Abstract

The Wnt genes encode a highly conserved class of signaling factors required for the development of several types of tissues including musculoskeletal and neural structures. There is increasing evidence that Wnt signaling is critical for bone mass accrual, bone remodeling, and fracture repair. Wnt proteins bind to cell-surface receptors and activate signaling pathways which control nuclear gene expression; this Wnt-regulated gene expression controls cell growth and differentiation. Many of the components of the Wnt pathway have recently been characterized, and specific loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations in this pathway in mice and in humans have resulted in disorders of deficient or excess bone formation, respectively. Pharmacologically targeting components of the Wnt signaling pathway will allow for the manipulation of bone formation and remodeling and will have several orthopedic applications including enhancing bone formation in nonunion and osteoporosis and restricting pathologic bone formation in osteogenic tumors and heterotopic ossification.

The Wnt genes encode a highly conserved class of at least 19 secreted cysteine-rich signaling factors with multiple roles during embryonic development, adult tissue repair, and tumorigenesis [1–3]. They provide a paradigm of the concept that cellular genes which are normally present during embryogenesis and which regulate tissue development are reactivated during tissue repair and can be aberrantly activated in cancers [1, 4]. Wnt genes and their signaling pathway play critical roles in cell fate determination, cell growth, and differentiation of several types of tissues. [2] Recent studies of human orthopedic diseases and specific mouse models suggest a clear role for Wnt signaling in the regulation of bone formation, repair, and remodeling [4–11]. Therefore, either enhancing or suppressing Wnt signaling by manipulating components of the signaling pathway may provide a potent therapeutic approach to treating disorders of excessive or diminished bone formation.

The Wnt signaling pathway

Wnt signaling proceeds through at least two distinct pathways, a traditional or canonical pathway and a non-canonical pathway. The canonical pathway signals through β-catenin, while the non-canonical pathway uses different mediators including G proteins [2, 12]. The vast majority of published studies, including those on the roles of Wnt signaling in osteogenesis, have examined the canonical pathway, and that will be the focus of this review.

The canonical pathway is initiated by Wnt ligands binding to a complex receptor composed of members of the frizzled gene family and low density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins (LRP5 and LRP6; Fig. 1). The binding of Wnt ligands to this receptor complex activates a signaling pathway transduced by the cytoplasmic proteins glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and β-catenin (Fig. 1). In the absence of Wnt signaling, cytoplasmic levels of β-catenin are low because it is phosphorylated by GSK-3. Phosphorylated β-catenin is targeted to a degradation pathway mediated by the APC protein. In the presence of Wnt signaling, GSK-3 is inactivated, thus, preventing phosphorylation of β-catenin. Unphosphorylated β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and enters the nucleus where it associated with the T cell factor (Tcf)/lymphoid enhancing factor (Lef) transcription factors to regulate gene expression (Fig. 1) [1, 2, 4, 5].

Fig. 1.

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Wnt proteins bind to a receptor complex composed of members of the frizzled gene family (Fzd) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related proteins (LRP). Receptor binding inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3). In the absence of Wnt signaling, GSK-3 phosphorylates β-catenin and targets it to a degradation pathway mediated by the APC protein (APC). In the presence of Wnt signaling, β-catenin escapes phosphorylation and degradation and accumulates in the cytoplasm. Excess β-catenin enters the nucleus where it associates with the lymphoid enhancing factor (Lef)/T cell factor (Tcf) transcription factors to regulate gene expression. Secreted frizzled-related proteins (Sfrps) contain the ligand binding domain of frizzled but lack the transmembrane region; they can bind the Wnt ligands but cannot transduce the Wnt signal, and thus, effectively block Wnt signaling. Dickkopf (DKK) proteins are secreted factors which also block Wnt signaling by binding to the LRP receptors

There are several antagonists to the Wnt signaling pathway (Fig. 1). Intracellular antagonists include GSK-3 and APC-3. Extracellular antagonists include secreted frizzled-related proteins (Sfrps) which contain the ligand binding domain of frizzled but lack the transmembrane region [13, 14]. These proteins can bind the Wnt ligands but cannot transduce the Wnt signal, and thus, effectively block Wnt signaling. Dickkopf (DKK) proteins are secreted factors which interfere with Wnt signaling by binding to the LRP-5 and LRP-6 receptors [13, 15]. The latter two antagonists, Sfrps and DKK, are specific antagonists of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway and are proteins which may be commercially produced and used to block Wnt signaling. GSK-3 and APC, in contrast, have more global roles in cellular function and are thus less likely to be targeted for specific blockage of Wnt signaling.

