Abstract

Background

Established traumatic memories have a selective vulnerability to pharmacologic interventions following their reactivation that can decrease subsequent memory recall. This vulnerable period following memory reactivation is termed reconsolidation. The pharmacology of traumatic memory reconsolidation has not been fully characterized despite its potential as a therapeutic target for established, acquired anxiety disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase is a critical regulator of mRNA translation and is known to be involved in various forms of synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation. We have examined the role of mTOR in traumatic memory reconsolidation.

Methods

Male C57BL/6 mice were injected systemically with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin (1 – 40 mg/kg), at various time points relative to contextual fear conditioning training or fear memory retrieval, and compared to vehicle or anisomycin-treated groups (N = 10–12 in each group).

Results

Inhibition of mTOR via systemic administration of rapamycin blocks reconsolidation of an established fear memory in a lasting manner. This effect is specific to reconsolidation as a series of additional experiments make an effect on memory extinction unlikely.

Conclusions

Systemic rapamycin, in conjunction with therapeutic traumatic memory reactivation, can decrease the emotional strength of an established traumatic memory. This finding not only establishes mTOR regulation of protein translation in the reconsolidation phase of traumatic memory, but also implicates a novel, FDA-approved drug treatment for patients suffering from acquired anxiety disorders such as PTSD and specific phobia.

Keywords: mTOR, reconsolidation, consolidation, fear conditioning, posttraumatic stress disorder, extinction, learning and memory, rapamycin

Introduction

Newly formed fear memories undergo a process of consolidation immediately following training which is required for long-term maintenance of the memory trace (Abel and Lattal, 2001; Dudai, 2004; Nader, Schafe, and Le Doux, 2000a). Protein synthesis inhibitors and other pharmacologic agents interfere with memory consolidation (Bourtchouladze, Abel, Berman, Gordon, Lapidus, and Kandel, 1998; Davis and Squire, 1984; Flexner, Flexner, De La Haba, and Roberts, 1965; McGaugh, 2000). Also, growing evidence suggests that fear memories have a selective sensitivity to pharmacologic interventions, including protein synthesis inhibitors, after reactivation, that negatively affect subsequent memory (Nader et al., 2000a; Pedreira and Maldonado, 2003; Przybyslawski and Sara, 1997; Sara, 2000; Schneider and Sherman, 1968; Suzuki, Josselyn, Frankland, Masushige, Silva, and Kida, 2004; Tronel and Alberini, 2007). Pharmacologic vulnerability to the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin following reactivation empirically defines the “reconsolidation” phase of memory (Abel and Lattal, 2001; Dudai, 2004; Lattal and Abel, 2004; Nader et al., 2000a). Established memories may also be affected during reactivation through extinction, another process amenable to pharmacologic manipulation (Bouton, 1993; Cai, Blundell, Han, Greene, and Powell, 2006; Myers and Davis, 2002). Although the processes of consolidation, reconsolidation, and extinction require overlapping molecular pathways, recent studies suggest that there are distinct molecular processes involved in each (Bouton, 1993; Lee, Everitt, and Thomas, 2004; Myers and Davis, 2002).

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase regulates a subset of protein synthesis in neurons at the translational level through phosphorylation of several intracellular targets including p70 S6 kinase (p70S6K) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding proteins (4EBPs) (Raught, Gingras, and Sonenberg, 2001). These substrates are involved in the initiation of protein translation (Hay and Sonenberg, 2004). The mTOR pathway was first implicated in synaptic plasticity when rapamycin, a selective inhibitor of mTOR activity (Casadio, Martin, Giustetto, Zhu, Chen, Bartsch, Bailey, and Kandel, 1999; Hay and Sonenberg, 2004; Takei, Inamura, Kawamura, Namba, Hara, Yonezawa, and Nawa, 2004; Takei, Kawamura, Hara, Yonezawa, and Nawa, 2001) was shown to block long-term facilitation in Aplysia (Casadio et al., 1999) and to prevent LTP in the rat hippocampus (Tang, Reis, Kang, Gingras, Sonenberg, and Schuman, 2002). While several studies have examined effects of mTOR inhibition on synaptic plasticity in vitro, few have examined the role of mTOR kinase in learning and memory in vivo (Bekinschtein, Katche, Slipczuk, Igaz, Cammarota, Izquierdo, and Medina, 2007; Parsons, Gafford, and Helmstetter, 2006).

