Abstract

This paper describes a two-step procedure for generating cubic nanocages and nanoframes. In the first step, Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes were synthesized through the galvanic replacement reaction between Ag nanocubes and an aqueous HAuCl4 solution. The second step involved the selective removal (or dealloying) of Ag from the alloy nanoboxes with an aqueous etchant based on Fe(NO3)3 or NH4OH. The use of a wet etchant other than HAuCl4 for the dealloying process allows one to better control the wall thickness and porosity of resultant nanocages because there is no concurrent deposition of Au. By increasing the amount of Fe(NO3)3 or NH4OH added to the dealloying process, nanoboxes derived from 50-nm Ag nanocubes could be converted into nanocages and then cubic nanoframes with surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peaks continuously shifted from the visible region to 1200 nm. It is also possible to obtain nanocages with relatively narrow SPR peaks (with an FWHM as small as 180 nm) by controlling the amount of HAuCl4 used for the galvanic replacement reaction and thus optimization of the percentage of Au in the alloy nanoboxes.

Hollow nanoparticles of noble metals have unique physical and chemical characteristics that differentiate them from many other types of nanostructured materials.1 They have also been recognized for a range of applications, including catalysis,2 optical sensing,3 drug delivery,4 biomedical imaging,5 as well as photothermal cancer treatment.6 Among various synthetic routes, the one based on galvanic replacement reaction has proven to be the most effective in generating hollow nanostructures from a number of noble metals.1,7 It has been demonstrated that bimetallic alloy hollow nanostructures composed of Ag and Au, Pd, or Pt could be conveniently prepared by reacting Ag nanostructures with a compound containing a less reactive noble metal such as Au, Pd, or Pt. In particular, Au/Ag nanoboxes (nanostructures with hollow interiors) and nanocages (nanostructures with hollow interiors and porous walls) with tunable surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peaks can be routinely synthesized by reacting Ag nanocubes with HAuCl4 in an aqueous solution. By increasing the amount of HAuCl4 added to a suspension of Ag nanocubes, the nanocubes can be controlled to evolve from solid objects into cubic nanoboxes and then nanocages. As a well-established example, the SPR peaks of gold hollow nanoboxes and nanocages can be readily tuned from the visible to the near-infrared (NIR) region by varying the wall thickness relative to the overall dimension.8

Although the protocol based on the galvanic replacement reaction with HAuCl4 works well for Ag nanostructures of a variety of shapes, it has a drawback that limits our ability to achieve a tight control over the wall thickness and porosity for the resultant nanocages. In the early stage of the reaction (or when a relatively small amount of HAuCl4 is added), Ag atoms are dissolved from the nanocube, which also serves as a template for the deposition of Au atoms produced via the replacement reaction:

| (1) |

Some of the Ag atoms can also diffuse into the lattice of deposited Au to form an alloy shell. As a result, the intermediate products of this synthesis are nanoboxes with their walls consisting of Au/Ag alloys. In the late stage of the reaction (or when a large amount of HAuCl4 is added), the Ag atoms in the alloy walls are selectively extracted through a dealloying process to generate nanocages with compositions approaching pure gold.8 In this dealloying process, Au atoms are concurrently produced and deposited onto the walls, causing additional changes to both the wall thickness and porosity. Such an unwanted coupling between Ag dealloying and Au deposition makes it difficult to fine tune or precisely control the wall thickness, porosity, and thus optical property of the resultant nanocage. Since deposition of Au is unavoidable whenever HAuCl4 is added, it has also been very difficult to produce nanocages with ultrathin walls by relying on the previously demonstrated protocols. Here we demonstrate that all these technical problems will vanish when dealloying of Ag and deposition of Au are separated from each other.

