Abstract

Mixed-pathogen infections of vectors rarely are considered in the epidemiological literature, although they may occur in nature. A review of published reports shows that many Anopheles species are capable of carrying sporozoites of > 1 plasmodium species, of doing so simultaneously in field conditions, and of acquiring and transmitting these in experimental situations. Mixed-species infections in mosquito populations occur at frequencies greater than or equal to the product of the constituent species prevalences, whereas human populations have apparent mixed-species infections at frequencies less than or equal to their corresponding expected values. We present a model for the accumulation of parasite infections over the lifespan of a mosquito that explains this surplus of mixed-species infections. However, the expected frequencies of mixed infections on the basis of our model are greater than those found in nature, indicating that the sampling by mosquitoes of Plasmodium species from human malaria infections may not be random.

Keywords: Anopheles spp, Plasmodium spp, malaria transmission, parasite ecology

The Pioneering studies of parasite community dynamics have focused on helminths (e.g., Schad 1963, Kennedy 1975, Holmes 1983, Esch et al. 1990). Recently Dobson (1985, 1990) and Dobson and Roberts (1994) have stressed the role of species life-histories in structuring helminth communities and have extended the general ecological principle that as a constituent species becomes more aggregated in its distribution, the relative importance of interspecific competition declines in its population regulation. Although data on the aggregation of Plasmodium species in Anopheles is essentially anecdotal, its variability indicates that Plasmodium species interactions may warrant more concerted investigation.

In mixed-species malaria infections of humans, one of the constituent Plasmodium species typically dominates (e.g., Mayne and Young 1938, Molineaux and Grammicia 1980, Looareesuwan et al. 1987, Fox and Strickland 1989). Cohen (1973) analyzed the epidemiological literature and reported a general deficit of detectable mixed-species infections, associated this deficit with splenomegaly, and inferred an underlying heterologous immunity. Hence, the excess of mixed-species infections found during the Carlo project was unexpected, but it also was interpreted as representing species interactions of predominantly cooperative (Cohen and Singer 1979) or predominantly competitive (Molineaux and Grammicia 1980) character. Richie (1988) emphasized competitive interactions in an evolutionary context, suggesting that co-infections promote antigenic divergence, but also proposed a role for mutual facilitation in the ecological succession of Plasmodium species within a mammalian host.

Neither the interactions of pathogen species within vectors or the pathogen sampling processes embodied in human-vector contacts have received much attention in the infectious-disease literature. Most mathematical models of parasite-host interactions (e.g., Cohen and Singer 1979, Beck 1984, Bremermann and Thieme 1989, Anderson and May 1991) exclude the possibility that several pathogen species or strains can be transmitted (or cleared) simultaneously. Empirical studies show that in some Aedes species, coinfecting microfilariae can suppress P. gallinaceum Brumpt development (Albuquerque and Ham 1995), whereas coinfecting microfilariae or P. gallinaceum enhance arbovirus transmission (Turell et al. 1984, Paulson et al. 1992, Vaughan and Turell 1996). It also has been proposed that microfilariae and Plasmodium species retard the development of each other in Anopheles gambiae Giles s.l. (Muirhead-Thomson 1953), and that the high frequency of such coinfections in An. punctulatus Doenitz is balanced epidemiologically by increased mosquito mortality (Burkot et al. 1990).

If mixed-species Plasmodium infections of Anopheles have similar (or any other) effects, these and their epidemiological consequences apparently remain unexplored. In this article, we assemble evidence that many Anopheles species can carry and transmit >1 Plasmodium species simultaneously. The sparse data available indicate remarkable variability in the relationships of mixed-species Plasmodium prevalence in Anopheles to mixed-species prevalence in corresponding human populations and the prevalence expected under the hypothesis of species independence.

One important characteristic of the process by which mosquitoes sample pathogens is that they sample repeatedly over time, for instance every other day. Because vectors apparently do not clear pathogens once infected, the sampled pathogens accumulate over the lifespan of the mosquito. Therefore, we would expect that older mosquitoes would exhibit a higher frequency of multiple infections than either the prevalence of multiple infections in humans or the product of the prevalences of the individual species, the usual null statistical hypothesis. Younger mosquitoes would have a lower prevalence of multiple infections than older ones, so the overall prevalence of multiple infections in vectors depends on the lifespan and age distribution of the vector population. We present a simple model of the sampling and accumulation process that gives an indication of the degree to which the prevalence of multiple infections in the vector population might be increased.

Materials and Methods

The detection of mixed-species mosquito infections through microscopy is not possible (e.g., Shute and Maryon 1952), but it may be accomplished using enzyme immunoassays. We located our sources by consulting standard references (e.g., Wernsdorfer and McGregor 1988) and surveying recent English- and French-language journals in the Countway and Mayr Libraries at Harvard University. We used the G-test with the Williams correction (Sokal and Rohlf 1981) to analyze contingency tables of prevalence data.

