Abstract

Linker histone H1 plays an important role in chromatin folding. Phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinases is the main post-translational modification of histone H1. We studied the effects of phosphorylation on the secondary structure of the DNA-bound H1 carboxy-terminal domain (CTD), which contains most of the phosphorylation sites of the molecule. The effects of phosphorylation on the secondary structure of the DNA-bound CTD were site-specific and depended on the number of phosphate groups. Full phosphorylation significantly increased the proportion of β-structure and decreased that of α-helix. Partial phosphorylation increased the amount of undefined structure and decreased that of α-helix without a significant increase in β-structure. Phosphorylation had a moderate effect on the affinity of the CTD for the DNA, which was proportional to the number of phosphate groups. Partial phosphorylation drastically reduced the aggregation of DNA fragments by the CTD, but full phosphorylation restored to a large extent the aggregation capacity of the unphosphorylated domain. These results support the involvement of H1 hyperphosphorylation in metaphase chromatin condensation and of H1 partial phosphorylation in interphase chromatin relaxation. More generally, our results suggest that the effects of phosphorylation are mediated by specific structural changes and are not simply a consequence of the net charge.

INTRODUCTION

H1 linker histones are involved in chromatin structure and gene regulation (1). Histone H1 contains three distinct domains: a short amino-terminal domain (20−35 amino acids), a central globular domain (∼70 amino acids) and a long carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) (∼100 amino acids) (2). Several studies indicate that the ability of linker histones to stabilize chromatin folding resides in the CTD of the molecule (3). The CTD displays a high degree of conformational flexibility. In aqueous solution, the CTD is dominated by the random coil and turn-like conformations in rapid equilibrium with the unfolded state, but when it interacts with DNA it folds cooperatively. The DNA-bound structure is extremely stable and includes α-helix, β-sheet, turns and open loops (flexible regions) (4). The H1 CTD thus appears to belong to the so-called intrinsically disordered proteins undergoing coupled binding and folding (5–7). In addition, in the presence of macromolecular crowding agents the unbound CTD acquires the properties of a molten globule with native-like secondary structure and compaction (8).

The phenotypic roles of histone H1 may be determined by complementary and overlapping effects of stoichiometry, subtype composition and post-translational modifications. Phosphorylation of the consensus sequences of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), (S/T)-P-X-(K/R), is the main post-translational modification affecting histone H1 (9). In mammalian subtypes these sequences are localized mostly in the CTD. The maximum number of phosphate groups often corresponds to the number of CDK sites in the molecule. Histone H1 is phosphorylated in a cell cycle-dependent manner. The levels of phosphorylation are lowest in G1 and rise during S and G2 (10,11). During interphase, H1 subtypes are present as a mixture of unphosphorylated and low-phosphorylated species with a proportion of 35–75% of unphosphorylated forms, according to the particular subtype and cell line and the moment of the cell cycle. The highest number of phosphorylated sites is found in mitosis, when chromatin is maximally condensed. Phosphorylation of H1 variants may occur site-specifically during the phases of the cell cycle (12).

It is not clear how H1 phosphorylation affects chromatin condensation during interphase and mitosis. A number of studies indicate that interphase phosphorylation is involved in chromatin relaxation (13–15); however, in metaphase chromosomes, H1 is hyperphosphorylated, and it has been shown that H1 hyperphosphorylation is required to maintain metaphase chromosomes in their condensed state (16).

Here we report the effects of partial and full phosphorylation on the secondary structure of the CTD of histone H1 using IR spectroscopy. We have also estimated the relative affinities for the DNA and the DNA condensing capacity of the different phosphorylated species of the CTD. The results, showing site-specific effects depending on the number and position of phosphate groups may contribute to reconcile the roles of H1 phosphorylation in interphase and mitosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression and purification of the CTD

The CTD of histones H1° and H1e were obtained from recombinant Escherichia coli (M15) as described previously (4). The sequence encoding the CTD of histone H1e was amplified from mouse genomic DNA by PCR. The primers used for the amplification reaction were 5′AAACTCCATATGAAGGCGGCTTCCGGTGAG3′ and 5′GAACTCGAGCTTTTTCTTGGCTGCTTT3′. The amplification products were cloned in the pET21 vector (Novagen; Darmstadt, Germany) using the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites to yield the expression vector pCTH1e. The recombinant protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified as described for the CTD of histone H1° (CH1°).