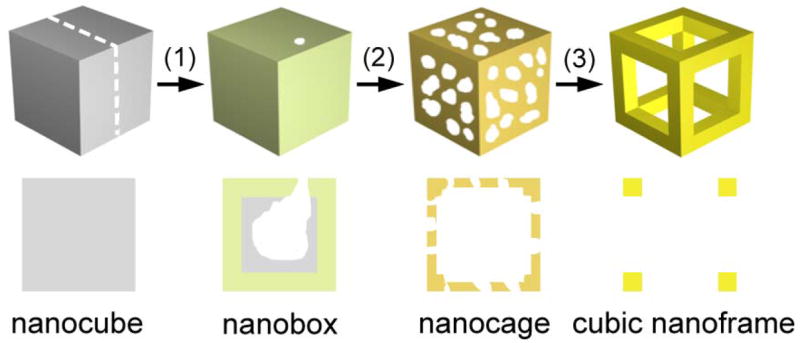

The dealloying or selective dissolution of Ag from Au/Ag alloys has been investigated for decades.9 It has been shown that porous structures can be formed by treating a Au/Ag alloy with an oxidative etchant such as nitric acid or perchloric acid.10 In the present work, we demonstrate that the Ag contained in the walls of Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes can be selectively removed using anaqueous solution containing Fe(NO3)3 or NH4OH, two commonly used wet enchants for pure silver.11 Figure 1 shows a schematic detailing all major steps involved in the new protocol, by which Au/Ag nanoboxes, Au/Ag nanocages, and finally Au cubic nanoframes are obtained. In the first step, the galvanic replacement reaction was performed by reacting Ag nanocubes with a specific amount of aqueous HAuCl4 solution to form nanoboxes composed of a Au/Ag alloy shell and some un-reacted Ag metal inside the shell. After the galvanic replacement reaction, Fe(NO3)3 solution instead of more HAuCl4 is introduced into the suspension of Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes and the remaining Ag in the nanoboxes is dissolved according to the following chemical reaction:11a

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating the formation of nanocage made of a Au/Ag alloy and then cubic nanoframe of pure Au by selectively removing the Ag atoms from a Au/Ag alloy nanobox with an aqueous etchant based on Fe(NO3)3 or NH4OH. The nanobox is, in turn, prepared using the galvanic replacement reaction between the Ag nanocube and an aqueous solution of HAuCl4 (step 1). When silver is dealloyed using Fe(NO3)3 or NH4OH, the nanobox first evolves into a porous nanocage (step 2). As more etchant is added, the silver can be completely removed to generate a cubic nanoframe (step 3). The drawing in the lower panel corresponds to the cross-section indicated in the upper panel for the nanocube.

| (2) |

The Au component, however, will remain in the nanoboxes. Unlike the previously demonstrated dealloying process based on HAuCl4 that also involves Au deposition, the reaction between the Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes and Fe(NO3)3 is simply a dealloying process. With the progress of the reaction (step 2 in Figure 1), the nanobox develops into nanocages with increasing porosity as more Ag is removed from the alloy wall. Since the reaction between Ag and Fe(NO3)3 only produces water soluble species, the porosity of the nanocage will be determined by the amount of Fe(NO3)3 added to the reaction solution. In the last step, when the Ag is close to complete removal, the central portion of each side wall of the nanocage will disappear and the final product takes the form of a cubic nanoframe.

