Abstract

Introduction

A project of vocational rehabilitation was studied in Sweden between 1999 and 2002. The project included four public organisations: the social insurance office, the local health services, the municipal social service and the office of the state employment service. The aim of this paper was to analyse perceived barriers in the development of inter-organisational integration.

Theory

Theories of inter-professional and inter-organisational integration, and theories on organisational change.

Methods

In total, 51 semi-structured interviews and 14 focus group discussions were performed with actors within the project between 1999 and 2002. A thematic approach was used for the analysis of the data.

Results

Three different main themes of barriers emerged from the data: A Uncertainty, B Prioritising own organisation and C Lack of communication. The themes are interconnected in an intricate web and hence not mutually exclusive.

Conclusions and discussion

The barriers found are all related partly to organisational change in general and partly to the specific development of organisational integration. Prioritising of own organisation led to flaws in communication, which in turn led to a high degree of uncertainty within the project. This can be seen as a circular relationship, since uncertainty might increase focus on own organisation and lack of communication.

A way to overcome these barriers would be to take the needs of the clients as a point of departure in the development of joint services and to also involve them in the development of inter-organisational integration.

Keywords: inter-organisational integration, barriers, vocational rehabilitation, thematic analysis

Introduction and purpose

The term ‘integration’ often has positive connotations, but the definition is unclear [1–4]. Development of inter-organisational integration is a continuous process across professional boundaries as well as complex systems made up of the organisations involved. The effectiveness of integration is, therefore, difficult to evaluate [5–7]. Integration is sometimes described as a continuum from the lowest level of informal contacts, to the highest level where a common authority is established as responsible for management and operational decisions [4].

In rehabilitation, many different actors of the welfare system are involved. The division of responsibilities between the organisations is often unclear and the clients may ‘fall between stools’. Research in the area of inter-organisational integration between health care and other community agencies is also a relatively new field of interest [3].

To improve vocational rehabilitation, a number of experiments have been made in Sweden since the early 1990s aiming at an increased integration between different public organisations. In 1993, an experiment involving financial co-ordination was launched and conducted on a local basis by two organisations: the state run social insurance offices and the health services of the county councils [8]. The financial co-ordination was expanded in 1994 through a special legislation [9], which also included the municipal social services. This study is about a project included in such an experiment.

Mur-Veeman and her colleagues [10] suggest three concepts important for the analysis of integration as shared care: Structure is described in terms of organising for the implementation process. Power means to steer people into a desired direction and the one that is most powerful in integration work is the one whose resources are most needed by others. Culture is seen as a common base for values and understanding within a profession or organisation. These concepts are interdependent. Changes in organisational structures might for example imply changes in both cultures and power relations. Daily contacts are regarded as important in developing mutual trust and a common organisational culture. Involving the actors in developing the structure of a project may also increase the possibilities of a positive development. Structures often change during the process, and a good leadership is essential to achieve organisational change [11].

A new culture cannot be implemented by leadership alone, however. It evolves through common experiences of daily working [12]. Trust building is an important part of this process. It can be achieved when different organisations strive together towards a common goal. It is then important to rely on each other and have the needs of the individual in focus [13]. Hitherto there is little evidence of results in inter-organisational work. According to Huxham [14] this is due to the process of developing integration, which is difficult and resource-consuming. Previous studies have also shown that inter-organisational work often fails [15].

There is a lack of empirical studies of the implementation of innovations in service organisations since they have often been published in the so-called “grey” literature. Greenhalgh and colleagues [16 p.2] define implementation as “active and planned efforts to mainstream an innovation within an organisation”. The project studied can be regarded as an innovation in the organisation of human services according to the definition of the same authors: “a new set of behaviours, routines, and ways of working that are directed at improving health outcomes, administrative efficiency, cost effectiveness, or users' experiences and that are implemented by planned and coordinated actions.” According to Krause and Lund [17] there is also a lack of research regarding processes and barriers to implementation of programmes of vocational rehabilitation.

Barriers that impede how the implementation is done and barriers in inter-organisational and inter-professional work are intertwined in implementing a project of organisational integration. The results of a complex intervention are dependent on the structures, the processes as well as the context in which it is implemented [16]. As the world is continuously changing, it is impossible to see organisational development as a linear development through different stages [12]. Changing ways of working demand changing strategies on all levels: individual, group and organisation [18]. Inter-organisational integration mostly implies also an inter-professional integration at group level, as establishing groups with actors from different organisations involved is a common way of working in practise.