For simplicity, in constructing a heuristic model we assumed that PA and PB, the prevalences of infectious gametocytes for 2 Plasmodium species in the human population, are constant (i.e., that the parasite populations in the human and mosquito populations are in joint equilibrium or are not dynamically linked). Other parameters we consider are the 2-d mosquito mortality (s), and duration of sporogonic cycle (D), Our units of time (t), correspond to an idealized 2-d gonotrophic cycle, typical for many tropical species in the subgenus Cellia.

Given the further assumptions that mosquitoes bite only humans and efficiently acquire infections from infectious gametocyte carriers, we note that (1 − Pj)t represents the probability that at age t a mosquito has not been infected with parasite species j, and 1 − (1 − Pi)t represents the probability that at age t a mosquito has been infected at least once with species i. We assume constant, continuous mortality in the mosquito, so e−sk represents the probability that a mosquito survives to age k.

We then express the probabilities that a mosquito of age D + t is infectious (no mosquitoes younger than D + 1 can be infectious) and sum over t and divide by the total number of mosquitoes to obtain the frequencies of mosquitoes that are infectious:

for species A and only species A, as

| (1) |

for species B and only species B, as

| (2) |

for neither species A nor species B, as

| (3) |

Therefore, the prevalence of mosquitoes simultaneously infectious for both species A and species B, is

| (4) |

The fraction of positives that is multiply infectious is VAB/(1 − V0).

We translated this model into a BASIC program to approximate and graph numerical solutions. The summations were truncated at t = 50 (100 d), because for the survivorship values of interest the probability of a mosquito surviving beyond this age is remote.

Results

At least 39 species of Anopheles are known to be capable of transmitting > 1 species of Plasmodium (Table 1). Individuals of at least 7 of these species have been detected carrying sporozoites of > 1 Plasmodium species in the field, and individuals of an additional 4 species simultaneously have transmitted 2 species in experimental settings.

Table 1.

Anopheles species known to be capable of transmitting >1 species of Plasmodium, singly or concurrently

| Anopheles | Single-species infections

|

Mixed-species infections

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAL | MAL | OVA | VIV | Refs | Refs (Field) | Refs (EXP) | |

| An. albimanus Wiedemann | x | x | x | Beach et al. 1992, Molineaux 1988, Olano et al. 1985 | |||

| An. amictus Edwards | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | ||||

| An. annularis van der Wulp | x | x | x | Amerasinghe et al. 1991 | |||

| An. annulipes Walker | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | ||||

| An. atroparvus Van Thiel | x | x | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | 28 FV | |

| An. balbacensis Baisis s.l. | x | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | |||

| An. bancrofti Giles | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | ||||

| An. culifacies Giles s.l. | x | x | Amerasinghe et al. 1991, Mendis et al. 1990 | 29 FV | |||

| An. darlingi Root | x | x | Klein et al. 1991a,b | ||||

| An. deaneorum Rosa-Freitas | x | x | Branquinho et al. 1993 | ||||

| An. dirus Peyton and Harrison | x | x | Baker et al. 1987, Gingrich et al. 1990, Harbach et al. 1987 | 27 FV | |||

| An. farauti Laveran | x | x | x | Burkot et al. 1987, Wirtz et al. 1987 | 19 FM/FV | ||

| An. fluviatilis James | x | x | 29 FV | ||||

| An. freeborni Aitken | x | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | |||

| An. funestus Giles | x | x | x | 5, 6, 30 FM/FO/MO/FMO | |||

| An. gambiae Giles s.l. | x | x | x | x | Collins & Roberts 1991 | 5, 6, 15, 30 FM/FO/MO/FMO | |

| An. koliensis Owen | x | x | Burkot et al. 1987, Wirtz et al. 1987 | ||||

| An. lindesayi pleccau Koidzumi | x | x | x | Lien 1991 | |||

| An. longirostis Brug | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | ||||

| An. ludlowae Theobald | x | x | x | Lien 1991 | |||

| An. maculatus Theobald | x | x | x | x | Lien 1991, Molineaux 1988 | 18 (F, M, V “mixed”) | |

| An. mediopunctatus Theobald | x | x | Klein et al. 1991a,b | ||||

| An. minimus Theobald | x | x | x | Gingrich et al. 1990, Harbach et al. 1987 | |||

| An. nigerrimus Giles | x | x | Baker et al. 1987 | ||||

| An. nili Theobald | x | x | Boudin et al. 1991 | ||||

| An. oswaldoi Peryassu | x | x | x | Branquinho et al. 1993, de Arruda et al. 1986 | |||

| An. peditaeniatus Leicester | x | x | Baker et al. 1987 | ||||

| An. punctipennis Say | x | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | |||

| An. punctulatus Doenitz | x | x | x | Burkot et al. 1987, Wirtz et al. 1987 | 2, 11, 12 FV | ||

| An. quadrimaculatus Say | x | x | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | 8 FV | |

| An. sacharovi Favre | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | ||||

| An. sinensis Wiedemann | x | x | x | Lien 1991 | |||

| An. splendidus Koidzumi | x | x | x | Lien 1991 | |||

| An stephensi Liston | x | x | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | 26 FV | |

