Abstract

Purpose

Invisible near-infrared (NIR) light is safe and penetrates relatively deeply through tissue and blood without altering the surgical field. Our hypothesis is that NIR fluorescence imaging will enable visualization of ureteral anatomy and flow, intraoperatively and in real-time.

Materials and Methods

The carboxylic acid form of NIR fluorophore IRDye™800CW (CW800-CA) was injected intravenously and its renal clearance kinetics and imaging performance quantified in 350 g rats and 35 kg pigs. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and electrospray-time of flight (ES-TOF) mass spectrometry were used to characterize CW800-CA metabolism in the urine. The clinically available NIR fluorophore ICG was also used via retrograde injection into the ureter. Using both NIR fluorophores, ureters were imaged under conditions of steady state, intraluminal foreign bodies, and injury.

Results

In rat models, the highest signal-to-background ratio (SBR) for visualization occurred after intravenous (IV) injection of 7.5 μg/kg CW800-CA, with values of ≥ 4.0 and ≥ 2.3 at 10 min and 30 min, respectively. In pig models, 7.5 μg/kg CW800-CA clearly visualized normal ureter and intraluminal foreign bodies as small as 2.5 mm in diameter. Retrograde injection of 10 μM ICG also permitted detection of normal ureter and pinpointed urine leakage caused by injury. ES-TOF mass spectrometry, and absorbance and fluorescence spectral analysis, confirmed that the fluorescent material in urine was chemically identical to CW800-CA.

Conclusions

A convenient IV injection of CW800-CA, or direct injection of ICG, permits high sensitivity visualization of ureters under steady state and abnormal conditions using invisible light.

Keywords: Ureters, Fluorescence, Imaging, Intraoperative Imaging, Indocyanine Green

INTRODUCTION

The intraoperative visualization of ureters embedded in surrounding tissue is a challenge. Ureteral stents, in conjunction with either palpation or an illuminated catheter,1 can be used for surgical guidance in some cases.2 However, stent placement can be difficult and carries with it possible complications,3 and illuminated catheters are expensive. X-ray fluoroscopy can be used in conjunction with either intravenously injected, direct injected,4 or retrograde injected iodine contrast; however, this exposes both patient and caregivers to ionizing radiation. Dyes such as indigo carmine5 and methylene blue6 can be used in either antegrade or retrograde approaches, but contrast is poor, and such dyes are difficult to see if the ureters are embedded in tissue. Thus visible dyes are specific, but not sensitive.7

Ureteral injury is rare, but when it does occur, can be a serious problem.8 The major causes of injury are trauma,7 iatrogenic injury during open surgery,9 and injury during catheter or endoscopic intervention. Ureteral injuries are often insidious, being found only after other, more profound injuries have been addressed; this may lead to a worse outcome.7,9 Thus, early detection and prevention of ureteral injury are vitally important.

Optical imaging using invisible near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent light has the potential to address all of these issues (reviewed in 10). Living tissue has relatively low absorbance and scatter in the NIR wavelength range of 700 nm to 900 nm, permitting photons to penetrate relatively deeply. By adding an exogenous NIR fluorophore to the surgical field, any desired target, such as the ureters, can be illuminated with high sensitivity and specificity. Our laboratory has previously described an easy-to-use intraoperative NIR fluorescence imaging system that permits surgeons to visualize surgical anatomy and the otherwise invisible NIR fluorophore simultaneously, non-invasively, with high spatial resolution, and in real-time.11,12

Indocyanine green (ICG) was first submitted to the FDA in 1958 for use as a green dye in cardiac output and liver function measurements. However, it is also a potent NIR fluorophore, and has a remarkably good safety record.13 Newer NIR fluorophores, with improved quantum yields and improved biodistribution and clearance profiles, have also been described. Using large animal model systems approaching the size of humans, we demonstrate in this study how either a convenient IV injection, or catheter-based retrograde injection, of NIR fluorophore provides highly sensitive and specific intraoperative imaging of the ureters. Ureters can now be visualized even when embedded in surrounding tissue, and injury can be assessed in real-time using invisible light.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of NIR Fluorophores

CW800-CA, the carboxylic acid form of IRDye™ 800CW NIR dye, was from LI-COR (Lincoln, NE). CW800-CA was stored as a 10 mM solution in dimethyl sulfoxide at -80°C in the dark, and was diluted into saline immediately before IV injection.

