Abstract

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in cancer patients places a significant burden on patients’ function and quality of life, their families and caregivers, and healthcare providers. Despite the advances in preventing CINV, a substantial proportion of patients experience persistent nausea and vomiting. Nabilone, a cannabinoid, recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of the nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy who fail to achieve adequate relief from conventional treatments. The cannabinoids exert antiemetic effects via agonism of cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2). Clinical trials have demonstrated the benefits of nabilone in cancer chemotherapy patients. Use of the agent is optimized with judicious dosing and selection of patients.

Keywords: nabilone, chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting, pain

The burden of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

In the absence of preventive therapy, 70%–80% of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy experience associated nausea and vomiting (Morran et al 1979; Jenns 1994). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and its side effects imposes a burden on patients, clinicians, and the healthcare system (Vanscoy et al 2005; Wiser and Berger 2005). Of all the side effects of chemotherapy, CINV remains one of the most dreaded by patients (Sun et al 2004). Patients report a substantial negative impact of CINV on their ability to complete activities of daily living, obtain adequate rest, participate in social activities, and perform work (Lee et al 2005; Wiser and Berger 2005). Further, CINV can have deleterious physiologic effects, including metabolic derangements, malnutrition, and esophageal tears, among others (Wiser and Berger 2005; National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2006). In up to 30% of patients, CINV is so distressing that consideration is given to discontinuing treatment, which underscores the need for effective control of the nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy (Wiser and Berger 2005).

The introduction of 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists has had a dramatic effect on preventing CINV in cancer patients (Abrahm 2005). With clinical experience, however, it has become apparent that while these agents are effective for controlling acute CINV, they are ineffective agents for delayed nausea (Hickok et al 2003; Kris et al 2006). The substance P/neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonist, aprepitant, augments the antiemetic action of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and corticosteroids such as dexamethasone. The most effective way of controlling delayed nausea and vomiting is to prevent the acute phase; as such, the addition of aprepitant to antiemetic regimens has assisted clinicians in controlling both acute and delayed CINV (Schwartzberg 2006). The recently revised American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Guidelines, as well as those from the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC), reflect the efficacy of aprepitant for prevention of delayed CINV due to highly emetogenic chemotherapy, recommending its use with a corticosteroid and against the use of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for this purpose (Gralla 2005; Kris et al 2006).

Despite the augmentation of antiemetic activity provided by aprepitant, a substantial proportion of patients receiving first-line therapy continue to experience persistent delayed CINV. Poli-Bigelli and colleagues reported their efficacy findings from a clinical trial involving 523 evaluable subjects who were receiving high-dose cisplatin-based chemotherapy (Poli-Bigelli et al 2005). Compared with standard therapy (5-HT3 receptor antagonist and a corticosteroid), the aprepitant-containing regimen (combined with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and a corticosteroid) was significantly (p < 0.001) more effective in achieving complete control, defined as no emesis and no rescue therapy. The investigators’ secondary analyses revealed persistent delayed nausea in nearly half (47%) of the patients, however, and significant delayed nausea in more than one of every four patients. Delayed emesis occurred in 28% of patients. Overall, total control was documented in less than half (44%) of patients.

Anticipatory nausea and vomiting also represents a significant problem among cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Although the etiology is likely to be multifactorial, one major cause is thought to be classic or Pavlovian conditioning (Stockhorst et al 1993) due to incomplete control of post-treatment nausea (Morrow et al 1998). Anticipatory nausea occurs in 29% of chemotherapy patients, and anticipatory vomiting occurs in 11% of patients about to undergo chemotherapy (Morrow et al 1998; Roscoe et al 2000). Despite improvements in overall CINV with the introduction of 5-HT3 receptor antagonist medications, the incidence of anticipatory nausea and vomiting has remained the same (Morrow et al 1998).

The high prevalence of CINV in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, the burden imposed on patients, and the failure of first-line and conventional antiemetic therapies to provide adequate control of nausea and vomiting, particularly delayed events, indicate an ongoing need for additional treatment options. Combining agents with different mechanisms of action (MOA) may be the optimal approach to management of CINV (National Cancer Institute 2006).

