those observed during the baseline sessions that preceded each BP determination. The mean volume of alcohol consumed was 727.8 mL (±17.5 SEM). In comparison, the mean volume of water consumed following extinction was only 240.6 mL (±10.9 SEM).

Fig. 5.

Total volume of alcohol (Left panel) and water (Right panel) consumed in Component 3 after completion of progressive ratio response requirements in Component 2. The opportunity to self-administer drinks in component 3 was contingent upon completion of the fixed ratio (FR) response requirement in component 2. The FR response requirement was increased each day (10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640 and 1280) until the response requirement was not met and no drinks were obtained that day. Each FR response requirement is shown on the x-axis. Each bar represents the group mean ± SEM volume consumed during sessions in which the response requirement was completed resulting in alcohol or water availability for self-administration. Numbers in parenthesis above each bar represent the number of sessions included in the mean (i.e., number of sessions in which the response requirement was completed). These data correspond to the mean BP determinations shown in Fig. 4.

Blood Alcohol Levels (BAL)

Analysis of blood samples collected immediately following separate alcohol drinking sessions verified that the volume of 4% w/v alcohol consumed under the chained schedule of reinforcement produced relevant BALs. The mean g/kg of alcohol consumed was 0.93 g/kg and produced BALs in excess of 80 mg/dL (mean = 88.20 mg/dL; SEM ± 8.3). In humans, a BAL of 80 mg/dL is defined as the legal level for intoxicated driving in most of the USA.

DISCUSSION

Similar to our previous study using a chained schedule of alcohol reinforcement (Weerts et al., 2006) in the current study, alcohol (4% w/v) functioned as a reinforcer and baboons consumed biologically significant amounts of alcohol. Specifically, alcohol access maintained more responding during, and a shorter latency to complete, the FI requirement in Component 2 (seeking). Completion of the FI schedule resulted in more rapid access to the subsequent FR schedule, usually terminating the first link 9 – 10 minutes earlier than if no response occurred. In addition, in the present study, higher response requirements were completed (that is, higher BPs were obtained) to gain access to alcohol than water. Alcohol also maintained greater levels of lever responding (self-administration) and higher volumes of alcohol were consumed (consumption) in Component 3 when compared to the water vehicle. However, progressively increasing the response cost to gain access to the daily supply of alcohol did not reduce total intake suggesting that alcohol seeking and consumption can be dissociated.

As reviewed by (Meisch and Stewart, 1994), demonstration of continued alcohol intake greater than the alcohol vehicle is necessary to demonstrate alcohol reinforcement. In previous studies, concentrations of 4–8% w/v alcohol maintained more operant behavior and were consumed at greater quantities when compared to the water vehicle in baboons and macaques (Ator and Griffiths, 1992; Meisch and Stewart, 1994; Weerts et al., 2006). In the current study, when alcohol was available for consumption in Component 3 under a chained schedule of reinforcement, alcohol drinks maintained operant responses (i.e., lever presses and drinkometer contacts) and pharmacologically relevant doses of alcohol were consumed. All baboons consumed more alcohol than water when each solution was available for consumption under identical conditions. These data, as well as those reported by Weerts et al. (2006), demonstrate that the current procedure is effective in establishing and maintaining oral alcohol self-administration in baboons.

