Abstract

BtuB is a TonB-dependent transport protein that binds and carries vitamin B12 across the outer membrane of Gram negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli. Previous work has demonstrated that the Ton box, a highly conserved segment near the N-terminus of the protein, undergoes an order-to-disorder transition upon the binding of substrate. Here we incorporate pairs of nitroxide spin labels into membrane reconstituted BtuB and utilize a four-pulse double electron-electron resonance (DEER) experiment to measure distances between the Ton box and the periplasmic surface of the transporter with and without substrate. During the reconstitution, the labeled membrane protein was diluted with wild-type protein, which significantly reduced the intermolecular electron spin-spin relaxation rate and increased the DEER signal-to-noise ratio. In the absence of substrate, each spin pair gives rise to a single distribution of distances that is consistent with the crystal structure obtained for BtuB; however, distances that are much longer are found in the presence of substrate, and the data are consistent with the existence of an equilibrium between folded and unfolded states of the Ton box. From these distances, a model for the position of the Ton box was constructed, and indicates that the N-terminal end of the Ton box extends approximately 20 to 30 Å into the periplasm upon the addition of substrate. We propose that this substrate-induced extension provides the signal that initiates interactions between BtuB and the inner membrane protein TonB.

TonB-dependent transporters are a unique class of high-affinity transport proteins found in the outer membrane (OM) of Escherichia Coli and other Gram-negative bacteria. In these systems, energy for transport is extracted from the proton potential across the inner membrane by coupling to the inner membrane protein TonB. Crystal structures have been obtained for a number of TonB-dependent transporters, including the iron transporters FhuA (1, 2), FepA (3), FecA (4) and the vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin (CNCbl)) transporter BtuB (5). These membrane transporters have homologous structures formed from a 22-stranded β-barrel where the N-terminal region of the protein forms a core (or hatch) that occludes the interior of the barrel (see Figure 1).

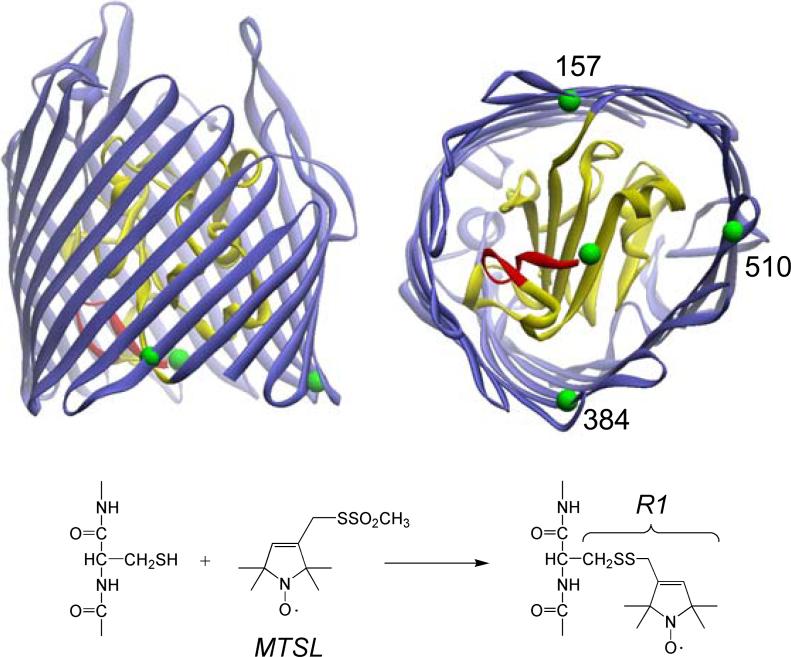

Figure 1.

Top: two views of the crystal structure for BtuB in the absence of substrate (PDB ID : 1NQE). Residues 6−17 are shown in red, and the hatch or core region is shown in yellow. The green spheres represent the van der Waals surfaces of the Cα carbons of residues that were mutated to cysteine. These include residues D6 (in the Ton box), Q157, R384 and Q510 (in the β-barrel). Bottom: each of these were mutated, expressed and labeled singly and in pairs (see text) using the sulfhydryl specific MTSL to produce the spin-labeled side chain R1.

At the present time, the mechanism of transport in TonB-dependent systems is unclear. Coupling between the transporter and TonB is thought to take place through a conserved sequence near the N-terminus termed the Ton box, and there is evidence for an interaction between the transporter and TonB, that is substrate-dependent (6-8). The nature of the substrate-dependent change that triggers the Ton box interaction is not entirely clear. The Ton box is not resolved in the crystal structure of FhuA, either with or without substrate. In FecA, the Ton box is resolved, but is not resolved when substrate is bound. In BtuB, the crystal structures show a minor change in the Ton box configuration with substrate addition, but it is resolved and remains folded within the barrel of the protein. The results of site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) present a different picture for the Ton box of BtuB, where the Ton box is seen to undergo an order-to-disorder transition upon the addition of substrate (9, 10). The discrepancy between the two methods appears to be the result of different osmolalities for the buffers that are used in the crystallographic versus the spectroscopic approach (11, 12).

Earlier SDSL studies indicated that the Ton box became disordered upon the addition of substrate, and presumably had greater access to the periplasmic space; however, no direct evidence for the position or placement of the Ton box upon substrate addition was obtained in these measurements (9, 10). In the present work, we investigate the position of the Ton box of BtuB in the presence and absence of substrate using the four pulse double electron-electron resonance (DEER) measurement (13). This method produces a dipolar echo that is modulated by the frequency of the dipolar interaction between spin pairs, and it has been used to measure distances out to 80 Å (14). To make these measurements, three pairs of spin labels were incorporated into BtuB, where one label in the pair was placed on the periplasmic surface of the barrel of BtuB (at positions 157, 384 or 510) and the other was placed within the BtuB Ton box (at position 6, see Figure 1). The data indicate that the N-terminal end of the Ton box undergoes a dramatic change in position upon the addition of substrate, so that it projects as much as 30 Å into the periplasmic space. The data are also consistent with an equilibrium between folded and unfolded conformations of the Ton box. A model for the Ton box has been constructed, which is consistent with the results of previous CW EPR studies and with the results of the pulse measurements presented here. We propose that the extension of this unstructured protein segment provides the trigger that initiates the protein-protein interaction between BtuB and TonB.