Wnt signaling in development and disease

Wnt genes were initially identified as genes potentially responsible for mouse mammary tumor virus-induced carcinogenesis in mice [3]. They were subsequently noted to be present in several different species and important for the development of several different types of tissues including limbs and midbrain [1, 2]. Accumulating evidence suggests that Wnt signaling is highly regulated spatially and temporally. Specific Wnt genes are expressed at very precise times and locations; aberrant expression of Wnt signaling in the wrong tissue or at the wrong time in development can result in cancers [16].

Several human diseases have been linked to abnormal Wnt signaling. Mutations in APC, which impair its ability to degrade β-catenin, or mutations in β-catenin itself which stabilize β-catenin, both result in constitutively active Wnt signaling and have been linked to familial adenomatous polyposis and colon cancer [16, 17]. Increased Wnt signaling has been observed in several other cancers including osteosarcomas and Ewing’s sarcoma [18, 19]. Mutations which impair Wnt signaling have been linked to the rare human disorder tetra-amelia marked by the absence of all four limbs and craniofacial abnormalities [20].

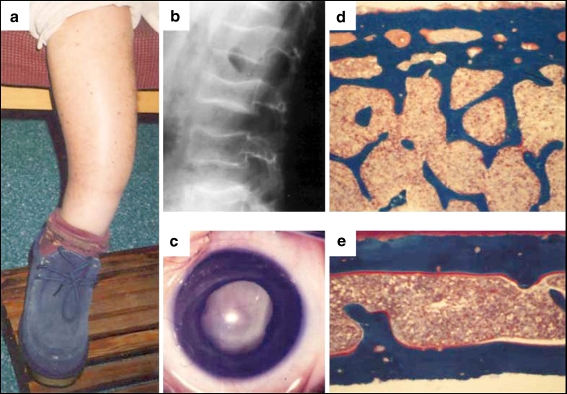

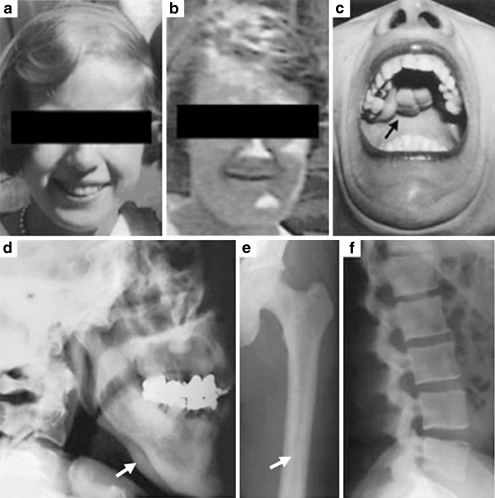

A specific role for Wnt signaling in bone formation was revealed by naturally occurring human mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway. Loss-of-function mutations in the Wnt co-receptor LRP5, which essentially blocks the canonical pathway, results in osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome [21] characterized by a low bone mass, an increased incidence of fragility fractures, and visual defects (Fig. 2a–e). In contrast, gain-of-function mutations in LRP5, which prevent inhibition of LRP5 by the inhibitor DKK, effectively increase Wnt signaling and are associated with a high bone mass phenotype characterized by increased bone mineral density, thickened femoral cortices, and increased vertebral body density (Fig. 3a–f) [22, 23]. The alternate phenotypes in these two disorders suggest that Wnt signaling increases bone formation and/or density, and understanding the mechanism by which this occurs may allow us to treat disorders of bone insufficiency and excess.

Fig. 2.

Clinical characteristics of osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome (OPPG). a Photograph of the lower extremity of a 40-year-old woman with OPPG demonstrating angular deformity secondary to multiple childhood fragility fractures. b Lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine in a 10-year-old child with OPPG demonstrating abnormal vertebral body flattening and concavity. c Photograph of the right eye of a 3-month-old child with OPPG demonstrating leukocoria (a retrolental membrane). d, e Iliac crest bone biopsies (both at 40× magnification) from an unaffected 2.5-year-old child (control) (d) and from a 2.5-year-old child with OPPG (e). The control biopsy is substantially thicker than the OPPG biopsy. (Reproduced with permission from Elsevier [21]

Fig. 3.

