Abstract

We recently described a novel basal bacterial promoter element that is located downstream of the –10 consensus promoter element and is recognized by region 1.2 of the σ subunit of RNA polymerase (RNAP). In the case of Thermus aquaticus RNAP, this element has a consensus sequence GGGA and allows transcription initiation in the absence of the –35 element. In contrast, the Escherichia coli RNAP is unable to initiate transcription from GGGA-containing promoters that lack the –35 element. In the present study, we demonstrate that σ subunits from both E. coli and T. aquaticus specifically recognize the GGGA element and that the observed species specificity of recognition of GGGA-containing promoters is determined by the RNAP core enzyme. We further demonstrate that transcription initiation by T. aquaticus RNAP on GGGA-containing promoters in the absence of the –35 element requires σ region 4 and C-terminal domains of the α subunits, which interact with upstream promoter DNA. When in the context of promoters containing the –35 element, the GGGA element is recognized by holoenzyme RNAPs from both E. coli and T. aquaticus and increases stability of promoter complexes formed on these promoters. Thus, GGGA is a bona fide basal promoter element that can function in various bacteria and, depending on the properties of the RNAP core enzyme and the presence of additional promoter elements, determine species-specific differences in promoter recognition.

In bacteria, recognition of promoters is accomplished through specific interactions of the RNA polymerase (RNAP)3 holoenzyme with consensus elements of promoter DNA. Most housekeeping promoters are recognized by RNAP holoenzyme containing the major σ subunit (called σ70 in Escherichia coli or σA in other bacteria). The –10 (TATAAT) and the –35 (TTGACA) consensus elements of these promoters interact with conserved regions 2.4 and 4.2 of σ, respectively (1). A subset of promoters (the so-called extended –10 promoters) contain a TG motif one nucleotide upstream of the –10 element that is recognized by region 2.5 of σ; these promoters do not require the –35 element for their activity (2). Some strong promoters contain an A/T-rich UP element that is located upstream of the –35 element and is specifically recognized by the C-terminal domains of the RNAP α subunits (αCTDs) (3).

In addition to specific interactions with conserved promoter elements, nonspecific RNAP-DNA interactions also contribute to promoter recognition. In particular, it was shown that nonspecific contacts of E. coli RNAP αCTDs with upstream DNA play an important role in promoter recognition even in the absence of the UP element (4–6) and that contacts of σ70 region 4 with DNA stimulate recognition of extended –10 promoters lacking the –35 element (7).

Sigma subunits of the σ70 class are unable to recognize promoters in the absence of the RNAP core. We have recently demonstrated that isolated σA from thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus can recognize single-stranded DNA aptamers (sTaps, for sigma T. aquaticus aptamers) that contain a –10-like element followed by the tetranucleotide motif GGGA (8). Using site-specific DNA-protein cross-linking, we demonstrated that the GGGA motif interacts with region 1.2 of σA. Furthermore, double-stranded DNA fragments based on sTap sequences served as efficient promoters for T. aquaticus RNAP holoenzyme, and their recognition depended on the presence of the GGGA motif but did not require the presence of the –35 promoter element or the TG motif characteristic of extended –10 promoters. Thus, the GGGA motif is a bona fide basal promoter element for T. aquaticus RNAP. Indeed, we found that similar motifs are present in natural promoters and increase stability of promoter complexes of RNAPs from T. aquaticus and related bacteria (8). Bioinformatics analysis suggested that up to 33% of predicted promoters in the genome of Thermus thermophilus contain GGGA-like motifs. In contrast, no preference for such motifs was found in E. coli promoter sequences (8).

In a parallel study, it was shown that E. coli RNAP σ70 holoenzyme can also specifically recognize promoter region immediately downstream of the –10 consensus element (9). Because of the apparent ability of this promoter region to mediate stringent response-dependent inhibition of transcription from E. coli rRNA and tRNA promoters, it was termed “discriminator” (10). Substitutions in this region (including a C to G substitution in this region 2 base pairs downstream of the –10 element) in the E. coli rrnB P1 promoter were demonstrated to dramatically increase promoter complex stability (9). Furthermore, residues 99–107 from σ70 region 1.2 cross-linked to photoreactive G-nucleotide analogues introduced one and two base pairs downstream of –10 elements of rrnB P1 and λ PR promoters (9, 11). Therefore, G nucleotides at these positions are likely specifically recognized by σ70 region 1.2, and this interaction apparently stabilizes promoter complexes.

Surprisingly, however, RNAPs from T. aquaticus and E. coli were found to differ in recognition of promoters containing the GGGA element (8). Although in the case of T. aquaticus RNAP, the –10 element and the GGGA element were sufficient for transcription initiation, E. coli RNAP required the –35 element whether the GGGA element was present or not. In the present study, we investigated the mechanisms underlying the observed species specificity of promoter recognition and analyzed the roles of different structural elements of the T. aquaticus RNAP holoenzyme in the recognition of promoters containing the GGGA element.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

