Abstract

Purpose

This study was to examine functional loads of the tongue on its surrunding bones and how tongue volume reduction affects these loads.

Materials and Methods

Masticatory bone strains and pressures on facial bones directly contacted by the tongue were measured in twelve 12-week-old Yucantan minipigs (6 slibing pairs). One of a sibling pair received surgery to reduce the tongue volume by 23–25% (reduction group), the other had identical tongue incisions without tissue removal (sham group). Rosette strain gauges were bonded to the palatal surface of premaxilla (PM), the lingual surface of mandibular alveolar bones between the 2nd and 3rd decidious incisors (MI) and below the 3rd decidious molar (MM). Single-element stain gauges were placed across the palatal surface of premaxillary stuture (PMS) and the lingual surface of mandibular symphysis (MSP). Pressure tranducers were placed on the hard palatal surface of maxillary (PAL) and the lingual surface of mandible (MAN) posterior to the deciduous canine. Animals were allowed to feed unrestrainedly after surgery and device placement. Data from bone strain, pressure and electromyographic activity (EMG) of bilateral masseter muscles were recorded during natural mastication (pig chow).

Results

In sham animals, principal bone surface strains were less than 100με in all measures. Principal strains showed larger compressive than tensile strains at the PM, and larger tensile than compressive strains at the MI and MM. Tensile strains at the MM were significantly larger than that at the PM (p < 0.01). Strains were tensile and compresive at the PMS and MPS, respectively, with sigificantly higher magnitude (> 100με) at the PMS (p < 0.05). Pressures ranged 2.12–8.04 kPa with the larger readings at the MSP than the PAL (p < 0.05). Tongue volume reduction did not affect strain polarity at any site, but did diminish principal strain magnitudes, significnatly at the MI (p < 0.05). At the PM and MI, the principal tensile orientation was significantly altered from the latero-anterior to latero-posterior direction (p < 0.05–0.001). Strains at the MM and MSP showed little change. Compared to sham animals, tensile strain at the PMS and pressures at the PAL and MAN were decreased 50% or more(p < 0.01).

Conclusions

These results suggest that 1) the tongue produces larger functional loads (strains and pressures) on mandibular lingual surfaces than maxillary/premaxillary palatal surfaces; 2) tongue volume reduction decreases these loads, specifically those in the anterior mouth; 3) masticatory loads produced by the tongue on the lingual mandibular and palatal maxillary/premaxillary surfaces are much smaller than those produced by masticatory muscles on the dorsal surfaces of these bones and TMJ structures.

Keywords: Tongue, volume reduction, strain, pressure, pig

Introduction

In the craniofacial region, the largest forces on bone are generated intermittently during mastication.1 The tongue is thought to exert weaker but more frequent forces in function, which may impact surrounding hard tissue more than the larger muscles of mastication.2,3 Previous studies have found more continuous “resting” activity” in the tongue than the jaw elevators. 4 During chewing intrinsic tongue muscle activity is higher than the jaw elevators and extrinsic tongue muscles.4,5 A classical equilibrium theory assumes that pressure from the tongue is critical in determining teeth position and that resting pressure is more influential than functional pressure, such as mastication.3,6–8 In vivo functional loading data caused by the tongue on surrounding structures are extremely limited. To our knowledge, no study has directly measured the functional loading environment on osseous tissues surrounding the tongue, and tongue biomechanics to produce these loads are not well understood.

Tongue volume (size) and position are critical factors in tongue biomechanics. In humans the tongue reaches its approximate adult size by 8 years of age.9 There is a long-standing controversy whether the tongue adapts to fill an existing space or actively molds surrounding tissues.10–12 Numerous clinical studies have claimed that the tongue volume influences not only the position of the dentition,1,13–15 but also mandibular arch size and posture16,17 maxillary expansion, 18 vertical height of face19 and combined horizontal and vertical location of chin and symphysis.20 Others have rejected a role for tongue volume in mandibular prognathism and cranial size.20,21 Unfortunately, it is unknown whether and how tongue volume changes affect functional loading on its surrounding osseous tissues.

Therefore, the present study is designed to assess: 1) loading patterns and magnitudes (strains and pressures) that the tongue produces on its surrounding osseous tissues during mastication; and 2) what occurs when tongue volume is reduced. We hypothesized that normal tongue creates pressures and bending strains on its surrounding osseous tissues during mastication, and that these strains and pressures are reduced and the strain orientations are altered by tongue volume reduction.

Materials and Methods

ANIMALS

Twelve 12-week Yucatan miniature pigs (6 slibing pairs of each gender) were used. For acclimation of pigs to laboratory and experimental environment, daily training and handling were performed daily for 3–5 days, and 24-hours starvation was given before the experimental day. The housing, care and experimental protocol were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Washington.

TONGUE SURGERY

One of a slibing pair received tongue volume reduction surgery (reduction group), and the other had the same incisions but no tissue was removed (sham group). The surgery was perfomed under nostril-mask anesthesia using isoflurane and nitrous oxide, and a mouth opener was inserted to keep the gape at 35–40 mm and the tongue was pulled forward to expose the circumvallate papillae.