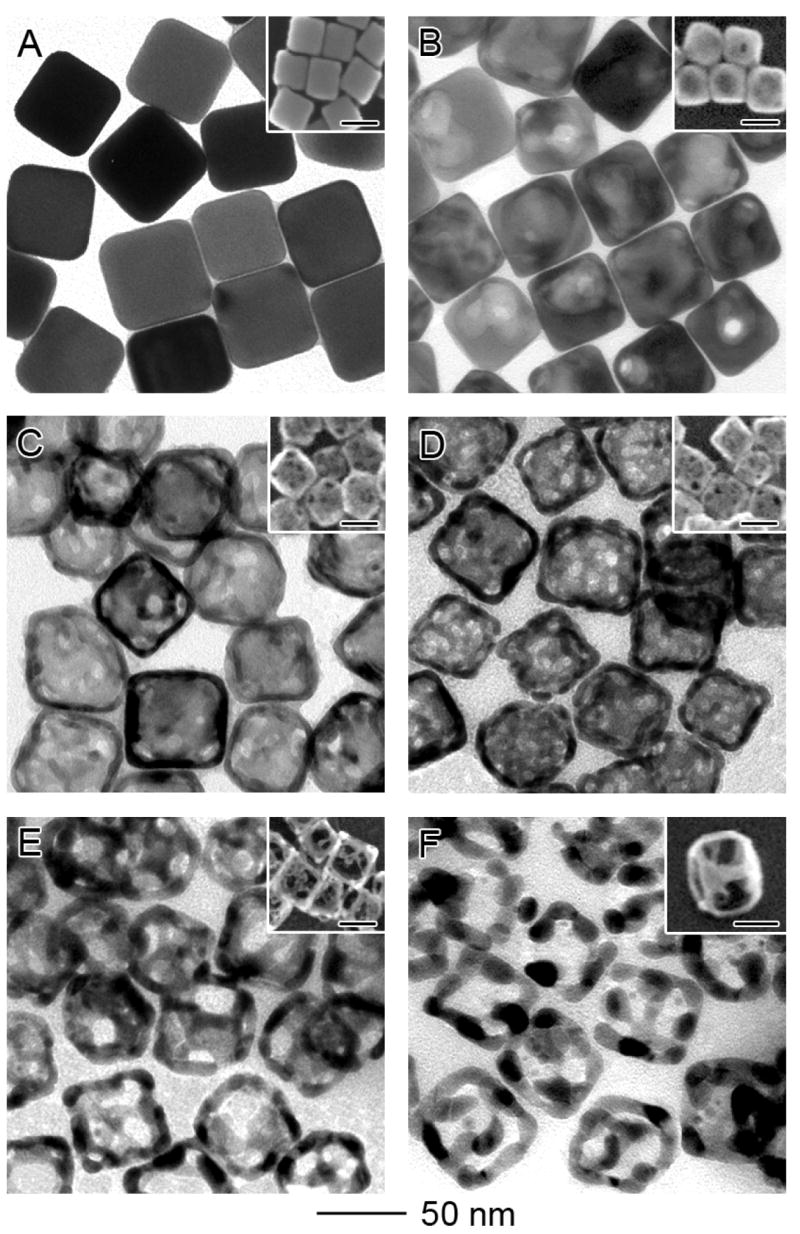

Figure 2 shows transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of nanostructures that were obtained by reacting 50-nm Ag nanocubes with HAuCl4 solution, followed by selective removal of the remaining Ag with an etchant based on Fe(NO3)3. Silver nanocubes with fairly sharp corners (Figure 2A) were, in turn, synthesized using a polyol process12 and then used as sacrificial templates to generate Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes through the galvanic replacement reaction. With the addition of 4 mL HAuCl4 aqueous solution (0.2 mM), the Ag nanocubes were partially dissolved to form nanoboxes with relatively thick walls (Figure 2B). The reaction followed the same mechanism described in a previous publication.8 Different from our previous work, the replacement reaction between Ag nanocubes and HAuCl4 was stopped at an early stage when only a small void was formed inside each nanobox. There was also a small opening on the surface of the nanobox, and the remaining Ag was enclosed by a shell made of a Au/Ag alloy. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis of the nanobox sample indicates that the atomic percentage of Au was only 15%.

Figure 2.

TEM and SEM (inset) images of (A) 50-nm Ag nanocubes; (B) Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes obtained by reacting the nanocubes with 4.0 mL of 0.2 mM HAuCl4 aqueous solution; and (C-F) nanocages and nanoframes obtained by etching the nanoboxes with 5, 10, 15, 20 μL of 50 mM aqueous Fe(NO3)3 solution. The inset in (F) was obtained at a tilting angle of 45 degrees, clearly showing the 3-D structure of a nanoframe. The scale bars in all insets are 50 nm. EDX analysis indicates the atomic ratio of Au:Ag was 15:85, 30:70, 45:55, 60:40 and 100:0 for samples in (B), (C), (D), (E), and (F), respectively.

After 5 μL of 50 mM aqueous Fe(NO3)3 solution had been introduced, the Au/Ag nanoboxes evolved into nanocages with porous walls (Figure 2C). The percentage of Au in these nanocages was increased to 30%. The pores on the surface of a typical nanocage had an average diameter of 4 nm. As the total volume of Fe(NO3)3 solution was increased to 10 μL, the pore size was enlarged to 6 nm and the number of pores on each nanocage also increased substantially (Figure 2D). After adding