Although responding in Component 2 gradually decreased and latency to complete the FI requirement gradually increased during the extinction condition, responding persisted (the subjects failed to complete the FI response requirement on only 5% of sessions), even after 4 weeks of only water being available in Component 3. At the same time, responding and intake in component 3 was low. Seeking responses continued throughout the BP determinations, with BPs as high as 640 to gain access to water. During the extinction condition, a BP determination could take as long as 7 days (to reach a BP of 640), with at least 3 days between BP determinations. Thus, even after at least 30 days of extinction and an additional 30 or more days of water only during the BP determinations, responding during Component 2 persisted. This result is consistent with previous studies showing that stimuli previously paired with alcohol not only reinstate extinguished responding, but also continue to maintain that responding for many sessions. In a study reported by Ciccocioppo et al. (2001), rats were trained to respond for alcohol under an FR 1 schedule in the presence of distinct stimuli. Responding for alcohol was extinguished in a context different from training (that is, in the absence of the stimuli). The previously paired stimuli were then presented and a significant recovery of responding was observed. Responding remained significantly above extinction levels even after 50 days of stimulus presentation (with no alcohol access). Similarly, Zironi et al. (2006) reported that extinguished responding was recovered and continued for 3 weeks in the presence of stimuli previously paired with alcohol access. In contrast, responding recovered but decreased over the course of 3 weeks in the presence of stimuli previously paired with sucrose. This resistance to extinction suggests that responding during the alcohol seeking is largely under the control of stimuli/cues which have acquired conditioned reinforcing and/or eliciting properties, supporting previous research showing that environmental or contextual stimuli associated with drug use are an important contributing factor in relapse to drug use (Childress et al., 1992; Collins and Brandon, 2002; Crombag and Shaham, 2002). The length of time that responding persisted underscores the difficulty of modifying the function of environmental cues associated with alcohol use/abuse.

Weerts et al. (2006) reported that alcohol self-administration and consumption (but not seeking behaviors) under the chained schedule of reinforcement were sensitive to increases in response cost for each individual drink. Previous studies in rodents (Files et al., 1993), non-human primates (Ator and Griffiths, 1992; Foltin, 1998; Lemaire and Meisch, 1985) and humans (Spiga et al., 1997) have also demonstrated that the volume of alcohol consumed decreases as the response requirement increases. In contrast, in the present study, increasing the response requirement during the seeking component did not alter drinking behavior once access to alcohol was obtained, with intake remaining relatively constant. Studies using a variety of procedures and a variety of species (rats: (Heyman, 1997; Heyman et al., 1999; Petry and Heyman, 1995; Williams and Woods, 2000) rhesus monkeys: (Carroll et al., 2000), humans: (Goudie et al., 2007; Sumnall et al., 2004) have also demonstrated that alcohol intake is resistant to change, in that subjects will defend their alcohol intake despite large increases in response cost. That is, in economic terms, alcohol can be considered an “inelastic” commodity (Heyman, 2000). The present results are also consistent with (Czachowski and Samson, 1999) who reported that ethanol intake by rats was defended over a large number of days as cost for alcohol access increased (PR schedule) and then decreased (the ratio was returned to baseline).

Taken together, the resistance to change in the presence of the stimuli and the tendency to defend alcohol intake suggest that it will be essential to identify therapies that adequately address alcohol seeking as well as consumption. Obviously, an essential component of any successful therapy includes procedures focused on the reduction of consumption when presented with the opportunity to consume alcohol (e.g, extinction procedures, alternative reinforcement, and pharmacotherapies that produce aversive effects or blockade of alcohol effects). However, given the strength of the seeking response, therapies that focus primarily on consumption may face an unacceptable risk of relapse as they have not addressed the possibility that the patient will repeatedly and frequently seek opportunities to consume alcohol. Previous research has suggested that alcohol-related cues may be an important factor in relapse to heavy drinking (Drummond et al., 1990; Rohsenow et al., 1990). Moreover, results from our previous study in baboons (Weerts et al., 2006) indicate that abstinence may enhance reactivity to alcohol-related cues and increase alcohol seeking and subsequent alcohol consumption.