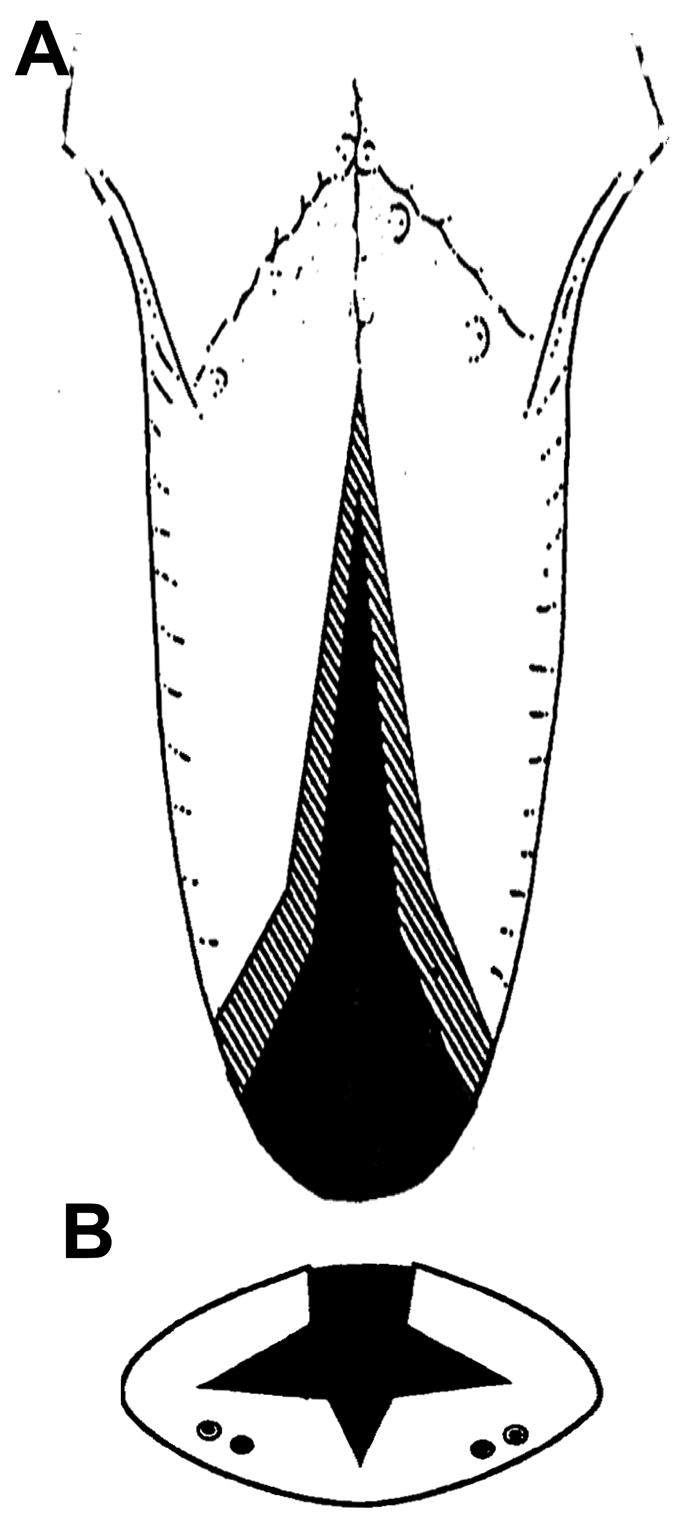

Following the method intruduced by Davalbhakta et al,22 the tongue reduction surgery began at making the apex of the incisions at the circumvallate papillae after a local infiltration of lidocaine HCI 0.5% and epinephrine 1:200,000 solution (3–5ml) by using an electrosurgical catery unit (SSE 2L, Valleylab, Boulder, CO). The bilateral incisions diverged to meet the lateral margin anteriorly. Cutting diathermy was used to undermine and create lateral muco-muscular flaps and excise of a conical wedge (above the tongue neurovascular bundles) from the central tongue. The tongue muscular tissue removed uniformly reduced tongue volume in three dimensions (Fig. 1A and B). The estimated amount of the reduction was 20–25 % of the original volume. After hemostasis, the incision was closed in layers with absorbable sutures (Vicryl 4.0). The removed tongue tissue was preserved in a 50% alcoholic solution, and its volume was measured by an overflow method. Its weight and linear dimensions were also measured. For the sham animals, only the same incisions were made and sutures were placed.

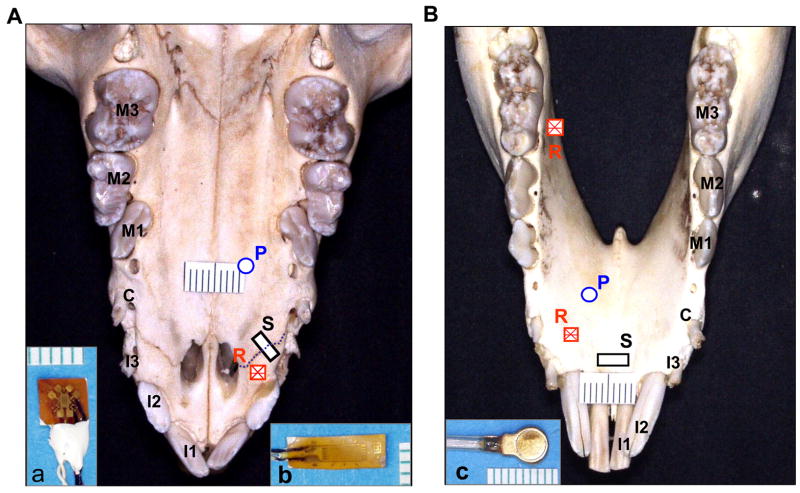

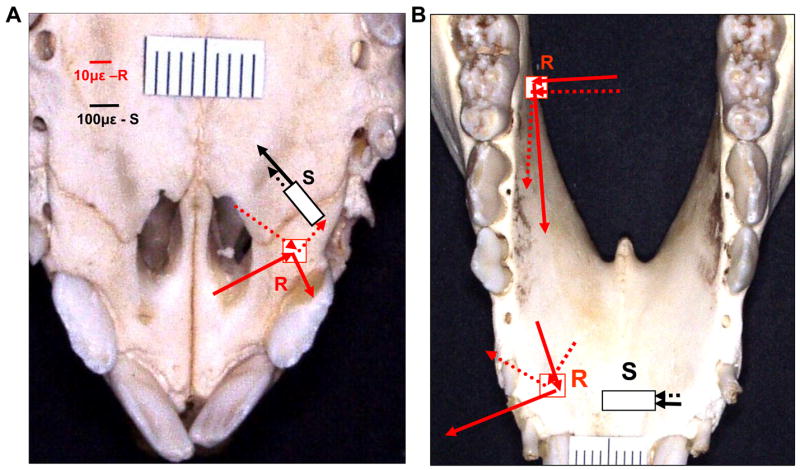

Figure 1.

Locations of strain gauges and pressure transucers. A: Palatal view of maxillae and premaxillae. B: Lingual veiw of mandible. R: stacked rosette strain gauge (inset a); S: single-element strain gauge (inset b); P: pressure transducer (inset c). I1-3: the 1st, 2nd and 3rd incisors; C: canine; M1-3: the 1st, 2nd and 3rd decicuous molars. Dotted line in A indicate premaxillary suture.