a total 15 μL of Fe(NO3)3 solution, the pores merged to form openings as big as ~15 nm in diameter (Figure 2E) and the nanocage turned into a skeleton-like structure. The atomic percentage of Au was further increased to 60%. By the point when a total of 20 μL of Fe(NO3)3 solution was added, essentially all the Ag atoms had been selectively removed and the nanocage became a cubic nanoframe consisting of pure Au (Figure 2F). We also monitored the morphological change involved in each step by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, see the insets). The SEM image captured at a tilting angle of 45 degrees (the inset of Figure 2F) clearly shows the 3D profile of a cubic nanoframe resulting from complete removal of Ag atoms from a Au/Ag nanobox. The increase of porosity with the addition of Fe(NO3)3 was caused by the removal of Ag atoms and the clustering of Au atoms via diffusion, and this scheme is consistent with previously reported theoretical simulations13 and experimental results10a for the dealloying of Ag from Au/Ag bimetallic alloys.

When measured using TEM, the wall thickness of the nanocage appeared to increase slightly with the continuous removal of Ag atoms. When 10, 15, and 20 μL of Fe(NO3)3 solution was added, the average wall thickness was roughly 5, 8 and 10 nm, respectively. However, it should be pointed out these values measured by TEM only reflect the thickness at the edges of each nanocage, rather than the central portion of a side face. In fact, the side face was continuously thinned as more Fe(NO3)3 was added. An explanation for this can be attributed to the fact that the {100} planes are more vulnerable to the etchant, and the Ag atoms in the side faces of a nanobox will be dissolved ahead of those at the edges. With the continuous removal of Ag atoms, the Au atoms left behind on the side faces will diffuse toward the edges of each nanocage, causing the central portion of each face to diminish. As a result, the wall thickness measured by TEM appeared to increase as more Fe(NO3)3 solution was added. It is worth noting that the nanocages and nanoframes are fairly stable structures; their cubic shape was well preserved in the process of SEM/TEM sample preparation. Only a few of them exhibited deformation due to the strong capillary force involved in solvent evaporation.