Experimental

Materials

The sulfhydryl reactive spin-labeled methanethiosulfonate, (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-3-pyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate (MTSL), was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Ontario, Canada). Cyanocobalamin, Polyethylene glycol 3350 (PEG 3350, Avg. Mol. Wt.=3350) and DL-dithiothreitol (DTT) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Sarkosyl was from Fisher Chemical Co. (Pittsburgh, PA), and 4-(-2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonylfluoride (AEBSF) was purchased from EMD Bioscience, Inc (La Jolla, CA). Octylglucoside, (OG, Anagrade) was purchased from Anatrace (Maumee, OH) and 1-Palmitoyl-2-Oleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine (POPC), was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Coomassie Plus, Slide-A-lyzer Dialysis Cassettes (10,000 Da molecular weight cut-off) were purchased from Pierce Biotechnology, Inc (Rockford, IL), and Centriprep YM30 was purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA). Glass (0.6 mm I.D.) and quartz capillaries (1.5 mm I.D.) were purchased from VitroCom Inc. (Mt. Lakes, NJ).

Methods

Mutagenesis and isolation of intact outer-membranes

Both single and double cysteine mutants (D6C, Q157C, R384C, Q510C, D6C/Q157C, D6C/R384C, D6C/Q510C and D6C/T55C) of BtuB were produced by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit by Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The mutants were then expressed in Escherichia coli strain RK5016 (metE). Cell growth, isolation of intact outer-membranes, solubilization and purification procedures were as described previously (15, 16), except that phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was replaced by AEBSF and spin labeling was performed differently. Following the first ion-exchange chromatography step, fractions containing BtuB (approximately 20−35 ml) were collected and additional OG was added to ensure that the protein remained soluble. The pH was adjusted to 8.0 by adding 100 mM Tris-buffer (pH 8.0) containing 6 mM DTT, and was concentrated to approximately 2 ml using a Centriprep YM30. The BtuB sample was then spin labeled by adding 100 μl of 22 mM MTSL to the protein solution, which was allowed to react for 2−4 hours at room temperature. The sample was then subjected to a second round of ion-exchange chromatography to remove excess spin label. Wild-type BtuB (WT) was purified without spin labeling. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford assay (17, 18).

The purified protein was then reconstituted into vesicles by dialysis from OG mixed micelles as described previously (16), except that spin-labeled BtuB was diluted prior to reconstitution with wild-type protein. The spin pair, D6C/T55C was produced, and used to characterize the DEER signal under different dilutions with wild-type protein. However, the distances measured in the presence of substrate were greater than 4.5 nm and beyond a distance that could be accurately determined with the sample preparation and experimental conditions used here. Typically, the double-labeled mutants were mixed with wild-type (non-spin labeled BtuB) at a ratio of 1:3. Prior to dialysis, mixed micelles contained POPC/BtuB = 25:1 (w/w) and OG/POPC = 10:1 (w/w). For measurements with substrate, Ca2+ and vitamin B12 were added to final concentrations of 4 and 1 mM, respectively. Under these conditions, the BtuB samples are completely saturated with substrate.

CW EPR measurements

CW-EPR spectroscopy was performed on a Varian E-line 102 series X-band spectrometer equipped with a loop-gap resonator (Medical Advances, Milwaukee, WI). LabView software, provided by Drs. Christian Altenbach and Wayne Hubbell (UCLA), was used for digital collection and analysis of data. All spectra for line shape analyses were recorded at 2.0 mW incident power with a modulation amplitude of 1.0 G, from samples in glass capillaries. Typically, 4−10 ul of the protein sample was used for CW EPR measurements, which were carried out at room temperature (approximately 295 K), and were averages of 16 scans (sweep width =100 Gauss).

Dipolar interactions measured using double electron-electron resonance

Four-pulse DEER measurements (13) were performed using a Bruker Elexsys 580 spectrometer equipped with a 2-mm split-ring resonator under conditions of strong overcoupling (Q =200). Measurements were performed at approximately 78K unless otherwise mentioned, using the pulse sequence (π/2)ν1 − τ1 − (π)ν1 − t − (π)ν2 − (τ1 + τ2 − t) − (π)ν1 − τ2 − echo. A π/2 pulse length of 16 ns was used at the observe frequency, ν1, and a π ELDOR pulse of 36 ns was found to be optimal for the pump frequency, ν2. Interpulse delays of τ1=200 ns and τ2=1200 ns were used with an increment Δt = 4 ns, unless otherwise noted. An 8-step phase cycle was applied during data collection. The observe frequency ν1 (typically 9.46 GHz) was set to the center of the resonator mode and the static magnetic field was adjusted to the global maximum of the nitroxide spectrum. The pump frequency ν2 (typically ν2 − ν1 = 72 MHz) was set to the local maximum at the low-field edge of the spectrum. Accumulation times for the data sets varied between 19 and 22 hours. Reconstituted BtuB samples used for DEER typically had a 12 μL volume at a protein concentration of 70 to 80 μM, and were placed in sealed quartz capillaries.

Analysis of dipolar evolution data

The DEER experiment provides a signal, V, of the form:

where ωdd is the frequency of the dipolar interaction (which is dependent upon the distance between spins, r, and the angle between the interspin vector and the magnetic field, θ), and t is the dipolar evolution time (14). The parameter λ defines the depth of the modulation in this signal. Distance distributions were determined from the dipolar time evolution data, V(t), using the MatLab program package DeerAnalysis 2006, provided by G. Jeschke (http://www.mpipmainz.mpg.de/∼jeschke/distance.html). The background contribution to the signal was fitted using a two-dimensional distribution (planar background correction) corresponding to exp(-kt⅔). The distance distribution P(r) was obtained by Tikhonov regularization (19, 20), and the optimal regulation parameter was chosen from the L-curve computed in the DeerAnalysis 2006 package, unless otherwise indicated. For cases where a distribution of distances was obtained, the distribution was fit to a series of Gaussians using Origin (Origin Lab Corp., Northhampton, MA). The relative areas under each Gaussian curve were used to estimate relative populations.