| An. stipmaticus Skuse | x | x | Molineaux 1988 | ||||

| An. subpictus Grassi | x | x | x | Amerasinghe et al. 1991 | |||

| An. tessellatus Theobald | x | x | x | Gamage-Mendis et al. 1993, Lein 1991 | |||

| An. triannulatus Neiva and Pinto | x | x | Klein et al. 1991a,b | ||||

| An. vagus Donitz | x | x | Baker et al. 1987 | ||||

Refs, references; FAL or F, P. falciparum; MAL or M, P. malariae; OVA or O, P. ovale; VIV or V, P. vivax; FV, FM, FO, MO, or FMO, species in mixed infections; for field or experimental (EXP) studies. Beach et al. 1992; Collins & Roberts 1991; Klein et al, 1991a,b; Lien 1991; Olano et al, 1985 (for single-species infections) also involve experimental rather than field studies. Molineaux 1988 reviews microscopy-based studies. Boyd et al. 1937, Collins & Roberts 1991, Gamage-Mendis et al. 1993, Graves et al. 1988, Klein et al. 1991a,b, Lien 1991, Olano et al. 1985, Shute 1951 report results from microscopy; Amerasinghe et al. 1991, Anthony et al. 1992, Baker et al. 1987, Branquinho et al. 1993, Burkot et al. 1990, Burkot et al. 1992, Fontenille et al. 1992, Harbach et al. 1987. Mendis et al. 1990, Subbarao et al, 1992 from immunoassay; Beach et al. 1992, J. Beier et al. 1991, M. Beier et al 1988, Boudin et al. 1991, Burkot et al, 1987, de Arruda et al, 1986. Gingrich et al. 1990, Gordon et al. 1991, Ponnudurai et al. 1990, Rosenberg et al, 1990, Trape et al. 1994, Wirtz et al. 1987 from both. In nineteen of twenty references microscopy revealed salivary glands positive for sporozoites, but in de Arruda et al. 1986 only midguts positive for oocysts.

With few exceptions, the available frequency information about mixed Plasmodium species in the 7 Anopheles species applies only to positives (i.e., we have data on multiple- and single-species infections but not on overall prevalence). In 2 studies the frequency of mixed-species infections among mosquito positives was less than that among human positives, and in another 3 the converse was true (Table 2). Data from the remaining studies indicated that different circumstances in the same location might lead to either of these relationships, as might analyses conducted at different temporal and spatial scales.

Table 2.

Frequencies of mixed Plasmodium species in Anopheles species and in corresponding human populations

| Location | Plasmodium | Anopheles | Mixed as % of positives

|

Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquitoes | Humans | ||||

| Senegal | F, M, O | An. gambiae | 12 | 30 | Trape et al. 1994 |

| An. funestus | 17 | ||||

| Kenya | F, M, O | An. gambiae | 16 | 11 | M. Beier et al. 1988, Spencer et al. 1987 |

| An. funestus (both spp.) | 14 | ||||

| 3 | J. Beier et al. 1991 | ||||

| Madagascar | F, M, O, V | An. gambiae | 2 | 38 | Fontenille et al. 1992 |

| India | F, V | An. culifacies | 33 | 3 | Subbarao et al. 1992 |

| An. fluviatilis | 100 | ||||

| Thailand | F, V | An. dirus | 5 | 4 | Rosenberg et al. 1990a,b |

| 0 | 5 | ||||

| 4 | Gingrich et al. 1990 | ||||

| Malaysia | F, M, V | An. maculatus | 44 | 36 | Gordon et al. 1991 |

| New Guinea | F. M, O, V | An. punctulatus | 11 (FV) | 3 (2FV) | Anthony et al. 1992 |

| F, M, V | 1–9 (FV) | 4–16 (FV) | Burkot et al. 1987, 1990, 1992 | ||

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

The comparative figure for humans in Kenya, as cited by Beier et al. (1988), refers to a 1980–1983 study of 36 villages in the Saradidi region (Spencer et al. 1987); the entomological study by Beier et al. (1988) took place in 1986 in 2 of these villages, whereas that of Beier et al. (1991) took place in 1987–1988 in the same villages. The 2 complete sets of Thai figures (Rosenberg et al. 1990a, b) apply to the 1st and 2nd yr of a village study; in each year the prevalence of mixed-species infections in mosquitoes fit the hypothesis of the statistical independence of the species, whereas that in humans was less than half the expected value. The 3rd Thai figure (Gingrich et al. 1990; for mosquitoes only) applies to the following 2 yr in the same village; the observed mixed-species prevalence in mosquitoes again fit the product of the singles species prevalences.

