Abstract

This article reviews recent research on cannabinoid analgesia via the endocannabinoid system and non-receptor mechanisms, as well as randomized clinical trials employing cannabinoids in pain treatment. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, Marinol®) and nabilone (Cesamet®) are currently approved in the United States and other countries, but not for pain indications. Other synthetic cannabinoids, such as ajulemic acid, are in development. Crude herbal cannabis remains illegal in most jurisdictions but is also under investigation. Sativex®, a cannabis derived oromucosal spray containing equal proportions of THC (partial CB1 receptor agonist ) and cannabidiol (CBD, a non-euphoriant, anti-inflammatory analgesic with CB1 receptor antagonist and endocannabinoid modulating effects) was approved in Canada in 2005 for treatment of central neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis, and in 2007 for intractable cancer pain. Numerous randomized clinical trials have demonstrated safety and efficacy for Sativex in central and peripheral neuropathic pain, rheumatoid arthritis and cancer pain. An Investigational New Drug application to conduct advanced clinical trials for cancer pain was approved by the US FDA in January 2006. Cannabinoid analgesics have generally been well tolerated in clinical trials with acceptable adverse event profiles. Their adjunctive addition to the pharmacological armamentarium for treatment of pain shows great promise.

Keywords: cannabinoids, tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol, analgesia, pain management, multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Chronic pain represents an emerging public health issue of massive proportions, particularly in view of aging populations in industrialized nations. Associated facts and figures are daunting: In Europe, chronic musculoskeletal pain of a disabling nature affects over one in four elderly people (Frondini et al 2007), while figures from Australia note that older half of older people suffer persistent pain, and up to 80% in nursing home populations (Gibson 2007). Responses to an ABC News poll in the USA indicated that 19% of adults (38 million) have chronic pain, and 6% (or 12 million) have utilized cannabis in attempts to treat it (ABC News et al 2005).

Particular difficulties face the clinician managing intractable patients afflicted with cancer-associated pain, neuropathic pain, and central pain states (eg, pain associated with multiple sclerosis) that are often inadequately treated with available opiates, antidepressants and anticonvulsant drugs. Physicians are seeking new approaches to treatment of these conditions but many remain concerned about increasing governmental scrutiny of their prescribing practices (Fishman 2006), prescription drug abuse or diversion. The entry of cannabinoid medicines to the pharmacopoeia offers a novel approach to the issue of chronic pain management, offering new hope to many, but also stoking the flames of controversy among politicians and the public alike.

This article will attempt to present information concerning cannabinoid mechanisms of analgesia, review randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of available and emerging cannabinoid agents, and address the many thorny issues that have arisen with clinical usage of herbal cannabis itself (“medical marijuana”). An effort will be made to place the issues in context and suggest rational approaches that may mitigate concerns and indicate how standardized pharmaceutical cannabinoids may offer a welcome addition to the pharmacotherapeutic armamentarium in chronic pain treatment.

Cannabinoids and analgesic mechanisms

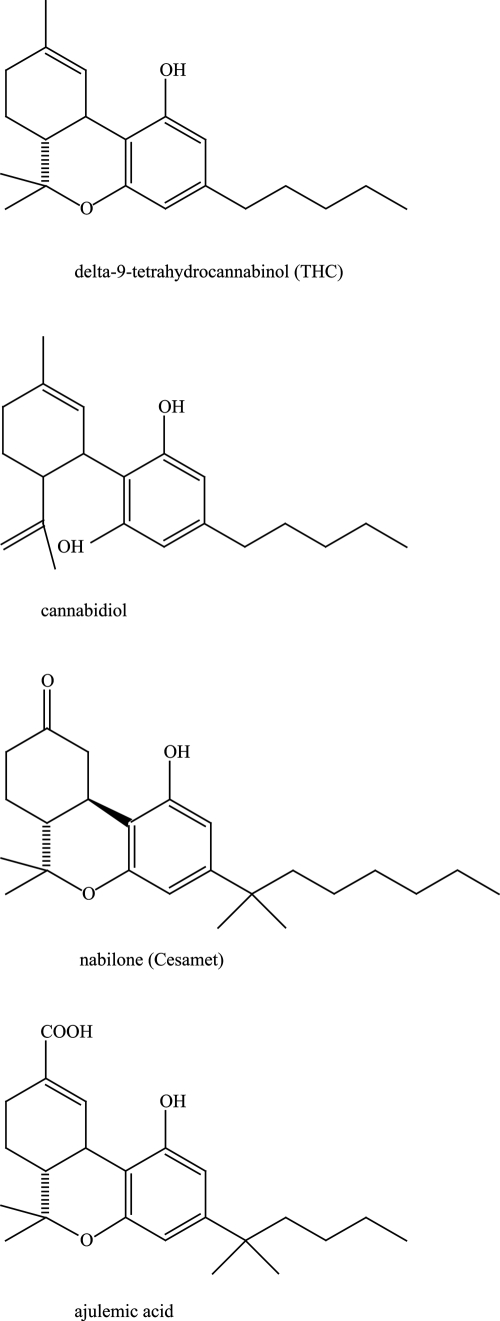

Cannabinoids are divided into three groups. The first are naturally occurring 21-carbon terpenophenolic compounds found to date solely in plants of the Cannabis genus, currently termed phytocannabinoids (Pate 1994). The best known analgesic of these is Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (henceforth, THC)(Figure 1), first isolated and synthesized in 1964 (Gaoni and Mechoulam 1964). In plant preparations and whole extracts, its activity is complemented by other “minor” phytocannabinoids such as cannabidiol (CBD) (Figure 1), cannabis terpenoids and flavonoids, as will be discussed subsequently.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of four cannabinoids employed in pain treatment.

Long before mechanisms of cannabinoid analgesia were understood, structure activity relationships were investigated and a number of synthetic cannabinoids have been developed and utilized in clinical trials, notably nabilone (Cesamet®, Valeant Pharmaceuticals), and ajulemic acid (CT3, IP-751, Indevus Pharmaceuticals) (Figure 1).

In 1988, the first cannabinoid receptor was identified (CB1) (Howlett et al 1988) and in 1993, a second was described (CB2) (Munro et al 1993). Both are 7-domain G-protein coupled receptors affecting cyclic-AMP, but CB1 is more pervasive throughout the body, with particular predilection to nociceptive areas of the central nervous system and spinal cord (Herkenham et al 1990; Hohmann et al 1999), as well as the peripheral nervous system (Fox et al 2001; Dogrul et al 2003) wherein synergy of activity between peripheral and central cannabinoid receptor function has been demonstrated (Dogrul et al 2003). CB2, while commonly reported as confined to lymphoid and immune tissues, is also proving to be an important mediator for suppressing both pain and inflammatory processes (Mackie 2006). Following the description of cannabinoid receptors, endogenous ligands for these were discovered: anandamide (arachidonylethanolamide, AEA) in 1992 in porcine brain (Devane et al 1992), and 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG) in 1995 in canine gut tissue (Mechoulam et al 1995) (Figure 1). These endocannabinoids both act as retrograde messengers on G-protein coupled receptors, are synthesized on demand, and are especially active on glutamatergic and GABA-ergic synapses. Together, the cannabinoid receptors, their endogenous ligands (“endocannabinoids”) and metabolizing enzymes comprise the endocannabinoid system (ECS) (Di Marzo et al 1998), whose functions have been prosaically termed to be “relax, eat, sleep, forget and protect” (p. 528). The endocannabinoid system parallels and interacts at many points with the other major endogenous pain control systems: endorphin/enkephalin, vanilloid/transient receptor potential (TRPV), and inflammatory. Interestingly, our first knowledge of each pain system has derived from investigation of natural origin analgesic plants, respectively: cannabis (Cannabis sativa, C. indica) (THC, CBD and others), opium poppy (Papaver somniferun) (morphine, codeine), chile peppers (eg, Capsicum annuum, C. frutescens, C. chinense) (capsaicin) and willow bark (Salix spp.) (salicylic acid, leading to acetylsalicylic acid, or aspirin). Interestingly, THC along with AEA and 2-AG, are all partial agonists at the CB1 receptor. Notably, no endocannabinoid has ever been administered to humans, possibly due to issues of patentability and lack of commercial feasibility (Raphael Mechoulam, pers comm 2007). For an excellent comprehensive review of the endocannabinoid system, see Pacher et al (2006), while Walker and Huang have provided a key review of antinociceptive effects of cannabinoids in models of acute and persistent pain (Walker and Huang 2002).