Clinical characteristics of high bone density syndrome due to a mutation in LRP5. a, b Photographs of an affected patient at age 12 (a) and 45 years (b) show the development of a wide, deep mandible. c A large, lobulated torus palatinus in an affected member. d–f Characteristic radiographic findings including an abnormally thick mandibular ramus (d), a thickened femoral cortex with narrowed medullary cavity (arrow; e), and dense vertebrae (f). Reproduced with permission from [22]

Roles in bone remodeling

The association of LRP5 mutations to bone mass disorders in humans led to several molecular studies to (1) confirm the role of Wnt signaling in bone regulation and (2) identify the mechanism by which Wnt regulates bone remodeling. Transgenic studies in which the LRP5 gene was disrupted in mice resulted in a phenotype identical to osteoporosis pseudoglioma syndrome in humans; mice demonstrated diminished bone formation and osteopaenia [24]. Mice engineered to express LRP mutations which are associated with high bone mass phenotypes in humans resulted in a similar phenotype with increases in both total and trabecular bone mineral density. A marked increase in vertebral compressive strength and femoral bending strength were observed in these LRP5 mutants [25]. These findings suggest that Wnt signaling via LRP5 regulates bone accrual.

The above studies suggest that increased Wnt signaling results in increased bone formation, whereas diminished Wnt signaling results in decreased bone formation. Thus, manipulating the balance of Wnt agonists such as β-catenin or Wnt antagonists such as DKK and Sfrps to either increase or decrease Wnt signaling may effectively regulate the rate of bone formation [6–9, 26–29]. For example, stabilization of β-catenin in transgenic mice results in an osteopetrotic phenotype with increased bone mass and rib osteomata [7, 9]. In contrast, disrupting β-catenin expression in transgenic mice results in osteopaenia [6, 7, 9, 27]. Deletion of sFRP-1 in transgenic mice increases trabecular bone mineral density and volume with increased osteoblast proliferation and differentiation [26], whereas introducing sFRP-1 into osteoblasts blocks Wnt signaling and accelerates osteoblast cell death [26]. DKK overexpression in transgenic mice results in severe osteopenia with a 49% reduction in the number of osteoblasts [28]; in contrast, mice engineered to lack DKK demonstrate significant increases in bone mass, bone formation, and osteoblast numbers. [29]

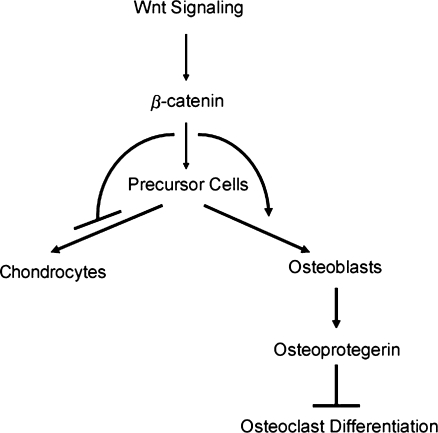

Several basic science studies have suggested that Wnt signaling enhances bone formation by regulating osteoblast and osteoclast proliferation and differentiation (Fig. 4). Removing β-catenin from osteoblast progenitor cells prevent them from differentiating into mature osteocalcin-expressing osteoblasts [10, 11]. Interestingly, these progenitor cells differentiate into chondrocytes. This indicates that Wnt signaling acts as a master musculoskeletal switch preventing progenitor cells from differentiating down the chondrocyte lineage and targeting them instead to the osteoblast lineage [6, 9]. Furthermore, there is recent evidence that Wnt signaling, via β-catenin, can upregulate the expression of osteoprotegerin in osteoblasts [7, 27]. Because osteoprotegerin inhibits the differentiation of osteoclasts [30], Wnt signaling may increase bone mass partly by blocking osteoclast-mediated bone resorption (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effects of Wnt signaling on osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation. Wnt-regulated bone formation and remodeling result from an enhancement of mesenchymal precursor cell differentiation into osteoblasts. Wnt signaling blocks the alternative chondrocyte differentiation pathway. Differentiating osteoblasts synthesize and secrete osteoprotegerin in response to Wnt signaling; osteoprotegerin blocks osteoclast differentiation. Thus, Wnt signals increase bone formation by enhancing osteoblast-mediated bone formation and inhibiting osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and chondrocyte differentiation

Conclusions

Studies on human bone mass disorders and genetic manipulation in transgenic mice have provided compelling evidence for a role for Wnt signaling in regulating bone mass, bone density, and remodeling. The increased understanding of the Wnt signaling pathway has identified specific regulators, such as DKK and Sfrps, which may be manipulated to either enhance or repress Wnt signaling. The established role of the Wnt pathway in osteoporosis, high bone mass disorders, and certain osteogenic tumors suggest that pharmacologic manipulation of this pathway with, for example, commercially produced sFRPs or DKK, may provide a powerful method to specifically intervene in the abnormal signaling in these diseases [5]. The orthopedic applications of such pharmacologic agents will likely be expanded to several other conditions of bone deficiency such as nonunion, or bone excess, such as heterotopic ossification.