RNAP Purification—Wild type E. coli and T. aquaticus core RNAPs were purified as described in Refs. 12 and 13. The T. aquaticus core RNAP with deletion of the β′ nonconserved domain (β′NCD, amino acids 159–453) was purified from E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells overexpressing all four core RNAP subunits from the plasmid pET28rpoABCd0ZTaq as described in Ref. 14. T. aquaticus core RNAP with deletion of αCTDs and T. aquaticus RNAP containing αCTDs from E. coli were purified from E. coli cells overexpressing core RNAP subunits from the plasmids pET28rpoA(ΔCTD)BCd0ZTaq and pET28rpoA(TE)BCd0ZTaq that contained a truncated version of the rpoA gene (codons 1 through 230) and the hybrid rpoA gene (T. aquaticus codons 1–230 and E. coli codons 234–329), respectively. The T. aquaticus RNAP with deletion of the β flexible flap domain (amino acids 757–786) identical to the E. coli RNAP flap deletion (15, 16) was purified from E. coli cells containing the plasmid pET28rpoAB(ΔF)CTaq. The gene coding for the chimeric σ eT subunit that contained the N-terminal part from E. coli σ70 (amino acids 1–127) and the C-terminal part from T. aquaticus σA (amino acids 126–438) was obtained by PCR mutagenesis and cloned between the NdeI and EcoRI sites into pET28. The mutant σ subunit and wild type E. coli σ70 and T. aquaticus σA (all containing His6 tags in their N termini) were overexpressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) and purified as described in Ref. 17.

Oligonucleotide Selection—The selection of aptamers was performed essentially as described in Ref. 8. The library used for the selection was based on the sequence of the 75-nucleotide-long sTap2 aptamer and contained a random region in place of the GGGA motif (see Fig. 2A). The library (100 pmol) was incubated with either wild type T. aquaticus σA or chimeric σ eT in 300 μl of binding buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 10 mm MgCl2, 240 mm NaCl, and 60 mm KCl for 30 min at 25 °C. 15 μl of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) was added, and incubation continued for 20 min with occasional shaking. The sorbent was washed three times with 1 ml of binding buffer (for a total time of 30 min), and the σ-DNA complexes were eluted with 300 μl of binding buffer containing 200 mm imidazole. The eluted DNA was amplified using primers corresponding to fixed regions of the library (PL, 5′-GGGAGCTCAGAATAAACGCTCAA; PR, BBB-5′-GATCCGGGCCTCATGTCGAA, where B is a biotin residue). Two DNA strands were separated by size on 10% denaturing PAGE, and the non-biotinylated strand was used for the next round of selection. After three rounds of selection, the enriched library was amplified with primers containing EcoRI and HindIII sites and cloned into the pUC19 plasmid.

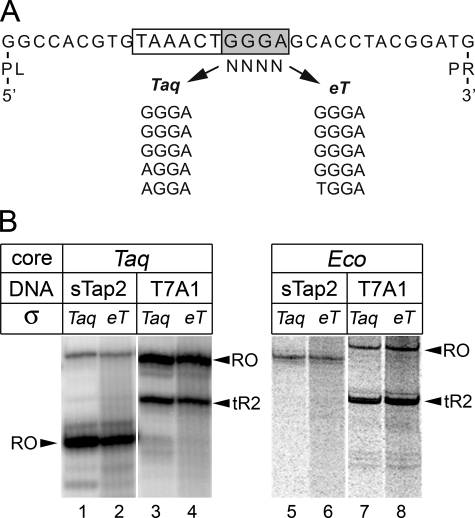

FIGURE 2.

The E. coli σ70 subunit region 1.2 is able to specifically recognize the GGGA motif. A, selection of sequences specifically recognized by region 1.2 of the E. coli σ70 subunit. The sequence of the T. aquaticus σA sTap2 aptamer is shown at the top of the figure. PL and PR designate sequences corresponding to primers used for amplification of the library during aptamer selection (see “Experimental Procedures”). The –10-like element is boxed, and the GGGA motif is shadowed. Sequences of the GGGA region in the aptamer variants selected against wild type T. aquaticus σA and the σ eT chimera are shown below the sequence. B, activity of T. aquaticus (left panel) and E. coli (right panel) RNAPs containing wild type σA and σ eT on the sTap2 and T7 A1 promoters. Transcription was performed at 60 °C for T. aquaticus RNAP and 37 °C for E. coli RNAP. Positions of the run-off (RO) and terminated RNA products are indicated by arrowheads.

In Vitro Transcription—Double-stranded DNA fragments containing aptamer sequences were prepared by PCR from the aptamer pUC19 clones as described (8). The T7 A1 and galP1 promoter templates were described previously (7, 18). Transcription was performed in a buffer containing 40 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 40 mm KCl, and 10 mm MgCl2. Holoenzymes were prepared by incubating the core enzyme (100 nm) with σ (500 nm) for 5 min at 25 °C. Promoter DNA fragments were added to 50 nm, and the samples were incubated for 15 min at temperatures indicated in the figure legends. NTPs were added to 100 μm (including 2.5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP), and transcription was performed for 10 min. In open complex stability measurements, heparin was added (50 μg/ml) at different time points prior to NTP addition, and the transcription reaction was performed for 3 min. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 μl of a stop buffer containing 8 m urea and 20 mm EDTA. The RNA products were separated by 15% denaturing PAGE and analyzed by phosphorimaging.