The pit-falls of developing inter-organisational integration are many and it is important to be aware of the difficulties that may arise during the process. In accordance with this the purpose of this paper was to explore the perceived barriers in a Swedish project of vocational rehabilitation aiming at development of inter-organisational integration.

Methods

Setting

A local vocational rehabilitation project in a community in the middle of Sweden was studied between 1999 and 2002. The project aimed at political and financial co-ordination in vocational rehabilitation and included the social insurance office, the local health services and the municipal social service. The office of the state employment service also participated although without financial commitment. A number of politicians, managers and specialists from the different organisations were involved in the project.

The goal of the project was on one hand to reduce the suffering of the individuals and on the other hand to use the joint resources more efficiently. The project targeted long-term sick municipal citizens between 16 and 64 years of age with diffuse or multiple problems, where at least two of the organisations were involved in their vocational rehabilitation. According to Konrad [4], this type of rehabilitation project could be seen as intermediary form of integration because it was a formalised relationship with common activities.

The project began its work to develop inter-organisational integration in 1998. Innovation and implementation of new ways of working was ongoing in an integrative process. This was done in a separate organisational structure with the aim of transferring the experiences into the participating organisations later. Decisions about how to distribute the economic resources from the different organisations were taken through a joint political board. Inter-organisational groups were formed consisting of specialists and managers at different levels, parallel to the traditional organisations. A simplified picture of the project organisation that was built to accomplish the work is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The organisation of the project.

A vision described in the project plan was to find new ways of working in collaboration in order to provide a more efficient rehabilitation of people with complex problems. There was some variation in views on goals, which has been presented previously [19]. At the end of the project 16 different inter-professional teams had been established for different activities and special localities outside the original organisations were used for these groups. The activities were targeted to different groups of individuals, for example unemployed people with psychiatric disorders. There were no changes of general routines or procedures in the original organisations.

Data collection

Qualitative methods were chosen to get a deeper understanding of the perceptions of the actors within the project. Semi-structured interviews [20,21] were performed each year 1999–2002. In total 51 individual interviews were performed. In addition, focus group discussions (FGDs) [22] were also performed with existing project groups at different levels of the organisation in 2000 and 2001 (Table 1). In total 68 persons were involved in 14 FGDs. The number of persons in each focus group varied between 2 and 9, with an average number of 5.

Table 1.

Interviews and focus group discussions (FGD) performed 1999–2002

| Year | Number of interviews | Number of FGD |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 21 | 0 |

| 2000 | 3 | 6 |

| 2001 | 5 | 8 |

| 2002 | 22 | 0 |

| Total | 51 | 14 |

Individual interviews make it possible to explore a phenomenon deeper [21] whereas FGDs are suitable for gaining knowledge of attitudes, experiences, perceptions and wishes [23]. The interaction between the participants also contributes to make different perceptions in a group evident [24].

The interview questions and the FGDs focused on goals, leadership, processes of organising, barriers and possibilities in developing inter-organisational integration. The interviews were held at the work places of the informants or in localities of the rehabilitation project. The interviews lasted from 40 minutes to 2 hours, with an average of 70 minutes. The FGDs were more even in time, each about 70 minutes. The interviews were conducted by the first author (UW) who was also the moderator of the FGDs.

All interviews and FGDs were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim by an independent typist. The interview guide was somewhat adapted according to the informant or group in focus. During each interview probing questions were asked in order to increase trustworthiness. Criteria for selection of informants were to get a broad range over the collaborating organisations as well as over the different levels of the project-organisation. Focus groups made it possible to involve more people to reflect on the work done. The project leader and key informants from the social service, the social insurance office, the local health care and the employment service were interviewed. The key informants were professionals, middle managers, top managers and politicians.

Informed consent was obtained from all the informants and confidentiality was assured in presenting the research. According to the in Sweden prevailing “Act on Ethics Review of Research Involving Humans”, approval from an Ethics Committee was not needed, and hence not applied for.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the interviewees for each year of the study.

Table 2.

