Abstract

Warfarin dosing is correlated with polymorphisms in vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1 (VKORC1) and the cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9) genes. Recently, the FDA revised warfarin labeling to raise physician awareness about these genetic effects. Randomized clinical trials are underway to test genetically based dosing algorithms. It is thus important to determine whether common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in other gene(s) have a large effect on warfarin dosing. A retrospective genome-wide association study was designed to identify polymorphisms that could explain a large fraction of the dose variance. White patients from an index warfarin population (n = 181) and 2 independent replication patient populations (n = 374) were studied. From the approximately 550 000 polymorphisms tested, the most significant independent effect was associated with VKORC1 polymorphisms (P = 6.2 × 10−13) in the index patients. CYP2C9 (rs1057910 CYP2C9*3) and rs4917639) was associated with dose at moderate significance levels (P ∼ 10−4). Replication polymorphisms (355 SNPs) from the index study did not show any significant effects in the replication patient sets. We conclude that common SNPs with large effects on warfarin dose are unlikely to be discovered outside of the CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes. Randomized clinical trials that account for these 2 genes should therefore produce results that are definitive and broadly applicable.

Introduction

The determination of safe yet effective doses of warfarin for individual patients is one of the most promising clinical applications of pharmacogenetics.1–3 There are large variation in warfarin dose from patient to patient and significant clinical consequences of doses that produce insufficient or excessive pharmacologic effects. Thus, reducing uncertainty in establishing the therapeutic dose in individual patients could improve quality of care as well as expand the range of patients who could be treated.4

In white patients, genetic factors are more strongly correlated with stabilized warfarin dose than all other known patient-related factors. Warfarin pharmacokinetics are affected by functional polymorphisms (*2, Arg144Cys; *3, Ile359Leu) in cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9).5,6 In addition, warfarin's effects are modulated by polymorphisms (eg, −1639, rs9923231) in the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1 (VKORC1) enzyme, a critical component of the vitamin K cycle discovered in part because of its contribution to bleeding disorders and warfarin resistance.7,8 Both VKORC1 and CYP2C9 polymorphisms independently correlate with warfarin dose9,10 and other clinical outcomes such as time to stabilized dose, bleeding events, and time within the target therapeutic range.11–13 Combined polymorphisms in VKORC1 and CYP2C9 explain approximately 30% (20%-25% for VKORC1; 5%-10% for CYP2C9) of the variance in the stabilized warfarin dose distribution.10,14,15 The importance of these strong genetic effects was recognized by recent relabeling of warfarin by the FDA to raise awareness in the clinical community.16 However, it is important to note that patient demographics, clinical factors, and genetic variants combined explain only 45% to 55% of the total dose variance.2,3

Both VKORC1 and CYP2C9 were identified to be important as a result of their functional relationship to warfarin pharmacology. Other warfarin candidate genes that are part of the vitamin K pathway, vitamin K–dependent clotting factors, or minor metabolic or transport pathways have been systematically screened, with only VKORC1 and CYP2C9 reaching significance.17 Generally, dose associations with other candidate genes have shown small statistical effects or fail to replicate in independent populations.15,18,19 It remains unclear whether additional common genetic variation outside of these candidate genes contribute significantly to the 45% to 55% of unexplained variance in warfarin dosing.

The utility of prospective, pharmacogenetically guided warfarin dosing has been studied in a small patient set,20 but a proposed large National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI)–funded randomized clinical trial should provide more definitive data addressing this (Request for Proposal NHLBI-HV-08-03). Although polymorphisms with small effect on warfarin dose would probably not be incorporated into this trial, knowledge of additional polymorphisms with a large effect would be extremely valuable. Indeed, if polymorphisms with large effects are neglected in upcoming clinical trials, the interpretation of the results from these studies would be significantly compromised, necessitating costly reexamination of samples and/or additional trials. With this in mind, we set out to identify additional common genetic variation that may be strongly predictive of stabilized warfarin dose using a genome-wide association study (GWAS) design.

