Abstract

Given the fact that infectious agents contribute to around 18% of human cancers worldwide, it would seem prudent to explore their role in neoplasms of the ocular adnexa: primary malignancies of the conjunctiva, lacrimal glands, eyelids, and orbit. By elucidating the mechanisms by which infectious agents contribute to oncogenesis, the management, treatment, and prevention of these neoplasms may one day parallel what is already in place for cancers such as cervical cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma. Antibiotic treatment and vaccines against infectious agents may herald a future with a curtailed role for traditional therapies of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Unlike other malignancies for which large epidemiological studies are available, analyzing ocular adnexal neoplasms is challenging as they are relatively rare. Additionally, putative infectious agents seemingly display an immense geographic variation that has led to much debate regarding the relative importance of one organism versus another. This review discusses the pathogenetic role of several microorganisms in different ocular adnexal malignancies, including human papilloma virus in conjunctival papilloma and squamous cell carcinoma, human immunodeficiency virus in conjunctival squamous carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus or human herpes simplex virus-8 (KSHV/HHV-8) in conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori,), Chlamydia, and hepatitis C virus in ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. Unlike cervical cancer where a single infectious agent, human papilloma virus, is found in greater than 99% of lesions, multiple organisms may play a role in the etiology of certain ocular adnexal neoplasms by acting through similar mechanisms of oncogenesis, including chronic antigenic stimulation and the action of infectious oncogenes. However, similar to other human malignancies, ultimately the role of infectious agents in ocular adnexal neoplasms is most likely as a cofactor to genetic and environmental risk factors.

Keywords: Chlamydia psittaci (C. psittaci), Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), human herpes simplex virus-8 (HHV-8), human papilloma virus (HPV), Kaposi sarcoma, MALT lymphoma, ocular adnexa, papilloma, squamous cell carcinoma

I. Introduction

It has been established that infectious agents play an important role in the etiology of certain human malignancies, and are thought to be responsible for around 18% of the worldwide cancer burden (less than 10% in developed nations and up to 27% in developing nations).110,177,183 Much of the burden of cancer incidence, morbidity, and mortality occurs in the developing world, with infectious agents attributing most to malignancies of the cervix (human papilloma virus [HPV]), stomach (Helicobacter pylori [H. pylori]), and liver (hepatitis B virus).115

The eye and ocular adnexal region, affected by hundreds of histologically different types of neoplasms,31 has the greatest variety of malignancies in the human body. Using data from the National Cancer Institute over the period 1996-2006, one can calculate that neoplasms (carcinomas and lymphomas) of the eye and ocular adnexal region constitute less than 0.2% of new cancer cases every year in the United States, and account for an even lower number (<0.05%) of annual deaths due to cancer.83,84,108,109,175,176 Nonetheless, they remain lesions encountered in ophthalmology practice, and in light of the implications for therapy and outcomes, this review aims to analyze the role that infectious agents play in the etiology of certain ocular adnexal neoplasms, lesions affecting the conjunctiva, orbit, lacrimal glands, and eyelids.

A. THE ROLE OF INFECTIOUS AGENTS IN MALIGNANCY

With greater than 99% of invasive cervical cancers containing HPV, certain strains of the organism have been identified as the major cause of disease worldwide.23,24,233 The often subjective screening Pap smear is giving way to polymerase chain reaction amplification (PCR)-based HPV DNA testing that has allowed subclinical disease diagnosis and high risk variants to be identified.238 In 2006, a preventive recombinant vaccine against HPV was approved for use in females prior to first sexual exposure to HPV.199 Also under development are therapeutic vaccines that focus on the main HPV oncogenes, E6 and E7, required for promoting the growth of cancer cells.26,74,131 An analogous impact on cancer management and outcomes can be seen in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma,237 where treatment of low-grade lesions with antibiotics clears not only the infectious organism H. pylori but leads to regression of the tumor14 and a favorable long term prognosis.68

In contrast, such exploration and understanding of the role infectious agents play in the etiology of ocular adnexal neoplasms is a relatively new undertaking. In the 1980s, when human papilloma viruses first received attention for their role in the pathogenesis of anogenital cancers, the literature documented detection of HPV DNA in conjunctival papilloma.125,145,181 Subsequently, various strains of HPV have been identified in conjunctival papilloma9,41,42,62,63 and conjunctival carcinoma,28,150,153,164,196,207,209,217and also in select reports of primary tumors of the lacrimal sac.136,163

As the role of infectious agents in the pathogenesis of ocular adnexal neoplasms is further elucidated by research, a clinical approach similar to that already employed in cervical cancer or gastric MALT lymphoma will be undertaken. Dependent on chronic infection by HPV and H. pylori, respectively, both neoplasms have an anti-infectious approach at the basis of prevention, management, and treatment. In both cases, researching the role of infectious agents in the etiology of the cancer has ultimately affected both prognosis and outcomes.

Much debate in the literature has surrounded the relative importance of different putative infectious agents in certain ocular adnexal neoplasms, with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma being the most widely analyzed malignancy. It seems entirely plausible that different infectious agents in different geographical locations may contribute to pathogenesis, as they may act via similar mechanisms to bring about oncogenesis. With this in mind, this review will examine the literature on the etiological role of infectious agents in the framework of two mechanisms—oncogenes carried by infectious agents and chronic antigenic stimulation.

B. PATHOGENETIC MECHANISMS

1. Oncogenes from Infectious Organisms

Oncogenes in humans are defective proto-oncogenes that cause alterations of the cell cycle mechanisms, thus allowing uncontrolled cell proliferation.22,212 Oncogenes may also be found in infectious agents. It has been shown in cervical cancer that the high risk variants HPV 16 and HPV 18 drive carcinogenesis by inactivating tumor suppressor gene products p53 and Rb in the host with the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7, respectively.97,210 Furthermore, integration of viral sequences into the host genome leads to the constitutive expression of E6/E7 in transformed cervical cells.98,104,162 Studies on conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasms positive for HPV 16 or HPV 18 have also documented E6 mRNA in these lesions.196

2. Chronic Antigenic Stimulation

An additional mechanism whereby infectious agents are involved in the etiology of ocular adnexal or other systemic neoplasms is by inducing a state of chronic antigenic stimulation. For example, in certain cases of non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma it has been shown that the infectious agent does not directly infect and transform lymphoid cells; rather, an the interaction of bacterial or viral antigens with host T-cells and antigen-presenting cells leads to a complex cascade resulting in clonal B-cell or plasma cell expansion.214 Another systemic example is illustrated by the linkage between infection with H. pylori and chronic atrophic gastritis, an inflammatory precursor of gastric adenocarcinoma.178 Additionally, regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after eradication of H. pylori infection with antibiotics is also consistent with this postulate.57,179,247 Recently, similar regression of disease has been reported in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma after treatment with antibiotics against C. psittaci.61

II. Oncogenes, Infectious Agents, and Ocular Adnexal Neoplasia

A. CONJUNCTIVAL PAPILLOMAS

1. Background

The conjunctiva is a mucous membrane with a surface composed of non-keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium intermixed with goblet and Langerhans cells.51,242 Beneath conjunctival epithelium lies the conjunctival substantia propria, composed of a thin layer of loose connective tissue. Lymphocyte cell responses and antibody secretion by plasma cells in the conjunctival substantia propria are part of the eye’s normal defense mechanism.51

Worldwide, squamous cell papillomas of the conjunctiva are among the most common benign acquired epithelial lesions of the conjunctiva.4,90,171,206 These lesions most commonly have an exophytic (sessile or pedunculated) appearance, but may also have a mixed, or rarely an inverted, growth pattern.206 Lesions occur in children as well as adults, and are composed of multiple fronds, or finger-like projections of conjunctival epithelium that enclose cores of vascularized connective tissue.51 Despite rates of observed dysplastic changes in the lesions from 6-20%,146,206 carcinoma rarely develops in conjunctival papillomas. Although the literature is somewhat inconsistent concerning the most frequent location (bulbar vs tarsal),7,206 it has been noted that lesions tend to lie medially and inferiorly.206 Furthermore, large case series have demonstrated a greater prevalence of conjunctival papilloma among males.7,146,206