Outline of informants in 1999 (n=21), 2000 (n=40), 2001 (n=36) and 2002 (n=22)

| Manager (male/female) |

Special (male/female) |

Politicians (male/female) |

Project management (male/female) |

Total number of informants |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |

| 1 (1/0) | 3 (2/1) | 3 (2/1) | 3 (2/1) | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| SIO | 2 (2/0) | 1 (1/0) | 1 (0/1) | 2 (0/2) | 3 (2/1) | 4 (0/4) | 5 (0/5) | 1 (0/1) | 0/0 | 4 (2/2) | 1 (0/1) | 1 (0/1) | 5 | 9 | 7 | 4 | ||||

| HC | 6 (3/3) | 4 (1/3) | 7 (1/6) | 4 (1/3) | 1 (1/0) | 3 (2/1) | 4 (1/3) | 2 (0/2) | 0/0 | 1 (1/0) | 1 (0/1) | 1 (0/1) | 7 | 8 | 12 | 7 | ||||

| Soc. | 4 (2/2) | 4 (2/2) | 6 (2/4) | 4 (1/3) | 1 (1/0) | 6 (1/5) | 3 (0/3) | 0 (0/0) | 0/0 | 1 (1/0) | 1 (1/0) | 1 (1/0) | 5 | 11 | 10 | 5 | ||||

| ES | 3 (1/2) | 3 (1/2) | 1 (1/0) | 3 (1/2) | 0 (0/0) | 6 (3/3) | 3 (2/1) | 0 (0/0) | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 3 | ||||

| Total | 15 (8/7) | 12 (5/7) | 15 (4/11) | 13 (3/10) | 5 (4/1) | 19 (6/13) | 15 (3/12) | 3 (0/3) | 0/0 | 6 (4/2) | 3 (1/2) | 3 (1/2) | 1 (1/0) | 3 (2/1) | 3 (2/1) | 3 (2/1) | 21 | 40 | 36 | 22 |

SIO=social insurance offices; HC=health care; Soc.=social services; ES=employment services.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis was used, inspired by Malterud [24]. This method of analysis is suitable for identifying new views within a research area. This was done in a step-wise manner and focused on barriers to integration throughout the project:

The transcripts of each of the 51 interviews and the 14 focus group discussions were read as a whole to get an overall impression and preliminary themes were formulated. The material was then coded into different meaning units. The contents of the meaning units was condensed and abstracted into themes and sub-themes. This was illustrated by quotations. After that the interviews were reread to confirm that the themes were in accordance with the raw data.

The data were analysed by the first author (UW) while the last author (IH) acted as co-reader. Discussions were held until consensus was reached.

Results

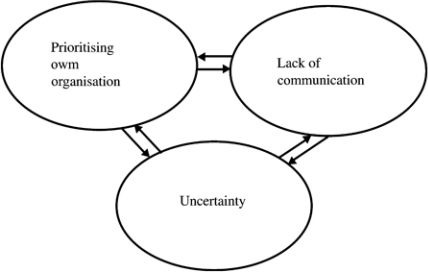

Three different main themes of barriers emerged from the data: A Uncertainty, B Prioritising own organisation and C Lack of communication. The main themes and sub-themes are described in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Themes and sub-themes in innovation and implementation of integration

| Themes | Sub-themes | Example of quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | Unclear goals Unclear leadership Unclear roles |

. . . how is the process of decision taking, who and where is what decided in this hierarchy where we are and above all which groups have the right to take decisions, it is difficult to know where to matters should be passed if we work a suggestion forward. To which group is it to go, I have no idea of it what so ever |

| Prioritising own organisation | Territoriality Financial and economic focus Distrust and different perspectives |

If we go on for a long time like this it might be better, but we are not there yet I think. People still fall between stools. Whose pigeon is this, we ask, who owns the responsibility? The shortcoming might not be due to [the project], but there has to be another approach in society, at authorities. It is a good start, but still a long way to go |

| Lack of communication | Lack of dialogue Lack of participation Lack of learning |

It is only things said in the hallway; now we closed that down, it will be your turn next, something like that. And why and how, you can feel it happens above |

Figure 2.

Themes.

It is important to point out that the themes are interconnected in an intricate web and hence not mutually exclusive, which is shown in Figure 2. Prioritising own organisation leads to a lack of communication with others. When dialogue and communication is not prevalent it leads to uncertainty about what is the meaning of different messages. Likewise, it is possible to start in any of the three barriers and see how they affect one another.

A Uncertainty

The aim of the project was diffuse from the start, and the overall goal was never discussed and made concrete. The length of the project was first only two years but was later extended twice which led to uncertainty in all parts of the project throughout the project time, even if it was more pronounced during the first two years.

A1 Unclear goals

The managers of the different organisations never specified how far they wanted to take the inter-organisational integration. There were different views about the goal varying from integration into one new common organisation to just facilitating transmission of information between existing organisations.

“It is a particularly infected matter if it turns up. How far should the practical integration between authorities go? My belief is that we have this unclear situation and a constant creation of new groups because that question is unsolved and not even discussed.”