Construction of mutants of the CDK2 sites

The mutant clones for the CDK2 phosphorylation sites of the CH1° were obtained by PCR using the QuickChange Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Strategene; Amsterdam, Netherlands) following the manufacturer's instructions. The primers used for each phosphorylation site were mutated so that the threonine residue was changed to alanine. For threonine at position 118 the primers were 5′TCAAGAAAGTGGCAGCTCCAAAGAAGGCA3′ and 5′TGCCTTCTTTGGAGCTGCCACTTTCTTGA3′. For position T140 the primers were 5′AGAAACCCAAAGCCGCCCCTGTCAAGAAG3′ and 5′CTTCTTGACAGGGGCGGCTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTCT3′. For position T152 the primers were 5′GCTGCCGCGCCCAAGAAAGCAAAAAGCC3′ and 5′GGCTTTTTGGCTTTCTTGGGCGCGGCAGC3′. Double and triple mutants were obtained in successive rounds of PCR. The introduction of the correct mutation was evaluated by DNA sequencing of the recombinant clones. The recombinant plasmids were named according to the position mutated in each case. Clones were expressed and purified as described for the wild-type CTD.

In vitro phosphorylation assay

The CTD of histone H1 subtypes were phosphorylated in vitro with CDK2-cyclin A kinase (New England Biolabs; Ipswich, MA, USA). Phosphorylation reactions were carried out in 50 mM Tris.HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 20mM dithiotreitol, pH 7.5, plus 200 µM ATP and 1 U of CDK2-cyclin A per 5 µg of CTD. The mixture was incubated at 30°C for 1 h and the reaction buffer was eliminated by gel filtration on a HiTrap desalting column (GE Healthcare; München, Germany). The extent of phosphorylation was evaluated by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

IR spectroscopy

The CTD of histone H1 were measured at 50mg/ml in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0 plus 140 mM NaCl. DNA–protein complexes contained the appropriate amount of DNA for each protein/DNA ratio (w/w): Measurements were performed on a Nicolet Magna II 5770 spectrometer equipped with a MCT detector, using a demountable liquid cell with calcium fluorine windows and 50 μm spacers for D2O medium and 6 μm spacers for H2O medium measurements. Typically, 1000 scans for each background and sample were collected and the spectra were obtained with a nominal resolution of 2 cm−1, at 22°C. The protein concentration for the D2O measurements was 5 mg/ml, while for the H2O measurements it was 20 mg/ml. The spectra of the complexes were recorded both in H2O and D2O to facilitate the assignment of the amide I components (4). Data treatment and band decomposition were as previously described (17). The DNA contribution to the spectra of the complexes with the C-terminus was subtracted using a DNA sample of the same concentration; the DNA spectrum was weighted so as to cancel the symmetric component of the phosphate vibration at 1087 cm−1 in the difference spectra as described in (18).

Affinity measurements

The apparent relative affinities of the unphosphorylated and the different phosphorylated species of CH1° were estimated in competition experiments as previously described (19). The different forms of CH1° were made to compete with an approximately equal amount of the CTD of histone H1t (CH1t). A total of 3.0 μg of CTD was mixed with 0.5 μg of DNA in a final volume of 25 μl in 0.14 M NaCl, 0.01 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 5% glycerol. The complexes were recovered by centrifugation at 14 000 g for 10 min. The protein composition of the complexes and of the free protein left in the supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by staining with Amido Black. The relative affinities were obtained with the expression:

where the concentration of complexes, [iDNA] and [jDNA], was obtained from the band intensities in the pellets and the concentration of free protein, [i]free and [j]free, from the band intensities of the supernatants.

Band shift gel electrophoresis

Complexes were formed in 0.14 M NaCl, 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 and incubated at room temperature for 30 min before separation on 1% agarose gels. The electrophoresis buffer was 36 mM Tris, 30 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.7 (20). Gels were stained with ethidium bromide. The dsDNA fragment of 50 bp used in complex formation was obtained by annealing the oligonucleotide 5′CTATGATATATAGATAGTTAATGTAATATGATATAGATATAGGGATCC3′ with its complementary sequence. The dsDNA fragment of 108 bp was obtained from pUC19 by PCR using the primers 5′GCGGTTAGCTCCTTCGGTCCTC3′ and 5′GGATGGCATGACAGTAAGAGAA3′.

