Abstract

Elliptical and cylindrical geometries of carbon-fiber microelectrodes were modified by covalent attachment of 4-sulfobenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate following its electroreduction. Elliptical electrodes fabricated from Thornel P-55 carbon fibers show the highest amount of 4-sulfobenzene attached to the electrode. Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry was used to compare the response to dopamine and other neurochemicals at these modified carbon-fiber microelectrodes. The grafted layer causes an increased sensitivity to dopamine and other positively charged analytes that is due to increased adsorption of analyte in the grafted layer. However, this layer remains permeable to negatively charged compounds. Modified electrodes retain the increased sensitivity for dopamine during measurements in mouse brain tissue.

Keywords: Carbon-fiber microelectrode, diazonium salt, surface modification, dopamine, neurotransmitter detection

Introduction

Voltammetric microelectrodes provide a platform for the construction of sensors of the concentration fluctuations of easily oxidized neurotransmitters in the extracellular fluid of the brain1. The neurotransmitter dopamine can be detected in this way. Dopamine has shown to be of central importance to normal behavior. For example, depletion of dopamine in the striatum is a consequence of Parkinson’s disease,2 and the symptoms can be alleviated by administration of its biosynthetic precursor, L-DOPA. In addition, dopaminergic neurons are involved in brain circuitry that is important in reward and addiction.3, 4

Several sensor properties are desirable for the detection of dopamine. The sensor should have a fast response time because concentration changes in vivo occur on a sub-second time scale5. High sensitivity is required because the physiological actions of dopamine at its receptors occur at concentrations in the range from nanomolar to low micromolar.6, 7 High selectivity is required because other electroactive species are present in the extracellular fluid of the brain at much higher concentrations than dopamine. Background subtracted, fast-scan cyclic voltammetry at carbon-fiber microelectrodes has been shown to have many of these characteristics so that it is a useful technique for detection of dopamine and other oxidizable neurotransmitters at single biological cells and within intact tissue.8, 9 Recent improvement in instrumentation and computer control allowed this technique to achieve very high sensitivities.10–12 The basis for the high sensitivity of fast-scan cyclic voltammetry for dopamine depends is its accumulation by adsorption at the carbon surface in the time between collection of each cyclic voltammogram. An alternate approach to increase sensitivity and selectivity with carbon-fiber electrodes is to use surface coatings such as Nafion®, a perfluorinated cation-exchange polymer, or overoxidized polypyrrole.13, 14 These coatings promote dopamine accumulation at the electrode surface while rejecting anions. However, both coatings are noncovalently attached layers that have finite thickness. The time required for molecules to diffuse through the coating increases the response time of the electrode. An alternate approach to achieve high sensitivity is electrochemical overoxidation of the carbon surface.15 This appears to increase anionic sites on the surface because it promotes increased adsorption of amines that are protonated at physiological pH such as dopamine. However, overoxidation decreases selectivity and also increases the response time of the electrode to dopamine.

Savéant and coworkers introduced a procedure for covalent attachment to carbon surfaces by grafting aryl radicals produced by electrochemical reduction of diazonium salts. 16 Subsequently diazonium salt reduction has been demonstrated to be a versatile method to functionalize carbon-electrode surfaces 17–22. While strong bonding and dense packing of monolayers produced by diazonium reduction were initially established, later studies demonstrated that some aryl diazonium salts tend to form multilayer structures on the electrode surfaces.23–26 Recent research has shown that reduction of diazonuim salts at metal electrodes also forms surface layers at non-carbon electrodes.27–31

To create a dopamine sensitive and selective electrode we have modified carbon microelectrodes via reduction of 4-sulfobenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate (4-SBD). The sulfonate group can provide a cation exchange site similar to Nafion® but with a thinner grafted layer that is covalently attached to the electrode surface. In this study we compare the fast-scan cyclic voltammetric response at modified electrodes and untreated electrodes to several neurochemicals as well as examine the adsorption behavior of dopamine. In addition, the functionality of these electrodes was tested in mouse brain slices.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

All chemicals for flow injection analysis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and used as received. Solutions were prepared using doubly distilled water (Megapure system, Corning, New York). Solutions for flow injection analysis were prepared in a TRIS buffer solution, pH 7.4 containing 15 mM TRIS, 140 mM NaCl, 3.25 mM KCl, 1.2 CaCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 2.0 mM Na2SO4. This buffer mimics the ionic environment present in cerebral spinal fluid. Stock solutions of analyte were prepared in 0.1 M HClO4, and were diluted to the desired concentration with TRIS buffer on the day of use.