RESULTS

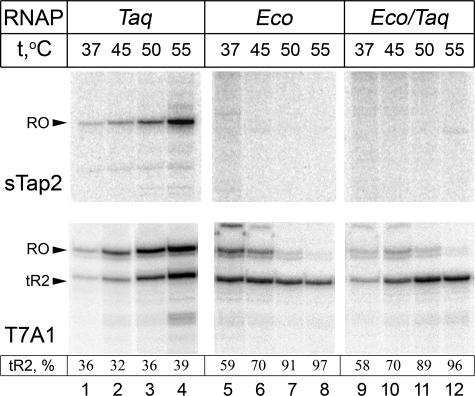

The Specificity of Recognition of GGGA-containing Promoters Is Determined by the Core Enzyme of RNAP—In our previous study, we demonstrated that T. aquaticus σA RNAP holoenzyme but not E. coli σ70 RNAP holoenzyme is able to initiate transcription on synthetic promoters based on aptamers specific to σA (sTaps) (8). Recognition of these promoters by T. aquaticus σA RNAP holoenzyme depends on the GGGA element located immediately downstream of the –10 promoter consensus element and does not require either the –35 or the TG promoter elements. The ability of thermophilic T. aquaticus RNAP but not the mesophilic E. coli RNAP to initiate transcription on sTap-based promoters could be due to higher temperature optimum of the former enzyme, because high temperature facilitates DNA melting, including localized melting of promoter DNA. To test the role of reaction temperature on transcription from sTap promoters, we performed transcription on one of the promoters, sTap2, with E. coli and T. aquaticus RNAPs at temperatures varying from 37 to 55 °C (Fig. 1). As a control, we analyzed the temperature dependence of transcription from the T7 A1 promoter, a strong –10/–35 class promoter. Because the control template also contained a downstream λ tR2 terminator, transcription from this template resulted in two (terminated and “run-off”) transcripts. We found that T. aquaticus RNAP was active on both templates at all of the temperatures tested, although its activity at 37 °C was much lower than at 55 °C, as expected (Fig. 1, lanes 1–4). In contrast, E. coli RNAP, although active on the T7 A1 promoter at all of the temperatures tested (Fig. 1, lanes 5–8, lower panel), was unable to transcribe from sTap2 (Fig. 1, lanes 5–8, upper panel). Thus, the absence of transcription from the sTap template by the E. coli RNAP (and conversely, efficient transcription by the T. aquaticus enzyme from this template) cannot be explained by nonspecific stimulation of promoter melting at high temperature.

FIGURE 1.

Activity of T. aquaticus and E. coli RNA polymerases on the sTap2 and T7A1 promoters. Transcription was performed with wild type T. aquaticus (Taq) and E. coli (Eco) holoenzymes and with a hybrid holoenzyme consisting of E. coli core and T. aquaticus σA (Eco/Taq) on the sTap2 (upper panels) and T7 A1 (lower panels) promoters as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The termination efficiency on the tR2 terminator is shown below the figure (as a percentage of the amount of terminated transcript relative to the sum of terminated and run-off transcripts).

In agreement with published data (19), the efficiency of transcription termination (measured as a ratio of the terminated transcript to the sum of terminated and run-off transcripts) by E. coli core RNAP on λ tR2 was dramatically increased at high temperatures (Fig. 1, lower panel, lanes 5–8 and 9–12). In contrast, termination efficiency of T. aquaticus RNAP did not depend on temperature within the range studied (Fig. 1, lower panel, lanes 1–4). The result may indicate that at high temperatures, elongation complexes of T. aquaticus RNAP are more stable than E. coli RNAP complexes. Such higher stability may be adaptive for an obligate thermophile such as T. aquaticus and allow the synthesis of full-sized transcripts to occur.

Because the GGGA element was first identified in single-stranded DNA aptamers specific to T. aquaticus σA subunit, one could expect that the inability of E. coli RNAP holoenzyme to initiate transcription on promoters containing this element is entirely due to the inability of σ70 to recognize this element. To test this, we analyzed transcription by a hybrid holoenzyme consisting of E. coli core and T. aquaticus σA. This RNAP was active on the T7 A1 promoter at all of the temperatures tested but was unable to initiate transcription on the sTap2 promoter (Fig. 1, lanes 9–12). Thus, T. aquaticus σA cannot promote transcription initiation on sTap2 by E. coli core, even though it recognizes the GGGA element both in aptamers and, in the context of T. aquaticus RNAP holoenzyme, in promoters. The result thus suggests that the inability of E. coli σ70 holoenzyme to recognize the sTap2 promoter is determined by the core enzyme and not by the σ70 subunit.

E. coli σ70 Region 1.2 Specifically Recognizes the GGGA Element in Aptamers and Promoters—Because E. coli σ70 does not form an active holoenzyme with T. aquaticus core RNAP (12, 13), we could not directly test its ability to recognize sTap-based promoters in complex with T. aquaticus RNAP core. Therefore, to analyze the specificity of σ70 interactions with DNA immediately downstream of the –10 element, we performed in vitro oligonucleotide selection using a library based on the previously characterized σA-specific sTap2 aptamer in which the region corresponding to the GGGA element was randomized (Fig. 2A). It should be noted that specific recognition of sTap2 by the σA subunit depends on aptamer contacts with several parts of the σ subunit, including regions 1.2, 2, and 4 (Ref. 8 and unpublished data). Thus, to specifically probe the interactions of σ70 region 1.2 with the GGGA element, we performed oligonucleotide selection using a chimeric σA subunit in which the N-terminal part, including the entire region 1.2, was replaced with a corresponding sequence from σ70 (σ eT, E. coli σ70 amino acids 1–127 introduced instead of T. aquaticus σA amino acids 1–125). As a control, we performed the same selection with wild type σA. After three rounds of selection, enriched libraries were cloned, and sequences of five randomly chosen clones from each library were determined. In both cases, most clones contained the original GGGA motif (Fig. 2A). The result suggests that σ70 region 1.2 recognizes the GGGA element in single-stranded DNA aptamers with the same specificity as region 1.2 of T. aquaticus σA.

