Abstract

Gasdermin-like (GSDML) belongs to the gasdermin-domain-containing protein family (GSDMDC family) that is involved in carcinogenesis and hearing impairment. However, the role of GSDML in carcinogenesis remains unclear. In this study, we identified four isoforms of GSDML gene. The primary and longest isoform GSDML1 is widely expressed in human cancer cell lines. GFP-GSDML1 fusion protein was localized predominantly in the nucleus of human breast cancer MCF7 and cervical cancer HeLa cells but exclusively in the cytoplasm of hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Importantly, immunohistochemistry analysis showed that the GSDML protein in the nuclei is expressed at a higher level in uterine cervix cancer tissues than in the adjacent cancer tissues and corresponding nonneoplastic tissues. Such significance was not observed in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues. Ectopic expression of GSDML1 enhanced the growth of cultured cells, whereas inhibition of its endogenous expression decreased proliferation. Furthermore, GSDML1 had significant effects on promoting bromodeoxyuridine incorporation in cells. However, GSDML1 could neither promote malignant transformation nor gain the ability of colony formation or carcinogenicity on nude mice. Collectively, these results suggest that GSDML can promote cell proliferation, and it might be correlated with carcinogenesis and progression of uterine cervix cancer.

Introduction

Gasdermin-domain-containing (GSDMDC) protein family, defined by a conserved gasdermin domain, includes five members, namely, DFNA5, DFNA5L, MLZE, GSDM, and GSDML [1–5]. The precise function of gasdermin domain still remains largely unclear. A deletion/insertion mutation of DFNA5 is associated with an autosomal dominant nonsyndromic hearing impairment form [1]. A decrease in DNFA5 mRNA expression level has also been found to contribute to acquired etoposide resistance in melanoma cells [6]. The expression of the DFNA5 gene can be strongly induced by p53, and ectopic expression of DFNA5 enhanced etoposide-induced cell death in the presence of p53 [7]. Moreover, DFNA5 has been identified as a target of epigenetic inactivation in gastric cancer [8]. MLZE is one of the genes whose expression is up-regulated during the acquisition of metastatic potential in melanoma cells [3]. GSDM is predominantly expressed in the upper gastrointestinal tract but is significantly suppressed in human gastric cancer cells, suggesting that the loss of human GSDM is required for the carcinogenesis of gastric tissue and that GSDM possesses an activity adverse to malignant transformation [4,9]. As human DFNA5L mRNA is widely expressed in human cancer tissues, DFNA5L might also be implicated in malignant potential of tumor cells [2]. As a new member of the GSDMDC family, the function of GSDML gene is still unknown, and needs further investigation. Mouse Gsdm1-Gsdm2-Gsdm gene cluster was predicted to be generated due to the triplication of mouse Gsdm gene, whereas human GSDML gene was predicted to be generated due to duplication of GSDM gene. The rodent ortholog of human GSDML has not been identified so far. In addition, evolutionary recombination hotspot around the GSDML-GSDM locus was closely linked to the oncogenomic recombination hotspot around the PPP1R1B-ERBB2-GRB7 amplicon. Because DFNA5, MLZE, GSDM, and DFNA5L have been implicated in the development and progression of cancer, GSDML was predicted to be associated with cancer [5], which lack experimental evidence until now.

To investigate whether GSDML is involved in the development or progression of some cancers, we have cloned and characterized GSDML gene and analyzed expression level of GSDML protein in uterine cervix cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma tissues by immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, we explore the function of GSDML by the overexpression or silence expression in various cell lines. Our study showed that subcellular localization of GSDML may influence its function of proliferation promotion and reveal the pathophysiological role of GSDML up-regulation in uterine cervix cancer. To our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the potential role for GSDML in cell growth and carcinogenesis of uterine cervix cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, Plasmid Construction, and Small Interference RNA

Human GSDML gene was amplified from human fetal liver cDNA library (Clontech, Terra Bella, CA). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was done using a pair of forward (5′-CCG CTC GAG CA ATG TTC AGC GTATTT G-3′) and reverse (5′-CGC GGATCC TTA GGA AGA GAC AGA GGT-3′) primers under the conditions of 94°C (60 seconds), 55°C (60 seconds), and 72°C (1 minute 20 seconds) for 30 cycles. Plasmid constructs were produced by general molecular biology procedures. The expression vector encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion GSDML protein was generated by inserting GSDML into pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech). GFP-tagged GSDML1-ΔNLS (242-261aa, predicted nuclear localization signal) was constructed by PCR and recombinant PCR, followed by subcloning into pEGFP-C1 vector. The expression vector for Myc-tagged GSDML was generated by inserting the fragment into pcDNA3.1/Myc-His(+)C (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All PCR-based constructions were verified by DNA sequencing, short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-GSDML (target sequence nt 578–596 GCCAAAGGGAAGTGACCAT) plasmid containing the neo expression cassette reform from RNAi-Ready-pSIREN-DNR-DsRed-Express (Clontech) as we have described previously [10]. The small interfering RNA (siRNA) against GSDML1 were designed and chemically synthesized (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Shanghai, China) for targeting coding regions (nt 570–588) of the GSDML1 gene as follows: siRNA-GSDML1 (5′-ACACAAGGGCCAAAGGGAAtt-3′ and 3′-tt UGUGUUCCCGGUUUCCCUU-5′). The sequence of negative control siRNA was 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUtt-3′ and 3′-ttAAGAGGCUUGCACAGUGCA-5′ (Cat. no. B01001; Shanghai GenePharma Co.).

Generation of Anti-GSDML Antibody

Rabbit polyclonal anti-GSDML antibodies and mouse monoclonal antibody were generated against epitopic peptides (64–168aa) from the GSDML protein sequence. Using the pEGFP-GSDML as template, PCR was performed with the following set of primers: 5′- CGC GGATCC AT ACA GAT GGG GAC AAG TGG TTA G -3′ and 5′- CCG CTC GAG TTC CTC CTT TAC CGT CTC CAG A -3′. The PCR-amplified cDNA fragment was excised and ligated into the BamHI-XhoI sites of pET28c vector (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The plasmid was transformed to Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX), and the expression of the 6 x His-tagged GSDML was induced with 0.05 mM isopropylthiogalactoside. The bacteria were lysed by sonication, and the GSDML tagged with 6 x His was extracted from the insoluble pellet with 8 M urea, 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, and 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Extracted protein was applied to Talon resin and was eluted with excess imidazole. White rabbits and BALB/c mouse were immunized with the purified protein to produce polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies, respectively. The polyclonal antibodies could detect denatured GSDML 1, 2, 3, and 4 in immunoblots and the native protein in immunohistochemistry. The monoclonal antibody could detect the native protein in immunofluorescence experiments.

