Abstract

A strategy for cloning and mutagenesis of an infectious herpesvirus genome is described. The mouse cytomegalovirus genome was cloned and maintained as a 230 kb bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) in E. coli. Transfection of the BAC plasmid into eukaryotic cells led to a productive virus infection. The feasibility to introduce targeted mutations into the BAC cloned virus genome was shown by mutation of the immediate-early 1 gene and generation of a mutant virus. Thus, the complete construction of a mutant herpesvirus genome can now be carried out in a controlled manner prior to the reconstitution of infectious progeny. The described approach should be generally applicable to the mutagenesis of genomes of other large DNA viruses.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is an important human pathogen with a high prevalence in the human population that causes severe and even fatal disease in immunologically immature or immunocompromised patients (1). Because human and mouse CMV (MCMV) show a series of similarities in biology and pathogenesis (2) infection of the mouse with MCMV has become an extensively used in vivo model to study the pathogenesis of CMV infection. The 235-kb genomes of both human and mouse CMV are the largest genomes of mammalian DNA viruses. Sequence analysis of the human and mouse CMV genomes revealed a similar genetic organization and a coding capacity for presumably more than 220 polypeptides (3–5). However, information on the function of the majority of CMV gene products is still rather limited. This is in sharp contrast to the alphaherpesviruses, where the study of a wealth of viral mutants contributed significantly to the understanding of viral gene functions (reviewed in ref. 6). There is a lack of CMV mutants because due to the large genome size and slow replication kinetics construction of CMV recombinants turned out to be difficult.

The technique of insertional mutagenesis has been developed for disruption and deletion of CMV genes (7, 8). Because the frequency of homologous recombination in eukaryotic cells is low the technique is quite ineffective. In addition adventitious deletions and the formation of illegitimate recombinant viruses have frequently been observed (refs. 7 and 9; I.C., unpublished data). Although selection procedures have improved the original technique (9–11) generation of CMV mutants remains a laborious, time-consuming, and often unsuccessful task. Recently, the technique for construction of recombinant herpesviruses from cloned overlapping fragments (12) has been extended to CMV (13). This is a major improvement in that the technique generates only recombinant virus and obviates selection against nonrecombinant wild type (wt) virus. Still, the resultant mutant is the product of several recombination events in eukaryotic cells that are difficult to control. Correct reconstitution of the viral genome can only be verified after growth and isolation of the mutant virus.

Here we describe an approach for production of CMV mutants. Construction of the mutant genome is completely independent of the biological fitness of the mutant virus and the recombinant genome can be characterized and controlled prior to reconstitution of viral progeny. The MCMV genome was cloned as a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) in Escherichia coli and viral progeny were reconstituted by transfection of the MCMV BAC plasmid into eukaryotic cells that support virus production. The approach allows mutagenesis of the MCMV genome as one entity in E. coli using standard procedures, and the highly efficient generation of viral mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and Cells.

Propagation of MCMV (strain Smith, ATCC VR-194) in BALB/c mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (ATCC CRL1658) has been described (14, 15). Virus titers were determined in triplicate by plaque assay on MEF. Recombinant viruses were generated according to published protocols (8, 9, 15). To reconstitute virus progeny, BAC plasmids were transfected into MEF by the calcium phosphate precipitation technique essentially as described (20). Six hours posttransfection the MEF were treated with glycerol (15% glycerol in Hepes-buffered saline) for 3 min as described (20).

Isolation of Viral DNA and BAC Plasmids.

MCMV wt DNA was prepared from virions and total cell DNA was isolated from infected cells as described (14, 17). Circular virus DNA was isolated by the method of Hirt (18). Briefly, infected cells from a 60-mm tissue culture dish were lysed in 1 ml of buffer A (0.6% SDS/10 mM EDTA, pH 7.5), and 0.66 ml of 5 M NaCl were added. After incubation at 4°C for 24 h cellular DNA and proteins were precipitated by centrifugation at 15,000 × g and 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant was extracted with phenol/chloroform and DNA was precipitated with ethanol. The circular DNA was electroporated into electrocompetent E. coli DH10B as described (19). BAC plasmids were isolated from E. coli cultures using an alkaline lysis procedure (20) and further purified by precipitation with polyethylene glycol (20).