Synthesis and characterization of 4-sulfobenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate (4-SBD)

0.1 mol (17.3 g) of 4-aminobenzenesulphonic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 0.2 mol (37 g) of tetrafluoroboric acid (48 %) (Fischer Chemicals, Fair lawn, NJ). This solution was cooled in an ice-salt bath to −5°C. Water was added to 0.1 mol (6.9 g) sodium nitrite (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) until dissolution was complete and the nitrite solution was added dropwise to 4-aminobenzenesulphonic acid over 30 min while mechanically stirring. The resulting suspension was vacuum filtered and the white salt was washed with an ice cold ether-methanol mixture (4:1), purified by washing with small amounts of ice cold ethanol, and dried over calcium chloride. The compound was stored at 4°C. The purified compound was characterized by 400 MHz- NMR measurements. (DMSO) δ 7.80 (1H,d), 7.68 (1H,d), 7.29 (1H,d), 7.27 (1H,d) with no proton signal for the amine group. IR analysis showed a strong band at 2300 cm−1 that indicated the presence of the diazonium group. Melting point determination showed decomposition at 127°C – 130°C consistent with the range determined by Kolar32 for 4-SBD.

Electrode preparation

The microelectrodes were fabricated as previously described1 with both P-55 and T650 carbon fibers (Thornel, Amoco Corp., Greenville, SC). A single fiber was aspirated into a glass capillary and pulled on a micropipette puller (Narashige, Tokyo, Japan). For elliptical electrodes the fiber was sealed into the capillary with epoxy resin (Epon 828 with 14% m-phenlylenediamine by weight, Miller Stephenson Chemical Co., Danbury,CT). After curing the epoxy, the electrodes were polished at a 45° angle on a diamond embedded polishing wheel (Sutter Instruments), resulting in an elliptical surface of approximately 10−6 cm² for P-55 disks and 4 × 10−7 cm² for T-650 disks.

The capillaries of the microelectrodes were backfilled with electrolyte solution (4M potassium acetate, 150 mM potassium chloride), and wires were inserted into the capillary for electrical contact. Macroelectrodes were constructed by attaching contact wires to the back of glassy carbon plates (Tokai, between 1 cm² and 2 cm² surface area) with silver epoxy (H2O-PFC, EPO-TEK, Billerica, MA). The epoxy was cured for 5 minutes at 150°C. The glassy carbon plate was sealed with High Vacuum Torr Seal (Varian Vacuum Technologies) that was cured overnight at room temperature. The carbon surface was exposed by polishing with alumina slurries of 1μm, 0.3μm, and 0.05μm size subsequently.33 Before use all electrodes were soaked in isopropanol purified with Norit A activated carbon (ICN, Costa Mesa, CA) for at least 20 minutes.34

Chemical surface modification

4-sulfobenzene (4-SB) was attached to the carbon surface by electroreduction at a potential of −1.0 V vs Ag/AgCl for 5 minutes16, 18. Electrolysis was done in acetonitrile, dried over alumina before use, containing 1 mM 4-SBD and 0.1 M tetraflouroboric acid (48 %, Fischer Chemicals, Fair lawn, NJ). Dissolution of 4-SBD was aided by 5 minutes of sonication. Tetraflouroboric acid was used as electrolyte because it improved dissolution of the diazonium compound. It also provided better reproducibility of the surface layers than with tetrabutylammonium tertrafluoroborate as electrolyte. The small amount of water added with the tetraflouroboric acid did not adversely effect the formation of the grafted layer because the covalent attachment also occurs following diazonium reduction in aqueous solutions 17. Before electrolysis the solution was deaerated with nitrogen for 10 minutes. For experiments examining formation of the layer cyclic voltammetry was used. The potential was cycled in 4-SBD solutions at a scan rate of 0.2 V/s from 0.5 V to −1 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 30 cycles.

XPS analysis

A Perkin Elmer PHI 5400 ESCA instrument with an Mg X-ray source was used. For survey scans, three scans were averaged: 0.5 eV/step, 50 msec/step with a pass energy of 89.45 eV, and a work function of 4.75 eV. Multiplex scans to determine the percentage composition of the sample surface were done with 0.1 eV/step, 50 msec/step, pass energy 35.75 eV, and a work function of 4.75 eV. For all multiplex scans, nine scans were taken and averaged.

Electrochemical measurements

Cyclic voltammograms were acquired and analyzed using locally constructed hardware and software written in LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX) that has been described previously11, 15. The electrochemical cell was placed inside a grounded Faraday cage to minimize electrical noise. For flow–injection analysis the electrode was positioned at the outlet of a 6-port rotary valve. A loop injector was mounted on an actuator (Rheodyne model 5041 valve and 5701 actuator) that was controlled by a 12-V DC solenoid valve kit (Rheodyne, Rohnert Park, CA) and introduced the analyte to the surface of the electrode. Solution was driven with a syringe infusion pump (2 cm/s, Harvard Apparatus Model 22, Holliston, MA) through the valve and the electrochemical cell.

For fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, the rest potential was normally −0.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Triangular excursions were to 1.0 V at a scan rate of 300 V/s. The waveform was repeated at a frequency of 10 Hz.

Measurements in brain slices

Coronal brain slices, 300 μm thick, from C57 black mice were prepared using a Lancer Vibratome (Technical Products International Inc., St.Louis, MO, USA)35, 36. The slices were placed in a recording chamber and superfused for 45 min with a preheated (34°C) Krebs buffer before recordings were made. The buffer consisted of 126 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 2.4 mM CaCl2, 25 mM NaHCO3, 11 mM dextrose and 20 mM HEPES. The buffer was adjusted to pH 7.4 and saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Stimulating and working electrodes were inserted 75 μm below the surface in the dorsal lateral caudate-putamen. The placement was made with the aid of a stereomicroscope and a stereotaxic atlas37. Local electrical stimulation was accomplished with a bipolar tungsten electrode and consisted of a single bipolar (2 ms each phase), constant current pulse with an amplitude of 350 μA. Data was acquired and collected with the same equipment as for flow injection analysis except that an Axopatch 200B served as the potentiostat (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices Cooperation, Chicago, Illinois). The cyclic voltammetry parameters were the same as used for flow-injection analysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Growth of sulfobenzene layers

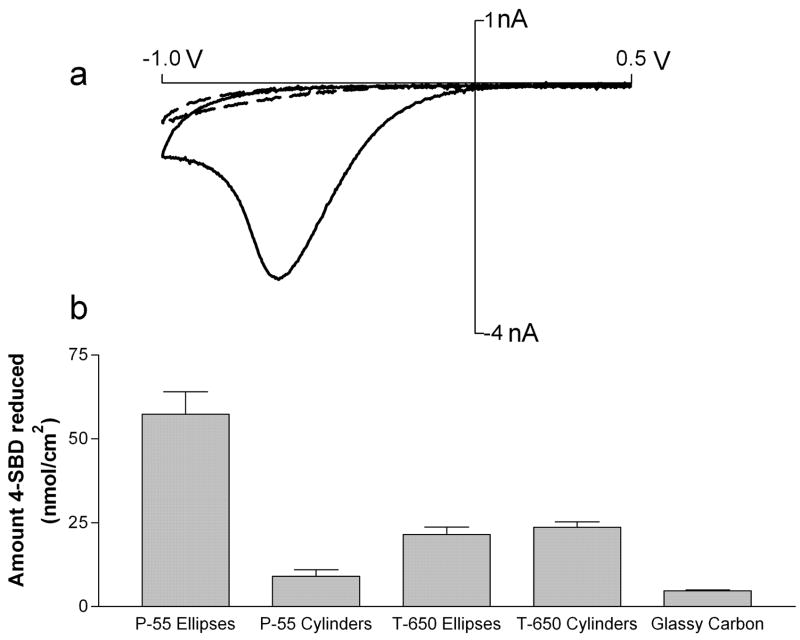

Figure 1a shows a cyclic voltammogram at 200 mV/s for the reduction of 4-SBD at P-55 elliptical electrodes. During the first cycle the reduction current approached the expected limiting current and then declined, peaking at ~ −0.65V vs Ag/AgCl. This wave was absent in subsequent cycles, a behavior observed at all types of electrodes. The peaked shape of the initial cyclic voltammogram and the diminished current on the second scan both indicate surface passivation following 4-SB attachment. The amount of the diazonium reduced was calculated by integrating the current under the voltammetric wave during the first cycle. The amounts obtained for different geometries of microelectrodes and a normal sized glassy carbon electrode are shown in figure 1b. P-55 elliptical electrodes showed the highest surface coverage of 57.5 nmol/cm2 whereas P-55 cylindrical microelectrodes fabricated from the same fiber only showed 9 nmol/cm2. Cylinders and ellipses fabricated from T-650 carbon fibers, on the other hand, showed no significant difference in amount reduced (21.5 ± 5.3 and 23.7 ± 4.0 for T-650 disks and cylinders respectively), with an amount reduced that is about 2.5 times smaller than observed at P-55 disks. T-650 carbon fibers have a polyacrylonitrile (PAN) precursor, and the structure is thought to consist of mostly disordered regions of basal and edge planes33. Thus, the surfaces at T-650 disks and T-650 cylinders are expected to have similar reactivities. In contrast, P-55 carbon fibers are produced from a pitch precursor with the basal planes ordered in concentric layers around the core. This should give a higher fraction of edge sites at the fiber end than on the cylindrical surface. Thus, the elliptical area should be more reactive than the shaft of the P-55 cylinder, consistent with the higher amounts of 4-SBD reduced.

Figure 1.