Cell Culture and Transfections

Cell lines HepG2, MCF7, T47D, Ishikawa, MGC803, N87, HeLa, SW480, LoVo, SACC-83, ACC-2 [11], ACC-M, A549, Glc-82, U2OS, HEK293, HEK293T Chang, and CHO-K1 were cultured at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT) containing 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. H1299, HCT-15, HNE1, Jurkat, MOLT-4, K-562, and HL-60 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. All mammalian cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). G418 was from Invitrogen and was used to screen stable transfectants as we have described previously [12].

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the 16 indicated cell lines using Trizol (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification was performed using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). The specific primers used in the PCR reactions were GAPDH (forward primer 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′, reverse primer 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′) and GSDML (forward primer 5′-ATGCCGGCACTACACAACAG-3′, reverse primer 5′-CACTTAGCGAGGGAGTTTAG-3′, amplification from nt 144 to 809). Polymerase chain reaction was performed under the conditions of 94°C (40 seconds), 55°C (40 seconds), and 72°C (50 seconds) for 30 cycles for GAPDH and for 35 cycles for GSDML. The PCR products were separated in 2% agarose gels.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were washed in PBS and lysed in modified lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Tween-20, 0.2% NP-40, and 10% glycerol] with freshly added protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 1 mM NaF, and 0.1 mg/ml PMSF as described previously [12]. Western blot analysis was performed with anti-GSDML rabbit polyclonal antibody or mouse monoclonal antibody and then the appropriate secondary antibody, followed by detection with SuperSignal chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Subcellular Localization Analysis

For subcellular localization analysis, GSDML 1, 2, 3, and 4 and GSDML1-ΔNLS were cloned into the vector pEGFP-C1 as described previously. The resulting GFP-GSDMLs and the GFP-GSDML1-ΔNLS were transfected into MCF7 cells by Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours before examination with a fluorescence microscope to determine the subcellular location. In addition, HeLa and HepG2 cells were used to examine subcellular localization of GFP-GSDML1. To explore subcellular localization of endogenous GSDML, MCF7, HeLa, HepG2, and LoVo cells were seeded in 35-mm plate and were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes and then in 0.1% PBST (containing 0.5% Triton X-100) for 15 minutes. Further processing included incubating cells in 5% BSA for 10 minutes before incubations with anti-GSDML mouse monoclonal or rabbit polyclonal antibody for 3 hours at 37°C and with flourescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat antimouse or goat antirabbit secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at the dilution of 1:200 for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were analyzed in PBS when the nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Fluorescence images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Furthermore, Myc-GSDML1, 2, 3, and 4 were each transfected into MCF7 cells and analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody to validate the localization results of GFP-GSDMLs.

Tissue Microarray Construction, Immunostaining and Statistics Analysis

Tissue microarrays of human uterine cervix cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma were purchased from Shaanxi Chao Ying Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China. Each of the uterine cervix cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma tissue microarrays was composed of 21 couples of cancer tissues, adjacent cancer tissues, and corresponding non-neoplastic tissues. Data about tumor histologic type and differentiation have been recorded prospectively for these specimens.

Immunohistochemistry analysis was performed with a standard avidin/biotin peroxidase method with an anti-GSDML rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:200 dilution). Briefly, 4-µm-thick array sections were dewaxed with xylene (twice for 10 minutes), rehydrated through graded alcohol (three times for 10 seconds), and immersed in methanol containing 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Heat-induced epitope retrieval consisting of 2 minutes of microwave treatment at high power in pH 6.0 citrate buffer (0.01 M) was necessary with the anti-GSDML rabbit polyclonal antibody. Endogenous avidin/biotin binding was blocked using an avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories, Servion, Switzerland), and sections were treated with 100 µl of normal rabbit serum for 10 minutes to block nonspecific binding of the primary antibody. Sections were then incubated with 100 µl of primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Primary antibody was omitted from negative control sections, which were incubated in dilute normal rabbit serum. After washing with 0.1% Tween-PBS twice, sections were incubated with 100 µl of biotinylated antirabbit immunoglobulin (DAKO Ltd., Glostrup, Denmark) diluted 1:100 for 12 minutes, followed by 100 µl of preformed streptavidin biotin/horseradish peroxidase complex (DAKO) for 12 minutes at room temperature. Staining was finally developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAKO). The slides were finally counterstained with hematoxylin and washed before passing through serial alcohol and xylene baths. Slides were finally dried and mounted with DPX (a mixture of disterene, plasticizer, and xylene; Sigma).

Evaluation of the staining was carried out by two pathologists, who were blinded to the clinicopathologic data, with a consensus decision in all cases. For each antigen, tumors were classified into three groups with regard to staining intensity: negative, weakly positive, and positive. All tissue samples on the array were used for comparisons of GSDML overexpression. Contingency table analysis and Fisher tests were used to study the relationship between cancer, adjacent cancer tissues, corresponding nonneoplastic tissues with cancers, and GSDML expression.

Measurement the Cell Growth

To study the effect of GSDML gene on cell proliferation, the pcDNA3.1 (+) vector control and the pcDNA3.1 (+)/GSDML1 mammalian expression construct were transfected into Chinese hamster ovarian cells (CHO-K1). G418 was used to obtain the neomycin-resistant transformants that indicated that the vector was present in the CHO-K1 cells. Control pooled clones and three individual GSDML1 clones were designed for the experiments in this study. CHO-K1 cells in the log phase were trypsinized and seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 5 x 103 cells/well. Cell proliferation was detected by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetric method every 24 hours in four wells for six successive days to compose the growth curve in vitro. The units of absorption (UA) were measured with Microplate Photometer Analyzer (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT) at a wavelength of 490 nm. In addition, HeLa and HepG2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 x 103 cells/well and were transfected with negative control siRNA and GSDML 1-siRNA, respectively. Cell growth curve was measured as described previously.