Plasmids and Mutagenesis.

For construction of recombination plasmids pRP2 and pRP3, a 17-kb HindIII-BamHI subfragment of the MCMV HindIII E′ fragment (17) was subcloned into pACYC177 (21). The EcoRI fragments O, b, f, and g within the HindIII E′ fragment (ref. 14; see Fig. 2) were deleted and an EcoRI-NotI adapter was added to create pHE′ΔE. The E. coli guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (gpt) (9) gene flanked by tandem loxP sites (22) was cloned into pKSO, a derivative of the BAC vector pBAC108L (19) with a modified polylinker (PmeI-NsiI-PacI-BamHI-PmeI-AscI). The pKSO-gpt plasmid was linearized with NotI between the two loxP sites and inserted in the NotI site of plasmid pHE′ΔE. pRP2 and pRP3 differ in the orientation of the pKSO-gpt sequences (see Fig. 2). To construct the mutagenesis plasmid pMieFS a 7.4-kb HpaI-EcoRI fragment (see Fig. 3a) from plasmid pIE111 (23) was inserted into pMBO96 (24) and the HindIII site in the insert was destroyed by treatment with Klenow polymerase. Mutagenesis of the MCMV BAC plasmid was performed by homologous recombination in the E. coli strain CBTS (25) following published protocols (24, 25).

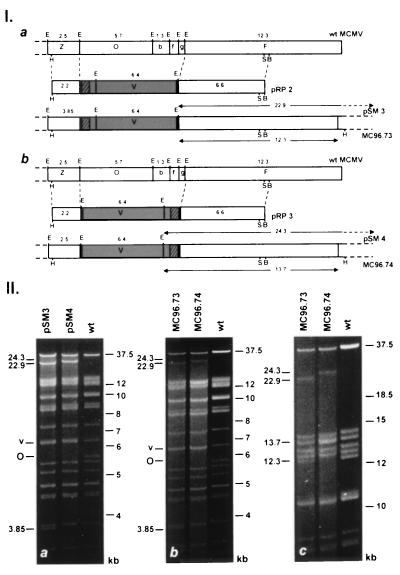

Figure 2.

Construction of MCMV BAC genomes and structural analysis of reconstituted virus genomes. (I) Recombinant BAC genomes were generated by homologous recombination in eukaryotic cells with the recombination plasmids pRP2 (a) and pRP3 (b). pRP2 and pRP3 contain 2.2 and 6.6 kb of flanking homologous sequences (open boxes), the BAC vector (shaded boxes) and the gpt gene (crosshatched boxes) flanked by loxP sites (solid box). The EcoRI restriction maps of the right-terminal end of the MCMV wt genome (Upper) and of the resulting BAC genomes pSM3 (a) and pSM4 (b) (Lower) are shown. New EcoRI fragments of 22.9 (a) and 24.3 kb (b) that result from the fusion of the termini in the BAC plasmids are indicated with arrows (above the genomes). Transfection of the BAC plasmids pSM3 and pSM4 into eukaryotic cells generated the recombinant viruses MC96.73 and MC96.74. The terminal EcoRI fragments of 12.3 (a) and 13.7 kb (b) in the linear genomes of these viruses are marked with arrows (below the genomes). Additional restriction enzyme sites indicated are BamHI (B), HindIII (H), and SfiI (S). (II) Structural analysis of BAC plasmids (a) and of reconstituted virus genomes (b, c). (a) Ethidium bromide stained agarose gel of EcoRI digested BAC plasmids pSM3 and pSM4 isolated from E. coli cultures and of MCMV wt DNA isolated from purified virions. (b) Restriction enzyme analysis of reconstituted virus genomes. DNA isolated from MC96.73 and MC96.74 infected cells and MCMV wt DNA was subjected to EcoRI digestion and separated by electrophoresis on 0.6% agarose gels for 14 h. The EcoRI O (O) and the vector fragments (v) are indicated and the size of additional bands is shown to the left. (c) Separation of the EcoRI fragments shown in b after electrophoresis for 28 h.