RESULTS

Conformational changes associated to full phosphorylation of the DNA-bound CTD of histone H1

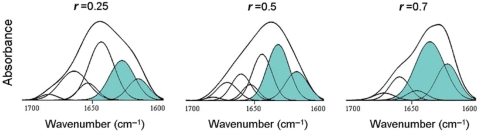

The apparently conflicting roles of H1 phosphorylation suggest the existence of specific effects that depend on the number and position of phosphate groups. This led us to examine the secondary structure of the different phosphorylated forms of the DNA-bound CTD using IR spectroscopy. The CH1° contains three CDK sites. Phosphorylation of CH1° at all three sites brought about a large structural rearrangement characterized by a decrease in the proportion of α-helix and an increase in that of β-sheet (Figure 1; Table 1). The extent of the structural change appeared to be dependent on the protein to DNA ratio (r, w/w). At r = 0.25 or lower the α-helix decreased from 24% in the unphosphorylated CTD to 8% and the β-sheet increased from ∼24% to ∼36%. At r = 0.5 the α-helix further decreased down to 6% and the β-sheet increased up to ∼46%. At r = 0.7, which was approximately the saturation ratio, the CTD eventually became an all β protein, with no α-helix, ∼16% flexible regions, ∼20% turns and ∼74% β-sheet.

Figure 1.

Amide I decomposition of DNA-bound triphosphorylated CH1° at different protein/DNA ratio (r) (w/w). The spectra were measured in D2O. The buffer was 10 mM HEPES plus 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, at 20°C. The protein concentration was 5 mg/ml. The β-structure components are highlighted in blue.

Table 1.

Percentages of secondary structure of the DNA-bound triphosphorylated (3p) CH1°

| Assignment | 3p |

0p |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

r = 0.25 |

r = 0.5 |

r = 0.7 |

r = 0.7 |

|||||||||||||

| D2O |

H2O |

D2O |

H2O |

D2O |

H2O |

D2O |

H2O |

|||||||||

| Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | |

| Turns | 1681 | 1 | 1677 | 6 | 1682 | 8 | ||||||||||

| Turns | 1681 | 2 | 1679 | 6 | 1670 | 10 | 1680 | 8 | 1671 | 4 | 1671 | 9 | 1668 | 13 | 1673 | 9 |

| Turns | 1663 | 20 | 1661 | 14 | 1660 | 13 | 1663 | 19 | 1659 | 14 | 1661 | 13 | 1659 | 15 | 1663 | 16 |

| α-helix | 1654 | 8 | 1653 | 6 | 1650 | 24 | ||||||||||

| α-helix/random coil | 1655 | 21 | 1654 | 7 | 1652 | 24 | ||||||||||

| Flexible regions | 1641 | 22 | 1646 | 21 | 1646 | 6 | 1640 | 18 | ||||||||

| Random coil/flexible regions | 1644 | 35 | 1645 | 23 | 1646 | 6 | 1639 | 18 | ||||||||

| Random coila | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Random coilb | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| β-sheet | 1630 | 24 | 1632 | 28 | 1633 | 31 | 1633 | 26 | 1636 | 52 | 1637 | 45 | 1630 | 16 | 1630 | 16 |

| Low frequency β-sheet | 1618 | 11 | 1616 | 9 | 1620 | 16 | 1619 | 19 | 1623 | 24 | 1624 | 27 | 1617 | 8 | 1618 | 9 |

The values corresponding to the unphosphorylated (0p) domain are included for comparison and were taken from Roque et al. (3). Band position (cm−1) and percentage area (%) and assignment of the components were obtained after curve fitting of the amide I band in D2O and H2O and in 140 mM NaCl. The values were rounded off to the nearest integer.

aThe value corresponds to the difference between the components at 1641–46 cm−1in D2O and H2O.

bThe value corresponds to the difference between the components at 1650–55 cm−1 in H2O and D2O.

We also examined the secondary structure of the CTD of mouse H1e (CH1e), which shares only a 44% of sequence identity with CH1°. Like CH1°, it has three CDK sites. The unphosphorylated CH1e had a significantly higher starting proportion of α-helix (34%) and less β-structure (18%) than CH1° (Supplementary Figure 1, Table 1). Upon full phosphorylation, the amount of α-helix decreased and that of β-structure increased in function of r, as in CH1°, but in contrast to the latter, the fully phosphorylated CH1e conserved a significant proportion of α-helix (17%) and the increase in β-structure was less pronounced (55%).

