Publishing in high-quality international journals is part of today's scientific zeitgeist and a challenge for researchers from developed and developing countries alike. However, competition to attract an editor's attention and to convince reviewers might be tougher for scientists from non-English speaking (NES) countries. As various authors have pointed out, the proficiency of the English language among a country's scientists could influence its scientific output (Man et al, 2004; Victora & Moreira, 2006; Meneghini & Packer, 2007; Vasconcelos et al, 2007). A recent econometric study, for example, stated that English proficiency is a significant factor for the performance of European science (Bauwens et al, 2007).

Performing research in one language and having to write manuscripts in another—nearly always English—is not an easy task. Some NES authors argue that they “don't compete on a level playing field when it comes to international science” and that “language and cultural barriers may be partly to blame” (Anon, 2002). However, it is not clear how much linguistic competence affects the visibility of research in NES countries. In particular, it is difficult to assess the link between a researcher's writing competence and established indicators of research output such as the number of publications and citations. Most countries do not maintain databases with comprehensive information about a researcher's academic profile and publication record, or they do not make this information publicly accessible.

In Latin America, Brazil is the only country to make such information available through the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq; Federal District, Brasilia). Using a subset of the national database, set up by the CNPq in 2005, we obtained data on 52,223 Brazilian researchers, including their publications in national and international journals, and their proficiency in foreign languages, including English. The information on English proficiency is based on a self-evaluation of four language skills—reading, speaking, listening and writing—each of which can be ranked as good, reasonable or poor.

We found that communication skills have an impact on the visibility of Brazilian science in English language journals. Among the researchers, only 17,665 (33.8%) consider themselves to be fully proficient in English with good writing, speaking, listening and reading abilities. Although a high level of proficiency in all four English skills is desirable, competence in writing is an essential component for visibility in academia. When we looked at the writing competence of Brazilian researchers alone, we found that 44.4% classify their writing skills as good, 35.2% consider their writing skills as reasonable and 13.0% concede to poor writing skills.

We analysed the further relationship between the writing competence of Brazilian researchers and scientometric indicators by combining CNPq's database with the Brazilian Science Indicators (BSI) database (Batista et al, 2006), which contains information on the publications by Brazilian authors in the ISI Web of Knowledge from 1945 to 2004. BSI contains 188,909 references and includes information on the type of publication, the full reference, the citations per author per year up to June 2005, the authors' names and addresses, institutions, cities, states and countries. We analysed 150,323 research articles, 24,164 meeting abstracts, 5,541 notes, 3,577 letters and 2,333 reviews. CNPq's database contains information on publications by all Brazilian researchers with a PhD, whereas only 22,900 Brazilian authors are present in BSI, meaning that only 44.7% of authors from CNPq's database have published in ISI-indexed journals. Among these 22,900 authors, 51.4% classify their writing skills as good, 34.0% consider their writing skills as reasonable and 9.5% admit to poor writing skills.

Our data show that the number of publications in ISI-indexed journals for these BSI authors is associated with their writing competence. We found that researchers with good writing skills are considerably more productive—as measured by the number of papers—than those with reasonable or poor writing skills.

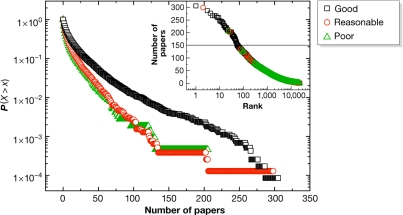

Fig 1 shows the complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF) of authors in BSI according to the total number of papers (Np). For CCDF analysis, data were normalized by the total number of authors in each group. In all graphs, P (X > x) is the probability that the variable X—the total number of researchers with a given number of papers in each group—will be higher than the given value on the x-axis. The CCDF is calculated as follows: Fc(x) = P(X > x) = 1 − F(x). To distinguish the performance of authors with various writing abilities, we assigned them to three groups: good, reasonable and poor.

Figure 1.