A clinical endocannabinoid deficiency has been postulated to be operative in certain treatment-resistant conditions (Russo 2004), and has received recent support in findings that anandamide levels are reduced over controls in migraineurs (Sarchielli et al 2006), that a subset of fibromyalgia patients reported significant decreased pain after THC treatment (Schley et al 2006), and the active role of the ECS in intestinal pain and motility in irritable bowel syndrome (Massa and Monory 2006) wherein anecdotal efficacy of cannabinoid treatments have also been claimed.

The endocannabinoid system is tonically active in control of pain, as demonstrated by the ability of SR141716A (rimonabant), a CB1 antagonist, to produce hyperalgesia upon administration to mice (Richardson et al 1997). As mentioned above, the ECS is active throughout the neuraxis, including integrative functions in the periacqueductal gray (Walker et al 1999a; Walker et al 1999b), and in the ventroposterolateral nucleus of the thalamus, in which cannabinoids proved to be 10-fold more potent than morphine in wide dynamic range neurons mediating pain (Martin et al 1996). The ECS also mediates central stress-induced analgesia (Hohmann et al 2005), and is active in nociceptive spinal areas (Hohmann et al 1995; Richardson et al 1998a) including mechanisms of wind-up (Strangman and Walker 1999) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Richardson et al 1998b). It was recently demonstrated that cannabinoid agonists suppress the maintenance of vincristine-induced allodynia through activation of CB1 and CB2 receptors in the spinal cord (Rahn et al 2007). The ECS is also active peripherally (Richardson et al 1998c) where CB1 stimulation reduces pain, inflammation and hyperalgesia. These mechanisms were also proven to include mediation of contact dermatitis via CB1 and CB2 with benefits of THC noted systemically and locally on inflammation and itch (Karsak et al 2007). Recent experiments in mice have even suggested the paramount importance of peripheral over central CB1 receptors in nociception of pain (Agarwal et al 2007)

Cannabinoid agonists produce many effects beyond those mediated directly on receptors, including anti-inflammatory effects and interactions with various other neurotransmitter systems (previously reviewed (Russo 2006a). Briefly stated, THC effects in serotonergic systems are widespread, including its ability to decrease 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) release from platelets (Volfe et al 1985), increase its cerebral production and decrease synaptosomal uptake (Spadone 1991). THC may affect many mechanisms of the trigeminovascular system in migraine (Akerman et al 2003; Akerman et al 2004; Akerman et al 2007; Russo 1998; Russo 2001). Dopaminergic blocking actions of THC (Müller-Vahl et al 1999) may also contribute to analgesic benefits.

The glutamatergic system is integral to development and maintenance of neuropathic pain, and is responsible for generating secondary and tertiary hyperalgesia in migraine and fibromyalgia via NMDA mechanisms (Nicolodi et al 1998). Thus, it is important to note that cannabinoids presynaptically inhibit glutamate release (Shen et al 1996), THC produces 30%–40% reduction in NMDA responses, and THC is a neuroprotective antioxidant (Hampson et al 1998). Additionally, cannabinoids reduce hyperalgesia via inhibition of calcitonin gene-related peptide (Richardson et al 1998a). As for Substance P mechanisms, cannabinoids block capsaicin-induced hyperalgesia (Li et al 1999), and THC will do so at sub-psychoactive doses in experimental animals (Ko and Woods 1999). Among the noteworthy interactions with opiates and the endorphin/enkephalin system, THC has been shown to stimulate beta-endorphin production (Manzanares et al 1998), may allow opiate sparing in clinical application (Cichewicz et al 1999), prevents development of tolerance to and withdrawal from opiates (Cichewicz and Welch 2003), and rekindles opiate analgesia after a prior dosage has worn off (Cichewicz and McCarthy 2003). These are all promising attributes for an adjunctive agent in treatment of clinical chronic pain states.

The anti-inflammatory contributions of THC are also extensive, including inhibition of PGE-2 synthesis (Burstein et al 1973), decreased platelet aggregation (Schaefer et al 1979), and stimulation of lipooxygenase (Fimiani et al 1999). THC has twenty times the anti-inflammatory potency of aspirin and twice that of hydrocortisone (Evans 1991), but in contrast to all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), demonstrates no cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibition at physiological concentrations (Stott et al 2005a).

Cannabidiol, a non-euphoriant phytocannabinoid common in certain strains, shares neuroprotective effects with THC, inhibits glutamate neurotoxicity, and displays antioxidant activity greater than ascorbic acid (vitamin C) or tocopherol (vitamin E) (Hampson et al 1998). While THC has no activity at vanilloid receptors, CBD, like AEA, is a TRPV1 agonist that inhibits fatty acid amidohydrolase (FAAH), AEA’s hydrolytic enzyme, and also weakly inhibits AEA reuptake (Bisogno et al 2001). These activities reinforce the conception of CBD as an endocannabinoid modulator, the first clinically available (Russo and Guy 2006). CBD additionally affects THC function by inhibiting first pass hepatic metabolism to the possibly more psychoactive 11-hydroxy-THC, prolonging its half-life, and reducing associated intoxication, panic, anxiety and tachycardia (Russo and Guy 2006). Additionally, CBD is able to inhibit tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in its own right in a rodent model of rheumatoid arthritis (Malfait et al 2000). At a time when great concern is accruing in relation to NSAIDs in relation to COX-1 inhibition (gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeding) and COX-2 inhibition (myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accidents), CBD, like THC, inhibits neither enzyme at pharmacologically relevant doses (Stott et al 2005a). A new explanation of inflammatory and analgesic effects of CBD has recently come to light with the discovery that it is able to promote signaling of the adenosine receptor A2A by inhibiting the adenosine transporter (Carrier et al 2006).

Other “minor phytocannabinoids” in cannabis may also contribute relevant activity (McPartland and Russo 2001). Cannabichromene (CBC) is the third most prevalent cannabinoid in cannabis, and is also anti-inflammatory (Wirth et al 1980), and analgesic, if weaker than THC (Davis and Hatoum 1983). Cannabigerol (CBG) displays sub-micromolar affinity for CB1 and CB2 (Gauson et al 2007). It also exhibits GABA uptake inhibition to a greater extent than THC or CBD (Banerjee et al 1975), suggesting possible utilization as a muscle relaxant in spasticity. Furthermore, CBG has more potent analgesic, anti-erythema and lipooxygenase blocking activity than THC (Evans 1991), mechanisms that merit further investigation. It requires emphasis that drug stains of North American (ElSohly et al 2000; Mehmedic et al 2005), and European (King et al 2005) cannabis display relatively high concentrations of THC, but are virtually lacking in CBD or other phytocannabinoid content.

Cannabis terpenoids also display numerous attributes that may be germane to pain treatment (McPartland and Russo 2001). Myrcene is analgesic, and such activity, in contrast to cannabinoids, is blocked by naloxone (Rao et al 1990), suggesting an opioid-like mechanism. It also blocks inflammation via PGE-2 (Lorenzetti et al 1991). The cannabis sesquiterpenoid β-caryophyllene shows increasing promise in this regard. It is anti-inflammatory comparable to phenylbutazone via PGE-1 (Basile et al 1988), but simultaneously acts as a gastric cytoprotective (Tambe et al 1996). The analgesic attributes of β-caryophyllene are increasingly credible with the discovery that it is a selective CB2 agonist (Gertsch et al 2007), with possibly broad clinical applications. α-Pinene also inhibits PGE-1 (Gil et al 1989), while linalool displays local anesthetic effects (Re et al 2000).

Cannabis flavonoids in whole cannabis extracts may also contribute useful activity (McPartland and Russo 2001). Apigenin inhibits TNF-α (Gerritsen et al 1995), a mechanism germane to multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Cannflavin A, a flavone unique to cannabis, inhibits PGE-2 thirty times more potently than aspirin (Barrett et al 1986), but has not been subsequently investigated.

Finally, β-sitosterol, a phytosterol found in cannabis, reduced topical inflammation 65% and chronic edema 41% in skin models (Gomez et al 1999).

