Abstract

The term peripheral auditory compression refers to the fact that the whole range of audible sound pressure levels is mapped into a narrower range of auditory nerve responses. Peripheral compression is the by-product of independent compressive processes occurring at the level of the basilar membrane, the inner hair cell (IHC), and the auditory nerve synapse. Here, an electrical-circuit equivalent of an IHC is used to look into the compression contributed by the IHC. The model includes a mechanically driven transducer potassium (K+) conductance and two time- and voltage-dependent basolateral K+ conductances: one with fast and one with slow kinetics. Special attention is paid to faithfully implement the activation kinetics of these basolateral conductances. Optimum model parameters are provided to account for previously reported in vitro observations that demonstrate the compression associated with the gating of the transducer and of the basolateral channels. Without having to readjust its parameters, the model also accounts for the in vivo nonlinear IHC transfer characteristics. Model simulations are then used to investigate the relative contribution of the transducer and basolateral K+ currents to the nonlinear IHC input/output functions in vivo. The simulations suggest that the voltage-dependent activation of the basolateral currents compresses the DC potential for stereocilia displacements above approximately 5 nm. The degree of compression exceeds 2-to-1 and is similar for all stimulation frequencies. The AC potential is compressed in a similar way, but only for frequencies below 800 Hz. The simulations further suggest that the nonlinear gating of the transducer current is responsible for the expansive growth of the DC potential with increasing sound level (slope of 2 dB/dB) at low sound pressure levels.

Keywords: inner hair cell, biophysical model, potassium currents, peripheral compression, auditory nonlinearity, DC, AC, receptor potential

Introduction

A system is said to be compressive when the increase in the magnitude of its output is less than the associated increase in the magnitude of its input. The peripheral auditory system is compressive, as the range of audible sound pressure levels (SPLs) is mapped into a narrower range of auditory nerve discharge rates. Several nonlinear processes contribute to peripheral compression. Basilar membrane motion, inner hair cell (IHC) transduction, and the release of neurotransmitter from the IHC are the most important, and they all influence auditory perception (Cooper 2004; Lopez-Poveda 2005; Bacon et al. 2004). The purpose of this work is to investigate the origin of the compression contributed by the IHC.

Inner hair cells are responsible for the mechanoelectrical transduction in the organ of Corti of the mammalian cochlea. Deflection of their stereocilia bundles modulates the flow of ions into the cells and thus causes fluctuations of their intracellular voltage. Potassium (K+) is the major carrier of the transducer current. The “excess” of intracellular potassium that may result from bundle deflections is eliminated through K+ channels found in the IHC basolateral membrane, whose conductance depends on the IHC basolateral transmembrane potential (Kros and Crawford 1990). Therefore, the intracellular voltage variations produced by transducer currents may be modulated by the currents flowing through these voltage-dependent basolateral K+ conductances.

The compressive transfer characteristics of the IHC reflect two nonlinearities at least. One of them relates to the saturation of the transducer current at high levels and is reasonably well known and acknowledged (e.g., Lukashkin and Russell 1998). The other relates to the basolateral K+ conductances and is less acknowledged (reviewed by Dallos 1996 and Kros 1996).

The role of basolateral K+ currents (IK) in modulating the IHC potential was investigated by Kros and Crawford (1990). They showed that in response to injections of large depolarizing current pulses, aiming to simulate steps of transducer currents, the time course of the membrane potential shows a form of adaptation. That is, it is larger at the beginning of the current pulse and declines progressively as time evolves until it reaches a steady-state value. They also showed that the membrane potential increases in a nonlinear compressive manner as a function of the magnitude of the injected current. Kros and Crawford (1990) attributed these two results to the time and voltage dependence of activation of the basolateral K+ currents, respectively.

The conclusions of Kros and Crawford (1990) were based on their analysis of the response of isolated IHCs to current injection, but it is yet to be confirmed that they also apply to in vivo situations. Furthermore, it is unknown to what extent the compression contributed by the voltage-dependent basolateral K+ currents adds to that caused by the saturation of the transducer current, or how it depends on the stimulus frequency. The specific aim of this work is to investigate these issues using a biophysical model of the IHC.

Biophysical IHC models that include time- and voltage-dependent basolateral K+ currents were rare until recently (a review of earlier models is provided by Mountain and Hubbard 1996). Only one model of that kind was available before the start of this work (Van Emst et al. 1997), and one more was published during its course (Zeddies and Siegel 2004). Van Emst et al. developed their model mainly to assess the contribution of basolateral K+ currents to the summating potential, whereas Zeddies and Siegel used their model to investigate the homeostatic mechanisms responsible for the resting potential of the IHC. Neither of these two studies assessed the contribution of basolateral K+ currents to the IHC nonlinear input/output transfer characteristics measured in vitro or in vivo, or compared their models' performance against relevant experimental data. Another aim of this work is to provide an alternative, simpler model that addresses these issues. Special attention is dedicated to develop a general expression for computing the time course of activation of the basolateral K+ conductances for any time course of the membrane potential.

In the following sections, it is shown that the proposed model accounts for a wide range of well-reported in vitro and in vivo IHC response characteristics without a need for readjusting its parameters across data sets. Model simulations support that the basolateral K+ conductances do apply compression in vivo and effectively reduce the rate of growth of IHC potential with increasing stereocilia displacement by more than a factor of 2 for displacements above approximately 5 nm. Such compression affects the DC component of the cell's potential in a similar way for all stimulation frequencies. The AC component is equally affected but only for stimulation frequencies below 800 Hz. The simulations further suggest that the nonlinear gating of the transducer current produces an expansive growth of the DC potential with increasing the sound level (slope of 2 dB/dB) at low SPLs.

Methods

Our approach was to produce a biophysical model of the IHC that reproduces the in vitro results of Kros and Crawford (1990) described in Introduction. This allowed obtaining a set of optimum parameters to account for the time and voltage dependence of the basolateral K+ conductances. The same parameters were then used to run in vivo simulations with two purposes: (1) to demonstrate that the model is adequate to reproduce well-reported in vivo data; and (2) to compare the receptor potential in a simulated in vivo condition where the activation of basolateral K+ conductances is explicitly made constant against a corresponding condition where it is made time- and voltage-dependent. Such comparison serves to determine the contribution of the voltage-dependent character of basolateral K+ currents to the nonlinear compressive aspect of IHC input/output functions in vivo.

The model

The present model is similar in structure to many IHC models (reviewed by Mountain and Hubbard 1996). It assumes that the IHC receptor potential is primarily controlled by the interplay of a transducer (inward) K+ current that results from stereocilia deflections and two basolateral (outward) K+ currents that eliminate the excess of K+ from within the IHC (Kros and Crawford 1990). In other words, the present model attributes the net conductance of the IHC membrane to K+ ions only. The explicit contribution of other ions (e.g., Na2+ or Cl−) to the total IHC conductance (reviewed by Kros 1996) is omitted.

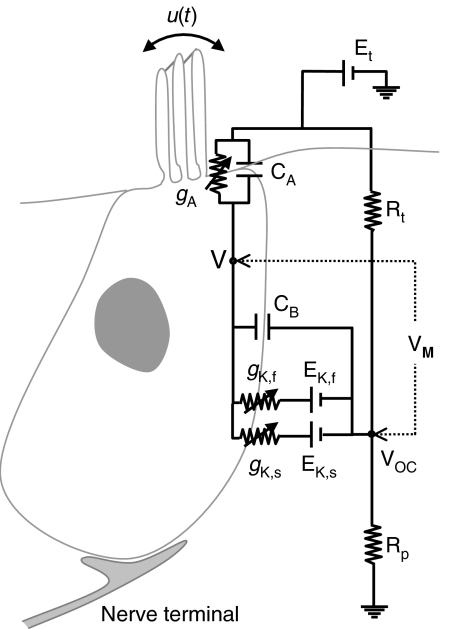

The model electric-circuit structure, assuming an in vivo situation, is depicted in Figure 1. It resembles the structure proposed by Shamma et al. (1986), which itself derives from the hair cell-epithelium equivalent circuit of Corey and Hudspeth (1983). It consists of several elements that describe the electrical properties of the apical and the basal portions of the IHC membrane and its surrounding fluids. gA represents the apical conductance (described in the following section). gK,f and gK,s represent the voltage-gated fast and slow components of the basolateral K+ conductance described by Kros and Crawford (1990), and EK,f and EK,s are the reversal potentials of their respective associated currents. Et represents the endocochlear potential, and Rt and Rp are the epithelium resistances. CA and CB represent the capacitance of the apical and basal portions of the IHC membrane. The model assumes that the IHC intracellular space is equipotential and thus can be represented by a single node V (Dallos 1983). Here, the membrane potential VM is considered as the intracellular minus the extracellular potentials; that is, VM = V − VOC according to the circuit of Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Model diagram: electrical equivalent circuit of the cell. Et = Endocochlear potential; Rt, Rp = epithelium resistances. CA, CB = Capacitance of the apical and basal portions of the cell's membrane, respectively. gA = Conductance of the apical portion of the cell's membrane; it is assumed to be the sum of a mechanically sensitive K+ conductance gm(u) and a leakage conductance gL (not shown). gK,f, and gK,s = Fast and slow basolateral K+ conductances. EK,f, and EK,s = Reversal potentials of the fast and slow basolateral K+ conductances. u = Stereocilia displacement. V = Inner hair cell intracellular potential. VOC = Extracellular potential. VM = Membrane potential, defined as V−VOC.