DEVICE INSTALLATIONS

After tongue surgery and still under anesthesia, insulated 45° stacked rosette strain gauges (SK-06-030WR-120, Vishay Micro-Measurement Group, Raleigh, NC) were glued on the right palatal surface of the premaxilla (PM) and the lingual surfaces of mandibular alveolar bones between the second and third deciduous incisors (MI) and below the deciduous third molar (MM), 5–6mm distant to their alveolar ridges. Single element strain gauges (EP-08-125BT-120) were put across the right premaxillary suture (PMS) on the palatal surface and across the lingual surface of the mandibular symphysis, 6–8mm below the alveolar ridge of the central incisors (MSP, Fig. 2A and B). The preparation for strain gauge placement involved exposing the bone surfaces, followed by cauterizing, smoothing, neutralizing, and drying.23 The strain gauges were glued to the bones with cyanoacrylate glue, and the mucosa and periostea were replaced and sutured after verifying that gauges were operational. For the installation of a single-element gauge, a piece of Teflon tape was placed over the suture line before gluing so that only the bone parts were glued to the gauge tabs. The strain gauge outputs were calibrated so that 1.0 V of output was equal to 1000με at a bridge excitation of 2.0 V DC.

Figure 2.

Incision lines in dorsal (A) and cross-section (B) views for tongue surgery by the uniform reduction technique. Dots indicate th elocation of the neurovascular bunndles in the ventral area of the tongue.

Pressure transducers (P19F, Konigsberg Co, Pasadena, CA) were first calibrated by immersing them in a sealed flask filled with 37–38°C water. Pressure within the flask was produced using a pressure bulb (Pressostabil, Speidel & Keller Inc., Germany). The transducers were connected via their compensation module to two DC preamplifiers (Model DA100C, Biopac Systems Inc., Santa Barbara, CA). Voltage output and pressure from 0 to 40Kpa within the flask were measured simultaneously. The linear relationships were confirmed (r2 = 0.98–0.99). The calibration further confirmed that the transducers cannot sense pressure in a vacuum environment such as negative pressure.

A 5 mm incision along the lateral border of the palatal mucosa distal to the right canine was made and a periosteal elevator was inserted to create a space for the transducer commendation. The first pressure transducer was placed underneath the palatal raphé 10mm distant to the alveolar ridge (PAL). The second pressure transducer was similarly placed underneath the mucosa of mandibular alveolar process between the canine and the first deciduous molar 8–10mm distant to their alveolar ridges (MAN) (Fig. 2A and B). Incisions were sutured after the placements. All of pressure transducer and strain gauge lead wires were sutured to adjacent tissues for stress relief and brought out of the mouth through the diastema between the third incisor and canine.

EMG electrodes (0.05mm nickel-chromium wire, 1mm bared tip and 2mm separation between wire tips) were inserted into both masseters, right digastricus, genioglossus, superior and inferior longitudinalis and verticalis/transverses by 25G hypodermic needles. The accuracy of electrode sites were evaluated by back stimulation, and were further confirmed through post-mortem dissection 24. Four fluorescent markers were glued on the skin of the upper and lower lips for digital videotaping of jaw movements. The methods for placements of EMG electrode and jaw movement markers have been published elsewhere.5,25 All leads were secured to a collar where they connected to the appropriate machinery (strain conditioner/amplifiers, DC amplifiers and EMG amplifiers). A local anesthetic (2% procaine hydrochloride) was infiltrated into all incisions and an analgesic (Ketorolac, 1mg/Kg) was injected intramuscularly.

Regular food (pig chow) was offered after pigs had completely emerged from anesthesia. This natural and unrestrained feeding was recorded for about 15–20 minutes via strain gauges, pressure transducers and EMG electrodes, and lateral and frontal video of jaw/head movements. All mechanical (strains and pressures) and EMG signals were digitized by AcqKnowledge (Ver. 3.7.3, 16-channel Analog/Digital conversion hardware and software, Biopac Inc. CA) simultaneously at a sampling rate of 500 Hz. Jaw movement was captured using a digital video camera (60 frame/s, Sony Co. Tokyo, Japan) and synchronized with bilateral masseter EMG signals through an Event &Video Control and Analog to Digital Interface (Peak Performance Technologies Inc. Centennial, CO).

DATA PROCESSING AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

After digital filtering (bandpass of 60–250 Hz for EMG and lowpass of 30 Hz for strain and pressure), signals from 5–10 consecutive chewing cycles from each pig were selected for analysis. The chewing side was identified by looking at the timing and amplitude differences between masseters, i.e., the higher amplitude and/or delayed onset were considered as an ipsilateral side.23,26 Attention was paid to the rhythm of jaw movements and regularity of masseter activity bursts (constant pattern) in order to exclude any possible transport and swallowing cycles. Ingestion cycles were excluded by o-line marking through direct visualization.5 Only consecutive and rhythmic jaw movement cycles (> 4) with stereotyped EMG activity of jaw and tongue muscles were selected for the study.

The digitized three-element rosette strain signals were analyzed using the combination of AcqKnowledge III (Ver. 2.7.3., Biopac) and a custom-made Excel macro. After pasting data points of baseline and strain production curve to Excel, the macro automatically calculated principal tensile (positive) and compressive (negative) strains, shear strains (sum of absolute values of principal strains), and the orientation of tensile strain relative to midline or occlusal plane, by using the standard formulae provided by the manufacturer, 27 and by subtracting baseline values from peak values for each chewing cycle. Signals from single-element strains were calculated directly by subtracting baseline values from peak values for each chewing cycle. Pressure changes were calculated according to the regression equation determined from calibration data.

SPSS (Version 11.0) for Windows was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistic was calculated for means, standard deviations (SD) and ranges of strain magnitudes, strain orientations and pressure values. One-way ANOVA were used to compare strain magnitudes and orientation in three rosette gauge sites followed by Tukey post-hoc tests for pair-wise comparisons. Non-paired t-test was performed for evaluate differences between sham and reduction groups, between working and balancing sides at each gauge or pressure site, and between two pressure transducers at each side. The significant level was set as p < 0.05.