Available cannabinoid analgesic agents and those in development

Very few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted using smoked cannabis (Campbell et al 2001) despite many anecdotal claims (Grinspoon and Bakalar 1997). One such study documented slight weight gain in HIV/AIDS subjects with no significant immunological sequelae (Abrams et al 2003). A recent brief trial of smoked cannabis (3.56% THC cigarettes 3 times daily) in HIV-associated neuropathy showed positive results on daily pain, hyperalgesia and 30% pain reduction (vs 15% in placebo) in 50 subjects over a treatment course of only 5 days (Abrams et al 2007) (Table 1). This short clinical trial also demonstrated prominent adverse events associated with intoxication. In Canada, 21 subjects with chronic pain sequentially smoked single inhalations of 25 mg of cannabis (0, 2.5, 6.0, 9.5% THC) via a pipe three times a day for 5 days to assess effects on pain (Ware et al 2007) with results the authors termed “modest”: no changes were observed in acute neuropathic pain scores, and a very low number of subjects noted 30% pain relief at the end of the study (Table 1). Even after political and legal considerations, it remains extremely unlikely that crude cannabis could ever be approved by the FDA as a prescription medicine as outlined in the FDA Botanical Guidance document (Food and Drug Administration 2004; Russo 2006b), due to a lack of rigorous standardization of the drug, an absence of Phase III clinical trials, and pulmonary sequelae (bronchial irritation and cough) associated with smoking (Tashkin 2005). Although cannabis vaporizers reduce potentially carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons, they have not been totally eliminated by this technology (Gieringer et al 2004; Hazekamp et al 2006).

Table 1.

Results RCTs of cannabinoids in treatment of pain syndromes ()

| Drug | Subject number N = | RCT indication | Trial duration | Results/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajulemic Acid | 21 | Neuropathic pain | 7 day crossover | VAS improved over placebo (p = 0.02) (Karst et al 2003) |

| Cannabis, smoked | 50 | HIV neuropathy | 5 days | Decreased daily pain (p = 0.03) and hyperalgesia (p = 0.05), 52% with >30% pain reduction vs placebo (p = 0.04) (Abrams et al 2007) |

| Cannabis, Smoked | 21 | Chronic neuropathic pain | 5 days | No acute benefit on pain, average daily pain lower on high THC cannabis vs placebo (p = 0.02 ) (Ware et al 2007) |

| Cannador | 419 | Pain due to spasm in MS | 15 weeks | Improvement over placebo in subjective pain associated with spasm (p = 0.003) (Zajicek et al 2003) |

| Cannador | 65 | Post-herpetic neuralgia | 4 weeks | No benefit observed (Ernst et al 2005) |

| Cannador | 30 | Post-operative pain | Single doses, daily | Decreasing pain intensity with increased dose (p = 0.01)(Holdcroft et al 2006) |

| Marinol | 24 | Neuropathic pain in MS | 15–21 days, crossover | Median numerical pain (p = 0.02), median pain relief improved (p = 0.035) over placebo (Svendsen et al 2004) |

| Marinol | 40 | Post-operative pain | Single dose | No benefit observed over placebo (Buggy et al 2003) |

| Nabilone | 41 | Post-operative pain | 3 doses in 24 hours | NSD morphine consumption. Increased pain at rest and on movement with nabilone 1 or 2 mg (Beaulieu 2006) |

| Sativex | 20 | Neurogenic pain | Series of 2-week N-of-1 crossover blocks | Improvement with Tetranabinex and Sativex on VAS pain vs placebo (p < 0.05), symptom control best with Sativex (p < 0.0001) (Wade et al 2003) |

| Sativex | 24 | Chronic intractable pain | 12 weeks, series of N-of-1 crossover blocks | VAS pain improved over placebo (p < 0.001) especially in MS (p < 0.0042) (Notcutt et al 2004) |

| Sativex | 48 | Brachial plexus avulsion | 6 weeks in 3 two-week crossover blocks | Benefits noted in Box Scale-11 pain scores with Tetranabinex (p = 0.002) and Sativex (p = 0.005) over placebo (Berman et al 2004) |

| Sativex | 66 | Central neuropathic pain in MS | 5 weeks | NRS analgesia improved over placebo (p = 0.009) (Rog et al 2005) |

| Sativex | 125 | Peripheral neuropathic pain | 5 weeks | Improvements in NRS pain levels (p = 0.004), dynamic allodynia (p = 0.042), and punctuate allodynia (p = 0.021) vs placebo (Nurmikko et al 2007) |

| Sativex | 56 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Nocturnal dosing for 5 weeks | Improvements over placebo morning pain on movement (p = 0.044), morning pain at rest (p = 0.018), DAS-28 (p = 0.002), and SF-MPQ pain at present (p = 0.016) (Blake et al 2006) |

| Sativex | 117 | Pain after spinal injury | 10 days | NSD in NRS pain socres, but improved Brief Pain Inventory (p = 0.032), and Patients Global Impression of Change (p = 0.001) (unpublished) |

| Sativex | 177 | Intractable cancer pain | 2 weeks | Improvements in NRS analgesia vs placebo (p = 0.0142), Tetranabinex NSD (Johnson and Potts 2005) |

| Sativex | 135 | Intractable lower urinary tract symptoms in MS | 8 weeks | Improved bladder severity symptoms including pain over placebo (p = 0.001) (unpublished) |

Abbreviations: MS, multiple sclerosis; NRS, numerical rating scale; NSD, no signifi cant difference; RCTs, randomized clinical trials; VAS, visual analogue pain scales.

Oral dronabinol (THC) is marketed in synthetic form as Marinol® (Solvay Pharmaceuticals) in various countries, and was approved in the USA for nausea associated with chemotherapy in 1985, and in 1992 for appetite stimulation in HIV/AIDS. Oral dronabinol’s expense, variability of action, and attendant intoxication and dysphoria have limited its adoption by clinicians (Calhoun et al 1998). Two open label studies in France of oral dronabinol for chronic neuropathic pain in 7 subjects (Clermont-Gnamien et al 2002) and 8 subjects (Attal et al 2004), respectively, failed to show significant benefit on pain or other parameters, and showed adverse event frequently requiring discontinuation with doses averaging 15–16.6 mg THC. Dronabinol did demonstrate positive results in a clinical trial of multiple sclerosis pain in two measures (Svendsen et al 2004), but negative results in post-operative pain (Buggy et al 2003) (Table 1). Another uncontrolled case report in three subjects noted relief of intractable pruritus associated with cholestatic jaundice employing oral dronabinol (Neff et al 2002). Some authors have noted patient preference for whole cannabis preparations over oral THC (Joy et al 1999), and the contribution of other components beyond THC to therapeutic benefits (McPartland and Russo 2001). Inhaled THC leads to peak plasma concentration within 3–10 minutes, followed by a rapid fall while levels of intoxication are still rising, and with systemic bioavailability of 10%–35% (Grotenhermen 2004). THC absorption orally is slow and erratic with peak serum levels in 45–120 minutes or longer. Systemic bioavailability is also quite low due to rapid hepatic metabolism on first pass to 11-hydroxy-THC. A rectal suppository of THC-hemisuccinate is under investigation (Broom et al 2001), as are transdermal delivery techniques (Challapalli and Stinchcomb 2002). The terminal half-life of THC is quite prolonged due to storage in body lipids (Grotenhermen 2004).

Nabilone (Cesamet) (Figure 1), is a synthetic dimethylheptyl analogue of THC (British Medical Association 1997) that displays greater potency and prolonged half-life. Serum levels peak in 1–4 hours (Lemberger et al 1982). It was also primarily developed as an anti-emetic in chemotherapy, and was recently re-approved for this indication in the USA. Prior case reports have noted analgesic effects in case reports in neuropathic pain (Notcutt et al 1997) and other pain disorders (Berlach et al 2006). Sedation and dysphoria were prominent sequelae. An RCT of nabilone in 41 post-operative subjects actually documented exacerbation of pain scores after thrice daily dosing (Beaulieu 2006) (Table 1). An abstract of a study of 82 cancer patients on nabilone claimed improvement in pain levels after varying periods of follow-up compared to patients treated without this agent (Maida 2007). However, 17 subjects dropped out, and the study was neither randomized nor controlled, and therefore is not included in Table 1.