The apical conductance

The apical conductance gA is expressed as the sum of two conductances: the mechanical, transducer conductance gm and a leakage conductance gL. The mechanical conductance is assumed to depend on IHC stereocilia displacement (u). The work of Kros et al. (1992) for neonatal mice suggests that the gating process underlying transduction may be described as a three-state Boltzmann function and thus:

|

1 |

where GM is the maximum mechanical conductance (i.e., the conductance with all transducer channels fully open), s0 and s1 are the displacement sensitivity parameters, and u0 and u1 are the displacement offset parameters.

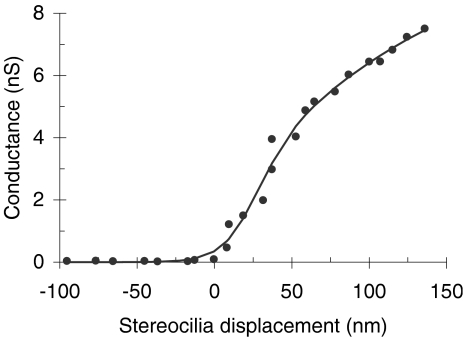

For the in vivo model evaluations, parameters GM, s0, s1, u0, and u1 were optimized so that Eq. (1) fits the experimental transducer conductance data of Kros et al. (1995) as shown in Figure 2. The value of these parameters (Table 1) remained the same throughout all in vivo evaluations. Although the data in Figure 2 correspond to outer hair cells (OHCs) rather than IHCs, Kros (1996, p. 238) has argued that the transducer conductance is probably similar for both hair-cell types. The leakage conductance (gL) was regarded as constant and was a free parameter of the model (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Dependence of the apical mechanical conductance on stereocilia displacement. Points illustrate experimental data for an OHC of the neonatal mice (adapted from Figure 5 of Kros et al. 1995). The continuous line illustrates the actual function used in the model [i.e., Eq. (1) with the parameters shown in Table 1].

Table 1.

Model parameters and associated resting potentials

| In vitro | In vivo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast | Slow | |||

| Pressure-to-cilia displacement scaling factor (m/Pa) | k | 200E−9 | ||

| Endocochlear potential (V) | Et | −4E−3 | −4E−3 | 100E−3 |

| Epithelium resistance (Ω) | Rp | 0.01 | ||

| Epithelium resistance (Ω) | Rt | 0.24 | ||

| Apical conductance (S) | gA | 2.83E−10 | 2.21E−10 | gm(u) + gL |

| Apical leakage conductance (S) | gL | 0.33E−9 | ||

| Apical mechanical conductance | gm(u) | |||

| Maximum value (S) | GM | 9.45E−9 | ||

| Displacement sensitivity (m−1) | s0 | 63.1E−9 | ||

| Displacement sensitivity (m−1) | s1 | 12.7E−9 | ||

| Displacement offset (m) | u0 | 52.7E−9 | ||

| Displacement offset (m) | u1 | 29.4E−9 | ||

| Apical capacitance (F) | CA | 0.89E−12 | 0.89E−12 | 0.89E−12 |

| Basal capacitance (F) | CB | 6.00E−12 | 8.74E−12 | 8.0E−12 |

| Fast-conductance parameters | gK,f | |||

| Reversal potential (V) | EK,f | −78E−3 | −78E−3 | |

| Maximum conductance (S) | GF | 30.72E−9 | 30.72E−9 | |

| Half-activation potential (V) | V1,f | −43.20E−3 | −43.20E−3 | |

| Voltage sensitivity constant (V) | S1,f | 11.99E−3 | 11.99E−3 | |

| Half-activation potential (V) | V2,f | −64.20E−3 | −64.20E−3 | |

| Voltage sensitivity constant (V) | S2,f | 9.6E−3 | 9.6E−3 | |

| Time constants (s) | τ1max,f | 0.33E−3 | 0.33E−3 | |

| A1,f | 31.25E−3 | 31.25E−3 | ||

| B1,f | 5.42E−3 | 5.42E−3 | ||

| τ1min,f | 0.10E−3 | 0.10E−3 | ||

| τ2max,f | 0.1E−3 | 0.1E−3 | ||

| A2,f | 1E−3 | 1E−3 | ||

| B2,f | 1E−3 | 1E−3 | ||

| τ2min,f | 0.09E−3 | 0.09E−3 | ||

| Slow-conductance parameters | gK,s | |||

| Reversal potential (V) | EK,s | −75E−3 | −75E−3 | |

| Maximum conductance (S) | GS | 28.71E−9 | 28.71E−9 | |

| Half-activation potential (V) | V1,s | −52.22E−3 | −52.22E−3 | |

| Voltage sensitivity constant (V) | S1,s | 12.66E−3 | 12.66E−3 | |

| Half-activation potential (V) | V2,s | −85.22E−3 | −85.22E−3 | |

| Voltage sensitivity constant (V) | S2,s | 16.9E−3 | 16.9E−3 | |

| Time constants (s) | τ1max,s | 9.90E−3 | 9.90E−3 | |

| A1,s | 15.27E−3 | 15.27E−3 | ||

| B1,s | 7.27E−3 | 7.27E−3 | ||

| τ1min,s | 1.3E−3 | 1.3E−3 | ||

| τ2max,s | 4.27E−3 | 4.27E−3 | ||

| A2,s | 48.20E−3 | 48.20E−3 | ||

| B2,s | 8.72E−3 | 8.72E−3 | ||

| τ2min,s | 0.01E−3 | 0.01E−3 | ||

| Resting membrane potential (V) | VMrest | −67E−3 | −72E−3 | −60E−3 |

For the in vitro model evaluations, gL did not apply and neither did Eq. (1), as no hair bundle stimulation was used in the experiments discussed (membrane currents and/or voltage were manipulated electrophysiologically). Instead, the total apical conductance gA was regarded as constant and was a free parameter of the model.

Basolateral K+ conductances

Kros and Crawford (1990) described two types of time- and voltage-dependent basolateral K+ outward currents in response to depolarizing voltage steps: one that developed very fast and could be selectively blocked by extracellular tetraethylammonium (TEA), and one that developed more slowly and could be selectively blocked by 4-aminopyridine (4-AP). Although additional K+ currents may exist in IHCs (see Discussion), they are omitted in this model. Therefore, here, the total basolateral conductance gK(t, VM) is expressed as the sum of two independent conductances, which will be hereinafter referred to as fast (gK,f) and slow (gK,s). The validity of this approximation and its implications are discussed in the following text.

Kinetics of the fast and slow channels

Kros and Crawford (1990) showed that when a voltage step is applied to the IHC membrane, the time course of both the fast and slow K+ currents can be reasonably fitted, at least for low-to-moderate depolarizations, by an equation of the form:

|

2 |

where I0 is the value of the current before the voltage step is applied,  is the current at time infinity after the voltage step is applied, and τ1 (VM) and τ2 (VM) are two voltage-dependent time constants.

is the current at time infinity after the voltage step is applied, and τ1 (VM) and τ2 (VM) are two voltage-dependent time constants.

Equation (2) provides an analytical solution for a particular time course of the membrane potential, namely, a voltage step, and channel activation is a nonlinear process. Therefore, Eq. (2) cannot be used to estimate the time course of the fast and slow current components for an arbitrary time course of the membrane potential, as is required for a general-purpose model. On the other hand, Eq. (2) describes the behavior of a channel with two closed states and one open state (Kros and Crawford 1990). The Appendix shows that the following second-order differential equation describes the time course of the macroscopic current flow through such a system:

|

3 |

A corresponding expression may be derived for the channel conductance g instead of the current i by equating i = g(VM − EK), with EK being the reversal potential.

Kros and Crawford (1990) also showed that both time constants τ1 and τ2 are temperature- and voltage-dependent (see their Fig. 12). In the model, the same temperature was assumed for all evaluations (∼35–36°C), and the following ad hoc functions were used to account for the voltage dependence of the time constants:

|

4.1 |

|

4.2 |

where A1, A2, B1, B2, and the minimum and maximum values of each of the two time constants are model parameters (Table 1), and their values are assumed fixed for any given temperature.

Equations (3), (4.1), and (4.2), with corresponding parameters (Table 1), were employed to model the time course of gK,f and gK,s.

Steady-state activation of the fast and slow channels

The steady-state activation of both gK,f and gK,s also depends on the membrane potential. Kros and Crawford (1990) argued that the activation curve of gK,s was adequately described by a first-order Boltzmann function, whereas that of gK,f would be better described by a Boltzmann function of a higher order. Given that the time course of activation of both fast and slow conductances approximates reasonably well to that of a three-state system [Eq. (2)], it seems more reasonable that the voltage dependence of activation of both channels be described by a second-order Boltzmann function. Therefore, the following expression was used to implement the steady-state voltage-dependent activation of the fast conductance:

|

5 |

where VM represents the membrane potential, GF is the maximum fast conductance (i.e., assuming that all of the fast K+ channels are fully opened), and V1,f, V2,f, S1,f, and S2,f are model parameters. A function identical to Eq. (5) (not shown) with corresponding parameters (GS, V1,s, V2,s, S1,s, and S2,s) was employed to account for the voltage-dependent activation of gK,s.

