Abstract

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) nucleocapsid or core antigen (HBcAg) is extremely immunogenic during infection and after immunization. For example, during many chronic infections, HBcAg is the only antigen capable of eliciting an immune response, and nanogram amounts of HBcAg elicit antibody production in mice. Recent structural analysis has revealed a number of characteristics that may help explain this potent immunogenicity. Our analysis of how the HBcAg is presented to the immune system revealed that the HBcAg binds to specific membrane Ig (mIg) antigen receptors on a high frequency of resting, murine B cells sufficiently to induce B7.1 and B7.2 costimulatory molecules. This enables HBcAg-specific B cells from unprimed mice to take up, process, and present HBcAg to naive Th cells in vivo and to T cell hybridomas in vitro approximately 105 times more efficiently than classical macrophage or dendritic antigen-presenting cells (APC). These results reveal a structure–function relation for the HBcAg, confirm that B cells can function as primary APC, explain the enhanced immunogenicity of HBcAg, and may have relevance for the induction and/or maintenance of chronic HBV infection.

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) nucleocapsid or core antigen (HBcAg) possesses unique immunologic features. For example, HBcAg can function as both a T cell-independent and T cell-dependent antigen (1); as little as 0.025 μg of HBcAg injected in saline can elicit antibody production without the need of an adjuvant (2); immunization with HBcAg preferentially primes Th1 cells (2); HBcAg is an effective carrier for heterologous epitopes (3); and HBcAg-specific Th cells mediate anti-envelope as well as anti-HBc antibody production (4). These immunologic characteristics are unique to the particulate HBcAg and do not pertain to a nonparticulate secreted form of this protein, namely the HBeAg. Recent cryoelectron microscopy studies have elucidated the structure of HBcAg to a resolution of 7.4 Å to 9 Å (5, 6). The dimer clustering of subunits produces spikes on the surface of the core shell, which consist of radial bundles of four long α-helices (5, 6). The orientation of the array of protein spikes distributed over the surface of the HBcAg shell particle may be optimal for cross-linking B cell membrane Ig (mIg) antigen receptors especially because the dominant B cell epitope appears to be positioned on the tip of the spikes (5). Because antigen structure most likely affects B cell recognition and antigen uptake and processing (7), we examined antigen presentation of the HBcAg by B cell and by non-B cell antigen-presenting cells (APC). For this purpose, we used T cell hybridomas, which recognize their respective HBcAg-specific T cell site regardless of the structural form of the antigen (i.e., HBcAg, particulate; HBeAg, aggregates; P16, monomeric subunit polypeptide; or minimum peptidic site), cultured with various APC populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/10 (B10), B10.S, (B10 × B10.S)F1, C3H/HeJ, and C57BL/6 (B6) mice were obtained from the breeding colony of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI, La Jolla, CA). The B cell knockout (μMT) mice originally produced by K. Rajewsky (8) were backcrossed onto B6 mice and were kindly provided by W. Weigle (TSRI).

Recombinant Proteins and Synthetic Peptides.

The HBV core gene encodes two polypeptides. Initiation of translation at the first start codon (AUG) results in a 25-kDa precore protein that is secreted as HBeAg after removal of 19 residues of the leader sequence and 34 C-terminal amino acids. Initiation of translation at the second AUG leads to the synthesis of a 183-aa, 21-kDa protein that assembles to form 27-nm particles that comprise the virion nucleocapsid (HBcAg). Although HBeAg and HBcAg are serologically distinct, these Ag are cross-reactive at the level of Th cell recognition because they are colinear throughout most of their primary sequence. Recombinant HBcAg of the ayw subtype was produced in Escherichia coli and purified as described (3). A recombinant HBeAg corresponding in sequence to serum-derived HBeAg encompassing the 10 precore amino acids, remaining after cleavage of the precursor, and residues 1–149 of HBcAg was produced as described (9). An aliquot of truncated HBcAg was reduced and denatured by boiling in SDS-2-mercaptoethanol (1.0%) and alkylated. This preparation consisted predominantly of monomers (16 kDa) with some dimer formation upon nonreducing PAGE and was designated P16. P16 does not bind HBcAg or HBeAg-specific mAb.

Peptides were synthesized by the simultaneous multiple-peptide synthesis method (kindly provided by Richard Houghton, Torrey Pines Institute for Molecular Studies, La Jolla, CA). The following HBcAg-derived synthetic peptides representing Th cell recognition sites were used and designated by amino acid position from the N terminus of HBcAg: 120–131 (IAs), VSFGVWIRTPPA; 129–140 (IAb), PPAYRPPNAPIL; and 120–140, a 21-mer comprising both T cell sites.

Serology.

Anti-HBc and anti-HBe IgG were measured in murine sera by an indirect solid-phase ELISA by using HBcAg or HBeAg as the solid-phase ligand as described previously (3). The data are expressed as antibody titer representing the reciprocal of the highest dilution of sera required to yield an OD492 reading three times that of preimmunization sera.

Determination of Ag-Specific Cytokine Production.