We next asked whether σ70 region 1.2 can also recognize the GGGA element in sTap-based promoters. To test this, we performed transcription from an sTap2-based template using RNAP holoenzyme reconstituted from T. aquaticus core enzyme and chimeric σ subunit eT (Fig. 2B). The reconstituted holoenzyme efficiently transcribed from both the T7 A1 control template and from the sTap2 promoter template (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 4). Thus, when in the context of T. aquaticus RNAP holoenzyme, σ70 region 1.2 is able to recognize the GGGA element in the sTap2 promoter. At the same time, holoenzyme reconstituted from the E. coli core enzyme, and the σ eT subunit was unable to transcribe from the sTap2 template (Fig. 2B, lane 6), thus providing additional evidence that the inability of E. coli RNAP to recognize this promoter is determined by the core enzyme.

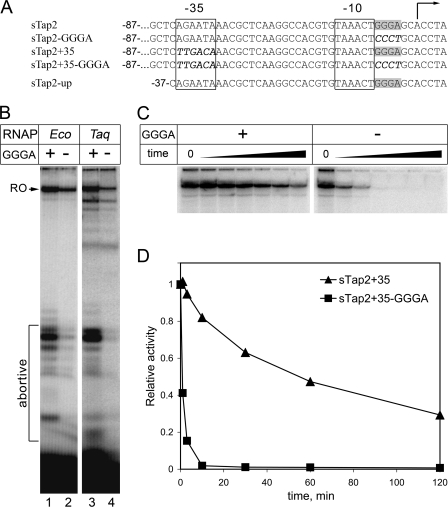

The GGGA Element Stabilizes Promoter Complexes Formed by the E. coli σ70 RNAP Holoenzyme—The results of experiments presented in the previous section demonstrate that region 1.2 of E. coli σ70 can specifically recognize the GGGA element both in single-stranded aptamers and in sTap-based promoters. Because the E. coli σ70 holoenzyme RNAP is inactive on GGGA-containing promoters lacking the –35 element, we asked whether it can specifically recognize this element when the –35 element is present. To test this, we analyzed transcription by the E. coli σ70 RNAP holoenzyme from two variants of the sTap2 promoter containing consensus –35 promoter element introduced 18 nucleotides upstream of the –10 element (8). Previously, we demonstrated that the –35 element artificially placed at this promoter position in galP1 and sTap2 templates could be efficiently recognized by E. coli RNAP (7, 8). The first variant, sTap2+35, contained both the GGGA element and the –35 element; the second, sTap2+35-GGGA, contained the –35 element but had the GGGA sequence replaced with CCCT (Fig. 3A). In agreement with published data (8), E. coli RNAP efficiently transcribed from both promoters; the amount of run-off transcript synthesized from the template containing the GGGA element was higher (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2). Remarkably, the amount of abortive transcripts (and the ratio of abortive to run-off transcripts) produced on the sTap2+35 template was much higher than that produced on sTap2+35-GGGA. Likewise, the T. aquaticus RNAP holoenzyme also synthesized much larger amounts of abortive RNAs on sTap2+35 compared with sTap2+35-GGGA (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). This indicated that in the presence of the –35 element, the GGGA element hinders promoter escape, presumably because it introduces additional point(s) of contact of RNAP with the promoter.

FIGURE 3.

The GGGA motif is recognized by the E. coli RNAP holoenzyme. A, sequences of sTap2 variants used in transcription experiments. Nucleotides corresponding to the –10 and –35 promoter elements are boxed. The GGGA motif is shown in gray. The starting point of transcription is indicated by an arrow. The upper four variants of sTap2 contain nucleotides from –87 to +86, and the lower variant contains nucleotides from –37 to +86 relative to the start of transcription. Nucleotides changed in the mutant derivatives of sTap2 are bold italics. B, activity of wild type E. coli (Eco) and T. aquaticus (Taq) RNAPs on two variants of the sTap2 promoter containing the –35 element and either containing (+, sTap2+35) or lacking the GGGA motif (–, sTap2+35-GGGA). Transcription was performed at 37 °C for E. coli RNAP and at 60 °C for T. aquaticus RNAP. The positions of the run-off RNA transcript (RO) and abortive products are shown on the left of the figure. C, analysis of stability of promoter complexes formed by σ70 E. coli RNAP holoenzyme on the sTap2+35 and sTap2+35-GGGA promoters. The activity of promoter complexes was measured at different time points after heparin addition; activity in the control sample (zero time point) was measured in the absence of heparin (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). D, dissociation kinetics of E. coli RNAP promoter complexes (data from C). At each time point, the activity is shown as a fraction of activity measured in the absence of heparin.

We have previously reported that the GGGA element increases the stability of promoter complexes formed by T. aquaticus RNAP on promoters containing the –35 element (8). To test whether the GGGA element could play a similar role in promoter recognition by E. coli RNAP holoenzyme, we compared lifetimes of promoter complexes formed by E. coli σ70 holoenzyme on sTap2+35 and sTap2+35-GGGA promoters. The stabilities of promoter complexes were measured in a run-off transcription assay in the presence of heparin that was added at different time points prior to nucleotide addition (Fig. 3C). We found that complexes formed on sTap2+35 were stable and dissociated with a half-life of about 1 h. In contrast, complexes formed on sTap2+35-GGGA were highly unstable, with a half-life of less than 1 min (Fig. 3D). Thus, the GGGA element greatly stabilizes promoter complexes formed by E. coli RNAP holoenzyme on the –10/–35 type promoters.