In vitro and in vivo model configurations

Two different model configurations were considered to replicate in vitro and in vivo conditions.

In vitro configuration

It was designed to reproduce the in vitro experiments of Kros and Crawford (1990). In those experiments, IHCs were isolated from the cochlea and bathed in an assumingly equipotential extracellular salty solution held at a constant reference potential. These conditions were simulated with the electrical circuit of Figure 1 by letting Et represent the reference potential of the extracellular solution and setting Rt = 0, and thus VOC = Et. Furthermore, assuming that the IHC stereocilia were steady during the experimental recordings, the total apical conductance gA was made constant in the model.

This configuration was used to replicate specifically the experiment of Kros and Crawford (1990) where the time course of the membrane potential was measured in response to constant-current pulses passed through the membrane. This experiment was simulated by applying constant-current pulses at node V of Figure 1. By applying Kirchoff's laws to the circuit of Figure 1, it can be easily shown that, in this case, the following equation relates the membrane potential VM = V − VOC and the net current applied iP:

|

6 |

Equation (6) was also used to predict the time course of the intracellular potential for injected current with half-wave rectified waveforms (see below).

In vivo configuration

This configuration was used to simulate variations of the IHC intracellular potential in response to stereocilia deflections. Therefore, the model input was a time-varying signal u(t) that represents the amplitude of stereocilia oscillations with respect to their resting position. The model was just as depicted in Figure 1. It resembles that of Shamma et al. (1986), except that the basolateral conductance here explicitly includes two time- and voltage-dependent components, gK,f and gK,s, instead of just one constant component, as considered by Shamma et al. Consequently, an adapted version of Eq. (13) of Shamma et al. (1986) was used here to relate the intracellular potential to stereocilia displacement. The equation is as follows:

|

7 |

where  . gK,f and gK,s were calculated as for the in vitro configuration (see the previous section). The main novelty of this equation, with respect to that of Shamma et al. (1986), is that it accounts for the effects of gK,f and gK,s separately.

. gK,f and gK,s were calculated as for the in vitro configuration (see the previous section). The main novelty of this equation, with respect to that of Shamma et al. (1986), is that it accounts for the effects of gK,f and gK,s separately.

In deriving Eq. (7), it was assumed (cf. Shamma et al. 1986) that the resistance of the pathway through the IHC membrane from the endolymph of the scala media to the perilymph of the scala tympani is much larger than that through the epithelium, i.e., 1/Rt ≫ gK,f, gK,s (Corey and Hudspeth 1983). Consequently, the extracellular potential VOC is approximately constant, and it was treated as such in the model.

Model implementation

The model was implemented and evaluated digitally in the time domain using Matlab™ (release 12). The sampling rate was 44,100 Hz throughout the evaluations. The code is available from authors on request.

Model parameters

Table 1 lists the model parameters and their values, which were obtained as follows.

Because the aim of this work was to determine the contribution of voltage-gated basolateral K+ currents to the nonlinear transfer characteristics of the IHC, and given that the nonlinear contribution of these currents was first described by Kros and Crawford (1990), special attention was paid to obtaining an optimum set of parameters for reproducing the data of Kros and Crawford. Specifically, the parameters were optimized to account for the observed time course of the membrane potential in response to K+ current pulses passed through the membrane (Figs. 13 and 14 of Kros and Crawford 1990). Two versions of the in vitro model were used to replicate two corresponding experimental conditions. One considered that only the slow K+ channels were operative and that the fast channels were fully blocked with TEA. This condition was simulated by setting GF = 0 in the model and was used to optimize the parameters that control gK,s. The resulting parameter set is shown under the “slow” column in Table 1. Another model version considered that only the fast K+ channels were operative, and that the slow channels were fully blocked with 4-AP. This condition was simulated by setting GS = 0 and was used to optimize the parameters of gK,f. The resulting parameter set is shown under the “fast” column in Table 1. The functioning of a control cell, i.e., a cell with the fast and slow K+ channels fully operative, was simulated using these “fast” and “slow” parameter sets simultaneously.

To demonstrate the usefulness of the model, its performance was compared against a wide range of in vivo experimental data sets. These came from different cells studied in the same laboratory or even from studies carried out in different laboratories. Therefore, the data considered probably reflect some variability in cell size and/or experimental conditions. To optimally reproduce the different data sets while allowing for such variability, the total cell capacitance (CA + CB) and the maximum values of the model conductances (GM, gL, GF, and GS) were adjusted if necessary from the values of Table 1. The optimum values of these parameters are reported when appropriate in the following text. All other parameters remained the same through the different model evaluations.

Model performance

In vitro response to the injection of current pulses

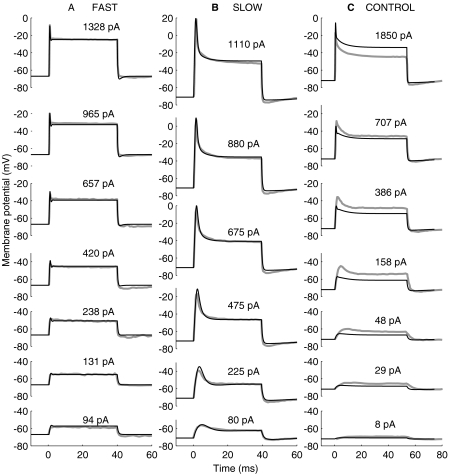

Kros and Crawford (1990) investigated the effects of IK,f and IK,s on the membrane potential by passing constant-current pulses through the membrane. Figure 3 illustrates their results (thick gray lines) compared with the responses of a corresponding in vitro configuration of the model (thin black lines). The figure illustrates the time course of the membrane potential for current pulses of different magnitudes, as indicated by the numbers next to each trace, and for three conditions: a cell with IK,s blocked with 4-AP (Fig. 3A), a cell with IK,f blocked with TEA (Fig. 3B), and a control cell (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Experimental (thick, gray lines) and model (thin, black lines) voltage responses to injection of depolarizing currents. The experimental data were adapted from Figure 13 of Kros and Crawford (1990). The current pulses start at time zero, and their magnitudes are indicated in units of pA by the numbers next to each trace. (A) Responses for a cell whose slow channels were blocked with 4-AP. The resting potential was −72 mV both for the model and the experimental cells. The model was evaluated with the parameters under the fast column of Table 1. (B) Responses for a cell whose fast channels were blocked with TEA. The resting potential was −67 mV both for the model and the experimental cells. The model was evaluated with the parameters under the slow column of Table 1. (C) Responses for a control cell. The resting potential was −71 mV for the model cell and unspecified for the experimental cell. The model parameters for the fast and slow basolateral conductances were those under the in vivo column of Table 1, except for gA, which was set to 0.22 nS.

Let us compare first the model and experimental responses for the cases where either IK,s or IK,f were blocked independently (Fig. 3A and B, respectively). Clearly, the model reproduces most features of the experimental responses. The model resting membrane potentials are identical to the physiological values (−67 and −71 mV for Fig. 3A and B, respectively). The model also reproduces that the membrane potential increases suddenly to a peak value immediately after the current-pulse onset and later decays to a lower, steady-state value, the decay being faster when IK,s is blocked (Fig. 3A) than when IK,f is blocked (Fig. 3B). The model even shows a hint of the damped oscillations that occur in the experimental data right after the onset peak when IK,s is blocked (Fig. 3A), but not when IK,f is blocked (Fig. 3B), consistent with the observations of Kros and Crawford (1990). The major discrepancy between the model and the experimental responses occurs right after the current-pulse offset. At this time, the experimental membrane potential appears slightly more hyperpolarized than the model one, particularly when IK,f is blocked (Fig. 3B).