Cell Proliferation Assay

For measure DNA synthesis rates, the pcDNA3.1(+) vector control and three independent pcDNA3.1(+)/GSDML1 stably transfected CHO-K1 cell strains were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 x 104 cells/well for 24 hours. Incubation of cells with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) for 18 hours followed by immunodetection of incorporated BrdU label. The labeling solution was removed, and 200 µl of FixDenat (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) solution was added and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. After removing FixDenat, 100 µl of anti-BrdU-POD solution was added and incubated for 90 minutes at room temperature. After washing three times with 300 µl/well of washing buffer, the 100 µl of tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate solution (Boshide Tech, Ltd., Wuhan, China) was added and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature until color development was sufficient for photometric detection. The reaction was stopped with the addition of a TMB stop solution (100 µl). The absorbance of the samples was measured with an ELISA reader at 450 nm within 5 minutes after adding the stop solution.

Clone Formation Test

HeLa and HepG2 cells were seeded in 35-mm plates and transfected with control shRNA and GSDML shRNA plasmid containing the neo expression cassette and selected with 800 mg/ml G418 for 20 days and were then fixed with methanol and stained by 0.2% crystal violet.

Colony-Forming Efficiency in Soft Agar

One milliliter of 0.6% agarose in high-fertility culture medium was allowed to solidify in 35-mm culture dishes. These were overlaid with 1 ml of 0.3% agarose containing 1 x 104 cells/ml in middle-fertility culture medium. One milliliter of low-fertility culture medium was added to each well the next day. Cells from different stably transfected cell strains were incubated for 2 weeks at 37°C. The cell colonies (more than 15 cells) were counted under the microscope. The average of three independent experiments was shown.

Tumorigenesis Ability on Nude Mice Models

Eight of 4-week-old NIH athymic mice (purchased from the Institute for Experimental Animals, Peking Union Medical College, China) were maintained in the pathogen-free environment and divided into two groups. Each group consisted of four animals receiving pcDNA3.1(+) empty vector control and pcDNA3.1(+)/GSDML1 stably transfected CHO-K1 cell line separately. The cell suspensions were made in Hank's balanced salt solution, and 1 x 107 viable cells/0.2 ml was injected subcutaneously in the back of the nude mice.

Results

Bioinformatic Analysis of GSDML

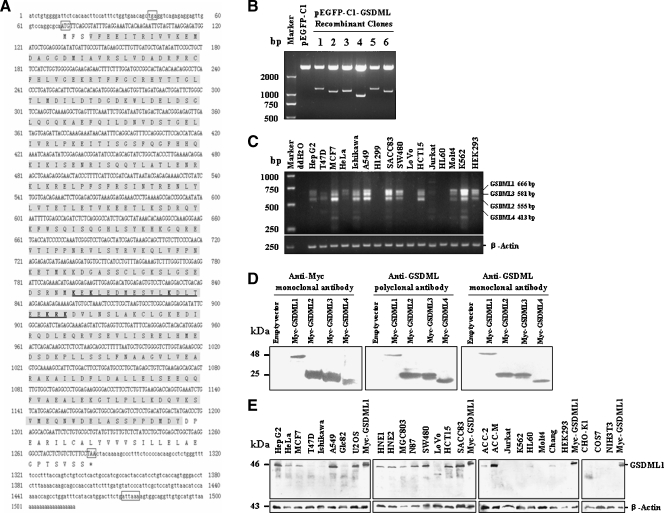

The full-length cDNA (Figure 1A) was 1518-bp long (GenBank Accession No. AK000409) and contained an open reading frame from nucleotide 72 to nucleotide 1283 capable of encoding a 403-amino acid polypeptide with a predicted molecular mass of 46 kDa. The 5′-noncoding region of GSDML was 71 bp in length, and the 3′-non-coding region was 235 bp in length. The 3′-terminus of the sequence contained a typical poly(A) addition signal, ATTAAA, which precedes multiple A nucleotides at the end of the sequence. The initiating ATG codon (nucleotides 72–74) is preceded by a TGA stop codon triplet upstream and conformed to a consensus initiation sequence. GSDML contains a gasdermin domain (amino acids 4–374), and a putative nuclear localization signal (NLS) was found within the gasdermin domain (242KEKLEDMESVLKDLTEEKRK261).

Figure 1.

Identification and characterization of GSDML. (A) Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of the GSDML. Top indicates nucleotide sequence; bottom, predicted amino acid sequence; numbers, the nucleotide residues and the amino acid residues. The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions are lower-case character. The initiating ATG codon (nucleotides 72–74) is preceded by one in-frame TGA stop codon. The coding sequence ends at nucleotide 1284 followed by TAA. The three codons and a classic polyadenylation signal are boxed. The amino acids comprising the gasdermin domain are in shaded. The sequence of a putative nuclear localization signal is underlined and six basic amino acids (K/R) are in bold. (B) The recombinant plasmids of human GSDML from human fetal liver cDNA library were identified by restriction enzyme analysis. pEGFP-C1 empty vector (lane 2) and six recombinant plasmids selected randomly (lanes 3–8) were digested with restriction enzymes (BamHI, XhoI). (C) Expression detection of GSDML isoforms in 15 human cancer cell lines and in human normal HEK293 cell by RT-PCR. ddH2O was used as the negative control of template. β-Actin levels were analyzed and shown as an internal control. (D) Characterization of anti-GSDML rabbit polyclonal antibody and mouse monoclonal antibody. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from CHO-K1 cells expressing pcDNA3.1(+) empty vector and pcDNA3.1(+)/GSDML 1, 2, 3, and 4. These samples were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE, probed with anti-myc mouse monoclonal antibody (left), anti-GSDML rabbit polyclonal antibody (middle), or anti-GSDML mouse monoclonal antibody (right). (E) Expression of endogenous GSDML proteins in 24 kinds of cell lines by Western blot with anti-GSDML polyclonal antibody. β-Actin levels were analyzed and shown as an internal control.

Cloning of GSDML Gene

Human GSDML gene was cloned from human fetal liver cDNA library. Interestingly, different-length DNA fragments were observed (Figure 1B), and the insert fragments were sequenced to be 1212, 1100, 1127, and 958 bp encoding 403, 203, 200, and 183 amino acid polypeptides, respectively. We thus named them GSDML1, GSDML2, GSDML3, and GSDML4 (GenBank Accession Nos. EU526753, EU526754, EU526755, and EU526756). Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of four isoforms of GSDML were aligned by CLUSTAL W (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw/) (Figure W1).

