History and Physical Examination

A 73-year-old man was referred with a chief complaint of a left posterior thigh mass. The mass had been present for 2 months. The patient reported mild pain that was intermittent, aching, and sharp and occurred only after prolonged sitting. He had no history of trauma, fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, or night pain. His medical history included renal cell carcinoma treated with a right nephrectomy 21 years earlier, Type II diabetes of 15 years’ duration, and a benign pancreatic mass. An MRI of the mass had recently been performed. The rest of the patient’s history was unremarkable.

On physical examination of the left posterior thigh, a nontender soft tissue mass was palpated that was also firm, deep, and fixed with contraction of the hamstring muscles. There were no skin changes, erythema, or overlying warmth. Active and passive range of motion of the hip and knee were full and painless. The neurologic examination of the left lower extremity was normal. Gait was normal. The remainder of the musculoskeletal examination was normal.

MRI scan (Fig. 1) of the lesion was performed without initial radiographs.

Fig. 1A–D.

(A) A T1-weighted axial MR image with fat saturation shows the intramuscular location of the lesion. (B) A T2-weighted axial MR image with fat saturation shows the high water content of the lesion. (C) A sagittal STIR MR image illustrates the large craniocaudal size of the lesion. (D) A T1-weighted sagittal MR image illustrates the blood vessels supplying the lesion.

Based on the history, physical examination, and the imaging studies, what is the differential diagnosis?

Imaging Interpretation

MRI without contrast of the left thigh showed a well-circumscribed mass 16 cm × 7.5 cm in its greatest diameter (Fig. 1A–C). The lesion was located in the biceps femoris muscle in the posterior aspect of the midthigh. The mass abutted the fascia of adjacent muscles on either side and the subcutaneous fat posteriorly. It was heterogeneous and had many large vessels, particularly on its surface (Fig. 1D). The lesion had a hypointense to isointense signal to muscle on T1-weighted images and a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images.

Differential Diagnosis

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Liposarcoma

Leiomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Hemangioma

Metastasis

A needle biopsy was performed in the operating room with a dozen core samples taken (Fig. 2).

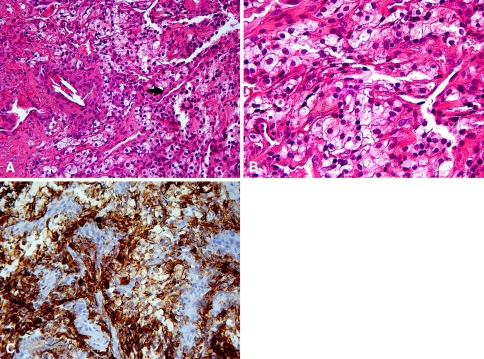

Fig. 2A–C.

(A) A low-power histology image shows the sheets of cells with eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm punctuated by a fine vascular network (arrow) (stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×20). (B) A higher-power view demonstrates the cells with prominent cytoplasmic clearing known as clear cells (stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×40). (C) Immunohistochemistry staining illustrates the strong and diffuse cytoplasmic staining for CAM 5.2 (original magnification, ×20).

Based on the history, physical findings, imaging studies, and histologic picture, what is the diagnosis and how should this lesion be treated?

Histology Interpretation

On gross examination, the specimen consisted of multiple cores of yellow-tan tissue measuring from 0.5 to 1.5 cm.

Histologic sections showed a malignant epithelial neoplasm consisting of fine papillae with chicken wire vascular channels comprising cells with prominent clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2A–B). There was mild nuclear pleomorphism with occasional nucleoli.

Immunohistochemistry staining showed the cells strongly and diffusely positive for low-molecular-weight keratins, CAM 5.2 (Fig. 2C) and AE1/AE3; focally positive for CD10 and renal cell carcinoma antigen; and negative for S-100 (expressed in a variety of tumors), cytokeratin-7 (CK-7, epithelial-like sarcoma marker), cytokeratin-20 (CK-20, epithelial-like sarcoma marker), HMB-45 (melanocytic marker also present in some benign lesions), Melan-A (adrenocortical neoplasm marker), thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), tyrosinase, smooth muscle actin, thyroglobulin, leukocyte common antigen, desmin, and hepatocyte-specific antigen.

Diagnosis

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Discussion and Treatment

Less than 1% of all metastases from carcinomas are found in skeletal muscle [23]. Two musculoskeletal oncology centers identified 20 cases of skeletal muscle metastases from carcinoma over an 11-year period [39]. Another study found 12 cases from three oncology centers over a 10-year period [7]. The most common skeletal muscle carcinoma metastases are from the lung and gastrointestinal tract [7, 11]. Other primary tumors that rarely metastasize to skeletal muscle include soft tissue sarcoma, renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and head and neck cancers [7, 11].

