Abstract

Richard von Volkmann (1830–1889), one of the most important surgeons of the 19th century, is regarded as one of the fathers of orthopaedic surgery. He was a contemporary of Langenbeck, Esmarch, Lister, Billroth, Kocher, and Trendelenburg. He was head of the Department of Surgery at the University of Halle, Germany (1867–1889). His popularity attracted doctors and patients from all over the world. He was the lead physician for the German military during two wars. From this experience, he compared the mortality of civilian and war injuries and investigated the general poor hygienic conditions in civilian hospitals. This led him to introduce the “antiseptic technique” to Germany that was developed by Lister. His powers of observation and creativity led him to findings and achievements that to this day bear his name: Volkmann’s contracture and the Hueter-Volkmann law. Additionally, he was a gifted writer; he published not only scientific literature but also books of children’s fairy tales and poems under the pen name of Richard Leander, assuring him a permanent place in the world of literature as well as orthopaedics.

Introduction

“He walked towards us, tall and lean, with a mighty red beard, wearing tartan colored pants, a colorful embroidered waistcoat and a flying red tie—the kind an artist would wear…” [12–14].

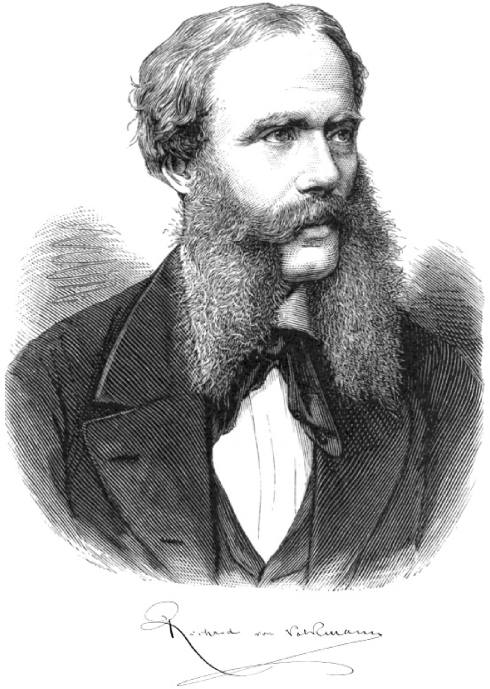

Richard von Volkmann (1830–1889) was one of the founders of the German Society of Surgeons and one of the most famous surgeons of the 19th century. Terms such as Volkmann’s contracture and the Hueter-Volkmann law have immortalized his name (Table 1). Daring to paint his portrait with only a few words, we would describe him as extremely passionate about his work, filled with energy, self-confident, striving indefatigably for knowledge, and intolerant of his own mistakes and those of colleagues in surgical and scientific matters. His way of thinking was greatly influenced by the classic humanitarian school and his patients were always at the center of his attention. We attempt to provide insight into the thoughts and feelings of a person who lived 130 years ago (Figs. 1, 2).

Table 1.

Accomplishments of Richard von Volkmann that bear his name

| Accomplishment | Description |

|---|---|

| Volkmann’s ischemic contracture | Ischemic muscle contracture (flexion contracture) attributable to external pressure causing irreversible necrosis of muscle tissue, usually seen in the hand, resulting in claw hand, and most frequently observed in children |

| Volkmann’s triangle | Avulsed posterior edge of the tibia in ankle fractures |

| Hueter-Volkmann law | Orthopaedic concept describing growth of immature bones |

| Volkmann’s splint | Splint used for a fracture of the lower extremity, consisting of a footpiece and two lateral supports |

| Volkmann’s syndrome I (or Volkmann’s disease) | Congenital talus luxation. Eponym used to indicate tibiotarsal dislocation causing a congenital deformity of the foot. |

| Volkmann’s bench | For application of plaster of Paris cast |

| Volkmann’s abscess | From tuberculosis of the cervical vertebra |

| Volkmann’s spoon | Used in performing curettage of the above-named abscess |

Fig. 1.

Richard von Volkmann (1830–1889).

Fig. 2.

This is a monument of Richard von Volkmann in front of the old Surgical University Clinic at Halle an der Saale (Germany) in 2002 (today the Clinic of Urology).