The use of cannabis to self-treat CINV has been known for several years (Vinciguerra et al 1988), and with recent improvements in our understanding of the physiology underlying cannabis effects, renewed efforts are underway to identify safe and effective pharmaceutical cannabinoids. A recent systematic review found evidence that cannabinoids were a rational option for CINV (Tramér et al 2001). This paper examines the clinical evidence for nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid recently approved in the United States for the treatment of CINV.

Scientific rationale for the use of the cannabinoids in CINV

Since the definitive identification of cannabinoid (CB) receptors in humans, a better understanding of the science behind the effects of exogenous cannabinoids has emerged. Two CB receptors have been identified in humans (CB1 and CB2) which are recognized exclusively by cannabinoids. (Howlett et al 2002; Martin and Wiley 2004). The CB1 receptor is present in high densities in areas of the central nervous system (CNS), and it is the interaction between nabilone and this receptor and its signaling pathways that appears to be responsible for the antiemetic effects of the agent. Endocannabinoids – endogenous cannabinoid ligands that act on CB receptors – exert complex effects, including the modulation of neurotransmitters known to be involved in CINV (Howlett et al 2002; Martin and Wiley 2004). More specifically, endocannabinoids activate the pre-synaptic CB1 receptor, inhibiting release of both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in the CNS and peripheral nervous system (ie, glutamate and gamma aminobutyric acid [GABA], respectively) (Schlicker and Kathmann 2001; Howlett et al 2002). The effect of endocannabinoids is not solely inhibitory in nature; however, as an initial inhibitory effect may trigger increased release of neurotransmitters further along the pathway, thus inhibitory and excitatory effects may be observed.

The antiemetic effects of the endocannabinoid system appear to be produced by a multi-step process in which the CB1 ligands act as retrograde synaptic messengers (Diana and Mart 2004). In this “reverse signaling” process, neurotransmitters released from the pre-synaptic neuron activate the post-synaptic receptors. In turn, the activated post-synaptic neuron releases endocannabinoids such as anandamide (Freund et al 2003; Navari 2003; Piomelli 2003) These endogenous CB1 ligands then diffuse back and bind to the pre-synaptic CB1 receptor (Piomelli 2003). Binding of endocannabinoids to the CB1 receptor results in activation of a G-protein leading to a reduction of neurotransmitter release, a process known as depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI) (Freund et al 2003; Diana and Mart 2004)

Several neurotransmitters mediate nausea and vomiting, including serotonin, dopamine, GABA, glutamate, cannabinoids, and others (Andrews et al 1998; Lynch 2005). Antagonism of serotonin, dopamine, and substance P receptors (5-HT3 , D2, and NK1, respectively) produces clinically meaningful antiemetic effects. In contrast, it is the agonism of CB1 receptors, such as that produced by cannabinoid compounds, which results in antiemetic effects. CB agonist drugs circumvent the multi-step process of the endogenous system (Figure 1) (Croxford 2003; Navari 2003; Freund et al 2003; Piomelli 2003; Diana and Mart 2004). In addition to modulatory effects on CB receptors, the CB1 agonist nabilone may also indirectly and partially manipulate 5-HT3 and D2 receptors (Ward and Holmes 1985; Nahas et al 2002).

Figure 1.

The mechanism of action of cannabinoids. The innate cannabinoid system inhibits release of neurotransmitters via a multi-step retrograde signaling pathway. Nabilone mimics the action of endocannabinoids via direct activation of CB1 receptors (derived from Croxford 2003; Freund et al 2003; Navari 2003; Piomelli 2003; Diana and Mart 2004).

Abbreviations: THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

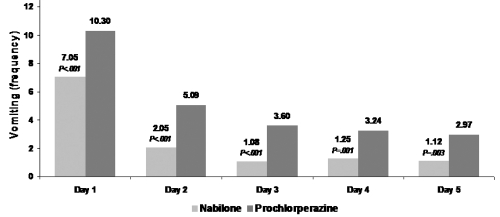

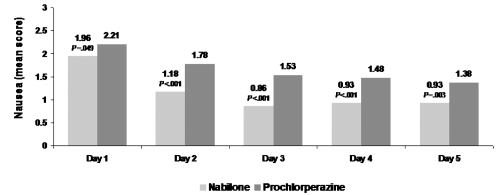

Figure 2.

a Nabilone reduces frequency of vomiting on chemotherapy days 1 through 5. Reproduced with permission from Einhorn LH, Nagy C, Furnas B, Williams SD. 1981. Nabilone: An effective antiemetic in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol, 21(suppl):64–69. Copyright © 1981 SAGE Publications.

b Nabilone significantly reduces the severity of nausea throughout the chemotherapy cycle. Reproduced with permission from Einhorn LH, Nagy C, Furnas B, Williams SD. 1981. Nabilone: An effective antiemetic in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol, 21(suppl):64–69. Copyright © 1981 SAGE Publications.