Results

GENERAL BEHAVIORS

The animals tolerated the procedures (tongue surgery and device implanation) well. Five to ten minutes after emerging from anesthesia, the animals could usually stand and eat vigorously. studies on normal pig mastication.23,25,28 Reduction animals often used the mandible, instead of the tongue, to intake food up into the mouth (ingestion), and their head movement was increased during chewing compared to sham animals. Not all devices were operational during recording in some animals. Successfully completed recordings from strain gauges and pressure transducers are summarized in Table 1.

As documented in the previous studies,5,23,25,28, during mastication pigs alternate the working side and use both sides equally during sequence of consecutive chewing. The chewing side is easily identified by looking at the timing and amplitude differences between bilateral masseter muscles, i.e., the higher amplitude and/or delayed onset were considered as an working (ipsilateral) side23,26. The detailed comparison of EMGs of jaw and tongue muscles in relation to jaw movement phases in sham and reduction groups with those in normal control animals5 will be reported separately.

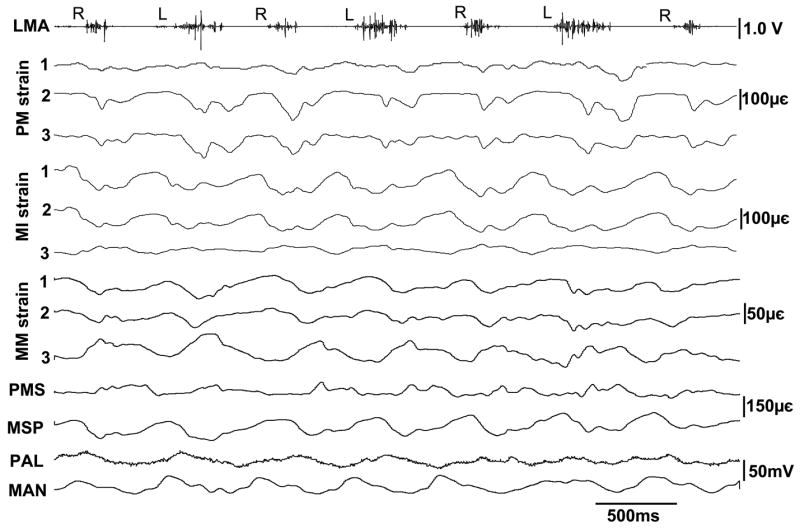

Fig. 3 illustrated a typical recording from 3 rosette and 2 single-element strain gauges, and 2 pressure transducers. Both strains and pressures occurred immediately following the masseter activation. It must be noted that for both strains and pressures, their baselines were unidentifiable during chewing. Therefore, only dynamic changes in bone strains and pressures (difference between peak and baseline for each chewing cycle) were analyzed, not resting values.

Figure 3.

Raw tracings of masseter EMG, bone strains and pressures. PM: rosette strains at the right premaxillary palatal surface, MI: rosette strains of the right mandibular alveolar lingual surface at the location between the 2nd and 3rd incisors; MM: rosette strains of the right mandibular alveolar lingual surface below the 3rd deciduous molar; PMS: single-element strain at the right premaxillary suture of palatal side; MSP: single-element strain of the mandibular alveolar lingual surface at the symphysis; PAL: pressure at the right palatal process posterior to the canine; MAN: pressure of the mandibualr lingual surface between the right canine and 1st deciduous molar. The three elements of each rosette gauge correspond to 1, 2, 3. R and L indicate working side of mastication.

BONE SURFACE PRINCIPAL STRAINS

Bone surface strain values and orientations at the PM, MI and MM are summarized in Table 2. Principal tensile and compressive strains were below 100με in most of measures. Strains were greater by compression at the PM, and by tension at the MI and MM. The magnitudes of the two mandibular tensile strains (MI and MM) were larger than that at the PM, significantly at the MM on both working and balancing sides (p < 0.05). Tensile strain orientations were distinct in each gauge site. The angle at the PM was acute to the midline anteriorly, while that at the MI was nearly perpendicular to the midline. The angle at the MM was about 50° above the occlusal plane (Fig. 4A and B). There were no significant differences in strain patterns (tension- or compression- dominant), magnitudes and orientations between working and balancing sides (Table 2).

Table 2.

Peak principal bone strains (Mean ± SD, in με) during mastication

| Working side

|

Balancing side

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Shear | Direc | Max | Min | Shear | Direc | |

| Premaxilla (PM) | ||||||||

| Sham | 30.3 ± 30.6 | −45.1 ± 52.9 | 75.4 ± 81.8 | 27.4 ± 6.4 | 27.3 ± 20.7 | −37.9 ± 40.5 | 63.5 ± 60.5 | 29.1 ± 7.2 |

| Reduction | 28.7 ± 20.0 | −34.6 ± 42.1 | 62.4 ± 58.9 | 151.8 ± 35.0*** | 19.9 ± 15.3 | −26.3 ± 28.3 | 46.2 ± 42.9 | 159.2 ± 40.6*** |

| Mandible-Incisor (MI) | ||||||||

| Sham | 68.3 ± 45.2 | −37.4 ± 34.2 | 105.7 ± 71.5 | 79.2 ± 34.1 | 64.9 ± 45.5 | −31.5 ± 25.5 | 96.5 ± 67.0 | 87.9 ± 41.7 |

| Reduction | 46.9 ± 53.7 | −30.0 ± 18.4 | 76.9 ± 64.2 | 126.7 ± 35.3** | 29.0 ± 23.6* | −17.3 ± 5.4* | 46.4 ± 22.5** | 119.1 ± 32.5* |

| Mandible-Molar (MM) | ||||||||

| Sham | 80.0 ± 57.8 | −40.5 ± 32.1 | 120.5 ± 67.6 | 50.1 ± 28.2 | 58.9 ± 30.3 | −44.3 ± 24.2 | 103.2 ± 50.2 | 54.3 ± 23.8 |

| Reduction | 69.6 ± 56.6 | −41.0 ± 40.3 | 110.6 ± 89.3 | 69.3 ± 24.7 | 48.4 ± 45.5 | −36.7 ± 45.7 | 85.2 ± 84.6 | 63.1 ± 29.6 |

|

| ||||||||

| ANOVA/Tukey | ||||||||

| Sham | MM > PM# | MM > PM# | MI > PM## | MM > PM# | MI > PM## | |||

| Reduction | PM > MM## | MM > PM# | PM > MI# | |||||

| MI > MM# | PM > MM## | |||||||

Max= tension; Min = compression; Shear = Max + Min (absolute value); Direc: direction of tension relative to the midline line (PM and MI) or the occlusal plane (MM, angle in degrees)

Independent t tests (Sham-Reduction comparison);

ANOVA/Tukey tests (Gauge-site comparision).