Phosphorylation did not affect the overall conformation of the CTD free in solution. In physiological salt the conformation of both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated CTD was dominated by the random coil and turn conformations (Supplementary Table 2). Phosphorylation did not alter the proportions of secondary structure motifs in crowded conditions either (Supplementary Table 2). The specific structural changes promoted by phosphorylation appeared thus to be dependent on DNA interaction.

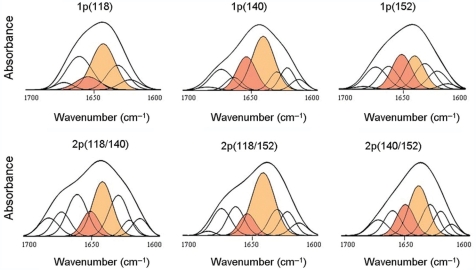

Site-specific effects of partial phosphorylation on the secondary structure of the DNA-bound CTD

In order to examine the effects of phosphorylation of one or two of the three TPXK sites present in CH1°, we prepared a series of single and double T→A mutants of the TPXK sites; so that, three monophosphorylated species, CH1°(p118), CH1°(p140) and CH1°(p152), and three diphosphorylated species, CH1°(p118p140), CH1°(p118p152) and CH1°(p140p152), were obtained. None of these T/A substitutions significantly altered the structure of the DNA-bound domains, as judged by the similarity of their spectra to that of the wild-type domain (Supplementary Table 3).

Of the three CDK sites, phosphorylation of T118 affected the structure the most, leading to a decrease in the α-helix content from 24% to 10% and to the appearance of 18−20% of random coil, which was absent in the unphosphorylated domain (Figure 2, Table 2). This amount of random coil together with a ∼17% of flexible regions gave a significant 35% of undefined structure. The region upstream to the first phosphorylation site is known to be in a helical conformation in the unphosphorylated domain and is thus a clear candidate for destabilization by phosphorylation at this site (21). The amount of undefined structure in CH1°(p140) was also very high (36%), but in this case the flexible regions (27%) predominated over the random coil (9%) and the α-helix decreased only slightly (down to 19%). The structure of CH1°(p152) was the closest to that of the unphosporylated domain as the changes in the proportions of secondary structure motifs did not exceed 6%. Doubly phosphorylated domains had increased amounts of random coil/flexible regions (Figure 2, Table 3). Those containing pT118, i.e. CH1°(p118p140) and CH1°(p118p152), had a low proportion of α-helix (9−10%), while in CH1°(p140p152) it decreased only slightly (17%), which also suggests that pT118 has a central role in α-helix destabilization. All mono- and diphosphorylated species had similar amounts of β-structure (∼27%), which were only slightly higher than those of the unphosphorylated domain (∼24%). The secondary structure of the mono- and diphosphorylated species was not dependent on the protein to DNA ratio (Supplementary Table 4). The dependence of the conformation on r thus appears as a specific property of the hyperphosphorylated species.

Figure 2.

Amide I decomposition of the DNA-bound CH1° phosphorylated at one or two positions. The numbers in parenthesis indicate the phosphorylated position. The spectra were measured in D2O. The buffer was 10 mM HEPES plus 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.0 at 20°C. The protein concentration was 5 mg/ml. The protein/DNA ratio (w/w) was 0.5. The α-helix component is highlighted in red and the random coil/flexible regions component is highlighted in orange.

Table 2.

Percentages of secondary structure of the DNA-bound monophosphorylated species (1p) of the CH1° at r = 0.5

| Assignment | 1p(118) |

1p(140) |

1p(152) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2O |

H2O |

D2O |

H2O |

D2O |

H2O |

|||||||

| Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | |

| Turns | 1682 | 2 | 1683 | 2 | 1680 | 1 | 1681 | 4 | ||||

| Turns | 1672 | 4 | 1675 | 16 | 1672 | 14 | 1674 | 7 | 1671 | 15 | 1672 | 7 |

| Turns | 1661 | 27 | 1665 | 13 | 1662 | 6 | 1661 | 11 | 1661 | 13 | 1660 | 14 |

| α-helix | 1654 | 10 | 1653 | 19 | 1650 | 21 | ||||||

| α-helix/random coil | 1656 | 30 | 1655 | 29 | 1656 | 22 | ||||||

| Flexible regions | 1643 | 17 | 1641 | 27 | 1644 | 22 | ||||||

| Random coil/flexible regions | 1643 | 35 | 1640 | 36 | 1640 | 20 | ||||||

| Random coila | 18 | 9 | 2 | |||||||||

| Random coilb | 20 | 10 | 1 | |||||||||

| β-sheet | 1632 | 17 | 1635 | 18 | 1630 | 8 | 1629 | 15 | 1632 | 16 | 1634 | 17 |