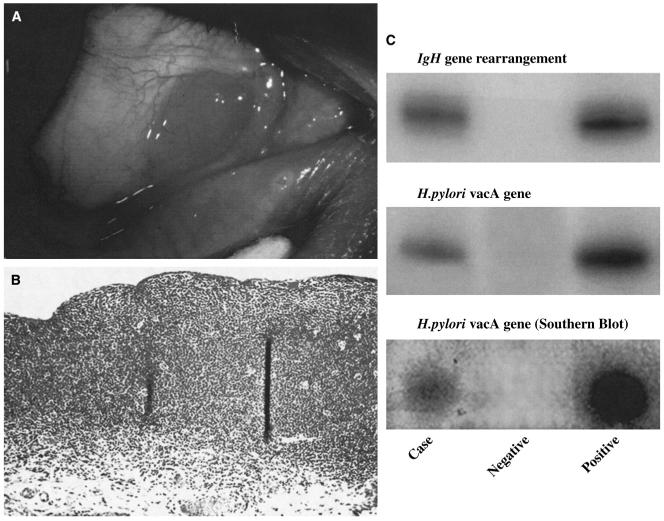

Even though conjunctival papilloma may persist for extended periods of time, with reported recurrence rates of 6-27%,7,146,206 the clinical course favors spontaneous regression and cure. In cases where large lesions (Fig. 1) cause symptoms or cosmetic defects, and periodic observation would be futile, surgery remains the treatment of choice with double freeze-thaw cryotherapy to the remaining conjunctiva to prevent tumor recurrence.203 Additionally, topical interferon alfa-2b45,124,157,194 and mitomycin C245 have been employed in the treatment of recurrent conjunctival papillomas.

Fig. 1.

Conjunctival papilloma. Clinical photograph of the lower tarsal conjunctiva showing a large papillary growth with multiple lobules, dilated telangietatic vessels, and edema.

2. Role of HPV in Conjunctival Papilloma

The presence of HPV in normal conjunctiva was examined in a study of 20 conjunctival biopsies taken from patients without conjunctival papilloma, and revealed that all were negative for evidence of HPV DNA.207 In stark contrast to this, investigations from Taiwan,54 Japan,189 the United States,148 and Denmark207,209 examining conjunctival papilloma biopsies for the presence of HPV using PCR amplification have revealed the presence of HPV DNA in 58-92% of all lesions. Biopsy specimens together with analysis of archival embedded tissue consistently reveal that the low-risk HPV types 6 and 11 are the most common types associated with conjunctival papilloma.7,148,207 Interestingly, these are the same types that are responsible for the majority of condyloma acuminata (genital warts) in men and women.27 The high-risk HPV types 16 and 18, as well as HPV types 33 (in an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS] patient) and 45 (one case) have also been documented in conjunctival papillomas.28,207 HPV types 16 and 18 are those commonly found in high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia103 and invasive cervical carcinoma.133

HPV encodes the E6 oncoprotein that acts upon p53,210 and the E7 oncoprotein which acts upon Rb,97 as well as increasing transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) promoter activity.180 TGF-β controls proliferation, differentiation, and other functions in most cell types. Compared to the highrisk HPV type 16 and type 18, the HPV type 6 E6 and E7 oncoproteins are seemingly less effective at transforming epithelial cells in vitro.89 This finding correlates with the fact that HPV types 6 and 11 are most frequently associated with the benign conjunctival papilloma, whereas the high risk HPV types 16 and 18 may be most frequently associated with conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasm (CIN)196 and conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma.159,217

The detection of HPV in conjunctival papillomas of infants whose mothers had documented genital HPV infection52,161 has led to speculation that the virus is acquired during birth, being transferred from the mother’s vagina to the newborn’s conjunctiva. In adults, the mechanism of infection may be self-inoculation. In undertaking a review of conjunctival papillomas for evidence of HPV infection, Sjö et al note that the incidence of conjunctival papilloma has a peak in younger patients (20-29 years).206 This is similar to the peak of genital HPV infection in women,99 and peak rates of genital HPV infections in men, where rates among 16-35 year olds are nearly 2.5 times higher than in older men.66 To analyze how digital self-inoculation may play a role, one need only examine the findings of a study that documented the presence of HPV DNA on the fingers of both male and female patients positive for genital HPV.211

Immunomodulatory agents such as topical interferon alpha and oral cimetidine have led to conjunctival papilloma regression.201 In addition to its apoptotic effect on tumor cells,222 interferon alpha exerts its antiviral action by preventing the replication of latent virus in the tissues.219 It is clear that HPV plays some role in a subset of conjunctival papillomas, yet unlike the case of cervical cancer, where HPV is a necessary cause of disease worldwide, the role of HPV in the etiology of conjunctival papilloma must be examined in light of host immune status.

B. CONJUNCTIVAL INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA AND CONJUNCTIVAL SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

1. Background

Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva is the most common malignancy of the conjunctiva.200 Clinically, the malignancy may appear identical to actinic keratosis:51 as leukoplakic lesions (white, shiny appearance caused by keratinization of the normally nonkeratinized conjunctival epithelium).242 Neoplastic changes to the conjunctiva occur on a spectrum of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia (grade 1 dysplasia through grade 3 carcinoma in situ). When a clonal population of neoplastic cells has infiltrated through the basement membrane and invaded into the substantia propria of the conjunctiva, this becomes squamous cell carcinoma.

The incidence of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma varies geographically (declining with greater distances from the equator), with Uganda having 1.2 cases per 100,000 persons per year, compared to the UK with fewer than 0.02 cases per 100,000 per year.166 In the USA, it is a rare disorder, with an incidence of 0.03 per 100,000 persons per year.215 There has been noted to be a higher incidence of 0.6 per 100,000 persons per year in Kampala, Uganda, which appears to be largely due to the epidemic of HIV infection.8 Multiple case series have noted a higher prevalence in male patients and the elderly,149,200,225 with the most frequently reported location being the limbus.149,203

Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma likely has a multifactorial etiology. Risk factors are believed to include fair skin pigmentation,200 ultraviolet radiation,166 human papillomavirus,79 atopic eczema,96,114 and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).78 It is known to have a high recurrence rate after excision alone, yet margin-free surgery remains the staple treatment. Cryotherapy, radiation, and chemotherapeutics have been used after excision to reduce recurrence rates. Topical mitomycin C,202 5-fluorouracil,151 and interferon alpha-2b224 have been successfully employed for recurrent lesions. One Australian study notes that mitomycin C is associated with relatively common side effects of allergic reaction and punctal stenosis.120 Limbal stem cell deficiency is a rare but important adverse effect of topical mitomycin treatment.59

Untreated invasive disease may spread to the globe or orbit, and warrant enucleation or exenteration.51 Intraocular invasion has been reported in 2-15% of all cases,56,149,225 and studies have found orbital invasion in 12-16% of cases.56,225 Metastases are rare, with the first site of extraocular involvement being regional lymph nodes. The frequency of lymph node metastases could not be assessed based on current studies. One case study of 287 patients from Mexico reports only two cases of regional metastasis.32

2. Role of HPV in Conjunctival Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Given the profound causal relationship between HPV and uterine cervical carcinoma, one would not be surprised to find this infectious microorganism playing a role in conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma. However, as multiple studies worldwide have failed to document an unequivocal association of HPV with conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma,54,167,227 the role of HPV remains unclear. Nonetheless, a few studies have captured an association with HPV type 16 or type 18,147,159,196 albeit at a far lesser frequency than that observed for HPV types 6 and 11 with conjunctival papilloma. What is surprising is that only one small study (n = 10) of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasm has demonstrated mRNA from the E6 region of HPV, which signals actively transcribed virus.196 Furthermore, this study from the United States demonstrated the lack of such mRNA from normal conjunctivas, whereas African case series have revealed a high prevalence of HPV DNA in clinically normal conjunctivas (HPV 6 and 11, but not HPV 16 and 18 were found).9 A recent study from Taiwan detected an association of cell-cycle regulatory protein, not HPV DNA, and conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma.111 Given the conflicting association studies, it appears that UV-B radiation plays a much greater role than HPV in the etiology of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma.