Early in his career, Volkmann earned himself a legendary name, and in the later years, the rich and famous would become his patients. His love of surgery dictated the relationships with his colleagues and his behavior with them. His knowledge and abilities, paired with his charming personality, made him many friends. These friends sometimes were confronted with the contrary parts of his personality. As was stated in an obituary, “…von Volkmann was in all terms an eccentric person. He was not an everyday person. Everyone who met him, even if only for a short moment, knew that straight away. There were surely only a few friendships that went on without any thundering, but those friends he made were to a great portion, even in those moments, so fascinated by his personality, that these moments had no effect on the friendship” [2, 4, 6, 7, 9].

Friedrich von Trendelenburg said, “…He [Volkmann] was…picturesque in speech and always ready to intervene in a debate. Even when listening he was full of emotions and life that would show in his face. Being slim and ‘elastic,’ he looked more like an artist than a doctor in his velvet coat with a big colorful tie” [16]. His temper caused him problems as seen through his friendship with Theodore Billroth. Their friendship lasted 20 years but ended one day because of a scientific dispute about the source and the therapy of wound infections. Volkmann was quoted as saying, “People easy accept the superior and even the inferior, but not the different one. I have often experienced this in my life.” Volkmann was an exact and ingenious surgeon; a sympathetic, understanding doctor; a successful scientist with sharp analytic capabilities; a didactically talented teacher; and an artist and poet. His collection of simple stories and poems (Dreams at French Firesides [10]) makes us smile and confirms he was open to the gentle moments in life, full of spirit and soul.

Chronology of His Life

Early Years

The second child of 12, Richard von Volkmann was born on August 17, 1830, in Leipzig. His father, Dr. Alfred Volkmann (1801–1877), University Professor of Physiology and Anatomy at Halle, was a noted university lecturer of experimental physiology and described the transverse canals (Volkmann’s canals) in the Haversian system of bones.

His mother, Adele, was the daughter of Gottfried Christoph Härtel, the owner of a book and music instrument shop and co-owner of the publishing house, Breitkopf and Härtel [4, 12–14]. (This company, renowned for publishing musical scores, would later publish Volkmann’s journal.) The education of young Richard began at home by a house-teacher. At 13 years of age, he attended the Grand-Ducal School in Grimma for 6 years. Although he was interested in the old languages, he obeyed his father’s wishes and began studying medicine. He studied in Gießen, Halle, possibly Heidelberg, and finished his studies in Berlin. His medical school was at Halle, with graduation in August 1854. His interest in surgery was awoken through his friendship with Theodore Billroth and under the guidance of Bernhard von Langenbeck, who at that time was the most famous surgeon in Germany.

The Young Physician Scientist

In the summer of 1855, Volkmann became the “Medicus secundarius” of the surgical clinic led by Professor Blasius. Because of the latter’s eyesight problems, Volkmann became the clinic leader and chief surgeon. He left this surgery clinic and began a private practice as a general practitioner in Halle (1857–1867). Although he was not initially on the teaching staff at the university, with some help from his father, he began lecturing pro bono. He gave his students fascinating insights into the world of microscopy and stunned them with didactic skills and passionate excursions. The students loved and adored him.

Volkmann also had a very good reputation for hard work as a general practitioner. With indefatigable energy, he served his patients during the day, pursued scientific studies, and prepared his readings in pathologic anatomy for the university. From this time, there is one saying of his that is often quoted, “…either a doctor has no bread or he has no time to eat it” [14]. However, he did manage to find time to marry. On May 28, 1858, he married Anna von Schlechtendahl, daughter of the Professor of Botany and Head of the Botanical Gardens at Halle. They would have 11 children together.

In 1862, the young 32-year-old surgeon published his thoughts about the growth of immature bones [19]. Volkmann observed “the child’s skull grows in such a way that the bones are never overstressed, … the periosteum places new bone layer by layer, while on the inside increasing pressure pushes away the old bone which atrophies …” He also “suggested alterations in the growth of long bones as a result of tension and compression on the epiphyseal plate.” That same year, Carl Hueter (1838–1882) while in Paris described the remodeling of bone in the ankle and subtalar joints of infants and adults [5]. He noted “the changes of the joint surfaces are preferentially cause by relatively greater growth of the bony parts which are relatively less pressure.” Later Volkmann would create a link between his theories [19, 21, 24] and the studies of Hueter, leading to an orthopaedic concept, the so-called Hueter-Volkmann law [11]. In 1949, Blount and Clarke [3], in their discussion of epiphyseal stapling, referred to the works of Hueter and Volkmann from 1862. The first English language reference that specifically uses the term Hueter-Volkmann law was Arkin and Katz’s 1956 article in TheJournal of Bone and Joint Surgery [1].