Like the extended chained schedule used in the current study, the initiation and maintenance of compulsive alcohol drinking in humans includes a sequence of responses and contingencies that occur in the presence of environmental cues. Taken together with previous data, the current findings indicate that the relationship between alcohol seeking and consumption appears to be dependent on the context in which alcohol-related cues are presented. The present data show that environmental manipulations can differentially alter seeking and consumption, which suggests that these behaviors can be dissociated under some conditions. In the current study, high levels of lever responding were maintained by cues associated with the opportunity to self-administer alcohol. The finding that increasing the response cost for the opportunity to self-administer alcohol did not reduce total alcohol consumption in the subsequent component suggests that behaviors associated with alcohol consumption can be dissociated from those involved in alcohol seeking. Although alcohol seeking and consumption can be dissociated during the maintenance of daily alcohol intake, there does appear to be a relationship between alcohol seeking and consumption in the context of returning to drinking after alcohol abstinence (Weerts et al., 2006).

In conclusion, these data show alcohol seeking behavior is highly resistant to change in the presence of cues previously associated with gaining access to alcohol, regardless of whether or not alcohol is subsequently available for consumption. Some current therapies (e.g., cue exposure therapy) acknowledge the importance of cues in maintenance of and relapse to problem drinking. However, for the most part, cue exposure therapy has not been shown to be more efficacious that other therapies (Conklin & Tiffany, 2002). This should not be taken to suggest that all cue-based therapies will be ineffective but rather suggest that we have not yet identified the necessary conditions for decreasing cue-maintained seeking behavior. Therefore, identification of interventions (behavioral/environmental or pharmacological) that decrease seeking behavior and craving should remain a major focus of preclinical and clinical research.

Acknowledgments

Supported NIH/NIAAA R21 AA13111 and R01AA015971. Dr. Goodwin’s effort was supported by NIH F32 DA019294.