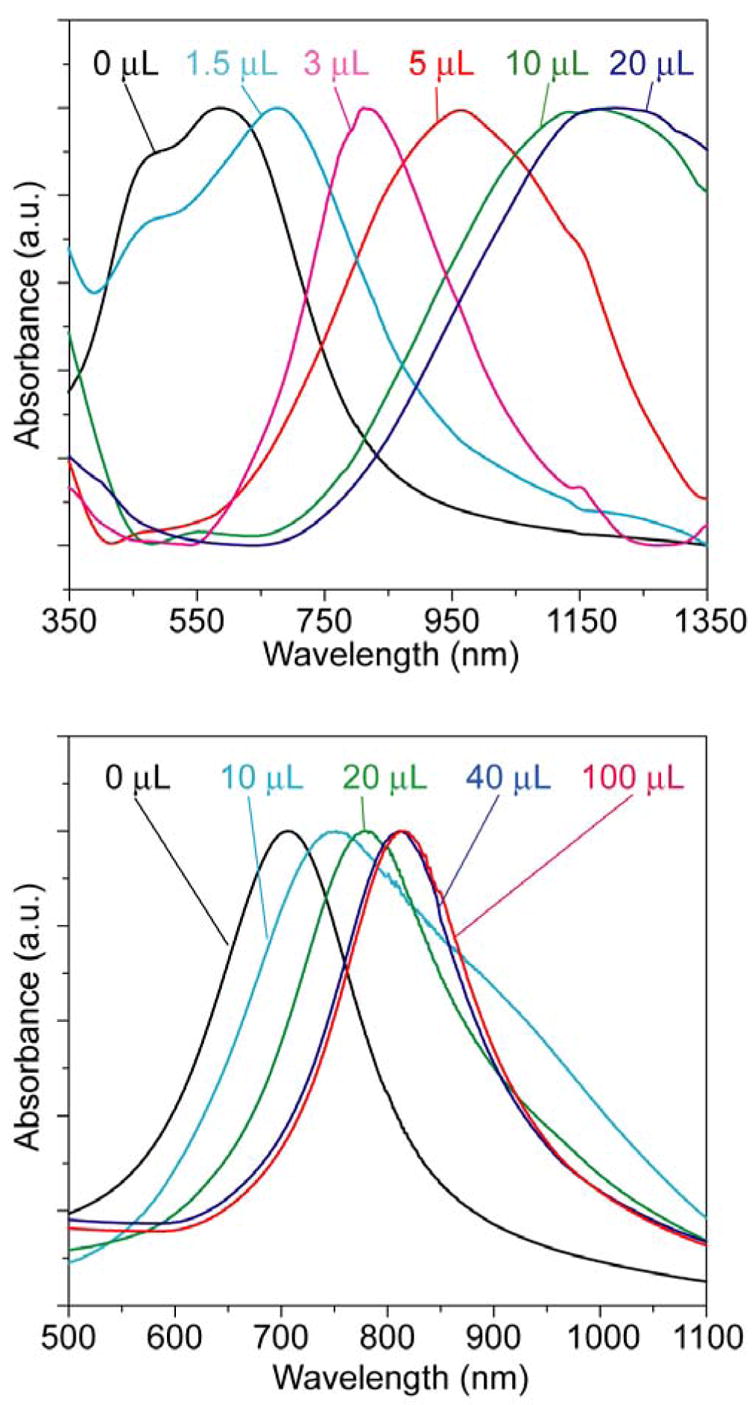

Similar to the synthesis that is solely based on HAuCl4, the spectral changes involved in the dealloying process could also be closely monitored as more Fe(NO3)3 solution was added to the reaction solution. Figure 3A shows the absorbance spectra of nanoboxes, nanocages, and cubic nanoframes as 50-nm Ag nanocubes were titrated with HAuCl4 and then Fe(NO3)3. As expected, the SPR peak was continuously red-shifted from the visible to the NIR region as a result of the galvanic replacement reaction and then dealloying process. As expected, the SPR peak position could be easily tuned to >1000 nm by simply controlling the amount of Fe(NO3)3 solution added into the suspension of Au/Ag nanoboxes. When 1.5, 3, 5, 10 μL of 50 mM aqueous Fe(NO3)3 solution was introduced, the SPR peak was shifted from 540 to 590, 780, 950, and 1150 nm, respectively. The position of the SPR peak of a nanocage is mainly determined by its wall thickness. As the wall thickness decreases, the SPR peak continuously moves toward longer wavelengths. Although the wall thickness of Au nanocages appeared to increase with dealloying when viewed under TEM, the red-shift of SPR peaks indicates that the thickness of wall in the center portion of each side face was actually reduced. After 20 μL of 50 mM Fe(NO3)3 solution had been introduced, the side faces of a nanocage nearly disappeared and the resultant cubic nanoframe displayed a SPR peak around 1210 nm. To verify this result, we have also employed the discrete dipole approximation (DDA) method to calculate the extinction spectrum for a cubic nanoframe of gold with an edge-to-edge length of 50 nm and a wall thickness of 10 nm at the edges. The calculated spectrum (Figure S1) shows a major extinction peak at ~1100 nm, which agrees reasonably well with the spectrum experimentally recorded from the ensemble of a large number of cubic nanoframes.

Figure 3.

Absorbance spectra of 50-nm Au/Ag nanoboxes after etching with different volumes of 50 mM Fe(NO3)3 aqueous solution. (A) The nanocubes were reacted with 4.0 mL of 0.2 mM HAuCl4 solution, followed by etching with 0 to 20 μL of Fe(NO3)3 solution. The SPR peak was red-shifted from 590 (nanoboxes) to 1210 nm (cubic nanoframes). (B) If the nanocubes were reacted with 10.0 mL of 0.2 mM HAuCl4 solution before etching, the SPR peak was shifted from 720 nm to 830 nm when reacted with 0 to 100 μL Fe(NO3)3 solution. Note that the peaks are much narrower than those for the sample in (A). See Figure 4 for TEM images.