References

- 1.Logan CY, Nusse R (2004) The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20:781–810 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Nusse R (2005) Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res 15:28–32 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Nusse R, Varmus HE (1992) Wnt genes. Cell 69:1073–1087 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Westendorf JJ, Kahler RA, Schroeder TM (2004) Wnt signaling in osteoblasts and bone diseases. Gene 341:19–39 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Baron R, Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S (2006) Wnt signaling: a key regulator of bone mass. Curr Top Dev Biol 76:103–127 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, et al. (2005) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell 8:739–750 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Glass DA, 2nd, Bialek P, Ahn JD, et al. (2005) Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev Cell 8:751–764 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gregory CA, Gunn WG, Reyes E, et al. (2005) How Wnt signaling affects bone repair by mesenchymal stem cells from the bone marrow. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1049:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hill TP, Spater D, Taketo MM, et al. (2005) Canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Dev Cell 8:727–738 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hu H, Hilton MJ, Tu X, et al. (2005) Sequential roles of Hedgehog and Wnt signaling in osteoblast development. Development 132:49–60 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Rodda SJ, McMahon AP (2006) Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development 133:3231–3244 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Montcouquiol M, Crenshaw EB, 3rd, Kelley MW (2006) Noncanonical Wnt signaling and neural polarity. Annu Rev Neurosci 29:363–386 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kawano Y, Kypta R (2003) Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. J Cell Sci 116:2627–2634 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ladher RK, Church VL, Allen S, et al. (2000) Cloning and expression of the Wnt antagonists Sfrp-2 and Frzb during chick development. Dev Biol 218:183–198 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Glinka A, Wu W, Delius H, et al. (1998) Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature 391:357–362 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Behrens J, Lustig B (2004) The Wnt connection to tumorigenesis. Int J Dev Biol 48:477–487 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Nathke IS (2004) The adenomatous polyposis coli protein: the Achilles heel of the gut epithelium. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20:337–366 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Hoang BH, Kubo T, Healey JH, et al. (2004) Expression of LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) as a novel marker for disease progression in high-grade osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer 109:106–111 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Uren A, Wolf V, Sun YF, et al. (2004) Wnt/Frizzled signaling in Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 43:243–249 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Niemann S, Zhao C, Pascu F, et al. (2004) Homozygous WNT3 mutation causes tetra-amelia in a large consanguineous family. Am J Hum Genet 74:558–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Gong Y, Slee RB, Fukai N, et al. (2001) LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell 107:513–523 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Boyden LM, Mao J, Belsky J, et al. (2002) High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor-related protein 5. N Engl J Med 346:1513–1521 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Little RD, Carulli JP, Del Mastro RG, et al. (2002) A mutation in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 gene results in the autosomal dominant high-bone-mass trait. Am J Hum Genet 70:11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kato M, Patel MS, Levasseur R, et al. (2002) Cbfa1-independent decrease in osteoblast proliferation, osteopenia, and persistent embryonic eye vascularization in mice deficient in Lrp5, a Wnt coreceptor. J Cell Biol 157:303–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Babij P, Zhao W, Small C, et al. (2003) High bone mass in mice expressing a mutant LRP5 gene. J Bone Miner Res 18:960–974 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Bodine PV, Zhao W, Kharode YP, et al. (2004) The Wnt antagonist secreted frizzled-related protein-1 is a negative regulator of trabecular bone formation in adult mice. Mol Endocrinol 18:1222–1237 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Holmen SL, Zylstra CR, Mukherjee A, et al. (2005) Essential role of beta-catenin in postnatal bone acquisition. J Biol Chem 280:21162–21168 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Li J, Sarosi I, Cattley RC, et al. (2006) Dkk1-mediated inhibition of Wnt signaling in bone results in osteopenia. Bone 39:754–766 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Morvan F, Boulukos K, Clement-Lacroix P, et al. (2006) Deletion of a single allele of the Dkk1 gene leads to an increase in bone formation and bone mass. J Bone Miner Res 21:934–945 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Roodman GD (2006) Regulation of osteoclast differentiation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1068:100–109 [DOI] [PubMed]