Groups of five B6 or μMT mice each were immunized with 10 μg of HBcAg or 50 μg of peptide 129–140 emulsified in Freund’s incomplete adjuvant in the hind footpads, and 10 days later lymph node (LN) cells were harvested, pooled, and cultured (8 × 106/ml) with various concentrations of HBcAg. Culture supernatants (SN) were harvested at 24 h for IL-2 determination. IL-2 was measured by the ability of SN to stimulate proliferation of the IL-2- and IL-4-sensitive NK-A cell line in the presence of mAb 11B11 specific for IL-4. IL-2 production is expressed as cellular proliferation of the NK-A cell line corrected for background.

Production of HBcAg-Specific T Cell Hybridomas.

HBcAg-specific T cell hybridomas were generated by using a standard protocol. Briefly, draining LN cells from B10 or B10.S mice were harvested 15 days after injection in the hind footpads with 4 μg of HBcAg emulsified in CFA. LN cells were pooled, and single-cell suspensions were stimulated in vitro with HBcAg (0.1 μg/ml) for 3 days. Thereafter the cells were washed and recultured with interleukin 2 (IL-2) (20 units/ml) for an additional 2 days. The cells were than washed and hybridized with the HAT-sensitive fusion partner BW 5147, which does not contain functional mRNA for the α or β chains of the T cell receptor (TCR) (10). HBcAg-specific hybridomas were cloned by limiting dilution.

Fractionation of Splenic APC Populations.

For non-B cell APC, spleen cells from unprimed B10 or B10.S mice were depleted of T cells and B cells by treatment with anti-Thy1 and J11d mAbs, respectively, plus complement and irradiated (2500 R) to inactivate any residual B cell APC function (11). This population is designated as MØ/DC. For B cell APC, T cell-depleted spleen cells from unprimed B10 or B10.S mice were enriched for B cells by removal of plastic adherent cells and passage of the nonadherent cells over a G-10 Sepharose column or by Percoll density gradient fractionation.

RNA Preparation and Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated by using Trizol (GIBCO/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and was reverse-transcribed to cDNA according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. For the detection of B7.1, B7.2, or β-actin, 2 or 5 μl of cDNA was used for the PCR amplification. The primer sequences used for detection of B7.1 were as published (12), the β-actin-specific primers were purchased from Stratagene, and the B7.2-specific primers were: (F) GCCACCCACAGGATCAATTATCC; and (R) CTGAAGCTGTAATCTCCTTCCAA, obtained from the published cDNA sequence (13). The expected sizes of the amplified products were 496 bp for B7.1, 404 bp for B7.2, and 245 bp for β-actin. A 100-bp ladder was used as a DNA size marker. To avoid saturation of the PCR, the number of thermal cycles used was determined empirically (data not shown).

RESULTS

The Uptake of HBcAg by Splenic APC Is Very Rapid.

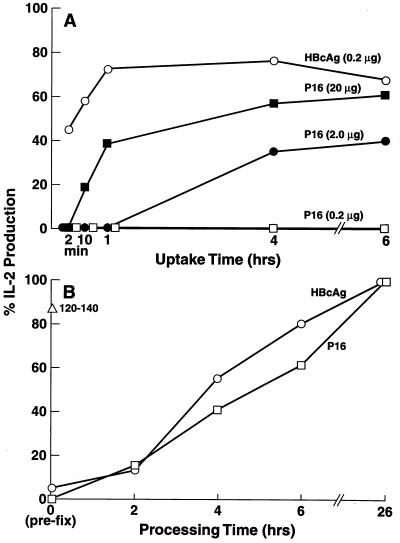

By using unprimed (naive) spleen cells as the source of APC for the activation of HBcAg-specific T cell hybridomas, it was noted that the uptake of HBcAg was very rapid (45.2% at 2 min), whereas comparable uptake of the polypeptide subunit, P16, required several hours even at a 100-fold-higher concentration (20 μg/ml) used for the pulsing of the APC (Fig. 1A). The time required for the uptake of the P16 monomer depended on antigen concentration. Antigen processing times for the HBcAg particle and the polypeptide subunit were approximately equal; both antigens required 4–5 hr of processing time to achieve 50% activation of an HBcAg-specific T cell hybridoma (Fig. 1B). Note that only the peptidic T cell site, 120–140, did not require antigen processing and was presented by glutaraldehyde prefixed APC.

Figure 1.

Enhanced uptake of HBcAg particles vs. the P16 monomer by splenic APC. (A) Antigen uptake. The HBcAg and P16 antigens at the indicated concentrations were “pulsed” on unprimed B10.S (H-2s) mouse spleen cells as the source of APC for various lengths of time (2 min to 6 h) or 16 h for the control culture. After the antigen-pulse phase, splenic APC (3 × 105) were vigorously washed (3×) and cultured with the IAs-restricted, HBcAg-specific T cell hybridoma 3E3–5G4 (1.2 × 104) for 24 h, and culture supernatants (SN) were harvested. IL-2 production is expressed as a percentage of IL-2 induced by APC pulsed with HBcAg or P16 for 16 h. (B) Antigen processing. Splenic APC were loaded with HBcAg (0.1 μg/ml) peptide 120–140 (0.2 μg/ml) or P16 (50 μg/ml) (a greater concentration of P16 was necessary to compensate for the enhanced uptake of HBcAg) for 15 min, and washed. The splenic APC were either prefixed with glutaraldehyde (0.025% × 30 s) before antigen loading or at 2, 4, 6, or 26 h after antigen loading. Fixation inactivates the cellular metabolism required for antigen processing. The splenic APC fixed at various time points were then cultured with the 3E3–5G4 T hybridoma, and IL-2 production relative to the 26-h processing time was determined. These experiments were performed at least three times, and the results are representative with minor differences attributable to the use of different T cell hybridomas.