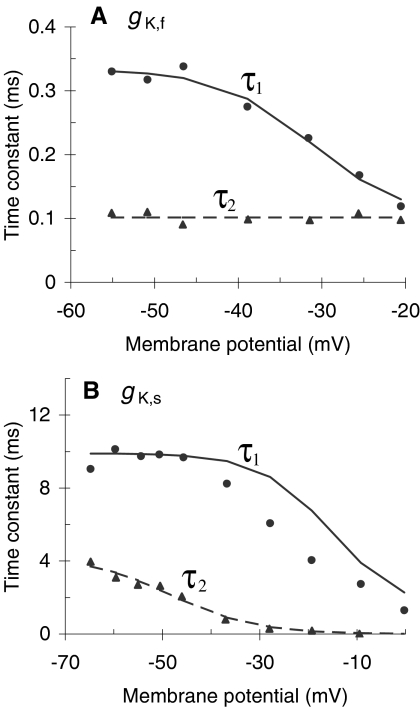

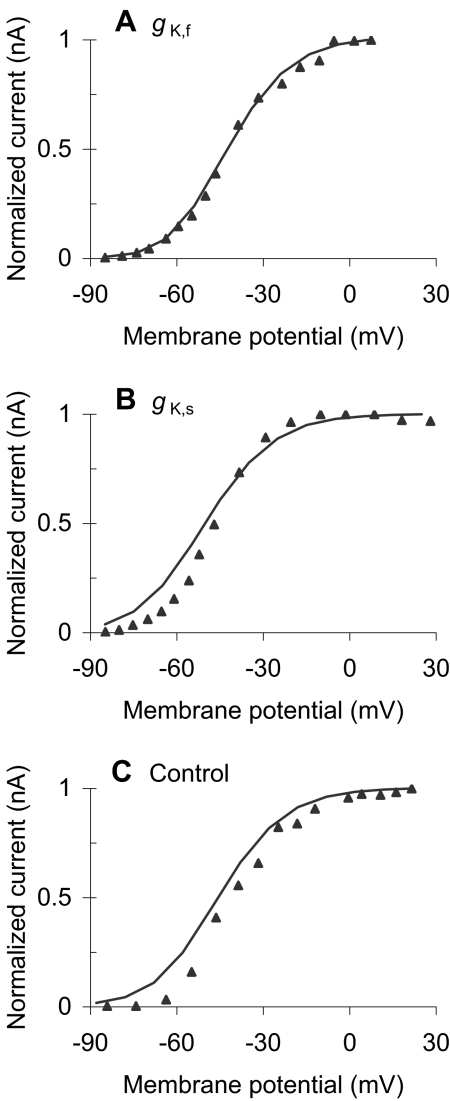

The parameters required to produce this rather realistic model responses are within (or very close to) physiological limits (Table 1). Figure 4 shows, for instance, that the values of the model time constants (lines) closely approximate those reported by Kros and Crawford (1990) for a temperature around 35–36°C (symbols). The main deviation of the model with respect to the experimental values occurs for τ1 of IK,s. Such deviation seems, however, reasonable considering that time constants are extremely sensitive to temperature and that the experimental data of Figures 3 and 4 may be for different IHCs or were obtained at slightly different temperatures. Likewise, Figure 5A and B shows that the model activation curves of IK,f and IK,s, respectively, are reasonably similar to those reported by Kros and Crawford (1990). Note that the ordinates illustrate normalized current values. This aims to facilitate the comparison allowing for differences in total cell conductance that might occur because the experimental activation curves are not for the same IHC for which the model parameters were optimized. This justifies that the normalization factors (shown in the caption of Fig. 5) be different for the model and the experimental activation curves. Finally, the total cell capacitance of the model, CA + CB (Table 1), is also close to the experimental range of 9.6 ± 2.0 pF (mean ± SD) reported by Kros and Crawford (1990).

Fig. 4.

Voltage dependence of the time constants τ1 and τ2 for the fast (A) and slow (B) basolateral K+ conductances. Symbols illustrate experimental data for a temperature of 35–36°C [adapted from Figure 12(A) and (C) of Kros and Crawford 1990). Lines are not best fits to the data. They represent the dependence required for the model to simulate the data of Figure 3A and B [i.e., Eqs. (4.1) and (4.2) with the parameters of Table 1]. The same dependence was used to produce all other model results.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of experimental (symbols) and model (lines) normalized activation curves for the outward potassium currents. (A) Activation curve of the fast (4-AP resistant) potassium current. The normalization factors are 1.03 and 0.93 for the experimental and modeled curves, respectively. (B) Activation curve for the slow (TEA-resistant) potassium current. The normalization factors are 0.59 and 0.83 for the experimental and modeled curves, respectively. (C) Activation curve for a control cell. The normalization factors are 3.67 and 2.27 for the experimental and modeled curves, respectively. The experimental data of panels A–C were adapted from Figures 10B, 8B, and 4B of Kros and Crawford (1990), respectively. Note that the lines do not represent second-order Boltzmann best fits to the experimental curves. Instead, they illustrate the activation curves of the model with the parameters required to account for the experimental data of Figure 3A and B.

Let us now compare the model and the experimental responses for a control cell (Fig. 3C). In this case, the model was evaluated considering that both gK,f and gK,s were operative and identical to those used to reproduce the results shown so far; thus, the “fast” and “slow” in vitro parameter sets of Table 1 were used simultaneously. gA was set to 0.22 nS to achieve the resting membrane potential of the experimental cell (−72 mV; Kros and Crawford 1990). CB was set to a value of 8 pF, identical to the value that will be used later for the in vivo evaluations. The model response is comparable in shape to the experimental response (Fig. 3C). That is, the model produces an adapting response where the onset peak gets more pronounced as the amplitude of the injected current pulse increases. On the other hand, the model fails to account for the amplitude of the experimental response. The membrane potential is lower in the model than in the experimental responses when the amplitude of the injected current is less than 707 pA (or, correspondingly, when the membrane potential is below approximately −40 mV; see Fig. 3C), and higher otherwise. This suggests that the total outward current is greater in the model than in experimental cell when the membrane potential is below −40 mV, and smaller otherwise. This result possibly relates to the differences between the activation curves of the model and the experimental cells (Fig. 5C).

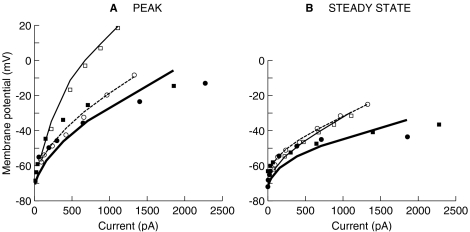

Based on the experimental responses reproduced in Figure 3, Kros and Crawford (1990, p. 285) concluded that the two basolateral K+ currents cause the membrane potential to increase compressively, rather than linearly, with increasing the amount of injected current. This result is illustrated more clearly in Figure 6 (filled symbols), where the voltage values at the peak of the response (Fig. 6A) and at 37.3 ms after the current-pulse onset (Fig. 6B) are plotted against the amount of the injected current [data reproduced from Figure 14 of Kros and Crawford (1990)]. Clearly, the compressive growth is more evident when the voltage has stabilized (Fig. 6B), but also occurs at the response onset (Fig. 6A). That the compressive growth of the membrane potential is caused by the basolateral K+ currents may be concluded because the growth is more linear for cells that are either bathed in TEA (open square symbol) or filled with 4-AP (open circle symbol).

Fig. 6.

Nonlinear behavior of the IHC's membrane potential. Symbols illustrate experimental data adapted from Figure 14 of Kros and Crawford (1990); lines illustrate corresponding model responses. (A) Peak voltage responses. (B) Steady-state voltage responses. Filled symbols and thick continuous lines illustrate the responses for control cells. Open squares and thin continuous lines illustrate the responses for a cell whose fast components were blocked. Open circles and dashed lines illustrate the responses for cells whose slow components were blocked.

The model also reproduces this experimental behavior to a reasonable approximation. For a control cell (thick lines in Fig. 6), the voltage clearly increases compressively with increasing the amount of injected current, and compression is stronger during the steady state than at the peak of the response, consistent with the experimental observations. Quantitatively, though, the nonlinear effect is weaker (i.e., less compression occurs) for the model control cell than for the experimental one. By setting parameters GF or GS to zero, the model also accounts excellently for the experimental data of cells with their IK,f and IK,s blocked, both at the peak of the response and during the steady state (i.e., notice the precise match between the open symbols and the thin lines in Fig. 6).

In summary, using parameters within physiological ranges, the model reproduces to a reasonable approximation the behavior that led Kros and Crawford (1990) to suggest that the basolateral K+ currents impart a compressive nonlinearity on the membrane potential. The nonlinearity for a control cell is admittedly less pronounced in the model than in the data, and this will be taken into account when discussing the following results.

In vivo responses to sinusoidal stereocilia displacement

This section aims to demonstrate that the model is also valid to reproduce well-reported in vivo data, particularly data pertaining to IHC nonlinear input/output characteristics. To do it, the in vivo version of the model (Fig. 1) was used having stereocilia displacement as the input. Only sinusoidal displacement waveforms were considered. The parameter values under the in vivo column of Table 1 were used. Note that the values of the parameters that determine the characteristics of the basolateral K+ conductances remained identical with those used for the in vitro evaluations described in the preceding section.

Recordings of IHC responses in vivo are available in response to sound stimulation only, but not in response to direct stereocilia manipulation, as would be preferred here for direct model–data comparisons. Nevertheless, model responses to sinusoidal stereocilia displacement may still be directly compared against corresponding IHC responses to sound provided that the latter come from basal cells stimulated with low-frequency pure tones. In those cases, it is reasonable to assume that the basilar membrane responses are proportional to the acoustic pressure (evidence reviewed by Robles and Ruggero 2001), and that stereocilia displacement is proportional to basilar membrane displacement (at least for stimulation frequencies above around 300 Hz; see Nuttall et al. 1981). In short, in those cases, it may be assumed that the stereocilia displacement is approximately proportional (thus linearly related) to the acoustic pressure. The data described as follows meet those requirements, and a frequency-independent proportionality factor of 200 nm/Pa was used throughout to facilitate the model–data comparisons. (Note that basilar-membrane sensitivity is much greater for frequencies near the characteristic frequency (CF) of the IHC. Therefore, this proportionality factor is only approximately valid for stimulation frequencies well below the CF of the cell and may not be generalized to all frequencies. The issue is further discussed in Discussion).