The entomological studies conducted by Burkot et al. (1990, 1992) in Buksak village, Papua New Guinea, implied that the fraction of positive An. punctulatus co-infected with P. falciparum and P. vivax peaked during early 1987, shirting from 6% for 1986 to 8–9% for January 1986–March 1987 to 1% for 1987. The comparative figures for humans (from Burkot et al. 1987) apply to a 1983–1985 study of 8 other villages near Madang, and are far higher than the 1–4% found during 1981–1983 surveys of 53 villages in this coastal province (Cattani et al. 1986). In Buksak, for 1986 and 1986–1987 the observed prevalence of mixed-species infections in resting catches (6 and 9% of positives, respectively) far exceeded expected values, whereas the observed prevalence in 1987 resting catches and 1986–1987 biting catches (1 and 8% of positives, respectively) fit expected values. We were not able to derive sufficiently detailed comparable figures for humans. In the other New Guinea study, from the highlands of Irian Jaya (Anthony et al. 1992), mixed-species prevalence in mosquitoes fit the expected values; again we could not extract complete, exact comparative figures for humans from this report, but we strongly suspect that the human data show a substantial deficit of mixed-species infections.

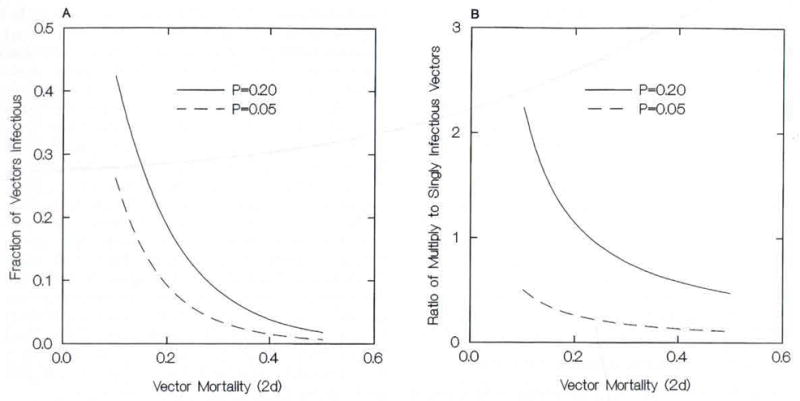

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate behaviors of our model, with a fixed 14-d incubation period (i.e., D = 7) and, for simplicity, PA = PB. Figure 1 sets PA (= PB) = 0.05 or 0.20, an idealized prevalence of infectious gametocytes in the human population (i.e., PA + PB − PAPB) of 0.0975 or 0.36, respectively. As one would expect, the infectious fraction of the mosquito population and the ratio of dually to singly infectious vectors decline with increasing vector mortality. Notice, however, that in every case the frequency of multiple infections is much larger than PAPB and much larger than observed.

Fig. 1.

Behavior of the accumulation model for 2 values of the species gametocyte prevalences in the human population, P = PA = PB, with respect to 2-d vector mortality: (A) the fraction of vectors infectious for any species or combination; (B) the ratio of vectors infectious for >1 species to those infectious for only 1.

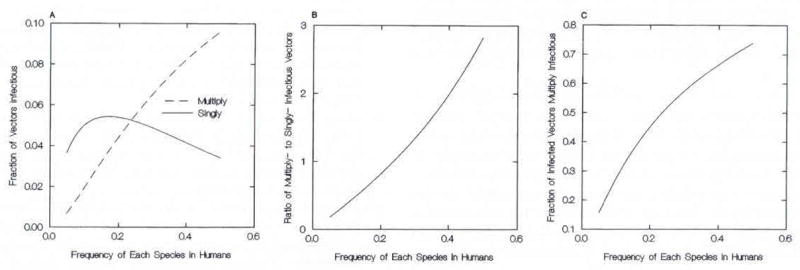

Fig. 2.

Behavior of the accumulation model, for 2-d vector mortality fixed at 0.28, with respect to the species gametocyte prevalences in the human population, P = PA = PB: (A) the fraction of vectors infectious either for a single species alone or for >1; (B) the ratio of vectors infectious for >1 species to those infectious for only 1; (C) the ratio of vectors infectious for >1 species to the total infectious.

Figure 2 fixes the vector mortality (s), at 0.28. The corresponding 0.85 daily survivorship is within published ranges for An. gambiae in East Africa, albeit near the upper end of recent ranges (e.g., Macdonald 1956, Garrett-Jones and Shidrawi 1969, Mutero and Birley 1987, Gillies 1988). The frequency of multiply infectious mosquitoes increases with increasing prevalence in humans, while the frequency of singly infectious mosquitoes attains a maximum at an intermediate value of P. Hence, with increasing P the ratio of dually to singly infectious mosquitoes increases at a slightly greater than linear rate.