3. Role of HIV in Conjunctival Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma occur more frequently in AIDS patients, as is illustrated by its high prevalence in African population during the HIV pandemic.38,185 A strong association between HIV infection and conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma first emerged from studies in Rwanda, Malawi, and Uganda.172 A case series from Kenya documented a prevalence of 7.8% among HIV positive patients.38 Incidence of squamous cell carcinomas has been shown to be increasing in sub-Saharan African countries including Zimbabwe, where one study notes a nine-fold increase in cases over a 5-year period.39 Pola and colleagues in Zimbabwe reported an increase of prevalence of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma among tumors of the conjunctiva, increasing from 33% in 1996 to 57.9% in 2000; the prevalence was higher in women than men.184 A study from Uganda has reported that the incidence of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma has increased six-fold (from 6 per million cases per year to 35 per million cases per year) over a period of less than a decade.8 A case control study conducted in Uganda, using unconditional logistic regression, revealed that there was a 10-fold increased risk of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in HIV positive individuals (odds ratio 10.1, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.2-19.4, p < 0.001).167 Similarly, studies on patients with AIDS in the United States have also revealed an increased relative risk of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma.73 Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in HIV/AIDS patients presents on average at a younger age (35-40 years old) than in HIV-negative patients.223 Additionally, malignancy seems to be more aggressive in HIV/AIDS patients.112

It is unclear whether immunosuppression or HIV itself plays a role in this pathogenesis. Although there has been speculation that the role of HIV in conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma is through immunosuppression and activation of oncogenic viruses such as HPV in the conjunctiva, thus far only oral and anogenital HPV has been shown to occur more frequently in HIV-positive patients.11,30 Further studies are needed to confirm whether this is the case for conjunctival HPV infections. A review of autopsy cases in Uganda revealed no statistically significant evidence of increased conjunctival HPV infection in HIV/AIDS patients compared to controls (relative risk 1.3, 95% CI: 0.4-4.8).9 Immunosuppression itself may contribute to the carcinogenesis. Development of aggressive conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma has also been reported in an immunosuppressed liver transplant patient who received azathioprine and tacrolimus therapy.197 Another report documents two patients receiving long-term cyclosporine therapy developing conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia.134

Another possible mechanism for HIV in conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma is that it has been speculated in Kaposi sarcoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in AIDS patients, in which, in addition to downregulated cell-mediated immunity due to CD4 T-helper cell death, there is a pan-activation of the immune system (humoral) and an increase in cytokine release that leads to a chronic inflammatory state that facilitates malignant transformation.43 The chronic inflammatory process per se is able to provide a cytokine-based microenvironment, which could influence cell survival, growth, proliferation and migration, hence contributing to cancer initiation, progression, invasion, and metastasis. For example, oral lichen planus, being a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease, which has been clinically associated with development of oral squamous cell carcinoma.152,187

It is evident that conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma is increasing in developing nations, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Regardless of the exact HIV-related mechanism and the increased risk of infection in these areas, given the successes in the industrialized world of decreasing incidence of Kaposi sarcoma and lymphoma in patients treated with antiretroviral therapy,85 one hopes that such results would be seen in conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma if HIV medications were to become widely available in these regions. Currently, fewer than 1% of AIDS patients are receiving highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) in HIV-engulfed sub-Saharan Africa.144

C. CONJUNCTIVAL KAPOSI SARCOMA

1. Background

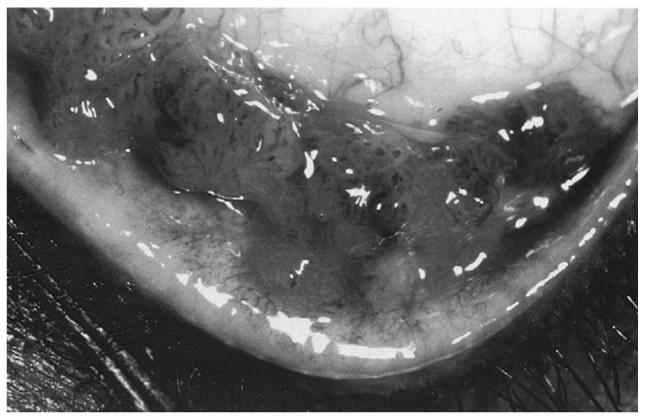

Kaposi sarcoma is a malignant vascular neoplasm, the classic form of which was originally reported as a local cutaneous disease in elderly men from the Mediterranean or Eastern European Jewish ancestry.107 The endemic form of the disease can be seen in Africa, where a high proportion of all cancer cases are Kaposi sarcoma. It affects skin, mucous membranes, internal organs, and lymph nodes.243 Histologically, it is composed of a matrix of endothelial lined vascular spaces surrounded by a population of clonal spindle cells of unknown origin (Fig. 2).10,25 Since the AIDS epidemic of the early 1980s, Kaposi sarcoma has been reported to be the most frequent malignant tumor in HIV/AIDS patients, especially among homosexual men in the USA.16,192 Prior to the AIDS epidemic, ocular involvement of Kaposi sarcoma was an extremely rare phenomenon, with fewer than 30 cases reported in the literature before 1982.113 Despite the decrease in number of AIDS patients who develop systemic Kaposi sarcoma in light of HAART, the proportion with Kaposi sarcoma that develop conjunctival lesions has remained stable at 5-10%.10

Fig. 2.

Conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma. Photomicrograph showing a vascular-like lesion composed of spindle-shaped cells resembling immature fibroblasts intermingled with vascular endothelial cells and small vascular lumens (hematoxylin & eosin, original magnification, ×200; insert, ×400).

The malignancy is of particular importance to ophthalmologists as conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma has been reported as the initial sole manifestation of HIV infection in a number of reports.41,123,195 It is also recognized as one of the most prominent features, similar to multiple opportunistic infections (such as cytomegalovirus [CMV] retinitis), of ocular complications in AIDS patients.102,174 In AIDS patients with Kaposi sarcoma, up to one in five may have some form of ocular involvement (conjunctiva, eye lids, or orbit).232,243

The lesion may be flat or raised and is bright red, painless, and surrounded by tortuous, dilated vessels.92 Conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma may be initially misdiagnosed as subconjunctival hemorrhage, but the localized elevation and lack of spontaneous resolution combined with biopsy will differentiate the lesions. Besides a surgical approach for treatment, regression of conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma is possible with radiation126,182 or with chemotherapy including bleomycin94 for ocular lesions that are accompanied by systemic Kaposi sarcoma.

2. Role of KSHV/HHV-8 in Conjunctival Kaposi Sarcoma

Herpes virus-like DNA sequences were first detected in the Kaposi sarcoma skin lesions of an AIDS patient,35 and subsequently also found in classic Kaposi lesions of Mediterranean patients,50 suggesting the possible role of a novel gamma herpesvirus. Since then, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) or human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) DNA has been identified in Kaposi sarcoma of both HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals, in locations such as skin,21,165 lymph node,168 lung,218 and oral mucosa.69 KSHV/HHV-8 has been identified also in Kaposi sarcoma of the eyelid in HIV-negative44 and HIV-positive226 patients. Despite the strong association of KSHV/HHV-8 with systemic Kaposi sarcoma, with evidence that up to 90% of all skin lesions contain KSHV/HHV-8 DNA,48 there are only a handful of studies that have examined the involvement of KSHV/HHV-8 in conjunctival or eyelid Kaposi sarcoma.92,154,195 A report from Japan on a HIV-positive homosexual male provides histological, DNA, and serological evidence of KSHV/HHV-8 in a case of bilateral conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma.154 This patient also had extensive oral, truncal, and pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma.