Recognition of Promoters Containing the GGGA Element by T. aquaticus RNAP Depends on the Presence of σ Region 4, αCTDs, and the β Flap Domain—Because σ subunits of both T. aquaticus and E. coli RNAPs recognize the GGGA element but only the former enzyme can initiate transcription from GGGA-containing promoters in the absence of the –35 element, specific RNAP interactions with GGGA cannot be sufficient for efficient recognition of this type of promoters. Previous studies demonstrated that nonspecific RNAP contacts with upstream promoter sequences play an essential role in promoter recognition by E. coli RNAP (see Introduction). In particular, nonspecific contacts of αCTDs and σ region 4 with promoter DNA increase the efficiency of transcription initiation on different types of promoters (5–7). Furthermore, in the context of the E. coli σ70 RNAP holoenzyme, the flexible flap domain of the β subunit is required for proper positioning of σ region 4 to allow efficient recognition of the –35 promoter element (16). This suggests that the β flap may also promote nonspecific interactions of σ region 4 with DNA; however, this conjecture has not been tested directly. Finally, T. aquaticus core RNAP contains an insertion of a large nonconserved domain at the N terminus of the β′ subunit (β′NCD), which interacts with the σ subunit (in a nonconserved segment between regions 1 and 2) (14, 20). The β′NCD might therefore also contribute to the specificity of promoter recognition.

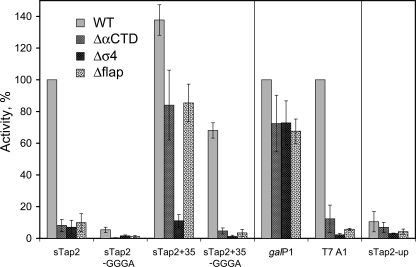

To assess the role of these RNAP domains in the recognition of GGGA-containing promoters by T. aquaticus RNAP, we analyzed T. aquaticus RNAP mutants with deletions of β′NCD (Δβ′NCD, β′ amino acids 159–453 removed), αCTDs (ΔαCTD, α amino acids 230–313 removed; this RNAP also harbored deletion of the β′NCD), region 4.2 of the σA subunit (Δσ4, σ amino acids 391–438 removed), and the β flap domain (Δβflap, β amino acids 757–786 removed). The activities of the wild type and mutant T. aquaticus RNAPs on different variants of the sTap2 promoter were compared with activities on control promoters T7 A1 and galP1 (an extended –10 promoter). The variants of the sTap2 promoter included wild type sTap2, sTap2-GGGA (in which the GGGA element was replaced with CCCT), sTap2+35, and sTap2+35-GGGA (Fig. 3A). The results are presented in Fig. 4. In agreement with previous work (8), wild type T. aquaticus RNAP did not initiate transcription on the sTap2 variant lacking the GGGA element (sTap2-GGGA) but was active on sTap2 variants containing the –35 element both in the presence and in the absence of GGGA (although the activity on the latter template was lower than on the former). Thus, the –35 element allows recognition of sTap-based promoters by T. aquaticus RNAP in the absence of GGGA. RNAP with deletion of β′NCD did not significantly differ from wild type T. aquaticus RNAP in recognition of all promoters tested (data not shown). Thus, this RNAP domain does not contribute to specific promoter recognition. In contrast, the ΔαCTD RNAP showed very low levels of activity on wild type sTap2, sTap2-GGGA, and sTap2+35-GGGA templates but transcribed well from the sTap2+35 promoter (contains both the –35 element and the GGGA element) (Fig. 4). RNAP with deletion of the β flap domain behaved similarly to the ΔαCTD mutant (Fig. 4). The Δσ4 RNAP (reconstituted from wild type core and σA lacking region 4) had about 10-fold lower activity than the wild type RNAP on sTap2 variants containing the GGGA element and was essentially inactive on sTap2 variants lacking GGGA. All three mutant RNAPs did not recognize the T7 A1 promoter but showed high levels of activity on the galP1 template (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Activity of mutant variants of T. aquaticus RNAP with deletions of αCTDs, σ region 4, and the β flap on various promoters. Transcription was performed at 60 °C. RNAP activities (run-off RNA synthesis) on different variants of the sTap2 promoter are shown as percentages of activity of wild type (WT) RNAP on the wild type sTap2 promoter. Activities on galP1 and T7 A1 promoters are shown as percentages of activity of wild type T. aquaticus RNAP on each of the promoters. The average values and standard deviations from three to five independent experiments are shown.

From these data, the following conclusions can be drawn: (i) T. aquaticus RNAP αCTDs, σ region 4, and β flap are not critically important for recognition of the extended –10 class galP1 promoter. (ii) Initiation of transcription on the –10/–35 class T7 A1 promoter and the sTap2+35-GGGA promoter (which has the same subset of promoter elements) depends on the presence of αCTDs, σ region 4, and β flap. The latter two RNAP elements are likely important for specific recognition of the –35 promoter element. (iii) Initiation from the sTap2 promoter also requires all three structural modules that were deleted in the mutant RNAPs. However, because this promoter lacks a functional –35 element, σ region 4 and the β flap are likely involved in nonspecific interactions with DNA located ∼35 base pairs upstream of the transcription start point (see “Discussion”). (iv) Initiation from the sTap2+35 promoter depends on σ region 4 but does not require αCTDs or the β flap domain. Thus, the –35 element, when present together with the –10 element and the GGGA element, allows transcription initiation in the absence of αCTDs and can be specifically recognized by σ region 4 even in the absence of the β flap.

