Abstract

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a member of the CCN family of proteins, is expressed by osteoblasts, but its function in cells of the osteoblastic lineage has not been established. We investigated the effects of CTGF overexpression by transducing murine ST-2 stromal cells with a retroviral vector, where CTGF is under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter. Overexpression of CTGF in ST-2 cells increased alkaline phosphatase activity, osteocalcin and alkaline phosphatase mRNA levels, and mineralized nodule formation. CTGF overexpression decreased the effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2 on Smad 1/5/8 phosphorylation and of Wnt 3 on cytosolic β-catenin, indicating that the stimulatory effect on osteoblastogenesis was unrelated to BMP and Wnt signaling. CTGF overexpression suppressed Notch signaling and induced the transcription of hairy and E (spl)-1 (HES)-1, by Notch-independent mechanisms. CTGF induced nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) transactivation by a calcineurin-dependent mechanism. Down-regulation of CTGF enhanced Notch signaling and decreased HES-1 transcription and NFAT transactivation. Similar effects were observed following forced CTGF overexpression, the addition of CTGF protein, or the transduction of ST-2 cells with a retroviral vector expressing HES-1. In conclusion, CTGF enhances osteoblastogenesis, possibly by inhibiting Notch signaling and inducing HES-1 transcription and NFAT transactivation.

Mesenchymal cells can differentiate into cells of various lineages, including osteoblasts, myoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes (1). The fate of mesenchymal cells and their differentiation toward cells of the osteoblastic lineage is tightly controlled by extracellular and intracellular signals. Some, such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs)2 and Wnt, favor osteoblastogenesis (2–4). Other signals, such as Notch, impair the differentiation of cells of the osteoblastic lineage (5).

Members of the CCN family of cysteine-rich (CR) secreted proteins include cysteine-rich 61 (Cyr 61), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov), and Wnt inducible secreted proteins (WISP) 1, 2, and 3 (6, 7). CCN proteins are highly conserved and share four distinct structural modules: an insulin-like growth factor-binding domain, a von Willebrand type C domain containing the CR domain, a thrombospondin-1 domain, and a C-terminal domain important for protein-protein interactions (6, 7). CCN proteins are structurally related to certain BMP antagonists, such as twisted gastrulation (Tsg) and chordin, and can have important interactions with regulators of osteoblast cell growth and differentiation (8).

CTGF is expressed in a variety of tissues, including bone and cartilage. In osteoblasts, CTGF expression is induced by BMP, transforming growth factor β (TGF β), Wnt, and cortisol, suggesting a possible role in the activity of these agents in bone (9–11). CTGF regulates different cellular functions, including adhesion, proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Targeted disruption of ctgf in mice leads to skeletal dysmorphisms, as a result of impaired cartilage/bone development and defective growth plate angiogenesis (12). The function of CTGF in skeletal cells is not well understood, and in vitro studies on the effects of CTGF in these cells have yielded controversial results. Experiments conducted in ctgf null calvarial osteoblasts or in C3H10T ½ cells following the down-regulation of CTGF using RNA interference (RNAi) have demonstrated that CTGF is necessary for osteoblastogenesis (10, 13). Transduction of C3H10T ½ cells with adenoviral vectors for the constitutive expression of CTGF results in impaired osteoblastogenesis (10). These observations suggest that CTGF is required for normal osteoblastic function, but its role under conditions of CTGF induction is less clear. Exposure of ctgf null osteoblastic cells to CTGF protein enhances osteoblastic function, whereas the addition of CTGF protein to cultures has been reported both to favor and oppose osteoblastic function in wild type cells (13–16).

By mechanisms that would resemble the activity of certain BMP or Wnt antagonists, CTGF binds to BMP-2 and -4 through its CR domain and binds to Wnt co-receptors through its C-terminal domain (16, 17). As a consequence, CTGF can modify BMP and Wnt signaling (16, 17). CTGF also interacts with TGF-β, enhancing its activity (16, 18). Recently, we demonstrated that the CCN protein Nov can bind BMP-2/4 and oppose BMP-2 and Wnt signaling and activity in cells of the osteoblastic lineage, mimicking the effects of more classic BMP antagonists (19). The structural similarities with BMP antagonists of the Tsg and chordin families and these observations indicate a potential functional relationship between CCN peptides and extracellular BMP antagonists (6).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the direct effects of CTGF on the differentiation and function of cells of the osteoblastic lineage. To this end, we transduced ST-2 stromal cell lines with a retroviral vector expressing CTGF under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. We determined the cellular phenotype and potential mechanisms responsible for the effects observed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Vectors and Packaging Cell Lines—A 1046-bp DNA fragment containing the murine ctgf coding sequence (R. P. Ryseck, Princeton, NJ), with a FLAG epitope tag on the C-terminal end (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA), or a 1.4-kb DNA fragment containing the hairy and E (spl)-1 (hes-1) coding sequence (ATCC) with a FLAG epitope tag on the N-terminal end were cloned into pcDNA 3.1 (Invitrogen) for use in acute transfection experiments or cloned into the retroviral vector pLPCX (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) for the creation of transduced cell lines. In both vectors, a CMV promoter directs the constitutive expression of the gene of interest. The vectors pLPCX, pLPCX-CTGF, and pLPCX-HES-1 were transfected into Phoenix packaging cells (ATCC) by calcium phosphate/DNA co-precipitation and glycerol shock, and cells were selected for puromycin resistance, as described (20). Retrovirus-containing conditioned medium was harvested, filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane, and used to transduce ST-2 cells.

Cell Culture—ST-2 cells, cloned stromal cells isolated from bone marrow of BC8 mice, were grown in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C in α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM, Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA) (21, 22). For the creation of cell lines, ST-2 cells were transduced with pLPCX vector or with pLPCX-CTGF or pLPCX-HES-1 by replacing the culture medium with retroviral conditioned medium from Phoenix packaging cells in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by incubation for 16–18 h at 37 °C (20). The culture medium was replaced with fresh α-MEM medium, and cells were grown, trypsinized, replated, and selected for puromycin resistance. Transduced cells were plated at a density of 104 cells/cm2, and cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum until reaching confluence (2–4 days). At confluence ST-2 cells were transferred to α-MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and 5 mm β-glycerophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured for an additional 1–4 weeks, as indicated in the text and legends. To study effects on signaling mothers against decapentaplegic (Smad) phosphorylation, confluent cells were serum-deprived overnight and treated with BMP-2 (Wyeth Research, Collegeville, PA) for 20 min. To study effects on β-catenin levels, confluent cells were serum-deprived overnight and treated with Wnt 3a (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 6 h. To examine for changes in reporter activity, subconfluent wild-type ST-2 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors as described under transient transfections. To down-regulate CTGF or HES-1 expression, subconfluent wild-type ST-2 cells were transfected with small interfering (si)RNAs as described under RNA interference (RNAi). In selected experiments, wild-type ST-2 cells were cultured under the same conditions, and recombinant human CTGF (rhCTGF) protein (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was added, as indicated in the text and legends.