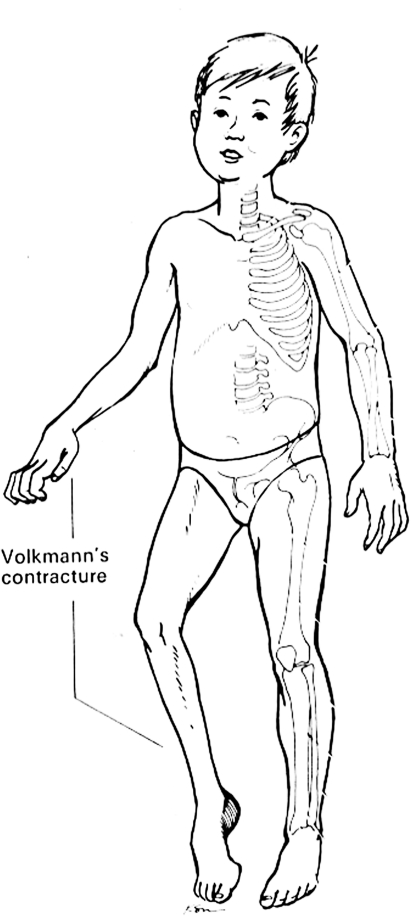

Around 1864, Theodore Billroth (1829–1894) and Franz Baron von Pitha (1810–1875) requested he write a chapter entitled, “Dysfunctions of the musculoskeletal system” for their Handbook of Basic and Special Surgery. Volkmann wrote 700 pages, his own textbook, within the handbook [25]. Published initially in 1865 (second edition in 1872), it quickly became the most popular surgical textbook of its time. In one chapter, he described, for the first time, his ischemic muscle contracture: “the severe contractions, after applying too tight of a bandage on the forearm for a fracture, are at least partially due to infectious muscle contraction and not all cause pressure induced primary nerve lesions” [25, 39]. (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Volkmann ischemic contracture of the forearm and leg is shown. In 1881, von Volkmann wrote about the etiology of this contracture: “For years I have called attention to the fact that the pareses and contractures of limbs following application of tight bandages are caused not by pressure paralysis of nerves, as formerly assumed, but by the rapid and massive deterioration of contractile substance and by…reactive and regenerative processes” [39]. (Reproduced with permission and copyright © 1979 of The British Bone and Joint Society from Mubarak SJ, Carroll NC. Volkmann’s contracture in children: aetiology and prevention.J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61:285–293.)

The War Years

As a civilian and freelance surgeon, Volkmann took charge of the military field hospital during the Prussian-Austrian war in 1866. (The war resulted in Prussian control over all modern German states.) Because of his war efforts in March 1867 at age 36, he was appointed a Professor of Surgery at the University of Halle (Fig. 2).

In April 1870, in cooperation with many colleagues from Germany, he founded Volkmann’s Collection of Clinical Reports. This journal covered the most important aspects of medicine of the time and made the name Richard von Volkmann famous. (Three hundred sixty-two issues were published until his death.)

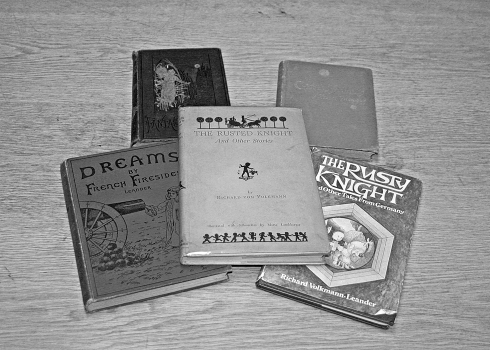

In August 1870, he again was given leave to join the armed forces for the Franco-Prussian War. He assumed the rank of Surgeon General for the war. Volkmann was responsible for all 12 army hospitals and 1442 beds. During the 4-month siege of Paris, Volkmann found time to write his Dreams at French Firesides [10], which he sent home to his family. These fairy tales were edited under his pen name Richard Leander. This fairy tale collection appeared in more than 300 editions, with more than one million copies sold (Fig. 4). One poem, “Memory,” was set to music by Gustav Mahler, the famous Austrian composer (1860–1911), for his song “Songs from the Youth” (“Lieder und Gesänge: Aus der Jugendzeit”).