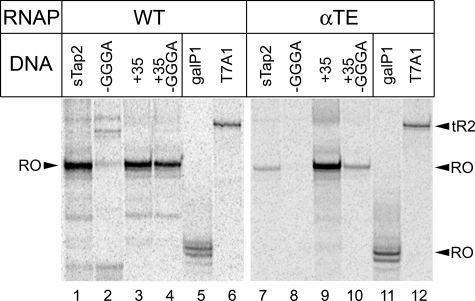

E. coli RNAP αCTDs Do Not Stimulate the Recognition of GGGA-containing Promoters by T. aquaticus RNAP—Specific requirement for αCTDs in transcription by T. aquaticus RNAP from the sTap2 promoter suggested that species-specific differences between T. aquaticus and E. coli RNAPs in the recognition of this promoter may be in part explained by differences in the properties of their αCTDs. To test this conjecture, we constructed a hybrid T. aquaticus core RNAP (αTE) in which αCTDs were substituted with corresponding domains from E. coli (E. coli α subunit amino acids 234–329 substituted for T. aquaticus amino acids 231–314). The hybrid RNAP also harbored deletion of the β′NCD that did not affect promoter recognition (see above). Control experiments demonstrated that the αTE RNAP did not differ from wild type T. aquaticus RNAP in recognition of the control T7 A1 and galP1 promoters (Fig. 5, compare lanes 5 and 6 and lanes 11 and 12, respectively). In contrast, the activity of this RNAP on the sTap2 promoter was reduced about 20-fold in comparison with the wild type RNAP (Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 7) and was comparable with the activity of the ΔαCTD RNAP on this promoter. The hybrid RNAP also possessed a much lower level of activity on the sTap2+35-GGGA promoter (Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 10). Thus, E. coli αCTDs can functionally compensate for T. aquaticus αCTDs during recognition of the T7 A1 promoter (as revealed by comparison of transcription by the ΔαCTD and αTE RNAPs) but cannot promote recognition of the GGGA-containing promoter sTap2.

FIGURE 5.

Recognition of the sTap2 promoter by T. aquaticus RNAP containing αCTDs from E. coli. Activities of wild type (WT) and mutant (αTE) RNAPs were measured on the sTap2, galP1, and T7 A1 promoters at 60 °C. Positions of the run-off transcripts (RO) generated from the sTap2 variants are indicated by arrowheads on both sides of the figure. The positions of the run-off and terminated (tR2) transcripts synthesized on the galP1 and T7 A1 templates, respectively, are shown on the right (the run-off transcript synthesized on T7 A1 is not shown on the figure).

Recognition of GGGA-containing Promoters by T. aquaticus RNAP Requires Contacts with Upstream DNA—E. coli RNAP αCTDs have been shown to stimulate transcription through direct interactions with DNA upstream of the –35 promoter element (see above). The dependence of T. aquaticus RNAP transcription from the sTap2 promoter on the presence of αCTDs suggests that T. aquaticus αCTDs also interact with upstream DNA to activate transcription. To directly test the role of upstream DNA sequences in transcription initiation from GGGA-containing promoters by T. aquaticus RNAP, we analyzed an sTap2 derivative that was truncated at position –37 relative to the starting point of transcription and thus lacked sequences upstream of the –35 element (sTap2-up) (Fig. 3A). The activity of wild type T. aquaticus RNAP on this promoter was dramatically reduced (about 10-fold) in comparison with the full-length sTap2 (Fig. 4). Remarkably, the low level of activity of RNAP with the deletion of αCTDs on sTap2-up was comparable with the activity of this mutant on the full-length sTap2 template.

It should be noted that the low level of transcription from sTap2-up by both wild type and ΔαCTD RNAPs strictly depended on the presence of the GGGA element, and an sTap2-up variant that lacked this element was essentially inactive with both RNAPs (less than 0.1% activity relative to wild type sTap2) (data not shown). To test whether other specific promoter motifs, in addition to the –10 and GGGA elements, could contribute to the sTap2-up recognition, we analyzed the role of the TG dinucleotide present upstream of the –10 element in the original sTap2 sequence (Fig. 3A). This motif is similar to the extended –10 promoter motif (see Introduction) but is not separated from the –10 element by an additional nucleotide. In agreement with published data (8), we found that replacement of TG in sTap2-up with AC did not affect promoter recognition by T. aquaticus RNAP (data not shown).

Thus, efficient initiation of transcription on the GGGA-containing promoter sTap2 by wild type T. aquaticus RNAP depends on: (i) specific RNAP interactions with the GGGA element and (ii) contacts with upstream DNA that apparently stimulate otherwise weak RNAP-promoter interactions.

DISCUSSION

Roles of Different Structural Modules of T. aquaticus RNAP in Recognition of GGGA-containing Promoters—Analysis of transcription from promoters containing the GGGA element by T. aquaticus RNAP mutants suggests that recognition of this type of promoter depends not only on specific contacts of σA region 1.2 with the GGGA element downstream of the –10 element but also on RNAP contacts with upstream DNA. Both αCTDs and σ region 4, whose deletions strongly impaired recognition of a GGGA-containing sTap-based promoter, likely directly interact with upstream DNA and stimulate RNAP-promoter interactions.

The role of αCTDs of T. aquaticus RNAP in promoter recognition is not well understood. It was shown that isolated αCTDs of T. thermophilus RNAP do not interact with UP element from the E. coli rrnB P1 promoter but can specifically recognize an upstream site in T. thermophilus 16 S rRNA promoter that bears no sequence resemblance to the E. coli UP element (21). Presently, no systematic analysis of upstream promoter sequences of T. aquaticus and related bacteria have been performed, and the specificity of DNA recognition by T. aquaticus αCTD remains unknown. Because the deletion of αCTDs impaired recognition of T7 A1 and sTap2 promoters, as well as other sTap-based promoters with varying upstream sequences,4 we propose that at least on these promoters, T. aquaticus αCTDs stimulate RNAP binding through favorable but sequence-nonspecific interactions with DNA. Nonspecific contacts of E. coli RNAP αCTDs with upstream DNA have been demonstrated to stimulate transcription from promoters that lack the UP element by increasing the rate of RNAP-promoter association (5, 6). Although the detailed kinetic mechanism of open complex formation by T. aquaticus RNAP remains to be determined, our data suggest that interactions of T. aquaticus αCTDs with upstream promoter DNA may play a similar role in promoter recognition and increase the rate of formation and/or isomerization of the closed promoter complex.