Intraoperative NIR Fluorescence Imaging System

The intraoperative NIR fluorescence imaging system optimized for animal surgery has been described in detail previously.11 It is composed of two wavelength-isolated excitation sources, one generating 0.5 mW/cm2 400-700 nm “white” light, and the other generating 5 mW/cm2 725-775 nm light over a 15 cm diameter field of view. Photon collection is achieved with custom-designed optics that maintain the separation of the white light and NIR fluorescence emission (i.e., 700-725 nm or > 795 nm) channels. Spatial resolution at a field-of-view of 20 × 15 cm is 625 μm, and at a field-of-view of 4 × 3 cm is 125 μm.

Using custom LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX) software, anatomic (white light) and functional (NIR fluorescence light) images can be displayed separately and merged. To create a single image that displays both anatomy (color video) and function (NIR fluorescence), the NIR fluorescence image was pseudo-colored (e.g., in lime green) and overlaid with 100% transparency on top of the color video image of the same surgical field. All images are refreshed up to 15 times per second. The entire apparatus is suspended on an articulated arm over the surgical field, thus permitting non-intrusive imaging.

Animals

Animals were used in accordance with an approved institutional protocol. Male Sprague-Dawley rats of 350 g from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized with 65 mg/kg intraperitoneal pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal sodium; Abbott Lab, North Chicago, IL). Adult female Yorkshire pigs of 35 kg (E.M. Parsons & Sons, Hadley, MA) were induced with 4.4 mg/kg intramuscular Telazol (Fort Dodge Labs, Fort Dodge, IA), intubated, and maintained with 1.5-2% isoflurane (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, IL).

Ureter Imaging and Signal Quantification

In 12 rats, the ureter was visualized by IV injection of 50 μL of CW800-CA, at a concentration of 10 μM (1.5 μg/kg; N=3), 20 μM (3.0 μg/kg; N=3), 50 μM (7.5 μg/kg; N=3), or 100 μM (15 μg/kg; N=3), to quantify the optimal concentration for ureteral imaging. Fluorescence emission intensities of ureter, kidney, and abdominal wall were measured at 3, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min post-injection. In 6 anesthetized pigs, 5 mL of 50 μM (7.5 μg/kg; N=3) or 100 μM (15 μg/kg; N=3) of CW800-CA was injected intravenously. As indicated, cystostomy (N=2) was used to place 2.5 mm diameter beads into the lumen of the ureter. The NIR fluorescence camera acquisition time ranged from 60 to 100 msec (i.e., 10 to 16 images per second). The signal-to-background ratio (SBR) for the ureter was measured by using as background the signal from an identically sized and shaped region of interest over adjacent abdominal wall or kidney.

Gel-Filtration Chromatography

Urine was flash frozen in LN2 and stored at -80°C until analysis. To remove high molecular weight proteins and other molecules that would interfere with mass spectroscopic analysis, urine was thawed, diluted two-fold in PBS, and separated on a P6 gel-filtration cartridge (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min using PBS as mobile phase. The NIR fluorescent peak from urine was collected using on-line, simultaneous absorbance and fluorescence spectrometry as described previously.14

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

50 μL from the NIR fluorescent P6 column peak was analyzed on a custom Waters (Milford, MA) LCT ES-TOF LC/MS system equipped with dual-absorbance detector, fluorescence detector, Sedex model 75 evaporative light scatter detector (ELSD; Richards Scientific, Novato, CA), and lockspray as described in detail previously.14 The absorbance detector was set at 254 nm and 700 nm (the maximum permitted wavelength). The fluorescence detector was set at 770 nm excitation and 800 nm emission. Leucine enkephalin (1 ng/μL) in water:acetonitrile (1:1) was used as a mass reference for the lockspray. Buffer A was 10 mM TEAA, pH 7.0 (Glen Research, Sterling, VA), and Buffer B was methanol (Aaper Alcohol and Chemical, Shelbyville, KY). Using a gradient of 5% to 70% Buffer B over 25 min, hold for 5 min, and re-equilibrate at 5% Buffer B over 5 min, the urine sample was resolved on a 4.6 × 150 mm Symmetry C18 column (Waters) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Eluate was split to the ELSD and MS, with the latter set to negative (ES-) mode, 30 V cone voltage, and 3000 V capillary voltage. Desolvation and source temperature were set to 350°C and 140°C, respectively. Data were analyzed with MassLynx (Waters) software.