Figure 4.

Average principal strains for 3 rosette and 2 single-element gauge sites and in sham (solid-line arrows) and reduction (dotted-line arrows) animals (only working side illustrated. See Table 2 and Fig. 5 for all data and standard deviations). Arrows heading towar the guage site indicate compressive strain; arrows heard away from the guage site indicate tensile strain. In sham animals, the PM and MI showed larger compressive and tensile strains rexpectively, with the direction of tension latero-rostrally relative to the midline; the MM showed larger tensile strain, with the direction of tension oblique to the oclusal plane anterior-superiorly. The PMS and MSP showed tensile and compressive strains respectively. In reduction animals, strain magnitudes reduction and/or direction of tension change were seen at the PM, MI and PMS, and little change was seen at the MSP and MM. Note that different scales of strain magnitude for rosette and single-element gauges.

While the basic patterns of principal strains were unchanged, reduction group showed an overall decrease of strain magnitudes (18–48%) at all three sites (PM MI, and MM). A significan strain decrease was found at the MI on the balancing side (Table 2). Compared to other two anterior sites (PM and MI), strain magnitude decrease at the MM was smaller. In addition, tensile strain orientations were also significantly altered at the PM and MI from latero-anterior to latero-posterior in relation to the midline on both working and balancing sides (p < 0.05–0.001). However, little change in tensile strain orientation was found at the MM (Table 2 and Fig. 4).

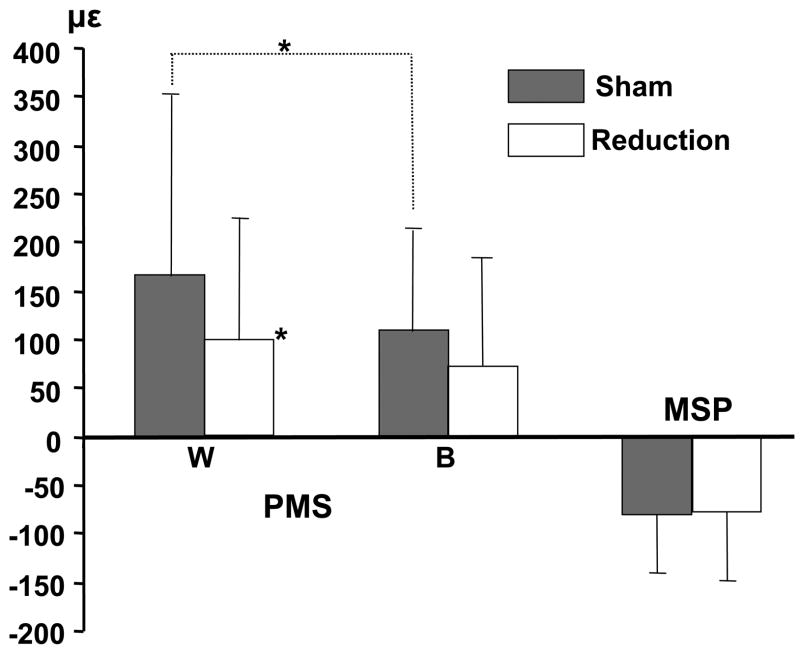

SUTURE AND SYMPHYSIS STRAINS

As the MSP was located in the midline, values from both sides were combined. Strain magnitude at the PMS and the MSP were generally larger than bone surface strain measured by rosette gauges (p < 0.05, Fig. 5), and the largest one (about 200με) was at the PMS. Tensile and compressive strains were identified at the PMS and MSP respectively. Tensile strain at the PMS was significantly larger on the working as compared to the balancing side. Tongue volume reduction did not alter the strain polarity, but diminished the tensile strain at the PMS, significantly on the working side (p < 0.05). Compressive strain at the MSP was unaffected (Fig. 4 and 5).

Figure 5.

Means and SD for single-element strains at the palatal side of right premaxillary suture (PMS) and lingual side of mandibualr symphysis (MSP). Positive and negative values represnt tensile and compressive strains respectively. W: working side; B: balancing side; no side idetification for the MSP. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01.

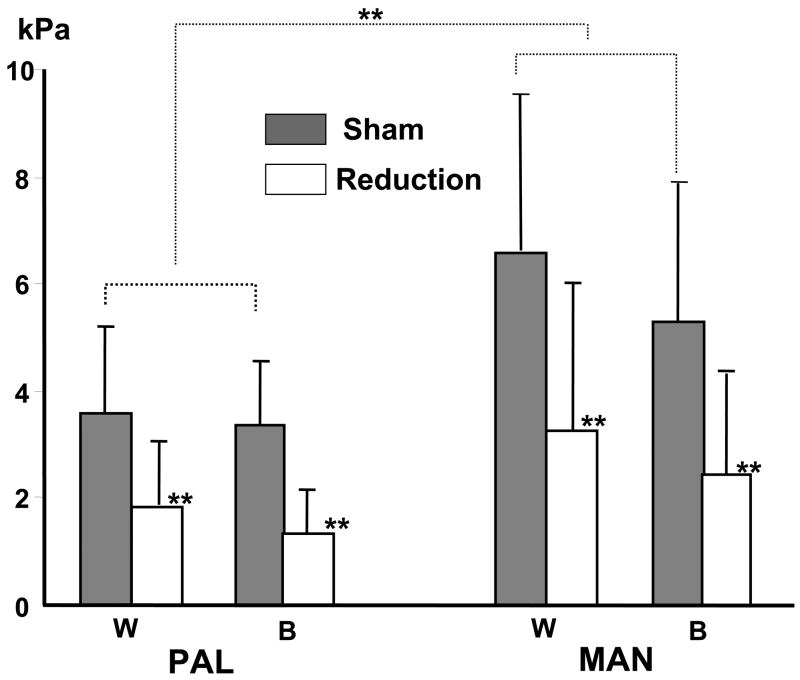

BONE SURFACE PRESSURES

Bone surface pressures ranged 2.12–8.04 kPa, and pressure at the MAN was significantly larger than that at the PAL on both working and balancing side (p < 0.05). No differences between sides were found. The tongue volume reduction significantly lowered pressure productions on both side (p < 0.01), particularly at the MAN where the pressure was reduced by 50% or more on both working and balancing sides, as compared to sham animals (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Means and SD for pressures at the palatal surface of right palatal process (PAL) and lingual surface of right mandibular alveolar bone between the right canine and 1st deciduous molar (MAN). W: working side; B: balancing side; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001.