| Low frequency β-sheet | 1624 | 7 | 1622 | 10 | 1622 | 3 | 1622 | 11 | 1622 | 12 | ||

| Low frequency β-sheet | 1623 | 7 | 1614 | 5 | 1614 | 5 | 1614 | 3 | 1614 | 2 | ||

Band position (cm−1) and percentage area (%) and assignment of the components were obtained after curve fitting of the amide I band in D2O and H2O and in 140 mM NaCl. The values were rounded off to the nearest integer.

The numbers in parenthesis indicate the phosphorylated positions.

aThe value corresponds to the difference between the components at 1640–44 cm−1 in D2O and H2O.

bThe value corresponds to the difference between the components at 1650–56 cm−1 in H2O and D2O.

Table 3.

Percentages of secondary structure of the DNA-bound diphosphorylated species (2p) of the CH1° at r = 0.5

| Assignment | 2p(118/140) |

2p(118/152) |

2p(140/152) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2O |

H2O |

D2O |

H2O |

D2O |

H2O |

|||||||

| Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | Band (cm−1) | % | |

| Turns | 1682 | 8 | 1681 | 3 | 1682 | 2 | ||||||

| Turns | 1672 | 10 | 1672 | 6 | 1672 | 13 | 1680 | 5 | 1671 | 9 | 1680 | 8 |

| Turns | 1661 | 19 | 1660 | 25 | 1661 | 13 | 1667 | 18 | 1660 | 13 | 1668 | 8 |

| α-helix | 1650 | 10 | 1653 | 9 | 1650 | 17 | ||||||

| α-helix/random coil | 1656 | 11 | 1656 | 17 | 1657 | 20 | ||||||

| Flexible regions | 1644 | 26 | 1643 | 31 | 1644 | 27 | ||||||

| Random coil/flexible regions | 1642 | 24 | 1641 | 37 | 1640 | 29 | ||||||

| Random coila | 2 | 6 | 2 | |||||||||

| Random coilb | 1 | 8 | 3 | |||||||||

| β-sheet | 1630 | 18 | 1633 | 17 | 1630 | 11 | 1633 | 12 | 1631 | 16 | 1632 | 19 |

| Low frequency β-sheet | 1622 | 5 | 1621 | 11 | 1623 | 10 | 1624 | 10 | 1622 | 11 | 1622 | 13 |

| Low frequency β-sheet | 1615 | 6 | 1616 | 1 | 1614 | 5 | 1616 | 7 | 1615 | 5 | 1615 | 5 |

Band position (cm−1) and percentage area (%) and assignment of the components were obtained after curve fitting of the amide I band in D2O and H2O and in 140 mM NaCl. The values were rounded off to the nearest integer. The numbers in parenthesis indicate the phosphorylated positions.

aThe value corresponds to the difference between the components at 1640–44 cm−1 in D2O and H2O.

bThe value corresponds to the difference between the components at 1650–57 cm−1 in H2O and D2O.

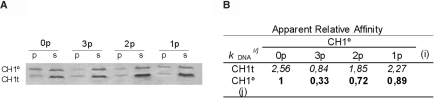

Phosphorylation had a small effect on the affinity of the CTD for the DNA

We examined the relative affinities of unphosphorylated CTD (0p), one monophosphorylated species (1p), CH1°(p118), one diphosphorylated species (2p), CH1°(p118p140) and the triphosphorylated species (3p). Relative affinities were estimated by competition of the different phosphorylated species of CH1° with an equivalent amount of the CH1t for a limited amount of DNA as previously described (Figure 3) (19). Phosphorylation caused a small decrease of the affinity of the CTD for the DNA, which was proportional to the number of phosphate groups. The apparent relative affinities were 1 (0p): 0.9 (1p): 0.7 (2p): 0.3 (3p). A higher effect was not expected on a purely electrostatic basis given the small proportion of the CH1° positive charge (40 lysine residues) represented by the incorporated phosphate groups (a maximum of three). In contrast, sea-urchin testis-specific H1 and H2B have most basic amino acids residues in their N-terminal regions in multiple SPKK sites; in this case, general Ser phosphorylation could effectively abolish the net charge of the entire N-terminal region and thus greatly weaken its interaction with DNA (22).