Methods

Study setting and design

The University of Washington Medical Center index patient sample consisted of a cohort used previously to assess the association between CYP2C9 variants and anticoagulation-related outcomes12 and the effects of VKORC1, CYP2C9, and GGCX polymorphisms on warfarin maintenance dose.10,18 Recruitment of these patients used the following inclusion criteria: (1) patients with a confirmed index date of first warfarin exposure, (2) patients currently undergoing anticoagulation therapy, and (3) patients older than 18 years. Data collection for the primary patient cohort consisted of a review of inpatient and outpatient medical records. The University of Washington Medical Center anticoagulation database was used to obtain information on International Normalized Ratio (INR) measurements, warfarin daily dose, prescription drugs, and demographic variables. The primary outcome analyzed for this study was daily maintenance warfarin dose, which was defined as 3 consecutive clinic visits having INR measurements within therapeutic range at the same mean daily dose. This study used 184 white patients whose DNA was available for whole genome genotyping, and after quality control 181 patients were analyzed. This study was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee at the University of Washington and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Replication populations were derived from 2 different patient sets. A total of 287 white patients were drawn from several clinics coordinated through the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Florida. This patient set has previously been studied for the effects of VKORC1 and other candidate genes on stabilized warfarin dosing.19 Stable warfarin dose was defined by less than 10% variability between clinic visits and an INR within the target range at more than 3 visits. Exclusion criteria for these patients were liver cirrhosis, advanced malignancy, hospitalization within 4 weeks before the index visit, or febrile/diarrheal illness within 2 weeks of the index visit. The presence or absence of exclusion criteria was ascertained from a brief patient interview and chart review, both of which were conducted by trained study personnel using a standardized questionnaire to abstract the pertinent data. The University of Florida Institutional Review Board approved this study.

The second replication set was obtained from Vanderbilt University (n = 92 white patients). These patients were treated at 3 anticoagulation clinics affiliated with the Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Patients presenting for initiation of warfarin therapy were prospectively screened to determine eligibility for the study and enrolled if written informed consent was obtained. The Vanderbilt samples were collected to evaluate the effects of VKORC1 and CYP2C9 during initiation of warfarin therapy.21 For this study, stable warfarin dose is defined as the average weekly dose (irrespective of achieved INR) that the patient received during the observation period, excluding the first 28 days after warfarin initiation. Exclusion criteria were active alcoholism and a diagnosis of active cancer requiring, or with the potential to require, concurrent chemotherapy. The Human Subjects Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University approved this study.

Given the minor differences in stable dose definition, geographic origin of patients, and other potentially important differences among the 3 sample populations, we examined whether there may be systematic differences in the dose response phenotype that may obscure or falsely support genetic correlations comparing these different patient sets. We compared the 3 dose distributions and found no significant differences (P > .15 in all comparisons) among them by both parametric and nonparametric tests (ie, analysis of variance, pairwise t tests, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov; data not shown). We focused solely on patients who self-identified as being of European ancestry to limit the potential influence of population stratification.

Genotyping

In the index patient population, DNA samples were drawn from either whole blood genomic DNA (n = 124) or whole genome amplified (WGA) DNA (REPLI-g, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) (n = 57). Each sample was genotyped using the Illumina (San Diego, CA) HumanHap 550K, version 3 BeadChip, which assays 561 278 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs). Current estimates suggest that the 550K BeadChip provides 90% coverage (r2 = 0.80) of common (minor allele frequency ≥ 0.05) SNP variation present in the European HapMap population.22,23 The average number of SNPs producing a genotype (ie, call rate) was 98.8% (99.4% extracted, 97.8% WGA). We eliminated SNPs whose minor allele was observed in fewer than 4 samples (<1.3% allele frequency; 22 649 SNPs) because the power to detect an association for these SNPs is expected to be prohibitively low. We also identified and eliminated 1 sample with a poor genotyping call rate (78%) from further analysis.

For quality control, we performed gender checks using a Taqman genotyping assay.24 We also compared the genotypes generated in our genome-wide analysis to SNP genotypes previously generated for the same samples by targeted resequencing at 8 SNPs in 4 different genes: CYP2C9*3 (rs1057910), VKORC1 (rs7294), CALU (rs2290228, rs1057910, rs109829, rs1043550, rs1043595), and GGCX (rs2028898). These comparisons identified 2 samples that could not be unambiguously identified and were excluded from further analysis. For the remaining samples, the average concordance was more than 99% across all 8 SNPs (2668 genotypes), with each site more than 98% in agreement and 2 sites 100% in agreement. In total, 181 samples from the University of Washington were analyzed at 538 629 SNPs.