Grading of nausea: 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe.

Specific areas of the brain are involved in emesis and nausea, including the dorsal vagal complex, particularly the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) within this complex. Neurons in the area postrema, which is often referred to as the chemoreceptor trigger zone, transmit messages regarding such blood-borne emetics as cytotoxic drugs to the NTS. The NTS also receives messages regarding abdominal irritants through vagal afferents. In turn, NTS neurons transmit these messages to the brainstem, which directs emetic behavior (Hornby 2001). Other areas of the brain involved in CINV are the higher cortical and limbic regions, where the senses of taste, smell, sight, and memory are modulated. Through descending connections with the brainstem emetic center, these regions can influence stimulation or suppression of nausea and vomiting, including anticipatory nausea and vomiting (Grunberg 1989; Fride et al 2005). CB1 receptors are present in vast quantities in the CNS, exceeding levels of nearly all neurotransmitter receptors, and in nearly every brain region, including those involved in the pathophysiology of CINV (Martin and Wiley 2004). CB1 receptors are therefore valid targets for antiemetic effects in patients with CINV.

Anticipatory nausea and vomiting is a learned response to chemotherapy that develops only after poor initial control of CINV. Studies have shown that anticipatory nausea and vomiting follows the theory of a Pavlovian conditioned reflex; the thought of chemotherapy or other elements associated with it is the stimulus (Stockhorst et al 1993). The risk of developing this problem increases with the number of cycles received and may persist for some time after the completion of therapy (Aapro et al 2005). Anxiety may play a role in this condition (Morrow et al 1998), and two randomized trials have shown efficacy using benzodiazepines when added to psychological support programs (Razavi et al 1993; Malik et al 1995). Interestingly, the synthetic cannabinoid nabilone has been found to be effective in anxiety (Fabre and McLendon 1981). An animal model of anticipatory nausea and vomiting has been developed for the testing of cannabinoids (Parker and Kemp 2001; Limebeer et al 2006), which has shown cannabinoids to be effective in anticipatory nausea, significantly better than both placebo and ondansetron (Parker and Kemp 2006).

Efficacy and safety of nabilone

Nabilone is a synthetic cannabinoid developed in the 1970’s (Lemberger and Rowe 1975) which is a potent CB1 agonist. Results from early clinical studies demonstrated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of nabilone in reducing the frequency of vomiting and lessening the severity of nausea in cancer patients with CINV (Herman et al 1977, 1979; Einhorn et al 1981). In patients (n = 13) with CINV unrelieved by prochlorperazine, nabilone reduced vomiting frequency and nausea severity in 77%; more than half of the patients experienced “excellent response” to therapy or complete resolution of CINV (Herman et al 1977). In this study, patients were given either 1 mg or 2 mg nabilone every 8 hours. A more potent antiemetic effect was observed with the higher dose. Generally, the commonly occurring side effects – sedation, dry mouth, dizziness, and some decrease in coordination – as well as those that occurred less often, were mild or moderate in severity. More than one half of the patients reported an increase in appetite and food intake.