Figure 3.

Effect of phosphorylation of CH1° on relative affinity. Competitions of pairs of CTDs for a limited amount of DNA. (A) The unphosphorylated CH1° (0p), the fully phosphorylated species (3p), a diphosphorylated species, CH1°/p118p144 (2p) and a monophosphorylated species, CH1°/p118 (1p), were made to compete with the unphosphorylated CH1t. p, pellet; s, supernatant. (B) The relative affinities of CH1° species (in bold numbers) were obtained from their relative affinities for CH1t (in italics). The values are the average of three independent determinations.

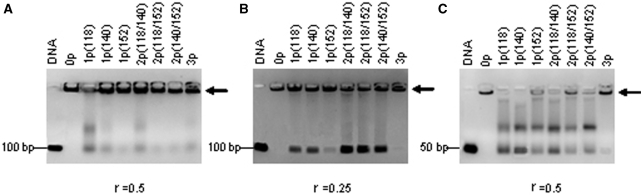

Differential aggregation of DNA fragments by fully and partially phosphorylated CTD

The capacity of unphosphorylated CTD and its different phosphorylated species to aggregate DNA fragments was investigated by band-shift-gel-electrophoresis. With DNA fragments of 100 bp and r = 0.5, the unphosphorylated CTD and all phosphorylated species formed large complexes that could not enter the gel (Figure 4A). Decreasing either the size of the DNA or the r value revealed different aggregation capacities for the different CTD forms. Figure 4B and C shows bandshift assays with DNA fragments of 100 bp at r = 0.25 and with DNA fragments of 50 bp at r = 0.5. In both conditions, the unphosphorylated C-terminus aggregated the totality of the DNA fragments. Phosphorylation of either one or two sites decreased the aggregation capacity of the C-terminus significantly. Surprisingly, the hyperphosphorylated C-terminus regained to a large extent the aggregation capacity of the unphosphorylated C-terminus, displaying a strong aggregation band and little free DNA.

Figure 4.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of DNA fragments with CH1° and its phosphorylated species. Binding was carried out in physiological salt (0.14 M NaCl). (A) DNA of 100 bp and r = 0.5; (B) DNA of 100 bp and r = 0.25; (C) DNA of 50 bp and r = 0.5. The arrow indicates the aggregates that do not enter the gel.

Electron microscopy of the DNA complexes confirmed the bandshift results. The complexes had varied morphologies, but the aggregates formed with either unphosphorylated or fully phosphorylated CTD were consistently larger and denser than those with partially phosphorylated species (Supplementary Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

We have shown that full phosphorylation of the DNA-bound CTD brings about a large structural change consisting in a significant increase in β-structure accompanied by a decrease in α-helix. The effect is apparent at the lowest r values (r = 0.15), but is favored by the saturation of the DNA lattice, suggesting that protein-protein interactions contribute to the conformational transition. Partial phosphorylation induces in general a large proportion of undefined structure (random coil and flexible regions), but, in contrast to full phosphorylation, it does not lead to a significant increase in β-structure.

The increase of β-sheet content and the loss of α-helical structure in the H1 CTD following full phosphorylation is a kind of structural conversion similar to that observed in amyloidogenic proteins during fibril formation (23). In prion encephalopaties, the analogy can be pushed further as it has been shown that interaction with DNA converts the α-helical cellular isoform into a β-isoform similar to that found in the fibrilar state (24). Furthermore, H1 has been found associated to amyloid-like fibrils (25).

The effects of phosphorylation on the affinity of the CTD for the DNA were moderate: a three-fold decrease for the fully phosphorylated domain and smaller effects for the mono- and diphosphorylated species. It is interesting to note that in spite of its lower affinity for DNA, the fully phosphorylated domain showed a higher aggregation capacity of DNA fragments than the partially phosphorylated species. The aggregation capacity of the fully phosphorylated species was indeed nearly as high as that of the unphosphorylated domain. The high condensing capacity of the fully phosphorylated species might have a structural basis. A general feature of the sequences of the CTD of H1 histones is the large proportion of basic residues present as doublets: about 75% in mammalian somatic subtypes. In β-sheets, consecutive side chains project alternatively above and below the sheet-like structure. It is likely that the abundance of Lys doublets together with the β-sheet structure generates a binding motif with two cationic surfaces, particularly in the hyperphosphorylated CTD. Such a structure seems well suited to the electrostatic crosslinking of two segments of DNA.