B Cells Preferentially Present HBcAg to T Cell Hybridomas.

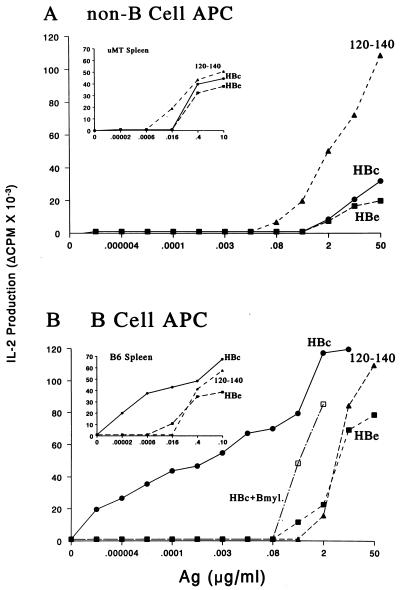

The preceding experiments suggested that the rapid uptake of HBcAg by APC may be receptor-mediated as opposed to the pinocytotic uptake of the polypeptide antigen. Receptor-mediated enhanced antigen uptake by classical adherent APC populations such as macrophages (MØ) and dendritic cells (DC) can occur through Fc receptors (FcR), which bind immune-complexed antigens (14, 15). Alternatively, B cells express mIg, which acts as a specific receptor for antigen uptake (11, 16–18). However, B cells specific for any given antigen are very rare and would not be expected to function as the predominant APC especially in the unprimed spleen cell populations used in the preceding experiments. Nevertheless, B cells were purified from unprimed spleen cells and compared with B cell-depleted cells that contained MØ and DC for their ability to function as APC for the activation (i.e., IL-2 production) of HBcAg-specific T cell hybridomas. As shown in Fig. 2A, non-B cell APC did not significantly distinguish between particulate HBcAg, nonparticulate HBeAg, or peptide 120–140 as demonstrated by the similar dose-response curves. Similar antigen dose-response curves for the three forms of the antigen were also observed when spleen cells derived from B cell-negative “knockout” mice (μMT) were used as APC for HBcAg-specific T cell hybridomas (Fig. 2A Inset). In contrast, unprimed B cells presented HBcAg approximately 105 times more efficiently than MØ/DC cells and presented HBcAg preferentially as compared with the other structural forms (i.e., HBeAg and peptide), which were presented similarly by B cells and MØ/DC cells (Fig. 2B). Comparison of the APC function of spleen cells derived from B cell-negative μMT mice and wild-type (+/+) mice (Fig. 2 Insets) confirmed that B cells were the predominant APC for the particulate HBcAg but not for the other structural forms. Consistent with the radiation sensitivity of B cell APC function (11), low-dose irradiation (2000 R) abolished the ability of B cells to present HBcAg to T cell hybridomas and had no effect on MØ/DC cell presentation of HBcAg (data not shown). Note also that a B cell myeloma, which was not specific for the HBcAg, was not able to present HBcAg to HBcAg-specific T cell hybridomas any more efficiently than MØ/DC APC. This suggested that only B cells specific for HBcAg were responsible for the extremely efficient presentation of HBcAg.

Figure 2.

B cells preferentially present the HBcAg to T cell hybridomas. (A) Spleen cells from unprimed B10(H-2b) mice were depleted of T cells and B cells and irradiated (2500 R) to inactivate any residual B cell APC function (11). Non-B cell APC (2 × 105) were cultured with the IAb-restricted, HBcAg-specific T cell hybridoma 4E4–2B9 (1.2 × 104) and media or the indicated concentrations of HBc, HBe, or the peptidic T cell site, amino acids 120–140. After 16 h, APC–T hybridoma culture SN was harvested and IL-2 was measured. (B) T cell-depleted spleen cells from unprimed B10 mice were enriched for B cells by removal of plastic adherent cells and passage of the nonadherent cells over a G-10 Sepherose column. A B cell myeloma cell line (HB99) was also used as a source of APC for HBcAg. B cell-enriched APC (2 × 105) were cultured with the 4E4–2B9 T cell hybridoma and antigens as described above. The Insets depict identical experiments except that the source of APC was either spleen cells from B cell knockout μMT mice (A) or spleen cells from wild-type (+/+) B6 mice (B). The experiments using purified APC populations were performed with a number of different IAs and IAb-restricted HBcAg-specific T hybridoma cells on at least six occasions, and the results are representative.

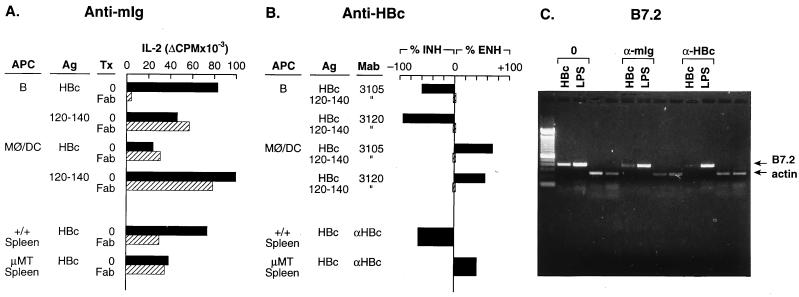

Only HBcAg-Specific B Cells Function as APC for T Cell Hybridomas.