Replication genotyping

We genotyped a total of 379 independently collected, replication patient samples (n = 287, University of Florida; n = 92, Vanderbilt) for 384 SNPs using the Illumina BeadExpress genotyping technology. The replication panel was genotyped for loci associated with warfarin dose in the index population (“Statistical analysis”) at a P value of less than 10−4, integrating information from both our univariate and multivariate additive models, as well as models to identify dominant/recessive and interacting effects (“Statistical analysis”). Furthermore, we included SNPs that had P values less than 10−3 if they were within 500 kb of one of 30 candidate genes that had been previously proposed to be important to warfarin metabolism and/or mode of action.17 After scoring for assay suitability, some replication SNPs could not be genotyped in this assay. Twenty-nine SNP assays of 384 failed to yield high-quality genotypes, leaving 355 to be analyzed in the replication samples. A limited number of SNPs, including a failure in the BeadExpress assay, were genotyped using Taqman assays only on the 287 samples from the University of Florida (eg, rs11865472, Table 1).

Table 1.

Top replication polymorphisms associated with stabilized warfarin dose

| rsID | Genome coordinate* | Index P (UW) | Replication P (UF and Vanderbilt) | Combined P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs9923231† | chr16:31015190 | 6.2 × 10−13 | 1.0 × 10−22 | 4.7 × 10−34 |

| rs4086116‡ | chr10:96697192 | 8.3 × 10−5 | 1.2 × 10−8 | 6.2 × 10−12 |

| rs2286461 | chr4:15572771 | 6.6 × 10−7 | 6.7 × 10−2 | 1.8 × 10−5 |

| rs10920212 | chr1:199713096 | 1.1 × 10−5 | 3.3 × 10−1 | 4.8 × 10−2 |

| rs549427 | chr11:113590069 | 1.4 × 10−5 | 7.0 × 10−1 | 2.1 × 10−3 |

| rs719473 | chr15:88799068 | 1.6 × 10−5 | 5.0 × 10−1 | 3.6 × 10−2 |

| rs11865472 | chr16:1124968 | 1.7 × 10−5 | 2.6 × 10−1§ | NA |

| rs10503266 | chr8:4475454 | 2.0 × 10−5 | 6.8 × 10−1 | 2.2 × 10−2 |

| rs1543245 | chr15:35144802 | 2.4 × 10−5 | 9.4 × 10−1 | 10.0 × 10−3 |

| rs2022212 | chr6:69588678 | 2.6 × 10−5 | 3.7 × 10−1 | 4.9 × 10−2 |

| rs3858304 | chr10:132039565 | 3.2 × 10−5 | 2.2 × 10−1 | 6.7 × 10−4 |

| rs11728293 | chr4:35677976 | 3.3 × 10−5 | 6.2 × 10−1 | 2.8 × 10−3 |

| rs16894959 | chr6:34933640 | 4.0 × 10−5 | 2.9 × 10−1 | 3.5 × 10−3 |

| rs17784218 | chr10:50435360 | 4.2 × 10−5 | 4.2 × 10−2 | 9.4 × 10−1 |

| rs10489371 | chr1:167199124 | 4.4 × 10−5 | 5.7 × 10−1 | 6.6 × 10−2 |

| rs2589949 | chr15:88756019 | 4.5 × 10−5 | 8.9 × 10−1 | 7.8 × 10−3 |

| rs1635852 | chr7:28155936 | 4.5 × 10−5 | 7.0 × 10−1 | 5.1 × 10−3 |

| rs3000802 | chr1:225675527 | 4.7 × 10−5 | 9.0 × 10−1 | 1.3 × 10−2 |

| rs12665384 | chr6:69747288 | 5.2 × 10−5 | 8.0 × 10−1 | 4.7 × 10−3 |

| rs10117842 | chr9:72631257 | 5.4 × 10−5 | 7.2 × 10−1 | 5.0 × 10−3 |

| rs2189784 | chr19:15820200 | 5.4 × 10−5 | 4.9 × 10−1 | 3.5 × 10−3 |

| rs11733360 | chr4:7478732 | 5.6 × 10−5 | 2.9 × 10−1 | 1.2 × 10−3 |

| rs2814944 | chr6:34660775 | 6.2 × 10−5 | 3.9 × 10−1 | 6.6 × 10−3 |

| rs2859720 | chr20:4602585 | 6.6 × 10−5 | 4.4 × 10−4 | 7.1 × 10−1 |

| rs1572237 | chr10:129202681 | 7.3 × 10−5 | 6.1 × 10−1 | 2.5 × 10−2 |

| rs913068 | chr20:55117490 | 7.4 × 10−5 | 3.6 × 10−1 | 2.1 × 10−3 |

| rs16991615 | chr20:5896227 | 7.5 × 10−5 | 6.3 × 10−1 | 5.6 × 10−1 |

All P values are generated from univariate analysis assuming an additive genetic model.