The site-specificity of the effects of phosphorylation on the secondary structure and DNA condensing capacity of the CTD, together with the moderate effect of phosphorylation on the affinity for the DNA, suggest that the effects of phosphorylation are mediated by specific structural changes and are not a simple effect of the net charge. According to this, the properties of hyperphosphorylated H1 would not represent the extreme of a continuous variation in molecular properties depending on the number of phosphates, but would be determined by the specific structures associated with full phosphorylation.

The reasons for general H1 hyperphosphorylation in metaphase chromosomes remain unclear. However, the specific structural features, in particular the high β-sheet content and the higher aggregation capacity of the fully phosphorylated domain suggest that hyperphosphorylation may play a role, together with other condensing factors, in metaphase chromatin condensation. Conversely, the loss of defined structure and the lower condensing capacity of some mono- and diphosphorylated species could explain the relaxing effect of partially phosphorylated H1 on chromatin structure during interphase, particularly in S phase.

Some reports support the occurrence of opposite effects of moderate as opposed to full phosphorylation. SV40 minichromosomes reconstituted with either unphosphorylated or hyperphosphorylated H1 were more compact and less efficient as substrate in in vitro replication compared with minichromosomes reconstituted with moderately phosphorylated H1 (26). It has been suggested that hyperphosphorylation of histone H1 and H3 leads to inhibition of glucocorticoid receptor-mediated chromatin remodeling and inactivation of the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter by preventing the association of transcription factors with the promoter in vivo. In contrast, a moderate amount of H1 phosphorylation contributes significantly to the induction of transcription from the MMTV promoter (27). It has also been shown that phosphorylation of only one site within the CTD of H1b severely disrupts the interaction between H1b and the heterochromatin protein 1α (HP1α), a key component of mammalian heterochromatin (28).

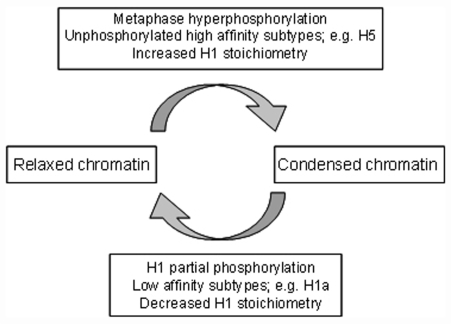

Chromatin condensation associated with hyperphosphorylation in metaphase chromosomes may be structurally and mechanistically distinct from other condensed chromatin states associated with unphosphorylated H1, such as those of chicken erythrocyte nuclei (29), sea urchin sperm (30), Tetrahymena macronuclei or interphase heterochromatin (31). Figure 5 shows a schematic representation of some H1 related factors that may be involved in the transition between relaxed and condensed chromatin in different systems.

Figure 5.