To determine whether mIg on B cells was acting as an antigen receptor for the presentation of HBcAg to T cell hybridomas, Fab fragments (i.e., monovalent) of goat anti-mouse Ig were used as inhibitors of B cell and MØ/DC cell presentation of HBcAg or p120–140 to HBcAg-specific T cell hybridomas. Additionally, to confirm the HBcAg-specificity of the mIg receptors on B cell APC, anti-HBc mAbs 3105 and 3120 were also used as inhibitors of APC–T hybridoma activation. The presence of anti-mIg Fab fragments significantly inhibited B cell presentation of HBcAg (96.1%), but had no effect on MØ/DC presentation of HBcAg to a T cell hybridoma (Fig. 3A). Anti-mIg had no effect on p120–140 presentation by B cells or non-B cell APC. The inhibitory effect (59.3%) of anti-mIg was also observed by using unfractionated +/+ spleen cells as APC for HBcAg. The residual APC function can be attributed to the adherent cells present within the spleen. In contrast, the APC function of spleen cells from μMT mice was not affected by the presence of anti-mIg and was approximately equal to anti-mIg-treated +/+ spleen cells (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the presence of HBcAg-specific mAbs during the antigen pulse significantly inhibited B cell presentation of HBcAg (3105, 60%; 3120, 94.2%) to HBcAg-specific T hybridomas and had no effect on the presentation of peptide 120–140 by B cells or MØ/DC (Fig. 3B). Combining the two mAbs inhibited B cell presentation by 100% (data not shown). The ability of HBcAg-specific mAbs to inhibit B cell APC function confirms the importance of HBcAg-specific B cells, demonstrates that the HBcAg is not a B cell superantigen, and also indicates that soluble HBcAg-specific antibodies can compete with membrane Ig receptors for epitope binding and retard HBcAg uptake by B cells. In contrast, these same HBcAg-specific mAbs actually enhanced the presentation of HBcAg by MØ/DC APC (Fig. 3B). The enhancement likely is a result of the more rapid uptake of immune complexes by non-B cell APC mediated through the FcR (15). The FcR on B cells is not functional in antigen presentation (19). The dramatically different effects that anti-HBc antibodies exerted on the presentation of HBcAg by B cell vs. MØ/DC APC was further illustrated by the use of spleen cells derived from +/+ or μMT mice as a source of APC. Anti-HBc antibodies inhibited (65.6%) the presentation of HBcAg by splenic APC derived from +/+ mice and enhanced (41.9%) the presentation of HBcAg by splenic APC derived from μMT mice (Fig. 3B). Although both enhancing and inhibiting effects of anti-HBc antibodies occur in the +/+ splenic mixed APC population, the net inhibitory effect indicates the predominant role played by HBcAg-specific B cells in the uptake and presentation of HBcAg to the T cell hybridomas.

Figure 3.

B cell presentation of HBcAg and B cell B7.2 mRNA induction by HBcAg are mediated through HBcAg-specific mIg receptors. B cell APC were prepared from unprimed B10 (H-2b) mouse spleen, as were non-B cell APC (i.e., MØ/DC) by the methods described. (A) Inhibition of APC–T hybridoma activation by anti-mIg. Unprimed, B cell APC (2 × 105) were cultured with HBcAg (1.0 μg/ml) or peptide 120–140 (2.5 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of goat anti-mIg Fab fragments (25 μg/ml) or goat Ig (25 μg/ml) for 1 h before the addition of 1.2 × 104 IAb-restricted, HBcAg-specific T hybridoma (7B7–1A12) cells. MØ/DC APC (2 × 105) were cultured with a 10-fold-higher concentration of HBcAg (10 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of Fab anti-mIg 1 h before the addition of the 7B7–1A12 T hybridoma cells. The APC–T hybridoma cells were cultured for 16 h, and SN was collected for determination of IL-2 production. Assays were also performed by using either unprimed +/+ B6 spleen cells (1.0 μg of HBcAg) or μMT spleen cells (10 μg/ml of HBcAg) as the source of APC. (B) Inhibition of APC–T hybridoma activation by anti-HBc antibodies. Unprimed, B cell APC (2 × 105) were “pulsed” with HBcAg (1.0 μg/ml) or 120–140 (2.5 μg/ml) for 30 min in the presence or absence of anti-HBc mAb 3105 (5 μg/ml) or mAb 3120 (5 μg/ml), washed, and then cultured with HBcAg-specific T hybridoma 7B7–1A12 cells (1.2 × 104) for 16 h, and SN were harvested for IL-2 measurement. MØ/DC APC were cultured similarly, but were “pulsed” with 10 μg/ml of HBcAg and 2.5 μg/ml of 120–140 for 1 h in the presence or absence of anti-HBc mAbs. Similarly, unprimed spleen cells from either +/+ B6 mice or μMT mice were used as the source of APC in some experiments, and rabbit anti-HBc polyclonal antibodies were used with spleen cell APC. The data are expressed as a percentage of change in T hybridoma IL-2 production because of the presence of anti-HBc antibody as compared with IL-2 production in the absence of antibody. Anti-HBc antibodies inhibited (INH) or enhanced (ENH) HBcAg-specific T hybridoma activation depending on the source of the APC. (C) Inhibition of HBcAg-specific induction of B7.2 mRNA in B cells by anti-mIg and anti-HBc antibodies. Unprimed, splenic B cells derived from B10.S mice were cultured with HBcAg (2.0 μg/ml) or the B cell mitogen LPS (10 μg/ml) without added antibody (0) or in the presence of goat anti-mIg Fab fragments (25 μg/ml) or rabbit anti-HBc polyclonal antibody (1:150) (Dako). After 48 h of culture the B cells were harvested, and the presence of B7.2 and β-actin mRNA was determined by RT-PCR. The RT-PCR was performed as described in Fig. 5. All the experiments depicted in Fig. 3 were performed at least three times, and the results are representative.