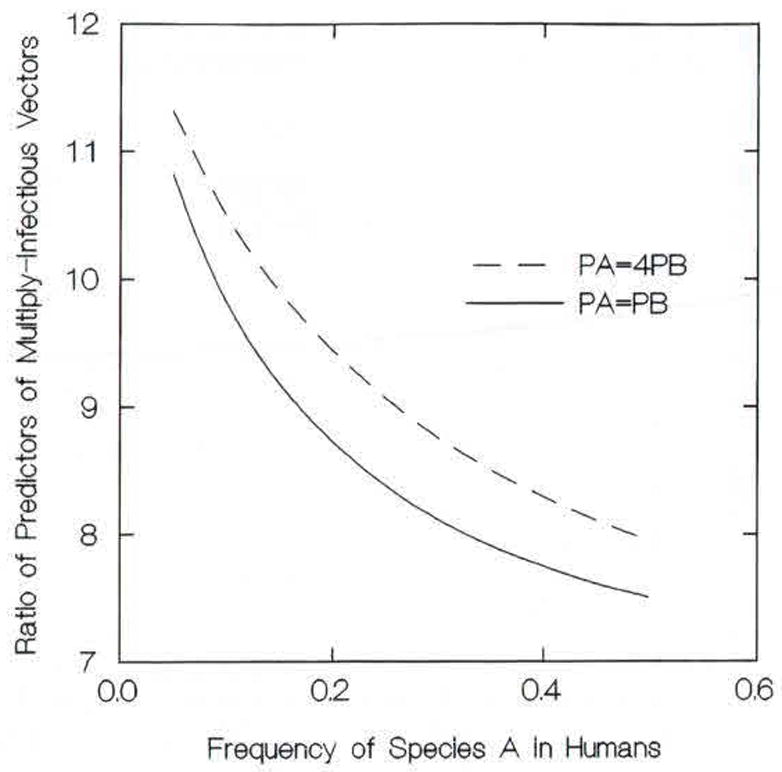

Figure 3 compares the frequencies of multiply infectious mosquitoes predicted by our model to those predicted by the product of species prevalences in infectious mosquitoes and addresses the typical case in which the gametocyte prevalences PA and PB are not equal.

Fig. 3.

Behavior of the accumulation model, for 2-d vector mortality fixed at 0.28, with respect to equal and unequal species gametocyte prevalences in the human population, PA and PB. The ratio shown divides the frequencies of multiply infectious mosquitoes predicted by the model by those predicted by the product of the species prevalences in infectious mosquitoes.

Discussion

The information compiled here indicates that many Anopheles species are capable of carrying sporozoites of >1 Plasmodium species, of doing so simultaneously under field conditions, and of acquiring and transmitting these in experimental situations. The data available to us indicate that there is wide variability in mixed-infection frequencies in humans and mosquitoes, in both absolute and relative terms, and that this variability may be related to variability in temporal, spatial, methodological or other factors. For example, we were not able to assess the effects of differing Plasmodium species composition (e.g., the potential presence of all 4 human Plasmodium species in New Guinea, or the substitution of P. ovale for P. vivax in most of Africa) or subdivisions within Anopheles species complexes. Although the sheer number and complex interconnections of such variables seem overwhelming, it may be that neither these nor many other phenomena of malaria demand detailed local explanation.

In contrast to the situation in human populations, the few data points for which absolute prevalences are available do not indicate prevalences of mixed-species infections in mosquito populations less than those expected on the basis of multiplying single-species prevalences. There is no difficulty explaining this phenomenon on the basis of the simple accumulation model presented here. What may require further explanation is that the prevalences of mixed-species infections do not reach the levels predicted by our model, with the exception of the single positive An. fluviatilis collected by Subbarao et al. (1992). A far more complex model will incorporate the possibilities that humans also accumulate infections, mosquitoes may feed on other mammals, and infectious humans may fail to infect mosquitoes. However, it appears unlikely that the net bias introduced by our simplifying assumptions would account for order-of-magnitude discrepancies. Perhaps the distinction is mediated by both relative gametocyte prevalence (Burkot et. al. 1987, Rosenberg et al. 1990b) and infectivity. Graves et al. (1988) noted that the presence of P. falciparum gametocytes appeared to reduce the infectivity of P. vivax gametocytes, but not of P. malariae gametocytes, when either was present simultaneously. We hope that future studies will address these points, the accumulation processes by which such patterns may arise, and the potential epidemiological effects (e.g., in situations in which most mixed-species infections in mosquitoes are derived from blood-meals from several different humans [Davies 1990, Conway and McBride 1991, Klowden and Briegel 1994] rather than from meals on multiply infected humans).

There are many pitfalls in the diagnosis of mixed-species infections and few precedents for the study of such infections in concurrent human and mosquito populations. However, the utility of such investigations could well reach beyond Plasmodium, Anopheles, or interactions solely at the species level. Recent studies have found Borrelia and Babesia co-infections in individual ticks (Mather et al. 1990), dual Leishmania species infections in single sandflies (Barrios et al. 1994) and mixtures of trypanosome genotypes in individual Glossina (Letch 1984, Stevens et al. 1994). Although the frequencies and implications of recombination among Plasmodium genotypes prompt debate (Tibayrenc et al. 1990, Walliker 1991, Read and Day 1992, Ranford-Cartwright et al. 1993, Babiker et al. 1994, Paul et al. 1995), there is no debate that if Plasmodium genotypes are to recombine they must co-occur as gametes in the same mosquito. It is curious that there has been little discussion of circumstances or phenotypic characteristics that might facilitate or hinder this process. Here, we suggest that at least at the species level, prospective interactions are not likely to be bounded by one-at-a-time transmission, hence phenomena that might be considered competitive or cooperative may be even more important than previously suspected. It is not clear whether the consequences of incorporating simultaneous acquisitions or losses of multiple infecting species in human epidemiological models (e.g., Cohen and Singer 1979) would be trivial or profound, but 2 recent models (May and Nowak 1995, van Baalen and Sabelis 1995) suggest the latter view.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of S. Austad, M. L. Bossert, R. Didday, P. Fischer, E. Kane, R. Schwabacher, A. Spielman, T. Tsomides, 2 anonymous reviewers, and the Countway and Mayr libraries at Harvard University. Some of this material is based on preparatory work supported under a National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship awarded to F.E.M. We appreciate the continued support of the Maurice Pechet Foundation.