NA indicates not applicable; UW, University of Washington; and UF, University of Florida.

Coordinate for hg18; genome.ucsc.edu.

rs9923231 (also known as VKORC1 −1639) genotypes had been previously generated for all three populations and is perfectly correlated with rs10871454 (see Table 2).

Best replicated SNP in CYP2C9 and in perfect linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 1.0; CEU HapMap) with rs4917639.

Data available from only the University of Florida (UF; see “Replication genotyping”).

Quality control for the replication genotypes consisted of gender and genotype concordance at previously assayed SNPs. From the genotype data collected by Vanderbilt University, 5 of the 92 samples could not be reliably identified because of gender discrepancies and/or multiple genotyping discordances. These 5 samples were excluded from further analysis. Of the remaining 87 samples, a concordance rate of more than 99% was observed from 4 previously genotyped SNPs. We also found more than 99% concordance for 2 replication SNPs independently assayed by the University of Florida. Of the 287 samples from this site, none failed our quality control criteria.

Statistical analysis

To identify SNPs that may be associated with stabilized warfarin dose, we performed linear regression on log-transformed warfarin dose, measured in milligrams per day, against genotype at each of the SNP sites. For our primary analysis, we used an additive effects model in which the mean dose for heterozygotes is assumed to be intermediate to either homozygous genotype. We conducted our analyses in 2 contexts: univariate considered SNP effect only, and multivariate considered SNP effect and patient/clinical covariates including age, gender, treatment with amiodarone, treatment with losartan, CYP2C9 genotype (coded as a binary variable differentiating carriers of either *2 or *3 alleles), and VKORC1 genotype, coded as an additive effect variable for genotype at the −1639 position (rs9923231).10 In other exploratory analyses, we considered dominant/recessive models in both possible orientations (major allele dominant/minor allele dominant), and 2 interaction models testing for epistasis for each genotyped SNP with the genotype at VKORC1 or CYP2C9. The primary results reported here are from the univariate additive models (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), although our replication genotype panel included the top-ranking SNPs based on P values from these other models.

We established a P value of 10−7 as a cutoff for a significant association (roughly equivalent to a Bonferroni adjusted P value of .05 assuming ∼550 000 tests) in the index population. However, we attempted to replicate all sites of variation that produced a P value less than 10−4 in the index population; we included a polymorphism if it achieved this level of significance in any of the effect models tested (univariate, multivariate, additive, dominant/recessive, and interaction). We also attempted to replicate any variant within 500 kb of a previously defined candidate gene17 if it achieved a P value of less than 10−3 in any tested model. For the replication analysis, a P value of 10−4 (roughly equivalent to a Bonferroni-adjusted [355 tests] P value of .05) was established as a cutoff for confirmation in the replication population.

To extend our GWAS results to a larger set of common polymorphisms from the entire HapMap set (∼3.1 million), we used imputation methods to infer genotypes and subsequently identify warfarin dose associations.25 These imputation association methods use Bayesian approaches to quantify genotype-phenotype association (ie, Bayes factor). In addition, we implemented the imputation methods using resequencing data from both the Seattle SNPs (n = 303 genes; pga.gs.washington.edu) and the Environmental Genome Project (n = 613 genes).26,27 These resequencing efforts focused on candidate genes from inflammatory, clotting, vitamin K, and environmental response pathways (http://gvs.gs.washington.edu/GVS/).