Intracellular potential waveforms

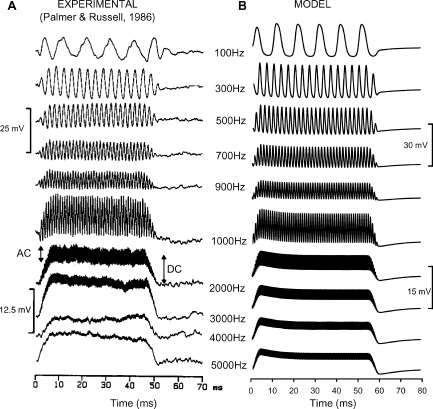

Figure 7 illustrates experimental intracellular receptor potential waveforms (from Palmer and Russell 1986; Fig. 7A) compared with model responses measured at node V of Figure 1 (Fig. 7B). Each horizontal pair of waveforms is for a different stimulation frequency, as indicated by the numbers in the middle column. The experimental and model waveforms were for tone bursts of 50 and 60 ms of duration, respectively. In both cases, the bursts had rise/fall ramps of 5 ms of duration. The experimental data were for an SPL of 80 dB (Palmer and Russell 1986), and so the model responses correspond to an equivalent stereocilia displacement of 40 nm (assuming the above-mentioned proportionality factor that converts pressure to stereocilia displacement).

Fig. 7.

Comparison of experimental (A) and model (B) IHC intracellular potential waveforms for stimuli of different frequencies (as indicated by the numbers in the middle column). The experimental waveforms were adapted from Figure 9 of Palmer and Russell (1986). The model was evaluated using the in vivo configuration. The upper scale bars are for the 100–900 Hz waveforms; the lower scale bars are for the 1000–5000 Hz waveforms. The resting potentials were −37 and −58 mV for the experimental and model cells, respectively.

The resting potential for the model (−60 mV) is lower than for the real cell (−37 mV). Furthermore, it is closer to the range of values reported in vitro (Kros and Crawford 1990; Gitter and Zenner 1990) than to in vivo values (Dallos 1985b). These discrepancies, however, are not shortcomings of the model. The impalement of the electrode in vivo probably creates a significant leak conductance that keeps the cell more depolarized than it normally is. Therefore, the actual resting potential in vivo is almost certainly lower than it has been reported and closer to in vitro values (Kros and Crawford 1990; Kros 1996; Zeddies and Siegel 2004), which agrees with the model prediction.

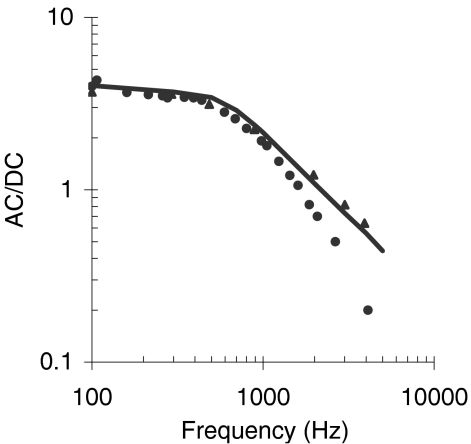

The model and the experimental waveforms have only slightly different amplitudes (compare scale bars) and similar shapes. The model responses to low-frequency tones are quasi-sinusoidal and asymmetrical with respect to the resting potential, consistent with the data. As the frequency of the stimulus is progressively increased, the model responses become more asymmetrical in the depolarizing direction until the AC becomes a fraction of the DC component for the highest frequencies tested. Differences exist between the model and the experimental responses with regard to this low-pass filtering effect, but they almost certainly reflect differences in the response of individual cells (but see also Discussion). Figure 8 supports this conjecture by illustrating the AC/DC ratio as a function of frequency for the model compared to experimental responses for two cells that illustrate the range of possible experimental values (adapted from Figure 10 of Palmer and Russell 1986). The model response falls within the range of experimental values.

Fig. 8.

Ratio of the AC to the DC component of the IHC intracellular potential as a function of the stimulus frequency. Symbols illustrate the range of experimental values reported in Figure 10 of Palmer and Russell (1986). The line illustrates the response of the model.

Previous experimental (Kros and Crawford 1990; Kros 1996) and modeling studies (Zeddies and Siegel 2004) have suggested that the DC component of the receptor potential is not constant during the stimulus presentation, but is greatest at the beginning and then decreases toward a steady state. This adapting effect reflects the time course of activation of the basolateral K+ currents, mainly of the slow 4-AP-sensitive component (Zeddies and Siegel 2004), and is also reproduced by the present model (Fig. 3). The 5-ms rise ramp and the moderately low amplitude of the stimulus explain that it is only just visible in the waveforms of Figure 7. Careful inspection of Figure 7 shows a hint of a similar adaptation effect in the experimental responses (see, for instance, the 3000-Hz waveform).

Nonlinear input/output characteristics

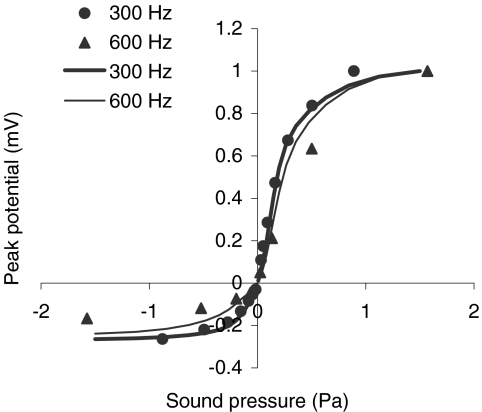

The receptor potential does not increase in proportion to the acoustic pressure over the range of tolerable SPLs. Instead, it increases compressively at high pressure levels (Dallos 1985b; Patuzzi and Sellick 1983). This behavior for low-frequency stimuli is illustrated by the transfer functions of Figure 9. Symbols illustrate experimental data for stimulus frequencies of 300 Hz (filled circle: data adapted from Fig. 1B of Russell and Sellick 1983) and 600 Hz (filled triangle: data adapted from Fig. 1A of Russell et al. 1986). Lines illustrate model responses for corresponding frequencies, as indicated by the figure inset. Transfer functions normalized with respect to the maximum receptor potential are shown rather than raw transfer functions to facilitate the comparison between model and experimental results while allowing for differences in the maximum conductance of the cells (the maximum values of the receptor potential were 13.4 and 14.6 for the experimental data at 300 and 600 Hz, respectively, and 30.6 and 29.9 for the model at corresponding frequencies). Clearly, the model accounts for the fact that the peak potential increases more in the depolarizing direction (relative to the resting membrane potential) than in the hyperpolarizing direction for positive/negative excursions of the sound pressure. In the model, as in the experimental data (Kros 1996), the peak potential saturates at very high SPLs as a result of the combined effect of the saturation of the transducer current (Fig. 2) and of the compression exerted by the basolateral K+ currents (Fig. 6). This issue is further discussed in the following section.

Fig. 9.

Normalized depolarizing and hyperpolarizing peak potentials in response to sinusoidal low-frequency stimuli. Symbols illustrate responses from basal IHCs: the 300-Hz data were adapted from Figure 1B of Russell and Sellick (1983), whereas the 600-Hz data were adapted from Figure 1A of Russell et al. (1986). Lines illustrate corresponding model responses. Normalized rather than raw values are plotted. These were calculated by dividing the peak receptor potential at any given pressure level by the maximum value of the receptor potential for all pressure levels. They therefore facilitate the comparison between model and experimental responses while allowing for differences in maximum cell conductance.

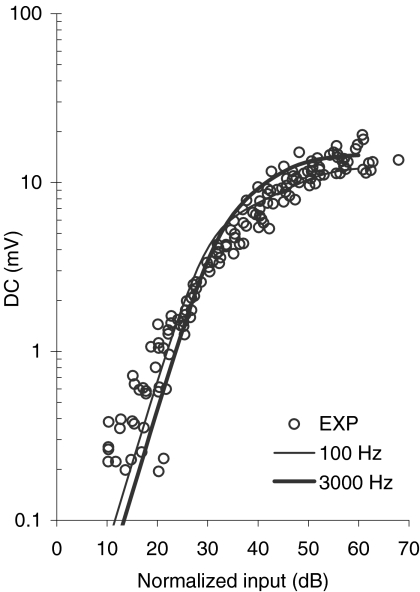

For high stimulation frequencies, the AC component is highly attenuated, and the receptor potential appears purely as a DC component (Fig. 7). This DC component increases with increasing the SPL at a rate greater than 1 dB/dB at low sound levels. As the sound level increases, the rate of increase of the DC component becomes smaller until it becomes less than 1 dB/dB, and thus compressive (Patuzzi and Sellick 1983). This experimental behavior is illustrated by the symbols of Figure 10. These data represent, quoting their authors, “the contribution of the IHC transduction mechanism to the DC receptor potential input–output curves at all frequencies,” i.e., the net IHC DC transfer function without any basilar-membrane nonlinear effects (Patuzzi and Sellick 1983, caption of Fig. 2). The lines of Figure 10 illustrate model responses for stimulation frequencies of 100 and 3000 Hz (as indicated by the inset) and for a range of stereocilia displacements from 1.25 to 1000 nm. (Note that the model normalized SPLs were calculated from the peak input stereocilia amplitude u using the following ad hoc expression: normalized SPL = −48 + 20 log10[u/(k × 20 × 10−6)], where k = 200 nm/Pa is the pressure-to-stereocilia displacement scaling factor.) The model accounts reasonably well for the nonlinear aspect of the response. For low normalized input levels, the model response has a slope of 2 dB/dB, which matches well with the observations (Dallos 1985a, p. 1596). The model shows a higher degree of compression at high SPLs than is observed in the data. Almost certainly, this is because model responses are affected by compression from two sources: one from the transducer and one related to the basolateral K+ currents, whereas the latter may be compromised in the data as a result of the electrode impalement.