References Cited

- Albuquerque CMR, Ham PJ. Concomitant malaria (Plasmodium galliaceum) filaria (Brugia pahangi) infections in Aedes aegypti: effect on parasite development. Parasitology. 1995;110:1–6. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerasinghe FP, Amerasinghe PH, Peiris JSM, Wirtz RA. Anopheline ecology and malaria infection during the irrigation development of an area of the Mahaweli Project, Sri Lanka. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:226–235. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM, May RM. Infectious diseases of humans. Oxford University; Oxford: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony RL, Bangs MJ, Hamzah N, Basri H, Purnomo, Subianto B. Heightened transmission of stable malaria in an isolated population in the highlands of Irian Java, Indonesia. Am J Trap Med Hyg. 1992;47:346–356. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiker HA, Ranford-Cartwright LC, Currie D, Charlwood JD, Billingsley P, Teuscher T, Walliker D. Random mating in a natural population of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 1994;109:413–421. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EZ, Beier JC, Meek SR, Wirtz RA. Detection and quantitation of Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax infections in Thai-Kampuchean Anopheles (Diptera; Culicidae) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Med Entomol. 1987;24:536–541. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/24.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios M, Rodriguez N, Feliciangeli DM, Ulrich M, Telles S, Pinardi ME, Convit J. Coexistence of two species of Leishmania in the digestive tract of the vector Lutzomyia ovallesi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:669–675. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach RF, Cordon-Rosales C, Molina E, Wirtz RA. Field evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for estimating the sporozoite rate in Anopheles albimanus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:478–483. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck K. Coevolution: mathematical analysis of host-parasite interactions. J Math Biol. 1984;19:63–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00275931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier JC, Onyango FK, Ramadhan M, Koros JK, Asiago CM, Wirtz RA, Koech DK, Roberts CR. Quantitation of malaria sporozoites in the salivary glands of wild Afrotropical Anopheles. Med Vet Entomol. 1991;5:63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1991.tb00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier MS, I, Schwartz K, Beier JC, Perkins PV, Oyango F, Koros JK, Campbell GH, Andrysiak PM, Brandling-Bennett AD. Identification of malaria species by ELISA in sporozoite and oocyst infected Anopheles from western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:323–327. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudin C, Robert V, Verhave JP, Carnevale P, Ambroise-Thomas P. Plasmodium falciparum and P. malariae epidemiology in a West African village. Bull WHO. 1991;69:199–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd MF, Kitchen SF, Kupper WH. The employment of multiply infected Anopheles quadrimaculatus to effect inoculation with Plasmodium vivax and P. falciparum. Am J Trop Med. 1937;17:849–853. [Google Scholar]