A second paper by the same authors reported on two double-blind, crossover trials conducted in a total of 113 evaluable patients with severe CINV (Herman et al 1979). During chemotherapy cycle 1, patients received either 2 mg nabilone or 10 mg prochlorperazine every 8 hours. The patients crossed over to the second drug regimen during the second cycle. All patients received 2 doses of antiemetic medication before chemotherapy for both cycles. Nabilone was more effective for providing complete relief of nausea and vomiting than was prochlorperazine (8% vs 0%), and significantly (p < 0.01) more effective for providing a partial response (72% vs 32%). The number of partial and complete responses occurring with nabilone was significantly (p < 0.001) greater than that with prochlorperazine (80% vs 32%). The response to nabilone in terms of reduced vomiting was greater on all 5 days of therapy when compared with prochlorperazine (p < 0.001), and nausea severity declined each day patients received nabilone. The efficacy of nabilone was observed with all types of chemotherapy and regardless of which order patients received the agent. Nine patients discontinued antiemetic therapy due to development of intolerable side effects – 4 who were receiving prochlorperazine and 5 during nabilone therapy. The predominant side effects were similar with both drugs; however, the incidence was approximately doubled during nabilone therapy. Nonetheless, a significant (p < 0.001) proportion of patients preferred nabilone over prochlorperazine (78% vs 15%).

Einhorn and colleagues conducted a double-blind, randomized, cross-over study in 100 cancer patients (Einhorn et al 1981). These patients, most of whom received cisplatin-based chemotherapy for testicular cancer, received 2 mg nabilone or 10 mg prochlorperazine every 6 hours as needed during chemotherapy cycle one and crossed over to the second drug during cycle 2. Compared with the effects of prochlorperazine, nabilone significantly (p < 0.001) reduced the severity and duration of nausea and frequency of vomiting. In patients receiving nabilone, the mean severity score for nausea (1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe nausea) declined from day 1 to day 3 and remained stable thereafter at values lower than 1. With nabilone therapy, the number of vomiting episodes was reduced by about 33% on all days of chemotherapy. Of the 20 patients who failed to complete the study, only 3 withdrew due to adverse effects of nabilone. Similar to the finding from Herman and associates, patients overwhelmingly preferred nabilone over prochlorperazine (60 patients [75%] vs 17 patients [17%]). Of the 60 patients who indicated a preference for nabilone, 46 received further chemotherapy and opted to continue to receive nabilone for a total of 76 courses of chemotherapy.

Results similar to those described above have also been found showing the superiority of nabilone compared to prochlorperazine in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (Ahmedazi et al 1983; Niiranen and Mattson 1985), but the side effect profile of dizziness and disorientation demands careful patient monitoring. No difference was found between nabilone and metoclopramide in patients on cisplatin (Crawford and Buckman 1986), while nabilone has been found superior to alizapride in young patients with testicular cancer on cisplatin (Niederle 1986) and was superior to domperidone in another trial in which 70% of subjects were on cisplatin (Pomeroy et al 1986). Mixed results have been found comparing oral nabilone and prochlorperazine to intravenous dexamethasone and metoclopramide (Cunningham et al 1988). Nabilone has even shown to be superior to prochlorperazine for children undergoing chemotherapy (Chan et al 1987). The effectiveness and tolerability of nabilone may be improved by the addition of dexamethasone (Niiranen and Mattson 1987).

The results of these early studies were summarized in a 2001 systematic review of 30 studies involving cannabinoids (nabilone, 16 studies; dronabinol, 13 studies; levonantradol, 1 study) compared with placebo or active control (prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, domperidone, and alizapride) for the treatment of CINV (Tramér et al 2001). Cannabinoids were more effective than either active control or placebo for the reduction of vomiting episodes and lessening of nausea severity. When compared with placebo (4 studies), the number needed to treat (NNT) for complete control of nausea was 8; compared with active control (7 studies), the NNT was 6.4. Compared with placebo (4 studies) and active control (6 studies), the NNT for complete control of vomiting was 3.3 and 8, respectively. Cannabinoids were shown to be well tolerated, and analysis demonstrated a patient preference for these agents over both active controls and placebo. As well, the authors commented that “In selected patients, cannabinoids may be useful as mood enhancing adjuvants for the control of chemotherapy related sickness”, likely referring to the possible benefits in patients with anticipatory nausea and vomiting (Tramér et al 2001).

Since these studies were conducted, the 5-HT3 and NK receptor antagonists have been developed and incorporated into routine clinical care protocols. Studies comparing nabilone to these agents either alone or in combination have not been done to date. Dronabinol, a synthetic form of tetrahydrocannabinol (the principle psychoactive ingredient in cannabis) has also been licensed as an antiemetic and has not been shown to be superior to ondansetron (Meiri et al 2007). Head-to-head comparative studies are needed to determine the possible clinical and cost benefits of cannabinoid therapy.