Results

EPR spectra of single and double spin labeled mutants of BtuB

To determine the position of the Ton box with and without substrate, three sets of double mutants were constructed where one label was incorporated into the N-terminal end of the Ton box at position 6, and the second label of the pair was located on one of three sites on the periplasmic side of the barrel, 157, 384 and 510 (see Figure 1). These proteins were then expressed, purified, spin labeled and reconstituted into POPC bilayers as described in Methods.

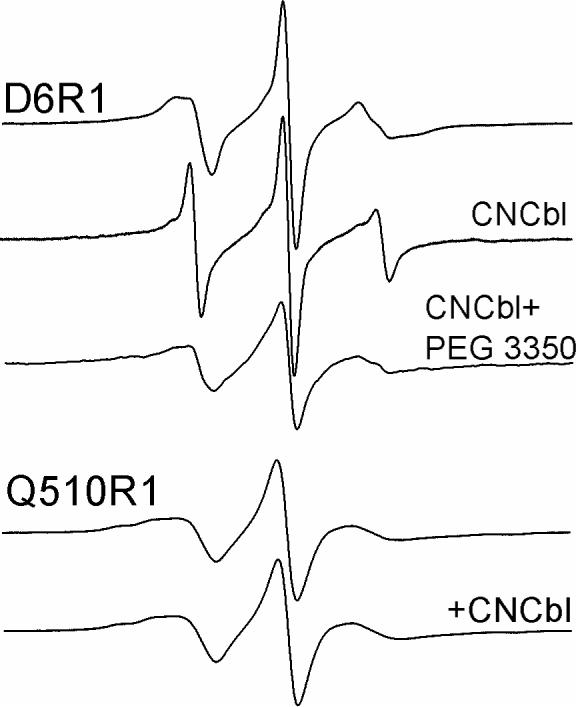

Shown in Figure 2 are X-band CW EPR spectra of the single labeled mutants D6R1 and Q510 R1. D6R1 on the end of the Ton box shows a dramatic change in EPR lineshapes upon the addition of substrate (CNCbl or vitamin B12). The change to a narrower lineshape with substrate addition reflects the conversion of the Ton box from a structured and folded segment to a highly flexible unfolded protein segment. This is consistent with previous work showing that the Ton box and the N-terminal end of BtuB unfold upon substrate binding to approximately residue 15 or 16 (9). If 30% PEG 3350 is added to the substrate-bound protein, the spectrum from D6R1 reverts to a broad line shape indicating that Ton box is refolded by this solute. This observation is consistent with previous work, which indicates that there is an equilibrium between folded and unfolded forms of the Ton box that is modulated by solution osmolality (12, 21). Figure 2 also shows EPR spectra for Q510R1. These lineshapes are similar to those seen at other β-sheet sites (22), and as expected, no substrate-dependent change in the EPR spectrum at this site is seen. Similar results are obtained for R384R1 and Q157R1 which are also located on the barrel (data not shown).

Figure 2.

EPR spectra of D6R1 reconstituted into POPC without (top trace) and with substrate (CNCbl), as well as with both substrate binding and PEG 3350 (30% w/v). Lower two traces: EPR spectra of Q510R1 reconstituted into POPC with and without substrate. Spectra are 100 Gauss scans.