Age, location, and lack of pain in this patient were suspicious for soft tissue sarcoma. Location within skeletal muscle is consistent with rhabdomyosarcoma; however, the older age of the patient made this less likely. Soft tissue hemangiomas are more common, but this was less likely because they often cause pain. Skeletal muscle metastases commonly present with pain [7, 11]. Histology is necessary to differentiate between these rare lesions and an unusual presentation of metastasis. Identifying a primary tumor versus a metastasis is critical because of the great differences in their treatment and prognosis [11].

Renal cell carcinoma most commonly metastasizes to the lungs, lymph nodes, bone, and liver [12, 31]. Skeletal muscle metastasis rates of 0.6% and 1.1% were found in two large studies of renal cell carcinoma patients [4, 30]. Two other large studies of 1451 and 586 patients had no skeletal muscle metastases [31, 37].

Reviewing the literature, we found 27 cases of renal cell carcinoma skeletal muscle involvement. The most common sites were the thigh (30%), upper arm (18%), and shoulder (15%) (Fig. 3) [1, 2, 5, 6, 8–11, 13–19, 21, 25, 27, 28, 32, 34–36, 41–43]. Five cases had multiple skeletal muscle metastases (19%) [8, 13, 21, 27, 28]. Slight to mild pain was reported in eight cases (24%) [2, 5, 11, 16, 17, 19, 25, 42].

Fig. 3.

A diagram illustrates the distribution of skeletal muscle metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (percentage, with the number of cases in parentheses) found in the literature [1, 2, 5, 6, 8–11, 13–19, 21, 25, 27, 28, 32, 34–36, 41–43]. Modified and reprinted with permission from Patrick Hermans. © Patrick Hermans.

Several theories have attempted to explain why metastases are rare in skeletal muscle in spite of its rich blood supply and large percentage of body mass. Production of lactic acid by skeletal muscle may result in resistance to angiogenesis thereby impeding tumor establishment [15, 33]. Frequent contractions of the muscle may prevent cancer seeding and metastatic growth through wide variation in blood flow [26]. High concentrations of free radicals and local temperature fluctuations may also hinder development of metastases in skeletal muscle [16]. Additionally, specific receptors influence metastatic potential in renal cell carcinoma [24, 40] and these receptors may be absent or scarce in muscle. One study [20] suggests skeletal muscle trauma during active disease may increase the risk of metastasis at that site.

The mass in this case is larger and presented later than previously described renal cell carcinoma muscle metastases. Reported sizes range from 1.5 to 10 cm (average, 5.4 cm) in largest diameter [1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13, 16, 18, 21, 25, 27, 32, 36, 41]. While 11% of renal cell carcinoma metastases occur more than 10 years after nephrectomy [22], skeletal muscle metastasis after long-term survival remains uncommon. The average time to muscle metastases after nephrectomy found in the literature was 9.1 years (range, 6 months to 19 years) [2, 6, 9, 10, 13–17, 19, 21, 25, 27, 32, 34–36, 41, 43]. It is important for orthopaedic surgeons to recognize that delayed skeletal muscle metastasis does occur so that early diagnosis and intervention is possible.

Muscle metastases from carcinoma are typically hypointense to slightly hyperintense relative to skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images and isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted images [6, 8, 16, 21, 25, 27]. MRI with gadolinium enhancement is useful in evaluating the vascularity of the tumor, differentiating areas of necrosis [16, 39], and planning operative treatment [21]. MRI findings alone are insufficient to differentiate metastatic lesions from soft tissue sarcomas [7, 11]. Biopsy is needed to make a definitive diagnosis. Plain radiography has little use in differentiating metastases from soft tissue sarcoma [11].

Grossly, renal cell carcinoma metastases can have a grey-white, multinodular appearance. Focal necrosis and hemorrhage may be seen. The tumor may have a fibrous capsule [1, 8, 25]. Histologic sections demonstrate large cells that can be either columnar or cuboidal. The histologic pattern varies from papillary to glandular to undifferentiated, and the cells appear clear, with central hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli [1, 11, 18, 27]. Spindlelike cells may be present and may be mistaken for sarcoma cells [1, 17].

Periodic acid-Schiff stain shows the high cytoplasmic glycogen content of renal cell carcinoma epithelial cells, and silver stain identifies their glandular nests. Immunohistochemical markers, such as low-molecular-weight cytokeratin (CAM 5.2), epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and renal cell carcinoma marker, should be positive, greatly aiding in diagnosis [29, 38].