Nabilone has recently been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy in cancer patients who fail to respond adequately to conventional antiemetic treatments (Waknine 2006). Nabilone is typically given twice daily owing to its long duration of action (8–12 hours). The usual daily dosage of nabilone is 1–2 mg bid, with the first dose given 1–3 hours before administration of chemotherapy; the maximum recommended daily dosage is 6 mg daily divided bid or tid. Similar to several medications, there is a therapeutic window for nabilone, at which maximum benefit is obtained without intolerable side effects. Thus, treatment should be initiated with the lowest starting dose, and the dose should be increased based on patient response to minimize side effects. Patients often benefit from one dose the evening before chemotherapy, and another dose 1 to 3 hours pre-chemotherapy.

The most commonly occurring side effects of nabilone therapy are drowsiness, vertigo, dry mouth, euphoria, ataxia, headache, and concentration difficulties. Generally, the side effects are mild in intensity and temporary in duration. Tolerance to the CNS effects of nabilone, such as drowsiness and vertigo, develops rapidly. Assessing patients prior to initiating therapy can assist in reducing side effects and increasing tolerability. Patients should be warned about taking nabilone with alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, or other psychoactive substances due to the potential for augmentation of CNS effects. Nabilone should be used with caution in patients with current or past history of psychiatric disorders, as well as those with a history of substance abuse. Both short- and long-term cognitive effects of cannabinoids are not well described under therapeutic conditions, but based on the well-known cognitive effects of recreational cannabis use, careful monitoring is advised. Severe cognitive impairment from therapeutic use of nabilone has not been described. The response to and tolerance of nabilone varies from individual to individual; thus, patients should remain under the supervision of a responsible adult during initial use of the medication. Drug–drug interactions may be a concern in cancer patients who might be taking several different medications concurrently. Nabilone does not induce cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzymes and lacks significant 3A4 inhibitory effect (Nahas et al 2002). Thus, interactions with drugs metabolized via this pathway, such as macrolide antibiotics, calcium channel blockers, and others, are unlikely.

In summary, results from early clinical trials demonstrated the efficacy of nabilone in reducing the frequency of vomiting and lessening the severity of nausea in cancer patients with severe and/or refractory CINV. Importantly, nabilone was effective across the 5 days of chemotherapy in reducing both vomiting episodes and nausea severity, specific areas in which other antiemetic agents fail to provide adequate patient relief. While the incidence of side effects with nabilone therapy is higher than with active controls, the side effects generally are mild to moderate in intensity, resolve over time, and do not impact patient preference for nabilone over other medications. To minimize the risk for and severity of side effects and improve patient tolerance, it is important to “start low and go slow” in terms of initial dose and dose titration. While studies comparing nabilone to modern antiemetics are anticipated, nabilone is an additional tool in the oncologist’s efforts to control nausea and improve the tolerability of potentially life-saving chemotherapy.

Potential uses of nabilone in cancer patients

A better understanding of the mechanism of action of endocannabinoids has led to investigation of the potential benefit of pharmaceutical cannabinoids for the treatment of other symptoms and side effects of therapy and diseases. Published evidence supports the possible use of nabilone and other cannabinoids in cancer patients to treat radiotherapy-induced nausea, depression and anxiety, sleep disorders, and pain, particularly neuropathic pain (Fabre and McLendon 1981; Priestman et al 1984, 1987; Kalant 2001; Croxford 2003; Ben Amar 2006; Berlach et al 2006; Wissel et al 2006). The efficacy of dronabinol to treat cachexia/wasting in AIDS patients suggested that cannabinoids may be useful for treating this syndrome in cancer patients, although this has not been demonstrated in a recent trial (Strasser et al 2006).

Pain is a common symptom among cancer patients, affecting 18% to 49% at diagnosis and nearly 75% of those patients with advanced disease (Daut and Cleeland 1982; Bonica 1990). Preclinical data support the efficacy of cannabinoids in a broad range of pain models, including neuropathic and chronic pain, for which there is significant evidence (Mack and Joy 2001). Up-regulation of CB1 receptors are key to the analgesic effects of cannabinoids in both chronic and neuropathic pain, and CB2 receptors also appear to play an important role (Croxford 2003).