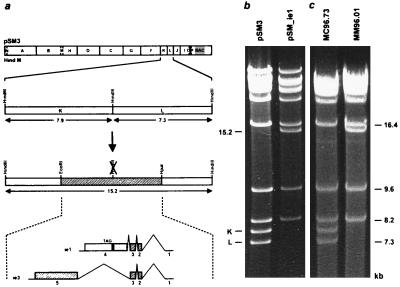

Figure 3.

Construction of ie1 mutant MM96.01 (a) and structural analysis of the mutated BAC plasmid (b) and of the ie1 mutant genome MM96.01 (c). (a) The HindIII site between the HindIII K and L fragments of the MCMV wt genome (Upper) was removed using the EcoRI-HpaI fragment (cross-hatched region) for mutagenesis. The exon-intron structure of the ie1 and ie3 genes is indicated below and protein coding sequences are depicted as cross-hatched boxes. The mutation resulted in a frame shift after 273 codons and created a new stop codon after additional nine codons (solid box). The open box denotes the part of the ie1 ORF, which is not translated in the mutant virus. (b) Ethidium bromide stained agarose gel of the HindIII digested parental BAC plasmid pSM3 and the mutated BAC plasmid pSM_ie1. (c) HindIII pattern of the genomes of recombinant virus MC96.73 and of ie1 mutant MM96.01. The HindIII K and L fragment and the new 15.2-kb fragment are indicated to the left and the size of some HindIII fragments is shown at the right margin.

RESULTS

Strategy for Cloning and Mutagenesis of the MCMV Genome.

The methods for manipulation of CMV genomes are limited in that they are based on homologous recombination in eukaryotic cells. To make the MCMV genome more accessible to mutagenesis, we decided to generate an infectious BAC of MCMV in E. coli. The strategy depicted in Fig. 1 was adopted for cloning of the MCMV genome because herpesviruses circularize their genome after cell entry (6, 26) and plasmid-like circular intermediates occur early in the herpesviral replication cycle (27). In the first step a recombinant virus was constructed by conventional methods that contained a bacterial vector integrated into its genome. After selection of recombinant virus using its selection marker gpt (9) circular intermediates should accumulate in infected cells. After isolation and electroporation of the circular intermediates into E. coli, the CMV BAC plasmid should be amenable to the powerful genetic techniques that were established for E. coli. Transfection of the mutated BAC plasmid into eukaryotic cells should eventually reconstitute viral mutants (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Strategy for cloning and mutagenesis of the MCMV genome. (A) Viral DNA and recombination plasmids containing the BAC were transfected into eukaryotic cells to generate a recombinant virus. Circular intermediates of the recombinant virus genome were isolated from infected cells and electroporated into E. coli. (B) Mutagenesis of the MCMV BAC plasmid was performed in E. coli by homologous recombination with a mutant allele (mut). (C) The mutated BAC plasmid was transfected into eukaryotic cells to reconstitute recombinant viruses.

Generation of Recombinant Viruses and BAC Plasmids.

We have shown previously (15) that a large region at the right-terminal end of the MCMV genome is not essential for replication in vitro. Therefore, this region was chosen for integration of the BAC vector and the selection marker gpt (Fig. 2 Ia and Ib). To analyze whether integration of the BAC vector into the viral genome could be achieved in both orientations, two different recombination plasmids, pRP2 and pRP3, were constructed (Fig. 2 Ia and Ib). For generation of BAC containing virus genomes the recombinant virus ΔMC95.21 was used that has a lacZ insertion in the EcoRI O fragment of its genome (I.C., unpublished report). This allowed the identification of integration events by screening for white plaques after staining with 5-bromo-3-chloro-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside. Recombinant viruses with integrated vector sequences were selected using the gpt marker and finally, circular virus DNA was isolated from infected cells and electroporated into E. coli.