Results

Regression results

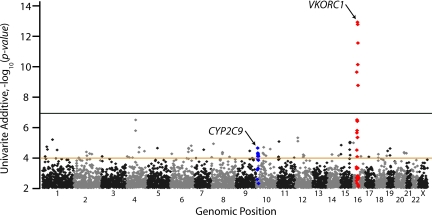

Of 538 629 SNPs tested in univariate linear regression, VKORC1 has the single most important genetic influence on stabilized warfarin dose in the index population (Figure 1; Table 2), with the most significant SNP (rs10871454; P = 6.2 × 10−13) located 60 kb 5′ of VKORC1 (Table 2). This association explains approximately 25% of the variance in log-transformed stabilized dose, and this SNP is in perfect linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 1.0) with other VKORC1 SNPs (eg, −1639; rs9923231) in the HapMap CEPH European samples. No other tested SNPs achieved nominal genome-wide significance (P < 10−7) in the index population, other than those in linkage disequilibrium with the surrogate VKORC1 SNP (rs10871454). SNPs near CYP2C9 were more modestly associated with warfarin dose, with a number of correlated variants less than or equal to 10−4. For example, rs4917639, which has been shown previously to effectively tag both the *2 and *3 nonsynonymous variants,17 had a P value of 9.7 × 10−5. Polymorphisms within 100 kb of 30 well-studied candidate genes did not show any association when examining the lowest univariate P values in the region (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Genome-wide P values for warfarin dose association in the index population. All P values shown are for univariate effects using an additive genetic model. Chromosomes are numbered on the x-axis. Polymorphisms within 500 kb of VKORC1 and CYP2C9 are shown in red and blue, respectively. Genome-wide significance was set at the P value 10−7 (black line), and polymorphisms with P values less than 10−4 (brown line) were selected for replication, among others (see “Statistical analysis”).

Table 2.

Best associations in warfarin-related candidate genes in the index patient population (University of Washington)

| Gene symbol/cluster* | Genome coordinate† | RsID | P‡ | Total SNPs in region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VKORC1 | chr16:30955580 | rs10871454§ | 6.2 × 10−13 | 10 |

| CYP2C9(*2/*3 tag) | chr10:96715525 | rs4917639 | 9.7 × 10−5 | 1 |

| CYP2C9(*3) | chr10:96731043 | rs1057910 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 1 |

| CYP2C18/CYP2C19/CYP2C8/CYP2C9 | chr10:96454720 | rs7896133 | 3.6 × 10−5 | 66 |

| ABCB1 | chr7:87037500 | rs2235015 | 1.8 × 10−2 | 58 |

| APOE | chr19:50009030 | rs8101274 | 1.4 × 10−2 | 34 |

| CALU | chr7:128183918 | rs3778760 | 1.9 × 10−2 | 46 |

| CAR | chr1:159545301 | rs12065184 | 9.9 × 10−3 | 50 |

| CYP1A1/CYP1A2 | chr15:72929814 | rs2305668 | 1.4 × 10−1 | 26 |

| CYP2A6 | chr19:46103074 | rs8109507 | 6.5 × 10−2 | 32 |

| CYP3A4/CYP3A5 | chr7:99104254 | rs4646450 | 1.1 × 10−1 | 29 |

| EPHX1 | chr1:224132378 | rs360097 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 52 |

| F7/F10/PROZ | chr13:112818877 | rs488703 | 1.7 × 10−1 | 40 |

| F2 | chr11:46651990 | rs13448 | 4.8 × 10−2 | 17 |

| F5 | chr1:167880418 | rs10919202 | 2.6 × 10−3 | 92 |

| F9 | chrX:138359434 | rs17002122 | 1.7 × 10−2 | 37 |

| GAS6 | chr13:113538172 | rs9550270 | 1.2 × 10−1 | 29 |

| GGCX | chr2:85677762 | rs6643 | 2.4 × 10−2 | 30 |

| NQO1 | chr16:68302646 | rs1800566 | 1.7 × 10−1 | 18 |

| NR1I2 | chr3:120890093 | rs2137619 | 1.8 × 10−2 | 35 |

| ORM1/ORM2 | chr9:116072082 | rs1490740 | 3.6 × 10−3 | 102 |

| PROC | chr2:127941698 | rs7590705 | 5.7 × 10−2 | 29 |

| PROS | chr3:95221384 | rs13071953 | 8.0 × 10−2 | 13 |

| SERPINC1 | chr1:172126805 | rs16846546 | 1.5 × 10−2 | 18 |

Candidate genes were clustered if their boundaries were within 100 kb, with the exception of CYP2C9, where specific polymorphisms are listed.

Coordinate for hg18; see http://genome.ucsc.edu.

Best P value within 100 kb of gene or gene cluster.

rs10871454 is perfectly correlated with rs9923231 (aka VKORC1 −1639) in the index population.

The highest-scoring polymorphism based on P values outside of these 2 known loci was located on chromosome 4 near the FGFBP2 gene (rs2286461), with P = 6.6 × 10−7 (Table 1). Multivariate analyses provided similar general results (data not shown), with no SNPs achieving genome-wide significance. The top ranked SNP under the multivariate model had a P value of 1.5 × 10−6 and was located near the telomere on chromosome 16p (rs11865472).