RESULTS

Ureteral Imaging in Rats

The ureter and urine had virtually no NIR autofluorescence prior to contrast agent injection (data not shown). After IV injection of CW800-CA into rat, the ureter was visualized after 3-5 min with a maximum SBR obtained at 10 min post-injection (Figure 1A). Of particular utility is the merged image (i.e., pseudo-colored NIR fluorescence image overlaid onto the color video image), which provides anatomical orientation to the surgeon. Indeed, peristaltic flow of the ureter can be visualized in real-time in both the NIR fluorescence and merged images. After peaking, SBR of the ureter decreases linearly over time, with the rate relatively independent of dose between 1.5 μg/kg and 15 μg/kg of CW800-CA. In the rat, a dose of 7.5 μg/kg of CW800-CA showed the highest SBR, ≥ 4.0, at 10 min post-injection (Figure 2).

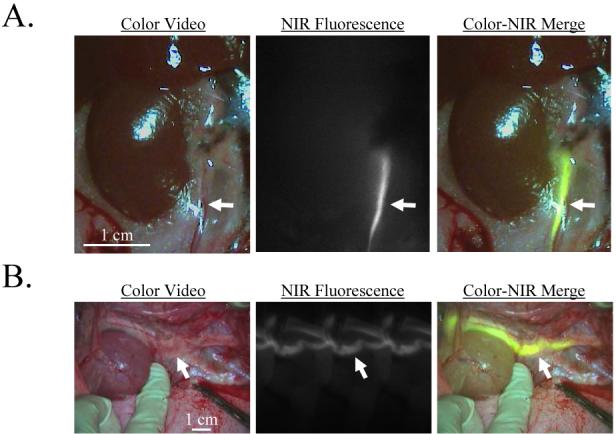

Figure 1. Real-time visualization of the ureters using invisible light.

Minutes after IV injection of A) 7.5 μg/kg CW800-CA into rat and B) 7.5 μg/kg into pig, the ureters become highly NIR fluorescent (arrows). Shown are the color video (left), NIR fluorescence (middle), and merged images of the two (right). NIR fluorescence images have identical exposure times (100 msec) and normalizations. Data are representative of N = 4 independent experiments in rat and N = 6 independent experiments in pig.

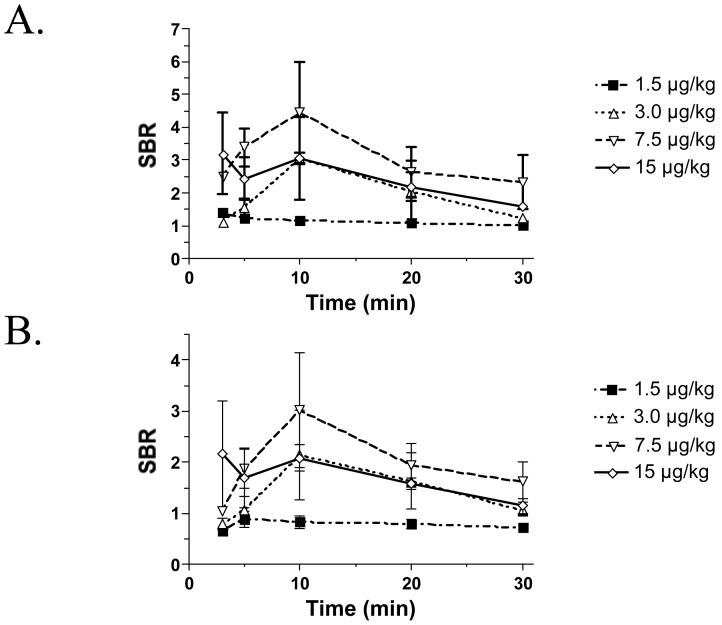

Figure 2. Quantification of SBR kinetics for ureteral NIR fluorescence emission.

The SBR (mean ± SEM) of the ureter relative to A) abdominal wall and B) kidney was quantified over time after IV injection of 1.5 μg/kg, 3.0 μg/kg, 7.5 μg/kg, and 15 μg/kg CW800-CA in N = 3 rats each.

Ureteral Imaging in Pigs

These results were confirmed in a pig model approaching the size of humans. Again, IV injection of 7.5 μg/kg CW800-CA into 35 kg adult female Yorkshire pigs resulted in the highest SBR, with visualization of the ureter starting at 10 min post-injection. An ureteral SBR ≥ 2.0 was sustained for at least 30 min in the pig. Importantly, small (2.5 mm diameter) foreign bodies could be detected easily with our imaging system (Figure 3A).