A high percentage of bacterial clones (≈80%) contained the expected full-length plasmids. In comparison to DNA isolated from MCMV virions, BAC plasmids pSM3 and pSM4 contained additional EcoRI fragments of 22.9 and 24.3 kb, respectively (Fig. 2IIa), depending on the orientation of the integrated vector (Fig. 2Ia and Ib). The additional bands resulted from the fusion of the terminal EcoRI fragments indicating the circular nature of the BAC plasmids (Fig. 2 Ia and Ib). As expected the 5.7-kb EcoRI O fragment was missing in the BAC plasmids (see Fig. 2 Ia, Ib, IIa) and the vector sequences resulted in a double band at 6.4 kb (labeled v in Fig. 2IIa). In the BAC plasmid pSM3 the 2.5-kb EcoRI Z fragment was enlarged by 1.4 kb of gpt and vector sequences leading to a 3.85-kb fragment (Fig. 2 Ia and IIa, lane pSM3). Southern blot analysis and characterization of the BAC plasmids with restriction enzymes HindIII, XbaI, and BamHI (data not shown) confirmed the successful cloning of the complete genome of these MCMV recombinants into E. coli.

Reconstitution of Virus Progeny from MCMV BAC Plasmids.

Transfection of BAC plasmids pSM3 and pSM4 into MEF led to the development of plaques. New cell monolayers were infected with supernatant derived from pSM3 and pSM4 transfected cells, and total cell DNA was isolated when cells showed a complete cytopathic effect. EcoRI digestion of the isolated DNA resulted in a similar pattern as digestion of the BAC plasmids pSM3 and pSM4 (compare lanes MC96.73 and MC96.74 in Fig. 2IIb and lanes pSM3 and pSM4 in Fig. 2IIa). DNA isolated from infected cells comprises circular, concatemeric and linear viral DNA, which is already packaged into capsids. Therefore, the amount of the 22.9- and 24.3-kb fragments resulting from the fusion of the terminal EcoRI fragments was submolar (Fig. 2IIb, lanes MC96.73 and MC96.74). Furthermore, terminal EcoRI fragments originating from linear genomes reappeared. The terminal EcoRI fragment F (12.3 kb) was seen in the genomes of the recombinant MC96.73 as in wt MCMV (Fig. 2IIc, lanes MC96.73 and wt). In the recombinant MC96.74 the terminal EcoRI fragment F was enlarged by 1.4 kb of vector sequences (see Fig. 2Ib), resulting in a double band at 13.7 kb (Fig. 2IIc, lane MC96.74). Digestion with restriction enzymes BamHI and XbaI revealed all expected bands (data not shown). Thus, we were able to reconstitute CMV recombinants from one large plasmid without any manipulation prior to transfection.

Construction of a MCMV ie1 Mutant by Homologous Recombination in E. coli.

To test the efficacy of targeted mutagenesis in E. coli, a small mutation was introduced in the immediate-early (ie) region of the MCMV genome. At least two alternatively spliced transcripts arise from the ie region (Fig. 3a) that encode the ie1 protein pp89 and the 88 kDa ie3 protein (16). Due to the complex structure of the ie1/ie3 transcription unit disruption of the ie1 gene is probably difficult to achieve by conventional recombination techniques without affecting the expression of the ie3 gene. Therefore it was not known whether the MCMV ie1 protein is essential for virus replication. To disrupt the ie1 ORF (595 codons) a frame shift mutation was introduced at a HindIII site in exon 4 of the ie1 gene. The mutation truncated the authentic reading frame after codon 273 and created a new stop codon after additional nine codons (Fig. 3a). The mutation was constructed on a 7.4-kb EcoRI-HpaI fragment (Fig. 3a) and subsequently transferred to the BAC plasmid pSM3 by homologous recombination in E. coli employing a two-step replacement strategy (24, 25). The mutagenesis procedure resulted in the loss of the HindIII K and L fragments and the generation of a new 15.2-kb fragment (Fig. 3b). The EcoRI and BamHI patterns of the BAC plasmids were unchanged (data not shown) confirming that the BAC plasmids remained stable during the mutagenesis procedure. Transfection of the mutated BAC plasmid pSM_ie1 into MEF led to plaque formation. Total cell DNA was isolated from infected cells and analyzed by HindIII digestion. As expected, the HindIII K and L fragments were replaced by the 15.2-kb fragment in the genome of the ie1 mutant virus MM96.01 (Fig. 3c). Hence, the mutation introduced in the MCMV BAC plasmid was maintained after reconstitution of the mutant virus.

Characterization of the ie1 Mutant.