H1 related factors involved in the transition between relaxed and condensed chromatin.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank O. Castell for his help with the electron microscopy experiments. Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (Spain), Grant BFU2005-02143. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for the article was provided by Grant BFU2005-02143.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zlatanova J, Caiafa P, van Holde K. Linker histone binding and displacement: versatile mechanism for transcripcional regulation. FASEB J. 2000;14:1697–1704. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0869rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman PG, Chapman GE, Moss T, Bradbury EM. Studies on the role and mode of operation of the very-lysine-rich histone H1 in eukaryote chromatin. The three structural regions of the histone H1 molecule. Eur. J. Biochem. 1977;77:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu X, Hansen JC. Revisiting the structure and functions of the linker histone C-terminal tail domain. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2003;81:173–176. doi: 10.1139/o03-041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roque A, Iloro I, Ponte I, Arrondo JL, Suau P. DNA-induced secondary structure of the carboxyl-terminal domain of histone H1. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32141–32147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunasekaran K, Tsai CJ, Kumar S, Zanuy D, Nussinov R. Extended disordered proteins: targeting function with less scaffold. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:81–85. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracken C, Iakoucheva LM, Romero PR, Dunker AK. Combining prediction, computation and experiment for the characterization of protein disorder. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructered proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roque A, Ponte I, Suau P. Macromolecular crowding induces a molten globule state in the C-terminal domain of histone H1. Biophys. J. 2007;93:2170–2177. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.104513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swank RA, Th'ng JP, Guo XW, Valdez J, Bradbury EM, Gurley LR. Four distinct cyclin-dependent kinases phosphorylate histone H1 at all of its growth-related phosphorylation sites. Biochemistry. 1997;36:13761–13768. doi: 10.1021/bi9714363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talasz H, Helliger W, Puschendorf B, Lindner H. In vivo phosphorylation of histone H1 variants during the cell cycle. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1761–1767. doi: 10.1021/bi951914e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradbury EM, Inglis RJ, Matthews HR, Sarner N. Phosphorylation of very-lysine-rich histone in Physarum polycephalum. Correlation with chromosome condensation. Eur. J. Biochem. 1973;33:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarg B, Helliger W, Talasz H, Förg B, Lindner HH. Histone H1 phosphorylation occurs site-specifically during interphase and mitosis: identification of a novel phosphorylation site on histone H1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6573–6580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth SY, Allis CD. Chromatin condensation: does histone H1 dephosphorylation play a role? Trends Biochem. Sci. 1992;17:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contreras A, Hale TK, Stenoien DL, Rosen JM, Mancini MA, Herrera RE. The dynamic mobility of histone H1 is regulated by cyclin/CDK phosphorylation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:8626–8636. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8626-8636.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lever MA, Th’ng JPH, Sun X, Hendzel M. Rapid Exchange of histone H1.1 on chromatin in living cells. Nature. 2000;408:873–876. doi: 10.1038/35048603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Th'ng JP, Guo XW, Swank RA, Crissman HA, Bradbury EM. Inhibition of histone phosphorylation by staurosporine leads to chromosome decondensation. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9568–9573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arrondo JL, Goñi FM. Structure and dynamics of membrane proteins as studied by infrared spectroscopy. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1999;72:367–405. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(99)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vila R, Ponte I, Collado M, Arrondo JL, Suau P. Induction of secondary structure in a COOH-terminal peptide of histone H1 by interaction with the DNA: an infrared spectroscopy study. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:30898–30903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orrego M, Ponte I, Roque A, Buschati N, Mora X, Suau P. Differential affinity of mammalian histone H1 somatic subtypes for DNA and chromatin. BMC Biol. 2007;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rickwood D, Hames BD. Oxford: IRL Press; 1990. Gel electrophoresis of Nucleic Acids a Practical Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vila R, Ponte I, Jiménez MA, Rico M, Suau P. A helix-turn motif in the C-terminal domain of histone H1. Protein Sci. 2000;9:627–636. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.4.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green GR, Lee HJ, Poccia DL. Phosphorylation weakens DNA binding by peptides containing multiple “SPKK” sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:11247–11255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aguzzi A, Polymenidou M. Mammalian prion biology: one century of evolving concepts. Cell. 2004;116:313–327. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordeiro Y, Machado F, Juliano L, Juliano MA, Brentani RR, Foguel D, Silva JL. DNA converts cellular prion protein into the β-sheet conformation and inhibits prion peptide aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:49400–49409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duce JA, Smith DP, Blake RE, Crouch PJ, Li QX, Masters CL, Trounce IA. Linker histone H1 binds to disease associated amyloid-like fibrils. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;361:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halmer L, Gruss C. Effects of cell cycle dependent histone H1 phosphorylation on chromatin structure and chromatin replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1420–1427. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.8.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhattacharjee RN, Archer TK. Transcriptional silencing of the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter through chromatin remodelling is concomitant with histone H1 phosphorylation and histone H3 hyperphosphorylation at M phase. Virology. 2006;346:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hale TK, Contreras A, Morrison AJ, Herrera RE. Phosphorylation of the linker histone H1 by CDK regulates its binding to HP1alpha. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner TE, Hartford JB, Serra M, Vandegrift V, Sung MT. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of histone V (H5): controlled condensation of avian erythrocyte chromatin. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of histone H5. II. Circular dichroic studies. Biochemistry. 1977;16:286–290. doi: 10.1021/bi00621a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poccia D. In: The molecular biology of fertilization. Schatten H, Schatten G, editors. New York: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roth SY, Schulman IG, Richman R, Cook RG, Allis CD. Characterization of phosphorylation sites in histone H1 in the amitotic macronucleus of Tetrahymena during different physiological states. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:2473–2482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.