The infection route and pathogenesis of KSHV/HHV-8 are somewhat obscure, yet based on serological evidence of infection in homosexual men versus controls, sexual transmission of KSHV/HHV-8 has been postulated.118,141,173 The incidence of Kaposi sarcoma in homosexual men with AIDS is 20 times that in hemophilic AIDS patients.15 There are seemingly high co-infection rates of KSHV/HHV-8 with HIV. A report showed that anti-HHV-8 serum antibody was positive in 88% of an HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi Sarcoma group, and in 30% of an HIV-positive (without Kaposi sarcoma) group, compared to only 1-4% of a control group.75 Additionally, the KSHV/HHV-antibody titer of the sexually transmitted HIV group was markedly higher than that of the HIV group with other routes of infection (such as blood transfusion).118 Furthermore there is DNA evidence of high rates of KSHV/HHV-8 in the sperm as well as in the mononuclear cells of the semen of HIV-positive males.12,20

The existence of transmission modes other than sexual is likely. Serological and molecular evidence of a possible mechanism involving vertical mother-child transmission of KSHV/HHV-8 has been shown in Africa, where Kaposi sarcoma is endemic.137,143 Horizontal transmission of KSHV/HHV-8 has also been postulated, as a large study on classic Kaposi sarcoma in an Israeli population demonstrated infection rates of 95% or more as shown by serological evidence of KSHV/HHV-8.88 Kaposi sarcoma is most likely caused by multiple factors, including deregulated expression of oncogenes and oncosuppressor genes by KSHV/HHV-8 and, for AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma, the proliferative and angiogenic effects of the HIV-tat protein,18,55 combined with decreased immune surveillance and the release of cytokines and growth factors by HIV actions upon infected cells. The fact that KSVH/HHV-8 is not merely a passenger virus in tumors is convincingly demonstrated by a report that documents viral RNA in all dermal Kaposi sarcomas that were examined: from the earliest histologically recognizable stage to advanced tumors in which the vast majority of identifiable spindle tumor cells contained transcripts.193

KSHV/HHV-8 induces interleukin-6 (IL-6) during primary infection by modulating multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways.240 Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine secreted by many different cells including T-cells, macrophages, fibroblast, and RPE in response to trauma or pathogens. IL-6 induces STAT3 (signal transducers and activators of transcription 3) gene activation, thus driving oncogene expression.241,244 The exact influence of IL-6 on tumor cells remains unclear.

Although the exact mechanisms by which KSHV/HHV-8 mediates oncogenesis have not been fully elucidated, molecular biology studies have identified a number of KSHV/HHV-8 viral oncogenes that may contributed to neoplasia.156 Latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA), encoded by the KSHV/HHV-8 genome, is a protein shown to be consistently expressed in latently infected cells of skin lesions. LANA acts as a transcriptional regulator, interacting with the tumor suppressor genes p53 and Rb, thus providing a mechanism whereby it may promote oncogenesis.205 LANA competes with E2F (E2 transcription factor) for binding of hypophosphorylated pRb (retinoblastoma protein), thus freeing E2F to activate gene transcription involved in cell cycle progression. Additionally, LANA inhibits p53, thus allowing latent KSHV/HHV-8 to promote cell cycle progression while inhibiting apoptosis.186 Viral mRNA for the latent state LANA (latency-associated nuclear antigen), vCYC-D (viral cyclin D), and vFLIP (viral Fas-associated death domain-like IL-1 -converting enzyme inhibitory protein) genes are found consistently in spindle cells of skin lesions.119,213 The viral encoded protein vFLIP inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis,87 as well as activating NF-κB.5 Expression studies in conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma remain to be undertaken.

III. Chronic Antigen Stimulation, Infectious Agents, and Ocular Adnexal Neoplasia

A. MALT LYMPHOMAS OF THE OCULAR ADNEXA

1. Background

Lymphomas arising outside of lymph nodes or spleen are categorized as extranodal. One to two percent of all lymphomas13 and up to 8% of extranodal lymphomas72 arise in the ocular adnexa, including conjunctiva, eyelid, lacrimal gland, and orbit. A subset of these are ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas. The term MALT lymphoma denotes a characteristic arrangement of lymphoid tissue found in certain mucosal surfaces,106 having distinct features from other forms of primary non-Hodgkin extranodal lymphoma. Although the majority of literature does not separate ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma by site of origin, in order of decreasing frequency involvement it is seen in the orbit, conjunctiva, and lacrimal gland.67 Ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma is primarily a disease of older adults, and is slightly more prevalent in women.67,71,169,234 This section will focus on conjunctival and orbital MALT lymphoma as the majority of research in the literature has focused on a possible role of infectious agents in MALT-type lymphomas.

a. Conjunctival MALT Lymphoma

Primary lymphomas of the conjunctiva are rare. Many of those in the conjunctiva are a discrete clinicopathologic entity of the marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the MALT type, a low-grade non-Hodgkin B cell tumor with good prognosis.203

There has been much controversy surrounding the defense mechanisms of the conjunctiva, and whether MALT exists in normal human conjunctiva. It is now clear that conjunctiva contains this lymphoid tissue. By examining the complete conjunctival sacs of 53 cadaveric eyes, Knop and Knop discovered that human conjunctiva includes an organized associated lymphoid tissue that consists of all components necessary for a complete immune response.121 Consistent with previously reported work,236 and in light of the fact that the amount of conjunctival MALT and the differential composition of the lymphoid components may vary between individuals, the authors suggested that the presence of conjunctival MALT is related to antigenic stimuli which are inevitable during life.

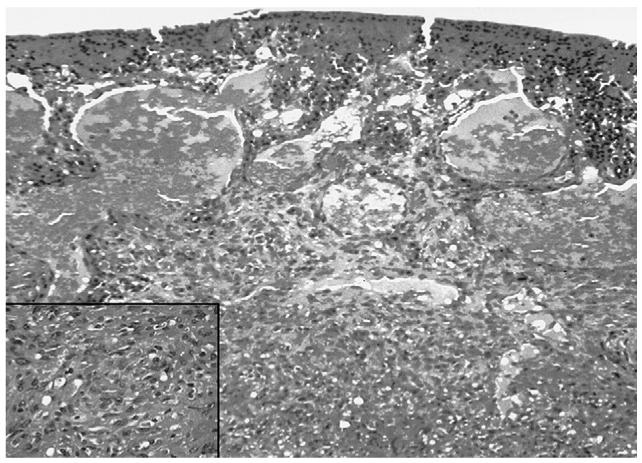

Clinically, conjunctival MALT lymphomas may cause few symptoms because the neoplastic lymphocyte population lacks a connective tissue stroma and is able to mold to surrounding tissue without causing much irritation.51 The disease follows an indolent course and mostly remains localized to the conjunctiva. Rarely, associated intraocular involvement has been described.100,191 The vascularity of tumors is reflected by the characteristic salmon pink color (Fig. 3A). In a large case series, Shields et al documented that conjunctival lymphoid tumors are generally hidden under the eyelid in the midbulbar conjunctiva or in the fornix, rather than at the more obvious limbal location, and hence eyelid elevation and ocular rotation at the slit-lamp are instrumental in tumor visualization.204 Biopsy is necessary to establish the diagnosis as it is clinically difficult to differentiate between a benign inflammation and malignant lymphoid tumor, and a systemic evaluation should be performed in all affected patients to exclude the presence of systemic lymphoma.203 While isolated conjunctival MALT lymphoma is most often treated with external beam irradiation,229,239 care must be taken to avoid complications such as xerophthalmia, keratitis, cataract formation, and retinal damage. A few case series have demonstrated that careful observation following biopsy may result in no inferior clinical outcomes or decreased survival.142,220 Cryotherapy53 and local interferon alpha19 have been shown to be as effective as radiation with lower side-effects, although in smaller case series. Recently, consistent with its effectiveness in other non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas, at least one study has documented the efficacy of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in causing tumor remission in two cases of relapsed conjunctival MALT lymphoma.170

Fig. 3.

Conjunctival MALT lymphoma. A: Clinical photograph of a slight raised, salmon pink-colored, nasal bulbar conjunctival lesion in the right eye. B: Photomicrograph showing diffuse monotonous lymphoid cellular infiltration in the substantia propria with invasion to conjunctival epithelia (hematoxylin & eosin, original magnification, ×50) C: Gels of PCR analyses of the microdissected, conjunctival lymphoid cells showing positive IgH gene rearrangment and H. pylori genes.