Real-time Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)—Total RNA was extracted, and CTGF, alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, regulators of calcineurin (rcan)1 exon 4, and HES-1 mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR (23, 24). For this purpose, 1–10 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using a SuperScript III Platinum Two-Step qRT-PCR kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions and amplified in the presence of 5′-CACTCCGGGAAATGCTGCAAGGAG-[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-GTTGGGTCTGGGCCAAATGT-3′ primers for CTGF; 5′-CGGTTAGGGCGTCTCCACAGTAAC-[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-CTTGGAGAGGGCCACAAAGG-3′ primers for alkaline phosphatase; 5′-CACTTACGGCGCTACCTTGGGTAAGT[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-CCCAGCACAACTCCTCCCTA-3′ primers for osteocalcin; 5′-GACTTTCACGGCCTCTGAGCACAGAAAG[FAM]C-3′ and 5′-ATTCTTGCCCTTCGCCTCTT-3′ primers for HES-1; 5′-CAAGCGCAAAGGAACCTCCAGC[FAM]TG-3′ and 5′-GGCAGACGCTTAACGAACGA-3′ for rcan1 exon 4; 5′-CACGCTCTGGAAAGCTGTGGCG[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-AGCTTCCCGTTCAGCTCTGG-3′ primers for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH); and 5′-CGAACCGGATAATGTGAAGTTCAAGGTT[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-CTGCTTCAGCTTCTCTGCCTTT-3′ primers for ribosomal protein L38 (RPL38). The PCR reaction was carried out in the presence of Platinum Quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen) at 54–60 °C for 45 cycles. Gene copy number was estimated by comparison with a standard curve constructed using CTGF (R. P. Ryseck) and alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and HES-1 (all three from ATCC) DNAs and corrected for GAPDH (R. Wu, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) or for RPL38 (ATCC) copy number (25, 26). Reactions were conducted in a 96-well spectrofluorometric thermal iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and fluorescence was monitored during every PCR cycle at the annealing step.

Cytochemical Assays and Alkaline Phosphatase Activity—To determine mineralized nodule formation, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and stained with 2% alizarin red (Sigma-Aldrich) (27). APA was determined in 0.5% Triton X-100 cell extracts by the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate to p-nitrophenol and measured by spectroscopy at 405 nm after 10 min of incubation at room temperature according to manufacturer's instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). Data are expressed as nanomoles of p-nitrophenol released per minute per microgram of protein. Total protein content was determined in cell extracts by the DC protein assay, in accordance with manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad).

Western Immunoblot Analysis—To detect CTGF-FLAG peptide, culture medium from ST-2 cells transduced with pLPCX or pLPCX-CTGF was precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. To detect HES-1 FLAG peptide, lysates were extracted from cells transduced with pLPCX or pLPCX-HES-1. Medium and cell lysates were cleared with M2 affinity beads (Sigma-Aldrich), and the bound protein was eluted by adding FLAG peptide in excess. Proteins were fractionated by gel electrophoresis in 12% polyacrylamide gels under non-reducing conditions (28) and transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and exposed overnight to 2 μg/ml of mouse monoclonal antibody FLAG-M2 raised against FLAG fusion proteins (Sigma-Aldrich). CTGF-FLAG was identified by migration at the expected molecular mass of ∼38 kDa (6, 11). HES-1-FLAG was identified by migration at the expected molecular mass of ∼32 kDa (29, 30). To determine the level of Smad 1/5/8 phosphorylation, the cell layer of ST-2 cells transduced with pLPCX, pLPCX-CTGF, or pLPCX-HES-1 was washed with cold PBS and extracted in cell lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mm EDTA) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitors, as described (31, 32). Protein concentration was determined by the DC protein assay, and 20 μg of total cellular protein was fractionated by electrophoresis in 12.5% polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions and transferred to Immobilon P membranes. The membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS and exposed to a rabbit polyclonal antibody, which recognizes Smads 1, 5, and 8 phosphorylated at Ser-463/465 (Smad 1 and 5), and Ser-426/428 (Smad 8) (Cell Signaling Technology), or exposed to a rabbit polyclonal antibody to unphosphorylated Smad 1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) (33, 34). To determine β-catenin levels, the cell layer was extracted in 10 mm Tris, 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, and 2 mm dithiothreitol buffer at pH 7.6, in the presence of protease inhibitors, and the cytosolic fraction was separated by ultracentrifugation, as described (35). 20 μg of protein was fractionated by electrophoresis in 7.5% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon P membranes. The membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS and exposed to a monoclonal antibody to unphosphorylated β-catenin or a polyclonal antibody to human actin (both, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were exposed to anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antiserum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and developed with a chemiluminescence detection reagent (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Transient Transfections—To determine changes in BMP-2 signaling, a construct containing 12 copies of a Smad 1/5 consensus sequence linked to an osteocalcin minimal promoter and a luciferase reporter gene (12xSBE-Oc-pGL3, M. Zhao, San Antonio, TX) was tested in transient transfection experiments (36). To determine changes in Wnt/β-catenin transactivating activity, a construct containing 16 copies of the lymphoid enhancer binding factor/T-cell-specific factor (Lef1/Tcf-4) recognition sequence, cloned upstream of a minimal thymidine kinase promoter and a luciferase reporter gene (16xTCF-Luc, J. Billiard, Wyeth Research) was tested in transient transfection experiments (37). To determine changes in Notch 1 signaling, a construct containing six multimerized dimeric CBF1/Suppressor of Hairless/Lag 1 (CSL) binding sites, linked to the β-globin basal promoter (12xCSL-Luc, L. J. Strobl, Munich, Germany), or a 354-bp fragment of the HES-1 promoter (U. Lendahl, Stockholm, Sweden), both cloned upstream of a luciferase reporter gene, were tested (38–41). To determine changes in nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) signaling, a construct containing nine copies of an NFAT response element, linked to a minimal α-myosin heavy chain promoter and cloned into pGL3 basic (9xNFAT-Luc, J. D. Molkentin, Cincinnati, OH) was tested (42). To test effects of CTGF, wild-type ST-2 cells were cultured to 70% confluence and transiently transfected with pcDNA-CTGF expression vector or pcDNA 3.1, and with the indicated constructs using FuGENE6 (3 μl of FuGENE/2 μg of DNA), according to manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science). Alternatively, wild-type ST-2 cells were cultured to subconfluency, transfected with selected reporter constructs, serum deprived for 6 h, treated with rhCTGF, and harvested after 24 h. To test for effects of HES-1, wild-type ST-2 cells were cultured to subconfluency and transiently transfected with pcDNA 3.1, or pcDNA-HES-1 in the absence or presence of pcDNA-HES related protein (HERP)-2 (T. Iso, Los Angeles, CA) expression constructs and with the 9xNFAT-Luc reporter construct, as described for CTGF (29). A CMV-directed β-galactosidase expression construct (Clontech) was used to control for transfection efficiency. In experiments testing for effects of Notch signaling on 12xCSL-Luc reporter or HES-1 promoter, cells were co-transfected with a Notch intracellular domain (NICD) expression construct cloned into pcDNA 3.1 (pcDNA-NICD) or with control vector (5). For 16xTCF-Luc activity, cells were co-transfected with a Wnt 3 expression construct cloned into pUSEamp (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) or control vector. Cells were exposed to the FuGENE-DNA mix for 16 h, transferred to serum containing test or control medium for 24 h, and harvested. For 12xSBE-Oc-pGL3 activity, cells were exposed to the FuGENE-DNA mix for 16 h and transferred to serum-free medium for 8 h, treated with or without BMP-2 for 24 h, and harvested. In selected experiments testing for 12xCSL-Luc, HES-1 promoter or 9xNFAT-Luc reporter activity, cells were treated either with the 26 S proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich), a γ-secretase II inhibitor (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), or the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA), as indicated in the text and legends. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured using an Optocomp luminometer (MGM Instruments, Hamden, CT). Luciferase activity was corrected for β-galactosidase activity.