Modification of carbon electrodes with 4-SBD. (a) Cyclic voltammograms for the reduction of 1 mM 4-SBD at P-55 disk electrode in acetonitrile containing 0.1M HBF4. Solid line: first cycle; Dashed line: second cycle. (Peak potential for reduction −0.65V vs Ag/AgCl) (b) Surface coverage at different geometries after one cycle (n=6 electrodes each) Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

With dense packing a monolayer coverage would equal about 1 nmol/cm². Thus, during the first cycle a multilayer is formed at all geometries and types of electrodes examined, assuming that all the reduced 4-SBD grafts to the electrode. Multilayer formation with diazonium modification has been frequently observed. The proposed mechanism involves the intermediate radical species reacting not only with the electrode surface, but, following diffusion, reaction with molecules already attached to the electrode.23, 24 This mechanism is favored for 4-SB grafting because, after depositing the initial monolayer on the surface, a negative charge originating in the sulfo group accumulates on the electrode. This layer can attract and orient the positively charged diazonium group.

The surface coverage determined from the reduction of 4-SDB likely overestimates the surface coverage because radical recombinations compete with surface attachment. Furthermore, oligomeric structures may also be formed, which do not graft to the surface. However, the amount of 4-SBD reduced can be taken as relative measurement of the surface concentration of 4-SB assuming a similar yield of the side reactions at each type of electrode. The attachment of sulfobenzene was confirmed with XPS measurements at glassy carbon electrodes treated with the same cathodic potential. Survey scans showed a sulfur S2p peak at 169 eV which was absent in blank samples. The sulfur to carbon ratio was increased 1.8-fold in a sample electrolyzed for 5 minutes compared to a one cycle reduction suggesting further layer growth after the first cycle as described previously.38 In subsequent experiments, all electrodes were therefore electrolyzed for 5 minutes at −1.0 V vs Ag/AgCl in 4-SDB solution. Modified in this way, electrodes can be stored in air at room temperature for up to a month without alteration of their electrochemical properties.

Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry at electrodes with grafted 4-sulfobenzene

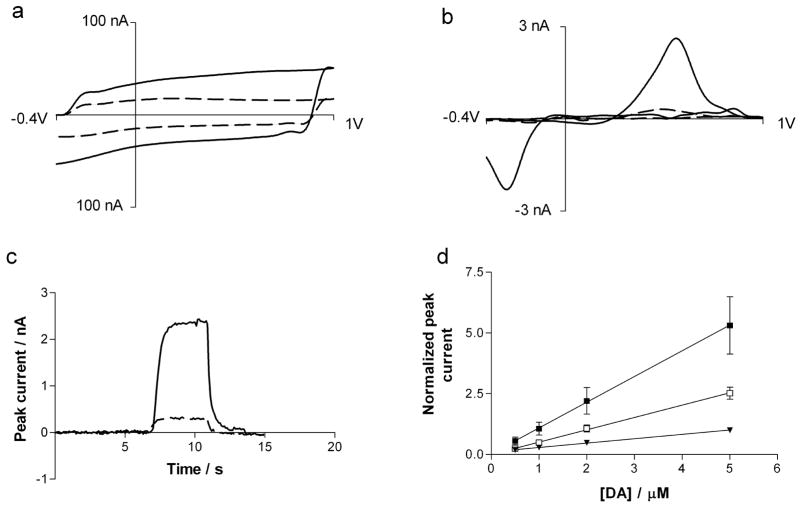

Figure 2 compares the fast-scan cyclic voltammetric results at bare electrodes and electrodes with grafted 4-SB. The background current, arising from double layer charging and oxidation of surface functional groups is larger after modification. This is attributed to an increased electrode capacitance due to the grafted layer. The current for the oxidation of 5 μM dopamine at P-55 elliptical electrodes grafted with 4-SB have a peak current which is 5.3 ± 2 greater than at an unmodified surface. The covalently attached multilayer on the electrode surface serves as cation exchange membrane thus providing an opportunity for positively charged analytes to accumulate. However, the response time of 0.6 s, measured as the time required to increase from 10 to 90% of the maximum response in the flow-injection apparatus, did not change with surface modification. This indicates that diffusional transport through the layer is not significantly retarded.

Figure 2.

Characterization of 4SBD modified electrodes in pH 7.4 Tris buffer. (a–c): The response at bare electrodes is shown in dashes lines, while the response at modified electrodes is shown in solid lines. (a): Background cyclic voltammogram at 300 V/s form −0.4 V to 1.0V at a repletion rate of 10 Hz. (b): Background-subtracted cyclic voltammogram for 5 μM dopamine (c) Peak oxidation current for dopamine measured following a bolus injection of dopamine. (d) Calibration curve for dopamine at untreated electrodes (▼) and at 4SBD modified P-55 ellipses (■) and modified T-650 cylinders (□) (n=5 electrodes each). Due to variations between electrodes the peak oxidation current for dopamine was normalized to the current obtained at bare electrodes for 5 μM dopamine injection. Error bars represent SEM.