These prior studies were the first to demonstrate a requirement for mTOR activity in the hippocampus or amygdala in fear memory acquisition or consolidation (Bekinschtein et al., 2007; Parsons et al., 2006). Our studies confirm and extend the effect of mTOR inhibition on fear memory consolidation to systemic application. In addition, one of these reports showed that direct infusion of rapamycin into the amygdala following a single memory reactivation lead to a reduction in recall when tested 24 h later. While the authors interpreted this as an effect of intra-amygdala rapamycin on reconsolidation, they provided no additional evidence 1) to distinguish an effect of rapamycin on augmenting extinction versus inhibiting reconsolidation, for example by demonstrating resistance to reminder shock, 2) to compare the magnitude of rapamycin’s effect with that of anisomycin which empirically defines reconsolidation, 3) to determine if the effect of rapamycin, like that of anisomycin, lasts beyond 24 hours, or 5) to determine whether memory reactivation was actually required for rapamycin’s effect on subsequent memory recall. These are critical experiments required to demonstrate an effect of a drug on the reconsolidation process. In addition, while understanding the role of rapamycin specifically in the amygdala is important mechanistically, in order to prove potential clinical utility the drug must work when given systemically.

This study is the first to definitively demonstrate that systemic inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin following a single traumatic memory reactivation inhibits reconsolidation of contextual fear conditioning in a lasting manner. Importantly, our experiments distinguish between effects on extinction versus reconsolidation. Furthermore, we provide evidence that the rapamycin effect is comparable in magnitude to that of anisomycin early after memory reactivation. Interestingly, the effect of rapamycin on memory reconsolidation is significantly larger than anisomycin’s effect 21 days following reactivation. These findings provide a rodent model for treatment of established, acquired anxiety disorders in humans based on inhibition of reconsolidation.

Methods and Materials

Behavior

Fear conditioning was performed essentially as described previously (Cai et al., 2006). Briefly, mice were placed in the shock context for 2 min, then a 30 s, 90 dB tone co-terminating in a 2 s, 0.5 mA foot shock was delivered twice with a 1 min interstimulus interval (Fig. 3b/c = 1 shock). Mice remained in the context for 2 min before returning to their home cage. Freezing behavior was monitored at 10 s intervals by an observer blind to the experimental manipulation. To test for contextual memory 24 h after training, mice were placed into the same training context for 5 min and scored for freezing behavior every 10 s. Student’s t-test was used for two-group comparisons, whereas one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey or planned comparison tests was used in experiments with multiple groups. Significance was taken as p < 0.05.

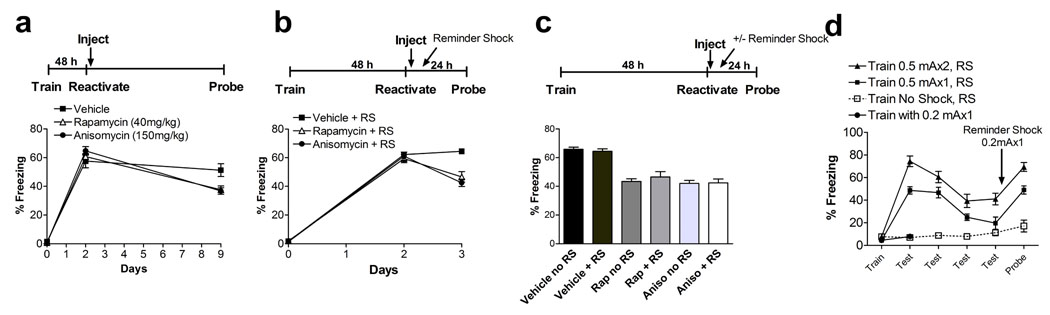

Figure 3. Systemic rapamycin decreases fear memory reconsolidation.

a Post-reactivation injection of rapamycin or anisomycin following a single memory reactivation significantly reduced subsequent recall of a fear memory 7 days later (probe) in the absence of drug. This effect was equivalent to that of the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin. One-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of condition (F2,33 = 6.19, p = 0.0052), post hoc Tukey’s test indicated that vehicle differed from rapamycin and anisomycin, which didn’t differ (veh vs. rap, p = 0.016, vs. aniso, p = 0.0099, aniso vs. rap, p = 0.98) b, Reminder shock had no effect on post-reactivation rapamycin effect on subsequent memory, similar to anisomycin. One-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of condition during probe test (F2,33 = 17.73, p = 0.000006). Post hoc Tukey’s test indicated that vehicle differed from rapamycin and anisomycin treated mice, while rapamycin and anisomycin effects were equivalent (veh vs. rap, p = 0.00032, vs. aniso, p = 0.00013, aniso vs. rap, p = 0.54). RS = reminder shock. c, Comparison of reminder shock (+ RS) versus no-reminder shock (no RS) groups on the final day of testing for each drug. One-way ANOVA: main effect of condition, F5,66 = 23.84, p < 0.00001, post hoc Tukey comparisons, veh no RS vs. veh + RS, p = 0.99, rap no RS vs. rap + RS, p = 0.93, aniso no RS vs. aniso + RS, p = 0.99. No significant differences were observed during training or reactivation (48 h) across groups (p > 0.5). N = 12 in all above groups. d, Reminder shock used in b & c (0.2 mAx1) does not cause significant learning/memory in naïve mice tested 24 h after training (solid circles). The same 0.2 mAx1 reminder shock reinstates contextual fear memory recall following 4 days of extinction after training with one (closed squares) or two (closed triangles) pairings of 0.5 mA footshocks with context.