Ajulemic acid (CT3, IP-751) (Figure 1), another synthetic dimethylheptyl analogue, was employed in a Phase II RCT in 21 subjects with improvement in peripheral neuropathic pain (Karst et al 2003) (Table 1). Part of its analgesic activity may relate to binding to intracellular peroxisome proliferator-activator receptor gamma (Liu et al 2003). Peak plasma concentrations have generally been attained in 1–2 hours, but with delays up to 4–5 hours is some subjects (Karst et al 2003). Debate surrounds the degree of psychoactivity associated with the drug (Dyson et al 2005). Current research is confined to the indication of interstitial cystitis.

Cannador® (IKF-Berlin) is a cannabis extract administered in oral capsules, with differing figures as to THC:CBD ratios (reviewed in (Russo and Guy 2006)), generally approximately 2:1. Two pharmacokinetic studies on possibly related material have been reported (Nadulski et al 2005a; Nadulski et al 2005b). In a Phase III RCT employing Cannador in spasticity in multiple sclerosis (MS) (CAMS) (Zajicek et al 2003) (Table 1), no improvement was noted in the Ashworth Scale, but benefit was observed in spasm-associated pain on subjective measures. Both Marinol and Cannador produced reductions in pain scores in long-term follow-up (Zajicek et al 2005). Cannador was assayed in postherpetic neuralgia in 65 subjects with no observed benefit (Ernst et al 2005) (Table 1), and in 30 post-operative pain subjects (CANPOP) without opiates, with slight benefits, but prominent psychoactive sequelae (Holdcroft et al 2006) (Table 1).

Sativex® (GW Pharmaceuticals) is an oromucosal whole cannabis-based spray combining a CB1 partial agonist (THC) with a cannabinoid system modulator (CBD), minor cannabinoids and terpenoids plus ethanol and propylene glycol excipients and peppermint flavoring (McPartland and Russo 2001; Russo and Guy 2006). It was approved by Health Canada in June 2005 for prescription for central neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis, and in August 2007, it was additionally approved for treatment of cancer pain unresponsive to optimized opioid therapy. Sativex is a highly standardized pharmaceutical product derived from two Cannabis sativa chemovars following Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) (de Meijer 2004), yielding Tetranabinex® (predominantly-THC extract) and Nabidiolex® (predominantly-CBD extract) in a 1:1 ratio. Each 100 μL pump-action oromucosal Sativex spray actuation provides 2.7 mg of THC and 2.5 mg of CBD. Pharmacokinetic data are available, and indicate plasma half lives of 85 minutes for THC, 130 minutes for 11-hydroxy-THC and 100 minutes for CBD (Guy and Robson 2003). Sativex effects commence in 15–40 minutes, an interval that permits symptomatic dose titration. A very favorable adverse event profile has been observed in over 2500 patient years of exposure in over 2000 experimental subjects. Patients most often ascertain an individual stable dosage within 7–10 days that provides therapeutic relief without unwanted psychotropic effects (often in the range of 8–10 sprays per day). In all RCTs, Sativex was adjunctively added to optimal drug regimens in subjects with intractable symptoms, those often termed “untreatable.” Sativex is also available by named patient prescription in the UK and the Catalonia region of Spain. An Investigational New Drug (IND) application to study Sativex in advanced clinical trials in the USA was approved by the FDA in January 2006 in patients with intractable cancer pain.

The clinical trials performed with Sativex have recently been assessed in two independent review articles (Barnes 2006; Pérez 2006). In a Phase II clinical trial in 20 patients with neurogenic symptoms (Wade et al 2003), Tetranabinex, Nabidiolex, and Sativex were tested in a double-blind RCT vs placebo (Table 1). Significant improvement was seen with both Tetranabinex and Sativex on pain (especially neuropathic), but post-hoc analysis showed symptom control was best with Sativex (p < 0.0001), with less intoxication than with THC-predominant extract.

In a Phase II double-blind crossover study of intractable chronic pain (Notcutt et al 2004) in 24 subjects, visual analogue scales (VAS) were 5.9 for placebo, 5.45 for Nabidiolex, 4.63 for Tetranabinex and 4.4 for Sativex extracts (p < 0.001). Sativex produced best results for pain in MS subjects (p < 0.0042) (Table 1).

In a Phase III study of pain associated due to brachial plexus avulsion (N = 48) (Berman et al 2004), fairly comparable benefits were noted in Box Scale-11 pain scores with Tetranabinex and Sativex extracts (Table 1).

In a controlled double-blind RCT of central neuropathic pain, 66 MS subjects showed mean Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) analgesia favoring Sativex over placebo (Rog et al 2005) (Table 1).

In a Phase III double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (N = 125) of peripheral neuropathic pain with allodynia (Nurmikko et al 2007), Sativex produced highly statistically significant improvements in pain levels, dynamic and punctate allodynia (Table 1).

In a SAFEX study of Phase III double-blind RCT in 160 subjects with various symptoms of MS (Wade et al 2004), 137 patients elected to continue on Sativex after the initial study (Wade et al 2006). Rapid declines were noted in the first twelve weeks in pain VAS (N = 47) with slower sustained improvements for more than one year. During that time, there was no escalation of dose indicating an absence of tolerance to the preparation. Similarly, no withdrawal effects were noted in a subset of patients who voluntarily stopped the medicine abruptly. Upon resumption, benefits resumed at the prior established dosages.

In a Phase II double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 5-week study of 56 rheumatoid arthritis patients with Sativex (Blake et al 2006), employed nocturnal treatment only to a maximum of 6 sprays per evening (16.2 mg THC + 15 mg CBD). In the final treatment week, morning pain on movement, morning pain at rest, DAS-28 measure of disease activity, and SF-MPQ pain at present all favored Sativex over placebo (Table 1).

Results of a Phase III study (N = 177) comparing Sativex, THC-predominant extract and placebo in intractable pain due to cancer unresponsive to opiates (Johnson and Potts 2005) demonstrated that Sativex produced highly statistically significant improvements in analgesia (Table 1), while the THC-predominant extract failed to produce statistical demarcation from placebo, suggesting the presence of CBD in the Sativex preparation was crucial to attain significant pain relief.

In a study of spinal injury pain, NRS of pain were not statistically different from placebo, probably due to the short duration of the trial, but secondary endpoints were clearly positive (Table 1). Finally, in an RCT of intractable lower urinary tract symptoms in MS, accompanying pain in affected patients was prominently alleviated (Table 1).

Highly statistically significant improvements have been observed in sleep parameters in virtually all RCTs performed with Sativex in chronic pain conditions leading to reduced “symptomatic insomnia” due to symptom reduction rather than sedative effects (Russo et al 2007).

Common adverse events (AE) of Sativex acutely in RCTs have included complaints of bad taste, oral stinging, dry mouth, dizziness, nausea or fatigue, but do not generally necessitate discontinuation, and prove less common over time. While there have been no head-to-head comparative RCTs of Sativex with other cannabinoid agents, certain contrasts can be drawn. Sativex (Rog et al 2005) and Marinol (Svendsen et al 2004) have both been examined in treatment of central neuropathic pain in MS, with comparable results (Table 1). However, adverse events were comparable or greater with Marinol than with Sativex employing THC dosages some 2.5 times higher due to the presence of accompanying CBD (Russo 2006b; Russo and Guy 2006).

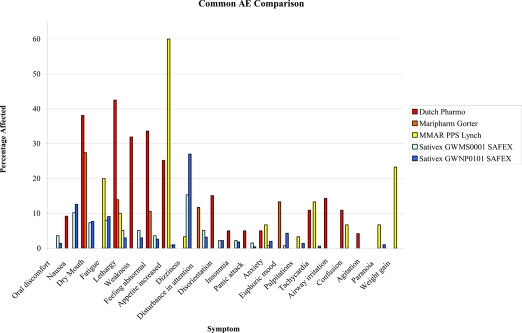

Similarly, while Sativex and smoked cannabis have not been employed in the same clinical trial, comparisons of side effect profiles can be made on the basis of SAFEX studies of Sativex for over a year and up to several years in MS and other types of neuropathic pain (Russo 2006b; Wade et al 2006), and government-approved research programs employing standardized herbal cannabis from Canada for chronic pain (Lynch et al 2006) and the Netherlands for general conditions (Janse et al 2004; Gorter et al 2005) over a period of several months or more. As is evident in Figure 2 (Figure 2), all adverse events are more frequently reported with herbal cannabis, except for nausea and dizziness, both early and usually transiently reported with Sativex (see (Russo 2006b) for additional discussion).