Analysis of GSDML Expression in 16 Types of Cell Lines

Total RNA was extracted from 16 cell lines including 15 types of cancer cell lines and HEK293 human embryonic kidney cells. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction amplification was performed to detect the expression of GSDML. Specific primers were designed to detect each of these four isoforms of GSDML (666, 555, 581, and 413 bp corresponding to GSDML 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively). Except for H1299, LoVo, and HL60, all examined cell lines showed the expression of GSDML isoforms (Figure 1C).

Western Blot Analysis of Endogenous GSDML in 24 Cell Lines

To detect endogenous GSDML proteins, anti-GSDML polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies were generated. All four ectopic expressed isoforms of GSDML could be detected by rabbit anti-GSDML polyclonal antibody and mouse anti-GSDML monoclonal antibody (Figure 1D). Using the specific anti-GSDML polyclonal antibody, we observed that GSDML 1 is widely expressed in the human cancer cell lines we examined (except Jurkat, Molt4, HL60, and HEK293), whereas the three short isoforms of GSDML could not be detected remarkably in the total 24 cell lines (Figure 1E). Notably, GSDML protein is expressed at a higher level in the metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) cell line ACC-M than in the nonmetastatic cell line ACC-2.

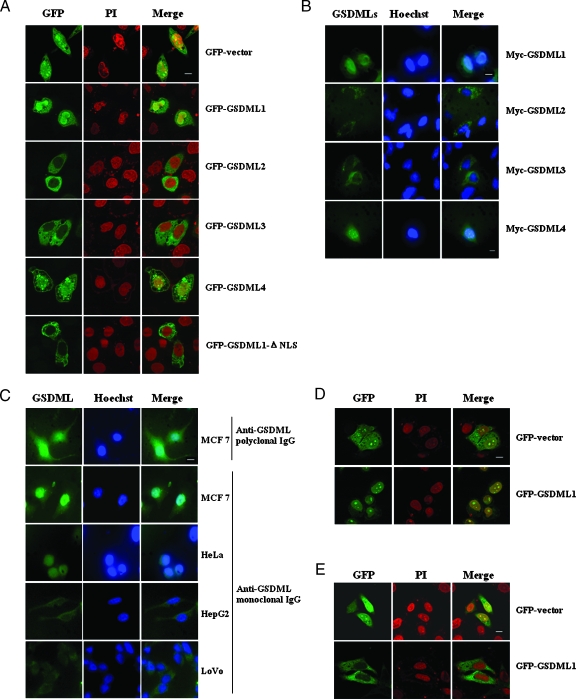

Subcellular Localization Analysis of GSDML

As shown in Figure 2A, GFP-GSDML1 protein was localized primarily in the nucleus and partly in the cytoplasm, whereas GFP-GSDML 2 and 3 were distributed in the cytoplasm. We also noted that in some cells, the transfection of GFP-GSDML1 seems to promote rounding of cells, and therefore, the fluorescence signal appears rounded. Sequence analysis showed that a basic amino acid-rich sequence KEKLEDMESVLKDLTEEKRK (242–261aa, basic residues are underlined) is predicted to be the putative NLS of GSDML. To verify this hypothesis, GFP-GSDML1-ΔNLS was constructed, and we observed that GFP-GSDML1-ΔNLS was distributed thoroughly in the cytoplasm. These results suggest that this sequence is indeed required for the nuclear localization of GSDML1. Although lacking the NLS within GSDML1, GFP-GSDML4 could be still localized primarily in the nucleus and partly in the cytoplasm (vesicular staining) or plasma membrane. We considered that newly formed basic amino acid-rich sequence by exon-skipping frameshift among the C-terminal of GSDML4 protein might play a role in its nuclear localization. To confirm the conclusions of the localization of GFP-tagged GSDML isoforms, myc-tagged GSDMLs were expressed in MCF7 cells, and their subcellular localization was determined by indirect immunofluorescence analysis with anti-myc antibody. The results coincided with those of GFP-GSDMLs (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization analysis of GSDML. (A) The GFP empty vector, GFP-GSDML 1,2,3, and 4 and GFP-GSDML-ΔNLS, were each transfected into MCF7 cells. Twenty-four hours later, cell nuclei were stained with PI (red), and fluorescence was visualized using a confocal microscope and images were captured and merged. Scale bar, 10µm. (B) Indirect immunofluorescence analysis with anti-myc antibodies (left panels) was performed to analyze the localization of GSDML after transfecting MCF7 cells with myc-GSDML 1,2,3, and 4. Hoechst (blue) staining (middle panels) indicates the location of nuclei in each field. The fluorescence was visualized using fluorescence microscope, and images were captured and merged (right panels). (C) Indirect immunofluorescence analysis with anti-GSDML polyclonal or monoclonal (left panels) was performed to determine the localization of endogenous GSDML in the indicated cells. (D and E) GFP-GSDML1 was transfected into HeLa (D) and HepG2 (E) cells, respectively. Twenty-four hours later, cell nuclei were stained with PI (red), and the fluorescence was visualized using confocal microscope and images were captured and merged.

We next investigated the subcellular localization of the endogenous GSDML protein. In MCF7 breast cancer cells, endogenous GSDML was localized mainly in the nucleus and partly in the cytoplasm as determined by indirect immunostaining with anti-GSDML polyclonal antibody and confirmed by anti-GSDML monoclonal antibody (Figure 2C, top two panels). In addition, HeLa, HepG2, and LoVo cell lines were also applied to subcellular localization analysis of endogenous GSDML. Surprisingly, although GSDML was in the nucleus of HeLa cervix cancer cells (Figure 2C, middle panels), which was similar to that in MCF7 cells, endogenous GSDML was exclusively cytoplasmic in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells and LoVo colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (Figure 2C, bottom two panels). Consistent with the endogenous data, GFP-tagged GSDML1 protein was also localized in nucleus of HeLa cells (Figure 2D) but exclusively in the cytoplasm of HepG2 cells (Figure 2E). These results suggested that the localization of GSDML 1 not only was determined by nuclear localization signal but was also dependent of tissue and cell types. Therefore, we next explore whether GSDML is involved in carcinogenesis of uterine cervix cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma.