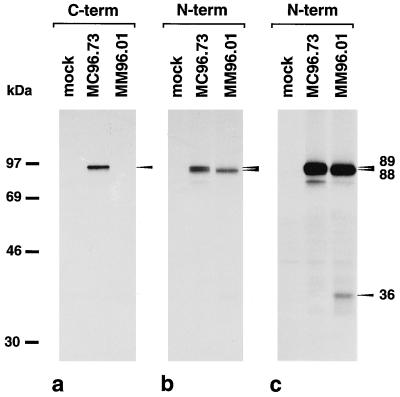

Absence of the ie1 protein in MM96.01 infected cells was confirmed by immunoprecipitation. An antiserum directed to the C terminus of pp89 (16) detected the ie1 protein in lysates of MC96.73 infected cells but did not precipitate any protein from lysates of MM96.01 infected cells (Fig. 4a). An ie1/ie3 specific antiserum directed against N-terminal sequences (16, 28) detected two proteins of 89 and 88 kDa in lysates of MC96.73 and one protein of 88 kDa in lysates of MM96.01 infected cells (Fig. 4b). In the MM96.01 lane the 89-kDa ie1 protein was clearly missing and only the 88-kDa ie3 protein was seen (Fig. 4b). A longer exposure of the autoradiograph revealed a 36-kDa protein in MM96.01 infected cells (Fig. 4c). The apparent molecular weight of this polypeptide is in agreement with the expected molecular mass for the truncated ie1 protein and with the migration behavior of various ie1 mutant proteins (28).

Figure 4.

Absence of the ie1 protein pp89 in cells infected with ie1 mutant MM96.01. MEF were either mock-infected, infected with recombinant virus MC96.73 or ie1 mutant MM96.01 in the presence of cycloheximide (50 μg/ml) for 3 h to achieve the selective expression of ie genes (16). After removal of cycloheximide, actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) was added and proteins were labeled with [35S]-methionine (1,200 Ci/mmol) for an additional 3 h. Lysis of cells and immunoprecipitations were performed as described (28) using an antiserum directed to the C terminus of the ie1 protein (a) and an ie1/ie3-specific antipeptide serum (b) directed against N-terminal sequences (16, 28). A long exposure of the autoradiograph in b is shown in c.

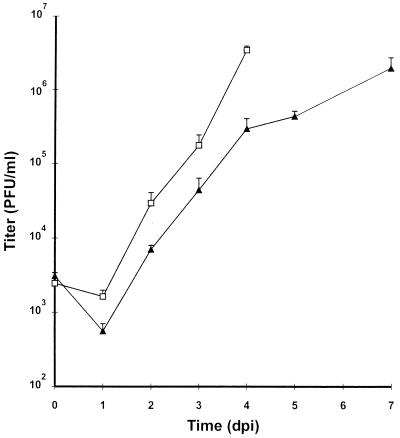

After transfection of the BAC plasmid pSM_ie1 into MEF it was already observed that the reconstituted ie1 mutant formed smaller plaques than the parental virus and that the infection spread slowly. To determine the growth kinetics of the mutant virus MM96.01 MEF were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 1. The ie1 mutant showed a significantly slower growth than the parental virus (Fig. 5) but with a delay of ≈3 days titers comparable to wt virus (>106 PFU/ml) were achieved in the supernatant of MM96.01 infected cells. We concluded therefore that the ie1 protein pp89 is not essential for replication in vitro, however, it improves the growth of MCMV significantly.

Figure 5.

Growth of the ie1 mutant MM96.01 and the parental virus MC96.73. MEF were infected with MM96.01 (▴) or MC96.73 (□) at a multiplicity of infection of 1. Supernatants of the infected cells were harvested at the indicated time points and titers of progeny were determined by plaque assay.