(Specialist 2000)

In addition, the target group of the project was not clear. Specific target groups were identified by administrators and professionals, but the groups were unclear and overlapping. In 2002, some actors reflected on whether the project had reached the individuals most in need:

“. . .was the selection [of activities] a coincidence due to the fact that there happens to be an enthusiast in a specific organisation who is extremely keen about a specific matter. . .is that specific target group the one who is most in need?”

(Middle manager 2002)

A2 Unclear leadership

There was an uncertainty throughout the project about who was leading who. This was particularly evident between the project leader and the advisory group, where a struggle for power took place. The members of the advisory group wanted to be above the project leader hierarchically, but he claimed that his position was directly below the politicians.

“. . .this project should have had a steering committee consisting of us as directors of administration of different authorities, and my opinion is that the project leader should be subordinated to that steering committee. . . .the way it is now means that no kind of responsibility can be demanded from us within the advisory group, and I find this wrong because I am responsible for the things my organisation does or does not do.”

(Top manager 2002)

The project leader was recruited from one of the organisations involved. Early in the project there were also discussions about who was to pay the salary of the project leader, the organisation where he was previously employed or the political board of the project.

The professionals were also not sure of who was in command and who could decide over their working tasks. On one hand they had their ordinary manager and on the other hand they had the project leader.

“What is the process of decision making, what is decided by whom and where in this hierarchy of ours, and, above all, which groups have the right to make decisions? It is difficult to know where different matters should be sent if we work out a proposal. To what group should it go, I have no idea whatsoever.”

(Specialist 2000)

A3 Unclear roles

The lack of clarity concerning the project also made the mission of the appointed groups unclear. The actors were uncertain about their responsibilities and their authorities. At the outset of the project there were some co-operation groups at the professional level that had the task of bringing forward new ideas on how to handle certain groups of individuals, for example unemployed people with psychiatric disorders. The task was very broad and because the mandate of the group was unclear, the participants had to work all by themselves and did not know in what direction to go. After two years this co-operation group ceased.

The roles of the different groups in the project were diffuse. Sometimes the tasks of the groups overlapped and no one except the project management seemed to have a comprehensive view of the project. How different groups were interconnected was not evident. Groups changed names, came into being or ceased without anyone knowing how or why. It was also unclear how joint projects were chosen since no criteria for selection were decided.

The politicians had a discussion at the beginning of the project about whom or what they were to represent. Still in 2002 they had varying opinions about it.

“We had somewhat different opinions. . . some of us thought that we were representatives of our political parties in the first place. My opinion, however, was that we were representatives of the authority that had appointed us.”

(Politician 1, 2002)

“We have often discussed what we represent when we are at the board. . .. if you represent anything, it is first of all your party.”

(Politician 2, 2002)

B Prioritising own organisation

Throughout the project it was evident that the actors kept the perspective of their own organisation. The managers had a hard time raising themselves above their own budgets and seeing the benefits of the situation as a whole.

“Thinking from a client perspective, such [integration] should be at hand naturally. But it is not for some reason, because you choose your own box.”

(Top manager 2002)

The different groups within the project met about once a month. Some expressed that co-operation existed during the meetings but not in between.

“[the project] feels like a folder that you bring to meetings. During the time of the meetings you are very committed to tasks. Then you go home and put the folder back in its shelf again.”

(Specialist 2000)

B1 Territoriality

Both organisational and professional territoriality was seen. The age range of the target group, for example, was decided on the basis of the demands of the social insurance office due to their own organisation's age range in focus.

Guarding one's budget was important in 1999. There was a fear that someone else would get advantages at one's own cost. One manager expressed:

“It took some time before I understood the point of pooling everyone's budget together, so my first thought was, but God are you going to take all my money away. I cannot handle that. . .”

(Middle manager 1999)

The same person had a similar opinion still in 2002.

In most situations, the own organisation and its activities were prioritised. For example, some managers at high level were responsible for services delivered in several communities and they sometimes prioritised other meetings. When professionals were busy and lacking time, it was their ordinary tasks that were most important to them.

“. . .problems of drawing up boundaries arise. . .it is our greatest problem so far. . .all organisations are supposed to deal with integration, are they not? . . .this problem of drawing boundaries is increasing.”

(Project management 2002)

Some of the participants felt alienated, particularly those from the office of the employment service, possibly due to not being involved in the financial co-ordination. They were also introduced into the project later than the other actors, which was perceived as a negative factor.