Discussion

SELECTIONS OF ANIMAL MODEL AND TESTING SITES

Although there are certain anatomical differences between humans and pigs in craniofacial region, mostly contributing to longer dimensions of snout, oral cavity, anterior portion of the tongue and post-canine occlusal table, the pig has been considered to have the most resemblance of its masticatory apparatus to that of higher primates among non-primate mammals, such as jaw muscle locations and joint structures, tooth and dentition forms, and jaw movement pattern.29,30 The 12 –week Yacatan miniature pig was further chosen for the present study because 1) cranial morphology is uniform and presents with unique class III tendency of malocclusion (anterior crossbite), analogous to some human conditions for which tongue reduction might be considered; 2) active growth is ongoing as most of tongue reductions are performed in children; 3) moderate size (8–10Kg) facilitates handling and instrumentation, and has better tolerance to invasive surgery.

It has been universally accepted that local mechanical environment plays critical role in facial bone formation, growth and remodeling. The sites chosen for measure in the present study (premaxilla and its suture, mandibular symphysis and alveolar processes, and palatal process) all actively contribute to craniofacial growth. First, the premaxilla and its suture, and palatal process not only are active growth/remodeling fronts during midfacial development,31 but also affect decidous incisor size, position and upper dental arch form.32,33 Second, in the pig, growth of the alveolar process takes up approximately 60% and 20% of total mandibular height and length respectively, and growth of the condylar and posterior border of mandible makes about 80% contribution to the total ramus height and mandibular length.34 Clearly, direct loads on the alveolar process by the tongue and indirect loads on the condyle and the posterior border by tongue movement that pulls the mandible forward and downward are the most critical factors for mandibular growth, and possibly for maxillary growth as well. Third, although fused or partially fused, the mandibular symphysis is a key structure to transmit muscle force between the two sides, and to make muscle forces from both sides reliably available.35,36 Therefore, the in vivo load patterns obtained from the present study may shed light on the local mechanical environments of these actively growth sites of craniofacial complex during mastication.

MASTICATORY BONE STRAINS AND PRESSURES

Information about in vivo functional loads caused by the tongue is extremely scarce. Only the tongue pressures on teeth and hard palate have been measured.11,12,37,38 Apparently, these measurements provided no information about deformation (strain) on the osseous tissues surrounding the tongue. Therefore, data from the present study may fill this deficiency. It must be mentioned that although all measured loads were from sites which the tongue touches directly during mastication, tongue movement/deformation is not the sole source producing these loads. Possible contributions of masticatory and other coordinative muscles in the head and neck could not be excluded.

The bony rostrum of the pig is composed of maxillae, premaxillae and nasals, which are connected via sutures. A bone strain study on these structures in the pig indicates that strain at the premaxilla was tension-dominant with the magnitude around 100με, and the strain at its intervening suture was also tensile with much higher magnitude over 1000με.39 These measurements were all from the dorsal surfaces (outside) of these structures, thus cannot reflect the tongue’s role in producing these loads. The present study found that in sham animals, the strain at the palatal surface of the premaxilla was distinctively different from that at the dorsal surface, i. e., the strain was compression-dominant with much smaller maximum shear strain (Fig. 4). At premaxillary suture, the strain magnitude was approximately 10 times smaller than that at the dorsal surface, although the strain polarity (tensile) and side preference (significantly higher strain on the working side) were similar to that of the dorsal surface (Fig. 4 and Tab. 2).39 Furthermore, the orientation of peak tensile strain at the palatal surface of the premaxilla was almost diagonal to the midline. These strain features suggest that: 1) the tongue may generate most of these loads, not the masticatory muscles; 2) the premaxilla bends in a ventral direction; 3) the distortions at the dorsal and palatal sides of the premaxillary suture (both are tension) may stimulate osteogenesis along this entire interface. In addition, the similarity of strain pattern and magnitude between the working and balancing sides at the palatal surface of premaxilla are consistent with strains measured at the dorsal surface of the maxilla in the pig.40

Bone strains at the lingual surfaces of alveolar process and the symphysis of mandible have not been reported. The present study revealed that both anterior and posterior mandibular alveolar processes (MI and MM) underwent tension-dominant principal strain with higher magnitudes than that of premaxilla (PM). The peak tensile orientation at the incisor site (MI) was almost perpendicular to the midline, indicating bending in the transverse plane. Unlike the premaxillary strains (PM) which showed distinctively different magnitudes at the dorsal and ventral (palatal) surfaces, the strains at the molar site (MM) exhibited similar magnitude on the lingual (this study) and buccal sides,23 although dominance of principal strains is opposite, i. e., tension at the lingual (Fig. 4) and compression at the buccal surfaces.23 In addition, the orientations of these principal strains at these two surfaces are comparable at the angle of 45° roughly to the axis of mandible (Fig. 4 and Tab. 2)23. These features further demonstrate that the rigid single structure of mandible undergoes both transverse bending and twisting during mastication as found in the previous studies.23,41,42

The fused symphysis experiences dorso-ventral shear due to the transferring of force from the balancing to chewing sides.36 A mathematical modeling predicted that stresses and strains should be similar in human and pig symphysis.43 Compared to the tensile symphyseal strain on the labial surface,42 the lingual symphyseal strain (MSP) was compressive, and the magnitude was as much as 10 times smaller (Fig. 5). Combining the strain patterns at the alveolar process of the lingual and buccal surfaces, it can be speculated that the lower border of mandible is everted during mastication.