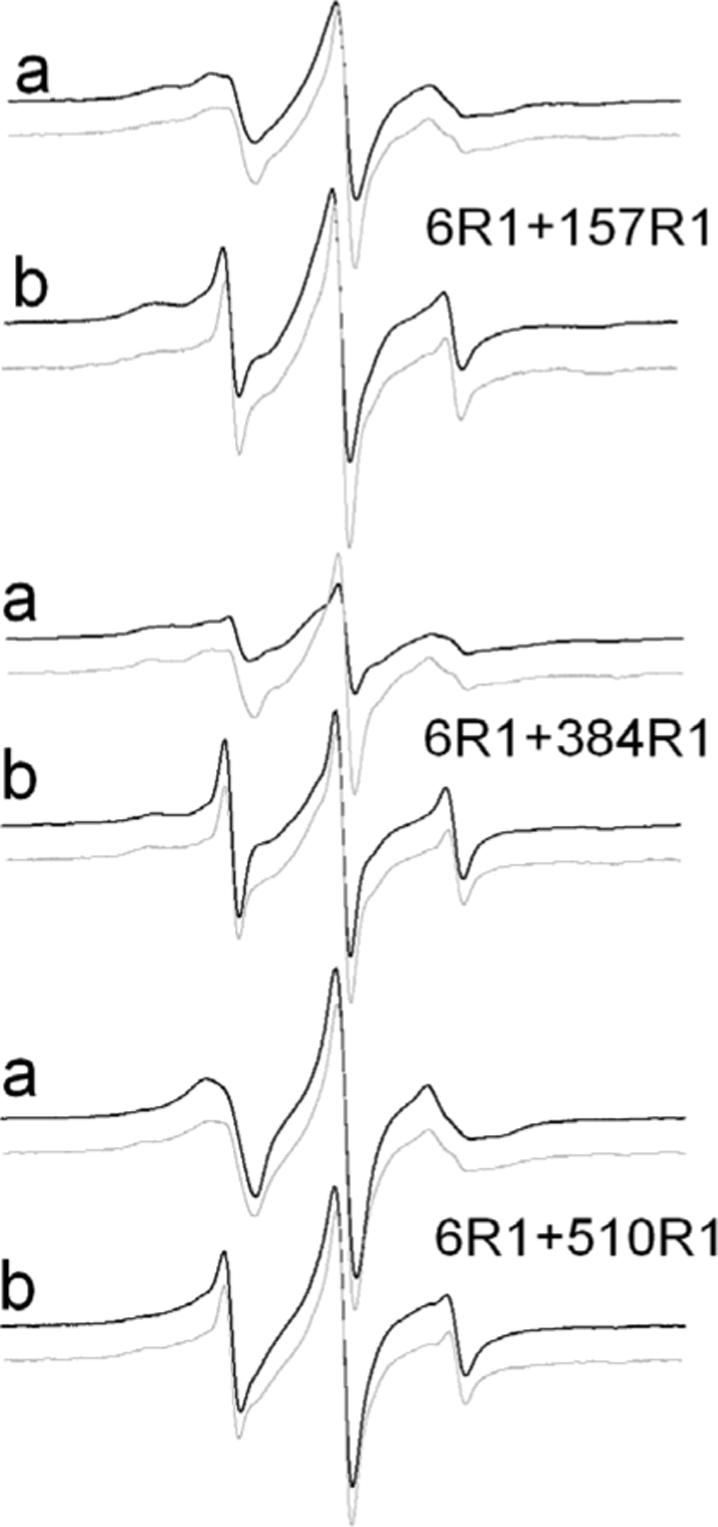

The CW EPR spectra of the three double spin-labeled BtuB derivatives are shown in Figure 3 (solid lines), both without (Figure 3a) and with (Figure 3b) substrate. Also shown in Figure 3 are the sum of the two single spectra (gray lines). Under each condition (with and without substrate), the EPR lineshapes for double mutants D6R1/Q510R1 and D6R1/Q157R1 are virtually identical to the two respective sums. This suggests that the static dipolar interaction between these nitroxide pairs is weak, and that inter-spin distances must be over 20Å (23). This is consistent with the Cα-Cα distances observed in the crystal structure of BtuB (Table 1). However, for the mutant pair D6R1/R384R1, the spectra are slightly broadened compared to the sum of the single spectra in the absence of substrate, which corresponds to a distance between the spin pair of approximately 20Å (23). This broadening is not seen once substrate is added, suggesting that substrate addition increases the distance between these nitroxides. As discussed below, this result is consistent with measurements made by DEER.

Figure 3.

EPR spectra of double spin labeled BtuB (black lines) (a) reconstituted in POPC vesicles and (b) in the presence of substrate. Also shown are the EPR spectra that are obtained by summing the normalized spectra corresponding obtained from each single mutant (gray lines). These spectra represent non-interacting spectra or spectra that would be obtained in the absence of dipolar interactions. In most cases, the spectra obtained from the double mutants closely match the non-interacting spectra, indicating that interspin distances are greater than 20 Å. The one exception is the spectrum from D6R1/R384R1 in the absence of substrate, where there is clear evidence of dipolar broadening.

Table 1.

Distances between positions from BtuB crystal structures.*

| Double Mutants | Cα-Cα Distance (nm) | Distance Change (liganded-apo) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apo | +Ca (CNCbl) | ||

| D6-Q157 | 2.15 | 2.61 | 0.46 |

| D6-R384 | 2.04 | 1.56 | −0.48 |

| D6-Q510 | 2.03 | 2.30 | 0.27 |

Distances are obtained from the crystal structures in the absence and presence of substrate: PDB ID : 1NQE and 1NQH, respectively (5).

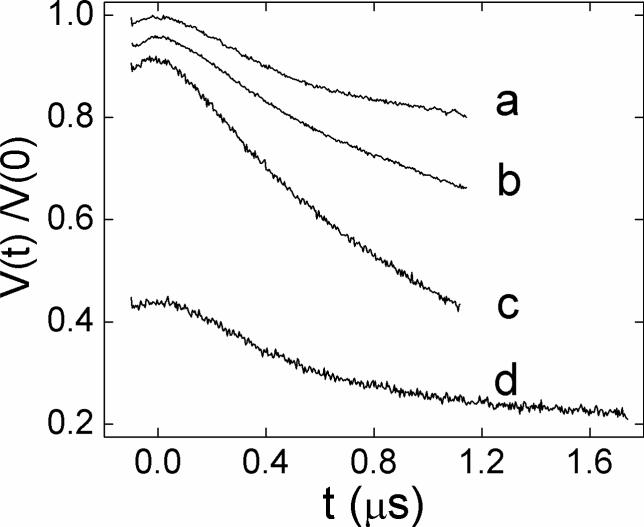

The time-domain DEER signals are improved by the use of magnetically dilute samples

Under the conditions typically used in our reconstitution, protein:lipid ratios were approximately 1:700 and relatively noisy DEER signals were obtained for some samples due to intermolecular dipolar interactions. In the present case, this difficulty was overcome by producing a reconstituted protein sample that was magnetically dilute. In particular, the spin-labeled protein was diluted with chromatographically pure wild-type protein. One advantage of this approach, compared to producing a highly dilute protein sample in membranes, is that identical reconstitution and membrane preparation procedures could be employed.

Figure 4 shows the four-pulse DEER time-domain data for D6R1/T55R1 in POPC vesicles at different ratios of labeled:WT protein. At a ratio of 1:1 (Figure 4c), the signal decay was approximately 50% of the maximum when t was 1200 ns, while at ratios of 1:3 and 1:6, the maximum signal was 70% (Figure 4b) and ∼80% (Figure 4a), respectively. With longer distances, it can be difficult to separate the desired dipolar signal from the background decay. As a result, we increased τ2 to 1800 ns and used a 1:6 ratio of labeled to WT protein with measurements involving longer distances, such as that for D6R1/T55R1 (Figure 4d). For shorter distances, a 1:3 ratio was sufficient to reduce the intermolecular dipolar-dipolar interaction so that the signal could be extracted from the background decay.

Figure 4.

Four-pulse DEER dipolar time evolution data for the double spin labeled BtuB mutant D6R1/T55R1 reconstituted into POPC vesicles at different local spin concentrations that are obtained by varying the labeled:wild-type protein ratio: (a) 1:6, (b)1:3, (c) 1:1 at τ2=1200 ns, and (d) 1:6 with τ2=1800ns. The y-axis for b, c and d are offset by 0.05, 0.1, and 0.45 for clarity.