Fig. 4.

English editions of Volkmann’s book Dreams at French Firesides [10] were published in 1873, 1887, 1890, 1933, and 1974.

After the war when he returned to his own hospital, he found catastrophic numbers of infectious diseases spreading throughout the ward. Later he wrote, “The mortality after large amputations and complicated fractures grew year by year. In the summer of 1871, during my absence on the battlefield, the clinic was crowded by a large amount of injured. For eight months, in the winter 1871 to 1872, the numbers of blood poisoning and rose disease victims were so great, that I considered applying for a temporary closure of the facility. Without a morgue, the dead stayed in the cellar beneath the wards until the funeral, even in the summer” [14, 31].

The Years of Leadership

In 1872, Bernhard von Langenbeck (1810–1887, Berlin), Gustav Simon (1824–1876, Heidelberg), and Richard von Volkmann (Halle) founded the German Society of Surgeons. Volkmann was the secretary of the society for 14 years and president from 1886 to 1887. Volkmann’s paper “Comparing Mortality Statistics of Analogous War and Peace Injuries” headed the first conference with the subject. During the presentation, he explained how gunshot fractures had a lower mortality (24%) than open leg fractures in civilians (39%) [31]. His interest in these results led him to Lister’s work in England.

Joseph Lister (1827–1912) developed his “antiseptic system of treatment” in 1867 as a prophylactic method to prevent wound infections. Volkmann sent his assistant, Max Schede, to Lister’s clinic, and soon after his return, Volkmann began using Lister’s method (Fig. 5). On February 16, 1873, he wrote to Billroth: “…since autumn of last year (1872), I have been experimenting with Lister’s method…. Already, the first trials in the old ‘contaminated’ house, show wounds healing, uneventful, without fever and pus.”

Fig. 5.

Joseph Lister (center) supervises the use of the carbolic acid spray during one of his first antiseptic operations, circa 1865 (©Bettmann/CORBIS). In Germany, the method of the Lister antisepsis was introduced by Richard von Volkmann, Carl Thiersch, and Adolf Bardeleben in 1872.

During the Third Congress of the Surgeon’s Society in April 1874, Volkmann was the first to present a lecture about “the antiseptic occlusive-bandage and its influence towards the healing process of the wounds” [33]. Volkmann’s presentation became famous. Bergmann years later remarked (1890) about this presentation, “It was at this point, during our Third Congress, that von Volkmann mentioned for the first time, the influence of Lister’s method on the wound-healing process. His report had effects all over the country and caused emotions ranging from enthusiastic applause to critical opposition. As well, it led to the fact that the method was established faster in Germany than in any other developed country” [2]. Lister agreed as he wrote the preface to one of Volkmann’s papers, “he [Volkmann] appreciating the paramount importance of the antiseptic principle, carries it out with an intelligent care such as can alone ensure success” [9, 14, 15, 33].

The new closed therapy of wounds had many advantages compared with open treatment. The skin of the patient, the surgeon’s hands, all instruments, and all bandages were disinfected with 5% carbolic acid. A 2% solution of carbolic acid was used continuously during the procedure. Volkmann used 3- to 4-cm drains for all wounds. In most cases, the wounds were not closed. Changing the bandages was always performed using carbolic acid sprayers. The treatment of open fractures especially benefited from this new method. Volkmann reported, “Until a few years ago, open fractures were potentially deadly injuries. Acute septicemia and pyremia killed a majority of the patients, especially in hospitals. France and Germany suffered immensely due to this problem. Even in the simplest case of an open fracture, when a bone particle would spear the skin during the injury and then go back in place or reposition, no surgeon could say if the patient would survive” [14].

In 1877 and 1878, he twice received large pay increases to remain at Halle. The Minister justified this increase in salary with the following words: “Professor Volkmann is undoubtedly one of our supreme surgeons and the introduction of Lister’s method is mainly his credit. For this reason, he already earns a great deal of the enormous evolution that surgery has made in recent years. Also, he is a gifted lecturer who fascinates and ties his listeners with his personal liveliness” [14].