- Branquinho MS, Lagos CBT, Rocha RM, Natal D, Barata JMS, Cochrane AH, Nardin E, Nussenzweig RS, Kloetzel JK. Anophelines in the state ot Acre, Brazil infected with Plasmodium falcipaum, P. vivax, the variant P vivax VK247 and P malariae. Trans R Soc Trop Med, Hyg. 1993;87:391–394. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90008-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremermann HJ, Thieme HR. A competitive exclusion principle for pathogen virulence. J Math Biol. 1989;27:179–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00276102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkot TR, Graves PM, Cattani JA, Wirtz RA, Gibson FD. The efficiency of sporozoite transmission in the human malarias, Plasmodium falcipaum and P. vivax. Bull WHO. 1987;65:375–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkot TR, Molineaux L, Graves PM, Paru R, Battistutta D, Dagoro H, Barnes A, Wirtz RA, Garner P. The prevalence of naturally acquired multiple infections of wucheria bancrofti and human malarias in anophelines. Parasitology. 1990;100:369–375. doi: 10.1017/s003118200007863x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkot TR, Wirtz RA, Paru R, Garner P, Alpers MP. The population dynamics in mosquitoes and humans of two Plasmodium vivax polymorphs distinguished by different circumsporozoite protein repeat regions. Am J, Trop, Med, Hyg. 1992;47:778–786. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattani JA, Tulloch JL, Vrbova H, Jolley D, Gibson FD, Moir JS, Heywood PF, Alpers MP, Stevenson A, Claney R. The epidemiology of malaria in a population surrounding Madang, Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35:3–15. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JE. Heterologous immunity in human malaria. Q Rev Biol. 1973;48:467–489. doi: 10.1086/407705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JE, Singer B. Malaria in Nigeria: constrained continuous-time Markov models for discrete-time longitudinal data on human mixed-species infections. Lect Math Life Sci. 1979;12:69–133. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WE, Roberts JM. Anopheles gambiae as a host for geographic isolates of Plasmodium vivax. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1991;7:569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway DJ, McBride JS. Genetic evidence for the importance of interrupted feeding by mosquitoes in the transmission of malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:454–456. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90217-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies CR. Interrupted feeding of blood-sucking insects: causes and effects. Parasitol Today. 1990;6:19–22. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90387-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Arruda M, Carvalho MB, Nussenzweig RS, Maracie M, Ferreira AW, Coehrane AH. Potential vectors of malaria and their different susceptibility to Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in northern Brazil identified by immunoassay. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;35:873–881. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson AP. The population dynamics of competition between parasites. Parasitology. 1985;91:317–347. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000057401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson AP. Models for multi-species parasite-host communities. In: Esch GW, Bush AO, Aho JM, editors. Parasite communities: patterns and processes. Chapman & Hall; London: 1990. pp. 261–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson AP, Roberts M. The population dynamics of parasitic helminth communities. Parasitology. 1994;109:s97–108. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000085115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch GW, Bush AO, Aho JM. Parasite communities: patterns and processes. Chapman & Hall; London: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fontenille D, Lepers JP, Coluzzi M, Campbell GH, Rakotoarivony I, Coulanges P. Malaria transmission and vector biology on Sainte Marie Island, Madagascar. J Med Entomol. 1992;29:197–202. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/29.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox E, Strickland GT. The interrelationship of Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax in the Punjab. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:471–473. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamage-Mendis AC, Rajakaruna J, Weerasinghe S, Mendis C, Carter R, Mendis KM. Infectivity of Plasmodium vivax and P. falciparum to Anopheles tessellatus; relationship between oocyst and sporozoite development. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:3–6. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett-Jones C, Shidrawi GR. Malaria vectorial capacity of a population of Anopheles gambiae. Bull WHO. 1969;40:531–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies MT. Anopheline mosquitoes: vector behaviour and bionomics. In: Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor I, editors. Malaria. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1988. pp. 453–486. [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich JB, Weatherhead A, Sattabongkot J, Pilakasiri C, Wirtz RA. Hyperendemic malaria in a Thai village: dependence of year-round transmission on focal and seasonally circumscribed mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) habitats. J Med Entomol. 1990;27:1016–1026. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/27.6.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DM, Davis DR, Lee M, Lambros C, Harrison BA, Samuel R, Campbell GH, Jegathesan M, Selvarajan K, Lewis GE., Jr Significance of circumsporozoite-specific antibody in the natural transmission of Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium malariae in an aboriginal (Orang Asli) population of central peninsular Malaysia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:49–56. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves PM, Burkot TR, Carter R, Cattani JA, Lagog M, Parker J, Brabin BJ, Gibson FD, Bradley DJ, Alpers MP. Measurement of malarial infectivity of human populations to mosquitoes in the Madang area, Papua New Guinea. Parasitology. 1988;96:251–263. doi: 10.1017/s003118200005825x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbach RE, Gingrich JB, Pang LW. Some entomological observations on malaria transmission in a remote village in northwestern Thailand. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1987;3:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JC. Evolutionary relationships between parasitic helminths and their hosts. In: Futuyma DJ, Slatkin M, editors. Coevolution. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 1983. pp. 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CR. Ecological animal parasitology. Blaekwell Scientific; Oxford: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Klein TA, Lima JBP, Tada MS. Comparative susceptibility of anopheline mosquitoes to Plasmodium falciparum in Rondonia, Brazil. Am J Trap Med Hyg. 1991;44:598–603. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.44.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein TA, Lima JBP, Tada MS, Miller R. Comparative susceptibility of anopheline mosquitoes to Plasmodium vivax in Rondonia, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:463–470. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klowden MJ, Briegel H. Mosquito gonotrophic cycle and multiple feeding potential: contrasts between Anopheles and Aedes (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1994;31:618–622. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letch CA. A mixed population of Trypanozoon in Glossina palpalis palpalis from Ivory Coast. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:627–630. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien JC. Anopheline mosquitoes and malaria parasites in Taiwan, Kaohsiung. Med Sci. 1991;7:207–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Chittamas S, Bunnag D, Harinasuta T. High rate of Plasmodium vivax relapse following treatment of falciparum malaria in Thailand. Lancet. 1987;2:1052–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald G. Theory of the eradication of malaria. Bull WHO. 1956;15:369–387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather TN, Telford SR, III, Moore SI, Spielman A. Borrelia burgdorferi and Babesia microti: efficiency of transmission from reservoirs to vector ticks (Ixodes dammini) Exp Parasitol. 1990;70:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90085-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May RM, Nowak MA. Coinfection and the evolution of parasite virulence. Proc R Soc Lond. 1995;B261:209–215. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne B, Young MD. Antagonism between species of malaria parasites in induced mixed infections. Public Health Rep. 1938;53:1289–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Mendis C, Gamage-Mendis AC, de Zoysa APK, Abhayawardeiia TA, Carter R, Herath PRJ, Mendis KN. Characteristics of malaria transmission in Kataragama, Sri Lanka; a focus for immuno-epidemiological studies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:298–308. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molineaux L. The epidemiology of human malaria as an explanation of its distribution, including some implications for its control. In: Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor I, editors. Malaria. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1988. pp. 913–998. [Google Scholar]