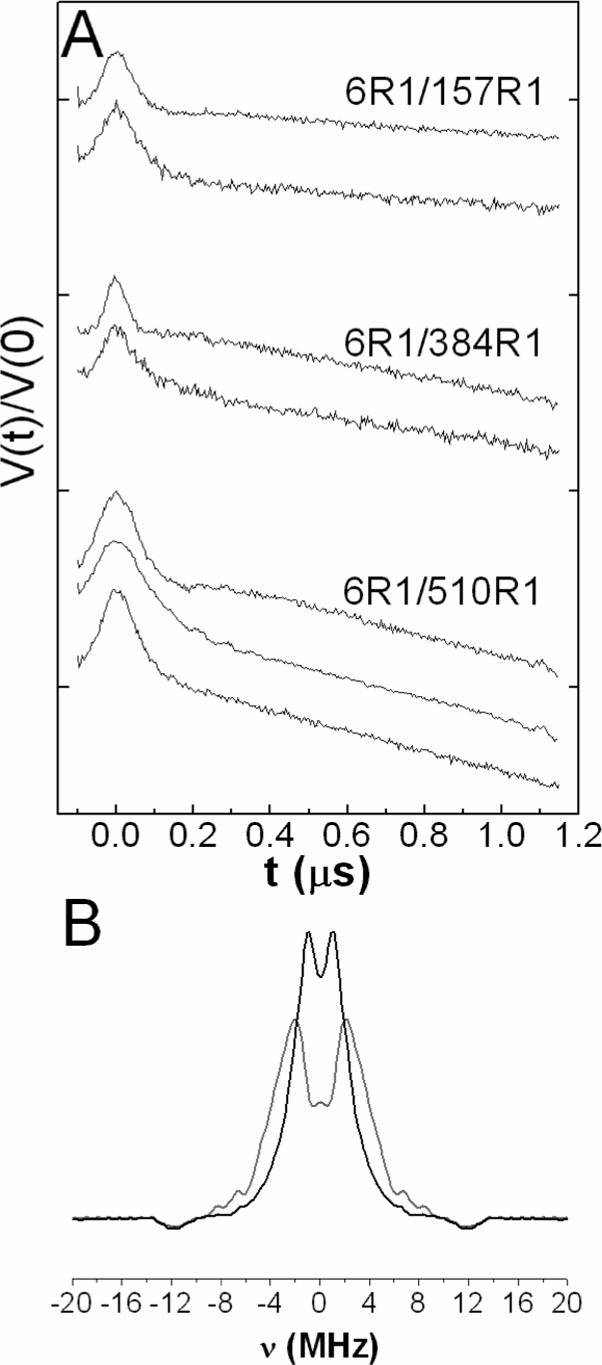

Four-pulse DEER reveals dramatic changes in the Ton box position upon substrate binding

The normalized DEER signals (V(t)/V(0)) are plotted in Figure 5A for D6R1/Q157R1, D6R1/R384R1, and D6R1/Q510R1 in the presence and absence of substrate, using a labeled:WT protein ratio of 1:3. For D6R1/Q510R1 spectra were also recorded in the presence of substrate and PEG 3350. Figure 5B, shows dipolar power spectra (Pake patterns) that are extracted from the data for D6R1/Q510R1 in the absence and presence of substrate. Figure 6 shows the corresponding interspin distance distributions obtained from the DEER signals in Figure 5A.

Figure 5.

(A) Four-pulse DEER dipolar time evolution data, V(t)/V(0), for double spin labeled BtuB derivatives. For D6R1/Q157R1 and D6R1/R384R1 top and bottom traces are without and with substrate (CNCbl), respectively. For D6R1/Q510R1 the top and middle traces are without and with substrate, respectively, and the bottom trace includes both substrate and 30% (w/v) PEG 3350. Each vertical division represents a change in V(t)/V(0) of 0.2, and the peak of each DEER signal corresponds to a normalized value of 1.0 (B) Dipolar powder spectrum (Pake pattern) extracted from the data in A) for D6R1/Q510R1 in the absence (gray line) and presence (black line) of substrate.

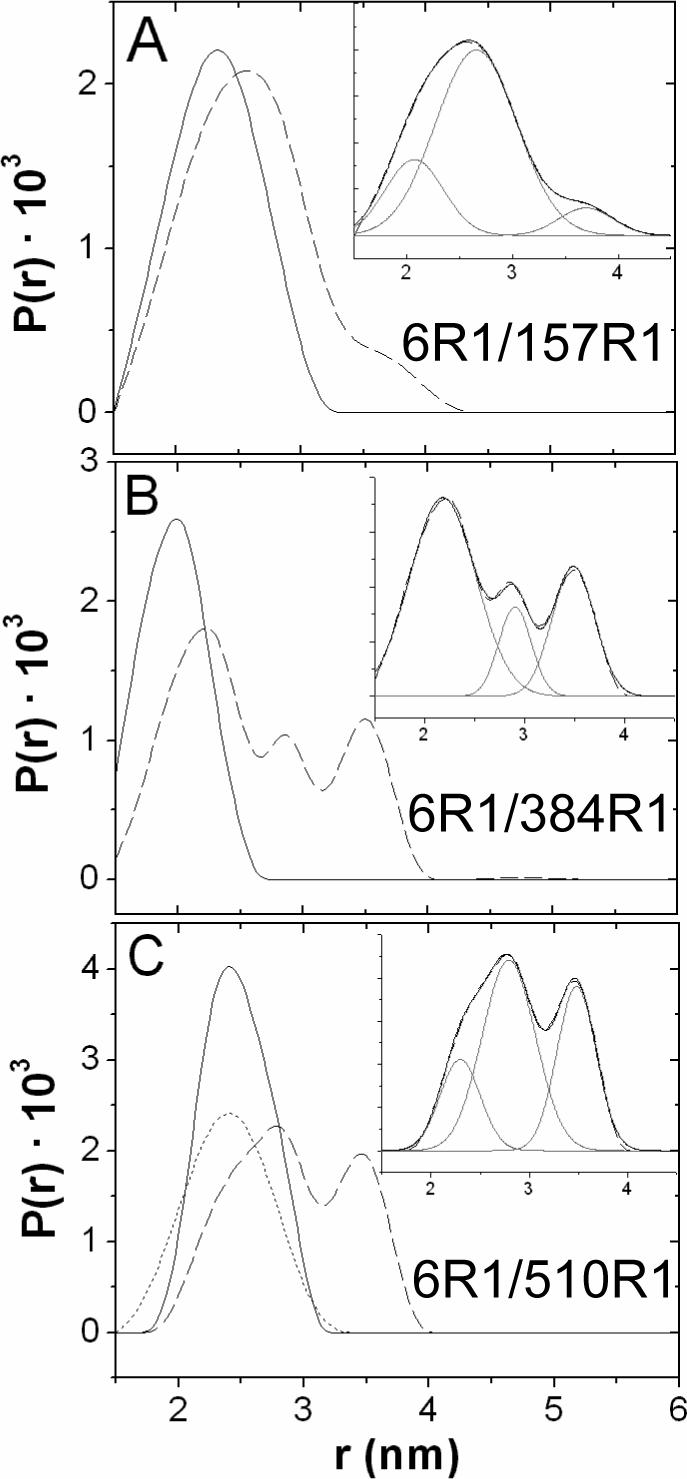

Figure 6.