Sjö and colleagues made the interesting observation that the clinical course of conjunctival MALT lymphoma, including frequent bilateral presentation and spontaneous remission, signals an infectious etiology, resulting from bilateral infection and clearance of antigen, respectively.208 Furthermore, multiple reports have noted conjunctival MALT lymphoma masquerading as conjunctivitis3,117,127 in patients having a prior history of conjunctivitis, possibly due to the chronic inflammation and the role that a chronic antigen stimulating mechanism may play in oncogenesis. The two putative organisms that may contribute to the pathogenesis of conjunctival MALT lymphoma are H. pylori and Chlamydia psittaci (C. psittaci). Due to the majority of the literature not separating conjunctival MALT lymphoma from other ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas, the role of C. psittaci will be examined in the context of its role in ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas overall.

b. Orbital MALT Lymphoma

Lymphoid neoplasms are the most frequent primary malignant neoplasms of the orbit,140 accounting for approximately 10% of all orbital neoplasms,243 and, as in the conjunctiva, extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the MALT type constitutes the most common form.64 Clinical presentation is characterized by a slow painless onset, which often results in a long interval between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis. The clinical course is usually indolent and localized to the orbit.234 Absence of lymphatic drainage channels in the region may explain why malignancies remain localized to the orbit.76 The putative organisms that may play roles in the etiology of orbital MALT lymphoma are Chlamydia (C. Psittaci and C. Pneumoniae) and Hepatitis C.

Differential diagnoses to consider with orbital MALT lymphoma include inflammatory responses of the orbit, benign lymphoproliferations, systemic metastatic lymphoma, and other orbital neoplasms. Biopsy is essential to diagnosis (Fig. 3B). Management of patients with ocular adnexal lymphomas should include a thorough systemic medical examination to establish the clinical stage of the disease. Radiotherapy has proven very effective for local disease,229 and chemotherapy for disseminated disease. 128Combined therapy has been associated with lower relapse rates.37

c. Chronic Antigen Stimulation in Ocular Adnexal MALT Lymphoma

MALT lymphomas arise at sites of chronic antigenic stimulation214 due to autoimmunity (e.g., Sjögren sialoadenitis248 and Hashimoto thyroiditis105) or infections (such as H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis237). Antigens from infectious agents play a growth-sustaining role; this is supported by the observation that a proportion of gastric MALT lymphomas are curable by eradication of the infectious agent.57 Sequence analysis of immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable genes in neoplastic cells of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma reveal that a chronic inflammatory mechanism may be involved in the lymphomagenesis, as the clonal mutation patterns indicate that antigen-driven selection occurred during development of post-germinal-center memory B-cells.40,91,138 The chronic antigen stimulation hypothesis holds that a specific infectious agent initiates a reactive lymphoid infiltrate in the normally sterile ocular adnexal tissues. This ultimately leads to a B-cell clonal expansion and proliferation. At this stage, genetic alterations and microenvironment may sustain the growth independent of the infectious agent. NF-κB is a nuclear transcription factor, found in lymphoid cells of both B- and T-cell lineage, involved in inflammation and immune response. It is the common pathway for tumor cell activation, and has an anti-apoptotic function. Aberrant NF-κB activation in tumor cells results from genetic changes or the activation of NF-κB pathways by antigen mechanisms.116 Lymphoma cell lines with constitutively active NF-κB were found to be resistant to inducers of the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways, with several NF-κB target genes being overexpressed, including Bcl-xL, Fas-associated death domain-like IL-1beta-converting enzyme inhibitor protein, cellular inhibitor of apoptosis, and X inhibitor of apoptosis.17

Additionally, the role of infectious agents is inferred from the fact that ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas share clinicopathologic features with gastric MALT lymphomas, for which the central etiological role of H. pylori has been firmly established. Both ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas and gastric MALT lymphomas are characterized by an indolent course, a large prevalence of marginal zone B-cell histologic type, and a varying degree of infiltrating reactive T-cells.29 The role of an infectious agent may further be elucidated by National Cancer Institute data that depict a rapid and steadily increasing incidence of ocular non-Hodgkin lymphomas from 1975-2001 (both intraocular and adnexal) in white men and women, with no evidence of peaking in recent years.158 This is in distinct contrast to non-ophthalmic non-Hodgkin lymphomas, the incidence of which showed evidence of peaking in recent years.

2. Role of H. pylori in Conjunctival MALT Lymphoma

H. pylori is a spiral-shaped Gram-negative bacteria that infects a large proportion of the population worldwide. In developing countries up to 70-90% of the population is infected (primarily during childhood), whereas in developed countries the prevalence of infection is lower, at 25-50%.49 In most cases the organism causes no symptoms in the host, yet it has been recognized as the cause of duodenal ulcers and gastric adenocarcinoma, and can be found in greater than 90% of gastric MALT lymphomas.237 H. pylori evades host adaptive and innate responses by frequent antigenic variation, and host antigen mimicry.101 The host immune and inflammatory responses increase cellular damage and turnover, thereby promoting carcinogenesis.70,155,214 Most patients who have H. pylori infection never develop lymphoma, likely due to other oncogenetic factors, such as host response. Recent studies have shown an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in patients affected by polymorphisms in different loci of inflammatory cytokines.129,130,246 It remains to be seen if such host genetic factors also play a role in susceptibility to conjunctival MALT lymphoma.

Whereas eradication of the H. pylori leads to regression of early gastric MALT lymphoma in up to 80% of cases,221,235 no literature was found on the effect of possible eradication of conjunctival H. pylori infection on conjunctival MALT lymphoma lesions. The only study assessing treatment against this organism was conducted by Ferreri et al in Italy to assess rates of H. pylori gastric infection in patients with ocular adnexal lymphoma.64 Of note, the study did not in fact examine H. pylori or its DNA in conjunctival MALT lymphoma lesions. Out of the 31 patients with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma, 10 (32%) had gastric H. pylori, and 4 were treated with H. pylori eradicating antibiotics exclusively (erythromycin 500 mg twice a day, omeprazole 20 mg twice a day, and tinidazole 500 mg twice a day, for 7 days). The ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma in these patients showed no response, six received H. pylori eradicating antibiotics concurrently with other therapies (doxycycline, rituximab, or orbit irradiation) achieving lymphoma regression in all cases. Interestingly, three of the patients who were positive for gastric H. pylori infection had C. psittaci-positive conjunctival MALT lymphomas. Treatment with H. pylori-eradicating antibiotics led to no measurable conjunctival lymphoma regression in all three patients. Although this may raise doubts about the putative role of H. pylori in sustaining the growth of this MALT lymphoma, it may also simply highlight the sensitivity of organisms to the specific antibiotics used. Furthermore, clearance of peripheral H. pylori may not amount to clearance of conjunctival H. pylori, particularly components of the bacterial genome. Finally, it may be simply as the authors describe: that the pathogenetic role of another microorganism, likely C. psittaci, is more relevant than those played by H. pylori.

Given the high prevalence of H. pylori infection and its importance in the etiology of gastric MALT lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma, surprisingly few studies have looked at the role of this organism in conjunctival MALT lymphoma. A study on cases from France and the USA reported that in four of five cases of conjunctival MALT lymphoma, lesions contained PCR and Southern hybridization evidence of H. pylori DNA, while the surrounding normal conjunctiva showed no evidence of H. pylori (Fig. 3C).34 The French patient with positive H. pylori gene also had positive H. pylori serum titer, a gastric lesion, and orbital MALT lymphoma.33 In contrast to this, a retrospective case series from Denmark of 13 patients reports no evidence of H. pylori using immunohistochemistry or PCR in conjunctival MALT lymphoma lesions or in controls (conjunctival lymphoid hyperplasia or normal conjunctival areas).208 Similarly, a German study of 47 samples of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma (with 22 extranodal mantle zone lymphomas, 9 follicular lymphomas, 3 mantle cell lymphomas, 3 diffuse large cell B-cell lymphomas, 2 immunocytomas, and 1 small cell B-lymphocytic lymphoma) revealed no evidence of H. pylori based on PCR.81 An obvious shortcoming of this study as pointed out by the authors was that about half the samples failed to display beta-globin, a housekeeping gene, and hence DNA was likely degraded or crosslinked. Nonetheless, the theory that contradictory results are due to geographic variation of the pathogenic organism, akin to that of the conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma and HPV experience, is not an unlikely explanation. In fact, genotypes of HPV differ worldwide, with certain virulence genes, such as vacA and cagA, being more prevalent in parts of the world that have a higher rate of gastric adenocarcinoma.190,230 The same fact may hold true with conjunctival MALT lymphoma. Large epidemiological studies remain difficult to conduct as conjunctival MALT lymphoma is such a rare disease.