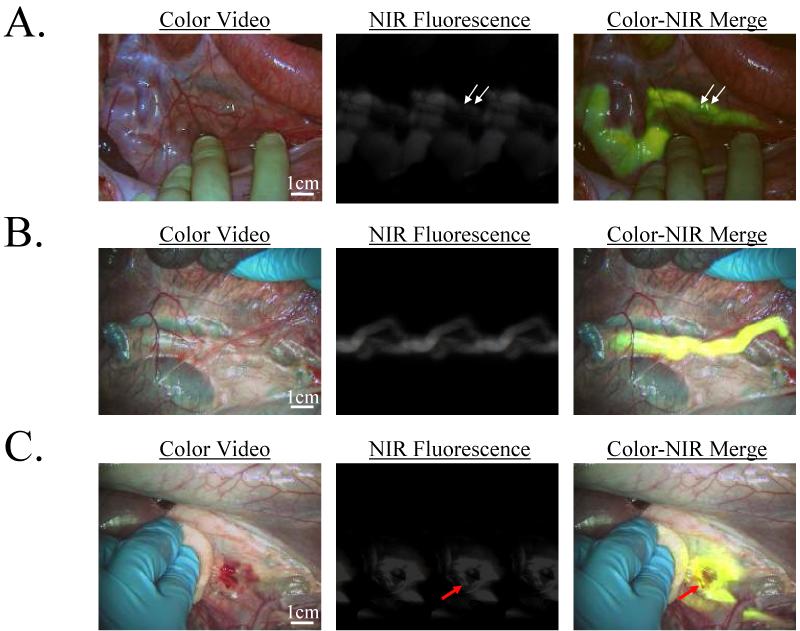

Figure 3. Assessment of ureteral patency and injury in large animals approaching the size of humans.

- After IV injection of 7.5 μg/kg CW800-CA in the pig, the ureters could be visualized for the next 60 min. Shown is the identification of two foreign bodies (2.5 mm diameter beads; arrows) within the lumen of the ureter. NIR fluorescence exposure times were 100 msec. Data are representative of results from N = 4 independent experiments.

- Retrograde injection of 10 ml of 10 μM ICG in saline provided immediate visualization of the ureters. NIR fluorescence exposure times were 60 msec. Data are representative of N = 2 independent experiments.

- A site of injury to the ureter made during tissue dissection, in this case from a scalpel, can be pinpointed immediately (red arrow) and repaired. NIR fluorescence exposure times were 60 msec. Data are representative of N = 2 independent experiments.

Chemical Form of the NIR Fluorophore in the Urine

Although the chemical substance in the urine was NIR fluorescent, we asked whether the substance that provided such high ureteral contrast was intact CW800-CA or a metabolite. After pre-separation of the NIR fluorescent peak from urine using gel-filtration chromatography (see Materials and Methods), HPLC-MS analysis showed a single non-void volume NIR fluorescent peak at 22 min (Figure 4A). The chemical formula of CW800-CA and its exact mass are C46H51N2O15 S43- and 999.22, respectively. Mass spectroscopic analysis of the NIR fluorescent peak from urine showed a fragmentation pattern ([M+H]-2/2 and [M+Na]-2/2) consistent with intact CW800-CA (Figure 4B). Of note, the HPLC (Figure 4A) and mass spectroscopic pattern (Figure 4B) of reference CW800-CA was identical, suggesting that CW800-CA was excreted into urine intact, and was the source of the ureteral contrast.

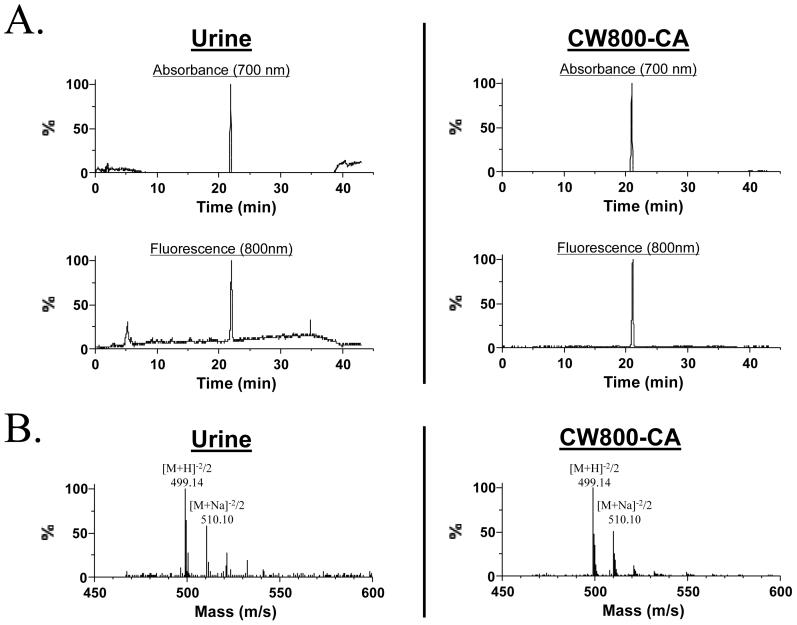

Figure 4. Mass spectroscopic analysis of urine after IV injection of CW800-CA.