Figure 2.

Comparison of adverse events (AE) encountered with long term therapeutic use of herbal cannabis in the Netherlands (Janse et al 2004; Gorter et al 2005) and Canada (Lynch et al 2006), vs that observed in safety-extension (SAFEX) studies of Sativex oromucosal spray (Russo 2006; Wade et al 2006).

Practical issues with cannabinoid medicines

Phytocannabinoids are lipid soluble with slow and erratic oral absorption. While cannabis users claim that the smoking of cannabis allows easy dose titration as a function of rapid onset, high serum levels in a short interval inevitably result. This quick onset is desirable for recreational purposes, wherein intoxication is the ultimate goal, but aside from paroxysmal disorders (eg, episodic trigeminal neuralgia or cluster headache attack), such rapid onset of activity is not usually necessary for therapeutic purposes in chronic pain states. As more thoroughly reviewed elsewhere (Russo 2006b), cannabis smoking produces peak levels of serum THC above 140 ng/mL (Grotenhermen 2003; Huestis et al 1992), while comparable amounts of THC in Sativex administered oromucosally remained below 2 ng/mL (Guy and Robson 2003).

The vast majority of subjects in Sativex clinical trials do not experience psychotropic effects outside of initial dose titration intervals (Figure 2) and most often report subjective intoxication levels on visual analogue scales that are indistinguishable from placebo, in the single digits out of 100 (Wade et al 2006). Thus, it is now longer tenable to claim that psychoactive effects are a necessary prerequisite to symptom relief in the therapeutic setting with a standardized intermediate onset cannabis-based preparation. Intoxication has remained a persistent issue in Marinol usage (Calhoun et al 1998), in contrast.

Recent controversies have arisen in relation to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), with concerns that COX-1 agents may provoke gastrointestinal ulceration and bleeding, and COX-2 drugs may increase incidents of myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accidents (Fitzgerald 2004; Topol 2004). In contrast, neither THC nor CBD produce significant COX inhibition at normal dosage levels (Stott et al 2005a).

Frequent questions have been raised as to whether psychoactive drugs may be adequately blinded (masked) in randomized clinical trials. Internal review and outside analysis have confirmed that blinding in Sativex spasticity studies has been effective (Clark and Altman 2006; Wright 2005). Sativex and its placebo are prepared to appear identical in taste and color. About half of clinical trial subjects reported previous cannabis exposure, but results of two studies (Rog et al 2005; Nurmikko et al 2007) support the fact that cannabis-experienced and naïve patients were identical in observed efficacy and adverse event reporting

Great public concern attends recreational cannabis usage and risks of dependency. The addictive potential of a drug is assessed on the basis of five elements: intoxication, reinforcement, tolerance, withdrawal and dependency. Drug abuse liability (DAL) is also assessed by examining a drug's rates of abuse and diversion. US Congress placed cannabis in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act in 1970, with drugs categorized as addictive, dangerous, possessing severe abuse potential and no recognized medical value. Marinol was placed in Schedule II, the category for drugs with high abuse potential and liability to produce dependency, but certain recognized medical uses, after its FDA approval in 1985. Marinol was reassigned to Schedule III in 1999, a category denoting a lesser potential for abuse or lower dependency risk after documentation that little abuse or diversion (Calhoun et al 1998) had occurred. Nabilone was placed and has remained in Schedule II since 1985.

The degree to which a drug is reinforcing is determined partly by the by the rate of its delivery to the brain (Samaha and Robinson 2005). Sativex has effect onset in 15–40 minutes, peaking in a few hours, quite a bit slower than drugs of high abuse potential. It has been claimed that inclusion of CBD diminishes psychoactive effects of THC, and may lower potential drug abuse liability of the preparation (see Russo (2006b)) for discussion). Prior studies from Sativex clinical trials do not support the presence reinforcement or euphoria as problems in administration (Wade et al 2006).

Certain facets of acute cannabinoid exposure, including tachycardia, hypothermia, orthostatic hypotension, dry mouth, ocular injection, intraocular pressure decreases, etc. are subject to rapid tachyphylaxis upon continued administration (Jones et al 1976). No dose tolerance to the therapeutic effects of Sativex has been observed in clinical trials in over 1500 patient-years of administration. Additionally, therapeutic efficacy has been sustained for several years in a wide variety of symptoms; SAFEX studies in MS and peripheral neuropathic pain, confirm that Sativex doses remain stable or even decreased after prolonged usage (Wade et al 2006), with maintenance of therapeutic benefit and even continued improvement.

Debate continues as to the existence of a clinically significant cannabis withdrawal syndrome with proponents (Budney et al 2004), and questioners (Smith 2002). While withdrawal effects have been reported in recreational cannabis smokers (Solowij et al 2002), 24 volunteers with MS who abruptly stopped Sativex after more than a year of continuous usage displayed no withdrawal symptoms meeting Budney’s criteria. While symptoms recurred after 7–10 days of abstinence from Sativex, prior levels of symptom control were readily re-established upon re-titration of the agent (Wade et al 2006).

Overall, Sativex appears to pose less risk of dependency than smoked cannabis based on its slower onset, lower dosage utilized in therapy, almost total absence of intoxication in regular usage, and minimal withdrawal symptomatology even after chronic administration. No known abuse or diversion incidents have been reported with Sativex to date (as of November 2007). Sativex is expected to be placed in Schedule IV of the Misuse of Drugs Act in the United Kingdom once approved.

Cognitive effects of cannabis have been reviewed (Russo et al 2002; Fride and Russo 2006), but less study has occurred in therapeutic contexts. Effects of chronic heavy recreational cannabis usage on memory abate without sequelae after a few weeks of abstinence (Pope et al 2001). Studies of components of the Halstead-Reitan battery with Sativex in neuropathic pain with allodynia have revealed no changes vs placebo (Nurmikko et al 2007), and in central neuropathic pain in MS (Rog et al 2005), 4 of 5 tests showed no significant differences. While the Selective Reminding Test did not change significantly on Sativex, placebo patients displayed unexpected improvement.

Slight improvements were observed in Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales depression and anxiety scores were noted with Sativex in MS patients with central neuropathic pain (Rog et al 2005), although not quite statistically significant. No long-term mood disorders have been associated with Sativex administration.

Debate continues with regard to the relationship between cannabis usage and schizophrenia (reviewed (Fride and Russo 2006)). An etiological relationship is not supported by epidemiological data (Degenhardt et al 2003), but if present, should bear relation to dose and length of high exposure. It is likely that lower serum levels of Sativex in therapeutic usage, in conjunction with anti-psychotic properties of CBD (Zuardi and Guimaraes 1997), would minimize risks. Children and adolescents have been excluded from Sativex RCTs to date. SAFEX studies of Sativex have yielded few incidents of thought disorder, paranoia or related complaints.

Adverse effects of cannabinoids on immune function have been observed in experimental animals at doses 50–100 times the psychoactive level (Cabral 2001). In four patients using herbal cannabis therapeutically for over 20 years, no abnormalities were observed in leukocyte, CD4 or CD8 cell counts (Russo et al 2002). Investigation of MS patients on Cannador revealed no major immune changes (Katona et al 2005), and similarly, none occurred with smoked cannabis in a short-term study of HIV patients (Abrams et al 2003). Hematological measures have been normal in all Sativex RCTs without clinical signs of immune dysfunction.

Concerns are frequently noted with new drug-drug interactions, but few have resulted in Sativex RCTs despite its adjunctive use with opiates, many other psychoactive analgesic, antidepressant and anticonvulsant drugs (Russo 2006a), possibly due to CBD ability to counteract sedative effects of THC (Nicholson et al 2004). No effects of THC extract, CBD extract or Sativex were observed in a study of effects on the hepatic cytochrome P450 complex (Stott et al 2005b). On additional study, at 314 ng/ml cannabinoid concentration, Sativex and components produced no significant induction on human CYP450 (Stott et al 2007). Thus, Sativex should be safe to use in conjunction with other drugs metabolized via this pathway.