RNA Interference—To down-regulate CTGF and HES-1 expression, double-stranded (si)RNAs were obtained commercially (CTGF, 21 bp, Ambion, Austin, TX; HES-1, 20 bp, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). A scrambled 19-bp siRNA with no homology to known mouse or rat sequences was used as a control (Ambion) (43, 44). CTGF, HES-1, or scrambled siRNA at 20–40 nm were transfected into 60% confluent ST-2 cells, using siLentFect lipid reagent, in accordance with manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad), and allowed to recover for 18 h. To test for the effect of CTGF down-regulation on Notch signaling, cells were co-transfected with pcDNA 3.1 or pcDNA-NICD expression vectors and 12xCSL-Luc reporter or HES-1 promoter constructs. To test for the effect of CTGF down-regulation on NFAT transactivation, cells were transfected with 9xNFAT-Luc reporter. To test for the effect of HES-1 down-regulation on CTGF-induced NFAT transactivation, cells were co-transfected with pcDNA-CTGF or pcDNA 3.1 expression vectors and with 9xNFAT-Luc reporter. To ensure adequate down-regulation, total RNA was extracted in parallel cultures, and CTGF and HES-1 mRNA levels determined by real-time RT-PCR.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay—For gel shift assays, nuclear extracts from ST-2 cells transduced with pLPCX or pLPCX-HES-1 and treated with BMP-2 were prepared as described (31, 45). Synthetic oligonucleotides containing a consensus herp-2 binding sequence (5′-TCGAGGGTGGCAGGTGCCATT-3′) that binds HERP-2 preferentially over HES-1, and its mutant (5′-TCGAGGGTGGCTTTTGCCATT-3′), in which the mutated bases are underlined, were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (29). Synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotides were labeled with [γ-32]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Nuclear extracts and labeled oligonucleotides were incubated for 20 min at room temperature in 10 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.5) containing 3 μg of poly(dI-dC). The specificity of binding was determined by the addition of homologous or mutated unlabeled synthetic oligonucleotides in 100-fold excess. DNA-protein complexes were resolved on non-denaturing, non-reducing 4% polyacrylamide gels, and the complexes were visualized by autoradiography.

Statistical Analysis—Data are expressed as means ± S.E. Statistical differences were determined by Student's t test or analysis of variance.

RESULTS

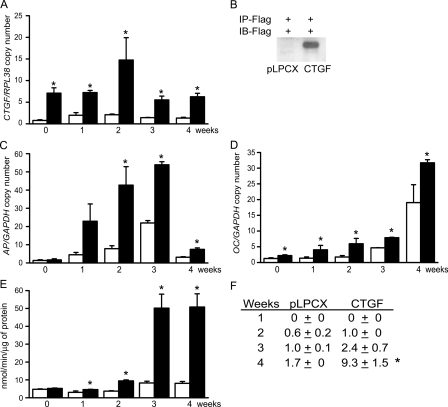

To examine the impact of CTGF on the ST-2 cell phenotype, ST-2 cells were transduced with the retroviral expression construct pLPCX-CTGF and compared with cells transduced with pLPCX vector. CTGF overexpression was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR, and by Western immunoblot analysis, which confirmed the overexpression of a ∼38-kDa protein, the predicted molecular mass of CTGF (6, 11) (Fig. 1). CTGF mRNA levels remained relatively constant in wild-type pLPCX cells, and they were significantly increased in pLPCX-CTGF-transduced cells over a 4-week culture period. Cells overexpressing CTGF were cultured under osteoblastic differentiating conditions for up to 4 weeks. CTGF overexpression increased osteocalcin and alkaline phosphatase transcripts when compared with vector-transduced cells (Fig. 1). In addition, CTGF overexpression increased alkaline phosphatase activity and the formation of mineralized nodules, indicating that, in vitro, CTGF favored osteoblastic cell maturation (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of CTGF overexpression on the differentiation of ST-2 stromal cells. ST-2 cells transduced with pLPCX or pLPCX-CTGF were cultured to confluence (0) or for up to 4 weeks following confluence. In A, C, and D, total RNA was extracted from pLPCX (white bars) and pLPCX-CTGF (black bars) cells cultured for 4 weeks (A, C, D, and E), and subjected to real-time RT-PCR for the determination of CTGF (A), alkaline phosphatase (C), and osteocalcin (D) and GAPDH or RPL38 mRNA. Data are expressed as ctgf, alkaline phosphatase (AP) or osteocalcin (OC) copy number corrected for gapdh or rpl38 expression. In B, conditioned medium was obtained from cells cultured for 24 h in the absence of serum following confluence. Affinity immunopurified (IP) proteins were resolved by gel electrophoresis, transferred to an Immobilon P membrane, exposed to an antibody to the FLAG tag for the immunoblot (IB) and visualized by chemiluminescence. In E, alkaline phosphatase activity (APA) was quantified in total cell extracts from pLPCX (white bars) or from pLPCX-CTGF (black bars) cells cultured for 4 weeks. APA is expressed as nanomoles or p-nitrophenol/min/μg of total protein. In F, the table indicates the number of mineralized nodules in pLPCX or pLPCX-CTGF cells cultured in the presence of BMP-2 at 1 nm. Bars and data for all panels represent means ± S.E. for 3 (C and D), 4 (A), and 6 (E and F) observations. *, significantly different between pLPCX and pLPCX-CTGF cells, p < 0.05.