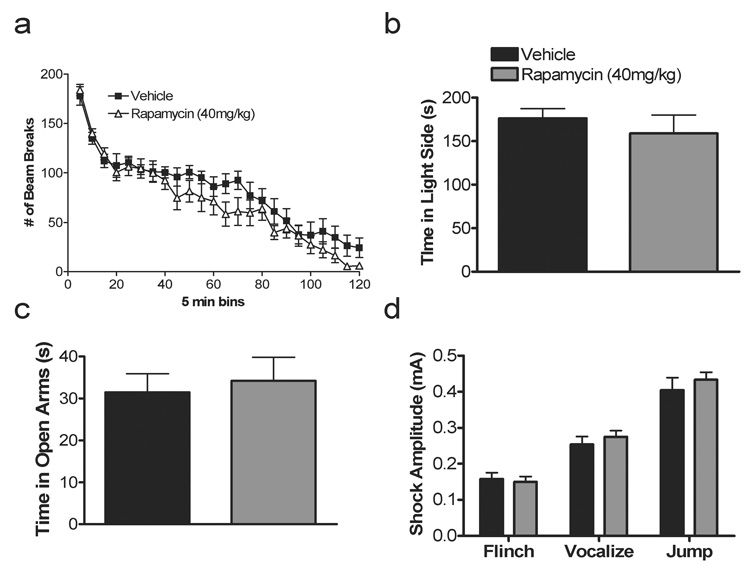

We examined for effects of rapamycin on locomotor activity, anxiety, and nociception to ensure our effects on memory were selective. Elevated plus maze, dark/light and locomotor behavior were performed as described (Cai et al., 2006; Powell, Schoch, Monteggia, Barrot, Matos, Feldmann, Sudhof, and Nestler, 2004). For the elevated plus maze, however, videotracking software from Noldus (Ethovision 2.3.19) recorded time spent in the open and closed arms and number of open and closed entries. Footshock sensitivity was performed by placing mice in the contextual conditioning chamber for a 2 min habituation period followed by a 2 s footshock every 30 s (Powell et al., 2004). Shock amplitude started at 0.05 mA and was incremented by 0.05 mA with successive stimuli. The stimulus amplitudes required to elicit behavioral responses of flinching, jumping and vocalizing were recorded. Student’s t-test was used for two-group comparisons while two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used to analyze locomotor activity.

Drug preparation/administration

Fresh solutions of rapamycin and anisomycin were made with 5% ethanol, 4% PEG400 and 4% Tween 80 in sterile water the day of the experiment. Mice were weighed on the morning of the experiment and injected intraperitoneally with volumes ranging from 0.3 to 0.4 ml. Doses used were rapamycin 1, 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg based on pilot data. Twenty and 40 mg/kg were used in follow-up experiments because of their effects in our dose-response curve (see Fig. 1c). A dose of 150 mg/kg of anisomycin was chosen to block reconsolidation based on our previous studies (Cai et al., 2006).

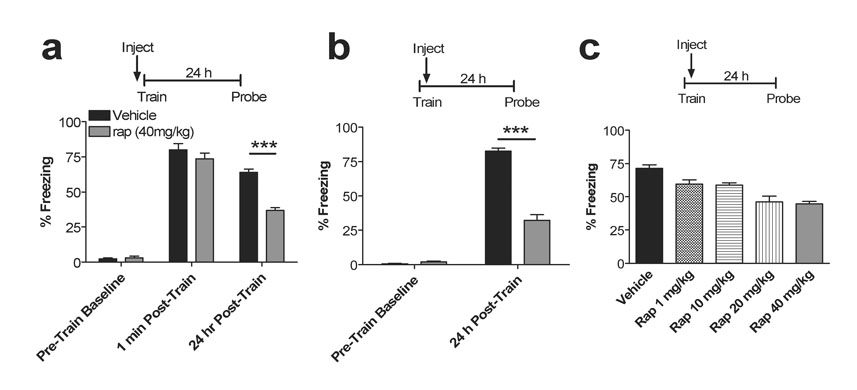

Figure 1. Systemic rapamycin inhibits fear memory consolidation.