In 1878, he described the first-mentioned transsacral extirpation of the rectum [36]. In 1880, he became editor of the Zentralblatt für Chirurgie with F. Koenig (Göttingen) and E. Richter (Breslau).

He participated in the International Medical Congress in London (1881) with his keynote presentation entitled “The Modern Surgery” [40]:“…through systematical procedures we are able to stop the foul work of these microorganisms. Instead of fortune and misfortune, that used to be a big part of the daily routine of a surgeon, now knowledge and ignorance, personal capability and non-capability, precision and carelessness are the factors that matter….” “In this modernized surgery we can now perform elective surgery on the joints, the bones and internal organs without fearing the sure death of the patient…. Also now we have to take responsibility for the outcome of the operation and the further development of the sickness.” He chose words that are more accurate today than they ever were, “…not long ago, after ending a bloody operation, the surgeon was in the same situation as a farmer after cultivating his fields. He had to live with whatever occurred and was powerless toward the elements that could bring him rain and sunshine or storm and hail. Today the surgeon is a manufacturer from whom good articles are expected…” [14]. This was a radical change in the approach to surgery, which until this point was a treatment of last resort because of the high likelihood of infection.

As a result of his poor health, he declined succeeding von Langenbeck in Berlin. Later, in 1882, he was made an honorary citizen of Halle. His international reputation was flourishing as one of the leading physicians in Europe. Even Pope Pius IX consulted him for a foot ailment in 1885.

In November 28, 1889, Richard von Volkmann died at 59 years of age in the Neurologic Clinic of Professor Binswanger in Jena [8, 9]. He had suffered for almost 20 years from a painful spinal cord malady, which, to this day, cannot be clearly identified. Although suffering from this and paralysis of his limbs and surviving on a liquid diet, he tried to face all his duties. His stern self-discipline was evident even on his deathbed when his colleagues met at his home to plan the next conference.

Major Scientific Contributions

His push for sterility in the operating room following Lister’s principles advanced surgery as a specialty [33, 40]. Furthermore, Volkmann’s powers of observation and creativity, as a seasoned practitioner, led him to important accomplishments that to this day bear his name. Volkmann was one of the first to publish clinical case histories. He was certainly one of the fathers of orthopaedic surgery, with many important papers on limb growth [19–21, 24, 29], surgery for muscular torticollis [41], hypertrophy of capital femoral epiphysis [28], a goniometer [22], ischemic limb contracture [25, 39], knee and hip osteotomies [34, 38], penetrating injuries of the knee [18], loss of motion of the forearm [26], Esmarch’s bloodless hip surgery [32], treatment of septic bone and joints [20, 37], great toe exostosis [17], gunshot injuries [27, 31], bone and joint resection for neoplasm [30, 35], and the etiology and treatment of congenital clubfeet [23]. He recommended simple Achilles tenotomy and casting and to try at all costs to avoid major operations on the foot. Today, his name is immortalized by Volkmann’s contracture and Hueter-Volkmann law (Table 1).

Discussion

Volkmann’s personality and leadership led to the development of the German Society of Surgeons and the journal Collection of Clinical Reports. His evidence-based medicine study “Comparing Mortality Statistics of Analogous War and Peace Injuries” led to operating room sterility 130 years before it became popular. His efforts, science, and leadership led antiseptic principles in German operating rooms before Lister was able to accomplish the same in Britain [8, 11, 33]. His many papers on orthopaedic topics, especially treatment of gunshot wounds and open fractures, certainly justify considering him one of our orthopaedic fathers. Volkmann was truly a remarkable individual who has left his mark and name in medicine as well as literature.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this manuscript to the memory of Col Prof Dr Heinz Gerngross (1947–2005), former head of the Department of Surgery (1993–2005), Military Hospital of Ulm, Ulm, Germany.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Arkin AM, Katz JF. The effects of pressure on epiphyseal growth; the mechanism of plasticity of growing bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1956;38:1056–1076. [PubMed]

- 2.Bergmann E. Nekrolog: Richard von Volkmann [Necrology: Richard von Volkmann]. In: Verhandlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Chirurgie. Neunzehnter Kongress. Berlin, Germany: Hirschwald; 1890:3–6.