The role of nonspecific interactions of σ region 4 with DNA in promoter recognition has been discovered in the studies of recognition of the extended –10 galP1 promoter by E. coli RNAP (7). It has been shown that deletion of σ70 region 4, although not affecting RNAP activity on galP1 at 37 °C, impaired promoter opening at physiologically low temperature and, when combined with deletion of αCTDs, disrupted promoter binding at all temperatures (7). We found that, similarly to what has been observed for E. coli RNAP, deletion of σA region 4 did not affect galP1 transcription by T. aquaticus RNAP at high temperature, thus demonstrating that at these conditions contacts of σ region 4 with the –35 promoter region are not required for recognition of extended –10 promoters by T. aquaticus RNAP. In contrast, σA region 4 was required for efficient transcription from GGGA-containing promoters, even in the absence of the –35 element. Thus, nonspecific contacts of σ region 4 with DNA play an essential role in recognition of promoters of this type by T. aquaticus RNAP.

The β flap domain, whose deletion also disrupted recognition of GGGA-containing promoters, is unlikely to directly interact with promoter DNA based on structural considerations (20, 22). Because this domain has been shown to play a role in proper positioning of σ region 4 in the holoenzyme (16), we propose that it acts indirectly by facilitating nonspecific contacts of σ region 4 with DNA ∼35 bp upstream of the transcription start. Deletion of the β flap also affected recognition of –10/–35-type promoters T7 A1 and sTap2+35-GGGA, apparently by disrupting specific contacts of σ region 4 with the –35 element. Surprisingly, however, T. aquaticus RNAP lacking the β flap could still recognize the sTap2+35 promoter, and the recognition was dependent on the presence σ region 4 and the functional –35 element. Thus, in the presence of the GGGA element, T. aquaticus σA region 4 can interact with the –35 element even in the absence of the β flap. It remains to be seen how the proper positioning of σA region 4, which is presumably required for interactions with the –35 consensus element, is achieved in this case.

In summary, analysis of promoter recognition by T. aquaticus RNAP and its mutant variants reveals three types of promoters that differ in their sensitivity to specific RNAP mutations and are apparently recognized through different mechanisms: (i) classical –10/–35 promoters, (ii) extended –10 promoters, and (iii) GGGA-containing promoters with or without the –35 element. Comparison of these promoters allows one to assess the relative contribution of specific and nonspecific RNAP contacts with DNA in recognition of different types of promoters. Nonspecific RNAP-DNA contacts play a more essential role in transcription from promoters that contain the –10 basal promoter element in combination with either GGGA (as in sTap2) or –35 (as in T7 A1 or sTap2+35-GGGA) elements, whereas the presence of both –35 and GGGA elements (in sTap2+35) or TG element (in galP1) allows promoter recognition even in the absence of nonspecific RNAP contacts with upstream DNA.

The difference in the nature of nonspecific contacts with upstream DNA may be one of the main reasons for the different specificities exhibited by T. aquaticus and E. coli RNAPs on GGGA-containing promoters. Previously, it was demonstrated that contacts of E. coli RNAP with upstream DNA and the –35 element jointly stabilize initial binding of RNAP to a promoter (23). We found that E. coli αCTDs cannot functionally substitute for T. aquaticus αCTDs during the recognition of sTap-based promoters. Thus, the ability of T. aquaticus RNAP to transcribe from GGGA-containing promoters in the absence of the –35 element may be explained by stronger nonspecific contacts of its αCTDs with upstream DNA (as compared with the E. coli RNAP) that compensate for the absence of contacts with the –35 element. Furthermore, it has been shown that substitutions that affected contacts between proximally located αCTD and σ region 4 in E. coli RNAP decreased activation of transcription by the UP element (24). Thus, specific changes present at the αCTD-σ interface in T. aquaticus RNAP may also stimulate transcription from GGGA-containing promoters by mediating more efficient transcription activation by upstream DNA.

It should be noted that additional T. aquaticus RNAP elements, together with σ regions 1.2 and 4, and αCTDs may also contribute to the recognition of GGGA-containing promoters because all mutant variants of T. aquaticus RNAP that we analyzed were still able to specifically initiate transcription on the sTap2 promoter, although with a significantly reduced activity. Identification of additional RNAP determinants that may be involved in the recognition of various types of promoters is an important goal of future studies.

Recognition of the GGGA Element by E. coli RNAP—We found that the specificity of recognition of promoter region downstream of the –10 element by the E. coli σ70 subunit does not differ from that of the T. aquaticus σA subunit. At the same time, in contrast to T. aquaticus RNAP, E. coli RNAP holoenzyme is unable to initiate transcription on GGGA-containing promoters in the absence of the –35 element, thus revealing an important role for the core enzyme in promoter recognition (see previous section). Differences in promoter utilization between RNAPs from Bacillus subtilis, Rickettsia prowazekii, and E. coli were also reported to be determined by the core enzyme of RNAP (25, 26). Thus, the contribution of bacterial RNAP core to species specificity of promoter recognition may be more significant than previously thought.