a, Injection of rapamycin 30 min prior to training impairs recall. Pre-train baseline (veh vs. rap, p = 0.54), 1 min post-train (veh vs. rap, p = 0.30), 24 h post-train (veh vs. rap, p < 0.0001). N = 12 in both groups. Legend applies to panels a, b. b, Injection of rapamycin 2 min following training impairs recall 24 h later (veh vs. rap, p < 0.0001). N= 12 in both groups. c, A dose-response curve for rapamycin administered immediately after training is shown. Bars represent percentage of freezing 24 h after training. A one-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of drug (F4,45 = 14.29, p < 0.0001; post hoc Tukey’s test, vehicle vs. 1.0 mg/kg, p = 0.044, vs. 10 mg/kg, p = 0.023, vs. 20 mg/kg, p = 0.00014, vs. 40 mg/kg, p = 0.00013). Rap 1.0 mg/kg does not differ from 10.0 mg/kg, (p = 0.99) but differs from 20 and 40 mg/kg, (p = 0.018, 0.0063 respectively). Rap 10 mg/kg differs from 20 and 40 mg/kg (p = 0.035, 0.013, respectively). Rap 20 mg/kg does not differ from 40 mg/kg (p = 0.99). No significant differences were observed during training (Pre-Train Baseline) across groups (p>0.05). N=10 in all groups. Error bars represent SEM in all figures.

Results

Rapamycin Blocks Traumatic Memory Consolidation

Our initial experiments were aimed at confirming a systemic effect of rapamycin on traumatic memory consolidation and performing a dose-response curve to determine effective systemic doses. To confirm the role of mTOR in acquisition/consolidation of a contextual fear memory, male C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with rapamycin (40 mg/kg) and trained thirty minutes later in a classical fear conditioning paradigm in which a novel environment is paired with footshock. Prior to training, the rapamycin-treated group and vehicle-treated group displayed similar levels of freezing (Fig. 1a; pre-train, p = 0.54). Importantly, freezing immediately after initial training was similar in rapamycin-treated mice and vehicle controls, suggesting normal acquisition and immediate short-term recall of footshock/context association (Fig. 1a; 1 min post-train, p = 0.30). However, 24 h later, the rapamycin-treated mice exhibited significantly decreased memory upon re-exposure to the training environment (Fig. 1a, 24 h, p < 0.0001). Similarly, when injected immediately after training, rapamycin-treated mice also showed decreased learning compared to vehicle-treated mice 24 h after training (Fig. 1b, p < 0.0001). In a dose-response curve using mice injected with 1, 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg after training, all groups showed significantly reduced memory 24 h later compared to vehicle-treated mice (ANOVA: F4, 45=14.29, p < 0.0001; veh vs. 1, 10, 20, 40 mg/kg, p = 0.044, 0.023, 0.00014, 0.00013, respectively). In addition, 20- and 40 mg/kg-treated animals exhibited significantly less memory compared to 1.0 (20 vs. 1 mg/kg, p = 0.018; 40 vs. 1 mg/kg, p = 0.0063) and 10 mg/kg (20 vs. 10 mg/kg, p = 0.035; 40 vs. 10 mg/kg, p = 0.013) dosages 24 h post-training (Fig. 1c). Thus, systemic inhibition of the mTOR pathway via rapamycin significantly reduces contextual fear memory consolidation.