Complementary cumulative distribution function of researchers with different writing competences, good (black squares), reasonable (red circles) and poor (green triangles), according to the number of papers. Inset shows all authors in the BSI database according to rank.

We found that the number of papers correlates with writing skills. Authors with poor and reasonable writing skills are concentrated at the lower range from 0 to 125; above this range, authors with good writing competence are prevalent. Researchers with good writing competence cover the entire range of publications, in contrast to the other groups. The inset of Fig 1 (graph plotted in log scale) shows all 22,900 authors ranked by productivity (Np). A cut-off line drawn at the halfway point in the range of Np shows that researchers with good writing competence (black squares) are prevalent and achieve the top rank on a numerical basis.

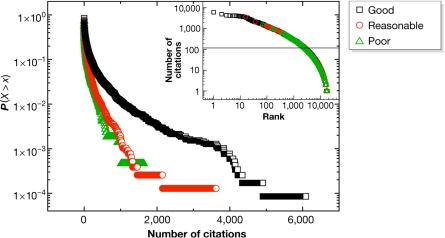

Similarly, we analysed the visibility and impact of Brazilian research as measured by citations. As expected, citations are more numerous for those with good writing competence (Fig 2). Note the similarity between the curves showing the citation profile for authors with poor and reasonable writing skills.

Figure 2.

Complementary cumulative distribution function of researchers with different writing competences, good (black squares), reasonable (red circles) and poor (green triangles), according to the number of citations. Inset shows all authors in the BSI database according to rank.

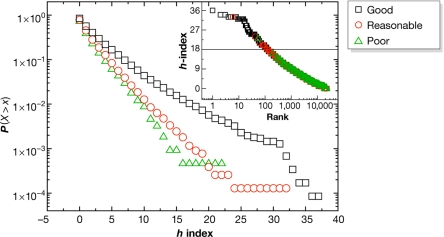

As the number of papers and citations might be insufficient to measure a researcher's performance (Moed, 2005), we also looked at the so-called Hirsch or h index for these BSI authors (Hirsch, 2005), as it combines an individual researcher's output and the impact of his or her contributions (Fig 3). According to Hirsch, “a scientist has index h if h of his or her papers have at least h citations each and the other (Nph) papers have fewer than h citations each.” Despite criticisms (Kelly & Jennions, 2007), the h index has been accepted as an accurate indicator of a scientist's visibility, even across different research fields (Ball, 2005). Again, higher h-index values relate to researchers with good writing competence. The inset of Fig 3 shows that above the cut-off line, where h-index values are higher, authors with good writing competence are prevalent.

Figure 3.

Complementary cumulative distribution function of researchers with different writing competences, good (black squares), reasonable (red circles) and poor (green triangles), according to h indices. Inset shows all authors in the BSI database according to rank.

These findings raise at least two intriguing issues. The first concerns the contribution of Brazilian researchers to science in general. Stolerman & Stenius (2008) have discussed “lost” science in the context of language barriers, citing, for example, groundbreaking pharmaceutical research that took years to reach the international scientific community and benefit society simply because it was published in French. They suggest that publishing in local journals in the authors' native language might hinder the progress of science in some areas. As English is the lingua franca of science, NES researchers are also expected to disseminate their findings in English; however, this is still a serious hurdle for many of these authors (Freeman & Robbins, 2006). Meneghini & Packer (2007) argue that “scientists […] hope to attract a larger regional audience by publishing in their mother tongue or they choose a national journal because they are not sufficiently fluent in English.”

The second intriguing issue concerns Latin-American science. In our study, we focused on Brazil, but the situation is similar to that of other Latin-American countries. In addition to speaking different languages—Portuguese or Spanish—most of these countries do not use English even as a third official language. Furthermore, developing the linguistic competence for writing research papers is not part of the academic tradition of most of their universities and funding to provide writing support for Latin-American scientists is scarce. According to Hermes-Lima et al (2007), Research & Development spending in Latin America between 1990 and 2004 ranged from 0.48 to 0.56% of GDP, which is “much smaller than that in developed countries”. Writing a publication for an English language international journal is a linguistic burden that most scientists from Latin America have to bear themselves. These constraints might affect the visibility of Latin-American science—an issue that calls for government attention.