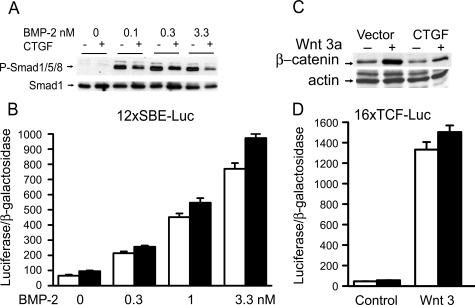

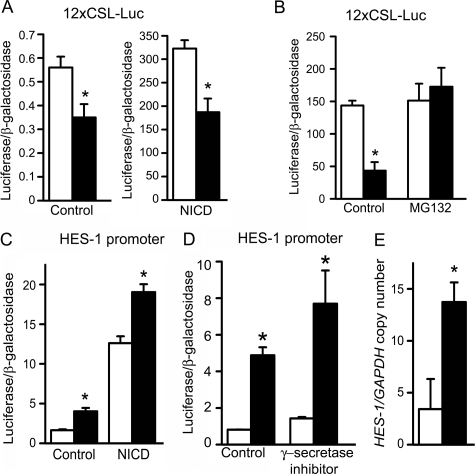

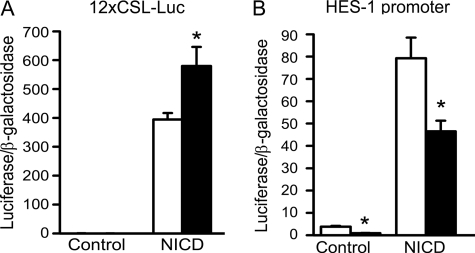

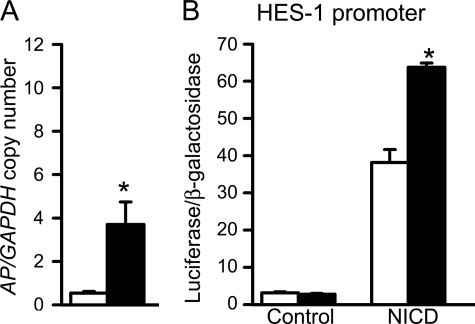

To elucidate the mechanism of the CTGF effects on osteoblastic differentiation, we analyzed the impact of CTGF overexpression on downstream events of BMP-2 and Wnt 3 signaling, because both proteins were reported to interact with CTGF and to affect osteoblastogenesis (10, 16, 17). The signaling pathway used by BMPs is cell line-dependent, and previously we have shown that in ST-2 cells BMP-2 activates the Smad signaling pathway (36). CTGF did not have a consistent effect on the transactivation of the BMP/Smad 1/5-dependent 12xSBE-Oc-pGL3 reporter construct, and in accordance with previously reported BMP antagonizing actions, CTGF caused a modest inhibition of Smad 1/5/8 phosphorylation (Fig. 2) (16). CTGF overexpression did not modify the basal activity or the stimulatory effect of Wnt 3 on the Wnt-dependent 16xTCF-Luc construct, and CTGF decreased the level of cytosolic β-catenin in control and Wnt 3a-treated cells (Fig. 2). These observations indicate that CTGF does not enhance, and tends to oppose the effects of BMP and Wnt on signaling. Consequently, the stimulation of osteoblastogenesis caused by CTGF in vitro is independent from BMP-2/Smad or Wnt/β-catenin signaling. To explore alternative mechanisms involved in the stimulatory effects of CTGF on osteoblastogenesis, CTGF/Notch interactions were examined. Notch inhibits osteoblastogenesis, and its activity is down-regulated by another CCN protein, Nov (19). An NICD expression vector transfected into ST-2 cells induced the transactivation of the Notch-dependent 12xCSL-Luc reporter construct, containing six multimerized dimeric CSL binding sequences, and induced the activity of a promoter fragment of HES-1, a Notch target gene (Fig. 3). CTGF overexpression caused a decrease in the transactivation of the 12xCSL-Luc reporter under basal conditions and in the presence of NICD (Fig. 3). Treatment of ST-2 cells with MG132, a specific inhibitor of the 26 S proteasome, did not alter the effect of NICD on 12xCSL-Luc transactivation, but reversed the inhibitory effect of CTGF on Notch signaling. This indicates that CTGF inhibits the canonical Notch signaling pathway, possibly by promoting the proteasome degradation of the NICD protein. Despite the inhibitory effect of CTGF on the Notch reporter construct, CTGF overexpression induced the activity of the HES-1 promoter, and increased HES-1 mRNA levels (Fig. 3). The inhibition of γ-secretase II, which precludes one of the three cleavages required for the release of the NICD and its translocation to the nucleus, did not change the activity of the HES-1 promoter induced by CTGF. These results indicate that CTGF decreases Notch signaling in ST-2 cells, and that the induction of HES-1 transcription by CTGF is not mediated by the canonical Notch signaling pathway. To ensure the validity of the results observed in ST-2 cells overexpressing CTGF, down-regulation of CTGF expression by RNAi and addition of exogenous rhCTGF protein were tested in ST-2 stromal cells. Down-regulation of CTGF expression caused the converse effect of the one observed in cells overexpressing CTGF, and enhanced the effect of NICD on 12xCSL-Luc reporter transactivation (Fig. 4). In addition, basal and NICD-induced HES-1 transcriptions were decreased in the context of CTGF down-regulation (Fig. 4). In accordance with the results described in transduced cells, the addition of rhCTGF increased the expression of alkaline phosphatase mRNA levels and the activity of the HES-1 promoter construct (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of CTGF overexpression on BMP/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in ST-2 stromal cells. For Smad 1/5/8 phosphorylation (A) and β-catenin levels (C), ST-2 cells transduced with pLPCX vector (-) or pLPCX-CTGF (+) were cultured to confluence, serum-deprived overnight and treated with either BMP-2 at 0.1–3.3 nm for 20 min or Wnt 3a at 2.7 nm for 6 h. Total cell lysates (A) or cytosolic extracts (C) were resolved by gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon P membranes, which were incubated either with antibodies to phosphorylated Smad 1/5/8 and to unphosphorylated Smad 1, or with antibodies to β-catenin and actin. For 12xSBE-Oc-pGL3 transactivation (B), subconfluent ST-2 cells were transiently transfected with control pcDNA 3.1 (white bars) or pcDNA-CTGF (black bars) expression vectors, and with 12xSBE-Oc-pGL3 and a CMV/β-galactosidase reporter construct. After 16 h, cells were switched to serum-free medium for 8 h and treated with BMP-2 at 0.3–3.3 nm for 24 h. For 16xTCF-Luc transactivation (D), subconfluent ST-2 cells were transiently transfected with control pcDNA 3.1 (white bars) or pcDNA-CTGF (black bars) expression vectors concomitantly with 16xTCF-Luc reporter construct, with and without a Wnt 3 expression construct, and a CMV/β-galactosidase reporter construct, and harvested after 48 h. Data shown represent luciferase/β-galactosidase activity for control pcDNA 3.1 and pcDNA-CTGF transfected cells. Bars represent means ± S.E. for six observations.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of CTGF overexpression on Notch signaling in ST-2 stromal cells. In A–D, subconfluent ST-2 cells were transiently transfected with control pcDNA (white bars), or pcDNA-CTGF (black bars) expression vector, and with a Notch-dependent 12xCSL-Luc reporter (A and B) or a HES-1 promoter construct (C and D) and a CMV/β-galactosidase expression vector, and with a Notch intracellular domain (NICD) or control expression constructs (A and C) and harvested after 48 h. In B, cells were treated or not with MG132 at 0.5 μm 1 h prior to the co-transfection with 12xCSL-Luc reporter and NICD expression constructs. In D, cells were treated or not with γ-secretase II inhibitor 1 h prior to the transfection with the HES-1 promoter construct. Data shown represent luciferase/β-galactosidase activity for control and CTGF-transfected cells. In E, total RNA from confluent pLPCX (white bars)- or pLPCX-CTGF (black bars)-transduced cultures was reverse transcribed and amplified by real-time RT-PCR in the presence of specific primers to detect hes-1. Data are expressed as hes-1 copy number corrected for gapdh expression. Bars represent means ± S.E. for 3 (E) or 6 (A–D) observations. *, significantly different between cells overexpressing CTGF and control cells, p < 0.05.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of CTGF down-regulation on Notch signaling in ST-2 cells. ST-2 cells were transfected with CTGF (black bars) or scrambled (white bars) small interfering (si)RNA and with a Notch intracellular domain (NICD) or control expression constructs, and with a 12xCSL-Luc reporter (A) or a HES-1 promoter construct (B) and a CMV/β-galactosidase expression vector, and harvested after 48 h. Bars represent means ± S.E. for 6 observations. The ctgf copy number corrected for rpl38 was (means ± S.E.; n = 4) 2.9 ± 0.7 in control and 1.6 ± 0.2 in cells transfected with CTGF siRNA (p < 0.05). *, significantly different between control and CTGF down regulated cells, p < 0.05.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of added CTGF protein on alkaline phosphatase mRNA levels and HES-1 promoter activity in ST-2 stromal cells. In A, ST-2 cells were cultured to confluence and treated (black bars) or not (white bars) with rhCTGF at 300 ng/ml for 24 h. Total RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified by real-time RT-PCR in the presence of specific primers to detect alkaline phosphatase (AP) and GAPDH mRNA. Data are expressed as alkaline phosphatase copy number corrected for gapdh expression. In B, subconfluent ST-2 cells were transiently transfected with a HES-1 promoter construct, with a Notch intracellular domain (NICD) or a control expression construct and a CMV/β-galactosidase expression vector. After 16 h, cells were switched to serum-free α-MEM for 6 h and treated (black bars) or not (white bars) with rhCTGF at 300 ng/ml for 24 h and harvested. Data shown represent luciferase/β-galactosidase activity. Bars represent means ± S.E. for three (A) or six observations (B). *, significantly different between CTGF treated and control cells, p < 0.05.