Replication results

Strong replication of both the VKORC1 (best UF + VU, P = 1.0 × 10−22) and CYP2C9 (best UF + VU, P = 1.2 × 10−8) associations was achieved in the replication populations, with the best combined (all samples) P values of 4.7 × 10−34 and 6.2 × 10−12 for VKORC1 and CYP2C9, respectively (Table 1). A selected list of the top 25 SNPs (excluding locally correlated variants) with the lowest P values in the index patient set is shown in Table 1. No SNPs replicated at a P value less than 10−4. One SNP (rs2859720) had a replication P value of 4.3 × 10−4; however, the allele effect was in the opposite direction to that predicted in the index population and was inconsistent within the 2 separate replication panels (data not shown). No replication was observed for SNPs chosen from dominance models or those testing for interaction effects with VKORC1 or CYP2C9 (data not shown).

Analysis of the full list of replication SNPs (355 total) after combining the index and replication panels identified one potentially interesting variant, rs216013, located within an intron of a membrane calcium-channel gene CACNA1C. This SNP was correlated with warfarin dose (P = 9.2 × 10−5) in the index population (not shown in Table 1). Combined analysis of the index and replication populations yielded a P value of 8.6 × 10−7. However, this variant did not reach our established significance threshold independently in the replication population (P = .002), nor did it achieve significance after multiple testing correction in multivariate modeling (uncorrected P = .003).

A multivariate model, including age, gender, treatment with amiodarone, treatment with losartan, VKORC1 genotype (rs9923231), and CYP2C9 carrier status (either *2 or *3), in the combined populations (n = 554) predicted approximately 41.2% of the total variance in stabilized dose. Including patient weight (n = 507) increased the total predicted dose variance to approximately 47%. Dose variance explained by VKORC1 and CYP2C9 was 25% and 9%, respectively, confirming and refining previous estimates.10,19

Genotype imputation using data from the European HapMap (CEPH European) SNPs and additional variants from approximately 1000 selected candidate genes26,27 expanded our tests of association in the index population to more than 3 million SNPs across the human genome. However, no significant SNPs outside of those previously described gave robust signals for association. Imputation methods resulted in tests for more than 5000 SNPs within 50 kb of a previously defined candidate genes.17 This is in contrast with 539 SNPs directly genotyped by the HumanHap 550K chip that are near these same candidate genes.

Discussion

This study is, to our knowledge, one of the first GWASs for a drug response and is the first such analysis for stabilized warfarin dose. Our findings confirmed known polymorphisms in CYP2C9 and VKORC1 as the primary genetic determinants of stabilized warfarin dose and should be considered the major genetic factors in the development of clinical dosing algorithms.

GWAS is a general approach that can identify common genetic associations provided there is sufficient power (ie, adequate sample size) to detect the desired effect and that genomic coverage is high. Using a strict genome-wide preliminary threshold of P less than 10−7, we had 84% and 97% power to detect a SNP association explaining 20% and 25%, respectively, of the variance in warfarin dosing.28 However, it is important to note that these power calculations are conservative, as they apply only to the discovery of variants in our index population at a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level and in the absence of replication. Actual power is much higher. Consider our robust detection of common variants in VKORC1 associated with dose, with correlation significance estimates 5 orders of magnitude below our genome-wide threshold (Figure 1). Furthermore, we selected all variants with an index population P value of less than 10−4 from any genetic model for replication to lower the false-negative rate. Even without prior hypotheses, for example, the effect of genetic variation in CYP2C9 (∼9% of the variance in dose) would have been detected in our experimental design (eg, rs4086116, with P values of 8.3 × 10−5, 1.2 × 10−8, and 6.2 × 10−12 in the index, replication, and combined populations, respectively. Thus, the power of this relatively small index patient population is consistent with our stated goal of identifying polymorphisms with relatively large effect that could subsequently be incorporated into pharmacogenetic algorithms.