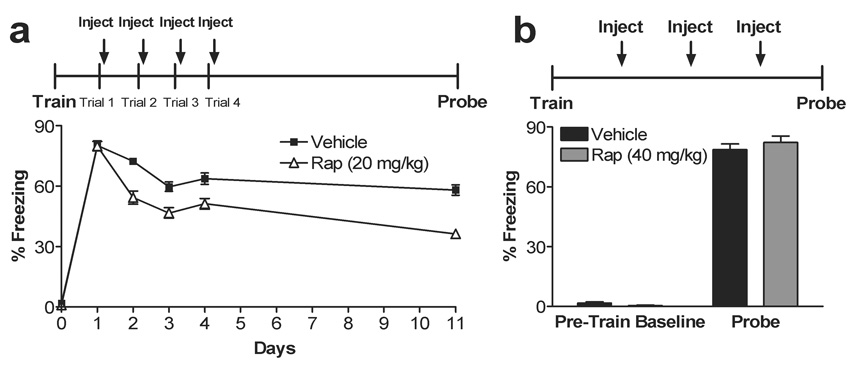

Rapamycin Inhibits Traumatic Memory Reconsolidation

To determine if systemic rapamycin decreases an established traumatic memory, we next examined the effect of systemic rapamycin injection following memory reactivation. To do this, we trained mice in the contextual fear conditioning paradigm. Twenty-four h later, re-exposure to the training environment elicited significant fear responses in both rapamycin and vehicle-treated groups, indicating successful reactivation of contextual fear memory (Fig. 2a, day 1, p = 0.91). Immediately following reactivation, mice were injected with rapamycin (20 mg/kg) or vehicle and tested 24 h later. Rapamycin-treated mice showed a significant decrease in subsequent fear memory compared to vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 2a, day 2, p < 0.0001). In these initial studies, reactivation plus rapamycin treatment was repeated daily for 4 days and fear memory 7 days following the last treatment was significantly reduced in rapamycin-treated compared to vehicle treated controls (Fig. 2a, day 11). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed main effects of drug (F1,38 = 51.57, p < 0.0001), day (F4,152 = 56.12, p < 0.0001), and interaction between drug and day (F4,152 = 5.79, p = 0.00023). Student’s t-test of days 1–4 (p = 0.91, p < 0001, p = 0.00064, p = 0.0026, respectively) and day 11 (p < 0.0001) indicate reduced memory in the rapamycin-treated animals. Importantly, the effects of rapamycin administration following memory reactivation were dependent on reactivation of the memory and were not simply a prolonged effect of rapamycin administration alone (Fig. 2b, p = 0.43).

Figure 2. Systemic rapamycin inhibits reconsolidation or facilitates extinction.

a, Multiple trial post-training rapamycin inhibits subsequent fear memory recall. Repeated injection of rapamycin 2 min after extinction trials for 4 days impairs subsequent retrieval following a single pairing. This effect is long lasting as subsequent memory recall tested in the absence of rapamycin 7 days after the last extinction trial remains impaired. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed main effects of drug (F1,38 = 51.67, p < 0.0001), day (F4,152 = 56.12, p < 0.0001), and interaction between drug and day (F4,152 = 5.79, p = 0.00023). Student’s t-test of days 1–4 and 11 indicate p = 0.91, p < 0.0001, p = 0.00064, p = 0.0026, p < 0.0001, respectively). N = 20 in both groups. b, Reactivation of a fear memory is necessary for the rapamycin effect on subsequent recall. Multiple daily injections of rapamycin in the absence of memory reactivation do not affect subsequent memory recall (veh vs. rap, p = 0.43). No significant differences were observed during pre-training across groups (p > 0.05). N=10 in both groups.

To determine if a single pairing of systemic rapamycin with reactivation affects subsequent recall of an established fear memory similar to the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin, we trained animals, waited 48 h to insure complete initial consolidation, and reactivated the memory. Immediately after reactivation, mice were injected with rapamycin (40 mg/kg), anisomycin (150 mg/kg, for comparison), or vehicle and tested 7 days later in the absence of the drug. Vehicle-treated animals showed normal learning while rapamycin- and anisomycin-treated animals showed equally reduced subsequent memory (Fig. 3a; ANOVA: main effect of drug, F2,33 = 6.19, p = 0.0052; post hoc Tukey tests, veh vs. rap, p = 0.016, veh vs. aniso, p = 0.0099, aniso vs. rap, p = 0.98). Thus, like anisomycin, systemic rapamycin injection following a single memory reactivation can reduce subsequent recall for at least 7 days.

We next sought to determine whether the post-reactivation effect of rapamycin on subsequent memory recall was due to augmenting extinction or interfering with reconsolidation. Extinction of a fear memory can be reversed by exposure to a “reminder shock” that is below the threshold for de novo fear conditioning, whereas reconsolidation effects cannot (Cai et al., 2006; Duvarci and Nader, 2004). In addition, extinction effects may spontaneously revert within 7 days, unlike effects of anisomycin on reconsolidation(Cai et al., 2006). Indeed, we have shown that systemic corticosterone injected following a single memory reactivation trial can lead to decreased subsequent memory recall, an effect that could have been interpreted as a reconsolidation effect had it not been for an additional series of experiments proving that corticosterone is acting on extinction (Cai et al., 2006).

To distinguish between effects on extinction versus reconsolidation, we trained animals, reactivated the memory 48 h later, then immediately injected rapamycin, anisomycin (for comparison), or vehicle. In half of the animals, however, we interposed a subthreshold (0.2 mAx1) reminder shock 4 h after memory reactivation/injection. The other half of the animals was placed into the same shock box without footshock at the same time. Mice were then tested 24 h later in the absence of drug. As expected for an effect on reconsolidation, rapamycin-treated animals were unaffected by the reminder shock, similar to the anisomycin-treated group (Fig. 3b, 3c ANOVA: F2,33 = 17.73, p = 0.0001, post hoc Tukey tests; veh + RS vs. rapamycin + RS, p = 0.00032, vs. aniso + RS, p = 0.00013; Fig. 3c, ANOVA: F5,66 = 23.84, p < 0.0001, post hoc Tukey comparisons, veh no RS vs. veh + RS, p = 0.99, rap no RS vs. rap + RS, p = 0.93, aniso no RS vs. aniso + RS, p = 0.99). The reminder shock of 0.2 mAx1 with a 4 h delay was empirically determined and does not result in significant contextual fear conditioning in naïve mice (Fig. 3d), and can robustly reverse and established extinguished contextual fear memory (Fig. 3d). The similarity of the rapamycin effect to that of anisomycin as well as the resistance to reminder shock argue for an effect of rapamycin on reconsolidation rather than on extinction (in contrast to similar experiment using corticosterone)(Cai et al., 2006).