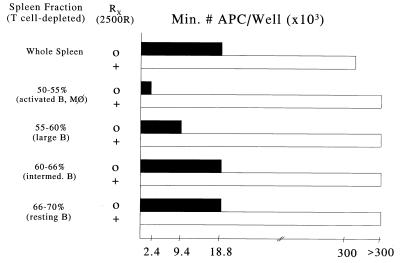

The Precursor Frequency of HBcAg-Specific B Cells in Naive Spleen Is High.

Because the B cell populations used in the preceding experiments were derived from unprimed mice never exposed to the HBcAg, the results suggested a rather high precursor frequency for HBcAg-specific B cells in naive mouse spleen. Therefore, limiting dilution analysis of B cell APC function was performed. Unprimed, T cell-depleted spleen cells were fractionated on Percoll gradients, and the density-purified B cell populations were assayed as APC for HBcAg-specific T cell hybridomas. As few as 2.4 × 103 low-buoyant-density (50–55%) large, activated B cells per well resulted in HBcAg-specific T hybridoma activation. Even the high-density (66–70%) resting B cell population was capable of presenting HBcAg at a minimum cell number of 18 × 103 cells per well (Fig. 4). However, the designation of HBcAg-specific B cells as resting may be a misnomer (see below). The B cell nature of the APC function was confirmed by the radiation sensitivity of APC–T cell hybridoma activation. Assuming more than one HBcAg-specific B cell per well is required for T cell hybridoma activation, the results suggest a very high precursor frequency for HBcAg-specific B cells in naive mouse spleen.

Figure 4.

APC function of Percoll-isolated B cell fractions. Spleen cells from unprimed B10.S mice were depleted of T cells and fractionated on Percoll density gradients as indicated. Varying numbers (0.6–300 × 103) of nonirradiated or irradiated (2500R) whole spleen cells or Percoll gradient fractionated cells were used as APC and cultured with the I-As-restricted, HBcAg-specific T cell hybridoma 3E3–5G4 (1.2 × 104) and HBcAg (0.2 μg/ml). This HBcAg concentration was chosen to minimize non-B cell APC function. The minimum number of APC per well required to elicit three times the background (i.e., without HBcAg) level of IL-2 production by the T cell hybridoma is shown.

The HBcAg Induces Costimulatory Molecules on Naive B Cells.