A) 700 nm absorbance (top) and 800 nm fluorescence (bottom) of urine (left) and pure CW800-CA (right) after separation on a C18 column. B) The single non-void volume, NIR fluorescent peak from each chromatography column was subjected to mass spectroscopic analysis, with the obtained fragmentation pattern shown. Data are representative of N = 4 independent experiments.

Ureteral Visualization in Pig using ICG

Since CW800-CA is not presently available for human use, we repeated the pig experiments using administration of ICG, a potent NIR fluorophore already FDA-approved for other indications. As shown in Figure 3B, retrograde injection of 10 μM ICG into the ureters resulted in immediate visualization of the ureters, even when embedded in surrounding tissue. In the case of ureteral injury, ICG leakage can be visualized directly, in real-time, permitting immediate localization of the injury site (Figure 3C).

DISCUSSION

Optical imaging using invisible NIR fluorescent light has several advantages over currently available intraoperative techniques. First, visualization of the ureters does not require ionizing radiation, and uses only safe levels of excitation light. Second, because fluorescence emission is invisible to the human eye, the surgical field is not stained or changed in any way. The blue dyes that are currently used stain the surgical field and have relatively poor contrast. Third, imaging can be performed in real-time (up to 15 frames per second) with the merged image from the color video and NIR fluorescent cameras providing anatomical landmarks. Finally, the imaging system itself has no moving parts and makes no contact with the patient (i.e., it is positioned 18″ above the surgical field). The major disadvantage is that the ureter must be at least partially exposed to perform the imaging, making the technique unlikely to replace nuclear renal imaging or other pre-surgical tests.

For urology applications, the technology we describe will permit definitive localization of the ureters embedded within surrounding tissue, but will also permit non-invasive assessment of lumenal obstruction. As demonstrated using 2.5 mm diameter beads, voids in the ureter lumen are visualized using NIR fluorescence in a similar manner to x-ray fluorescence. More important, we demonstrate that sites of ureteral injury and urine leakage can be pinpointed with high precision and in real-time, thus minimizing the likelihood of occult injury.

For non-urology applications, NIR fluorescence imaging permits visualization, and thus avoidance, of the ureters during general surgical procedures such as colon cancer resection, and obstetrics procedures such as Cesarean section. Both of these surgeries carry a small but finite risk of ureteral injury, which might be expected to improve when real-time intraoperative visualization of the ureters becomes available.

The ideal NIR fluorescent contrast agent for ureteral imaging would be intravenously injected at a low dose, yet provide sensitive ureteral imaging over an extended period of time. Based on our data, molecules such as CW800-CA appear to perform as desired, and indeed, are excreted into urine without chemical modification. Inert bulking groups can be chemically conjugated to NIR fluorophores to extend blood half-life and increase the window available for ureteral imaging. However, for a fixed injected dose, there is an inherent tradeoff between fluorophore concentration in the blood and fluorophore concentration in the ureters, which needs to be considered. It is also important to titrate the dose of NIR fluorescent contrast agent such that SBR is optimal, and the window for visualization is adequate, for the particular surgical procedure being employed. NIR fluorescence emission is known to quench at fluorophore concentrations above approximately 10 μM,15 so increasing urine concentration past this level results in higher tissue background and a lower SBR.

Although the preferred, and most convenient, administration of a ureteral contrast agent is via IV injection, the only FDA-approved NIR fluorophore currently available (for other indications) is ICG, which is rapidly cleared by the liver and has no detectable urinary excretion. Nevertheless, we demonstrate in this study that retrograde injection, and presumptively antegrade injection, of ICG provides excellent visualization of the ureters with a performance similar to CW800-CA. Hence, ICG could be considered as a temporary alternative to CW800-CA and other optimal agents until such agents are available clinically.