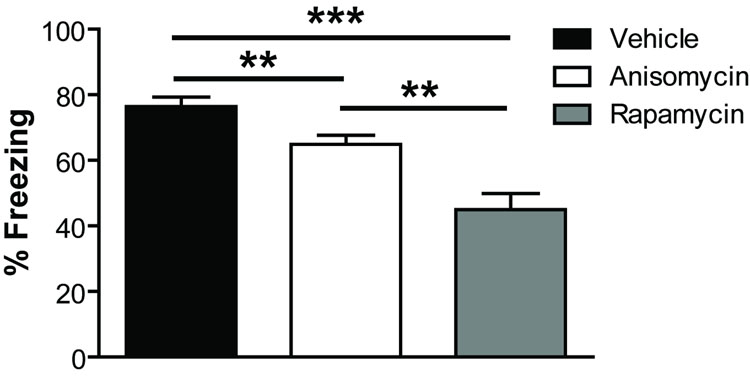

Next, we assessed whether the effects of a single post-reactivation injection of rapamycin were long-lasting. We trained animals and reactivated the memory 24 h later. Immediately after reactivation, mice were injected with rapamycin (40 mg/kg), anisomycin (150 mg/kg, for comparison), or vehicle and tested 21 days later in the absence of the drug. Vehicle-treated animals showed normal memory while rapamycin- and anisomycin-treated animals both showed significantly reduced memory (Fig. 4; ANOVA: main effect of drug, F2,33 = 19.16, p = 0.000003; post hoc Tukey tests, veh vs. rap, p = 0.000001, veh vs. aniso, p = 0.032, aniso vs. rap, p = 0.00048). Moreover, the rapamycin-treated mice exhibited significantly less contextual fear memory than anisomycin-treated mice in contrast to results seen 7 days after post-reactivation injection (see Fig. 3a). Thus, rapamycin’s effects on reconsolidation of a fear memory are long-lasting and ultimately of greater magnitude than those of anisomycin.

Figure 4. The effect of systemic rapamycin after reactivation is long-lasting and stronger than anisomycin.

Post-reactivation injection of rapamycin or anisomycin following a single memory reactivation significantly reduced subsequent recall of a fear memory 21 days later in the absence of drug (probe) (ANOVA: main effect of drug, F2,33 = 19.16, p = 0.000003; post hoc Tukey tests, veh vs. rap, p = 0.000001, veh vs. aniso, p = 0.032, aniso vs. rap, p = 0.00048). There was no difference between groups during training or reactivation (not shown, p > 0.05 for both).

The effects of rapamycin on traumatic memory recall and consolidation are not caused by nonspecific alterations in behavior but are rather a selective effect of rapamycin on fear memory processes. Acute administration of 40 mg/kg rapamycin, a dose that impairs fear memory reconsolidation and consolidation, does not alter locomotor activity (Fig. 5a, F1,22 = 1.36, p = 0.26) or anxiety-like behavior as measured as time spent in the light in the dark/light box (Fig. 5b, p = 0.48) and time in the open arms of the elevated plus maze (Fig. 5c, p = 0.71). Because rapamycin given prior to training reduced subsequent recall 24 h later, we tested foot shock sensitivity. Rapamycin-treated animals exhibited normal flinch and vocalization and jump response thresholds (Fig. 5d, flinch, p = 0.72, vocalizations, p = 0.46, jump, p =0.48). These control data further support a selective effect of rapamycin on fear memory consolidation and reconsolidation.

Figure 5. Systemic rapamycin does not alter activity or anxiety-like behavior.

a, Rapamycin-treated mice exhibited normal locomotor activity as measured 2 h in the locomotor apparatus (ANOVA: F1,22 = 1.36, p = 0.26). b, Anxiety-like behavior in the rapamycin-treated mice did not differ from vehicle controls as measured by time spent in the light side of the dark/light box (p = 0.48) or number of entries into the light side (not shown, p = 0.91). Legend in b applies to Panels c–d. c, There was no difference in time spent in the open arms in the elevated plus maze in rapamycin-treated mice (p = 0.71) or number of open arm entries (not shown, p = 0.93). d, Shock threshold to elicit flinching, vocalizing, and jumping was normal in rapamycin-treated mice (p = 0.72, p = 0.46, p = 0.48, respectively).