Treatment of renal cell carcinoma metastases to skeletal muscle depends on the overall clinical picture of the patient. Surgical excision may be attempted in the absence of widespread disease [1, 2, 6, 9, 15, 19, 25, 27, 35], although recurrence has been reported [15]. Disseminated disease to the lung, bone, and liver requires treatment with chemotherapy and/or radiation [5, 16, 17]. Renal cell carcinoma can spontaneously regress, suggesting a response from the immune system [3, 12]. Consequently, therapies were developed using immunoreactive cytokines including IL-2 and interferon-α, though results have been variable [8, 15, 21, 32, 34, 43].

We present a 73-year-old man with a left thigh mass and minimal symptoms 21 years after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. A diagnosis of soft tissue sarcoma was suspected due to the large size and appearance of the lesion, but the final diagnosis was metastatic renal cell carcinoma. This case highlights the fact that a metastasis should be considered for a skeletal muscle mass in patients with a history of renal cell carcinoma even though they received adequate treatment and had a long disease-free interval.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eileen A. Crawford, MD, Pennsylvania Hospital at the University of Pennsylvania, for her assistance with this case.

Footnotes

One or more authors (JJK) have received funding (research fellowship) from Stryker-Howmedica-Osteonics, Mahwah, NJ.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved or waived approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Alexiou C, Kau RJ, Dietzfelbinger H, Kremer M, Spiess JC, Schratzenstaller B, Arnold W. Extramedullary plasmacytoma: tumor occurrence and therapeutic concepts. Cancer. 1999;85:2305–2314. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Alimonti A, Di Cosimo S, Maccallini V, Ferretti G, Pavese I, Satta F, Di Palma M, Vecchione A. A man with a deltoid swelling and paraneoplastic erythrocytosis: case report. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:5181–5184. [PubMed]

- 3.Atkins MB, Regan M, McDermott D. Update on the role of interleukin 2 and other cytokines in the treatment of patients with stage IV renal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(18 Pt 2):6342S–6346S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bennington J, Kradjian R. Site of metastases at autopsy in 523 cases of renal carcinoma. In: Bennington J, Kradjian R, eds. Renal Carcinoma. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1967:156–169.

- 5.Bong MR, Capla EL, Egol KA, Sorkin AT, Distefano M, Buckle R, Chandler RW, Koval KJ. Osteogenic protein–1 (bone morphogenic protein-7) combined with various adjuncts in the treatment of humeral diaphyseal nonunions. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2005;63:20–23. [PubMed]

- 6.Chen CK, Chiou HJ, Chou YH, Tiu CM, Wu HT, Ma S, Chen W, Chang CY. Sonographic findings in skeletal muscle metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:1419–1423; quiz 1424–1415. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Damron TA, Heiner J. Distant soft tissue metastases: a series of 30 new patients and 91 cases from the literature. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:526–534. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.de Portugal Fernandez del Rivero T, Alvarez Gallego JV, Sastre Valera J, Alonso Romero JL, Gonzalez Larriba JL. [A metastatic muscle mass as the first manifestation of renal-cell cancer: a case report and review of the literature] [in Spanish]. An Med Interna. 1997;14:184–186. [PubMed]

- 9.Di Tonno F, Rigon R, Capizzi G, Bucca D, Di Pietro R, Zennari R. Solitary metastasis in the gluteus maximus from renal cell carcinoma 12 years after nephrectomy: case report. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1993;27:143–144. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Galera-Ruiz H, Martin-Gomez R, Esteban-Ortega F, Congregado-Loscertales M, Garcia Escudero A. Extramuscular soft tissue myxoma of the lateral neck. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 2001;122:259–261. [PubMed]

- 11.Herring CL Jr, Harrelson JM, Scully SP. Metastatic carcinoma to skeletal muscle: a report of 15 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355:272–281. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Holland JM. Proceedings: Cancer of the kidney: natural history and staging. Cancer. 1973;32:1030–1042. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hur J, Yoon CS, Jung WH. Multiple skeletal muscle metastases from renal cell carcinoma 19 years after radical nephrectomy. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:238–241. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Imaizumi T, Sohma T, Hotta H, Teto I, Imaizumi H, Kaneko M. Associated injuries and mechanism of atlanto-occipital dislocation caused by trauma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1995;35:385–391. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Issakov J, Flusser G, Kollender Y, Merimsky O, Lifschitz-Mercer B, Meller I. Computed tomography-guided core needle biopsy for bone and soft tissue tumors. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:28–30. [PubMed]