The simple reflectance type imaging system described in this study has one critical limitation that must be appreciated by the surgeon. Due to the combined effects of absorption and scatter, NIR fluorescent light can only penetrate a few mm in solid tissue, up to 1 cm in fat,16 and up to 5 cm in lung.17 Therefore, visualization of the ureters is limited by the thickness and type of tissue surrounding them, with NIR fluorescence emission falling off exponentially with tissue depth. Fortunately, though, the converse is also true. As one surgically approaches the ureter through overlying tissue, its NIR fluorescent signal will increase exponentially. Newer techniques for NIR fluorescence imaging promise 2 to 4 cm of depth penetration prior to tissue dissection,18,19 and we and others are developing miniaturized versions of the present imaging system for laparoscopy.

CONCLUSION

We demonstrate high sensitivity, real-time visualization of the ureters using the combination of an intraoperative NIR fluorescence imaging system and NIR fluorescent contrast agents. Using invisible NIR light, the ureters can be found, avoided, and/or functionally assessed in the operating setting, without the use of ionizing radiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alec M. De Grand for assistance with imaging system software, Barbara L. Clough for editing, and Grisel Vazquez for administrative assistance. This work was funded by NIH grants R01-CA-115296, R01-EB-005805, and R21-CA-110185 to JVF.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ES-TOF

electrospray time-of-flight

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- ICG

indocyanine green

- IV

intravenous

- MS

mass spectrometry

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4

- SBR

signal-to-background ratio

REFERENCES

- 1.Chahin F, Dwivedi AJ, Paramesh A, Chau W, Agrawal S, Chahin C, et al. The implications of lighted ureteral stenting in laparoscopic colectomy. Jsls. 2002;6:49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bothwell WN, Bleicher RJ, Dent TL. Prophylactic ureteral catheterization in colon surgery. A five-year review. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:330. doi: 10.1007/BF02053592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood EC, Maher P, Pelosi MA. Routine use of ureteric catheters at laparoscopic hysterectomy may cause unnecessary complications. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;3:393. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(96)80070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S, Pearle MS. Imaging for percutaneous renal access and management of renal calculi. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:353. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jabs CF, Drutz HP. The role of intraoperative cystoscopy in prolapse and incontinence surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1368. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.119072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang AC. The techniques of trocar insertion and intraoperative urethrocystoscopy in tension-free vaginal taping: an experience of 600 cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:293. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.0364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandes S, Coburn M, Armenakas N, McAninch J. Diagnosis and management of ureteric injury: an evidence-based analysis. BJU Int. 2004;94:277. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliott SP, McAninch JW. Ureteral injuries: external and iatrogenic. Urol Clin North Am. 2006;33:55. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Awadi K, Kehinde EO, Al-Hunayan A, Al-Khayat A. Iatrogenic ureteric injuries: incidence, aetiological factors and the effect of early management on subsequent outcome. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:235. doi: 10.1007/s11255-004-7970-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Grand AM, Frangioni JV. An operational near-infrared fluorescence imaging system prototype for large animal surgery. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2003;2:553. doi: 10.1177/153303460300200607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakayama A, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ, Frangioni JV. Functional near-infrared fluorescence imaging for cardiac surgery and targeted gene therapy. Mol Imaging. 2002;1:365. doi: 10.1162/15353500200221333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benya R, Quintana J, Brundage B. Adverse reactions to indocyanine green: a case report and a review of the literature. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1989;17:231. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810170410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humblet V, Misra P, Frangioni JV. An HPLC/mass spectrometry platform for the development of multimodality contrast agents and targeted therapeutics: prostate-specific membrane antigen small molecule derivatives. Contrast Media Mol Imag. 2006;1:196. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohnishi S, Lomnes SJ, Laurence RG, Gogbashian A, Mariani G, Frangioni JV. Organic alternatives to quantum dots for intraoperative near-infrared fluorescent sentinel lymph node mapping. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:172. doi: 10.1162/15353500200505127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Lim YT, Soltesz EG, De Grand AM, Lee J, Nakayama A, et al. Near-infrared fluorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel lymph node mapping. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:93. doi: 10.1038/nbt920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soltesz EG, Kim S, Laurence RG, DeGrand AM, Parungo CP, Dor DM, et al. Intraoperative sentinel lymph node mapping of the lung using near-infrared fluorescent quantum dots. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:269. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ntziachristos V, Bremer C, Weissleder R. Fluorescence imaging with near-infrared light: new technological advances that enable in vivo molecular imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:195. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1524-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sevick-Muraca EM, Houston JP, Gurfinkel M. Fluorescence-enhanced, near infrared diagnostic imaging with contrast agents. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2002;6:642. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]