- Molineaux L, Gramiccia G. The Garki Project. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead-Thomson RC. Inter-relations between filarial and malarial infections in Anopheles gambiae. Nature (Lond) 1953;172:352–353. doi: 10.1038/172352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutero CM, Birley MH. Estimation of the survival rate and oviposition cycle of field populations of malaria vectors in Kenya. J AppI, Ecol. 1987;24:853–863. [Google Scholar]

- Olano VA, Carrillo MP, de la Vega P, Espinal CA. Vector competence of Cartagena strain of Anopheles albimanus for Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79:685–686. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul REL, Packer MJ, Walmsley M, Lagog M, Ranford-Cartwright LC, Paru R, Day KP. Mating patterns in malaria parasite populations of Papua New Guinea. Science (Wash DC) 1995;269:1709–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.7569897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson SL, Poirier SJ, Grimstad PR, Craig GB., Jr Vector competence of Aedes hendersoni (Diptera: Culicidae) for La Crosse virus: lack of impaired function in virus-infected salivary glands and enhanced virus transmission by sporozoite-infected mosquitoes. J Med Entomol. 1992;29:483–488. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/29.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnudurai T, Lensen AHW, van Gemert GJ, Bolmer M, van Belkum A, van Eerd P, Mons B. Large-scale production of Plasmodium vivax sporozoites. Parasitology. 1990;101:317–320. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000060492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranford-Cartwright LC, Balfe P, Carter R, Walliker D. Frequency of cross-fertilization in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 1993;107:387–395. doi: 10.1017/s003118200007935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read AF, Day KP. The genetic structure of malaria parasite populations. Parasitol Today. 1992;8:239–242. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(92)90125-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie TL. Interactions between malaria parasites infecting the same vertebrate host. Parasitology. 1988;96:607–639. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg R, Andre RG, Ngampatom S, Hatz C, Burge R. A stable, oligosymptomatic malaria focus in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990a;84:14–21. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90366-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg R, Andre RG, Somchit L. Highly efficient dry season transmission of malaria in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990b;84:22–28. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90367-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schad GA. Niche diversification in a parasitic species flock. Nature (Lond) 1963;198:404–406. [Google Scholar]

- Shute PG. Mosquito infection in artificially induced malaria. Br Med Bull. 1951;8:56–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a074055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shute PG, Maryon M. A study of human malaria oocysts as an aid to species diagnosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46:27,5–292. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry. Freeman; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer HC, Kaseje DCO, Collins WE, Shehata MG, Turner AT, Stanfill PS, Huong AY, Roberts JM, Villinski M, Koech DK. Community-based malaria control in Saradidi, Kenya: description of the programme and impact on parasitemia rates and antimatarial antibodies. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1987;81s1:13–23. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1987.11812185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JR, Mathieu-Daude F, McNamara JJ, Mizen VH, Nzila A. Mixed populations of Trypanosoma brucei in wild Glossina palpalis palpalis. Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45:313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao SK, Vasantha K, Joshi H, Raghavendra K, Usha Devi C, Sathyanarayan TS, Cochrane AH, Nussenzweig RS, Sharma VP. Role of Anopheles culifacies sibling species in malaria transmission in Madhya Pradesh state, India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:613–614. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibayrenc M, Kjellberg F, Ayala FJ. A clonal theory of parasitic protozoa: the population structures of Entamoeba, Giardia, Leishmania, Naegleria, Plasmodium, Trichomonas, and Trypanosoma and their medical and taxonomical consequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2414–2418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trape JF, Rogier C, Konate L, Diagne N, Bouganali H, Canque B, Legros F, Badji A, Ndiaye G, Ndiaye P, Brahimi K, Faye O, Druilhe P, da Silva LP. The Dielmo Project: a longitudinal study of natural malaria infection and the mechanisms of protective immunity in a community living in a holoendemic area of Senegal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:123–137. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turell MJ, Rossignol PA, Spielman A, Rossi CA, Bailey CL. Enhanced arboviral transmission by mosquitoes that concurrently ingested microfilariae. Science (Wash DC) 1984;225:1039–1041. doi: 10.1126/science.6474165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Baalen M, Sabelis MW. The dynamics of multiple infection and the evolution of virulence. Am Nat. 1995;146:881–910. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan JA, Turell MJ. Dual host infections: enhanced infectivity of eastern equine encephalitis virus to Aedes mosquitoes mediated by Brugia microfilariae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:105–109. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walliker D. Malaria parasites: randomly interbreeding or 'clonaT populations? Parasitol Today. 1991;7:232–235. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(91)90235-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor I. Malaria. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz RA, Burkot TR, Graves PM, Andre RG. Field evaluation of enzyme-linked hri-munosorbent assays for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax sporozoites in mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from Papua New Guinea. J Med Entomol. 1987;24:433–437. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/24.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]