Extracted distance distributions (P(r)) by applying Tikhonov regularization to the DEER data. (A) D6R1/Q157R1 with (dashed) and without (solid) substrate (B) D6R1/R384R1 with (dashed) and without (solid) substrate and (C) D6R1/Q510R1 with (dashed) and without (solid) substrate, and with both substrate and ∼ 30% (w/v) PEG 3350 (dotted). Insets are multi-Gaussian fits for the distance distribution in the presence of substrate, distance distribution curve (dashed), Gaussian curves (gray) and fit (black).

For each mutant, a single distance distribution is obtained in the absence of substrate. For D6R1/R384R1, the distance distribution is centered at approximately 2.0 nm (Figure 6A and Table 2), and a significant fraction of this distance lies at < 1.8 nm, which likely results in the line broadening seen in the CW-EPR (Figure 3). For D6R1/Q510R1, a single distribution centered at 2.47 nm is obtained, and for D6R1/Q157R1, a distance of 2.33 nm is found. In each case, these distances are within a few Angstroms of that seen for the Cα-Cα distances in the crystal structures (Table 1). Some differences between distances derived from EPR and from crystallography are expected. Although the R1 side chain has a preferred configuration relative to the protein backbone, it can execute motions about at least two of the bonds linking it to the protein backbone (24), and differences between the rotameric states of the two labels could easily account for the differences between the electron-electron distances and Cα-Cα distances.

Table 2.

Distances between spin pairs in BtuB derived from DEER*

| Label Pair | Distances (nm) (distribution (nm), fraction (%)) |

|---|---|

| D6R1/Q510R1 | |

| apo | 2.5 (0.27, 100%) |

| +CNCbl | 2.3 (0.2, 18%); 2.8 (0.54, 50%); 3.5 (0.4, 32%) |

| +CNCbl and PEG 3350 | 2.4 (0.33, 100%)† |

| D6R1/Q157R1 | |

| apo | 2.3 (0.34, 100%)† |

| +CNCbl | 2.1 (0.27, 21%); 2.7 (0.38, 72%); 3.7 (0.26, 7%)† |

| D6R1/R348R1 | |

| apo | 2.0 (0.24, 100%) |

| +CNCbl | 2.2 (0.33, 61%); 2.9 (0.16, 14%); 3.5 (0.21, 26%) |

Distance distributions were computed using Tikhonov regularization in DeerAnalysis 2006 with a 2-dimension background distribution. Multiple distance distributions were further fit into separate Gaussian peaks using Origin, and the percentage of each distance population was calculated by comparing the area under each Gaussian curve. The distance distribution represents the distance corresponding to one standard deviation from the peak of the distribution.

For these data, a regulation parameter of 1000 was used in the Tikhonov regulatization. For all other data, a value of 100 was used.

For each of the spin-labeled pairs, the addition of substrate results in a slower decay of the DEER signal, indicating an increase in the interspin distance (Figure 5A). This is most apparent for D6R1/R384R1 and D6R1/Q510R1. The corresponding distributions and distances are shown in Figure 6 and Table 2. Each of the insets in Figure 6 show distance distributions determined in the presence of substrate. In each case, the distance distribution appears to arise from more than one interspin distance, and in each case the data is fit well by three distances. One of these distances is close to the distance obtained in the absence of substrate, and the others are significantly longer than that seen in the substrate-free case by 5 to 15 Å (Table 2).

For D6R1/Q510R1, DEER data were also obtained in the presence of substrate following the addition of 30% PEG 3350. In this case, the addition of PEG eliminates the longer distances, to yield a single distribution of distances close to that seen in the folded (substrate-free) form of the Ton box. This is consistent with previous work indicating that high concentrations of these solutes act through and osmotic mechanism to shift the Ton box to its folded or least hydrated state (11, 12).

For DEER signals with good signal-to-noise, the distances can be estimated with good precision (approximately ±0.4 Å) (25); however, there is likely a much greater uncertainty in fitting the distance distributions, particularly those involving longer distances (19). As seen in Table 2, the populations of the distances in each of these sample shows considerable variability, and some of this variability is likely due to uncertainty in the fits. This variability might also result from differences in sample preparation, and the effects of the different nitroxide substitutions (in the β barrel) on the Ton box equilibrium (9). Nonetheless, the data from each of the three mutant pairs are consistent, and indicate that both folded and unfolded conformations of the Ton box are observed in the presence of substrate. And as discussed below, the appearance of these distance distributions is consistent with previous work from CW EPR indicating that there is an equilibrium between folded and unfolded Ton box forms (11, 12).