DISCUSSION

In this communication, we report a novel strategy for the genetic manipulation of large viral DNA genomes. In a single step we cloned an infectious cytomegalovirus DNA as a bacterial artificial chromosome in E. coli and reconstituted virus progeny after transfection of the BAC plasmid into eukaryotic cells. This approach makes the CMV genome accessible to the genetic techniques established for E. coli. As an example for the power of the mutagenesis procedures, we performed a targeted insertion of four nucleotides into the 230-kb MCMV genome. In principle, any mutation (point mutations, insertions, and deletions) in any region of the genome can now be introduced using the described mutagenesis procedure. Moreover, other procedures, for example a random transposon mutagenesis of the CMV genome are conceivable. Multiple mutations can be introduced in consecutive rounds of mutagenesis without the need to reconstitute infectious viral intermediates. Construction of revertant genomes can be easily accomplished by an additional round of mutagenesis in E. coli. Characterization of the mutated genome prior to reconstitution of the recombinant virus is a major advantage of the new method because adventitious deletions and illegitimate insertions frequently encountered with conventional recombination techniques are often detectable only after lengthy selection rounds. Generation of virus mutants with growth disadvantages will probably be facilitated because construction of the mutant genome is completely independent of the biological properties of the mutant virus. In summary, the new method will facilitate the genetic analysis of CMV functions and might be useful for construction of viral vectors.

Reconstitution of recombinant CMV genomes from overlapping fragments cloned in cosmids has recently been described for human CMV (13, 29). This method also leads directly to the generation of recombinant viruses and circumvents the selection against wt viruses. However, the subgenomic fragments have to be released from the vector backbone prior to transfection and several recombination events are required in eukaryotic cells for reconstitution (13). Once established, reconstitution of recombinants from supercoiled BAC plasmids is probably more efficient and reliable than reconstitution from overlapping fragments.

Cloning of an infectious viral genome as a yeast artificial chromosome and genetic manipulation in yeast has been described for adenovirus (30). This might be an alternative to the described strategy although it remains to be shown whether large herpesvirus genomes can be cloned as yeast artificial chromosomes and whether the genomes are stable in yeast. BACs were developed with the intention to maintain large DNA fragments stably in E. coli, and the low and stringently controlled copy number of such vectors has made them superior to cosmid and yeast artificial chromosome vectors (19, 31). We have propagated bacteria containing herpesviral genomes as BAC plasmids for weeks and found the restriction pattern of the plasmids unchanged (data not shown). Most importantly, we were able to reconstitute virus progeny from the propagated BAC plasmids. It therefore appears that large DNA inserts remain stable in F factor replicons under appropriate selection and culture conditions.

For construction of the MCMV BAC plasmid a nonessential region of the genome was replaced by vector sequences. The insertion remained stable in the genome of the reconstituted viruses. Because the deleted genes are nonessential for replication in vitro, the insertion does not interfere with analyses performed with recombinant viruses in vitro. Nevertheless, it is desirable to reconstitute the complete wt genome and to have the opportunity to excise the vector sequences. Since there is no size constraint for the BAC plasmid in E. coli the MCMV wt genome can now be reconstituted by homologous recombination in E. coli. By flanking the vector sequence with loxP sites the possibility to excise the vector with recombinase cre (22) was created.

Recently, a human CMV ie1 mutant has been constructed that exhibited a slow replication kinetics and failed to replicate in human fibroblasts at low multiplicity of infection (29). The growth kinetics of the MCMV ie1 mutant is very reminiscent to that of the human CMV ie1 mutant, however the MCMV ie1 mutant was generated in MEF and there was no need to grow the mutant in an ie1 complementing cell line. Positive autoregulation of the major immediate-early promoter and augmentation of early promoter transactivation has been described for the MCMV and the human CMV ie1 proteins (16, 29, 32–34). Additional experiments are required to analyze the expression kinetics of the viral gene classes in MM96.01 infected cells and to determine whether autoregulation and/or early transactivation are impaired. It cannot be ruled out that some activity remained in the truncated ie1 protein. This might explain the growth of the MCMV ie1 mutant in noncomplementing cells, whereas the human CMV ie1 deletion mutant cannot replicate in fibroblasts at low multiplicity of infection.

In principle, the strategy for cloning of the MCMV genome is applicable to all DNA viruses that produce circular intermediates during genome replication. Insertion of the BAC vector requires only limited sequence information of the viral genome. Therefore, the technique may facilitate cloning of incompletely characterized virus genomes. Alternatively, viral genomes can be inserted into the BAC vector by conventional cloning techniques or complete genomes can be reconstituted from subgenomic fragments by the chromosomal building technique (24, 25). Maintenance and manipulation of large viral genomes in E. coli will be especially interesting for those viruses that are difficult to grow in cell culture systems and that are cumbersome to manipulate and to analyze.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Simon and D. Spector for providing plasmids pBAC108L and HindIII E′, respectively, and S. Eichler and S. Gier for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by Grant 174/95 to M.M. from the Medical Faculty of the University of Heidelberg and by Grant BMBF 01GE96140 to M.M and U.H.K. from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: BAC, bacterial artificial chromosome; CMV, cytomegalovirus; gpt, guanine phosphoribosyl transferase; ie, immediate-early; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; MCMV, mouse cytomegalovirus; wt, wild type.