Fig. 10.

Input–output functions for the DC receptor potential. Symbols illustrate experimental data for 12 basal IHCs in response to pure tones of low frequencies relative to the characteristic frequency of the cell (adapted from Figure 2 of Patuzzi and Sellick 1983). The experimental DC input–output curves were normalized by Patuzzi and Sellick so that all curves correspond at the 3-mV potential. This was performed to correct for any tuning of the basilar membrane. Lines illustrate model DC input–output responses for two stimulation frequencies, as indicated by the inset. Model DC amplitudes were not normalized. They were plotted directly as they result from evaluating the model for stereocilia displacements ranging from 1.25 to 1000 nm. The model normalized SPL values were calculated from the corresponding stereocilia displacements as explained in the text.

Model predictions

In vitro responses to the injection of half-wave rectified sinusoidal current bursts

Kros and Crawford (1990) demonstrated the compressive effect of basolateral K+ currents by passing constant-current pulses through the IHC membrane in vitro. They reasoned that, although these pulses do not exactly simulate steps of transducer current, their use provides some insight into the functioning of voltage-dependent basolateral K+ currents in vivo (Kros and Crawford 1990, p. 285). They, therefore, suggested that the observed compression must also affect the IHC potential in vivo (see also Kros 1996). In an in vivo situation, however, the time course of the inward transducer current approximates to a half-wave rectified sinusoid much more closely than to a step (cf. Fig. 1D of Kros et al. 1992). The resistance–capacitance properties of the membrane exert a low-pass filter effect on sinusoidal stimuli. Therefore, it is possible that the degree of compression be different for half-wave rectified sinusoidal-current bursts than for constant-current pulses, and that it depends on the frequency of the sinusoidal current. To investigate this possibility, the model was used to predict the results of an experiment similar to that of Kros and Crawford (1990) except that half-wave rectified sinusoidal-current bursts rather than constant-current pulses were passed through the membrane. This experiment should reveal the true contribution of basolateral K+ currents to the compressive input/output characteristics of the IHC, as it excludes any compressive effects from the transducer current.

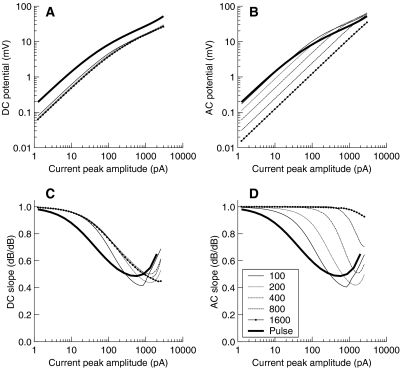

With the model, the membrane potential waveform was computed having half-wave rectified sinusoidal-current bursts of different amplitudes and frequencies injected at node V of Figure 1. The range of current amplitudes considered went from 1 to 2000 pA, which covers the range of transducer currents in vivo (Kros et al. 1992). The AC and DC components of the model's membrane potential were then calculated over the stabilized portion of the membrane potential waveform, typically over the last third of its duration (note that the AC component was calculated as the peak-to-peak component; see Fig. 7A). Figure 11A and B illustrates the results for a control cell (i.e., a cell with both gK,f and gK,s fully operative). The functions are plotted on a log–log scale because in this type of representation, any compressive behavior is easily identified with segments having a slope different from 1. Figure 11C and D illustrates the slopes (dB/dB) of the functions shown in Figure 11A and B, respectively.

Fig. 11.

Steady-state DC (A) and AC (B) potentials predicted by the model in response to injections of half-wave rectified sinusoidal current bursts of different amplitudes (abscissa) and frequencies (as indicated by inset in units of Hz). The thick continuous lines reproduce the model responses of Figure 6 (control cell) and illustrate the results when constant-current pulses are injected. Model responses were obtained using the in vitro configuration for a control cell, i.e., having both the fast and slow basolateral K+ conductances fully operative. gA was fixed to a value of 0.22 nS and CB to a value of 8 pF. (C, D) The slope (in dB/dB) of the functions in A and B, respectively.

Compressive responses occur for the DC component at all frequencies tested (Fig. 11A). As the amount of input current increases, the slope decreases from 1 dB/dB to a lowest value of around 0.5 dB/dB. This behavior is similar for all frequencies (Fig. 11C) and so is the lowest current amplitude above which compressive responses occur. Notably, the increase of the DC component is linear at low input-current amplitudes, whereas it was expansive (slope ∼2 dB/dB) in vivo (Fig. 10). Because Figure 11 shows the predicted contribution of the basolateral K+ currents to the input/output characteristics of the IHC, i.e., without the compressive effects of the transducer current, this suggests that the expansive DC responses observed in vivo almost certainly relate to the input/output characteristics of the transducer current.

The AC component also grows compressively with increasing the input current but only for low-frequency bursts. Figure 11B and C shows an apparent increase in the threshold current for compression with increasing the frequency of the sinusoidal burst. However, this change in threshold is only apparent as the threshold is always demonstrated at the same input current for the DC component (Fig. 11A). The compressive effect of basolateral K+ currents on the AC component decreases for high frequencies because of the shunting of the basolateral membrane impedance by the reactance of the membrane capacitance, which makes the activation of basolateral K+ currents less apparent.

The results for constant-current pulses already shown in Figure 6 (control cell) are plotted again in Figure 11 for comparison (thickest lines). The lowest slope for these is comparable with the lowest slopes of the AC and DC components for half-wave rectified sinusoids. Admittedly, for constant-current pulses, the model produces less compression than is observed experimentally (Fig. 6). Hence, in a real IHC, the actual degree of compression exerted by basolateral K+ currents is likely to be greater than is suggested by Figure 11C and D.

In summary, voltage-dependent basolateral K+ currents do compress the growth of the receptor potential, as suggested by Kros and Crawford (1990), and the degree of compression increases with increasing the amount of injected current up to at least 2-to-1 (slope of 0.5 dB/dB).

The contribution of voltage-dependent K+ currents to IHC compressive input/output functions in vivo

This section addresses the issue of to what extent the compression exerted on the intracellular potential by the voltage-dependent K+ currents adds to that caused by the transducer current in vivo. To do it, the growth of the cell potential with increasing the amplitude of stereocilia displacement was compared as computed with the in vivo configuration of the present IHC model (Fig. 1 and Table 1) and with another model that was in all identical except that its basolateral conductance was clamped to a constant value of 35 nS. This value for the conductance was arbitrarily chosen but is well within the range of observed values when the cell is hyperpolarized or highly depolarized (0.5–300 nS; reviewed by Dallos 1996, p. 25).

Figure 12A and B illustrates the DC and AC potentials (defined as in Fig. 7) for stimulation frequencies of 100 and 3000 Hz and for the two models considered. The dashed-dotted lines depict the results for the constant-conductance model, whereas the continuous lines illustrate the results for the model with voltage-dependent conductances. The dashed line illustrates a linear reference response. The values were calculated over the last third of the potential waveform obtained in response to sinusoidal bursts of stereocilia deflections of 60-ms duration. This minimizes the possibility that the values be influenced by the onset peaks that may occur as a result of hair-cell adaptation related to the activation of gK,s or gK,f (Fig. 3).

Fig. 12.

Comparison of steady-state nonlinear input–output functions as predicted by the in vivo IHC model proposed here, with time- and voltage-dependent basolateral K+ currents (continuous lines), and another model that was identical except that its basolateral K+ current was clamped to a constant value of 35 nS (dashed-dotted lines). Functions are illustrated for stimulus frequencies of 100 (thin lines) and 3000 Hz (thick lines). The dashed line illustrates linear reference responses with a slope of 1 dB/dB. (A) DC potential; (B) AC potential; (C, D) Slopes of the functions illustrated in A and B, respectively. The resting potential was −70.6 mV for the model with constant basolateral conductance and −60 mV for the model with the voltage-dependent conductance. Note the overlap between the AC responses (B and D) for the 3000-Hz tone with constant and varying basolateral K+ conductance.

Note that a detailed comparative discussion of the DC and AC potentials produced by the two models is not useful, as the results for the constant-conductance model will depend greatly on the value chosen for the conductance (in broad terms, the larger the conductance, the smaller the DC and the AC potentials). The results are illustrated in Figure 12A and B only because they help in understanding the rest of this discussion.

Much more informative is to compare the rate of growth of the cell potential with increasing stereocilia displacement, and this is shown in Figure 12C and D. Whereas for very large displacements (u > 200 nm) the rates of growth of the DC and AC potentials tend to become similar for the two models, for moderate displacements (5 nm < u < 200 nm), they are always smaller for the model with voltage-dependent basolateral conductances (continuous lines). This means that for moderate displacements, for which the transducer current is not yet saturated (Fig. 2), the compression exerted by the voltage-dependent conductances reduces the growth of the receptor potential. The maximum reduction factor [estimated as the ratio of slopes for the two models (not shown)] is at least 0.5, as was suggested in the previous section (Fig. 11).