The peak current for dopamine oxidation is linear with concentration from 500 nM to 5 μM. However, as shown in figure 2d, the increase in peak current for dopamine at T-650 cylindrical electrodes with grafted 4-SB is 2.5 ± 0.5, only half of the increase seen at P-55 ellipses. This reduced sensitivity correlates well with the lower amounts of 4-SBD reduced seen at cylindrical T-650 electrodes (figure 1). The increased sensitivity was stable even after cycling the potential at 50 Hz repetition rates for several hours.

Dopamine adsorption at electrodes grafted with 4-sulfobenzene

The high sensitivity for dopamine at untreated carbon fiber electrodes is the result of adsorption of dopamine to the electrode in between each scan. To compare adsorption at untreated and modified P-55 elliptical electrodes, adsorption isotherms for dopamine were constructed. The peak current at various concentrations of dopamine from 0.5 μM to 500 μM were measured at each type of electrode. The peak current measured has two essential contributors: adsorption and diffusion. The expected current due to diffusion control was computed with DigiSim® and subtracted from the total peak current to obtain the current due to adsorbed dopamine. By integration of this current over time it is possible to calculate the surface coverage. At unmodified electrodes, dopamine adsorption to carbon-fiber electrodes follows the equation for a Langmuir isotherm34:

| (1) |

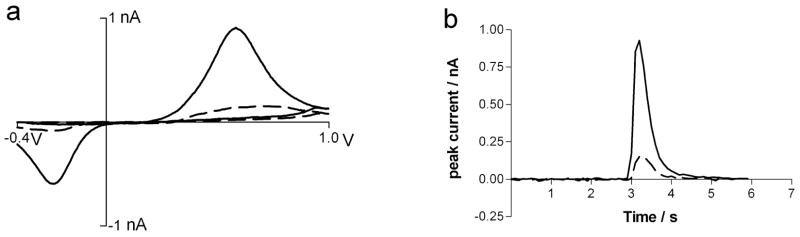

where ΓDA is the surface concentration of dopamine, Γs is the saturation coverage, and β is the equilibrium constant for adsorption. Consistent with prior work, the isotherm for bare P-55 elliptical electrodes fits well to equation 1 with a limiting coverage of Γs = 10−10 mol/cm2 and β = 2.8 × 10−5 cm3/pmol 15, 34, 38. The adsorption isotherm for 4-SBD modified electrodes shown in figure 3a does not follow equation (1). A more complex model is needed to describe the adsorption. With the arbitrary addition of a linear component with a slope of 3.5 × 10−3 cm to equation 1 an isotherm with τs of 10−9 mol/cm2 and an equilibrium constant of 2.3 × 10−5 cm3/pmol does fit to the data. Thus the data indicates a 10-fold increase in saturation coverage at the modified electrode lead to the higher sensitivity.

Figure 3.

Adsorption characteristics of dopamine at P-55 elliptical electrodes. (a) Fit of the experimentally obtained surface coverage (■) to an adsorption isotherm (solid line). The isotherm is a summation of a regular Langmuir-isotherm (dotted line) and a linear component (dashed line). (b) The effect of rest potential on the peak current for dopamine. Values are normalized to the current obtained with a holding potential of −0.4V. Open bars show the response for bare P-55 disk electrodes and filled bars for 4SBD modified P-55 ellipses (n=5 electrodes). Error bars represent SEM

Dopamine adsorption at untreated electrodes increases with more negative rest potentials at which the electrode is held between scans.15 This effect is attributed to the greater negative charge on the surface at more negative potentials. At 4-SBD electrodes this effect is removed (Figure 3b). This further indicates that the increased dopamine adsorption at 4-SB electrodes is due to the added sulfo group that predominates over the effect of the applied potential.