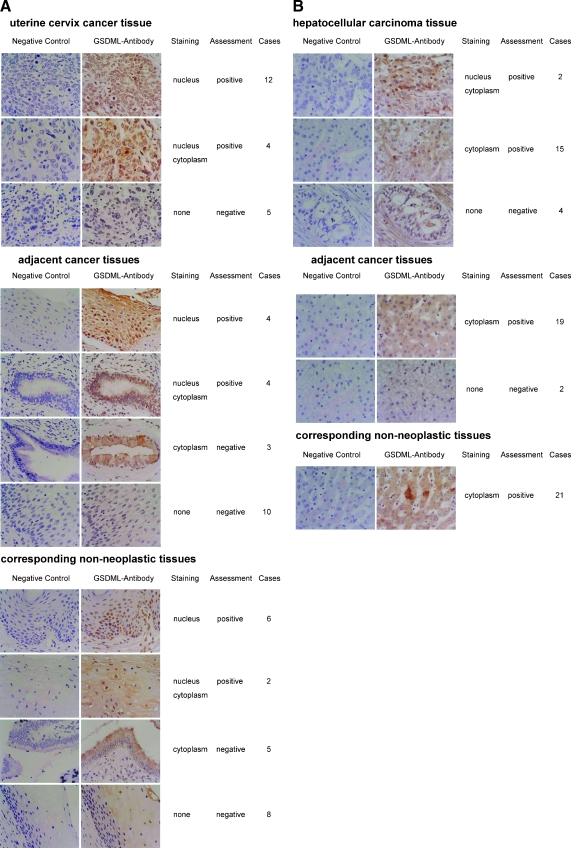

Correlation of Clinical Features with GSDML Expression

According to exogenous GFP-GSDML1 localized in the nucleus of HeLa cells, GSDML expression in the nucleus (including exclusively and partially nuclear) was considered as GSDML-positive, whereas expression in the cytoplasm or undetectable expression was considered as GSDML-negative. Among 21 uterine cervix cancer samples tested, 16 (76.2%) were GSDML-positive and 5 (23.8%) were GSDML-negative. Among 21 adjacent cancer tissues, 8 (38%) were GSDML-positive and 13 (61.9%) were GSDML-negative. Among 21 corresponding nonneoplastic tissues with cancers, 8 (38%) were GSDML-positive and 13 (61.9%) were GSDML-negative. Representative examples of GSDML-positive and -negative tumors are shown in Figure 3A. Statistical analysis was done to determine whether a possible correlation occurred between GSDML expression and clinical variables (Table 1). Immunohistochemistry with uterine cervix cancer tissue microarray revealed that the number of GSDML-positive cases was significantly larger in uterine cervix cancer than in adjacent cancer tissues (P < .05) and in corresponding nonneoplastic tissues with cancers (P < .05). Among 21 adjacent cancer tissues and 21 corresponding nonneoplastic tissues with cancers, there are 27 cervicitis (including two atypical hyperplasia), 1 cancer tissue, and 14 normal tissues. Nuclear staining of GSDML was found in 72.7% (16/22) of the cancer samples, in 42.3% (11/26) of cervicitis samples, and in 33.3% (5/15) of normal samples. GSDML protein levels were significantly higher in uterine cervix cancer tissue than in cervicitis (P < .05) and in normal tissue (P < .05).

Figure 3.

GSDML protein expression in uterine cervix cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma tissue microarrays. (A) Immunohistochemistry staining of GSDML expression in uterine cervix cancer (top), adjacent cancer tissues (middle), and corresponding nonneoplastic tissues (bottom). Immunohistochemistry analyses with negative control are shown in the left panels and with antibodies against GSDML are in the right panels. The expression of GSDML in nucleus was considered GSDML-positive, whereas expression in cytoplasm or no expression was considered GSDML-negative. Original magnification, x400. (B) Immunohistochemistry staining of GSDML expression in hepatocellular carcinoma (top), adjacent cancer tissues (middle), and corresponding nonneoplastic tissues (bottom). The experiments were performed and the results were shown similar to (A).

Table 1.

Relationship between Expression Levels of GSDML and Uterine Cervix Cancer.

| Clinical Characteristics | GSDL-Negative | GSDML-Positive | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | |||

| Cancer tissues | 5 | 16 | |

| Adjacent cancer tissues | 13 | 8 | .028* |

| Corresponding nonneoplastic tissues with cancers | 13 | 8 | .028* |

| Histopathologic type | |||

| Cancer | 6 | 16 | |

| Cervicitis | 15 | 11 | .045* |

| Normal | 10 | 5 | .017* |

Statistically significant.

Hepatocellular carcinoma patients were then further analyzed. Among 21 hepatocellular carcinoma patients, 2 cases (9.5%) were nuclear staining, 15 cases (71.4%) were cytoplasm staining, and 4 cases (19%) were none staining. All of 21 adjacent cancer tissues were cytoplasm staining (100%). Among 21 corresponding nonneoplastic tissues with cancers, 19 cases (90.5%) were cytoplasm staining and 2 cases (9.5%) were none staining. According to exogenous GFP-GSDML1 localized in the cytoplasm of HepG2 cells, the expression of GSDML in the cytoplasm and/or in the nucleus was considered GSDML-positive (Figure 3B). Statistical analysis was done to determine whether a possible correlation occurred between GSDML expression and clinical variables (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference between the expression levels in the hepatocellular carcinoma, adjacent cancer, and the corresponding nonneoplastic tissues. Overexpression of GSDML was found in 81% (17/21) of the cancer samples, in 100% (14/14) of hepatic cirrhosis samples, in 100% (9/9) of inflammation/hyperplasia/adipose degeneration samples, and in 89.5% (17/19) of normal samples. There was no statistically significant difference between the expression levels in the hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic cirrhosis, inflammation/hyperplasia/adipose degeneration, and normal tissue (P > .05).

Table 2.