To determine whether HES-1 mediated effects of CTGF on ST-2 cells, down-regulation of HES-1 by RNAi was considered. However, our previous work using RNAi demonstrated that basal expression of HES-1 has an inhibitory effect on selected parameters of osteoblastogenesis (5). In addition, down-regulation of HES-1 using RNAi could be used to test only short term effects of CTGF, because HES-1 mRNA suppression lasts for periods of up to 96 h following siRNA transfection. Because of these reasons and the fact that most of the actions of CTGF in vitro occurred following its overexpression for periods of ≥1 week, we explored whether long term forced overexpression of HES-1 mimicked the effects of CTGF. For this purpose, ST-2 cells were transduced with the retroviral pLPCX-HES-1 vector. Overexpression of HES-1 was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR, and by Western immunoblot analysis, which revealed the expression of a 32-kDa protein (Fig. 6) (29, 30). Cells overexpressing HES-1 were cultured under osteoblastic differentiating conditions for up to 4 weeks, and during this period HES-1 overexpression was sustained in pLPCX-HES-1 cells. HES-1 stimulated alkaline phosphatase activity over a 4-week culture period (Fig. 6). To elucidate the mechanism of HES-1 action in ST-2 cells, we analyzed its effect on BMP-2 and Wnt signaling. HES-1 overexpression did not alter the effect of BMP-2 on Smad 1/5/8 phosphorylation or on the transactivation of the Smad 1/5-dependent 12xSBE-Oc-pGL3 reporter construct (not shown). In addition, HES-1 did not modify the effect of Wnt 3a on levels of cytoplasmic β-catenin or on the transactivation of the Wnt dependent 16xTCF-Luc reporter construct (not shown). These results indicate that HES-1, like CTGF, does not enhance BMP/Smad or Wnt/β-catenin signaling. To explore additional mechanisms involved, we tested whether HES-1 induced NFAT transactivation, because in non-skeletal cells NFAT can be regulated by HES-1 and NFAT induces osteoblastogenesis (46–48). Forced overexpression of HES-1 enhanced the transactivation of an NFAT reporter construct, where nine repeats of NFAT consensus sequences direct luciferase expression, by a calcineurin-dependent mechanism. To study the mechanisms involved in the induction of NFAT by HES-1, we examined for potential interactions between HES-1 and the related HERP-2, which is known to form heterodimers with HES-1 and to inhibit osteoblastogenesis (29, 49). HERP-2 decreased the transactivation of the transfected 9xNFAT-Luc reporter and opposed the effect of HES-1 (Fig. 6). Interactions of HES-1 with HERP-2 were analyzed by EMSA. Control and HES-1-overexpressing cells were cultured to confluence and treated with BMP-2 to enhance HERP-2 expression (49). Nuclear extracts bound to herp-2 consensus oligonucleotides, designed to recognize HERP-2 preferentially over HES-1, and the complex was displaced by unlabeled homologous, but not by mutated, oligonucleotides in excess (29). Nuclear extracts from HES-1-overexpressing cells exhibited a modest decrease in binding of nuclear proteins to the herp-2 consensus sequence, suggesting that the overexpressed HES-1 interacts to some extent with HERP-2 decreasing, but not preventing, its binding to the consensus herp-2 site (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of HES-1 overexpression on alkaline phosphatase activity (APA) and NFAT transactivation in ST-2 stromal cells. In A, B, C, D, and G, ST-2 cells transduced with pLPCX or pLPCX-HES-1 were cultured for up to 4 weeks following confluence. In E and F, wild-type ST-2 cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 or pcDNA-HES-1. In A and B, total RNA was extracted from pLPCX (white bars) and pLPCX-HES-1 (black bars) cells cultured to confluence (A) or for 4 weeks (B) and subjected to real-time RT-PCR for the determination of HES-1 and GAPDH mRNA. Data are expressed as hes-1 copy number corrected for gapdh expression. In C, affinity immunopurified (IP) cell extracts were resolved by gel electrophoresis, transferred to an Immobilon P membrane, exposed to an antibody to the FLAG tag for the immunoblot (IB), and visualized by chemiluminescence. In D, APA was quantified in total cell extracts from pLPCX (white bars) or from pLPCX-HES-1 (black bars) transduced cells cultured for 1–4 weeks after confluence. APA is expressed as nanomoles of p-nitrophenol/min/μg of total protein. In E, wild-type ST-2 cells were cultured to subconfluency and transiently transfected with pcDNA (white bars) or pcDNA-HES-1 (black bars), and with 9xNFAT-Luc and a CMV/β-galactosidase expression vector in the presence of vehicle or the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 at 10–100 μg/ml for 24 h. Data shown represent luciferase activity/β-galactosidase activity. In F, ST-2 cells were cultured to subconfluency and transiently transfected with pcDNA (white bars), pcDNA-HES-1 (black bars), pcDNA-HERP-2 (gray bars) or both, pcDNA-HES-1 and pcDNA-HERP-2 (horizontal lined bars), expression vectors, and with 9xNFAT-Luc and a CMV/β-galactosidase reporter construct and harvested after 48 h. Data shown represent luciferase activity/β-galactosidase activity. In G, EMSA demonstrating DNA-protein complexes resolved by gel electrophoresis in 4% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography. Nuclear extracts from ST-2 cells transduced with pLPCX or pLPCX-HES-1 cultured to confluence and treated with BMP-2 at 3.3 nm were incubated with a [γ-32]ATP-labeled 20-bp oligonucleotide containing a herp-2 consensus sequence. EMSAs were performed in the presence and absence of unlabeled herp-2 cognate and mutated sequences in excess. Bars represent means ± S.E. for three (A and B) or six (D–F) observations. *, significantly different between control and HES-1-expressing cells, p < 0.05. +, significantly different between control and FK506, p < 0.05.