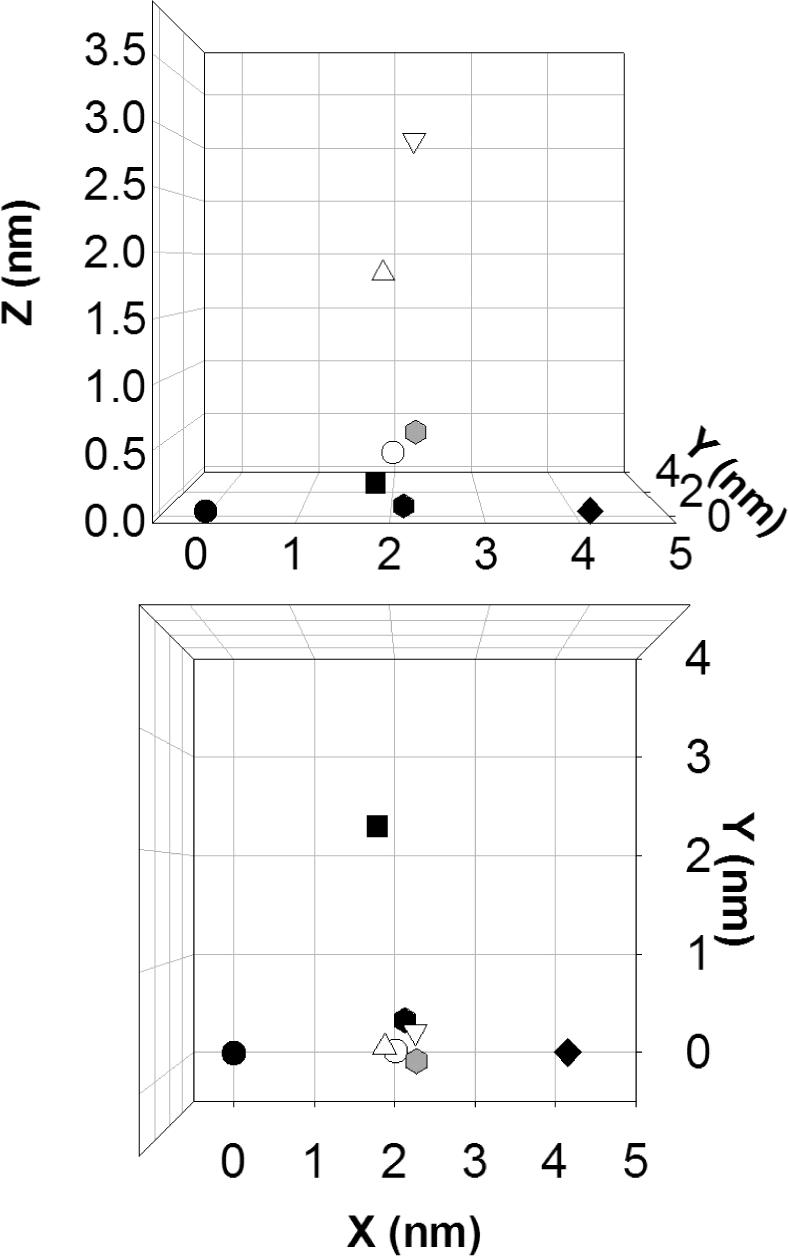

The Ton box of BtuB extends into the periplasm upon substrate binding

The distances in Table 2 were used to triangulate the position of the N-terminal end of the Ton box in the presence and absence of substrate (vitamin B12). Figure 7 shows two views of the positions of the N-terminal end of the Ton box. In this figure, the periplasmic surface of BtuB and the Cα carbons for the mutants labeled within the β-barrel lie in the x-y plane. This plane is nearly coincident with the periplasmic surface of the OM. In POPC, in the absence of substrate, the position of D6R1 (determined by the three sets of DEER data in Figure 5) is consistent with the position expected based upon the crystal structure, and the spin label is found to reside a few Angstroms into the periplasmic space. In the presence of substrate, we assume that the three sets of distances obtained for each of the three spin pairs arise from three corresponding positions for D6R1. The two longer sets of distances yield two positions that are extended from the periplasmic surface of BtuB, and place D6R1 approximately 30 Å and 20 Å into the periplasmic space. Both these positions place D6R1 directly below the hatch or core region of BtuB. A third position places D6R1 near its original (substrate free) position in POPC bilayers. This is consistent with observations obtained previously that a significant fraction of the Ton box remains folded within the barrel following substrate addition (21).

Figure 7.

A model for the position of D6 and spin labeled positions on β-barrel in the presence and absence of substrate. The x-y plane defines the periplasmic surface of BtuB, and the solid symbols show the positions of the Cα carbons of residues 157(●) , 384 (◆) and 510 (■)) in the substrate free crystal structure of BtuB (PDB ID, 1NQE). These residues lie in the x-y plane. The Cα carbon of D6  in the crystal structure in the absence of substrate lies close to the x-y plane. The shaded symbol

in the crystal structure in the absence of substrate lies close to the x-y plane. The shaded symbol  represents the position of D6R1 that is obtained by triangulation from the three experimental distances measured by DEER in the apo state of BtuB in POPC (Table 2). The open symbols represent the positions for D6R1 determined by triangulation using the distances obtained by DEER for BtuB in the presence of substrate. In Table 2, three distances are shown for each of three spin pairs. The shortest, middle, and longest sets of the three distances result in the positions for D6R1 shown by the symbols ○, △, and ▽, respectively.

represents the position of D6R1 that is obtained by triangulation from the three experimental distances measured by DEER in the apo state of BtuB in POPC (Table 2). The open symbols represent the positions for D6R1 determined by triangulation using the distances obtained by DEER for BtuB in the presence of substrate. In Table 2, three distances are shown for each of three spin pairs. The shortest, middle, and longest sets of the three distances result in the positions for D6R1 shown by the symbols ○, △, and ▽, respectively.

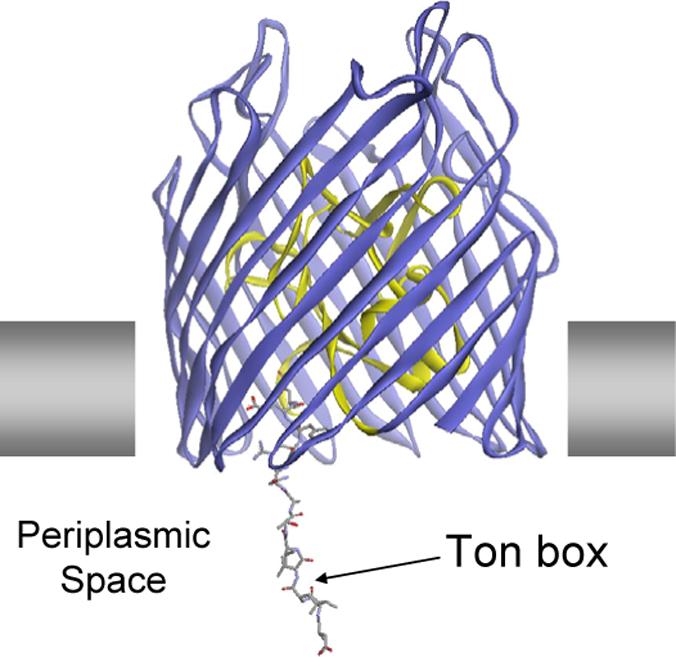

The EPR spectra reported previously for the Ton box of BtuB (9), indicate that the unfolding of the Ton box results in a loss of secondary fold and tertiary contact to approximately residue 15 on the N-terminus of BtuB. Shown in Figure 8 is a model for the substrate bound form of BtuB. This model was generated by starting with the substrate-bound crystal structure of BtuB, and unfolding the N-terminus of BtuB, including the Ton box, out to residue 15. The end of the Ton box, at position 6, was then extended to place it at a position consistent with the most extended position seen in Figure 7. The resulting structure shows that this N-terminal segment, which includes the Ton box, must be fully extended upon the addition of substrate to be consistent with the distance data.