The Marinol patient monograph cautions that patients should not drive, operate machinery or engage in hazardous activities until accustomed to the drug’s effects (http://www.solvaypharmaceuticals-us.com/static/wma/pdf/1/3/1/9/Marinol5000124ERev52003.pdf). The Sativex product monograph in Canada (http://www.bayerhealth.ca/display.cfm?Object_ID=272&Article_ID=121&expandMenu_ID=53&prevSubItem=5_52) suggests that patients taking it should not drive automobiles. Given that THC is the most active component affecting such abilities, and the low serum levels produced in Sativex therapy (vide supra), it would be logical that that patients may be able to safely engage in such activities after early dose titration and according to individual circumstances, much as suggested for oral dronabinol. This is particularly the case in view of a report by an expert panel (Grotenhermen et al 2005) that comprehensively analyzed cannabinoids and driving. It suggested scientific standards such as roadside sobriety tests, and THC serum levels of 7–10 ng/mL or less, as reasonable approaches to determine relative impairment. No studies have demonstrated significant problems in relation to cannabis affecting driving skills at plasma levels below 5 ng/mL of THC. Prior studies document that 4 rapid oromucosal sprays of Sativex (greater than the average single dose employed in therapy) produced serum levels well below this threshold (Russo 2006b). Sativex is now well established as a cannabinoid agent with minimal psychotropic effect.

Cannabinoids may offer significant “side benefits” beyond analgesia. These include anti-emetic effects, well established with THC, but additionally demonstrated for CBD (Pertwee 2005), the ability of THC and CBD to produce apoptosis in malignant cells and inhibit cancer-induced angiogenesis (Kogan 2005; Ligresti et al 2006), as well as the neuroprotective antioxidant properties of the two substances (Hampson et al 1998), and improvements in symptomatic insomnia (Russo et al 2007).

The degree to which cannabinoid analgesics will be adopted into adjunctive pain management practices currently remains to be determined. Data on Sativex use in Canada for the last reported 6-month period (January-July 2007) indicated that 81% of prescriptions issued for patients in that interval were refills (data on file, from Brogan Inc Rx Dynamics), thus indicating in some degree an acceptance of, and a desire to, continue such treatment. Given their multi-modality effects upon various nociceptive pathways, their adjunctive side benefits, the efficacy and safety profiles to date of specific preparations in advanced clinical trials, and the complementary mechanisms and advantages of their combination with opioid therapy, the future for cannabinoid therapeutics appears very bright, indeed.

References

- ABC News, USA Today, Stanford Medical Center Poll. Broad experience with pain sparks search for relief [online] 2005 URL: http://abcnews.go.com/images/Politics/979a1TheFightAgainstPain.pdf.

- Abrams DI, Hilton JF, Leiser RJ, et al. Short-term effects of cannabinoids in patients with HIV-1 infection. A randomized, placbo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:258–66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-4-200308190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams DI, Jay CA, Shade SB, et al. Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:515–21. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000253187.66183.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal N, Pacher P, Tegeder I, et al. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type 1 cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:870–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. Cannabinoid (CB1) receptor activation inhibits trigeminovascular neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:64–71. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Kaube H, Goadsby PJ. Anandamide is able to inhibit trigeminal neurons using an in vivo model of trigeminovascular-mediated nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;309 :56–63. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Kaube H, Goadsby PJ. Anandamide acts as a vasodilator of dural blood vessels in vivo by activating TRPV1 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:1354–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attal N, Brasseur L, Guirimand D, et al. Are oral cannabinoids safe and effective in refractory neuropathic pain? Eur J Pain. 2004;8:173–7. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SP, Snyder SH, Mechoulam R. Cannabinoids: influence on neurotransmitter uptake in rat brain synaptosomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;194:74–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes MP. Sativex: clinical efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of symptoms of multiple sclerosis and neuropathic pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:607–15. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett ML, Scutt AM, Evans FJ. Cannflavin A and B, prenylated flavones from Cannabis sativa L. Experientia. 1986;42:452–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02118655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile AC, Sertie JA, Freitas PC, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of oleoresin from Brazilian Copaifera. J Ethnopharmacol. 1988;22:101–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu P. Effects of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, on postoperative pain: [Les effets de la nabilone, un cannabinoide synthetique, sur la douleur postoperatoire] Can J Anaesth. 2006;53:769–75. doi: 10.1007/BF03022793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlach DM, Shir Y, Ware MA. Experience with the synthetic cannabinoid nabilone in chronic noncancer pain. Pain Med. 2006;7:25–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JS, Symonds C, Birch R. Efficacy of two cannabis based medicinal extracts for relief of central neuropathic pain from brachial plexus avulsion: results of a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2004;112:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Hanus L, De Petrocellis L, et al. Molecular targets for cannabidiol and its synthetic analogues: effect on vanilloid VR1 receptors and on the cellular uptake and enzymatic hydrolysis of anandamide. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:845–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DR, Robson P, Ho M, Jubb RW, et al. Preliminary assessment of the efficacy, tolerability and safety of a cannabis-based medicine (Sativex) in the treatment of pain caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:50–2. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Medical Association. Therapeutic uses of cannabis. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997. p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Broom SL, Sufka KJ, Elsohly MA, et al. Analgesic and reinforcing proerties of delta9-THC-hemisuccinate in adjuvant-arthritic rats. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2001;1:171–82. [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, et al. Review of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1967–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggy DJ, Toogood L, Maric S, et al. Lack of analgesic efficacy of oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in postoperative pain. Pain. 2003;106:169–72. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein S, Levin E, Varanelli C. Prostaglandins and cannabis. II. Inhibition of biosynthesis by the naturally occurring cannabinoids. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:2905–10. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral G. Immune system. In: Russo EB, Grotenhermen F, editors. Cannabis and cannabinoids: Pharmacology, toxicology and therapeutic potential. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 2001. pp. 279–87. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun SR, Galloway GP, Smith DE. Abuse potential of dronabinol (Marinol) J Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30:187–96. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Tramber MR, Carroll D, et al. Are cannabinoids an effective and safe option in the management of pain? A qualitative systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier EJ, Auchampach JA, Hillard CJ. Inhibition of an equilibrative nucleoside transporter by cannabidiol: a mechanism of cannabinoid immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7895–900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511232103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challapalli PV, Stinchcomb AL. In vitro experiment optimization for measuring tetrahydrocannabinol skin permeation. Int J Pharm. 2002;241:329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichewicz DL, Martin ZL, Smith FL, et al. Enhancement of mu opioid antinociception by oral delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol: Dose-response analysis and receptor identification. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:859–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichewicz DL, McCarthy EA. Antinociceptive synergy between delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and opioids after oral administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1010–5. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.045575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichewicz DL, Welch SP. Modulation of oral morphine antinociceptive tolerance and naloxone-precipitated withdrawal signs by oral Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:812–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark P, Altman D. Assessment of blinding in Phase III Sativex spasticity studies. GW Pharmaceuticals; 2006. p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Clermont-Gnamien S, Atlani S, Attal N, et al. Utilisation thérapeutique du delta-9-tétrahydrocannabinol (dronabinol) dans les douleurs neuropathiques réfractaires. [The therapeutic use of D9-tetrahydrocannabinol (dronabinol) in refractory neuropathic pain] Presse Med. 2002;31(39 Pt 1):1840–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis WM, Hatoum NS. Neurobehavioral actions of cannabichromene and interactions with delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Gen Pharmacol. 1983;14:247–52. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(83)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Meijer E. The breeding of cannabis cultivars for pharmaceutical end uses. In: Guy GW, Whittle BA, Robson P, editors. Medicinal uses of cannabis and cannabinoids. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2004. pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Testing hypotheses about the relationship between cannabis use and psychosis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:37–48. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Melck D, Bisogno T, et al. Endocannabinoids: endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligands with neuromodulatory action. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:521–8. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogrul A, Gul H, Akar A, et al. Topical cannabinoid antinociception: synergy with spinal sites. Pain. 2003;105:11–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson A, Peacock M, Chen A, et al. Antihyperalgesic properties of the cannabinoid CT-3 in chronic neuropathic and inflammatory pain states in the rat. Pain. 2005;116:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElSohly MA, Ross SA, Mehmedic Z, et al. Potency trends of delta9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated marijuana from 1980–1997. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst G, Denke C, Reif M, et al. Standardized cannabis extract in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study; International Association for Cannabis as Medicine; 2005 September 9; Leiden, Netherlands. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Evans FJ. Cannabinoids: The separation of central from peripheral effects on a structural basis. Planta Med. 1991;57:S60–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimiani C, Liberty T, Aquirre AJ, et al. Opiate, cannabinoid, and eicosanoid signaling converges on common intracellular pathways nitric oxide coupling. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 1999;57:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(98)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman SM. Pain and politics: DEA, Congress, and the courts, oh my! Pain Med. 2006;7:87–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald GA. Coxibs and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1709–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration; Services UDoHaH. Guidance for industry: Botanical drug products. US Government; 2004. p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Fox A, Kesingland A, Gentry C, et al. The role of central and peripheral Cannabinoid1 receptors in the antihyperalgesic activity of cannabinoids in a model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2001;92:91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E, Russo EB. Neuropsychiatry: Schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety. In: Onaivi E, Sugiura T, Di Marzo V, editors. Endocannabinoids: The brain and body’s marijuana and beyond. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis; 2006. pp. 371–82. [Google Scholar]