Discussion

Systemic administration of the FDA-approved drug rapamycin, a selective inhibitor of mTOR, immediately following memory reactivation inhibits reconsolidation of contextual fear conditioning. These results implicate mTOR-mediated regulation of protein translation in the mechanism of traumatic memory reconsolidation. Importantly, our findings clearly distinguish between an effect of rapamycin on reconsolidation rather than on extinction. Indeed, the effect of rapamycin is similar to, although stronger than, that of anisomycin, a drug that empirically defines reconsolidation (Debiec and Ledoux, 2004; Nader et al., 2000a; Nader, Schafe, and LeDoux, 2000b; Sara, 2000). Furthermore, the effect of rapamycin is not reversed by a reminder shock known to overcome effects of both standard extinction and extinction augmented pharmacologically (Cai et al, 2006). Blocking reconsolidation of a reactivated contextual fear memory may have particular therapeutic relevance for the treatment of acquired anxiety disorders such as PTSD.

In support of our results indicating an effect of rapamycin on fear memory reconsolidation, Parsons et al (2006) recently showed that a post-reactivation injection of rapamycin directly into the amygdala blocked subsequent recall of auditory cue fear conditioning. Unfortunately, no data on the requirement for memory reactivation, duration, responsiveness to reminder shock, or comparison to anisomycin were provided in this study, making the interpretation of a reconsolidation effect tenuous. Thus, our study is the first to definitively demonstrate that systemic inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin following a single traumatic memory reactivation inhibits reconsolidation of fear conditioning in a lasting manner. Furthermore, we have expanded this reconsolidation effect from auditory fear conditioning to contextual fear conditioning and provided evidence of systemic efficacy at a dose that does not appear to cause noticeable effects on pain sensitivity, anxiety, or locomotor activity.

Mice given anisomycin after reactivation showed reduced memory lasting at least 21 days. This is in direct contrast to Lattal and Abel (2004) which showed that anisomycin, when given after reactivation, had no effect on contextual fear memory tested 21 days later. This is likely due to the fact that Lattal and Abel (2004) used a much lower concentration of anisomycin (50 mg/kg vs. 150 mg/kg in the present study)(Lattal and Abel, 2004).

Interestingly, a single systemic rapamycin injection paired with memory reactivation led to a greater reduction in fear memory compared to anisomycin, measured 21 days after reactivation. This was particularly surprising as there was no difference between anisomycin and rapamycin treated groups measured 7 days after reactivation. It appears that the effects of rapamycin on memory reconsolidation may be longer lasting than those of anisomycin or at least of greater initial strength. These findings imply that rapamycin may act on a critical subset of mTOR regulated mRNAs important for reconsolidation of fear memory.

Recent studies have examined the effects of rapamycin on acquisition and consolidation of traumatic memory with inconsistent results. Bekinschtein and colleagues demonstrated that an intra-hippocampal infusion of rapamycin before training blocks long-term (24 h) inhibitory avoidance memory. Since memory tested 3 h after training was normal, they concluded that rapamycin hinders consolidation, not acquisition, of a fear memory (Bekinschtein et al., 2007). In additional experiments, however, they showed that a post-training infusion of rapamycin does not affect subsequent long-term memory, which does not directly support an effect on consolidation. On the other hand, Parsons et al., (2006) showed that a post-training intra-amygdala infusion of rapamycin does indeed inhibit consolidation of fear memory (Parsons et al., 2006). Of course, one potential explanation for the difference in results is that rapamycin was infused in different brain regions in each study and furthermore, different types of learning were studied. Our studies support the interpretation that rapamycin is indeed acting on the consolidation phase of contextual fear conditioning. Specifically, injection of rapamycin after training blocked subsequent memory recall tested 24 h later without affecting immediate short-term memory.

Clinically, pharmacologic interventions that decrease the strength of an established fear memory are of great potential benefit. Our data suggest that systemic inhibition of the mTOR pathway with rapamycin, a member of a class of mTOR inhibitors already in clinical use, may be used in concert with therapeutic reactivation of a traumatic memory for the treatment of PTSD and perhaps other acquired anxiety disorders. Importantly, we also show that rapamycin may be useful in inhibiting fear memories both immediately after acquisition (during consolidation) and after reactivation (during reconsolidation), providing two potential windows of opportunity for therapeutic prevention or intervention.

In conclusion, our findings implicate regulation of mRNA translation by mTOR in reconsolidation of conditioned fear memory. Consistent with Parsons et al, systemic rapamycin also inhibits consolidation of contextual fear memory (Parsons et al., 2006). In addition, we show that a systemic injection of rapamycin following a single traumatic memory reactivation blocks subsequent memory recall in a lasting manner. These studies provide a model for a therapeutic approach in the treatment of pathological emotional memories.