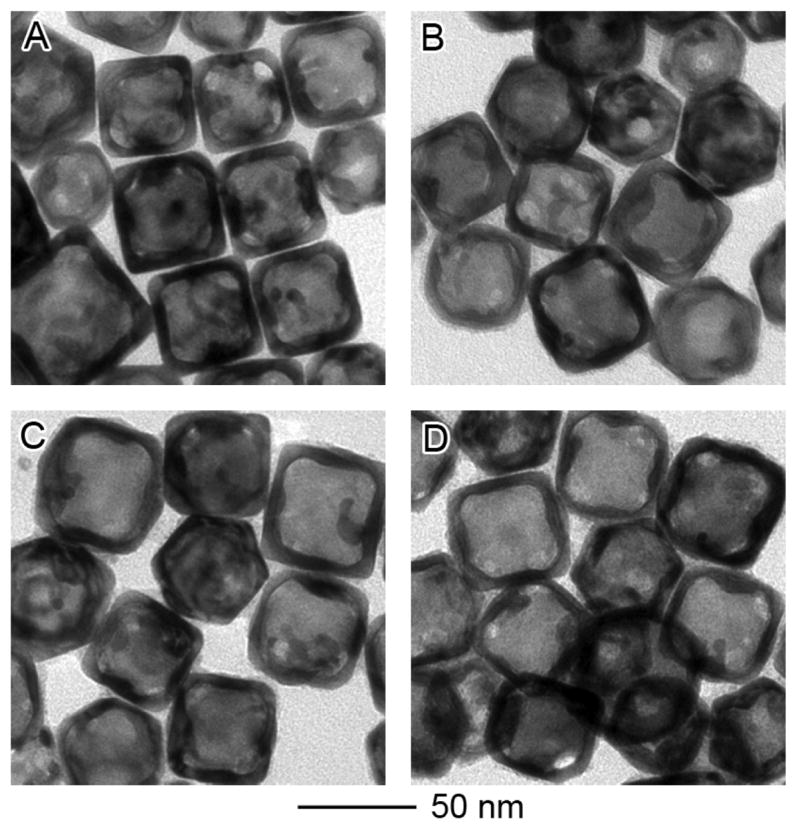

The evolution of SPR spectra for the nanocages and nanoframes is also dependent on the composition of the starting nanoboxes. For nanoboxes prepared by adding 10 mL of 0.2 mM HAuCl4 solution to the 50-nm Ag nanocubes, they had a molar percentage of 30% for Au and an SPR peak at 720 nm. When these nanoboxes were etched with different volumes of aqueous Fe(NO3)3, we also observed a red-shift for the SPR peak (Figure 3B), but the shift was far less significant as compared to the nanoboxes prepared with a Au molar percentage of 15% (Figure 3A). For the nanoboxes containing 30% of Au, the SPR peak was shifted from 720 to 770, 820, 850, and 850 nm, respectively, after 10, 20, 40 and 100 μL of 50 mM Fe(NO3)3 solution had been added. Interestingly, the nanocages prepared using this route showed much narrower SPR peaks as compared to the samples described in Figure 3A: 180 nm versus 350 nm for the FWHM. This observation means that the galvanic replacement reaction between Ag nanocubes and HAuCl4 could be stopped at a stage where a relatively uniform Au/Ag alloy wall was formed and no pure Ag remained inside the shell. Etching of these nanocages with Fe(NO3)3 barely changed the wall thickness (Figure 4) or the FWHM of the absorbance spectra, indicating that the Ag atoms in the Au/Ag alloy walls could not be completely extracted via dealloying. This incompleteness of Ag extraction from Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes containing 30% of Au was also confirmed by EDX, which gave a Au to Ag atomic ratio of 43:57 after 100 μL of 50 mM Fe(NO3)3 solution had been added. Although the exact explanation remains elusive, this observation is similar to the partial dissolution of Ag from a Au/Ag alloy with nitric acid reported by Espiell and coworkers.10a These authors found that Ag could be completely dissolved with 6.56 M HNO3 from Au/Ag alloys whose molar percentages of Au were lower than 54%. However, they did not observe any substantial lose of Ag when Au/Ag alloys with Au percentage above 54% were subjected to the same etchant.

Figure 4.

(A) TEM image of nanoboxes obtained by galvanic replacement reaction between 50-nm Ag nanocubes and 10 mL of 0.2 mM HAuCl4 solution. After etching with (B) 10, (C) 20, and (D) 100 μL of 50 mM aqueous Fe(NO3)3 solution, no significant morphological change was observed. EDX analysis shows that the atomic ratios of Au to Ag are 30:70, 36:64, 40:60, and 43:57 for (A), (B), (C), and (D), respectively.

By etching Au/Ag alloy nanocages with Fe(NO3)3, the shape of the nanocages can be well maintained during the dissolution of Ag. Previously, we have found that the galvanic replacement reaction between HAuCl4 and Ag nanocubes with truncated corners could lead to the formation of Au/Ag nanocages with controllable pores at all corners,1e a new type of nanostructures promising for controlled drug delivery. However, further addition of HAuCl4 to dealloy Ag would change the shape of the nanocages, mainly because the removal of Ag takes place at the corners with {111} facets and the deposition of Au occurs at {100} side faces. Using Fe(NO3)3 instead of HAuCl4 to dealloy Ag would preserve the shape while maximizing the empty space inside each nanocage. Figure 5A shows the TEM image of nanocages obtained by the reacting 0.8 mL of 0.2 mM HAuCl4 solution and 80-nm Ag nanocubes with truncated corners. After replacement reaction, the nanocages showed pinholes at each corner but no opening on the side faces. Those nanocages were then etched with 5 μL of 50 mM Fe(NO3)3 solution (Figure 5B). Although SEM images (Figure 5, insets) of the nanocages before and after etching with Fe(NO3)3 showed essentially no morphological changes for the nanocages, TEM studies indicate dramatic reduction in wall thickness after etching (Figure 5). The reduction in wall thickness can also be inferred from the change in absorbance spectrum – the peak was red-shifted from 550 nm to 1020 nm after etching with Fe(NO3)3 (Figure S2).