- 3.Blount WP, Clarke GR. Control of bone growth by epiphyseal stapling. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1949;31:464–478. [PubMed]

- 4.Braun H. Zur Erinnerung an den 100. Geburtstag (17 August 1830) Richard von Volkmann’s [In memoriam to the 100th birthday (17 August 1830) of Richard von Volkmann]. Zentralbl Chir. 1930;57:2033–2037.

- 5.Hueter C. Anatomische Studien an den Extremitätengelenken Neugeborener und Erwachsener [Anatomic studies on the joints of the extremities in newborns and adults]. Virchow Arch. 1862;26:484–519.

- 6.König F, Richter E. Richard von Volkmann. Zentralbl Chir. 1889;51:1–6. 5.

- 7.Kraske F. Richard von Volkmann: ein Nekrolog [Richard von Volkmann: a necrology]. Münchner Med Wschr. 1890;77:9–11.

- 8.Krause F. Zur Erinnerung an Richard von Volkmann [To the memoriam of Richard von Volkmann]. Berlin Klin Wschr. 1889;26:1098.

- 9.Krause F. Richard von Volkmann. Zur 40. Wiederkehr seines Geburtstages [Richard von Volkmann: to the 40th recurrence of his birthday]. Chirurg. 1929;1:625–631.

- 10.Leander R. Träumereien an französischen Kaminen: Märchen [Dreams at French Firesides]. Leipzig, Germany; Verlag Breitkopf und Härtel; 1871.

- 11.Mehlman CT, Araghi A, Roy DR. Hyphenated history: the Hueter-Volkmann law. Am J Orthop. 1997;26:798–800. [PubMed]

- 12.Schober KL. Our surgical heritage: Richard von Volkmann on the 150th anniversary of his birth on 17 August 1830. Zentralbl Chir. 1980;105:1635–1643. [PubMed]

- 13.Schober KL. Memorial presentation on the 150th birthday of Richard von Volkmann, the co-founder of the German Society of Surgery. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1981;255:597–606. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Schober KL. Reflections on the 100th anniversary of the death of Richard von Volkmann in November 1989. Chirurg. 1990;61:338–340. [PubMed]

- 15.Thorwald J. Das Jahrhundert der Chirurgen [The Century of the Surgeons]. Stuttgart, Germany: Steingrüben Verlag; 1956.

- 16.Trendelenburg F. Die ersten 25 Jahre der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Chirurgie: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Chirurgie [The First 25 Years of the German Society of Surgery: A Contribution to the History of Surgery]. Berlin, Germany: Verlag Julius Springer; 1923.

- 17.Volkmann R. Über die sogenannte Exostose der großen Zehe [About the so-called exostosis of the big toe]. Virchows Archiv. 1856;10:297–306.

- 18.Volkmann R. Penetrierende Kniegelenkswunde, zweimalige Gelenkspunktion, Heilung ohne Ankylose [Penetrating knee joint wound, healing without ankylosis following twice repeated puncture]. Deutsche Klinik. 1861;13:411.

- 19.Volkmann R. Chirurgische Erfahrungen über Knochenverbiegung und Knochenwachstum [Surgical experiences about bone deformities and bone growth]. Virchows Archiv. 1862;24:512–540.

- 20.Volkmann R. Über die katarrhalischen Formen der Gelenkeiterung [About the “catarrhal inflammation” type of septic joints]. Arch Klin Chir. 1862;408–447.

- 21.Volkmann R. Über massenhafte Neubildung Havers’scher Kanälchen im harten Knochengewebe in einem Falle sogenannter entzündlicher Osteoporose [About the massive regeneration of the Haversian system in the hard bone tissue in one case of so-called inflammatory osteoporosis]. Deutsche Klinik. 1862;14:426.

- 22.Volkmann R. Ein Winkelmaß für das Hüftgelenk (Coxankylometer) [A goniometer for the hip joint]. Arch Klin Chir. 1862;2:294–299.

- 23.Volkmann R. Zur Ätiologie der Klumpfüsse [Etiology of the equinovarus]. Deutsche Klinik. 1863;15:329.

- 24.Volkmann R. Die Frage nach der Persistenz und Dauerhaftigkeit der mit Hilfe der periostalen Osteoplastik gewonnenen neugebildeten Knocheneinlagen [The question about persistency and permanence of the new bone growth bone after periosteal osteoplasty]. Deutsche Klinik. 1863;15:204.