Relationship between Expression Levels of GSDML and Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

| Clinical Characteristics | GSDML-Negative | GSDML-Positive | P |

| Sample | |||

| Cancer tissues | 4 | 17 | |

| Adjacent cancer tissues | 2 | 19 | .663 |

| Corresponding nonneoplastic tissues with cancers | 0 | 21 | .107 |

| Histopathologic type | |||

| Cancer | 4 | 17 | |

| Cirrhosis | 0 | 14 | .133 |

| Inflammation, hyperplasia, or adipose degeneration | 0 | 9 | .114 |

| Normal | 2 | 17 | .664 |

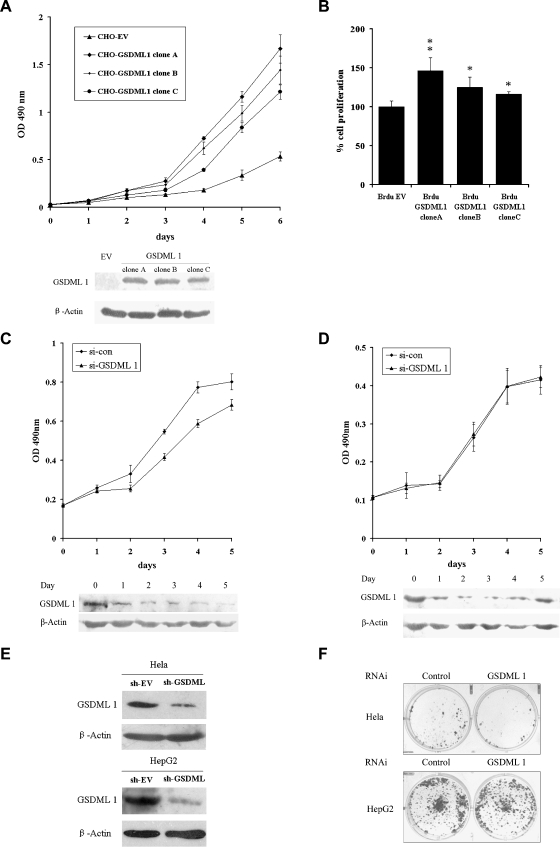

GSDML Stimulates Cell Proliferation of Ovarian and Cervix Cancer Cell Lines

Next, we investigated whether GSDML1 had any effects on cell growth. To prevent the interference of endogenous human GSDML proteins, Chinese hamster ovarian cells (CHO-K1) without endogenous GSDML expression (Figure W2A) were used instead of HeLa cells to screen GSDML 1 stably expressing transfectants. GFP-GSDML1 was localized predominantly in the nucleus and also seen in the cytoplasm (Figure W2B), which was similar to that in HeLa cells. Stable transfection of GSDML1 promoted the cell growth in CHO-K1 cells (Figure 4A). The promotion became obvious from the third day and increased thereafter. There was a significant difference between the three individual GSDML1-expressing cells and the empty vector control group (P < .01).

Figure 4.

Effects of overexpression and knock down of GSDML on cell proliferation. (A) Growth rates of CHO-K1 cells stably transfected with either GSDML1 expression vector (CHO-GSDML1) or empty vector (CHO-EV) were measured by MTT assays. Points indicate mean of quadruplicate samples; bars, SD. Western blot analysis of the indicated proteins in CHO-GSDML1 and CHO-EV cells are shown below to confirm the expression. (B) Proliferation of CHO-K1 cells stably transfected with either GSDML1 expression vector (CHO-GSDML1) or empty vector (CHO-EV) was measured by BrdU incorporation. Columns indicate means of three independent experiments; bars, SD. **P < .01; *P < .05, statistically significant. (C and D) MTT assays. Growth rates of HeLa (C) and HepG2 (D) cells with transfection of GSDML1 siRNA and negative control siRNA. Points indicate mean of quadruplicate samples; bars, SD. Cells were harvested daily and analyzed by Western blot for GSDML1 expression. β-Actin was used as control for equal loading and siRNA specificity. (E) HeLa and HepG2 cells were transfected with either short hairpin RNA (shRNA) construct targeting GSDML1 gene (sh-GSDML) or shRNA empty vector (sh-EV), respectively. Thirty-six hours later, cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blot for GSDML1 expression. β-Actin was used as control for equal loading and shRNA specificity. (F) Forty-eight hours after transfection with either sh-GSDML1 or sh-EV, the HeLa and HepG2 cells were selected with G418 for 3 weeks.

To analyze further the effect of GSDML on cellular proliferation, BrdU incorporation assay was applied to measure the rates of DNA synthesis. GSDML1 had significant effects on promoting BrdU incorporation in CHO-K1 cells (clone A, P < .01; clones B and C, P < .05; Figure 4B).

We next used siRNA to evaluate the role of endogenous GSDML in the cell proliferation of HeLa and HepG2 cell lines. We identified a siRNA to be efficient in inhibiting GSDML in HeLa and HepG2. MTT assays showed that HeLa cells transfected with GSDML siRNA exhibited a significant decrease in cell growth compared with those with the negative control siRNA (Figure 4C). By contrast, in HepG2 cells, there was no significant difference in cell growth between the cells transfected with the GSDML1 siRNA and with the negative control siRNA (Figure 4D).

Furthermore, knock down of GSDML1 in HeLa cells showed that the number of G418-resistant colonies was significantly reduced, suggesting that GSDML was essential for cell growth and that its deficiency could result in growth retardation (Figure 4E). Similar to the previously mentioned conclusions, this effect could not be observed in HepG2 cells (Figure 4F).

GSDML1 Could Not Induce Malignant Transformation of CHO-K1 Cells

Evaluation of colony-forming efficiency in soft agar and carcinogenic ability on nude mice models was performed to determine whether GSDML1 possesses a potency of malignant transformation. Both CHO-K1 cells transfected with GSDML1 and control vector failed to form colony in soft agar. Coincidentally, the CHO-K1 cells transfected with GSDML 1 and control vector into the nude mice failed to produce tumors (Table 3).

Table 3.

CHO Cell Lines Colony-Forming and Tumorigenic Ability.

| Stable Cell Lines | Colony-Forming Units | Animals with Tumor at 21 days |

| Empty vector | 0/3* | 0/4† |

| GSDML 1 | 0/3* | 0/4† |

Number of colony-forming units/number of planted wells.

Number of animals with subcutaneous tumor/number of injected animals.