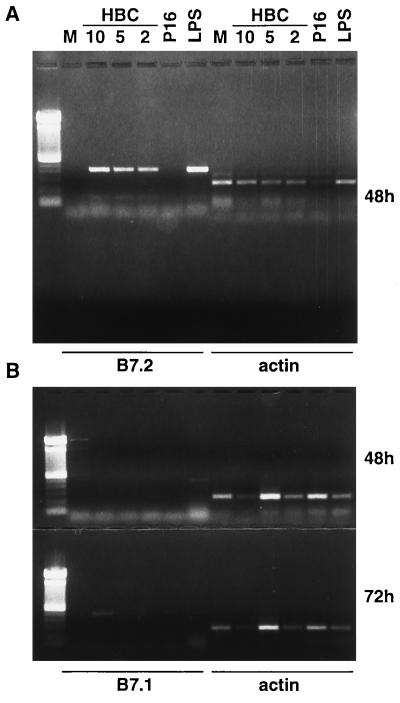

In addition to antigen uptake, processing, and presentation of peptide–major histocompatibility complexes, an effective APC must also express the costimulatory molecules necessary to deliver the second signal to a resting T cell (20). One important costimulatory molecule, CD28, binds its coreceptors, B7.1 and B7.2, on APC during TCR engagement leading to proliferation and cytokine gene expression (21, 22). Up-regulation of B7.1 and B7.2 correlates with the ability of B cells to costimulate T cells (20). Because resting HBcAg-specific B cells may function as APC for primary T cells (see Fig. 6), which do require costimulatory signals, as well as for T cell hybridomas, which do not require costimulation, we investigated the possibility that HBcAg may induce B7.1/B7.2 gene expression on naive B cells by binding to and cross-linking mIg. For this purpose, purified B cells from naive mice were cultured for 48–72 h with yeast-derived particulate HBcAg (10, 5, and 2 μg/ml) or with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10 μg/ml) as the positive control, and B7.1/B7.2 mRNA expression was assessed by RT-PCR. Culture of naive B cells with HBcAg for 48 h resulted in the induction of B7.2 mRNA at all three HBcAg concentrations, whereas P16 or media alone did not induce B7.2 at 48 h (Fig. 5A) or at 72 h (data not shown). The HBcAg did not induce B7.1 mRNA after 48 h as did LPS; however, after 72 h of culture the highest concentration of HBcAg did induce low level B7.1 mRNA expression (Fig. 5B). In a series of experiments using E. coli-derived recombinant proteins and naive B cells from LPS-nonresponsive mice (C3H/HeJ), similar results were obtained. Only HBcAg particles induced B7.2 and weak B7.1 mRNA expression in unprimed B cells after 48 or 72 h of culture, and P16, HBeAg, and HBV envelope particles (i.e., HBsAg) were unable to induce B7.2 or B7.1 mRNA (data not shown). Next, to determine whether B7.2 induction by the HBcAg was mediated through the B cell mIg receptor and was HBcAg-specific, anti-mIg or anti-HBc antibodies were included in the B cell cultures together with HBcAg or LPS, and B7.2 mRNA expression was monitored by RT-PCR (Fig. 3C). Similar to the effects these antibodies had on the ability of naive B cells to present HBcAg to T cell hybridomas, the induction of B7.2 mRNA in unprimed B cells by HBcAg was inhibited by the presence of anti-mIg Fab fragments or anti-HBc antibodies, whereas the induction of B7.2 mRNA by LPS was unaffected by the antibody treatments.

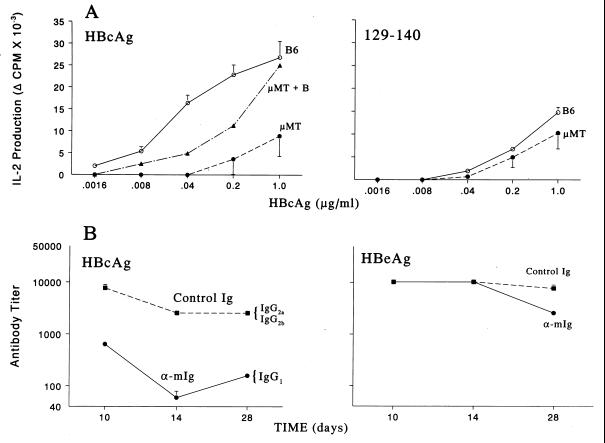

Figure 6.

B cell APC are required for efficient priming of Th cells and antibody production in vivo. (A) Groups of five wild-type B6 or B cell knockout μMT mice were immunized with HBcAg (Left) or peptide 129–140 (Right). Ten days later, draining popliteal lymph node cells were harvested, pooled, and cultured with media or HBcAg (.0016–1.0 μg/ml), and IL-2 levels in 24 h SN were determined by bioassay. In selected experiments unprimed B cells were added to μMT lymph node cells during in vitro culture to provide a source of B cell APC. This experiment was performed on three separate occasions, and the data represent mean values ± SD. [B6 > μMT; P < .05, Mann–Whitney (Left)]. (B) Groups of five (B10 × B10.S)F1 mice were treated with 0.5 mg of goat anti-mIg F(ab′)2 fragments (bivalent) or goat Ig as a control on days 0, 1, and 2, and immunized with HBcAg (.05 μg) in saline (Left) or HBeAg (10 μg) in saline (Right) on day 0. After immunization, sera were collected, pooled, and assayed for anti-HBc or anti-HBe antibodies by solid-phase ELISA (9). The data are expressed as antibody end-point titer representing the highest serum dilution that yielded an OD492 reading three times that of preimmunization sera. This experiment was performed twice, and mean values ± SD are shown.

Figure 5.

The HBcAg can induce B7.2 and B7.1 mRNA in unprimed B cells. Unprimed, splenic B cells derived from B10.S mice were cultured in media alone (M), with 3 concentrations of LPS-free, yeast-derived rHBcAg (kindly provided by P. Valenzuela, Chiron, Emeryville, CA) (10, 5, and 2 μg/ml), with P16 (10 μg/ml), or LPS (10 μg/ml). After 48 h and 72 h of culture, the B cells were harvested and the presence of B7.2 mRNA (A) and B7.1 mRNA (B) was determined by RT-PCR. The expected sizes of the amplified products were 496 bp for B7.1, 404 bp for B7.2, and 245 bp for β-actin. A 100-bp ladder was used as a DNA size marker.

HBcAg-Specific B Cells Function as APC in Vivo.