In humans, tongue resting pressures are negative at upper and lower incisors and upper molars (0–2 g/cm2). The maximal tongue pressure on teeth is produced by swallowing (200–350 g/cm2), while only 50–150 g/cm2 is elicited by chewing.12 The tongue pressures at various sites of the hard palate range between 0.8 to 17.1 kPa in young humans during mastication, and the smallest pressure is in the posterior midline.44 While rest pressures were not measured in the present study, masticatory pressures on both palate and mandibular body in sham animals are comparable with those in humans. Furthermore, the tongue produced significantly higher pressure on the mandibular lingual surface (MAN) than on the maxillary palatal process (PAL, Fig. 6). Similar to its bone surface strains, chewing side did not have significant influence on these pressure productions.

CONSEQUENCES OF TONGUE VOLUME REDUCTION

It has been suggested that tongue volume changes induce osteogenesis.45 As a muscular hydrostat organ, tongue volume forms its local mechanical environment.46 Little is known about how the change in tongue volume alters the functional loading on its surrounding osseous structures, and in turn affects bone growth and remodeling. By comparing tongue pressure on the teeth’s lingual surface before and after partial glossectomy, Frohlich et al concluded that the resting and swallowing pressures were decreased while chewing pressure was unchanged after the period of six to twelve months.11

For the first time, the present study addressed the issue how tongue volume reduction affects functional loading.. The results demonstrated that the volume reduction not only decreased overall magnitudes of bone surface and suture strains, but also strain orientations (Fig. 4). Because the volume reduction are usually performed on the anterior two thirds of the tongue, and this portion of the tongue is thought to produce greater forces and modulation than does the tongue base,47 the major changes in bone strains were found in the anterior mouth, which includes strains at the premaxillae (PM) and its suture (PMS), and strain (MI) and pressure (MSP) at anterior sites of the mandible (Fig. 4, 5 and 6). While no change was found in strain dominance (rosette gauges) and polarity (single-element gauges) at all sites, the volume reduction significantly altered the angles of principal tensile strains at the two anterior sites (PM and MI) from the latero-anterior to latero-posterior direction on both sides (Fig. 4 and Tab. 2), indicating these bony components are probably pulled posteriorly by the volume-reduced tongue.

Of 7 recording sites, 3 sites presented certain unique features in reduction animals. First, compared to sham animals, the influence of tongue volume reduction was relatively weak on the surface strain at the mandibular molar site (MM), both in strain magnitude and orientation. As mentioned above, this feature might be caused by 1) the posterior tongue, both the morphology and deformation, was less affected by the reduction surgery thus produced functional loads close to that in sham animals; and 2) in addition to the tongue, masticatory muscles may contribute significantly to strain production at this molar site, as the strain magnitudes at the lingual and buccal surfaces are closely comparable.23 Second, compared to mandibular pressure, the decrease of the palatal pressure was significantly less (about 65–70% vs 35–40%, Fig. 6). This difference could be explained: 1) higher loading magnitudes were found at the mandible than the maxilla/premaxilla for both bone surface strains and pressures in sham animals; 2) the palatal pressure transducer was located posterior to the mandibular one. Third, significant decrease of loading should be expected at the mandibular lingual symphysis (MSP) after tongue volume reduction, as this site is most anterior of all sites. However, no strain change was found at this site (Fig. 5). Compared to the symphyseal strain magnitude of the labial surface,42 the strain on the lingual surface is extremely low (20–160με). Thus, it could be speculated that this weak strain is produced passively by strong everting of the mandibular border via latero-superior pulling forces of masticatory muscles and jaw joint reaction force, rather than by the direct contact of the tongue.

In summary, for the first time, the present study reveals loading patterns and magnitudes (bone strains and pressures) on osseous tissues directly surrounding the tongue during mastication, and describes load changes after surgical tongue volume reduction. The results support the proposed hypothesis that normal tongue creates comparable pressures and weak bone strains on surrounding osseous tissues during mastication, and that these strains and pressures are reduced and the strain orientations are altered when the tongue volume is decreased. Further studies are underway to explore whether these effects on functional loads by tongue volume reduction are transient or long term, and how these effects influence craniofacial growth and occusal development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant no. R01DE15659 (to Z.J.L)

The authors would like to thank Drs. Mustafa Kayalioglu and Amir Seifi, and Ms. Xian-Qin Bai for help with experiments. Special thank goes to Dr. Sue Herring for her advice and comments.