Discussion

A new biophysical model of the IHC has been proposed that includes the nonlinear effects of the fast and slow voltage-dependent basolateral K+ currents (Kros and Crawford 1990). The proposed model is an approximation as it accounts for a subset of K+ currents only. The effects of other ionic currents (reviewed by Zeddies and Siegel 2004; Kros 1996), of negatively activating K+ currents (IK,n; Oliver et al. 2003; Marcotti et al. 2003), and of the ATP-activated currents (Sugasawa et al. 1996) are omitted. These approximations may explain the moderate deviations of the model from the experimental responses that occur in some cases. For example, the effects of ATP-activated currents and their variation along the cochlear position (Raybould et al. 2001) may be important to properly model the low-pass filtering function of the IHC, a characteristic that is still open to improvement for the current model (Fig. 7). Similarly, IK,n currents probably contribute to the resting conductance of IHCs and thereby to their membrane time constant and resting potential (Marcotti et al. 2003; Oliver et al. 2003). A complete model should also account for the small and slow calcium-dependent currents IK(Ca) described by Marcotti et al. (2004), although their function is uncertain at present. Developing an improved model that includes the effects of the omitted currents will be the subject of future efforts.

Despite the above-mentioned simplifications, the model reproduces in a reasonable manner a wide range of in vitro and in vivo experimental data pertaining to the input/output transfer characteristics of the IHC. It reproduces in vitro IHC transfer functions for conditions where the fast and slow basolateral K+ currents are selectively blocked (Figs. 3 and 6). It also reproduces in vivo observations of the growth of the DC and peak receptor potential as a function of sound level (or its corresponding stereocilia displacement; Figs. 9 and 10). Its main quantitative shortcoming is that its basolateral K+ currents contribute slightly less compression to the transfer characteristics of control cells than has been observed in vitro (Fig. 6). As discussed earlier, this may relate to the approximations made in the model.

That the model reproduces the nonlinear transfer characteristics of the IHCs in vivo is particularly important considering that the parameters were optimized based on in vitro data, and that their values remained the same throughout all evaluations. In other words, the in vivo transfer functions emerged naturally from modeling in vitro characteristics of the transducer and basolateral K+ currents without the need for further parameter adjustments. Of course, better fits to specific data sets would have been obtained by allowing the values of the present parameters to vary across evaluations, or by increasing the number of parameters as a result of incorporating the omitted membrane currents. Given the reasonable agreement between the model and experimental responses, the added complexity that these measures would introduce to the model is not justified for the purpose of the present work.

The model performance in vivo has always been compared with experimental data from basal regions of the guinea pig cochlea. There is evidence that the relative size of the fast and slow basolateral K+ currents as well as their reversal potentials are slightly different for apical and basal IHCs (Kimitsuki et al. 2003). These differences should be considered when applying the model to simulate the response of apical IHCs.

The model has been applied to investigate the relative contribution of the transducer and basolateral K+ currents to the nonlinear input/output transfer characteristics of the IHC. The model predicts that the basolateral K+ currents do not contribute to the observed expansive growth (slope of 2 dB/dB) of the DC receptor potential at low sound levels (compare Figs. 11C and 12C) and, hence, that such experimental result almost certainly reflects an expansive growth of the transducer conductance over a certain range of stereocilia displacements (Fig. 2).

The model also predicts that the basolateral K+ currents reduce the rate of growth of the DC receptor potential by at least a factor of 2 (when expressed in a log–log scale; Figs. 11 and 12) for stereocilia displacements above around 5 nm. It further predicts that their compressive effect on the DC potential is similar for all frequencies. The response of IHCs to pure tones generally reflects a combination of basilar membrane and IHC compression, but not when basal IHCs are considered and the frequency of stimulation is much lower than the CF of the cell. In such cases, the DC vs. sound level function represents the “true” transfer function of the IHC (Patuzzi and Sellick 1983). Careful analysis of IHC responses obtained in these conditions reveals that the DC receptor potential increases with sound level at a rate of approximately 0.5 dB/dB, consistent with the model prediction. For instance, Figure 1C of Patuzzi and Sellick (1983, case 1020) shows that for a cell with a CF of 18,000 Hz and a stimulation frequency of 0.39CF, the DC receptor potential increases compressively with level above approximately 80 dB SPL, with a slope of 0.5 dB/dB. Another example can be found in the report of Russell et al. (1986). Their Figure 6 illustrates that the DC receptor potential of an IHC with a CF of 16,000 Hz grows compressively with level for a stimulation frequency of 10,000 Hz with a slope of 0.53 dB/dB. Similarly, Figure 2 of Cheatham and Dallos (2001) shows a compressive growth of the average receptor potential for levels above 40 dB SPL for a CF of 4000 Hz and a stimulation frequency of 2000 Hz. Again, the slope is approximately 0.5 dB/dB. The close match between these results and the model predictions suggests that the observed compressive (slope of ∼0.5 dB/dB) growth of the DC receptor potential for sound levels for which the transducer current is not yet saturated may reflect the nonlinear, compressive effects of the basolateral K+ currents described by Kros and Crawford (1990).

The range of sound levels over which the compressive effects of basolateral K+ currents occur will generally depend on the displacement sensitivity of IHC stereocilia to sound pressure. This, in turn, varies depending on the CF of the cell and on the simulation frequency. For instance, a good match has been obtained here between experimental and model responses in vivo (Figs. 7, 8, and 9), assuming that the stereocilia-displacement sensitivity of basal cells to low-frequency stimuli is approximately 200 nm/Pa. This suggests that in these conditions (i.e., basal cells and low-frequency stimuli), the compressive effects will occur for sound levels above approximately 62 dB SPL (corresponding to a peak stereocilia displacement of 5 nm). This value will be lower, however, for stimulation frequencies near the cell's CF. Basal sites of the basilar membrane are around 40 dB more sensitive to stimuli at CF than to stimuli well below CF (e.g., Fig. 5 of Robles and Ruggero 2001). Assuming that stereocilia displacement relates to basilar membrane displacement similarly across stimulus frequencies, this means that for stimuli at CF, basolateral K+ currents almost certainly apply compression for sound levels above around 22 dB SPL. In other words, for stimuli near CF, K+-channel compression will affect sound levels near or just above the absolute threshold of hearing.

The compressive effect of the basolateral K+ currents affects the AC receptor potential in a similar way but, because of the low-pass filtering effect of the cell, only for low-frequency stimuli (Figs. 11 and 12).

Many composite models of the auditory periphery use crude algorithms to modeling the transfer characteristics of the IHC (reviewed by Lopez-Poveda 2005). Sometimes they are as simple as a nonlinear gain followed by a half-wave rectifier and a low-pass filter. In many cases, these models are used to explain perceptual data from physiological principles. Undoubtedly, the present model is computationally more expensive than those simple approaches. On the other hand, it provides precise control on some of the IHC physiological variables that may affect perception in normal and hearing-impaired listeners.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Spanish Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (grants PI02/0343 and G03/203), by the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (grant CIT-390000-2005-4), and by the European Regional Development Funds. We are indebted to Luis C. Barrio for suggesting us to produce the model, to Corné J. Kros for his comments on a poster version of this work, and to Ray Meddis, Fernán Jaramillo, and Ana Alves-Pinto for many useful discussions and for their critical reading of a draft of this paper. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions.

Appendix

This section provides a formal derivation of a general expression to compute the time evolution of the macroscopic fast and slow basolateral K+ currents for any time course of the membrane potential.

Kros and Crawford (1990) concluded that when a voltage step is applied to the IHC membrane, the time course of each of the two basolateral K+ currents, fast and slow, can be reasonably fitted by an equation of the form:

|

A1 |

where I0 is the value of the current before the voltage step is applied,  is the current at time infinity after the voltage step is applied, and τ1(VM) and τ2(VM) are two voltage-dependent time constants.

is the current at time infinity after the voltage step is applied, and τ1(VM) and τ2(VM) are two voltage-dependent time constants.

According to Kros and Crawford (1990), Eq. (A1) describes the behavior of a channel with two closed states (C1 and C2) and one open state (O) as follows (see also Dionne 1981):

|

A2 |

where α(VM), β(VM), γ(VM), and η(VM) denote the voltage-dependent rates at which the system evolves between states.

Macroscopically, C1, C2, and O may be interpreted as the proportion of channels in each state; hence, the three quantities add up to 1 [Eq. (A5)]. Therefore, the kinetics of such system can be described by the following system of three equations:

|

A3 |

|

A4 |

|

A5 |

where prime superscripts denote the first-order derivative with respect to time.

Solving Eq. (A3) for C2 [C2 = (O′ + γO)/β], Eq. (A5) for C1 (C1 = 1 −C2−O), substituting the solutions into Eq. (A4), and simplifying the resulting equation, we obtain:

|

A6 |

This is a linear, second-order differential equation that describes the time course of the proportion of open channels for any time course of VM, and hence the solution we were after.

Given the proportion of channels open at any given time and for any given membrane potential, O(t, VM), the channel conductance may then be calculated as:

|

A7 |

where Gmax is the maximum channel conductance, i.e., assuming that all the channels are in the open state.