Further studies are imperative before H. pylori can be implicated as playing a significant role in the etiology of conjunctival MALT lymphoma. The field lags behind that of the study of H. pylori association with other non-Hodgkin lymphomas. No studies were identified that have examined whether H. pylori associated conjunctival lesions display increased cytokines, such as TNF-alpha or IL-6, which would support a possible chronic antigen stimulation-inflammation mechanism, as has been the case in gastric MALT lymphoma lesions. Furthermore, studies are lacking in assessing the presence of H. pylori in the normal conjunctiva worldwide.

3. Role of Chlamydia in Ocular Adnexal MALT Lymphoma

Chlamydia are obligate intracellular bacteria with a unique biphasic life cycle. Elementary bodies facilitate transit between cells, and metabolically active reticulate bodies are responsible for intracellular replication. Although the typical ocular involvement is by the sexually transmitted C. trachomatis, characterized by the development of follicles and inflamed conjunctivae, it is now evident that other species including C. psittaci and C. pneumoniae may be of great interest to ophthalmologists. All chlamydial species have a tendency to cause persistent infections that may play a role in oncogenesis.

C. pneumoniae is a widespread pathogen, a common cause of pulmonary infection, with serum positivity in at least 50% of the general population.77 Chronic infections by C. pneumoniae are associated with lung cancer122,132 and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 It is a potent inducer of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in human monocytic cells,95 which may be important to pathogenesis as monocytes are believed to be carriers of the infection to other sites in the body. The first report on the possible association between C. pneumoniae and ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma came from Shen and colleagues, reporting on a patient from Hong Kong with bilateral orbital MALT lymphoma. The molecular signature of C. pneumoniae, but not C. psittaci, was identified in biopsy of the lesion.198 Additional reports of C. pneumoniae involvement in the literature combine findings with an analysis of possible C. psittaci involvement, and hence will be discussed herein.

C. psittaci is best known as the etiologic agent of psittacosis, a human infection marked by an atypical pneumonia with symptoms of fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, and a dry cough, caused by exposure to excretions from infected birds.93 Additionally, C. psittaci has been isolated in secretions of infected cats,216 likely serving as an additional source of human infection.

In 2004, a significant association between ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma and C. psittaci was reported by Ferreri and colleagues in Italy.60 A study of 40 ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma samples showed that 32 samples (80% of patients) carried C. psittaci DNA in the lesion, and all lymphoma samples were negative for C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae. In the control groups, none of the 20 nonneoplastic orbital biopsies showed evidence of C. psittaci DNA, whereas 3 of 26 (12%) reactive lymphadenopathy samples were positive for C. psittaci DNA. In addition to tumor biopsies, a number of blood samples were taken from patients with chlamydia-positive lymphoma, and found that 9 of 21 (43%) carried C. psittaci DNA in their peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), whereas none of the healthy PBMC donors carried C. psittaci DNA. Similar to findings in the tumors, DNA sequences from C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis were not detected in PBMC samples from lymphoma case patients. The significance of C. psittaci DNA in PBMCs has been related to a state of persistent infection and possible reactivation and chronic antigen stimulation.

Similar to other putative infectious agents that play a role in oncogenesis discussed in this review, both C. pneumoniae and C. psittaci seemingly also exhibit geographic variation and hence the significance of these infectious agents in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma remains uncertain. With respect to C. pneumoniae, the positive associations reported in studies were in patients from Hong Kong and the UK, Germany, and southern China.36,198 Patients from both of the studies conducted by Ferreri that failed to document evidence of C. pneumoniae were from Italy and Hungary. When one examines the C. psittaci story, many studies refute the findings of Ferreri and colleagues in an Italian cohort. Although a study on eight ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas in France found no evidence of C. psittaci in any of the samples, there was evidence in one case of follicular lymphoma.46 A recent study of 26 cases of ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas from Cuba revealed only two cases positive for C. psittaci DNA while all 20 benign ocular lesions were negative for C. psittaci.82 An even more dramatic example, contradicting the findings of Ferreri, can be found in a study conducted on a cohort from south Florida (57 tumor specimens) that found no cases of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma specimens harbored C. psittaci DNA.188 Similarly, studies from the Netherlands160 (38 patients), Japan (18 patients),42 Germany (47 cases of ocular adnexal lymphoma, 22 of which were MALT lymphoma type),81 and northeastern United States (7 patients)231 have failed to document any evidence of C. psittaci in lesions of the ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma.

In light of these conflicting results, Chanudet and colleagues designed a study in which 142 ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas from six geographical regions were investigated for evidence of C. psittaci. Although the overall prevalence of C. psittaci in MALT lymphomas was 22% (31 out of 142 cases), and statistically significantly higher than in controls, C. psittaci was also found in a number of biopsy specimens of orbital non-lymphoproliferative diseases (10%, p = 0.042) and non-marginal zone lymphoma cases (9%, p = 0.033).36 The presence of C. psittaci in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma showed marked variation among the six geographical regions examined, being most frequent in Germany (47%), followed by the USA (35%) and the Netherlands (29%), but relatively low in Italy (13%), the UK (12%), and southern China (11%). Additionally, 17 from 127 (13%) cases of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma from all six regions showed evidence of C. pneumoniae DNA. The 17 positive cases were from the UK, Germany, and southern China, whereas cases from Italy, the Netherlands, and the United States demonstrated no evidence of C. pneumoniae. Only cases from southern China displayed a trend toward a higher prevalence of C. pneumoniae in MALT lymphomas than in non-lymphoproliferative disease and non-MALT lymphoma cases from the same region, but these differences were not statistically significant. In fact, overall, the prevalence of C. pneumoniae was higher in non-MALT lymphoma samples than in MALT lymphoma samples, 24% vs 13%.

In a pilot study, Ferreri and colleagues showed that treatment with doxycycline (100 mg twice a day for 3 weeks) resulted in lymphoma regression in seven of nine patients with C. psittaci-related ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma.62 Lending support to the chronic antigen-driven lymphogenesis theory, five of the patients had reported prolonged contacts with household animals, and seven patients had a history of chronic conjunctivitis. In a follow-up multicenter trial with doxycycline on patients with both C. psittaci-positive and C. psittaci-negative ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma, regression was observed in 7 of 11 C. psittaci-positive patients and 6 of 16 C. psittaci-negative patients.63 It is interesting to note that none of the 27 patients with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma were found to be positive for C. pneumoniae DNA.63 Based on the fact that even C. psittaci-negative lesions regressed with treatment, the authors hypothesize that other undiscovered doxycycline-sensitive organisms may also be involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. Furthermore, the authors highlight the need to develop more sensitive methods for C. psittaci detection. The key finding of the study was that response to antibiotics was slow, with up to a third of responders not achieving best outcome until after 1-year follow up, after only 3 weeks of antibiotic treatment.

Despite the seemingly promising results of treatment with doxycycline described herein, the question remains whether all patients with ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas should be treated for a possible infectious etiology. Two studies on patients with ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas who had not been assessed for the presence of C. psittaci in lesions provide conflicting results. The first study from Austria had a median follow-up of 9 months86 and revealed that 11 patients were given daily doxycycline 200 mg orally over 3 weeks, and none of the patients had an objectively measureable response. However, a study from the United States of three patients with conjunctival MALT lymphoma revealed that two patients had a complete remission (42 months follow-up) and the other patient had a partial remission (18 months follow-up).2 The small sample sizes of these studies is an obvious caution, but one that is not easily addressed given the rarity of ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas. Varied results of treatment with antibiotics might be attributable to geographic variation of the putative infectious agents, different genetic background of the patients with MALT lymphomas, and also by their sensitivity to the antibiotics that were selected for treatment.