B2 Formal and financial focus

Economic distributions between the organisations were made for each activity within the project according to which organisation would win the most from it. Importance was also given to mobilise support for each task at every hierarchical level of the organisations involved. A project organisation was, therefore, established as a parallel separate structure. A suggestion of a new activity within the project was to go through all of the groups at different levels to get opinions and a formal report from each one. In 2002, it was decided to create a minor steering group to each single activity, which also meant one more hierarchical level within the project.

Mobilisation of support led to a focus on formal and financial aspects. There were large groups and long meetings. The focus on the individuals served was of no priority:

“still. . .we talked about it today, we have somewhat lost focus on those who fall between stools.”

(Project management 2002)

A financial distribution of costs between the organisations involved was done according to the benefits from each specific project that was discussed. Several calculations were performed before decisions could be made to start an activity. The financial co-ordination system was regarded as complicated.

“The financial matters are so complicated that they almost need a controller, employed full-time.”

(Top manager 2001)

In almost every activity, one organisation had the main responsibility due to the financial decisions about who was to have most benefits from it. This made the other organisations lose interest in an activity where they were little involved.

Although the project was directed to target groups that fell ‘between stools’, the territoriality made the financial transactions the most complicated when no specific organisation could be regarded as responsible.

B3 Distrust and different perspectives

A common opinion among the actors was that territoriality already existed as a barrier within health care among different professions and different specialities, for example between psychiatry and primary care. There were also internal professional barriers perceived within the local community, for example between social and medical care for elderly people.

Health care was seen by some actors as a knowledge-oriented organisation with academic professionals. Some informants perceived a lack of co-operation from the doctors in health care. However, most work seemed to function well at group level. Outspoken conflicts occurred seldom but existed beneath the surface. The interviews once a year gave some of the participants moments of reflection on their work. During a focus group discussion in 2001 it became evident to a group of professionals that they had many different perspectives:

“. . .values within the different organisations, what views you have on human beings, what views you have on rehabilitation, the values of different expressions . . . our different authorisations, what we represent, how far we can stretch our regulations, what I am prepared to risk myself, when it comes to testing. . .the group was in a phase of denying differences. . .”

(Specialist 2002)

The commitment was deeper if an activity involved one's own organisation. In 2002, some signs of withdrawing from the co-operation groups were shown from the social care and the office of the employment services.

“People still fall between stools. Whose pigeon is this, we ask, who owns the responsibility?”

(Middle manager 2002)

In 2002, it was revealed that distrust had prevailed from the start, especially among managers, against the project leader, since he was recruited from one of the organisations involved. It was said that there had been a tight relationship between the project leader and the chairman of the political board, who was also a politician within the same organisation as the project leader came from. As a consequence some of the interviewees felt that the focus of the whole project was on that same organisation.

It was also obvious that there was a distrust between the project management and the top managers of the different organisations involved, and between the managers/professionals and the politicians. Some of the top managers suspected that their comments on proposals were censured before decisions were taken by the political board. They also felt sometimes that they were not being listened to.

“. . .the project leader is the one who decides what is to be written in the suggestion of the annual plan addressing the board, we do not. . . . this organisation is built in such a way that it is the project leader that takes the decision.”

(Top manager 2002)

C Lack of communication

Throughout the project there were flaws in communication, both vertically between different hierarchical levels and horizontally between groups. The lack of dialogue, the lack of participation and the lack of learning influenced each other in a vicious circle, most evident at the beginning of the project.

C1 Lack of dialogue

The formal structure of the project organisation made it slow to arrive at decisions. As mentioned before, every suggestion of an activity was supposed to pass through every group at every level of the project organisation.

Working groups were given tasks to perform, but they got no feedback from the project leader on their suggestions of solutions. This was most evident at the beginning of the project. In 2002, the groups seem to have accepted this at least partly and worked on without caring what happened above their level. Due to this, parallel work sometimes appeared.

“I have almost no contact with the co-operation groups. . .We did not know anything about it really, but it was on our table yesterday while the co-operation groups had had it twice for consideration.”

(Middle manager 2001)

Horizontal communication and co-operation between the different groups was limited. Working groups disappeared and new groups came into existence without the actors knowing how or why. This gave a feeling of uncertainty:

“It is only things said in the hallway, now we closed that down, it will be your turn next, something like that. And why and how, you can feel that it happens above yourself.”

(Specialist 2001)

C2 Lack of participation

The project management had an idea that the project was governed according to a bottom-up approach. The ideas were supposed to come from the professionals at the grass-root level and the managers were waiting for them to come. The professionals, however, felt that the project was governed top-down and they were waiting for the managers to act and give directions. As there was a lack of communication vertically, both managers and professionals waited for the others to take the initiative. The results were passivity.