- 25.Volkmann R. Die Krankheiten der Bewegungsorgane [Diseases of the musculoskeletal system]. In: von Pitha FR, Billroth T, eds. Handbuch der allgemeinen und speziellen Chirurgie. Zweiter Band, zweite Abteilung, erste Hälfte. Stuttgart, Germany: Ferdinand Enke; 1865:234–920.

- 26.Volkmann R. Über den Verlust der Pronations- und Supinationsbewegungen nach Brüchen am Vorderarm [About the loss of pronation and supination capability after forearm fractures]. Berl Klin Wschr. 1867;5:193.

- 27.Volkmann R. Einige Fälle von geheilter penetrierender Schusswunde des Abdomens und besonders der Leber; aus dem Feldzuge 1866 [Some cases of healed penetrating gunshot wounds to the abdomen, especially to the liver (war 1866)]. Deutsche Klinik. 1867;20:3.

- 28.Volkmann R. Die Hypertrophie des Schenkelkopfes in Folge lokal gesteigerter Ernährung [The hypertrophy of the caput femoris following increased nutrition]. Berl Klin Wschr. 1868;5:204.

- 29.Volkmann R. Beiträge zur Anatomie und Chirurgie der Geschwülste [Contributions to the anatomy and surgery of growth]. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1873;15:556–561.

- 30.Volkmann R. Zwei Fälle von Gelenkresektionen wegen Neoplasma [Two cases of joint resections due to a neoplasm]. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1873;15:562–567.

- 31.Volkmann R. Zur vergleichenden Mortalitätsstatistik analoger Kriegs- und Friedensverletzungen [Comparing mortality statistics of analogous war and peace injuries]. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1873;15:1.

- 32.Volkmann R. Über die Anwendung der Esmarch’schen blutsparenden Verfahrens bei Exartikulation des Hüftgelenkes [About the application of the Esmarch’s blood saving technique for the exarticulation of the hip joint]. Zentralbl Chir. 1874;1:65–66.

- 33.Volkmann R. Über den antiseptischen Okklusivverband und seinen Einfluss auf den Heilungsprozess der Wunden [About antiseptic occlusive bandages and their influence on the healing process of wounds]. Volkmanns Sammlung klinischer Vorträge II Serie. 1875;96:759–812.

- 34.Volkmann R. On two cases of ankylosis of the knee joint treated by osteotomy. Edinburgh Med J. 1875;20:794–799. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Volkmann R. Resektion eines erheblichen Teiles des Kreuzbeins durch dessen ganzen Dicke hindurch und mit Eröffnung des Rückenmarkkanals wegen eines zentralen Knochensarkoms [Resection of the largest part of the sacrum, opening of the spinal canal due to a central sarcoma of the bone]. Verh 6 Kongr Dtsch Ges Chir. 1876;I:82.

- 36.Volkmann R. Über den Mastdarmkrebs und die Exstirpatio recti [On rectal cancer and the exstirpatio recti]. Volkmanns Sammlung klinischer Vorträge III Serie. 1878;131:1113–1128.

- 37.Volkmann R. Die perforierende Tuberkulose der Knochen des Schädeldaches [Perforating tuberculosis of the skull bones]. Zentralbl Chir. 1880;7:3–7.

- 38.Volkmann R. Osteotomia subtrochanterica und Meisselresektion des Hüftgelenks [Subtrochanteric osteotomy and chisel resection of the hip joint]. Zentralbl Chir. 1880;7:65–69.

- 39.Volkmann R. Ischämische Muskellähmungen und -kontrakturen [Ischemic muscle paralysis and contractures]. Zentralbl Chir. 1881;8:801–803.

- 40.Volkmann R. Die moderne Chirurgie: Vortrag vom “Internationalen Medizinischen Kongress” am 8 August 1881 in London [The Modern Surgery: Invited Lecture at the International Congress of Medicine in London]. Leipzig, Germany: Verlag Breitkopf und Härtel; 1882.

- 41.Volkmann R. Das sogenannte angeborene Caput obstipum und die offene Durchschneidung des Musculus sternocleidomastoideus [The so-called connatal caput obstipum and the open transection of the musculus sternocleidomastoideus]. Zentralbl Chir. 1885;12:233–237.