References

- Ator NA, Griffiths RR. Oral self-administration of triazolam, diazepam and ethanol in the baboon: drug reinforcement and benzodiazepine physical dependence. Psychopharmacology. 1992;108:301–312. doi: 10.1007/BF02245116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M, Cosgrove K, Campbell U, Morgan A, Mickelberg J. Reductions in ethanol, phencyclidine, and food-maintained behavior by naltrexone pretreatment in monkeys is enhanced by open economic conditions. Psychopharmacology. 2000;148:412–422. doi: 10.1007/s002130050071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress A, Ehrman R, Rohsenow D, Robbins S, O'Brien C. Classically conditioned factors in drug dependence. In: Lowinson P, Luiz P, Millman RB, Langard G, editors. Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore: 1992. pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Angeletti S, Weiss F. Long-lasting resistance to extinction of response reinstatement induced by ethanol-related stimuli: role of genetic ethanol preference. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1414–1419. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins B, Brandon T. Effects of extinction context and retrieval cues on alcohol cue reactivity among nonalcoholic drinkers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:390–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comuzzie AG, Cole SA, Martin L, Carey KD, Mahaney MC, Blangero J, VandeBerg JL. The baboon as a nonhuman primate model for the study of the genetics of obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11:75–80. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addition treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombag H, Shaham Y. Renewal of drug seeking by contextual cues after prolonged extinction in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:169–173. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czachowski CL, Samson HH. Breakpoint determination and ethanol self-administration using an across-session progressive ratio procedure in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1580–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czachowski CL, Samson HH. Ethanol- and sucrose-reinforced appetitive and consummatory responding in HAD1, HAD2, and P rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1653–1661. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000036284.74513.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC, Cooper T, Glautier SP. Conditioned learning in alcohol dependence: implications for cue exposure treatment. Br J Addict. 1990;85:725–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Files FJ, Andrews CM, Lewis RS, Samson HH. Effects of ethanol concentration and fixed-ratio requirement on ethanol self-administration by P rats in a continuous access situation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW. Ethanol and food pellet self-administration by baboons. Alcohol. 1998;16:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(97)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudie A, Sumnall H, Field M, Clayton H, Cole J. The effects of price and perceived quality on the behavioural economics of alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, and ecstasy purchases. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainsey BM, Hubbard GB, Leland MM, Brasky KM. Clinical parameters of the normal baboons (Papio species) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Lab Anim Sci. 1993;43:236–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman G. Preference for saccharin-sweetened alcohol relative to isocaloric sucrose. Psychopharmacology. 1997;129:72–78. doi: 10.1007/s002130050164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman G. An economic approach to animal models of alcoholism. Alcohol Res Health. 2000;24:132–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman G, Gendel K, Goodman J. Inelastic demand for alcohol in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1999;144:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s002130050996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodos W. Progressive ratio as a measure of response strength. Science. 1961;134:943–944. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodos W, Kalman G. Effects of increment size and reinforcer volume on progressive ratio performance. J Exp Anal Behav. 1963;6:387–392. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katner SN, Flynn CT, Von Huben SN, Kirsten AJ, Davis SA, Lay CC, Cole M, Roberts AJ, Fox HS, Taffe MA. Controlled and behaviorally relevant levels of oral ethanol intake in rhesus macaques using a flavorant-fade procedure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:873–883. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128895.99379.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesey RE, Goldstein MD. Use of progressive fixed-ratio procedures in the assessment of intracranial reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1968;11:293–301. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1968.11-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby K, Lamb R, Iguchi M. Stimulus control of drug abuse. In: Baer DM, Pinkston EM, editors. Environment and Behavior. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1997. pp. 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire GA, Meisch RA. Oral drug self-administration in rhesus monkeys: interactions between drug amount and fixed-ratio size. J Exp Anal Behav. 1985;44:377–389. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.44-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaney MC, Leland MM, Williams-Blangero S, Marinez YN. Cross-sectional growth standards for captive baboons: II. Organ weight by body weight. J Med Primatol. 1993;22:415–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Weiss F, Gold LH, Caine SB, Schulteis G, Koob GF. Animal models of drug craving. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112:163–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02244907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisch RA, Stewart RB. Ethanol as a reinforcer: a review of laboratory studies of non-human primates. Behav Pharmacol. 1994;5:425–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N, Heyman G. Behavioral economics of concurrent ethanol-sucrose and sucrose reinforcement in the rat: effects of altering variable-ratio requirements. J Exp Anal Behav. 1995;64:331–359. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering C, Liljequist S. Cue-induced behavioural activation: a novel model of alcohol craving? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Sable HJ, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Recent advances in animal models of alcohol craving and relapse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of concurrent access to multiple ethanol concentrations and repeated deprivations on alcohol intake of alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1140–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Niaura RS, Childress AR, Abrams DB, Monti PM. Cue reactivity in addictive behaviors: theoretical and treatment implications. Int J Addict. 1990;25:957–993. doi: 10.3109/10826089109071030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Czachowski CL. Behavioral measures of alcohol self-administration and intake control: rodent models. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2003;54:107–143. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(03)54004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Slawecki CJ, Sharpe AL, Chappell A. Appetitive and consummatory behaviors in the control of ethanol consumption: a measure of ethanol seeking behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1783–1787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga R, Macenski MJ, Meisch RA, Roache JD. Human ethanol self-administration. I: The interaction between response requirement and ethanol dose. Behav Pharmacol. 1997;8:91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford D, LeSage MG, Glowa JR. Progressive-ratio schedules of drug delivery in the analysis of drug self-administration: a review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;139:169–184. doi: 10.1007/s002130050702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumnall H, Tyler E, Wagstaff G, Cole J. A behavioural economic analysis of alcohol, amphetamine, cocaine, and ecstasy purchases by polysubstance misusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren L, Everitt B. Behavioral and neural mechanisms of compulsive drug seeking. Eur J Pharmacology. 2005;526:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerts EM, Goodwin AK, Kaminski BJ, Hienz RD. Environmental cues, alcohol seeking, and consumption in baboons: effects of response requirement and duration of alcohol abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:2026–2036. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Woods J. A behavioral economic analysis of concurrent ethanol- and water-reinforced responding in different preference conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:980–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zironi I, Burattini C, Aicardi G, Janak PH. Context is a trigger for relapse to alcohol. Behav Brain Res. 2006;167:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]