- Frondini C, Lanfranchi G, Minardi M, et al. Affective, behavior and cognitive disorders in the elderly with chronic musculoskelatal pain: the impact on an aging population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;44(Suppl 1):167–71. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. Isolation, structure and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:1646–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gauson LA, Stevenson LA, Thomas A, et al. 17th Annual Symposium on the Cannabinoids. Saint-Sauveur, Quebec, Canada: International Cannabinoid Research Society; 2007. Cannabigerol behaves as a partial agonist at both CB1 and CB2 receptors; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen ME, Carley WW, Ranges GE, et al. Flavonoids inhibit cytokine-induced endothelial cell adhesion protein gene expression. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:278–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertsch J, Raduner S, Leonti M, et al. 17th Annual Symposium on the Cannabinoids. Saint-Sauveur, Quebec, Canada: International Cannabinoid Research Society; 2007. Screening of plant extracts for new CB2-selective agonists revewals new players in Cannabis sativa; p. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson SJ. IASP global year against pain in older persons: highlighting the current status and future perspectives in geriatric pain. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:627–35. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.6.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieringer D, St Laurent J, Goodrich S. Cannabis vaporizer combines efficient delivery of THC with effective suppression of pyrolytic compounds. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2004;4:7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gil ML, Jimenez J, Ocete MA, et al. Comparative study of different essential oils of Bupleurum gibraltaricum Lamarck. Pharmazie. 1989;44:284–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MA, Saenz MT, Garcia MD, et al. Study of the topical anti-inflammatory activity of Achillea ageratum on chronic and acute inflammation models. Z Naturforsch [C] 1999;54:937–41. doi: 10.1515/znc-1999-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter RW, Butorac M, Cobian EP, et al. Medical use of cannabis in the Netherlands. Neurology. 2005;64:917–9. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152845.09088.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB. Marihuana, the forbidden medicine. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1997. pp. xv–296. [Google Scholar]

- Grotenhermen F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:327–60. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotenhermen F. Cannabinoids for therapeutic use: designing systems to increase efficacy and reliability. American Journal of Drug Delivery. 2004;2:229–40. [Google Scholar]

- Grotenhermen F, Leson G, Berghaus G, et al. Findings and recommendations by an expert panel. Hürth, Germany: Nova- Institut; 2005. Developing science-based per se limits for driving under the influence of cannabis (DUIC) p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Guy GW, Robson P. A Phase I, double blind, three-way crossover study to assess the pharmacokinetic profile of cannabis based medicine extract (CBME) administered sublingually in variant cannabinoid ratios in normal healthy male volunteers (GWPK02125) Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2003;3:121–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson AJ, Grimaldi M, Axelrod J, et al. Cannabidiol and (-)Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8268–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazekamp A, Ruhaak R, Zuurman L, et al. Evaluation of a vaporizing device (Volcano) for the pulmonary administration of tetrahydrocannabinol. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95:1308–17. doi: 10.1002/jps.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, et al. Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1932–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Briley EM, Herkenham M. Pre- and postsynaptic distribution of cannabinoid and mu opioid receptors in rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1999;822:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Martin WJ, Tsou K, et al. Inhibition of noxious stimulus-evoked activity of spinal cord dorsal horn neurons by the cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2. Life Sci. 1995;56:2111–8. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00196-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Suplita RL, Bolton NM, et al. An endocannabinoid mechanism for stress-induced analgesia. Nature. 2005;435:1108–12. doi: 10.1038/nature03658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdcroft A, Maze M, Dore C, et al. A multicenter dose-escalation study of the analgesic and adverse effects of an oral cannabis extract (Cannador) for postoperative pain management. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1040–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200605000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, et al. Nonclassical cannabinoid analgetics inhibit adenylate cyclase: development of a cannabinoid receptor model. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;33:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ. Blood cannabinoids. I. Absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. J Anal Toxicol. 1992;16:276–82. doi: 10.1093/jat/16.5.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse AFC, Breekveldt-Postma NS, Erkens JA, et al. Medicinal gebruik van cannabis.: PHARMO Instituut [Institute for Drug Outcomes Research] 2004:51. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JR, Potts R. Cannabis-based medicines in the treatment of cancer pain: a randomised, double-blind, parallel group, placebo controlled, comparative study of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of Sativex and Tetranabinex in patients with cancer-related pain. Edinburgh, Scotland: 2005. Mar, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RT, Benowitz N, Bachman J. Clinical studies of cannabis tolerance and dependence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;282:221–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb49901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy JE, Watson SJ, Benson JA., Jr . Marijuana and medicine: Assessing the science base. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsak M, Gaffal E, Date R, et al. Attenuation of allergic contact dermatitis through the endocannabinoid system. Science. 2007;316:1494–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1142265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst M, Salim K, Burstein S, et al. Analgesic effect of the synthetic cannabinoid CT-3 on chronic neuropathic pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1757–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona S, Kaminski E, Sanders H, et al. Cannabinoid influence on cytokine profile in multiple sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:580–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA, Carpentier C, Griffiths P. Cannabis potency in Europe. Addiction. 2005;100:884–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.001137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko MC, Woods JH. Local administration of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol attenuates capsaicin-induced thermal nociception in rhesus monkeys: a peripheral cannabinoid action. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;143:322–6. doi: 10.1007/s002130050955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan NM. Cannabinoids and cancer. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5:941–52. doi: 10.2174/138955705774329555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberger L, Rubin A, Wolen R, et al. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism and drug-abuse potential of nabilone. Cancer Treat Rev. 1982;9(Suppl B):17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(82)80031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Daughters RS, Bullis C, et al. The cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 mesylate blocks the development of hyperalgesia produced by capsaicin in rats. Pain. 1999;81:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligresti A, Moriello AS, Starowicz K, et al. Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:1375–87. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Li H, Burstein SH, Zurier RB, et al. Activation and binding of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma by synthetic cannabinoid ajulemic acid. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:983–92. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti BB, Souza GE, Sarti SJ, et al. Myrcene mimics the peripheral analgesic activity of lemongrass tea. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;34:43–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90187-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch ME, Young J, Clark AJ. A case series of patients using medicinal marihuana for management of chronic pain under the Canadian Marihuana Medical Access Regulations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K. Cannabinoid receptors as therapeutic targets. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:101–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maida V. The synthetic cannabinoid nabilone improves pain and symptom management in cancer patietns. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103:121–2. [Google Scholar]