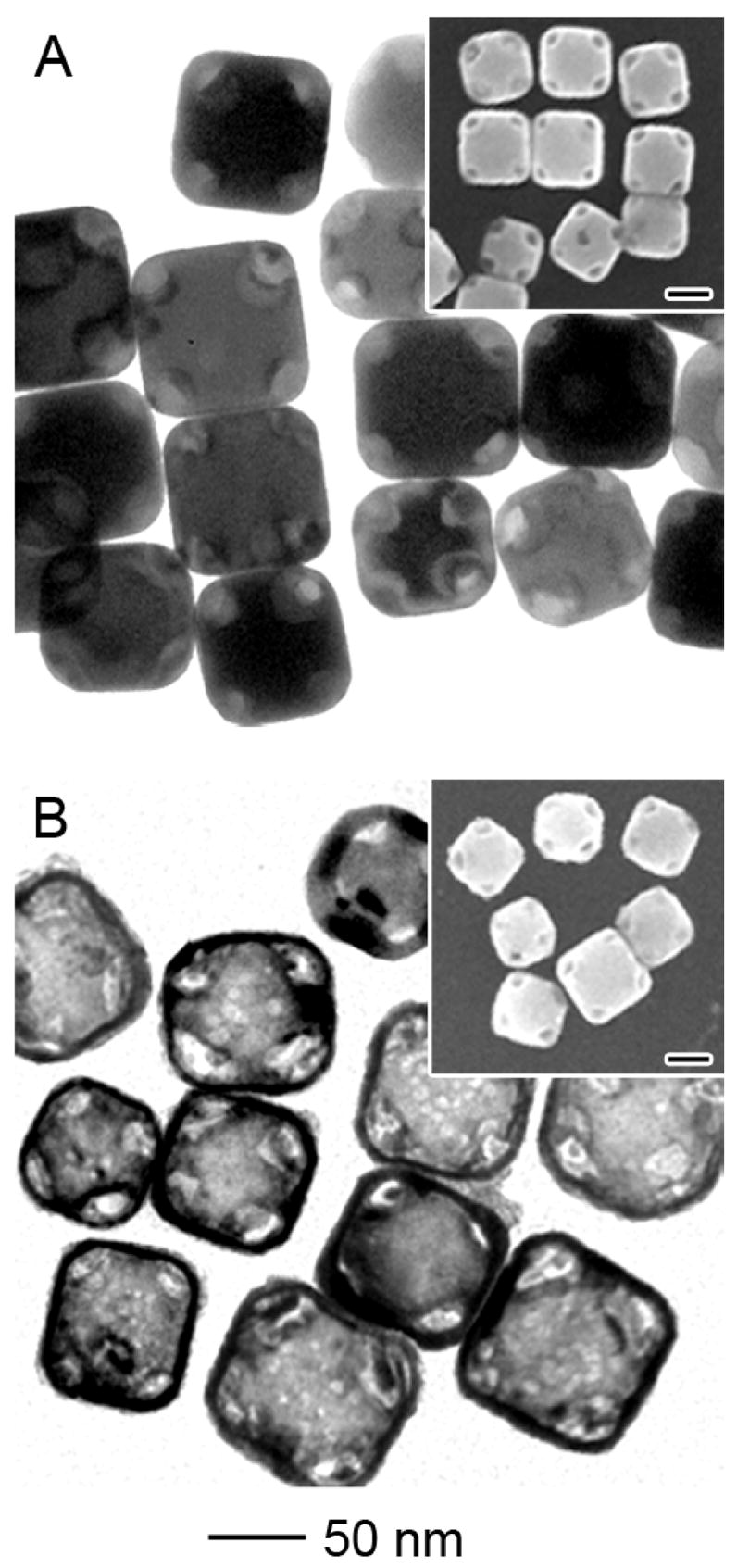

Figure 5.

TEM and SEM (insets) of 80-nm Au/Ag alloy nanocages obtained through the galvanic replacement reaction between corner-truncated Ag nanocubes and HAuCl4, followed by etching with Fe(NO3)3 solution. (A) When reacted with 0.8 mL of 0.2 mM HAuCl4 solution, the truncated Ag nanocubes were converted into nanoboxes with openings at the corners. (B) After etching with 5 μL of 50 mM Fe(NO3)3 solution, the wall thickness of the nanoboxes was significantly reduced while the shape profile and the openings at the corners were well preserved. The scales bars for all insets are 50 nm.

In addition to Fe(NO3)3, aqueous NH4OH solution could also be used to dissolve the Ag from Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes. Murphy and co-workers recently reported that etching of Au/Ag bimetallic nanowires with an NH4OH solution could form Ag nanotubes.11b The dissolution of Ag with concentrated NH4OH solution in the presence of oxygen is due to the formation of a water soluble complex [Ag(NH3)2]+. In the present work, we tested Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes with two different sizes that were fabricated by reacting 50- and 80-nm Ag nanocubes with HAuCl4. Both samples were then reacted with 2 mL NH4OH solution for 12 hours (Figure S3). The 50-nm nanoboxes are the same as those shown in Figure 2B, with a Au to Ag atomic ratio of 15:85. Unlike the etching with Fe(NO3)3 solution, which eventually produced cubic nanoframes at a high yield, both TEM and SEM show that etching with NH4OH solution resulted in a mixture of nanocages and nanoframes (Figure S3). For the 80-nm nanoboxes (Figure S3B), they were prepared by reacting 80-nm Ag nanocubes with 8 mL of 0.2 mM HAuCl4 solution. The Au to Ag atomic ratio was 20:80 as indicated by EDX. Similar to the 50-nm nanoboxes, the 80-nm nanoboxes were also converted into a mixture of cubic nanoframes and nanocages (Figure S3C) after they had been reacted with the NH4OH solution. The different morphologies observed for Fe(NO3)3 and NH4OH solutions probably arose from the difference in etching kinetics. As NH4OH is a much weaker enchant than Fe(NO3)3,11a Au atoms can diffuse and passivate the remaining Au/Ag alloy surface before the Ag atoms are completely removed with NH4OH. In addition, the dissolution rate of Ag in an NH4OH solution is dependent on the supply of oxygen, which can limit the uniformity of the products due to the variation of dissolution and diffusion of oxygen in water during the etching process. Based on these arguments, Fe(NO3)3 seems to be a better etchant than NH4OH for converting Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes into Au nanocages and then cubic nanoframes.