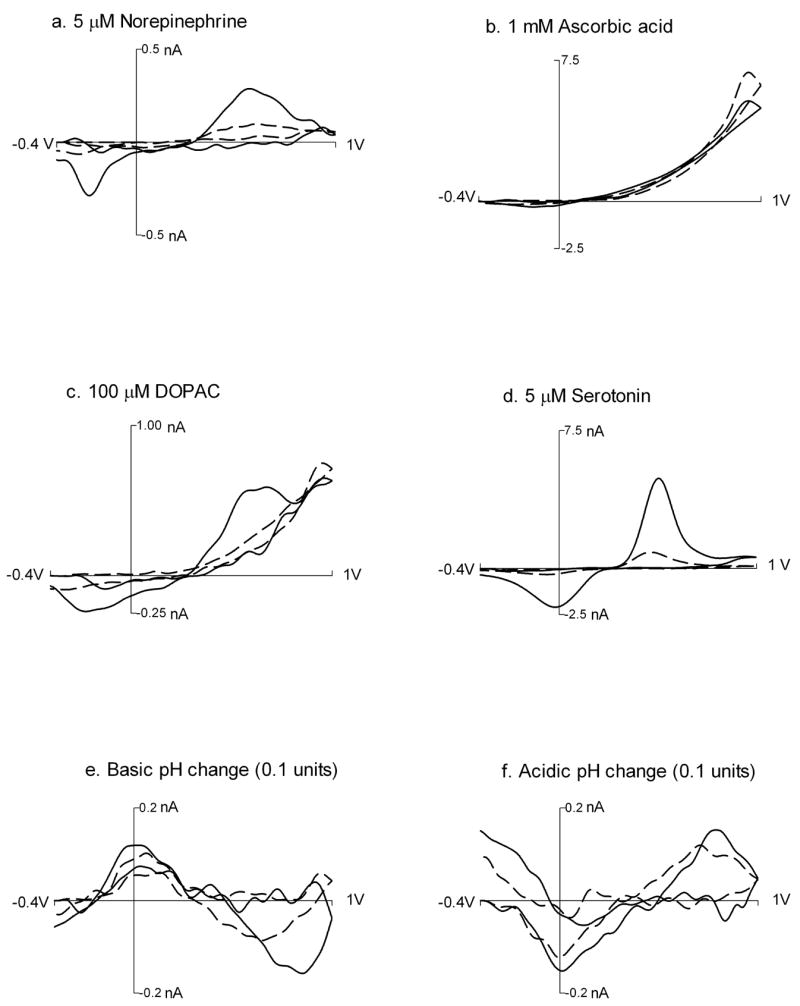

Voltammetric response to other compounds

The selectivity for dopamine detection with modified electrodes was examined by comparing its background-subtracted cyclic voltammogram to those for a variety of other neurochemical species. The analytes studied included the metabolites of dopamine (dihydroxy phenyl acid (DOPAC), homovanilic acid (HVA) and 3-methoxytyramine (3-MT)), other neurotransmitters like norepinephrine (NE) and serotonin (5-HT) and its metabolite 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA), as well as other easily oxidized substances such as uric acid (UA) and ascorbic acid (AA). The response to pH was also examined. Untreated carbon-fiber electrodes respond to pH changes because one of the contributors to the background is electrolysis of oxide groups on the carbon surface.39 A pH change therefore causes a background shift that is enhanced by the background subtraction process. In vivo, pH changes have been measured following electrical stimulation of dopamine neurons and have been shown to be an indirect measure of dilation of blood vessels.40

Representative cyclic voltammograms at polished disks and modified electrodes for several of the substances tested are shown in figure 4. At pH 7.4 the protonated amines, dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and 3-MT, all show increased amplitudes at modified electrodes indicating accumulation in the grafted layer. The amplitudes of the cyclic voltammograms for the compounds that are anions at physiological pH are not significantly different from the responses at polished elliptical electrodes indicating that they are unaffected by the layer. This observation, coupled with the unaltered response time of the modified electrodes, indicates that the grafted layer is quite permeable. Given the branch-like structure that evolves from multilayer formation, this result is not surprising but in contrast to blocking effects that have been observed at electrodes after reduction of other aryl-diazonium compounds that lead to monolayer formation41. It is likely that 4-SBD under the conditions presented in this study forms a different structured layer than the 4-nitro analogue. The modification seems to increase the sensitivity for pH changes by a factor of about 2.

Figure 4.

Background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms for various compounds. Response at bare P-55 elliptical electrodes is shown with dashed lines while the response at 4-SBD modified electrode is shown with solid lines. The cyclic voltammograms were recorded in a flow injection cell 300 ms following injection of the analyte.

The shapes of the cyclic voltammograms are used to identify substances detected in vivo. To evaluate quantitatively the similarities in the shapes of the voltammograms, a correlation coefficient (Table 1) was computed for each cyclic voltammogram with that for dopamine.42, 43 The correlation coefficients are computed by recording a template cyclic voltammogram for dopamine at each electrode and comparing the set of other analytes to it. To do this the oxidation peak is normalized to the amplitude of the oxidation peak in the dopamine template. Then the mean square error is calculated for each cyclic voltammogram versus the template. The more similar the cyclic voltammogram is to that of dopamine, the closer to unity the correlation coefficient will be. Before modification, the cyclic voltammograms for all of the analytes except NE show a correlation coefficient of less than 0.85 when compared to dopamine, and the correlation coefficient decreases for the majority of compounds after modification. The structure of norepinephrine is very similar to that of dopamine, differing only by a hydroxyl group on the side chain. Thus, 4-SB modified electrodes not only show higher sensitivity but also have higher selectivity for dopamine then polished carbon fiber electrodes.

Table 1.