4. Role of Hepatitis C in Ocular Adnexal MALT Lymphoma

Hepatitis C is a blood borne infectious viral disease that is caused by HCV, an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus. The virus is best known for its ability to cause inflammation of the liver, with chronic infection resulting in cirrhosis and liver cancer. Additionally, it is known as the cause of mixed cryoglobulinemia, a benign B-cell proliferative disorder with clonal expansion of distinct B-cells that can eventually turn into frank B-cell malignancy.

Those with a history of intravenous drug use, tattoos, or those who have been exposed to blood via unsafe sex or other unsafe practices are at higher risk. The natural course of disease varies between individuals, with a subset of patients developing cirrhosis, and an even smaller number developing liver cancer. In patients with chronic hepatitis C infection, optimal treatment involves a combination of peginterferon alfa-2b (interferon with the addition of a polyethylene glycol [PEG] polymer) and ribavirin.139 Most recently, Ferreri and colleagues reported an association with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma.65 There is increasing molecular and epidemiological evidence of the pathogenesis of hepatitis C-associated lymphoma. Patients infected with HCV have been shown to have increased risk of developing B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, particularly with an extranodal localization in the liver, spleen, and salivary glands.47

The potential mechanisms of HCV-induced oncogenesis have been best studied in hepatocellular carcinoma. The virus lacks reverse transcriptase, and hence is unable to integrate into the host genome, and it does not encode for any known oncogenes.228 However, there is increasing evidence that HCV-encoded proteins may contribute to oncogenesis by interfering with signal transduction, growth regulation and apoptosis. For example, HCV core protein has been shown to transform mouse fibroblast cells in vitro, and additionally, similar to KSHV/HHV-8, shown to induce the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6.58 In addition to HCV core protein, the HCV E2 envelope protein has been identified as a potential antigen that may drive the development of lymphoma.135 HCV infection becomes chronic in a number of cases, and actively replicating virus has been demonstrated in HCV-associated lymphomas. Furthermore, there is a high incidence of circulating monoclonal B-cells, as evidenced by populations of lymphocytes expressing the same immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) rearrangements.

Ferreri and colleagues analyzed 55 patients from Italy with ocular adnexal lymphoma of MALT-type, and reported that 7 patients (13%) had HCV seropositivity. Furthermore, the authors claimed that HCV seropositivity is associated with more disseminated disease and aggressive behavior.65 It is important to note that unlike in their previous studies on the association between ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma and C. psittaci, lesions were not biopsied to examine for molecular evidence of the infectious agent. Arnaud and colleagues from France, in examining 40 patients with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma, found only 1 patient to be seropositive for HCV.6 The authors note that this finding, combined with the fact that no efficacy of antiretroviral therapy has yet to be reported for HCV-positive ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma, rules out HCV as critical in oncogenesis. As in the Ferreri study, the Arnaud study neglected to examine for HCV RNA in lesions.

Geographic variation in prevalence of HCV infection undoubtedly plays a role in these discrepancies in findings. HCV appears to be associated with B-cell lymphomas mainly in areas where the infection is highly prevalent in the general population. HCV infection is seen to be more prevalent in Italy, thus supporting Ferreri’s findings (1.15% in France versus 3% in Italy). Studies have documented a higher prevalence of HCV seropositivity in patients with B-cell lymphomas (15%), as compared to HCV seropositivity in healthy patients (1.5%) and compared to patients with other hematological malignancies (2.9%).80 Further studies are needed before HCV can be considered to play an important etiologic role in ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas. Future studies should include an analysis of HCV RNA in lesions, as seropositivity may merely reflect geographic differences in prevalence of HCV.

IV. Anti-infectious Therapy

Whereas many studies in the literature describe putative infectious agents and their role in ocular adnexal neoplasia, few have adequately addressed an anti-infectious approach. Given the fact that other risk factors may play a greater role in the etiology of these neoplasms, combined with the vast geographic variation in putative infectious organisms, and the varying sensitivities of the putative microorganisms to different anti-infectious treatments, it is premature and unwarranted to recommend such therapy be added to the standard of care (surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy). In other areas of medicine perhaps the best illustration of a change in treatment that is now directed towards an infectious agent, is in early stage gastric MALT lymphoma, which completely regresses with antibiotics targeting H. pylori. Similarly, long-term follow-up of the recombinant HPV vaccine will undoubtedly demonstrate the results of targeting this infectious agent on cervical cancer incidence. Randomized controlled trials are needed before anti-infectious therapy can be considered standard clinical practice when approaching ocular adnexal neoplasia.

V. Summary

The etiological role of infectious agents in certain human cancers has been firmly established. In cervical cancer, HPV has been identified in greater than 99% of lesions. Similarly, H. pylori is seen to play an important role in the pathogenesis of both gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric MALT lymphoma, while chronic infection with hepatitis B is seen to lead to hepatocellular carcimona. The role of infectious agents in the etiology of ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas is less clear. Although the literature offers a rich list of putative organisms causing neoplasms, ranging from conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma to ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma, it seems that other risk factors, including genetic and environmental, host and microorganism, may play a greater role in the pathogenesis of many of these neoplasms. Nonetheless, the impact on anti-infectious treatment and prevention may one day be seen in certain ocular adnexal neoplasms. Already, Ferreri and colleagues from Italy have demonstrated promising results of doxycycline therapy in C. psittaci-associated ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas. A welcome, though unexpected, finding in their studies was that a portion of C. psittaci negative lesions responded to treatment with antibiotics, perhaps signaling a yet undiscovered pathogen in these neoplasms. However, one cannot exclude the possibility that an insufficient detection method for C. psittaci itself could explain these findings.

VI. Method of Literature Search

The literature was searched on the Medline database, using the Pubmed interface including literature from the years 1950-2007. The search strategy included MeSH and natural language terms to retrieve references on conjunctival papilloma, conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma, conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma, ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma, infectious oncogenes, and chronic antigen stimulation in oncogenesis. Due to the fact that many large clinical controlled trials were not available, small patient series and relevant case reports were also included. For foreign language publications, no translation was obtained, however the abstracts of non-English articles found to be of particular relevance to the review were utilized. Reference lists in retrieved articles, and textbooks, were also searched for relevant references.

Acknowledgments

The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article. The authors wish to thank all members of the Immunopathology Section, Laboratory of Immunology at the National Eye Institute, for their perpetual support. The NEI Intramural Research Program provides research support.