References

- 1.Britt W J, Alford C A. In: Fields Virology. Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. New York: Lippincott–Raven; 1996. pp. 2493–2523. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho M, editor. Cytomegalovirus: Biology and Infection. New York: Plenum; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chee M S, Bankier A T, Beck S, Bohni R, Brown C M, Cerny R, Horsnell T, Hutchison C A, Kouzarides T, Martignetti J A, Preddie E, Satchwell S C, Tomlinson P, Weston K M, Barrell B G. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;154:125–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74980-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cha T-A, Tom E, Kemble G W, Duke G M, Mocarski E S, Spaete R R. J Virol. 1996;70:78–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.78-83.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rawlinson W D, Farrell H E, Barrell B G. J Virol. 1996;70:8833–8849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8833-8849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roizman B, Sears A E. In: Fields Virology. Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. New York: Lippincott–Raven; 1996. pp. 2231–2295. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spaete R, Mocarski E S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7213–7217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manning W C, Mocarski E S. Virology. 1988;167:477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vieira J, Farrell H E, Rawlinson W D, Mocarski E S. J Virol. 1994;68:4837–4846. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4837-4846.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff D, Jahn G, Plachter B. Gene. 1993;130:167–173. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90416-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greaves R F, Brown J M, Vieira J, Mocarski E S. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2151–2160. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Zijl M, Quint W, Briaire J, de Rover T, Gielkens A, Berns A. J Virol. 1988;62:2191–2195. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2191-2195.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemble G, Duke G, Winter R, Spaete R. J Virol. 1996;70:2044–2048. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.2044-2048.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebeling A, Keil G M, Knust E, Koszinowski U H. J Virol. 1983;47:421–433. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.3.421-433.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thäle R, Szepan U, Hengel H, Geginat G, Lucin P, Koszinowski U H. J Virol. 1995;69:6098–6105. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6098-6105.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messerle M, Bühler B, Keil G M, Koszinowski U H. J Virol. 1992;66:27–36. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.27-36.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercer J A, Marks J R, Spector D H. Virology. 1983;129:94–106. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirt B. J Mol Biol. 1967;26:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shizuya H, Birren B, Kim U-J, Mancino V, Slepak T, Tachiiri Y, Simon M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8794–8797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang A C, Cohen S N. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sauer B. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:890–900. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keil G M, Ebeling-Keil A, Koszinowski U H. J Virol. 1987;56:526–533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.2.526-533.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connor M, Peifer M, Bender W. Science. 1989;244:1307–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.2660262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempkes B, Pich D, Zeidler R, Sugden B, Hammerschmidt W. J Virol. 1995;69:231–238. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.231-238.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mocarski E S. In: Fields Virology. Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. New York: Lippincott–Raven; 1996. pp. 2447–2492. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfüller R, Hammerschmidt W. J Virol. 1996;70:3423–3431. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3423-3431.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Del Val M, Volkmer H, Rothbard J B, Jonjic S, Messerle M, Schickedanz J, Reddehase M J, Koszinowski U H. J Virol. 1988;62:3965–3972. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.3965-3972.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mocarski E S, Kemble G W, Lyle J M, Greaves R F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11321–11326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ketner G, Spencer F, Tugendreich S, Connely C, Hieter P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6180–6190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim U-J, Shizuya H, deJong P J, Birren B, Simon M I. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1083–1085. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.5.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambucetti L C, Cherrington J M, Wilkinson G W G, Mocarski E S. EMBO J. 1989;8:4251–4258. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malone C L, Vesole D H, Stinski M F. J Virol. 1990;64:1498–1506. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1498-1506.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenberg R M, Fortney J, Barlow S W, Magrane B P, Nelson J A, Ghazal P. J Virol. 1990;64:1556–1565. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1556-1565.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]