Sensitivity and selectivity of 4-SBD modified electrodes

| DOPAC | 3-MT | HVA | 5-HT | 5-HIAA | NE | AA | UA | Acidic pH | Basic pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in signal | 0.78 ± 0.36 | 5.83 ± 2.53 | 0.91 ± 0.63 | 4.27 ± 1.70 | 1.28 ± 0.43 | 2.14 ± 1.00 | 1.08 ± 0.34 | 0.83 ± 0.28 | 2.73 ± 1.24 | 2.45 ± 1.28 |

| R bare electrode | 0.57 ± 0.10 | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 0.47 ± 0.09 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.68 ± 0.07 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.10 | 0.45 ± 0.08 | 0.59 ± 0.11 | −0.61 ± 0.11 |

| R modified electrode | 0.51 ± 0.06 | 0.79 ± 0.09 | 0.40 ± 0.08 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.10 | 0.32 ± 0.13 | 0.37 ± 0.10 | −0.49 ± 0.11 |

First row: Maximal amplitude of the peak current at modified electrodes relative to that at unmodified electrodes for various analytes. Second/Third row: Correlation coefficient r between the cyclic voltammogram for dopamine and for the various other neurochemical for bare P-55 elliptical electrodes and for 4SBD modified P-55 disk electrodes (n= 7 electrodes). Values are given with standard deviations

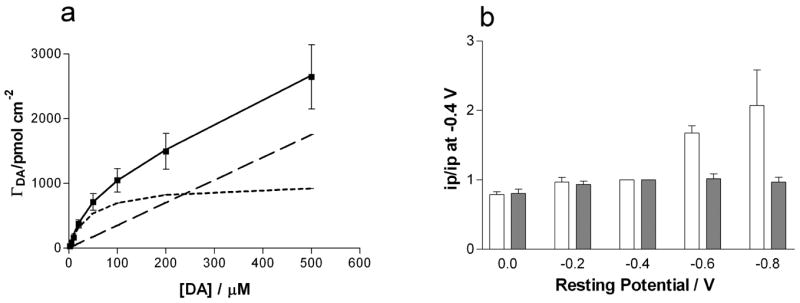

Use in brain slices

To evaluate the performance of 4-SB modified electrodes in a neurochemical application, they were used in a mouse brain slices containing the caudate-putamen, a region with multiple dopamine terminals. Dopamine release was evoked by local depolarization of the nerve terminals with a bipolar stimulating electrode. The carbon-fiber microelectrode was placed adjacent to the stimulating electrode to monitor the release. Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry responses at bare and modified P-55 ellipses were compared (n =4 for each electrode type, example responses in Figure 5). In all cases, the 4-SB modified electrode showed larger signals. Based on the signal-to-noise ratios in brain slices, a detection limit of 30 nM dopamine was calculated. This is a factor of 5 more sensitive than the detection limit at bare elliptical electrodes. As shown in figure 5b the time response is the same at 4-SB modified electrode compared to bare electrodes. The modified electrode maintained its sensitivity for dopamine over the time course of the experiment.

Figure 5.

Dopamine detection in mouse brain slices with carbon fiber electrodes. Response at bare P-55 elliptical electrodes is shown with dashed lines while the response at 4-SBD modified electrode is shown with solid lines. a) Background subtracted cyclic voltammograms measured following a single pulse, 350 μA stimulation. b) Temporal response to the same stimulations shown in figure 5a) obtained for the oxidation current of dopamine.

Summary

The results show that electrochemical reduction of 4-SBD forms a covalently attached cation-exchange multilayer on carbon-electrode surfaces. 4-SB modified electrodes are an alternative to Nafion-coated13 and to overoxidized15 electrodes to achieve improved detection of dopamine. With this layer attached, adsorption of dopamine to carbon fibers is increased in a manner that is potential independent. The highest reactivity to 4-SBD was found for P-55 elliptical electrodes, and they showed the greatest increase in dopamine signal. Increased adsorption led to an increase in sensitivity for dopamine by a factor of 5 with a concomitant increase in selectivity. This increase is in the same range of what can be achieved with overoxidation and much higher than the current increase seen at Nafion-coatings which is reported to be 1.513. However, in contrast to Nafion, the 4-SB layer does not exclude negatively charged compounds. Furthermore the time response of the electrode is unaffected by 4-SBD modification which makes it advantageous over the other two method which both slow down response time. This indicates that the grafted layer has a very open structure as expected for a multilayer graft following diazonium salt reduction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supplied by NIH.