- 16.Judd CD, Sundaram M. Radiologic case study: metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Orthopedics. 2000;23:1026, 1123–1124. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Karakousis CP, Rao U, Jennings E. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to skeletal muscle mass: a case report. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:287–293. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kishore B, Khare P, Jain R, Bisht S, Paik S. Unsuspected metastatic renal cell carcinoma with initial presentation as solitary soft tissue lesion: a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49:424–425. [PubMed]

- 19.Linn JF, Fichtner J, Voges G, Schweden F, Storkel S, Hohenfellner R. Solitary contralateral psoas metastasis 14 years after radical nephrectomy for organ confined renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1996;156:173. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Magee T, Rosenthal H. Skeletal muscle metastases at sites of documented trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:985–988. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Manzelli A, Rossi P, De Majo A, Coscarella G, Gacek I, Gaspari AL. Skeletal muscle metastases from renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Tumori. 2006;92:549–551. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.McNichols DW, Segura JW, DeWeerd JH. Renal cell carcinoma: long-term survival and late recurrence. J Urol. 1981;126:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Menard O, Parache R. [Muscle metastasis of cancers] [in French]. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1991;142:423–428. [PubMed]

- 24.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, Hudes GR, Wilding G, Figlin RA, Ginsberg MS, Kim ST, Baum CM, DePrimo SE, Li JZ, Bello CL, Theuer CP, George DJ, Rini BI. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Munk PL, Gock S, Gee R, Connell DG, Quenville NF. Case report 708: metastasis of renal cell carcinoma to skeletal muscle (right trapezius). Skeletal Radiol. 1992;21:56–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Muslow F. Metastatic carcinoma of skeletal muscles. Arch Pathol. 1943;35:112–114.

- 27.Nabeyama R, Tanaka K, Matsuda S, Iwamoto Y. Multiple intramuscular metastases 15 years after radical nephrectomy in a patient with stage IV renal cell carcinoma. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6:189–192. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Nakada J, Onodera S, Shirai T, Igarashi H, Nishida A, Iwasaki M, Takeishi M. [A case of muscle metastasis of renal cell carcinoma treated by local resection and tensor fascia lata myocutaneous flaps] (in Japanese). Hinyokika Kiyo. 1994;40:1013–1016. [PubMed]

- 29.Polydorides AD, Rosenblum MK, Edgar MA. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:641–645. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Riches EW, Griffiths IH, Thackray AC. New growths of the kidney and ureter. Br J Urol. 1951;23:297–356. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Saitoh H. Distant metastasis of renal adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:1487–1491. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Schatteman P, Willemsen P, Vanderveken M, Lockefeer F, Vandebroek A. Skeletal muscle metastasis from a conventional renal cell carcinoma, two years after nephrectomy: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2002;102:351–352. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Seely S. Possible reasons for the high resistance of muscle to cancer. Med Hypotheses. 1980;6:133–137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Shibayama T, Hasegawa S, Nakamura S, Tachibana M, Jitsukawa S, Shiotani A, Morinaga S. Disappearance of metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the base of the tongue after systemic administration of interferon-alpha. Eur Urol. 1993;24:297–299. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Stener B, Henriksson C, Johansson S, Gunterberg B, Pettersson S. Surgical removal of bone and muscle metastases of renal cancer. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55:491–500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Taira H, Ishii T, Inoue Y, Hiratsuka Y. Solitary psoas muscle metastasis after radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol. 2005;12:96–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Tolia T, Whitmore W. Solitary metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1975;114:836. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Tsukada K, Church JM, Jagelman DG, Fazio VW, McGannon E, George CR, Schroeder T, Lavery I, Oakley J. Noncytotoxic drug therapy for intra-abdominal desmoid tumor in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:29–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Tuoheti Y, Okada K, Osanai T, Nishida J, Ehara S, Hashimoto M, Itoi E. Skeletal muscle metastases of carcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:210–214. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Weber KL, Doucet M, Price JE. Renal cell carcinoma bone metastasis: epidermal growth factor receptor targeting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;415(suppl):S86–S94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Witthaut J, Steffens K, Koob E. [An unusual case of metastasis to the soft tissues of the palm of the hand with compression of the median and ulnar nerve by kidney cancer: case report] [in German]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 1994;26:137–140. [PubMed]

- 42.Yadav R, Ansari MS, Dogra PN. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as solitary foot metastasis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2004;36:329–330. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Yanagie H, Miyamoto H, Yoshizaki I, Takahashi T, Sekiguchi M, Fujii G. [A case of metastasis of renal cell carcinoma to the abdominal wall 13 years after nephrectomy] [in Japanese]. Gan No Rinsho. 1987;33:1950–1953. [PubMed]