Because of the enhanced uptake and presentation of HBcAg by unprimed B cells and the ability of HBcAg to induce B7.1/B7.2 costimulatory molecules on naive HBcAg-specific B cells in vitro, it was reasonable to predict that HBcAg-specific B cells may serve an important APC function during the primary Th cell response to HBcAg in vivo. To address this issue, we examined HBcAg-specific Th cell priming in B cell knockout (μMT) or wild-type B6 mice by using HBcAg or peptide 129–140 as immunogens (Fig. 6A). The priming of Th cells (i.e., IL-2 production) specific for HBcAg was significantly impaired in the B cell knockout μMT mice when HBcAg was used as the immunogen. This defect was corrected by the addition of unprimed B cells (μMT + B) to the recall culture in vitro, indicating that naive B cells can present HBcAg to memory Th cells. However, the defect was only partially corrected by the addition of B cells in vitro, suggesting an important role for B cell APC in the priming of naive Th cells in vivo. The absence of B cells did not affect HBcAg-specific Th cell priming in μMT mice when peptide was used as the immunogen (Fig. 6A Right), suggesting that B cells are not involved in the presentation of peptide antigens to Th cells in vivo as previously observed (23). Usually, peptide immunogens do not prime a protein-specific Th cell response as efficiently as the protein itself (i.e., compare B6 mice immunized with HBcAg vs. 129–140, Fig. 6A). Note that the HBcAg particle and the peptide were equivalent as immunogens in μMT mice in terms of priming HBcAg-specific Th cells (i.e., compare Fig. 6A Left and Right), suggesting that B cell APC function may account for the major differences in Th cell priming observed for protein vs. peptide antigens. Another approach that revealed the importance of B cell APC function in the in vivo immune response to HBcAg was the use of goat anti-mIg in vivo as a means of blocking mIg-mediated antigen uptake. Mice treated with goat anti-mIg and injected with HBcAg (0.05 μg) in saline produced significantly less anti-HBc antibody as compared with control mice treated with goat Ig (Fig. 6B Left). Importantly, the anti-mIg treatment also shifted the subclass distribution of anti-HBc antibodies from IgG2a/IgG2b to an exclusive IgG1 response. The limited treatment (days 0, 1, and 2) with anti-mIg did not affect the antibody response to the nonparticulate HBeAg, ruling out nonspecific effects on antibody production (Fig. 6B Right). These data suggest that blocking B cell mIg-mediated uptake of HBcAg in vivo, and the subsequent presentation of HBcAg by non-B cell APC results in reduced antibody production, altered Ig switching, and possibly a shift in Th cell subset activation (i.e., from Th1 to Th2 cells).

DISCUSSION

A number of cell types including B cells can serve as APC for activated Th cells; however, this is not true for naive Th cells (24). The ability of activated or resting B cells to function as APC for primary T cells has been a controversial subject for a number of years (25–27). Although B cells possess antigen-specific mIg receptors, which can enhance antigen uptake and presentation 103- to 104-fold as compared with so-called professional APC (11, 16–18), the low precursor frequency, the activation state, and reduced costimulatory activity of resting B cells limit their ability to function as primary APC (28, 29) and may even result in tolerization rather than activation of T cells (27). It has been suggested that B cell antigen presentation can only activate naive T cells under unusual circumstances (28). Experimentally, primary B cell APC function has been demonstrated by manipulating either the antigen stimulus or the T cell or B cell repertoire. For example, polyclonal antigens such as rabbit anti-murine IgD that target 80% of B cells have been used to demonstrate B cell antigen presentation to rabbit Ig-specific T cells (17, 18). Transgenic TCR and/or BCR mice have been used as sources of antigen-specific Th cells or B cell APC to compensate for low precursor frequencies (26, 29, 30). Typically, unprimed B cells derived from “normal” mice are used as negative controls in these experimental systems and do not express B7.2 or perform as APC when pulsed with nominal antigens (26, 28–30).

In contrast, the HBcAg is a naturally occurring antigen that possesses a number of characteristics apparently sufficient to elicit efficient APC function even in unprimed B cells. For example, HBcAg is a particulate, multivalent, protein antigen capable of cross-linking mIg receptors and inducing T cell-independent antibody production (1). Second, mIg receptor-mediated uptake of HBcAg enhances naive B cell APC function 105-fold as compared with non-B cell APC. Third, cross-linking of mIg by HBcAg is sufficient to induce B7.2 and B7.1 costimulatory molecules on naive HBcAg-specific B cells. Last, a high precursor frequency of HBcAg-specific B cells exists in unprimed mouse spleen. Therefore, on encountering HBcAg in vivo or in vitro, a relatively high frequency of HBcAg-specific B cells bind and internalize the HBcAg via specific mIg receptors, and receptor cross-linking is sufficient to induce B7.1 and B7.2 costimulatory molecules. Limited B cell clonal expansion and differentiation can also occur before any T cell activation, as demonstrated by T cell-independent anti-HBc antibody production in athymic mice (1). Therefore, a large pool of activated, HBcAg-specific B cells capable of functioning as APC for naive, resting Th cells may assemble relatively quickly, which may explain the enhanced immunogenicity of HBcAg in mice, and during HBV infection in man.

Is the HBcAg unique among particulate and/or protein antigens in terms of eliciting B cell APC function in vivo? All particulate antigens do not have the characteristics of the HBcAg. For example, the HBsAg is a similar-sized particulate antigen but does not induce costimulatory molecules on naive B cells (data not shown), nor can HBsAg be presented to HBsAg-specific T cell hybridomas by unprimed splenic B cells (31). It has been suggested that naive B cells must be “primed” by antigen presented on follicular dendritic cells (FDC) within germinal centers (GC) before they can interact with T cells (32), and that repeating epitopes presented on the surface of FDC acquire the appropriate spacing to cross-link B cell mIg receptors (33). The unique structure of the HBcAg particle consisting of appropriately spaced protein spikes carrying repeating epitopes may bypass any requirement for B cell “priming” by FDC. Alternatively, presentation of the HBcAg may represent an extremely efficient example of the normal APC pathway for protein antigens. Many of the characteristics delineated for the HBcAg (i.e., high B cell precursor frequency) are more limiting in vitro than in vivo and may be compensated for by B cell activation or clonal expansion in specialized tissues in vivo [i.e., GC (26, 34)].