CTGF, like HES-1, induced NFAT signaling. Forced CTGF expression or the addition of rhCTGF was tested for their effects on the activity of the NFAT reporter construct. Forced overexpression of CTGF caused a calcineurin-dependent induction of NFAT transactivation (Fig. 7) and increased the expression of the NFAT target gene rcan1 exon 4 by 2-fold (p < 0.05, not shown). The stimulatory effect on transactivation also was observed with added CTGF protein, and in accordance with these results, down-regulation of CTGF expression by RNAi decreased the transactivation of the transfected 9xNFAT-Luc reporter. HES-1 down-regulation decreased, but did not preclude the effect of CTGF on the transactivation of the 9xNFAT-Luc reporter (Fig. 7). This suggests that HES-1 is only partially necessary for this effect of CTGF and that CTGF can activate NFAT by HES-1-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of CTGF on NFAT transactivation in the context of calcineurin inhibition or of HES-1 down-regulation in ST-2 stromal cells. In A, ST-2 cells were cultured to subconfluency and transiently transfected with control pcDNA (white bars) or pcDNA-CTGF (black bars), and with 9xNFAT-Luc and CMV/β-galactosidase expression vectors. Cells were treated with vehicle or the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 at the indicated doses, 1 h prior to the transfection. In B, subconfluent ST-2 cells were transfected with 9xNFAT-Luc and CMV/β-galactosidase reporter construct. Sixteen hours after the transfection, cells were switched to control medium or medium containing FK506 in A or to control medium or rhCTGF at 300 ng/ml in B and harvested after 24 h. In C, ST-2 cells were transfected with CTGF (black bars) or scrambled (white bars) siRNAs and with 9xNFAT-Luc and CMV/β-galactosidase reporter constructs, and harvested after 48 h. In D, ST-2 cells were transiently transfected with HES-1 or scrambled siRNA and with control pcDNA (white bars) or pcDNA-CTGF (black bars) and 9xNFAT-Luc and CMV/β-galactosidase reporter constructs, and harvested after 48 h. Bars represent means ± S.E. for six observations. Down-regulation of CTGF and HES-1 was documented in RNA extracted from parallel cultures and subjected to real-time RT-PCR. The ctgf copy number corrected for rpl38 was (means ± S.E.; n = 4) 2.9 ± 0.7 in control and 1.6 ± 0.2 in cells transfected with CTGF siRNA (p < 0.05), and the hes-1 copy number corrected for gapdh was (means ± S.E.; n = 3) 1.6 ± 0.2 in control and 0.5 ± 0.1 in cells transfected with HES-1 siRNA (p < 0.05). *, significantly different between control and CTGF and between control and CTGF down-regulated cells, p < 0.05. +, significantly different between control and FK506, p < 0.05. **, significantly different between control and HES-1 down-regulated cells, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Former studies have shown that cells of the osteoblastic lineage express transcripts for CTGF and other members of the CCN family of proteins (9). However, the function of CTGF in skeletal cells has been controversial, and stimulatory and inhibitory effects on osteoblastogenesis have been reported (10, 16). In the present study, we demonstrate that the constitutive overexpression of CTGF enhances osteoblast differentiation in cells of the osteoblastic lineage. CTGF overexpression induced the formation of mineralized nodules, alkaline phosphatase, and osteocalcin expression in ST-2 cells. The mechanism did not involve BMP or Wnt signaling. CTGF overexpression inhibited Notch signaling, induced HES-1 transcription by Notch-independent mechanisms, and enhanced the transactivation of NFAT. These three effects may help explain the stimulatory effect of CTGF on osteoblastogenesis in vitro.

CTGF is a member of the CCN superfamily of secreted CR peptides, which are related to selected BMP antagonists, such as Tsg and chordin (6–8). Previous studies have shown direct protein-protein interactions between CTGF and BMP-2, and similar interactions have been shown for Nov (16, 17, 19). However, Nov inhibits osteoblastogenesis by suppressing BMP-2 and Wnt signaling and activity, whereas CTGF overexpression in vitro favors osteoblastogenesis despite a modest decrease in BMP/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. These results indicate that the effect of CTGF on osteoblastogenesis is independent of BMP-2 and Wnt 3 signaling. Although CTGF is required for osteoblastogenesis, it can interact with BMP-2 and Wnt co-receptors and, under specific experimental conditions, alter BMP and Wnt signaling and activity (10, 16, 17). Dual permissive and inhibitory activity is not selective to CTGF, and it is shared by BMP antagonists of the Tsg/chordin family (50–54). The reason for the discrepancy in the results obtained among various reports is not clear, but it may be related to differences in the cells studied, in delivery systems, and experimental conditions. Transduction of C3H10T ½ mesenchymal cells with adenoviral vectors for the constitutive expression of CTGF or addition of CTGF to these cells results in impaired osteoblastogenesis (10, 16). In contrast, addition of CTGF was shown to promote the differentiation and function of osteoblast-like Saos-2 cells, MC3T3-E1 cells, and primary osteoblast cultures (13–16). In the present work, we have used a retroviral vector to deliver CTGF, which was expressed under the control of the CMV promoter, so that cells were continuously exposed to CTGF over a prolonged period of time. The different effects of CTGF in cells of the osteoblastic lineage may reflect the fact that different mechanisms may be operational in the various cells studied. It is possible that the inhibitory effect on BMP and Wnt signaling prevails when an inhibition of osteoblastogenesis is observed. This may also occur in vivo, and transgenic mice overexpressing CTGF under the control of the osteocalcin promoter exhibit osteopenia (55). In contrast, the stimulatory effect of CTGF may be observed when the inhibition of Notch signaling and the stimulation of HES-1 transcription and NFAT activity prevail. It is of interest that ctgf null mice have impaired vascularization and endochondral bone formation, indicating that CTGF is required for skeletal development (12). The phenotype is lethal not permitting the establishment of the function of CTGF in the adult skeleton. Observations in cultures of ctgf null osteoblastic calvarial cells indicate that CTGF is required for osteoblastogenesis and are in agreement with our results showing that forced overexpression of CTGF in vitro enhances osteoblastic differentiation (13).

CTGF inhibited the canonical Notch signaling pathway. Notch-ligand interactions result in the proteolytic cleavage of the Notch receptor and release of the intracellular domain, which translocates to the nucleus (38, 39). The intracellular domain subsequently interacts with members of the CSL family of transcription factors, leading to the induction of members of the HES and HERP families of intracellular proteins (38, 39). Notch inhibits osteoblastic differentiation, and CTGF overexpression inhibited the transactivation of a Notch reporter construct (5). The inhibition of Notch signaling may explain to some extent the stimulatory effect of CTGF on osteoblastogenesis. The mechanism of the inhibitory effect of CTGF on Notch signaling appears to involve the destabilization of the NICD protein following proteasome degradation. This contention is supported by the fact that the inhibition of Notch signaling was reversed by the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Despite an inhibition of Notch signaling, CTGF enhanced the transcription of HES-1. Notch induction of HES-1 is mediated by the association of NICD with RBP-Jk/CSL proteins. This was confirmed in cells from rbp-jk/csl null mice, where the forced overexpression of NICD failed to induce HES expression. However, even in the absence of RBP-Jk/CSL proteins there is a low level of HES-1 expression indicating that either Notch uses an alternate non-RBP-Jk/CSL-dependent pathway to induce HES-1, or that other signals, besides Notch, regulate HES-1 expression (56). This is in agreement with other observations documenting Notch-independent regulation of HES-1 transcription, which is regulated by the mitogen-activated protein kinases, Jun N-terminal kinase, and extracellular regulated kinases (ERKs) (57, 58). However, Jun N-terminal kinase, or ERK inhibitors did not prevent the stimulatory effect of CTGF on HES-1 transcription (data not shown), suggesting that alternate mechanisms are responsible for the induction of HES-1 by CTGF.