Nevertheless, it seems that these problems have gone unnoticed. Brazil's president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva announced “a remarkable US$28-billion package for science and technology over the next three years […] equivalent to 1.5% of the country's GDP” (Medeiros, 2007). Increasing research spending from 1.0 to 1.5% of GDP is likely to boost science, technology and innovation in Brazil. However, our data indicate that language matters in Brazilian science and they point to a linguistic handicap that has been overlooked. Thus we believe that improving the writing competence of Latin America's scientific community should not be a minor issue in policy-making. Increasing the number of researchers who are fully proficient in English might help to enhance international awareness of this region's scientific contributions.

This equation might hold true even for more advanced countries, for example in Europe. Bauwens et al (2007) predict that “if France were to improve its English proficiency by 10% […] the number of French HCRs [highly cited researchers] would increase in the long run by 25%.” Our data do not provide an estimate of the possible increase in Brazil's percentage share of international publications and citations, nor an estimate of an increase in the average Brazilian researcher's h index. However, they offer some insight into the influence of good English proficiency on scientific productivity in an international setting. This calls for further studies to assess the extent to which the writing competence of researchers might be a bottleneck in the publication and visibility of science from Latin America.

Finally, we argue that this is not an issue for just Latin America. In South Korea, Japan and Europe, research seems to be affected by the constraints imposed by the current “English-dominated setting for science” (La Madeleine, 2007). As Frank Gannon commented in a recent editorial in this journal: “…we—those of us who grew up speaking English—greatly underestimate the extent of these difficulties for non-native speakers. I lived in France and Germany for many years, but I would have writer's block if I had to write something—let alone a scientific paper—in either language” (Gannon, 2008).

Acknowledgments

We thank CNPq, especially Felizardo P. da Silva, Silvana M. Cosac and Cristiano L. Kuppens.

References

- Anon (2002) Breaking down the barriers. Nature 419: 863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball P (2005) Index aims for fair ranking of scientists. Nature 436: 900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista PD, Campiteli GM, Kinouch O, Martinez SA (2006) Is it possible to compare researchers with different scientific interests? Scientometrics 68: 179–189 [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens L, Mion G, Thisse JF (2007) The Resistible Decline of European Science. CORE Discussion Paper from the Belgian Program on Interuniversity Poles of Attraction. University of Leuwen, Belgium: Center for Operations Research and Econometrics. www.core.ucl.ac.be/ [Google Scholar]

- Freeman P, Robbins A (2006) The publishing gap between rich and poor: the focus of AuthorAID. J Public Health Policy 27: 196–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon F (2008) Language barriers. EMBO Rep 9: 207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes-Lima M, Alencastro AC, Santos NC, Navas CA, Beleboni RO (2007) The relevance and recognition of Latin American science. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 146: 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JE (2005) An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16569–16572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CD, Jennions MD (2007) H-index: age and sex make it unreliable. Nature 449: 403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Madeleine BL (2007) Lost in translation. Nature 445: 454–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man JP et al. (2004) Why do some countries publish more than others? An international comparison of research funding, English proficiency and publication output in highly ranked general medical journals. Eur J Epidemiol 19: 811–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros J (2007) Brazil to boost science spend. Nature 450: 591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini R, Packer AL (2007) Is there science beyond English? EMBO Rep 8: 112–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moed HF (2005) Citation Analysis in Research Evaluation. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, Stenius K (2008) The language barrier and institutional provincialism in science. Drug Alcohol Depend 92: 3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos SMR, Leta J, Sorenson MM (2007) Scientist-friendly policies for non-native English-speaking authors: timely and welcome. Braz J Med Biol Res 40: 743–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora CG, Moreira CB (2006) North–south relations in scientific publications. Rev Saude Publica 40: 36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]