The implications of the current findings for HBV infection are notable. Maternal anti-HBc antibodies present in the neonate during vertical transmission of HBV may block B cell uptake of HBcAg and skew APC function toward less efficient MØ/DC cells, which may contribute to the high chronicity rates (i.e., ≈90%) in this population. Point mutations within the dominant HBcAg B cell epitopes may also circumvent B cell APC function in chronic patients. For example, mutant HBcAg particles with deletions of the dominant B cell epitopes (3) are not presented efficiently by naive splenic B cells to HBcAg-specific T cell hybridomas (data not shown). Last, the high levels of soluble anti-HBc antibodies present in the sera of chronic HBV patients may compete with B cell mIg receptor-mediated uptake of HBcAg, which may inhibit or skew ongoing Th cell activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. William Weigle for providing μMT mice, Dr. Matti Sällberg for helpful discussions, and Rene Lang for editorial assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI 20720 and is publication 10917-MB from The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBcAg, hepatitis B core antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; IL, interleukin; APC, antigen-presenting cell(s); SN, supernatant; MØ/DC, macrophage/dendritic cell; mIg, membrane Ig.

References

- 1.Milich D R, McLachlan A. Science. 1986;234:1398–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.3491425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milich D R, Schödel F, Hughes J L, Jones J E, Peterson D L. J Virol. 1997;71:2192–2201. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2192-2201.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schödel F, Moriarty A M, Peterson D L, Zheng J, Hughes J L, Will H, Leturcq D J, McGee J S, Milich D R. J Virol. 1992;66:106–114. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.106-114.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milich D R, McLachlan A, Thornton G B, Hughes J L. Nature (London) 1987;329:547–549. doi: 10.1038/329547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Böttcher B, Wynne S A, Crowther R A. Nature (London) 1997;386:88–91. doi: 10.1038/386088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway J F, Cheng N, Zlotnick A, Wingfield P T, Stahl S J, Steven A C. Nature (London) 1997;386:91–94. doi: 10.1038/386091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachmann M F, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3445–3451. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. Nature (London) 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schödel F, Peterson D, Zheng J, Jones J E, Hughes J L, Milich D R. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1332–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White J, Blackman M, Bill J, Kappler J, Marrack P, Gold D P, Born W J. J Immunol. 1989;145:1127–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas A K, Haber S, Rock K L. J Immunol. 1985;135:1661–1667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen C P, Ritchie S C, Hendris R, Linsley P S, Hathcock K S, Hodes R J, Lowry R P, Pearson T C. J Immunol. 1994;152:5208–5219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C, Gault A, Shen L, Nabavi N. J Immunol. 1994;152:4929–4936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen B E, Rosenthal A S, Paul W E. J Immunol. 1973;111:820–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celis E, Chang T W. Science. 1984;224:297–299. doi: 10.1126/science.6231724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanzavecchia A. Nature (London) 1985;314:537–539. doi: 10.1038/314537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesnut R, Grey H M. J Immunol. 1981;126:1075–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tony H P, Phillips N E, Parker D C. J Exp Med. 1985;162:1695–1704. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.5.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips N E, Parker D C. J Immunol. 1984;132:627–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janeway C A, Bottomly K. Cell. 1994;76:275–285. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linsley P S, Brady W, Grosmaire L, Aruffo A, Damle N K, Ledbetter J A. J Exp Med. 1991;173:721–729. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenschow D J, Su G H, Zuckerman L A, Nabavi N, Jellis C L, Gray G S, Miller J, Bluestone J A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11059–11064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Constant S, Sant’ Angelo D, Pasqualini T, Taylor T, Levin D, Flavell R, Bottomly K. J Immunol. 1995;154:4915–4923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashwell J D. J Immunol. 1988;140:2697–2704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janeway C A, Jr, Ron J, Katz M E. J Immunol. 1987;138:1051–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Constant S, Schweitzer N, West J, Ranney P, Bottomly K. J Immunol. 1995;155:3734–3741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lassila O, Vainio O, Matzinger P. Nature (London) 1988;334:253–256. doi: 10.1038/334253a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris S C, Lees A, Finkelman F D. J Immunol. 1994;152:3777–3785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho W Y, Cooke M P, Goodnow C C, Davis M M. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1539–1549. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenschow D J, Sperling A I, Cooke M P, Freeman G, Rhee L, Decker D C, Gray G, Nadler L M, Goodnow C C, Bluestone J A. J Immunol. 1994;153:1990–1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheerlinck J-P Y, Burssens G, Brys L, Michel A, Hauser P, De Baetselier P. Immunol. 1991;73:88–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosco-Vilbois M H, Gray D, Scheidegger D, Julius M. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2055–2066. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szakal A K, Gieringer R L, Kosco M H, Tew J G. J Immunol. 1985;134:1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y J, Zhang J, Lane P J L, Chan E Y T, MacLennan I C M. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2951–2958. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]