In previous studies we demonstrated that overexpression of NICD inhibits osteoblastogenesis by opposing the effect of Wnt on the Wnt/β-catenin canonical signaling pathway (5). HES-1 is a major downstream target gene of Notch signaling, and previous studies from our laboratory suggested that HES-1 plays a partial role in the inhibitory effects of NICD on Wnt/β-catenin signaling (5, 38, 39). However, forced overexpression of HES-1 does not inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling and enhances osteoblastogenesis. The discordant effects of HES-1 on osteoblastogenesis observed following its down-regulation and forced overexpression may reflect a dual role of this factor in osteoblastic cell differentiation, as it was reported for adipogenesis (59). The dual effects observed in cells of the osteoblastic lineage are the converse of those obtained in pre-adipocytic cells, where down-regulation of HES-1 using RNAi inhibits adipogenesis, indicating an obligatory role for HES-1 in adipocyte differentiation. In contrast, forced overexpression of HES-1 inhibits adipogenesis by suppressing preadipocyte factor-1 (59). These observations also are in agreement with the concept that precursor mesenchymal cells can be directed to differentiate either toward the osteoblastic or adipocytic pathway, and HES-1 may play a role in mesenchymal cell fate decision.

Our results, demonstrating that forced overexpression of HES-1 does not cause overlapping effects with Notch, are in line with reports in C2C12 cells, where Notch inhibits myogenesis, but forced overexpression of HES-1 does not recapitulate the effects of Notch (60). These observations confirm that, even though Notch induces HES-1 in cells of the osteoblastic lineage, the inhibitory effects of Notch 1 are likely mediated by HES-1 and by alternate Notch-dependent signals. These may include the Notch effector HERP-2, because this Notch-dependent factor inhibits osteoblastogenesis (49). Our findings are concordant with the notion that HES-1 may not be the primary effector of Notch activity in all mammalian cells.

HES-1 overexpression did not modify BMP/Smad signaling, or the Wnt/β-catenin canonical signaling pathway, both considered central to osteoblastic differentiation. However, HES-1 induced the transactivation of NFAT, and it was in part required for CTGF-dependent transactivation of NFAT. Calcineurin is a calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase that dephosphorylates NFAT and promotes its nuclear localization (61). Calcineurin activity is suppressed by calcipressin. Calcineurin and NFAT play a role in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation, and CTGF and HES-1 enhanced NFAT transactivation by a calcineurin-dependent mechanism (47, 48). HES-1 and HERP-2 had opposing effects on the transactivation of NFAT, and HES-1 caused a modest decrease in HERP-2 binding to DNA consensus sequences, possibly by forming heterodimers with HERP-2. Consequently, the stimulatory effect of HES-1 on NFAT transactivation may be to an extent secondary to its heterodimerization with HERP-2, so that less HERP-2 is available to inhibit NFAT transactivation (49). Because HES-1 caused only a modest decrease in the binding of HERP-2 to its recognition sequences in EMSAs, it is probable that additional mechanisms are involved in the induction of NFAT by HES-1. NFAT induces osteoblastogenesis, and its induction by CTGF and HES-1 may be mechanistically relevant to their activities in cells of the osteoblastic lineage (30). Our results suggest that HES-1 is downstream of CTGF and upstream of NFAT, although CTGF appears to induce NFAT by HES-1-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

In conclusion, our studies demonstrate that CTGF enhances osteoblastic cell differentiation in vitro, possibly by inhibiting Notch signaling, inducing HES-1 transcription, and activating NFAT signaling.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Zhao for providing the 12xSBE-Oc-pGL3 construct; L. J. Strobl for the 12xCSL-Luc reporter construct; U. Lendahl for the HES-1 promoter construct; J. D. Molkentin for the 9xNFAT-Luc construct; T. Iso for the HERP-2 expression construct; Wyeth Research for BMP-2 and the 16xTCF-Luc construct; R. P. Rysek for CTGF cDNA; R. Wu for GAPDH cDNA; Leah Brown, Emily Paul, and Melissa Burton for technical help; and Mary Yurczak for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK42424 and DK45227 from NIDDK. This work was also supported by Grant AR21707 from the NIAMS, NIH. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; APA, alkaline phosphatase activity; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CR, cysteine-rich; CSL, CBF1/Suppressor of Hairless/Lag 1; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; Cyr 61, cysteine-rich 61; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HES-1, hairy and E (spl)-1; HERP, HES-related repressor protein; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunopurified; LEF, lymphoid enhancer binding factor; MEM, minimum essential medium; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; NICD, Notch intracellular domain; Nov, Nephroblastoma overexpressed; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; rhCTGF, recombinant human CTGF; RNAi, RNA interference; RPL38, ribosomal protein L38; RT, reverse transcription; SBE, Smad binding element; Smad, signaling mothers against decapentaplegic; TCF, T cell-specific factor; TGF, transforming growth factor; Tsg, twisted gastrulation.