When present in promoters containing the –35 element, the GGGA element stimulates transcription by E. coli RNAP holoenzyme. This is in agreement with the data of Haugen et al. (9, 11), who showed that the E. coli RNAP holoenzyme can specifically interact with the nontemplate DNA strand downstream of the –10 element, in a region corresponding to the GGGA element. Mutational and cross-linking analysis identified two candidate residues from E. coli σ70 region 1.2, Met102 and Tyr101, that most likely participate in interactions with this region (11). In particular, residue Met102 was proposed to directly interact with the nucleotide 2 base pairs downstream of the –10 element. Interestingly, T. aquaticus σA contains a leucine instead of methionine at the corresponding position in region 1.2. This may indicate that (i) this substitution does not disrupt specific σ-DNA contacts (in contrast to a more dramatic M102A substitution analyzed by Haugen et al. (11)) or (ii) this residue does not directly interact with DNA but may be important for maintaining a specific conformation of σ required for DNA binding. Further structural analyses of interactions of σ region 1.2 with DNA are needed to establish the detailed molecular mechanism of the recognition of this promoter element by RNAP.

Substitutions in the discriminator region in the rrnB P1 promoter (in particular, a C to G substitution at position corresponding to the second G in the GGGA element) greatly stabilized complexes formed by E. coli RNAP (9, 11). In agreement with this, we found that the GGGA element dramatically increased stability of E. coli RNAP complexes on synthetic promoters based on the sTap aptamers specific to T. aquaticus σA subunit. Remarkably, this element had a similar effect on the promoter complex stability of T. aquaticus RNAP (8) and hampered promoter escape by RNAPs from both E. coli and T. aquaticus, indicating that it plays similar roles during transcription by both RNAPs. This suggests that the GGGA-like motifs may stimulate specific RNAP-promoter interactions and stabilize promoter complexes in other bacteria and, depending on the properties of the RNAP core enzyme and the presence of additional promoter elements, determine species-specific differences in promoter utilization.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Nechaev for reading the manuscript and for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM RO1 GM64530 (to K. S.). This work was also supported in part by Russian Foundation for Basic Research Grant 07-04-00247, Russian Academy of Sciences Presidium Program in Molecular and Cellular Biology grants (to K. S. and A. K.), and President of Russian Federation Grant MK-1017.2007.4. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: RNAP, RNA polymerase; αCTD, C-terminal domain of the RNAP α subunit; NCD, nonconserved domain.

A. Kulbachinskiy, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Gross, C. A., Chan, C., Dombroski, A., Gruber, T., Sharp, M., Tupy, J., and Young, B. (1998) Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 63 141–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barne, K. A., Bown, J. A., Busby, S. J., and Minchin, S. D. (1997) EMBO J. 16 4034–4040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross, W., Gosink, K. K., Salomon, J., Igarashi, K., Zou, C., Ishihama, A., Severinov, K., and Gourse, R. L. (1993) Science 262 1407–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang, Y., Murakami, K., Ishihama, A., and deHaseth, P. L. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178 6945–6951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis, C. A., Capp, M. W., Record, M. T., Jr., and Saecker, R. M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 285–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross, W., and Gourse, R. L. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 291–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minakhin, L., and Severinov, K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 29710–29718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feklistov, A., Barinova, N., Sevostyanova, A., Heyduk, E., Bass, I., Vvedenskaya, I., Kuznedelov, K., Merkiene, E., Stavrovskaya, E., Klimasauskas, S., Nikiforov, V., Heyduk, T., Severinov, K., and Kulbachinskiy, A. (2006) Mol. Cell 23 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haugen, S. P., Berkmen, M. B., Ross, W., Gaal, T., Ward, C., and Gourse, R. L. (2006) Cell 125 1069–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travers, A. A. (1980) J. Bacteriol. 141 973–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haugen, S. P., Ross, W., Manrique, M., and Gourse, R. L. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 3292–3297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulbachinskiy, A., Bass, I., Bogdanova, E., Goldfarb, A., and Nikiforov, V. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186 7818–7820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuznedelov, K., Minakhin, L., and Severinov, K. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 370 94–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuznedelov, K., Lamour, V., Patikoglou, G., Chlenov, M., Darst, S. A., and Severinov, K. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 359 110–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuznedelov, K. D., Komissarova, N. V., and Severinov, K. V. (2006) Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 410 263–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuznedelov, K., Minakhin, L., Niedziela-Majka, A., Dove, S. L., Rogulja, D., Nickels, B. E., Hochschild, A., Heyduk, T., and Severinov, K. (2002) Science 295 855–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minakhin, L., Nechaev, S., Campbell, E. A., and Severinov, K. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183 71–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nudler, E., Kashlev, M., Nikiforov, V., and Goldfarb, A. (1995) Cell 81 351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson, K. S., and von Hippel, P. H. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 244 36–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vassylyev, D. G., Sekine, S., Laptenko, O., Lee, J., Vassylyeva, M. N., Borukhov, S., and Yokoyama, S. (2002) Nature 417 712–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada, T., Yamazaki, T., and Kyogoku, Y. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 16057–16063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami, K. S., Masuda, S., Campbell, E. A., Muzzin, O., and Darst, S. A. (2002) Science 296 1285–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sclavi, B., Zaychikov, E., Rogozina, A., Walther, F., Buckle, M., and Heumann, H. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 4706–4711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross, W., Schneider, D. A., Paul, B. J., Mertens, A., and Gourse, R. L. (2003) Genes Dev. 17 1293–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aniskovitch, L. P., and Winkler, H. H. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177 6301–6303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Artsimovitch, I., Svetlov, V., Anthony, L., Burgess, R. R., and Landick, R. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182 6027–6035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]