List of Abbreviations

- EMG

Electromyography

- MAN

Pressure at the lingual surface of right mandibular alveolar process

- MI

Strain at the lingual surface of the right mandibular incisor alveolar process

- MM

Strain at the lingual surface of the right mandibular molar alveolar process

- MSP

Strain across the mandibular symphysis on the lingual surface

- PAL

Pressure at the right palatal process of maxilla

- PM

Strain at the palatal surface of the right premaxilla

- PMS

Strain across the right premaxillary suture on the palatal surface

References

- 1.Turner S, Nattrass C, Sandy JR. The role of soft tissues in the aetiology of malocclusion. Dent Update. 1997;24:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josell SD. Habits affecting dental and maxillofacial growth and development. Dent Clin North Am. 1995;39:851–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proffit WR. Equilibrium theory revisited: factors influencing position of the teeth. Angle Orthod. 1978;48:175–186. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1978)048<0175:ETRFIP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rikimaru H, Kikuchi M, Itoh M, Tashiro M, Watanabe M. Mapping energy metabolism in jaw and tongue muscles during chewing. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1849–1853. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800091501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayalioglu M, Shcherbatyy V, Liu ZJ. Role of Tongue Intrinsic and Extrinsic Muscles in Feeding: Electromyographic Study in Pigs. Arch Oral Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.01.004. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein S, Haack DC, Morris LY, Synder BB. On an equilibrium thoery of tooth position. Angle Orthod. 1963;33:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proffit WR. Muscle pressures and tooth position: North American whites and Australian aborigines. Angle Orthod. 1975;45:1–11. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1975)045<0001:MPATPN>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proffit WR, McGlone RE, Barrett MJ. Lip and tongue pressures related to dental arch and oral cavity size in Australian aborigines. J Dent Res. 1975;54:1161–1172. doi: 10.1177/00220345750540061101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Proffit WR, Mason RM. Myofunctional therapy for tongue-thrusting: background and recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 1975;90:403–411. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1975.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingervall B, Schmoker R. Effect of surgical reduction of the tongue on oral stereognosis, oral motor ability, and the rest position of the tongue and mandible. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;97:58–65. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(05)81710-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frohlich K, Ingervall B, Schmoker R. Influence of surgical tongue reduction on pressure from the tongue on the teeth. Angle Orthod. 1993;63:191–198. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1993)063<0191:IOSTRO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frohlich K, Thuer U, Ingervall B. Pressure from the tongue on the teeth in young adults. Angle Orthod. 1991;61:17–24. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1991)061<0017:PFTTOT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe AA, Takada K, Yamagata Y, Sakuda M. Dentoskeletal and tongue soft-tissue correlates: a cephalometric analysis of rest position. Am J Orthod. 1985;88:333–341. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(85)90133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen AM, Vig PS. A serial growth study of the tongue and intermaxillary space. Angle Orthod. 1976;46:332–337. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1976)046<0332:ASGSOT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vig PS, Cohen AM. The size of the tongue and the intermaxillary space. Angle Orthod. 1974;44:25–28. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1974)044<0025:TSOTTA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vig PS, Cohen AM. The size of the human tongue shadow in different mandibular postures. Br J Orthod. 1974;1:41–43. doi: 10.1179/bjo.1.2.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamari K, Shimizu K, Ichinose M, Nakata S, Takahama Y. Relationship between tongue volume and lower dental arch sizes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:453–458. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70085-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enlow DH. Handbbok of facial growth. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co.; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doual-Bisser A, Doual JM, Crocquet M. Hyoglossal balance and vertical morphogenesis of the face. Orthod Fr. 1989;60(Pt 2):527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoo E, Murakami S, Takada K, Fuchihata H, Sakuda M. Tongue volume in human female adults with mandibular prognathism. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1957–1962. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750120701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruff RM. Orthodontic treatment and tongue surgery in a class III open-bite malocclusion. A case report Angle Orthod. 1985;55:155–166. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1985)055<0155:OTATSI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davalbhakta A, Lamberty BG. Technique for uniform reduction of macroglossia. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:294–297. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu ZJ, Herring SW. Masticatory strains on osseous and ligamentous components of the temporomandibular joint in miniature pigs. J Orofac Pain. 2000;14:265–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu ZJ, Ikeda K, Harada S, Kasahara Y, Ito G. Functional properties of jaw and tongue muscles in rats fed a liquid diet after being weaned. J Dent Res. 1998;77:366–376. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770020501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu ZJ, Kayalioglu M, Shcherbatyy V, Seifi A. Tongue deformation, jaw movement and muscle activity during mastication in pigs. Arch Oral Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.10.024. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang X, Zhang G, Herring SW. Effects of oral sensory afferents on mastication in the miniature pig. J Dent Res. 1993;72:980–986. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720061401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Note M-MGT. Strain gauge rosette - Selection, application and data reduction. Tech Note. 1990;515:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu ZJ, Green JR, Moore CA, Herring SW. Time series analysis of jaw muscle contraction and tissue deformation during mastication in miniature pigs. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31:7–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herring SW. Mastication and maturity: a longitudinal study in pigs. J Dent Res. 1977;56:1377–1382. doi: 10.1177/00220345770560111701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herring SW. Animal models of temporomandibular disorders: how to choose. In: Sessle BJ, Bryant PS, Dionne RA, editors. Temporomandibular Disorders and Related Pain Conditions. Seattle: IASP Press; 1995. pp. 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barteczko K, Jacob M. A re-evaluation of the premaxillary bone in humans. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2004;207:417–437. doi: 10.1007/s00429-003-0366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Njio BJ, Kjaer I. The development and morphology of the incisive fissure and the transverse palatine suture in the human fetal palate. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1993;13:24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sejrsen B, Kjaer I, Jakobsen J. The human incisal suture and premaxillary area studied on archaeologic material. Acta Odontol Scand. 1993;51:143–151. doi: 10.3109/00016359309041160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson IB, Sarnat BG. Growth pattern of the pig mandible. A serial roentgenographic study using metallic implants. Am J Anat. 1955;96:37–64. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000960103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hylander WL. The functional significance of primate mandibular form. J Morphol. 1979;160:223–240. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beecher RM. Functional significance of the mandibular symphysis. J Morphol. 1979;159:117–130. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051590109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hori K, Ono T, Iwata H, Nokubi T, Kumakura I. Tongue pressure against hard palate during swallowing in post-stroke patients. Gerodontology. 2005;22:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2005.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thuer U, Sieber R, Ingervall B. Cheek and tongue pressures in the molar areas and the atmospheric pressure in the palatal vault in young adults. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21:299–309. doi: 10.1093/ejo/21.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rafferty KL, Herring SW, Marshall CD. Biomechanics of the rostrum and the role of facial sutures. J Morphol. 2003;257:33–44. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herring SW, Rafferty KL, Liu ZJ, Marshall CD. Jaw muscles and the skull in mammals: the biomechanics of mastication. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2001;131:207–219. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00472-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daegling DJ, Hylander WL. Occlusal forces and mandibular bone strain: is the primate jaw “overdesigned”? J Hum Evol. 1997;33:705–717. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1997.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herring SW, Rafferty KL, Liu ZJ, Sun Z. Primate Craniofacial Function and Biology; Developments in Primatology Series. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang F, Langenbach GE, Hannam AG, Herring SW. Mass properties of the pig mandible. J Dent Res. 2001;80:327–335. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hori K, Ono T, Nokubi T. Coordination of tongue pressure and jaw movement in mastication. J Dent Res. 2006;85:187–191. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fränkel F, Fränkel C. Orofacial orthopedics with the functional regulator. Basel: Karger; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kier WM, Smith KK. Tongues, tentacles and trunks: the biomechanics of movement in muscular-hydrostats. Zool J Linn Soc. 1985;83:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pouderoux P, Kahrilas PJ. Deglutitive tongue force modulation by volition, volume, and viscosity in humans. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1418–1426. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90690-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]