Data are accumulating for the efficacy of pain management in humans. Notcutt and colleagues reported that cannabinoid therapy reduced either one or both of two primary symptoms by 50% in 34 patients with chronic pain, most of which was neuropathic pain (Notcutt 2004). Although a retrospective chart review was conducted in patients with chronic non-cancer pain, the findings suggest nabilone might be a useful adjunct in the treatment of chronic pain, as well as other symptoms, in a variety of chronic pain patients (Berlach et al 2006). Nearly 1 of every 2 patients experienced pain relief, and complete pain relief was documented in one fourth of the study cohort. Of note, only one patient had tried fewer than 5 different regimens to treat pain prior to receiving nabilone. Additional benefits of nabilone therapy observed in this study included decreased sleep disturbances, reduced severity of nausea and frequency of vomiting, and improved appetite.

Neuropathic pain poses substantial treatment challenges as it is often unresponsive to conventional therapy (Shakespeare et al 2003). Efficacy of cannabinoids in the treatment of non-malignant neuropathic pain might indicate the usefulness of nabilone therapy in cancer patients with neuropathic pain syndromes. Recently, Wissel and associates reported a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in spasticity-associated pain with nabilone therapy when compared with placebo in patients with upper motor neuron syndrome. (Wissel et al 2006). All patients suffered from chronic spasticity-related pain refractory to medications frequently used to treat neuropathic pain. Nabilone was initiated at a dosage of 0.5 mg daily, which was increased to 1 mg per day after 1 week. Patients continued therapy at this dosage for 3 additional weeks. At the end of 4 weeks of nabilone therapy, patients experienced a median decrease of 2 points on the 11-Point-Box-Text. Nabilone was well tolerated, and most side effects were mild in intensity. The investigators point to the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects as a possible explanation for the benefits of nabilone in their study.

Several studies are currently underway, examining the efficacy and safety of nabilone for the treatment of neuropathic pain in various patient populations, as well as its effects on sleep and other symptoms. Results of these studies may further the understanding of nabilone and its role in cancer patients.

Summary

Cannabinoids have been shown to have effects in a variety of clinical syndromes, including CINV. Nabilone, a newly approved synthetic cannabinoid agonist, has a long history of use as an anti-emetic agent has proven to be effective in patients with CINV. Nabilone may have a role in those patients whose nausea and emesis is not adequately controlled by 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and aprepitant. Nabilone may also be considered in patients with anticipatory nausea, as seen in pre-clinical studies. Further study of nabilone as rescue or adjuvant therapy is warranted in these areas. There is also a growing body of literature to suggest additional benefits in cancer patients, including pain control. Continued study of this class of drugs may yield more indications, not only in patients with malignancies, but also in the wider field of non-malignant diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Diann Peterson for her preparation of an early draft of this manuscript.

References

- Aapro M, Molassiotis A, Oliver I. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:117–21. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0745-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahm JL. A physician’s guide to pain and symptom management in cancer patients. 2. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmedzai S, Carlyle DL, Calder IT, et al. Anti-emetic efficacy and toxicity of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in lung cancer chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1983;48:657–63. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1983.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PLR, Naylor RJ, Joss RA. Neuropharmacology of emesis and its relevance to anti-emetic therapy. Consensus and controversies. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:197–203. doi: 10.1007/s005200050154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aprepitant (Emend®). 2005. [package insert]. Merck and Co., Inc