References

- 1.Abrams JT, Balin BJ, Vonderheid EC. Association between Sézary T cell-activating factor, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;941:69–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramson DH, Rollins I, Coleman M. Periocular mucosa-associated lymphoid/low grade lymphomas: treatment with antibiotics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:729–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akpek EK, Polcharoen W, Ferry JA, et al. Conjunctival lymphoma masquerading as chronic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:757–60. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amoli FA, Heidari AB. Survey of 447 patients with conjunctival neoplastic lesions in Farabi Eye Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006;13:275–9. doi: 10.1080/09286580600801036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An J, Sun Y, Sun R, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encoded vFLIP induces cellular IL-6 expression: the role of the NF-kappaB and JNK/AP1 pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:3371–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnaud P, Escande MC, Lecuit M, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and MALT-type ocular adnexal lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:400–1. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl369. author reply 401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ash JE. Epibulbar tumors. Am J Ophthalmol. 1950;33:1203–19. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(50)90990-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ateenyi-Agaba C. Conjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma associated with HIV infection in Kampala, Uganda. Lancet. 1995;345:695–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90870-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ateenyi-Agaba C, Weiderpass E, Tommasino M, et al. Papillomavirus infection in the conjunctiva of individuals with and without AIDS: an autopsy series from Uganda. Cancer Lett. 2006;239:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Augsburger JJ, Schneider S. Tumors of the Conjunctiva and Cornea. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, editors. Ophthalmology. 2 Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 2004. pp. 535–45. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aynaud O, Piron D, Barrasso R, et al. Comparison of clinical, histological, and virological symptoms of HPV in HIV-1 infected men and immunocompetent subjects. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74:32–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.74.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagasra O, Patel D, Bobroski L, et al. Localization of human herpesvirus type 8 in human sperms by in situ PCR. J Mol Histol. 2005;36:401–12. doi: 10.1007/s10735-005-9010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bairey O, Kremer I, Rakowsky E, et al. Orbital and adnexal involvement in systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer. 1994;73:2395–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940501)73:9<2395::aid-cncr2820730924>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayerdörffer E, Neubauer A, Rudolph B, et al. MALT Lymphoma Study Group Regression of primary gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Lancet. 1995;345:1591–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beral V, Bull D, Darby S, et al. Risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma and sexual practices associated with faecal contact in homosexual or bisexual men with AIDS. Lancet. 1992;339:632–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90793-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, Jaffe HW. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90001-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernal-Mizrachi L, Lovly CM, Ratner L. The role of NF-{kappa}B-1 and NF-{kappa}B-2-mediated resistance to apoptosis in lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9220–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507809103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biberfeld P, Ensoli B, Stürzl M, et al. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8, cytokines, growth factors and HIV in pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1998;11:97–105. doi: 10.1097/00001432-199804000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blasi MA, Gherlinzoni F, Calvisi G, et al. Local chemotherapy with interferon-alpha for conjunctival mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: a preliminary report. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:559–62. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00591-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bobroski L, Bagasra AU, Patel D, et al. Localization of human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8) in the Kaposi’s sarcoma tissues and the semen specimens of HIV-1 infected and uninfected individuals by utilizing in situ polymerase chain reaction. J Reprod Immunol. 1998;41:149–60. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(98)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boneschi V, Brambilla L, Berti E, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 DNA in the skin and blood of patients with Mediterranean Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinical correlations. Dermatology. 2001;203:19–23. doi: 10.1159/000051697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bos TJ. Oncogenes and cell growth. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;321:45–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3448-8_6. discussion 51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Muñoz N, et al. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:244–65. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosch FX, Manos MM, Muñoz N, et al. International biological study on cervical cancer (IBSCC) Study Group Prevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:796–802. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.11.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boshoff C, Schulz TF, Kennedy MM, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infects endothelial and spindle cells. Nat Med. 1995;1:1274–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourgault-Villada I. Anti human-papillomavirus vaccines: concepts, aims and trials. Rev Med Interne. 2007;28:22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown DR, Schroeder JM, Bryan JT, et al. Detection of multiple human papillomavirus types in Condylomata acuminata lesions from otherwise healthy and immunosuppressed patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3316–22. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3316-3322.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buggage RR, Smith JA, Shen D, et al. Conjunctival papillomas caused by human papillomavirus type 33. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:202–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cahill M, Barnes C, Moriarty P, et al. Ocular adnexal lymphoma-comparison of MALT lymphoma with other histological types. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:742–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cameron JE, Hagensee ME. Human papillomavirus infection and disease in the HIV+ individual. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;133:185–213. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46816-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell RJ. Histological Typing of Tumours of the Eye and its Adnexa. Springer; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cervantes G, Rodríguez AA, Leal AG. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: clinicopathological features in 287 cases. Can J Ophthalmol. 2002;37:14–9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(02)80093-x. discussion 19-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan CC, Shen DF, Mochizuki M, et al. Detection of Helicobacter Pylori and Chlamydia Pneumoniae Genes in Primary Orbital Lymphoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;104:62–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan CC, Smith JA, Shen DF, et al. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) molecular signature in conjunctival mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Histol Histopathol. 2004;19:1219–26. doi: 10.14670/hh-19.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kapo-si’s sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chanudet E, Zhou Y, Bacon CM, et al. Chlamydia psittaci is variably associated with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma in different geographical regions. J Pathol. 2006;209:344–51. doi: 10.1002/path.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charlotte F, Doghmi K, Cassoux N, et al. Ocular adnexal marginal zone B cell lymphoma: a clinical and pathologic study of 23 cases. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:506–16. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chisi SK, Kollmann MK, Karimurio J. Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection seen at two hospitals in Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2006;83:267–70. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v83i5.9432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chokunonga E, Levy LM, Bassett MT, et al. Aids and cancer in Africa: the evolving epidemic in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 1999;13:2583–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912240-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coupland SE, Foss HD, Anagnostopoulos I, et al. Immunoglobulin VH gene expression among extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of the ocular adnexa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:555–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis TH, Durairaj VD. Conjunctival Kaposi sarcoma as the initial presentation of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:314–5. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000167783.06103.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daibata M, Nemoto Y, Togitani K, et al. Absence of Chlamydia psittaci in ocular adnexal lymphoma from Japanese patients. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:651–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalgleish AG, O’Byrne KJ. Chronic immune activation and inflammation in the pathogenesis of AIDS and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2002;84:231–76. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(02)84008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dammacco R, Lapenna L, Giancipoli G, et al. Solitary eyelid Kaposi sarcoma in an HIV-negative patient. Cornea. 2006;25:490–2. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000214212.37447.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Keizer RJ, de Wolff-Rouendaal D. Topical alpha-interferon in recurrent conjunctival papilloma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81:193–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Cremoux P, Subtil A, Ferreri AJ, et al. Re: Evidence for an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:365–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Vita S, Sacco C, Sansonno D, et al. Characterization of overt B-cell lymphomas in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Blood. 1997;90:776–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dictor M, Rambech E, Way D, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus) DNA in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions, AIDS Kaposi’s sarcoma cell lines, endothelial Kaposi’s sarcoma simulators, and the skin of immunosuppressed patients. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:2009–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:720–41. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dupin N, Grandadam M, Calvez V, et al. Herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in patients with Mediterranean Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet. 1995;345:761–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eagle RC. Eye Pathology: An Atlas and Basic Text. WB Saunders Co; Philadelphia: 1999. pp. 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Egbert JE, Kersten RC. Female genital tract papillomavirus in conjunctival papillomas of infancy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:551–2. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eichler MD, Fraunfelder FT. Cryotherapy for conjunctival lymphoid tumors. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:463–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75797-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eng HL, Lin TM, Chen SY, et al. Failure to detect human papillomavirus DNA in malignant epithelial neoplasms of conjunctiva by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:429–36. doi: 10.1309/RVUP-QMU3-5X6W-3CQ1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ensoli B, Sgadari C, Barillari G, et al. Biology of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1251–69. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erie JC, Campbell RJ, Liesegang TJ. Conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial and invasive neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:176–83. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Falcó Jover G, Martínez Egea A, Sánchez Cuenca J, et al. Regression of primary gastric B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1999;91:541–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feldmann G, Nischalke HD, Nattermann J, et al. Induction of interleukin-6 by hepatitis C virus core protein in hepatitis C-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia and B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4491–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feltgen N, Auw-Hädrich C. Exceptional conjunctival tumor in a young allergic woman. Ophthalmologe. 2005;102:1204–6. doi: 10.1007/s00347-004-1149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferreri AJ, Guidoboni M, Ponzoni M, et al. Evidence for an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:586–94. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Dognini GP, et al. Bacteriaeradicating therapy for ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: questions for an open international prospective trial. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1721–2. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, et al. Regression of ocular adnexal lymphoma after Chlamydia psittacieradicating antibiotic therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5067–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, et al. Bacteriaeradicating therapy with doxycycline in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: a multicenter prospective trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1375–82. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Viale E, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and MALT-type lymphoma of the ocular adnexa: clinical and therapeutic implications. Hematol Oncol. 2006;24:33–7. doi: 10.1002/hon.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferreri AJ, Viale E, Guidoboni M, et al. Clinical implications of hepatitis C virus infection in MALT-type lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:769–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferris DG. Colposcopy in Men. In: Ferris DG, Cox JT, OConnor DM, editors. Modern Colposcopy. 2 Kendall Hunt; Textbook and Atlas: 2004. p. 489. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferry JA, Fung CY, Zukerberg L, et al. Lymphoma of the ocular adnexa: A study of 353 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:170–84. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213350.49767.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fischbach W, Goebeler-Kolve ME, Dragosics B, et al. Long term outcome of patients with gastric marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) following exclusive Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: experience from a large prospective series. Gut. 2004;53:34–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flaitz CM, Jin YT, Hicks MJ, et al. Kaposi’s sarcomaassociated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences (KSHV/HHV-8) in oral AIDS-Kaposi’s sarcoma: a PCR and clinicopathologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:259–64. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fox JG, Beck P, Dangler CA, et al. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat Med. 2000;6:536–42. doi: 10.1038/75015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]