Discussion

The GSDMDC family is a novel protein superfamily, characterizing a gasdermin domain in all of members. Although a few studies indicated that the GSDMDC family had important physiological functions in development, tumorigenesis, and genetic disease with deafness and hair loss phenotype, the molecular structure and precise biologic function of GSDMDC family are still unclear [1–5,7,8,13–15]. The relationship between GSDMDC family members and carcinogenesis has been suggested. The DFNA5 and GSDM have a negative correlation with carcinogenesis, whereas the MLZE and DFNA5L have a positive correlation with carcinogenesis [2–4,7,8]. More studies have focused on the DFNA5 gene because it is one of the disease genes with an autosomal-dominant nonsyndromic hearing impairment and it is associated with melanoma, breast cancer, and gastric cancer [6–8]. Morpholino antisense nucleotide knock down of DFNA5 function in zebrafish leads to the disorganization of the developing semicircular canals and to the reduction of pharyngeal cartilage, indicating that DFNA5 is required for the normal development of the ear [16]. Morphologic studies demonstrated significant differences in the number of fourth-row outer hair cells between Dfna5-/- mice and their wild type littermates [13]. Extensive expression analysis revealed an exclusive expression of the GSDM gene in the epithelium of the skin and gastrointestinal tract in a highly tissue-specific manner. Loss of the expression of the human GSDM is required for the carcinogenesis of gastric tissue, and this gene has an activity adverse to malignant transformation of cells [4,9]. Gsdm3 (mouse homolog of GSDM) mutations cause alopecia in Rco2, Re(den), and Bsk mice, showing that the murine Gsdm3 gene is required for the normal development and cycling of the dorsal hair follicle, the epidermis, and the development of sebaceous glands from the pilosebaceous unit [14]. Pejvakin gene, a newly identified member of the GSDMDC family, in which two missense mutations cause nonsyndromic recessive deafness (DFNB59) by affecting the function of auditory neurons [17]. Another study has described a premature stop codon of pejvakin gene, causing outer hair cell defects and leading to progressive hearing loss, suggesting that pejvakin genes control the development and function of mechanosensory hair cells and cause deafness [18]. Current data suggest that physiological functions of the GSDMDC family are possibly involved in the development and differentiation of epithelial cells.

To find new cancer-associated genes in the GSDMDC family, we cloned GSDML gene from a human fetal liver cDNA library. As a novel member of the GSDMDC family, however, the function of the GSDML gene remains unknown. The GSDML gene is mapped to 17q21.2, a region that contains the erbB2 gene and is often amplified in malignant tumors [5]. The full-length cDNA of GSDML is 1518 bp long and contains an open reading frame from nucleotide 72 to nucleotide 1283 capable of encoding a 403-amino acid polypeptide with a predicted molecular mass of 46 kDa. GSDML protein contains a gasdermin domain within which a putative nuclear localizing signal was identified (Figure 2). Interestingly, we also isolated three short splicing isoforms of GSDML. The solitary long terminal repeats (LTRs) of human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) have been found to serve as alternative promoters of the GSDML gene [19]. The HERV-H LTR element on the GSDML gene was integrated into the genome of hominoid primates. Such an LTR element seems to be active as the dominant promoter in human tissues and cancer cells. Western blot analysis with the specific anti-GSDML polyclonal antibody showed that GSDML1 is widely expressed in human cancer cell lines we examined, whereas the three short isoforms of GSDML were not detected clearly in all the 24 cell lines tested. The nonsense-mediated decay pathway is an mRNA surveillance mechanism that limits the translation of mRNA with premature termination codons [20,21]. Alternative splicing of GSDML is subject to the mode of exon-skipping frameshift with premature termination codons. We presumed that the three short isoforms of the GSDML protein were inhibited by nonsense-mediated decay pathway. Hence, the full-length GSDML1 protein became the focal point of study. Nguyen et al. [22] investigated the differences in gene expression profiles between primary tumors of oral squamous cell carcinoma that had metastasized to cervical lymph nodes and those that had not metastasized in the hope of finding new biomarkers to serve for diagnosis and treatment of oral cavity cancer by microarray technology. Ultimately, eight candidate genes expressed differentially were selected to achieve the minimum error rate. Among them, the GSDML gene is one of six up-regulated genes in oral cavity cancer with the cervical lymph node metastasis. Correspondingly, the expression levels of ACC-M (adenoid cystic carcinoma cell clones highly metastatic to the lung) are significantly higher than that in ACC-2 (adenoid cystic carcinoma cell line, ACC-2) in our study (Figure 1D). Overexpression of GSDML in ACC-M suggested that GSDML may be involved in tumor metastasis.

In the present investigation, we have shown that the subcellular localization of GSDML1 was different in different tissues and cell lines. GFP-GSDML1 localized predominantly in the nucleus of HeLa cells, but unexpectedly, localized in the cytoplasm of HepG2 cells. Interestingly, nuclei staining of the GSDML protein was expressed at a higher level in uterine cervix cancer tissue than in the adjacent cancer tissues and corresponding nonneoplastic tissues through immunohistochemistry analysis of cancer tissue microarray (Figure 3A). In addition, nuclei staining levels of GSDML protein were significantly higher in uterine cervix cancer tissue than in cervicitis and normal tissue. As in most hepatocellular tissues samples, GSDML was cytoplasm staining; such difference has not been observed in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues microarray (Figure 3B), suggesting that the effect of GSDML may be different in different tissues as determined by subcellular localization. Among 63 hepatic tissue samples, the only 2 cases of nuclei staining are all hepatocellular carcinoma. We observed that there are still a few proportions of GSDML-positive in cervicitis and normal tissue, suggesting that GSDML could be important as an evaluation indicator in onset risk during the normal to cervicitis to lesion precancerous to uterine cervix cancer transition process.

We found exogenous GSDML1-stimulated proliferation of CHO-K1 cells by the growth curve and BrdU incorporation assay. Furthermore, knock down of endogenous GSDML 1 in HeLa cells could result in growth retardation, but such results could not been observed in HepG2 cells through several experimental models. We presume that the difference in the effect of GSDML1 may correlate with its subcellular localization. Study on the localization of GFP-GSDML1 in more cell lines showed that GFP-GSDML1 was localized mainly in the nucleus of MCF7, T47D, HeLa, Ishikawa, and CHO-K1 cell lines and in the cytoplasm of HepG2, N87, SW480, and U2OS cell lines (data not shown). The results also imply that GSDML may be involved in the progression of cancer in the female reproductive system. Although GSDML1 can stimulate proliferation of cells through nuclear localization, colony formation assay and tumorigenic assay on nude mice revealed that GSDML could not induce malignant transformation of cells, implying that GSDML may not be used as a proto-oncogene.

To investigate the molecular mechanism, we hypothesized that GSDML1 might interact with nuclear receptors because it contains two LXX(L/I)L motifs (amino acids 58–62 and 325–329) that have been found to be necessary and sufficient for interaction with the nuclear receptor [23,24]. Knock down of endogenous GSDML expression by siRNA led to the reduced activity of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and the sensitivity of ERα to estrogen ligand, suggesting that GSDML may be involved in the regulation of ERα activity in vivo (our unpublished data).