“. . .we were to take care of the suggestions and ideas that arose in the interaction between the administrators and the clients. . . It is a good and a fine idea, but it did not work.”

(Project management 2002)

Most interviewees agreed about missing the employment service in the economic co-ordination. There was a common perception among the participants that this had led to an alienation of the employment service from the project.

“. . . there have been some intricate matters about who was to make certain decisions when it came to money. The employment service cannot, since they do not put any money into the project. And my opinion is that this has locked them in. . .the problem is that they have been sitting there somewhat set aside.”

(Top manager 2002)

There was no involvement of service users and the politicians did not see any need of discussion with them either. The initial study of potential target groups was oriented towards professionals, and no groups of clients or consumers were asked about their needs.

“we have got our knowledge and our inspiration from the profession; they are the ones that have come with ideas and suggestions. . ., and the political experiences that we bring, that is what has been steering us. Not the perspective of the individual in that sense that we have asked for their opinions. . .”

(Politician 2002)

C3 Lack of learning

Co-operation groups ceased and new ones were established without any knowledge transferred between them. There was no time for reflection built-in to the project. One-way communication dominated at meetings and there was no dialogue about lessons learned.

“. . .the time for planning and the time for reflection, it has been minimal, almost non-existent,. . . not reflecting upon what has been done. . ., or sitting down to make some planning for it.”

(Project management 2002)

Different activities were developed isolated from each other. The total picture of the different activities and their connections was unclear. Every working group was supposed to evaluate its own work, but there was not much commitment in doing that:

“We send in forms and then it is up to the project management to evaluate us. We have said that we do not take any interest in it, we are working on here to show our own importance, then it is up to them to evaluate it, according to their questions.”

(Specialist 2001)

Results and discussion

Results

The barriers found in this study were intertwined. They were partly related to organisational change and partly to the specific development of organisational integration with problems related to actors from different organisations working together.

Barriers to development of inter-organisational integration have previously been discussed by Huxham and Vangen [15] who among other things point to problems regarding the ambiguity of interrelationships and the complexity of inter-organisational integration. In the theory of collaborative advantage, they also point to many different themes as important to develop integration [15]: common aims, communication, commitment and determination, compromise, appropriate working processes, accountability, democracy and equality, resources, trust and power. This is somewhat different from the results of this study.

Themes that emerged out of the data as barriers to the development of integration were uncertainty, lack of communication and focus on own organisation in the present study. These themes are overlapping with those of Huxham and Vangen [15] and also the concepts described by Mur-Veeman and her colleagues [10]. They argue that the concepts of power, culture and structure are the most important in the implementation of shared care. Their opinion is that the concepts are interdependent in the sense that any of them may be the point of departure.

The themes in this study offer a somewhat other perspective, as they are intertwined with barriers to organisational change. This might be due to the use of a specific project organisation in this case. This is in agreement with the results of a recent dissertation [13] regarding the importance of change management in developing inter-organisational integration.

There were two separate goals of the project with a focus on clients as well as on financial resources. Focus on clients means in this case to get effective routines in inter-organisational integration to handle the rehabilitation of persons that have been in a grey zone between different organisations' areas of responsibility. Parallel controlling of costs as well as improving inter-organisational systems implies a potential conflict according to Hardy and colleagues [25]. Use of financial resources of each participating organisation was prioritised in this project as everyone was eager to keep one's own budget. This might help explaining the limited results in terms of starting different activities outside the original organisations instead of changing ways of working within and between them. In this way, it was easier to know who was to pay.

A finding specifically related to the development of inter-organisational integration was the focus on mobilisation of support at every level in all the organisations involved, which probably was due to the mistrust that, according to Huxham [15], often is prevalent in inter organisational work. In integration it should instead be of importance to trust one another in favour of developing joint services to clients. Trust is seldom prevalent from the start but trust-building can be developed through joint working and positive experiences that lead to enhanced trust in a positive loop [15]. In the project studied, there was joint working in inter-professional teams within each activity, but this was not spread into the original organisations.

The success of an innovation is also dependent on how the implementation is done [13, 16, 26]. The implementation of inter-organisational integration as an innovation is to a great extent dependent on leadership and ways of working [2, 13, 15]. Good leadership and communication are needed to facilitate organisational change, but there has not been so much research done in the area of leadership of inter-organisational integration [2]. According to Kotter [11], the leader should provide direction, unite individuals and motivate and inspire them. Leadership should communicate and help the participants to understand the overall vision and how different projects fit into the whole picture. When major change is imminent in an organisation, as is the case in development to inter-organisational integration, the leader should be able to coach his co-workers through the process of change. The importance of a project leader and learning from experiences has also been emphasised in studies of integration work [10, 13].