- Malfait AM, Gallily R, Sumariwalla PF, et al. The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9561–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160105897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanares J, Corchero J, Romero J, et al. Chronic administration of cannabinoids regulates proenkephalin mRNA levels in selected regions of the rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;55:126–32. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, Hohmann AG, Walker JM. Suppression of noxious stimulus-evoked activity in the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus by a cannabinoid agonist: Correlation between electrophysiological and antinociceptive effects. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6601–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06601.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa F, Monory K. Endocannabinoids and the gastrointestinal tract. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29(3 Suppl):47–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPartland JM, Russo EB. Cannabis and cannabis extracts: Greater than the sum of their parts? Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2001;1:103–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmedic Z, Martin J, Foster S, et al. Delta-9-THC and other cannabinoids content of confiscated marijuana: potency trends, 1993-2003. International Association of Cannabis as Medicine; 2005 September 10; Leiden, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Vahl KR, Schneider U, Kolbe H, et al. Treatment of Tourette’s syndrome with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–5. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadulski T, Pragst F, Weinberg G, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study about the effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on the pharmacokinetics of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) after oral application of THC verses standardized cannabis extract. Ther Drug Monit. 2005a;27:799–810. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000177223.19294.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadulski T, Sporkert F, Schnelle M, et al. Simultaneous and sensitive analysis of THC, 11-OH-THC, THC-COOH, CBD, and CBN by GC-MS in plasma after oral application of small doses of THC and cannabis extract. J Anal Toxicol. 2005b;29:782–9. doi: 10.1093/jat/29.8.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff GW, O’Brien CB, Reddy KR, et al. Preliminary observation with dronabinol in patients with intractable pruritus secondary to cholestatic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2117–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AN, Turner C, Stone BM, et al. Effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on nocturnal sleep and early-morning behavior in young adults. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:305–13. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000125688.05091.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolodi M, Volpe AR, Sicuteri F. Fibromyalgia and headache. Failure of serotonergic analgesia and N-methyl-D-aspartate-mediated neuronal plasticity: Their common clues. Cephalalgia. 1998;18(Suppl 21):41–4. doi: 10.1177/0333102498018s2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notcutt W, Price M, Chapman G. Clinical experience with nabilone for chronic pain. Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1997;3:551–5. [Google Scholar]

- Notcutt W, Price M, Miller R, et al. Initial experiences with medicinal extracts of cannabis for chronic pain: results from 34 “N of 1” studies. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:440–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurmikko TJ, Serpell MG, Hoggart B, et al. Sativex successfully treats neuropathic pain characterised by allodynia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.028. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Batkai S, Kunos G. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:389–462. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate D. Chemical ecology of cannabis. Journal of the International Hemp Association. 1994;2:32–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez J. Combined cannabinoid therapy via na oromucosal spray. Drugs Today (Barc) 2006;42:495–501. doi: 10.1358/dot.2006.42.8.1021517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Cannabidiol as a potential medicine. In: Mechoulam R ed. Cannabinoids as therapeutics. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser Verlag; 2005. pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Gruber AJ, Hudson JI, et al. Neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:909–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn EJ, Makriyannis A, Hohmann AG. Activation of cannabinoid CB(1) and CB(2) receptors suppresses neuropathic nociception evoked by the chemotherapeutic agent vincristine in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2007:1–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VS, Menezes AM, Viana GS. Effect of myrcene on nociception in mice. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1990;42:877–8. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb07046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re L, Barocci S, Sonnino S, et al. Linalool modifies the nicotinic receptor-ion channel kinetics at the mouse neuromuscular junction. Pharmacol Res. 2000;42:177–82. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Aanonsen L, Hargreaves KM. SR 141716A, a cannabinoid receptor antagonist, produces hyperalgesia in untreated mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;319:R3–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00952-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Aanonsen L, Hargreaves KM. Antihyperalgesic effects of spinal cannabinoids. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998a;345:145–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Aanonsen L, Hargreaves KM. Hypoactivity of the spinal cannabinoid system results in NMDA-dependent hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 1998b;18:451–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00451.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JD, Kilo S, Hargreaves KM. Cannabinoids reduce hyperalgesia and inflammation via interaction with peripheral CB1 receptors. Pain. 1998c;75:111–9. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rog DJ, Nurmiko T, Friede T, et al. Randomized controlled trial of cannabis based medicine in central neuropathic pain due to multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;65:812–19. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176753.45410.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo E. Cannabis for migraine treatment: The once and future prescription? An historical and scientific review. Pain. 1998;76:3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB. Hemp for headache: An in-depth historical and scientific review of cannabis in migraine treatment. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2001;1:21–92. [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB. Clinical endocannabinoid deficiency (CECD): Can this concept explain therapeutic benefits of cannabis in migraine, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome and other treatment-resistant conditions? Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2004;25:31–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB. The role of cannabis and cannabinoids in pain management. In: Cole BE, Boswell M, editors. Weiner’s Pain Management: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. 7. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2006a. pp. 823–44. [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB. The solution to the medicinal cannabis problem. In: Schatman ME, editor. Ethical issues in chronic pain management. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis; 2006b. pp. 165–194. [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB, Guy GW. A tale of two cannabinoids: the therapeutic rationale for combining tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66:234–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB, Guy GW, Robson PJ. Cannabis, pain and sleep: lessons from therapeutic clinical trials of Sativex® cannabis based medicine. Chem Biodivers. 2007a;4:1729–43. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB, Mathre ML, Byrne A, et al. Chronic cannabis use in the Compassionate Investigational New Drug Program: An examination of benefits and adverse effects of legal clinical cannabis. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2002;2:3–57. [Google Scholar]

- Samaha AN, Robinson TE. Why does the rapid delivery of drugs to the brain promote addiction? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:82–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarchielli P, Pini LA, Coppola F, et al. Endocannabinoids in chronic migraine: CSF findings suggest a system failure. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1384–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer CF, Brackett DJ, Gunn CG, et al. Decreased platelet aggregation following marihuana smoking in man. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1979;72:435–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schley M, Legler A, Skopp G, et al. Delta-9-THC based monotherapy in fibromyalgia patients on experimentally induced pain, axon reflex flare, and pain relief. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1269–76. doi: 10.1185/030079906x112651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M, Piser TM, Seybold VS, et al. Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit glutamatergic synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal cultures. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4322–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NT. A review of the published literature into cannabis withdrawal symptoms in human users. Addiction. 2002;97:621–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solowij N, Stephens RS, Roffman RA, et al. Cognitive functioning of long-term heavy cannabis users seeking treatment. JAMA. 2002;287:1123–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadone C. Neurophysiologie du cannabis [Neurophysiology of cannabis] Encephale. 1991;17:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott CG, Ayerakwa L, Wright S, et al. 17th Annual Symposium on the Cannabinoids. Saint-Sauveur, Quebec, Canada: International Cannabinoid Research Society; 2007. Lack of human cytochrome P450 induction by Sativex; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Stott CG, Guy GW, Wright S, et al. The effects of cannabis extracts Tetranabinex and Nabidiolex on human cyclo-oxygenase (COX) activity. International Cannabinoid Research Society; June 2005; Clearwater, FL. 2005a. [Google Scholar]

- Stott CG, Guy GW, Wright S, et al. The effects of cannabis extracts Tetranabinex and Nabidiolex on human cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism. International Cannabinoid Research Association; June 27 2005; Clearwater, FL. 2005b. p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Strangman NM, Walker JM. Cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 inhibits the activity-dependent facilitation of spinal nociceptive responses. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:472–7. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen KB, Jensen TS, Bach FW. Does the cannabinoid dronabinol reduce central pain in multiple sclerosis? Randomised double blind placebo controlled crossover trial. BMJ. 2004;329:253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38149.566979.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambe Y, Tsujiuchi H, Honda G, et al. Gastric cytoprotection of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory sesquiterpene, beta-caryophyllene. Planta Med. 1996;62:469–70. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP. Smoked marijuana as a cause of lung injury. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2005;63:93–100. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2005.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topol EJ. Failing the public health ’ rofecoxib, Merck, and the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1707–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volfe Z, Dvilansky A, Nathan I. Cannabinoids block release of serotonin from platelets induced by plasma from migraine patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1985;5:243–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade DT, Makela P, Robson P, et al. Do cannabis-based medicinal extracts have general or specific effects on symptoms in multiple sclerosis? A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study on 160 patients. Mult Scler. 2004;10:434–41. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1082oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade DT, Makela PM, House H, et al. Long-term use of a cannabis-based medicine in the treatment of spasticity and other symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12:639–45. doi: 10.1177/1352458505070618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade DT, Robson P, House H, et al. A preliminary controlled study to determine whether whole-plant cannabis extracts can improve intractable neurogenic symptoms. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:18–26. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr581oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JM, Hohmann AG, Martin WJ, et al. The neurobiology of cannabinoid analgesia. Life Sci. 1999a;65:665–73. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JM, Huang SM, Strangman NM, et al. Pain modulation by the release of the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999b;96:12198–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JM, Huang SM. Cannabinoid analgesia. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;95:127–35. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]