The density and coverage of the polymorphism set used (HumanHap 550K) are substantial and represent approximately 90% of the common SNP variation in white patients as determined by the HapMap.22 One significant limitation is the extent to which common copy-number variants are captured. Although some copy number variants probably have been assessed in our study via linkage disequilibrium with a genotyped SNP,29 such sites are underrepresented on SNP arrays and may have an important influence.30 To expand our coverage to additional sites of SNP variation, we used imputation methods to extend our results genome-wide (∼6-fold increase in raw SNP count; ∼500,000 to 3 million) and specifically in warfarin-related candidate genes (∼10-fold increase; ∼500 to 5000). Imputation analysis, however, did not identify any polymorphisms beyond what we included in our replication study. It should be noted that the results given in Table 2 represent the best set of polymorphisms in candidate genes as determined here, and some of these may explain a smaller variance in warfarin dosing that we could detect independently (>7%-10%) in our study. However, coupled with observations from previous studies31,32 and the special emphasis placed here on candidate genes, both in terms of reduced initial significance thresholds (“Statistical analysis”) and elevation in the density of imputed SNPs, we conclude that common variation in candidate genes is particularly unlikely to have a large effect for this phenotype.

In a full combined analysis (all patients), the best novel SNP is located in an intron of CACNA1C and exhibited a P value slightly less than 10−6 (rs216013; P = 8.6 × 10−7). However, because this polymorphism was not significant using our established thresholds and less significant under a full multivariate model, additional replication will be required to assess its potential influence. In addition, it is worth noting that, even if the association is subsequently proven to be robust, the effects of this variant on warfarin dosing would be small (< 1% of the total variance). In this regard, our data constitute a good resource for validating other studies to identify polymorphisms with small effects. Although these variants have weak clinical utility, they may reveal new insights into warfarin pharmacology and highlight candidates for targeted rare variation discovery. For example, a recent study focused on genes involved in drug metabolism identified a nonsynonymous variant (rs2108622) in a cytochrome P450 gene, CYP4F2, that has a small (1%-2%) effect on warfarin dose.33 This variant was genotyped as part of our genome-wide analysis in our index population. We find that, although the P value is only nominally significant (.043 in a univariate additive model), the magnitude and direction of the effect are similar in our data, with each copy of the minor allele elevating dose by approximately 0.5 mg/day (data not shown). Thus, our data can be used to rapidly test hypotheses generated by other studies and confirm even very small effects.

In conclusion, clinical testing to determine the utility of known large effect polymorphisms has only recently begun. Our study provides important and reassuring feedback confirming the choice of genetic covariates for pharmacogenetic directed warfarin testing. The outcome of large clinical trials should produce meaningful and definitive results that will not have to be reconsidered in the future by incorporating other large genetic effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge D. Crawford for critical reading and comments and M. Wong and E. Johanson for technical assistance in the analysis and generation of the genome-wide genotype data. Funding for this work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS053646 (M.J.R.), GM68797 (A.E.R.), U01 GM074492 (J.A.J.), PGRN U01 HL65962 (D.M.R.), a Merck, Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund Postdoctoral Fellowship (G.M.C.), and the University of Washington School of Pharmacy Drug Metabolism, Transport and Pharmacogenomic Research program, which is sponsored by unrestricted gifts from the pharmaceutical industry (A.E.R., D.L.V.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: G.M.C., M.J.R., and A.E.R. designed the research study; G.M.C. and M.J.R. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; J.A.J., T.Y.L., H.F., U.I.S., M.D.R., C.M.S., and D.M.R. provided replication patient data and analysis; G.M.C., I.B.S., J.D.S., and M.J.R. performed data analysis on the index patient data; and J.A.J., D.M.R., A.E.R., and D.L.V. provided critical review of and revisions to the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mark J. Rieder, University of Washington, Department of Genome Sciences, Box 355065, Seattle, WA 98195; e-mail: mrieder@u.washington.edu.