References

- 1.Kawagoe KT, Zimmerman JB, Wightman RM. Journal of neuroscience methods. 1993;48:225–240. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(93)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper JS, Bloom FE, Roth RH. The biochemical basis of Neuropharmacology. 7 Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz W, Apicella P, Ljungberg T. J Neurosci. 1993;13:900–913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-00900.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waelti P, Dickinson A, Schultz W. Nature. 2001;412:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35083500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pothos EN, Davila V, Sulzer D. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4106–4118. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04106.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berke JD, Hyman SE. Neuron. 2000;25:515–532. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richfield EK, Penney JB, Young AB. Neuroscience. 1989;30:767–777. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garris PA, Wightman RM. Neuromethods: Voltammetric Methods in Brain Systems. Humana Press; Totowa, N.J: 1995. Chapter 6 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis ER, Wightman RM. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 1998;27:77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michael D, Travis ER, Wightman RM. Analytical Chemistry. 1998;70:586a–592a. doi: 10.1021/ac9819640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michael DJ, Joseph JD, Kilpatrick MR, Travis ER, Wightman RM. Analytical Chemistry. 1999;71:3941–3947. doi: 10.1021/ac990491+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahill PS, Walker QD, Finnegan JM, Mickelson GE, Travis ER, Wightman RM. Analytical Chemistry. 1996;68:3180–3186. doi: 10.1021/ac960347d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baur JE, Kristensen EW, May LJ, Wiedemann DJ, Wightman RM. Analytical Chemistry. 1988;60:1268–1272. doi: 10.1021/ac00164a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pihel K, Walker QD, Wightman RM. Analytical chemistry. 1996;68:2084–2089. doi: 10.1021/ac960153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heien ML, Phillips PE, Stuber GD, Seipel AT, Wightman RM. Analyst. 2003;128:1413–1419. doi: 10.1039/b307024g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delamar M, Hitmi R, Pinson J, Saveant JM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114:5883–5884. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delamar M, Desarmot G, Fagebaume O, Hitmi R, Pinson J, Saveant JM. Carbon. 1997;35:801–807. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allongue P, Delamar M, Desbat B, Fagebaume O, Hitmi R, Pinson J, Saveant JM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1997;119:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Downard AJ, Roddick AD. Electroanalysis. 1995;7:376–378. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downard AJ, Roddick AD, Bond AM. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1995;317:303–310. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu YC, McCreery RL. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1995;117:11254–11259. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinson J, Podvorica F. Chemical Society Reviews. 2005;34:429–439. doi: 10.1039/b406228k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kariuki JK, McDermott MT. Langmuir. 1999;15:6534–6540. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kariuki JK, McDermott MT. Langmuir. 2001;17:5947–5951. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anariba F, DuVall SH, McCreery RL. Analytical Chemistry. 2003;75:3837–3844. doi: 10.1021/ac034026v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Amours M, Belanger D. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2003;107:4811–4817. doi: 10.1021/jp027223r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dequaire M, Degrand C, Limoges B. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1999;121:6946–6947. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adenier A, Bernard MC, Chehimi MM, Cabet-Deliry E, Desbat B, Fagebaume O, Pinson J, Podvorica F. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123:4541–4549. doi: 10.1021/ja003276f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chausse A, Chehimi MM, Karsi N, Pinson J, Podvorica F, Vautrin-Ul C. Chemistry of Materials. 2002;14:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boukerma K, Chehimi MM, Pinson J, Blomfield C. Langmuir. 2003;19:6333–6335. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laforgue A, Addou T, Belanger D. Langmuir. 2005;21:6855–6865. doi: 10.1021/la047369c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolar GF. Zeitschrift fuer Naturforschung, Teil B: Anorganische Chemie, Organische Chemie, Biochemie, Biophysik, Biologie. 1972;27:1183–1185. doi: 10.1515/znb-1972-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCreery RL. Laboratory Techniques in Electroanalytical Chemistry. Dekker; New York: 1996. Chapter 10 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bath BD, Michael DJ, Trafton BJ, Joseph JD, Runnels PL, Wightman RM. Anal Chem. 2000;72:5994–6002. doi: 10.1021/ac000849y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alger BE, Dhanjal SS, Dingledine R, Garthwaite J, Henderson G, King GL, Lipton P, North A, Schwartzkroin PA, Sears TA, Seagal M, Whittington TS, Williams J. Brain Slices. Plenum Press; New York: 1984. pp. 381–438. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy RT, Jones SR, Wightman RM. J Neurochem. 1992;59:449–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paxinos W, Watson C. Academic Press; Orlando, Florida: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solak AO, Ranganathan S, Itoh T, McCreery RL. Electrochemical and Solid-State Letters. 2002;5:E43–E46. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Runnels PL, Joseph JD, Logman MJ, Wightman RM. Analytical Chemistry. 1999;71:2782–2789. doi: 10.1021/ac981279t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venton BJ, Zhang H, Garris PA, Phillips PE, Sulzer D, Wightman RM. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1284–1295. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saby C, Ortiz B, Champagne GY, Belanger D. Langmuir. 1997;13:6805–6813. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Troyer KP, Heien ML, Venton BJ, Wightman RM. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2002;6:696–703. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venton BJ, Wightman RM. Analytical Chemistry. 2003;75:414A–421A. [Google Scholar]