References

- 1.Bianco, P., and Gehron, R. P. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 105 1663-1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thies, R. S., Bauduy, M., Ashton, B. A., Kurtzberg, L., Wozney, J. M., and Rosen, V. (1992) Endocrinology 130 1318-1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh-Choudhury, N., Harris, M. A., Feng, J. Q., Mundy, G. R., and Harris, S. E. (1994) Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 4 345-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westendorf, J. J., Kahler, R. A., and Schroeder, T. M. (2004) Gene (Amst.) 341 19-39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deregowski, V., Gazzerro, E., Priest, L., Rydziel, S., and Canalis, E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 6203-6210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brigstock, D. R. (2003) J. Endocrinol. 178 169-175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brigstock, D. R., Goldschmeding, R., Katsube, K. I., Lam, S. C., Lau, L. F., Lyons, K., Naus, C., Perbal, B., Riser, B., Takigawa, M., and Yeger, H. (2003) Mol. Pathol. 56 127-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia, A. J., Coffinier, C., Larrain, J., Oelgeschlager, M., and De Robertis, E. M. (2002) Gene 287 39-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parisi, M. S., Gazzerro, E., Rydziel, S., and Canalis, E. (2006) Bone 38 671-677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo, Q., Kang, Q., Si, W., Jiang, W., Park, J. K., Peng, Y., Li, X., Luu, H. H., Luo, J., Montag, A. G., Haydon, R. C., and He, T. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 55958-55968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira, R. C., Durant, D., and Canalis, E. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 279 E570-E576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivkovic, S., Yoon, B. S., Popoff, S. N., Safadi, F. F., Libuda, D. E., Stephenson, R. C., Daluiski, A., and Lyons, K. M. (2003) Development 130 2779-2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaki, H., Kubota, S., Suzuki, A., Yamada, T., Matsumura, T., Mandai, T., Yao, M., Maeda, T., Lyons, K. M., and Takigawa, M. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 366 450-456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishida, T., Nakanishi, T., Asano, M., Shimo, T., and Takigawa, M. (2000) J. Cell Physiol. 184 197-206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safadi, F. F., Xu, J., Smock, S. L., Kanaan, R. A., Selim, A. H., Odgren, P. R., Marks, S. C., Jr., Owen, T. A., and Popoff, S. N. (2003) J. Cell Physiol. 196 51-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abreu, J. G., Ketpura, N. I., Reversade, B., and De Robertis, E. M. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4 599-604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercurio, S., Latinkic, B., Itasaki, N., Krumlauf, R., and Smith, J. C. (2004) Development 131 2137-2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latinkic, B. V., Mercurio, S., Bennett, B., Hirst, E. M., Xu, Q., Lau, L. F., Mohun, T. J., and Smith, J. C. (2003) Development 130 2429-2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rydziel, S., Stadmeyer, L., Zanotti, S., Durant, D., Smerdel-Ramoya, A., and Canalis, E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 19762-19772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sciaudone, M., Gazzerro, E., Priest, L., Delany, A. M., and Canalis, E. (2003) Endocrinology 144 5631-5639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otsuka, E., Yamaguchi, A., Hirose, S., and Hagiwara, H. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277 C132-C138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudo, H., Kodama, H. A., Amagai, Y., Yamamoto, S., and Kasai, S. (1983) J. Cell Biol. 96 191-198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nazarenko, I., Lowe, B., Darfler, M., Ikonomi, P., Schuster, D., and Rashtchian, A. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30 e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nazarenko, I., Pires, R., Lowe, B., Obaidy, M., and Rashtchian, A. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30 2089-2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lian, J., Stewart, C., Puchacz, E., Mackowiak, S., Shalhoub, V., Collart, D., Zambetti, G., and Stein, G. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86 1143-1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tso, J. Y., Sun, X. H., Kao, T. H., Reece, K. S., and Wu, R. (1985) Nucleic Acids Res. 13 2485-2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahl, L. K. (1952) Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 80 474-479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iso, T., Sartorelli, V., Chung, G., Shichinohe, T., Kedes, L., and Hamamori, Y. (2001) Mol. Cell Biol. 21 6071-6079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strom, A., Castella, P., Rockwood, J., Wagner, J., and Caudy, M. (1997) Genes Dev. 11 3168-3181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schreiber, E., Matthias, P., Muller, M. M., and Schaffner, W. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17 6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gazzerro, E., Pereira, R. C., Jorgetti, V., Olson, S., Economides, A. N., and Canalis, E. (2005) Endocrinology 146 655-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persson, U., Izumi, H., Souchelnytskyi, S., Itoh, S., Grimsby, S., Engstrom, U., Heldin, C. H., Funa, K., and ten Dijke, P. (1998) FEBS Lett. 434 83-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishisaki, A., Yamato, K., Hashimoto, S., Nakao, A., Tamaki, K., Nonaka, K., ten Dijke, P., Sugino, H., and Nishihara, T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 13637-13642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young, C. S., Kitamura, M., Hardy, S., and Kitajewski, J. (1998) Mol. Cell Biol. 18 2474-2485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao, M., Qiao, M., Harris, S. E., Oyajobi, B. O., Mundy, G. R., and Chen, D. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 12854-12859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Billiard, J., Way, D. S., Seestaller-Wehr, L. M., Moran, R. A., Mangine, A., and Bodine, P. V. (2005) Mol. Endocrinol. 19 90-101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nam, Y., Sliz, P., Song, L., Aster, J. C., and Blacklow, S. C. (2006) Cell 124 973-983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson, J. J., and Kovall, R. A. (2006) Cell 124 985-996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strobl, L. J., Hofelmayr, H., Stein, C., Marschall, G., Brielmeier, M., Laux, G., Bornkamm, G. W., and Zimber-Strobl, U. (1997) Immunobiology 198 299-306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lardelli, M., and Lendahl, U. (1993) Exp. Cell Res. 204 364-372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai, Y. S., Xu, J., and Molkentin, J. D. (2005) Mol. Cell Biol. 25 9936-9948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharp, P. A. (2001) Genes Dev. 15 485-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elbashir, S. M., Harborth, J., Lendeckel, W., Yalcin, A., Weber, K., and Tuschl, T. (2001) Nature 411 494-498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira, R. C., Delany, A. M., and Canalis, E. (2004) Endocrinology 145 1952-1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mammucari, C., Tommasi, d., V, Sharov, A. A., Neilson, J., Havrda, M. C., Roop, D. R., Botchkarev, V. A., Crabtree, G. R., and Dotto, G. P. (2005) Dev. Cell 8 665-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koga, T., Matsui, Y., Asagiri, M., Kodama, T., de Crombrugghe B., Nakashima, K., and Takayanagi, H. (2005) Nat. Med. 11 880-885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun, L., Blair, H. C., Peng, Y., Zaidi, N., Adebanjo, O. A., Wu, X. B., Wu, X. Y., Iqbal, J., Epstein, S., Abe, E., Moonga, B. S., and Zaidi, M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 17130-17135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zamurovic, N., Cappellen, D., Rohner, D., and Susa, M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 37704-37715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gazzerro, E., Deregowski, V., Vaira, S., and Canalis, E. (2005) Endocrinology 146 3875-3882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ross, J. J., Shimmi, O., Vilmos, P., Petryk, A., Kim, H., Gaudenz, K., Hermanson, S., Ekker, S. C., O'Connor, M. B., and Marsh, J. L. (2001) Nature 410 479-483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang, C., Holtzman, D. A., Chau, S., Chickering, T., Woolf, E. A., Holmgren, L. M., Bodorova, J., Gearing, D. P., Holmes, W. E., and Brivanlou, A. H. (2001) Nature 410 483-487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nosaka, T., Morita, S., Kitamura, H., Nakajima, H., Shibata, F., Morikawa, Y., Kataoka, Y., Ebihara, Y., Kawashima, T., Itoh, T., Ozaki, K., Senba, E., Tsuji, K., Makishima, F., Yoshida, N., and Kitamura, T. (2003) Mol. Cell Biol. 23 2969-2980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gazzerro, E., Deregowski, V., Stadmeyer, L., Gale, N. W., Economides, A. N., and Canalis, E. (2006) Bone 39 1252-1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smerdel-Ramoya, A., Zanotti, S., Stadmeyer, L., and Canalis, E. (2007) J. Bone Miner Res. 22 Suppl. 1, S51 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iso, T., Kedes, L., and Hamamori, Y. (2003) J. Cell Physiol. 194 237-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stockhausen, M. T., Sjolund, J., and Axelson, H. (2005) Exp. Cell Res. 310 218-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Curry, C. L., Reed, L. L., Nickoloff, B. J., Miele, L., and Foreman, K. E. (2006) Lab. Invest. 86 842-852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ross, D. A., Rao, P. K., and Kadesch, T. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24 3505-3513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nofziger, D., Miyamoto, A., Lyons, K. M., and Weinmaster, G. (1999) Development 126 1689-1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Graef, I. A., Chen, F., and Crabtree, G. R. (2001) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11 505-512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]