In summary, we have investigated the selective removal (or dealloying) of Ag atoms from Au/Ag alloy nanoboxes with an aqueous etchant based on Fe(NO3)3 or NH4OH. Different from the previously reported protocols that use HAuCl4 for both the galvanic replacement reaction and the dealloying of Ag, there is no concurrent deposition of Au in the dealloying process when HAuCl4 is replaced with Fe(NO3)3 or NH4OH. This new procedure allows for a better control of the wall thickness and porosity for the resultant nanocages, as well as fabrication of new types of nanostructures such as cubic nanoframes. Although we have mainly focused on Fe(NO3)3 and NH4OH in this work, we believe other wet echants for silver metal11a can also be applied to the dealloying process in an effort to fine tune the wall thickness, porosity, pore size, and optical properties associated with the nanocages.

Supplementary Material

Detailed descriptions of materials and methods, as well as additional absorbance spectra and SEM/TEM images of the samples prepared under other conditions. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Director’s Pioneer Award from the NIH (1DP0D000798) and a research grant from the NSF (DMR-0451788). Y.X. is a Camille Dreyfus Teacher Scholar (2002–2007). X.L. is an INEST Postdoctoral Fellow supported by the Philip Morris USA. L.A. thanks the Center for Nanotechnology at the UW for an IGERT Fellowship funded by the NSF and NCI. This work used the Nanotech User Facility (NTUF) at the UW, a member of the National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (NNIN) funded by the NSF.

References

- 1.a) Sun Y, Xia Y. Science. 2002;298:2176. doi: 10.1126/science.1077229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sun Y, Mayers B, Xia Y. Adv Mater. 2003;15:641. [Google Scholar]; c) Wiley BJ, Sun Y, Chen J, Cang H, Li ZY, Li X, Xia Y. MRS Bull. 2005;30:356. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.003048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yang J, Lee JY, Too HP. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:19208. doi: 10.1021/jp052242x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Chen J, McLellan JM, Siekkinen A, Xiong Y, Li ZY, Xia Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14776. doi: 10.1021/ja066023g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Yin Y, Erdonmez C, Aloni S, Alivisatos AP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12671. doi: 10.1021/ja0646038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SW, Kim M, Lee WY, Hyeon T. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7642. doi: 10.1021/ja026032z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun Y, Xia Y. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5297. doi: 10.1021/ac0258352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portney NG, Ozkan M. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;384:620. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Chen J, Saeki F, Wiley BJ, Cang H, Cobb MJ, Li ZY, Au L, Zhang H, Kimmey MB, Li X, Xia Y. Nano Lett. 2005;5:473. doi: 10.1021/nl047950t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen J, Wiley BJ, Li ZY, Campbell D, Saeki F, Cang H, Au L, Lee J, Li X, Xia Y. Adv Mater. 2005;17:2255. [Google Scholar]; c) Cang H, Sun T, Li ZY, Chen J, Wiley BJ, Xia Y, Li X. Opt Lett. 2005;30:3048. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.003048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Loo C, Lin A, Hirsch L, Lee MH, Barton J, Halas N, West J, Drezek R. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2004;3:33. doi: 10.1177/153303460400300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen J, Wang D, Xi J, Au L, Siekkinen A, Warsen A, Li ZY, Zhang H, Xia Y, Li X. Nano Lett. 2007;ASAP doi: 10.1021/nl070345g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hirsch LR, Gobin AM, Lowery AR, Tam F, Drezek RA, Halas NJ, West JL. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34:15. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-9001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Wiley BJ, McLellan J, Xiong Y, Li ZY, Xia Y. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2058. doi: 10.1021/nl051652u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Xia Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3892. doi: 10.1021/ja039734c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi YU, Lee EC, Han KN. Metallurgical Trans B Proc Metallurgy. 1991;22:755. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Martinez L, Segarra M, Fernandez M, Espiell F. Metallurgical Trans B Proc Metallurgy. 1993;24:827. [Google Scholar]; b) Dursun A, Pugh DV, Corcoran SG. J Electrochem Soc. 2003;150:B355. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Xia Y, Kim E, Whitesides GM. J Electrochem Soc. 1996;143:1070. [Google Scholar]; b) Hunyadi SE, Murphy CJ. J Mater Chem. 2006;16:3929. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Im SH, Lee YT, Wiley BJ, Xia Y. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2005;44:2154. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlebacher J, Aziz MJ, Karma A, Dimitrov N, Sieradzki K. Nature. 2001;410:450. doi: 10.1038/35068529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed descriptions of materials and methods, as well as additional absorbance spectra and SEM/TEM images of the samples prepared under other conditions. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.