- Ben Amar M. Cannabinoids in medicine: a review of their therapeutic potential. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlach DM, Shir Y, Ware MA. Experience with the synthetic cannabinoid in chronic noncancer pain. Pain Med. 2006;7:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonica JJ. Evolution and current status of pain programs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1990;5:368–74. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(90)90032-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HS, Correia JA, MacLeod SM. Nabilone versus prochlorperazine for control of cancer chemotherapy-induced emesis in children: a double-blind, crossover trial. Pediatrics. 1987;79:946–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford SM, Buckman R. Nabilone and metoclopramide in the treatment of nausea and vomiting due to cisplatinum: a double blind study. Med Oncol Tumor Pharmacother. 1986;3:39–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02934575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxford JL. Therapeutic potential of cannabinoids in CNS disease. CNS Drugs. 2003;17:179–202. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham D, Bradley CJ, Forrest GJ, et al. A randomized trial of oral nabilone and prochlorperazine compared to intravenous metoclopramide and dexamethasone in the treatment of nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy regimens containing cisplatin or cisplatin analogues. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;24:685–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(88)90300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut RL, Cleeland CS. The prevalence and severity of pain in cancer. Cancer. 1982;50:1913–18. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821101)50:9<1913::aid-cncr2820500944>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana MA, Mart A. Endocannabinoid-mediated short-term synaptic plasticity: depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI) and depolarization-induced suppression of excitation (DSE) Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:9–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn LH, Nagy C, Furnas B, Williams SD. Nabilone: An effective antiemetic in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21(suppl):64–69. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre LF, McLendon D. The efficacy and safety of nabilone (a synthetic cannabinoid) in the treatment of anxiety. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:377S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Katona I, Piomelli D. Role of endogenous cannabinoids in synaptic signaling. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1017–66. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E, Bregman T, Kirkham TC. Endocannabinoids and food intake: Newborn suckling and appetite regulation in adulthood. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:225–34. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralla RJ, de Wit R, Herrstedt J, et al. Antiemetic efficacy of the neurokinin-1 antagonist, aprepitant, plus a 5HT3 antagonist and a corticosteroid in patients receiving anthracyclines or cyclophosphamide in addition to high-dose cisplatin: analysis of combined data from two Phase III randomized clinical trials. Cancer. 2005;104:864–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg SM. Advances in the management of nausea and vomiting induced by non-cisplatin containing chemotherapeutic regimens. Blood Rev. 1989;3:216–21. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(89)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman TS, Einhorn LH, Jones SE, et al. Superiority of nabilone over prochlorperazine as an antiemetic in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1295–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906073002302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman TS, Jones SE, Dean J, et al. Nabilone: a potent antiemetic cannabinol with minimal euphoria. Biomedicine. 1977;27:331–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, et al. Nausea and emesis remain significant problems of chemotherapy despite prophylaxis with 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 antiemetics. Cancer. 2003;97:2880–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornby PJ. Central neurocircuitry associated with emesis. Am J Med. 2001;111(suppl 8A):106–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00849-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, et al. International union of pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:161–202. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenns K. Importance of nausea. Cancer Nurs. 1994;17:488–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalant H. Medicinal use of cannabis: history and current status. Pain Res Manage. 2001;6:80–91. doi: 10.1155/2001/469629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kris MG, Hesketh PJ, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline for Antiemetics in Oncology: Update 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2932–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Dibble SL, Pickett M, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting and functional status in women treated for breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28:249–55. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberger L, Rowe H. Clinical pharmacology of nabilone, a cannabinol derivative. Clin Pharm Ther. 1975;18:720–26. doi: 10.1002/cpt1975186720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limebeer CL, Hall G, Parker LA. Exposure to a lithium-paired context elicits gapin in rats: A model of anticipatory nausea. Physiol Behav. 2006;88:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch ME. Preclinical science regarding cannabinoids as analgesics: an overview. Pain Res Manage. 2005;10(suppl A):7A–14A. doi: 10.1155/2005/169093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack A, Joy J. Marijuana as Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Malik IA, Khan WA, Qazilbash M, et al. Clinical efficacy of lorazepam in prophylaxis of anticipatory acute and delayed nausea and vomiting induced by high doses of cisplatin. A prospective randomized trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 1995;18:170–5. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199504000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BR, Wiley JL. Mechanism of action of cannabinoids: how it may lead to treatment of cachexia, emesis, and pain. J Support Oncol. 2004;2:305–14. discussion 314–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiri E, Jhangiani H, Vredenburgh JJ, et al. Efficacy of dronabinol alone and in combination with ondansetron versus ondansetron alone for delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:533–43. doi: 10.1185/030079907x167525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morran C, Smith DC, Anderson DA, et al. Incidence of nausea and vomiting with cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective randomized trial of antiemetics. BMJ. 1979;1:1323–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6174.1323-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, Kirshner JJ, et al. Anticipatory nausea and vomiting in the era of 5-HT3 antiemetics. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:244–7. doi: 10.1007/s005200050161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahas G, Harvey DJ, Sutin K, et al. A molecular basis of the therapeutic and psychoactive properties of cannabis (D9-tetrahydrocannabinol) Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:721–30. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. 2006 [online] Accessed 9 September 2006. URL: http://www.meds.com/pdq/supportive_pro.html.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Antiemesis. v2.2006 [online] 2006 Accessed 9 September 2006. URL: http://www.nccn.org.