Acknowledgements

This work was generously supported by the Blue Gator Foundation (C.M.P.), NIMH (C.M.P.) and the UT Dallas/UT Southwestern Green Fellows Program and SURF Program at UT Southwestern (M.K.). C.M.P. & J.B. conceived and designed the experiments; M.K. carried them out with input and close supervision from J.B. & C.M.P.; M.K., J.B., & C.M.P. performed statistical analysis and created figures; J.B. wrote the manuscript with input from C.M.P. and M.K.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abel T, Lattal KM. Molecular mechanisms of memory acquisition, consolidation and retrieval. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:180–187. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekinschtein P, Katche C, Slipczuk LN, Igaz LM, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Medina JH. mTOR signaling in the hippocampus is necessary for memory formation. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtchouladze R, Abel T, Berman N, Gordon R, Lapidus K, Kandel ER. Different training procedures recruit either one or two critical periods for contextual memory consolidation, each of which requires protein synthesis and PKA. Learn Mem. 1998;5:365–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context, time, and memory retrieval in the interference paradigms of Pavlovian learning. Psychol Bull. 1993;114:80–99. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W, Blundell J, Han J, Greene RW, Powell CM. Post-reactivation Glucocorticoids Impair Recall of Established Fear Memory. J. Neuroscience. 2006;26:9560–9566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2397-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadio A, Martin KC, Giustetto M, Zhu H, Chen M, Bartsch D, Bailey CH, Kandel ER. A transient, neuron-wide form of CREB-mediated long-term facilitation can be stabilized at specific synapses by local protein synthesis. Cell. 1999;99:221–237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis HP, Squire LR. Protein synthesis and memory: a review. Psychol Bull. 1984;96:518–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debiec J, Ledoux JE. Disruption of reconsolidation but not consolidation of auditory fear conditioning by noradrenergic blockade in the amygdala. Neuroscience. 2004;129:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y. The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:51–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvarci S, Nader K. Characterization of fear memory reconsolidation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9269–9275. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2971-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexner LB, Flexner JB, De La Haba G, Roberts RB. Loss of memory as related to inhibition of cerebral protein synthesis. J Neurochem. 1965;12:535–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1965.tb04246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal KM, Abel T. Behavioral impairments caused by injections of the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin after contextual retrieval reverse with time. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4667–4672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306546101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Everitt BJ, Thomas KL. Independent cellular processes for hippocampal memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Science. 2004;304:839–843. doi: 10.1126/science.1095760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Memory--a century of consolidation. Science. 2000;287:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Davis M. Behavioral and neural analysis of extinction. Neuron. 2002;36:567–584. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader K, Schafe GE, Le Doux JE. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature. 2000a;406:722–726. doi: 10.1038/35021052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader K, Schafe GE, LeDoux JE. The labile nature of consolidation theory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000b;1:216–219. doi: 10.1038/35044580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons RG, Gafford GM, Helmstetter FJ. Translational control via the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway is critical for the formation and stability of long-term fear memory in amygdala neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12977–12983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4209-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedreira ME, Maldonado H. Protein synthesis subserves reconsolidation or extinction depending on reminder duration. Neuron. 2003;38:863–869. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell CM, Schoch S, Monteggia L, Barrot M, Matos MF, Feldmann N, Sudhof TC, Nestler EJ. The presynaptic active zone protein RIM1alpha is critical for normal learning and memory. Neuron. 2004;42:143–153. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00146-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybyslawski J, Sara SJ. Reconsolidation of memory after its reactivation. Behav Brain Res. 1997;84:241–246. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raught B, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N. The target of rapamycin (TOR) proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7037–7044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121145898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara SJ. Retrieval and reconsolidation: toward a neurobiology of remembering. Learn Mem. 2000;7:73–84. doi: 10.1101/lm.7.2.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider AM, Sherman W. Amnesia: a function of the temporal relation of footshock to electroconvulsive shock. Science. 1968;159:219–221. doi: 10.1126/science.159.3811.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW, Masushige S, Silva AJ, Kida S. Memory reconsolidation and extinction have distinct temporal and biochemical signatures. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4787–4795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei N, Inamura N, Kawamura M, Namba H, Hara K, Yonezawa K, Nawa H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent local activation of translation machinery and protein synthesis in neuronal dendrites. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9760–9769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei N, Kawamura M, Hara K, Yonezawa K, Nawa H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances neuronal translation by activating multiple initiation processes: comparison with the effects of insulin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42818–42825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SJ, Reis G, Kang H, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Schuman EM. A rapamycin-sensitive signaling pathway contributes to long-term synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:467–472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012605299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronel S, Alberini CM. Persistent disruption of a traumatic memory by postretrieval inactivation of glucocorticoid receptors in the amygdala. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]