The leadership was unclear within the project studied, and the professionals were not sure of whom their leader was, the project leader or the manager within the original organisation. An evident barrier was the struggle for power between top managers and the project leader. The top managers were alienated from decisions in the project and later in the project they were reduced to an advisory group instead of a managerial group. This seems to have influenced their commitment to the project in a negative way. This is in contrast to another study of co-operation between public sector welfare organisations in vocational rehabilitation, where a conclusion was that involving higher level managers in collaborative work is important [27].

Uncertainty prevailed during the four years of study. There was also an absence of dialogue and reflection about factors of success or failures and what to learn from them, which probably contributed to putting the own organisation in focus instead of the service user. Within the project there was an organisational focus at the expense of the service users. The needs of the clients were not taken as a point of departure in the development of joint services, which would be important in order to see the common aim of the integration work [28–30]. Inter-organisational integration is too often carried out top-down. In the project studied this means that the service users were not involved in the developmental work [30].

It is not uncommon that attempts of change in organisations end up in doing new activities in old ways, due to powerful interests within the old context wanting to keep the status quo [31]. That is why organisational change is so important. Leaders have to contribute to create conditions for framing change and understand that even small changes in a complex context might lead to more important changes in the long run [32].

Uncertainty is not always negative though. With a flexible approach to new ideas and a continuous monitoring of the development, adjustments of directions are possible to do underway. Thus, with a positive interpretation, uncertainty might imply incompleteness and give way for creativity and testing [33]. However, the lack of reflection upon events and learning from experiences in the project studied made the uncertainty negative. There was no system developed for learning from mistakes, which is important in organisational change. The many organisational levels of the project were also barriers to creativity and learning to achieve new ways of working [31].

The project studied was huge and complex with many actors involved. A new project organisation was built to ensure participation. The barriers arising within the project made communication more difficult and might be questioned, since integration work is fragile and hard to achieve also without such extra difficulties [25, 29]. Inter-organisational groups dealing with clients need trust and support from leaders and management as a fuel to attain sustainability [29]. Changing structures is a natural part of a process of innovation and implementation, but the participants would certainly benefit from understanding the reasons for it. This was not communicated. However, understanding the barriers that arise is a way to overcome them in the work for inter-organisational integration aiming at improving vocational rehabilitation.

Methods

Since the context is Swedish and only one project was studied, the results cannot be generalised, but they might be transferable to similar situations. Data were collected between 1999 and 2002, but the barriers shown in the study are general and ought to be of value for the implementation of other integration projects.

The monitoring of the project during four years is a strength of the study, and so is the number of interviews and focus group discussions that were continuously performed during the period. The interviewer was the same (UW) every year, but she was otherwise not involved in the project.

This study has a perspective from the professionals of the organisations involved. In the future, it would be of great interest to make a study from a client's perspective on service fragmentation and lack of coordination. It would also be of interest to study what sort of support the clients would like to receive and what the implications of this would be for service delivery and decision-making.

Conclusions

Three general barriers were found in this study: prioritising own organisation, lack of communication and uncertainty. They are all related partly to organisational change in general and partly to the specific development of inter-organisational integration.

The results showed that focus on own organisation led to flaws in communication, which in turn led to uncertainty within the project. This can be seen as a circular relationship as uncertainty might increase the focus on own organisation and the lack of communication. When dialogue and communication is not prevalent, it might lead to uncertainty about the aims and the importance of integration and thus prioritising of the own organisation.

A way to overcome these barriers would be to take the needs of the service users as a point of departure in the development of joint services and to also involve them in the development of inter-organisational integration. This could be done for example through focused group discussions with target groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the participating informants. Grants were received from the Nordic School of Public Health in Göteborg, Centre for Public Health in Stockholm and the Swedish Research Council.

Contributor Information

Ulla Wihlman, Nordic School of Public Health, P.O. Box 12133, SE-402 42 Göteborg, Sweden and Stockholm Centre for Public Health, P.O. Box 17533, SE-118 91 Stockholm, Sweden.

Professor Cecilia Stålsby Lundborg, Nordic School of Public Health, P.O. Box 12133, SE-402 42 Göteborg, Sweden and Associate Professor Division of International Health (IHCAR), Department of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden.

Professor Runo Axelsson, Nordic School of Public Health, P.O. Box 12133, SE-402 42 Göteborg, Sweden.

Inger Holmström, Department of Public Health and Caring Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala Science Park, SE-751 85 Uppsala, Sweden.