Unfortunately, Eq. (A7) cannot be used directly to compute the conductance of each channel type because Kros and Crawford (1990) do not provide information about α(VM), β(VM), γ(VM), and η(VM). Instead, they provide detailed information on two time constants, τ1(VM) and τ2(VM). It is possible, however, to express Eq. (A6) in terms of the time constants instead of the rates. Our approach consists in finding a solution of Eq. (A6) for a voltage step, the condition considered by Kros and Crawford (1990), and compare it with Eq. (A1), the formula used by Kros and Crawford to fit their results.

Equation (A6) is a linear, nonhomogenous, second-order differential equation. Therefore, its solution (derived by applying formula 28.8, case 1, of Spiegel et al. 2000) has the form:

|

A8 |

where c1 and c2 are integration constants, and −M1 and −M2 are the roots of m2 + Am + B = 0, with A and B being the coefficients of O′ and O in Eq. (A6), respectively.

The actual values of c1 and c2 depend on boundary conditions, which are peculiar to each problem. When a voltage step is applied, O changes suddenly from an initial steady value (O0) to a final steady-state value  , and the following boundary conditions apply:

, and the following boundary conditions apply:

Boundary condition 1:

;

;Boundary condition 2: O(t = 0) = O0 ;

Boundary condition 3: O′(t = 0) = 0 ;

By applying boundary condition 1 to Eq. (A8), the following relationship results:

|

A9 |

Then, by applying boundary conditions 2 and 3 to Eq. (A8) and solving the resulting system of equations for c1 and c2, we obtain:

|

A10 |

|

A11 |

Substituting Eqs. (A9)–(A11) into Eq. (A8), the exact solution of O(t, VM) for a voltage step results as:

|

A12 |

Because Eq. (A12) is a solution of the general differential equation (A6) for the case considered by Kros and Crawford (1990), it must be equivalent in form to Eq. (A1).

Comparing the two equations, the following relationships between M1, M2, τ1, and τ2 emerge:

|

A13 |

|

A14 |

On the other hand, −M1 and −M2 are the roots of m2 + Am + B = 0, where A and B are the coefficients of O′ and O in Eq. (A6), respectively. Because m2 + Am + B = 0 may be rewritten in terms of its roots as m2 + (M1 + M2)m + M1M2 = 0, the following equivalences exist:

|

A15 |

|

A16 |

Therefore, Eq. (A6) may be rewritten as:

|

A17 |

From Eq. (A9), the term αβ in the above equation may be replaced by  to give:

to give:

|

A18 |

Finally, we can use Eqs. (A13) and (A14) to express the above differential equation in terms of the time constants, as we wanted:

|

A19 |

It is worth stressing that, in the above equation, the time constants τ1 and τ2 are voltage dependent, O depends both on time and voltage, and  depends on the voltage only. In other words,

depends on the voltage only. In other words,  denotes the proportion of channels opened assuming that the system achieves a steady-state instantly after a change in the membrane voltage, and hence, it may be calculated directly from the activation curve. The voltage dependence of the time constants and the activation curve are provided by Kros and Crawford (1990). Therefore, Eq. (A19) can be easily implemented digitally to calculate the proportion of channels open, and thus the conductance, at any given time and for any value of the membrane potential.

denotes the proportion of channels opened assuming that the system achieves a steady-state instantly after a change in the membrane voltage, and hence, it may be calculated directly from the activation curve. The voltage dependence of the time constants and the activation curve are provided by Kros and Crawford (1990). Therefore, Eq. (A19) can be easily implemented digitally to calculate the proportion of channels open, and thus the conductance, at any given time and for any value of the membrane potential.

Footnotes

Both authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- Bacon SP, Fay RR, Popper AN. Compression: From cochlear to cochlear implants. Springer-Verlag, New York, 2004.

- Cheatham MA, Dallos P. Inner hair cell response patterns: Implications for low-frequency hearing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110:2034–2044, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cooper NP. Compression in the peripheral auditory system. In: Bacon S, Fay RR, and Popper AN (eds) Compression: From cochlear to cochlear implants. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 19–61, 2004.

- Corey DP, Hudspeth AJ. Analysis of the microphonic potential of the bullfrog's sacculus. J. Neurosci. 3:942–961, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dallos P. Some electrical circuit properties of the organ of Corti. I. Analysis without reactive elements. Hear. Res. 12:89–119, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dallos P. Response characteristics of mammalian cochlear hair cells. J. Neurosci. 5:1591–1608, 1985a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dallos P. Membrane potential and response changes in mammalian cochlear hair cells during intracellular recording. J. Neurosci. 5: 1609–1615, 1985b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dallos P. Overview: cochlear neurobiology. In: Dallos P, Popper AN, and Fay RR (eds) The Cochlea. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 1–43, 1996.

- Dionne VE. The kinetics of slow muscle acetylcholine-operated channels in the garter snake. J. Physiol. 310:159–190, 1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gitter AH, Zenner HP. The cell potential of isolated inner hair cells in vitro. Hear. Res. 45:87–93, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kimitsuki T, Kawano K, Matsuda K, Haruta A, Nakajima T, Komune S. Potassium current properties in apical and basal inner hair cells from guinea-pig cochlea. Hear. Res. 180:85–90, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kros CJ. Hair cell physiology. In: Dallos P, Popper AN, and Fay RR (eds) The Cochlea. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 318–385, 1996.

- Kros CJ, Crawford AC. Potassium currents in inner hair cell isolated from the guinea-pig cochlea. J. Physiol. 421:263–291, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kros CJ, Rüsch A, Richardson GP. Mechano-electrical transducer currents in hair cells of the cultured neonatal mouse cochlea. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 249:185–193, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kros CJ, Lennan GWT, Richardson GP. Transducer current and bundle movement in outer hair cells of neonatal mice. In: Flock Å, Ottoson D, and Ulfendahl M (eds) Active Hearing. Elsevier Science, Oxford, pp 113–125, 1995.

- Lopez-Poveda EA. Spectral processing by the peripheral auditory system: Facts and Models. In: Malmierca MS and Irvine DR (eds) Auditory Spectral Processing. Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 7–48, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lukashkin AN, Russell IA. A descriptive model of the receptor potential nonlinearities generated by the hair cell mechanoelectrical transducer. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 103:973–980, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marcotti W, Johnson SL, Holley MC, Kros CJ. Developmental changes in the expression of potassium currents of embryonic, neonatal and mature mouse inner hair cells. J. Physiol. 548:383–400, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marcotti W, Johnson SL, Kros CJ. Effects of intracellular stores and extracellular Ca2+ on Ca2+-activated K+ currents in mature mouse inner hair cells. J. Physiol. 557:613–633, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mountain DC, Hubbard AE. Computational analysis of hair cell and auditory nerve processes. In: Hawkins HL, McMullen TA, Popper AN, and Fay RR (eds) Auditory Computation. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 121–156, 1996.

- Nuttall AL, Brown MC, Masta RI, Lawrence M. Inner hair cell responses to the velocity of basilar membrane motion in the guinea pig. Brain Res. 211:171–174, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oliver D, Knipper M, Derst C, Fakler B. Resting potential and submembrane calcium concentration of inner hair cell in the isolated mouse cochlea are set y KCNQ-type potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 23:2141–2149, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Palmer AR, Russell IJ. Phase-locking in the cochlear nerve of the guinea-pig and its relation to the receptor potential of inner hair-cell. Hear. Res. 24:1–15, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Patuzzi R, Sellick PM. A comparison between basilar membrane and inner hair cell receptor potential input–output functions in the guinea pig cochlea. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 74:1734–1741, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Raybould NP, Jagger DJ, Housley GD. Positional analysis of guinea pig inner hair cell membrane conductances: implications for regulation of the membrane filter. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2:362–376, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Robles L, Ruggero MA. Mechanics of the mammalian cochlea. Physiol. Rev. 81:1305–1352, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Russell IJ, Sellick PM. Low-frequency characteristics of intracellularly recorded receptor potentials in guinea-pig cochlear hair cells. J. Physiol. 338:179–206, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Russell IJ, Cody AR, Richardson GP. The responses of inner and outer hair cells in the basal turn of the guinea-pig cochlea and in the mouse cochlea grown in vitro. Hear. Res. 22:199–216, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shamma SA, Chadwich RS, Wilbur WJ, Morrish KA, Rinzel J. A biophysical model of cochlear processing: intensity dependence of pure tone responses. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 80:133–145, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spiegel MR, Liu J, Abellanas Rapún L. Fórmulas y tablas de matemática aplicada, 2nd ed. Madrid, McGraw-Hill Interamericana, 2000.

- Sugasawa M, Erostegui C, Blanchet C, Dulon D. ATP activates non-selective cation channels and calcium release in inner hair cells of the guinea-pig cochlea. J. Physiol. 491:707–718, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Van Emst MG, Giguère C, Smoorenburg GF. The generation of DC potentials in a computational model of the organ of Corti: effects of voltage-dependent K+ channels in the basolateral membrane of the inner hair cell. Hear. Res. 115:184–196, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zeddies DG, Siegel JH. A biophysical model of an inner hair cell. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116:426–441, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]