References

- 1.Rettie AE, Tai G. The pharmocogenomics of warfarin: closing in on personalized medicine. Mol Interv. 2006;6:223–227. doi: 10.1124/mi.6.4.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rieder MJ. Pharmacogenetics of warfarin for potential clinical application. Curr Cardiovasc Rep. 2007;1:420–426. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford DC, Ritchie MD, Rieder MJ. Identifying the genotype behind the phenotype: a role model found in VKORC1 and its association with warfarin dosing. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8:487–496. doi: 10.2217/14622416.8.5.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fihn SD, Callahan CM, Martin DC, McDonell MB, Henikoff JG, White RH. The risk for and severity of bleeding complications in elderly patients treated with warfarin: the National Consortium of Anticoagulation Clinics. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:970–979. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-11-199606010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rettie AE, Haining RL, Bajpai M, Levy RH. A common genetic basis for idiosyncratic toxicity of warfarin and phenytoin. Epilepsy Res. 1999;35:253–255. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(99)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takanashi K, Tainaka H, Kobayashi K, Yasumori T, Hosakawa M, Chiba K. CYP2C9 Ile359 and Leu359 variants: enzyme kinetic study with seven substrates. Pharmacogenetics. 2000;10:95–104. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li T, Chang CY, Jin DY, Lin PJ, Khvorova A, Stafford DW. Identification of the gene for vitamin K epoxide reductase. Nature. 2004;427:541–544. doi: 10.1038/nature02254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rost S, Fregin A, Ivaskevicius V, et al. Mutations in VKORC1 cause warfarin resistance and multiple coagulation factor deficiency type 2. Nature. 2004;427:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature02214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Andrea G, D'Ambrosio RL, Di Perna P, et al. A polymorphism in the VKORC1 gene is associated with an interindividual variability in the dose-anticoagulant effect of warfarin. Blood. 2005;105:645–649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Gage BF, et al. Effect of VKORC1 haplotypes on transcriptional regulation and warfarin dose. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2285–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joffe HV, Xu R, Johnson FB, Longtine J, Kucher N, Goldhaber SZ. Warfarin dosing and cytochrome P450 2C9 polymorphisms. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:1123–1128. doi: 10.1160/TH04-02-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higashi MK, Veenstra DL, Kondo LM, et al. Association between CYP2C9 genetic variants and anticoagulation-related outcomes during warfarin therapy. JAMA. 2002;287:1690–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schalekamp T, Brasse BP, Roijers JF, et al. VKORC1 and CYP2C9 genotypes and acenocoumarol anticoagulation status: interaction between both genotypes affects overanticoagulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlquist JF, Horne BD, Muhlestein JB, et al. Genotypes of the cytochrome p450 isoform, CYP2C9, and the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 conjointly determine stable warfarin dose: a prospective study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;22:191–197. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-9030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldwell MD, Berg RL, Zhang KQ, et al. Evaluation of genetic factors for warfarin dose prediction. Clin Med Res. 2007;5:8–16. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2007.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gage BF, Lesko LJ. Pharmacogenetics of warfarin: regulatory, scientific, and clinical issues. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008;25:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s11239-007-0104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadelius M, Chen LY, Eriksson N, et al. Association of warfarin dose with genes involved in its action and metabolism. Hum Genet. 2007;121:23–34. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0260-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Rettie AE. Gamma-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) tagSNPs have limited utility for predicting warfarin maintenance dose. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2227–2234. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aquilante CL, Langaee TY, Lopez LM, et al. Influence of coagulation factor, vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1, and cytochrome P450 2C9 gene polymorphisms on warfarin dose requirements. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JL, Horne BD, Stevens SM, et al. Randomized trial of genotype-guided versus standard warfarin dosing in patients initiating oral anticoagulation. Circulation. 2007;116:2563–2570. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz UI, Ritchie MD, Bradford Y, et al. Genetic determinants of response to warfarin during initial anticoagulation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:999–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eberle MA, Ng PC, Kuhn K, et al. Power to detect risk alleles using genome-wide tag SNP panels. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1827–1837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhangale TR, Rieder MJ, Nickerson DA. Estimating coverage and power for genetic association studies using near-complete variation data. Nat Genet. 2008;40:841–843. doi: 10.1038/ng.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu L, Martinez FD, Klimecki WT. Automated high-throughput sex-typing assay. Biotechniques. 2004;37:662–664. doi: 10.2144/04374DD01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Servin B, Stephens M. Imputation-based analysis of association studies: candidate regions and quantitative traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livingston RJ, von Niederhausern A, Jegga AG, et al. Pattern of sequence variation across 213 environmental response genes. Genome Res. 2004;14:1821–1831. doi: 10.1101/gr.2730004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford DC, Akey DT, Nickerson DA. The patterns of natural variation in human genes. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005;6:287–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:149–150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444:444–454. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kidd JM, Cooper GM, Donahue WF, et al. Mapping and sequencing of structural variation from eight human genomes. Nature. 2008;453:56–64. doi: 10.1038/nature06862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephens M, Scheet P. Accounting for decay of linkage disequilibrium in haplotype inference and missing-data imputation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:449–462. doi: 10.1086/428594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kathiresan S, Melander O, Guiducci C, et al. Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:189–197. doi: 10.1038/ng.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caldwell MD, Awad T, Johnson JA, et al. CYP4F2 genetic variant alters required warfarin dose. Blood. 2008;111:4106–4112. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-122010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.