Reviewers

Jan Ekholm, MD PhD, Professor of Rehabilitation Medicine, Karolinska Institutet Department of Clinical Sciences at Danderyd Hospital, Division of Rehabilitation Medicine, Stockholm, Sweden

Nicole van Erp, MA, Research associate, Trimbos Institute, Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction, Utrecht, Netherlands

One anonymous reviewer

References

- 1.Leichsenring K. Developing integrated health and social care services for older persons in Europe. [cited 2007 Nov 15];International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2004 Sep 4;3 doi: 10.5334/ijic.107. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armistead C, Pettigrew P, Aves S. Exploring leadership in multi-sectoral partnerships. Leadership. 2007;3(2):211. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axelsson R, Axelsson SB. Integration and collaboration in public health – a conceptual framework. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2006 Jan-Mar;21(1):75–88. doi: 10.1002/hpm.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konrad E. A multidimensional framework for conceptualizing human services integration initiatives. New Directions for Evaluation. 1996;69:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowling B, Powell M, Glendinning C. Conceptualising successful partnerships. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2004 Jul;12(4):309–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von dem Knesebeck O, Joksimovic L, Badura B, Siegrist J. Evaluation of a community-level health policy intervention. Health Policy. 2002 Jul;61(1):111–22. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirkis J, Herrman H, Schweitzer I, Yung A, Grigg M, Burgess P. Evaluating complex , collaborative programmes: the partnership project as a case study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;35(5):639–46. doi: 10.1080/0004867010060513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Socialstyrelsen, Riksförsäkringsverket. FINSAM-en slutrapport. [FINSAM – a final report]. Stockholm: Finansiell samordning; 1991. p. 1. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Socialstyrelsen, Riksförsäkringsverket. SOCSAM – ett försök med politisk och finansiell samordning. En slutrapport. [SOCSAM – a trial with political and financial co-ordination A final report]. Stockholm: Finansiell samordning; 2001. p. 1. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mur-Veeman I, Eijkelberg I, Spreeuwenberg C. How to manage the implementation of shared care: a discussion of the role of power, culture and structure in the development of shared care arrangements. Journal of Management in Medicine. 2001;15(2):142–55. doi: 10.1108/02689230110394552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotter JP. Leading change. Boston (MA): Harvard Business School Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvesson M. Understanding organizational culture. London: Sage Publications Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eijkelberg IMJG. Viewpoints of managers, care providers and patients. University of Maastricht; 2007. Key factors of change processes in shared care. [PhD thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huxham C. Theorizing collaboration practice. Public Management Review. 2003;5(3):401–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huxham C, Vangen S. Managing to collaborate: the theory and practice of collaborative advantage. London: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, MacFarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause N, Lund T. Returning to work after occupational injury. In: Barling J, Frone M, editors. The psychology of workplace safety. Washington DC: APA Books; 2004. pp. 265–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003 Oct 11;362(9391):1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandström U, Axelsson R, Stålsby Lundborg C. Inter-organisational integration for rehabilitation in Sweden: variation in views on long-term goals. [cited 2007 Nov 15];International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2004 Dec 4;15 doi: 10.5334/ijic.112. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krueger RA. Focus groups. 2nd ed. California: SAGE Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbour RS, Kitzinger J. Developing focus group research: politics, theory and practise. London: SAGE Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malterud K. Kvalitativa metoder i medicinsk forskning. [Qualitative methods in medical research]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1998. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy B, Mur-Veeman I, Steenbergen M, Wistow G. Inter-agency services in England and the Netherlands. A comparative study of integrated care development and delivery. Health Policy. 1999;48:87–105. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(99)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein KJ, Sorra JS. The challenge of innovation implementation. The Academy of Management Review. 1996;21(4):1055–80. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindqvist R, Grape O. Vocational rehabilitation of the socially disadvantaged long-term sick: inter-organizational co-operation between welfare state agencies. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 1999;27:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Øvretveit J. Quality in health promotion. Health Promotion International. 1996;11:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn JB. Intelligent enterprise: a knowledge and service based paradigm for industry. New York: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glendinning C. Breaking down barriers: integrating health and care services for older people in England. Health Policy. 2003;65:139–51. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan G. Images of organization. The executive edition. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraser SW, Greenhalgh T. Coping with complexity: educating for capability. British Medical Journal. 2001 Oct 6;323(7316):799–803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahlin-Andersson K. Oklarhetens strategi. Organisering av projektsamarbete. [The strategy of uncertainty. Organising of collaboration in projects]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1989. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]