Taken together, we have cloned and characterized GSDML, a novel member of the GSDMDC family. The structure, tissue/cell expression profiling, and subcellular localization of GSDML were characterized. Our study revealed the role of GSDML in tumorigenesis of the uterine cervix cancer and its potential mechanism, contributing to the full understanding of the GSDMDC family. These results also provide the first evidence that GSDML can exert different effects on the basis of different subcellular localization, supplying new clues for elucidating the GSDMDC family's function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Lihui Wei for providing the Ishikawa cell lines and Wantao Chen for the ACC-2 and ACC-M cell lines.

Footnotes

This work was partially supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation Projects (30670406, 30621063), the Chinese State Key Programs in Basic Research (2007CB914601, 2006CB910802), and the Beijing Science and Technology NOVA Program (2007A063).

This article refers to supplementary materials, which are designated by Figures W1 and W2 and are available online at www.neoplasia.com.

References

- 1.Van Laer L, Huizing EH, Verstreken M, van Zuijlen D, Wauters JG, Bossuyt PJ, Van de Heyning P, McGuirt WT, Smith RJ, Willems PJ, et al. Nonsyndromic hearing impairment is associated with a mutation in DFNA5. Nat Genet. 1998;20:194–197. doi: 10.1038/2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katoh M, Katoh M. Identification and characterization of human DFNA5L, mouse Dfna5l, and rat Dfna5l genes in silico. Int J Oncol. 2004;25:765–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watabe K, Ito A, Asada H, Endo Y, Kobayashi T, Nakamoto K, Itami S, Takao S, Shinomura Y, Aikou T, et al. Structure, expression and chromosome mapping of MLZE, a novel gene which is preferentially expressed in metastatic melanoma cells. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:140–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saeki N, Kuwahara Y, Sasaki H, Satoh H, Shiroishi T. Gasdermin (Gsdm) localizing to mouse chromosome 11 is predominantly expressed in upper gastrointestinal tract but significantly suppressed in human gastric cancer cells. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:718–724. doi: 10.1007/s003350010138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katoh M, Katoh M. Evolutionary recombination hotspot around GSDML-GSDM locus is closely linked to the oncogenomic recombination hotspot around the PPP1R1B-ERBB2-GRB7 amplicon. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:757–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lage H, Helmbach H, Grottke C, Dietel M, Schadendorf D. DFNA5 (ICERE-1) contributes to acquired etoposide resistance in melanoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2001;494:54–59. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masuda Y, Futamura M, Kamino H, Nakamura Y, Kitamura N, Ohnishi S, Miyamoto Y, Ichikawa H, Ohta T, Ohki M, et al. The potential role of DFNA5, a hearing impairment gene, in p53-mediated cellular response to DNA damage. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:652–664. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akino K, Toyota M, Suzuki H, Imai T, Maruyama R, Kusano M, Nishikawa N, Watanabe Y, Sasaki Y, Abe T, et al. Identification of DFNA5 as a target of epigenetic inactivation in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamura M, Tanaka S, Fujii T, Aoki A, Komiyama H, Ezawa K, Sumiyama K, Sagai T, Shiroishi T. Members of a novel gene family, Gsdm, are expressed exclusively in the epithelium of the skin and gastrointestinal tract in a highly tissue-specific manner. Genomics. 2007;89:618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Deng B, Xing G, Teng Y, Tian C, Cheng X, Yin X, Yang J, Gao X, Zhu Y, et al. PACT is a negative regulator of p53 and essential for cell growth and embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7951–7956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701916104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang D, Chen W, Zhang Z, Zhang P, He R, Zhou X, Qiu W. Identification of genes with consistent expression alteration pattern in ACC-2 and ACC-M cells by cDNA array. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:448–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Xing G, Tie Y, Tang Y, Tian C, Li L, Sun L, Wei H, Zhu Y, He F. Role for the pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein CKIP-1 in AP-1 regulation and apoptosis. EMBO J. 2005;24:766–778. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Laer L, Pfister M, Thys S, Vrijens K, Mueller M, Umans L, Serneels L, Van Nassauw L, Kooy F, Smith RJ, et al. Mice lacking Dfna5 show a diverging number of cochlear fourth row outer hair cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:386–399. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunny DP, Weed E, Nolan PM, Marquardt A, Augustin M, Porter RM. Mutations in gasdermin 3 cause aberrant differentiation of the hair follicle and sebaceous gland. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:615–621. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maeda Y, Fukushima K, Kasai N, Maeta M, Nishizaki K. Quantification of TECTA and DFNA5 expression in the developing mouse cochlea. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3223–3226. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200110290-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busch-Nentwich E, Sollner C, Roehl H, Nicolson T. The deafness gene dfna5 is crucial for ugdh expression and HA production in the developing ear in zebrafish. Development. 2004;131:943–951. doi: 10.1242/dev.00961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delmaghani S, del Castillo FJ, Michel V, Leibovici M, Aghaie A, Ron U, Van Laer L, Ben-Tal N, Van Camp G, Weil D, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding pejvakin, a newly identified protein of the afferent auditory pathway, cause DFNB59 auditory neuropathy. Nat Genet. 2006;38:770–778. doi: 10.1038/ng1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwander M, Sczaniecka A, Grillet N, Bailey JS, Avenarius M, Najmabadi H, Steffy BM, Federe GC, Lagler EA, Banan R, et al. A forward genetics screen in mice identifies recessive deafness traits and reveals that pejvakin is essential for outer hair cell function. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2163–2175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4975-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sin HS, Huh JW, Kim DS, Kang DW, Min DS, Kim TH, Ha HS, Kim HH, Lee SY, Kim HS. Transcriptional control of the HERV-H LTR element of the GSDML gene in human tissues and cancer cells. Arch Virol. 2006;151:1985–1994. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lejeune F, Maquat LE. Mechanistic links between nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and pre-mRNA splicing in mammalian cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conti E, Izaurralde E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: molecular insights and mechanistic variations across species. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen ST, Hasegawa S, Tsuda H, Tomioka H, Ushijima M, Noda M, Omura K, Miki Y. Identification of a predictive gene expression signature of cervical lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:740–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. SRC-3/AIB1: transcriptional coactivator in oncogenesis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson-Rechavi M, Escriva Garcia H, Laudet V. The nuclear receptor superfamily. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:585–586. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.