- Navari R. Pathogenesis-based treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting – two new agents. J Support Oncol. 2003;1:89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederle N, Schutte J, Schmidt CG. Crossover comparison of the antiemetic efficacy of nabilone and alizapride in patients with nonseminomatous testicular cancer receiving cisplatin therapy. Klin Wochenschr. 1986;64:362–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01728184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiranen A, Mattson K. A cross-over comparison of nabilone and prochlorperazine for emesis induced by cancer chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1985;8:336–40. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198508000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiranen A, Mattson K. Antiemetic efficacy of nabilone and dexamethasone: a randomized study of patients with lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10:325–9. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198708000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notcutt W, Price M, Miller R, et al. Initial experiences with medicinal extracts of cannabis for chronic pain: Results from 34 ’N of 1’ studies. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:440–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, Kemp SW. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) interferes with conditioned retching in Suncus murinus: an animal model of anticipatory nausea and vomiting (ANV) Neuroreport. 2001;12:749–51. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103260-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA, Kwiatkowska M, Mechoulam R. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol, but not ondansetron, interfere with conditioned retching reactions elicited by a lithium-paired context in Suncus murinus: An animal model of anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D. The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signaling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:873–84. doi: 10.1038/nrn1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD, et al. on behalf of the Aprepitant Protocol 054 Study Group. Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer. 2003;97:3090–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy M, Fennelly JJ, Towers M. Prospective randomized double-blind trial of nabilone versus domperidone in the treatment of cytotoxic-induced emesis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1986;17:285–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00256701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestman TJ, Priestman SG. An initial evaluation of nabilone in the control of radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Clin Radiol. 1984;35:265–6. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(84)80088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestman SG, Priestman TJ, Canney PA. A double-blind randomised cross-over comparison of nabilone and metoclopramide in the control of radiation-induced nausea. Clin Radiol. 1987;38:543–4. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(87)80151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi D, Delvaux N, Farvacques C, et al. Prevention of adjustment disorders and anticipatory nausea secondary to adjuvant chemotherapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study assessing the usefulness of alprazolam. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1384–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.7.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Hickok JT, et al. Nausea and vomiting remain a significant clinical problem. J Pain Symptom Mange. 2000;20:113–21. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker E, Kathmann M. Modulation of transmitter release via presynaptic cannabinoid receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:565–72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg L. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: state of the art in 2006. J Support Oncol. 2006;(suppl 1):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare DT, Boggild M, Young C. Anti-spasticity agents for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001332. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhorst U, Klosterhalfen S, Klosterhalfen W, et al. Anticipatory nausea in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: classical conditioning etiology and therapeutical implications. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1993;28:177–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02691224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser F, Luftner D, Possinger K, et al. Comparison of orally administered cannabis extract and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in treating patients with cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome: a multicenter, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial from the Cannabis-In-Cachexia-Study-Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3394–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Weaver CB, et al. Rankings and symptom assessments of side effects from chemotherapy: insights from experienced patients with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2004;13:219–27. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0710-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramér MR, Carroll D, Campbell FA, et al. Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanscoy GJ, Fortner B, Smith R, et al. Preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: the economic implications of choosing antiemetics. Commun Oncol. 2005;2:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra V, Moore T, Brennan E. Inhalation marijuana as an antiemetic for cancer chemotherapy. N Y State J Med. 1988;88:525–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waknine Y. FDA approvals: Lumigan, Cesamet, Omnitrope. Medscape Medical News. 2006 July 14, 2006. Accessed 9 September 2006. URL: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/540937. [Google Scholar]

- Ward A, Holmes B. Nabilone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1985;30:127–44. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198530020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser W, Berger A. Practical management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Oncology. 2005;19:637–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissel J, Haydn, Muller J, et al. Low dose treatment with the synthetic cannabinoid nabilone significantly reduces spasticity-related pain. A double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Neurol. 2006;20:2218–20. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]