Figure 8.

A model for the substrate bound form of BtuB. This model was generated by beginning with the substrate-bound crystal structure of BtuB (PDB ID: 1NQH) (5), and unfolding the N-terminus of BtuB, including the Ton box, out to residue 15. The N-terminus was then extended to place position 6 at a position consistent with the longest DEER distance.

Discussion

In the work presented here, pairs of spin labels were incorporated into BtuB with one label located near the periplasmic surface, and the other in the Ton box. The protein was then reconstituted into lipid bilayers composed of POPC, and a double electron-electron resonance (DEER) pulse experiment was used to measure the distances between these spin pairs. The data clearly indicate that there is a dramatic change in the position of the Ton box upon substrate addition. In particular, the end of the Ton box is positioned close to the periplasmic surface in the absence of substrate, but extends by as much as 30 Å into the periplasmic space upon substrate addition (see Figure 7). This result is consistent with CW EPR lineshapes obtained previously, which indicate that the N-terminal end of BtuB becomes unstructured from the N-terminus to approximately residue 15 in the presence of substrate (9). This extension of the Ton box into the periplasm requires that the N-terminal segment of BtuB be fully unfolded, and a model that is consistent with both the distance measurements and the results from EPR lineshapes is shown in Figure 8.

It should be noted that the models shown in Figure 7 and 8 are approximate and require the following assumptions. We assume that the distances between spins parallels the distances measured between the α-carbons in the protein and are not strongly affected by configurations of the spin label. The fact that the distances measured by EPR in the absence of substrate match reasonably well with the crystal structure, suggests that this approximation is reasonable; however, further refinement in the interpretation of these distances might be possible using energy minimization approaches as described previously (26). We also assume that the distance changes reflect changes in backbone position and not changes in the rotameric states of the label. This appears to be true, at least for labels attached to the β-barrel, which do not appear to change configuration (Figure 2). Furthermore, the distance changes we see are large, are consistent among each spin pair, and are not likely to be accounted for by changes in the rotameric state of the label. Thus, the data provide a clear indication for a significant projection of the Ton box into the periplasm upon substrate addition.

Interactions between TonB and BtuB appear to be regulated by substrate addition, and the extension of the Ton box is an ideal mechanism to regulate the interaction between BtuB and TonB (6, 15). Protein-protein interactions are often found to be mediated by conserved and highly dynamic segments of proteins (27, 28). The projection of the Ton box both makes it accessible to the periplasm, and converts it into a highly dynamic protein segment, as judged by the highly mobile EPR lineshapes that are obtained along the Ton box (9).

In the presence of substrate, the data for each mutant pair are fit well using three distances. The two longer distances correspond to the end of the Ton box being located 20 and 30 Å into the periplasm. Because of the large distance difference, these two longer distances are likely to result from two different protein backbone conformations, rather than different rotameric states of the label. In addition, dramatically different rotameric states seem unlikely, because the spin label at position 6 in these two extended configurations is not in tertiary contact, and the label should take up similar configurations relative to the backbone in each case (24). There is also a third distance component in the presence of substrate that is close to that seen in the unliganded, folded state of the Ton box. This observation is consistent with the results of CW EPR spectroscopy (21). The simplest interpretation of the DEER data is that the third distance component, which places D6R1 close to its position in the apo state, arises from the folded state of the Ton box, and that the two longer distances, where D6R1 is extends 10 and 20 Å further into the periplasm, arise from the unfolded state. The folded and unfolded conformational states are apparently in equilibrium at room temperature. This is indicated both by the results of chemical derivatization and the effects of solution osmolality on the conformational populations seen in the EPR spectra (7, 21).

In the absence of substrate, the EPR data presented here are consistent with the results of crystallography. The differences seen between the location of a spin label on residue 6, and the Cα-carbon position measured in the crystal structure (5) are within the range of distances expected due to rotameric states of the label (24). However, the crystallographic result in the presence of substrate does not show evidence for the unfolding of the Ton box, which is seen in bilayers by SDSL. As demonstrated previously, this difference results from the different conditions used for spectroscopy and for crystallography. In particular, the structural change seen by EPR is not seen by crystallography due to the high osmolality of the solutions used to produce protein crystals (11, 12). The DEER distance measurements made here are also consistent with this conclusion. The presence of PEG 3350 (a major solute used in the crystallization (29)) has a dramatic effect on the distances seen in the presence of substrate (see Figure 6C and Table 2). Under these conditions, the Ton box does not unfold, but has a position that is now consistent with that seen in the crystal structure (5). Thus, under the conditions used for crystallography, the spectroscopic and crystallographic results are in agreement.

Double resonance DEER experiments have the ability to resolve distances between spins from 15 out to 60 Å and beyond. While this length scale may be highly desirable, high concentrations of spin-labeled proteins will lead to significant intermolecular dipole-dipole interactions. This may result in a significant decay in the echo amplitude and in the DEER signal, making measurements of intramolecular interactions difficult. This sensitivity is usually not a problem for water-soluble proteins; however, membrane proteins are restricted to diffusing in a plane, and high local concentrations of protein and short intermolecular distances are more likely to be encountered. In the EPR spectra of our mutants, we found no evidence for line broadening due to intermolecular dipolar interactions; thus, the spins must be separated between proteins by distances of 20 Å or greater (23). However, the DEER measurements are sensitive to longer distances and we find clear evidence that dilution of the protein by non-labeled or wild type protein leads to a reduction in the background decay in the DEER signal (see Figure 4). We estimate that for BtuB, dilution of the labeled sample with a three-fold excess of wild type BtuB will place most intermolecular spin interactions at a distance of 80 Å or beyond, even if there is some local aggregation of BtuB in the bilayer.

In conclusion, previous work using CW EPR indicates that the Ton box of BtuB undergoes a substrate-dependent unfolding. Here we used a four-pulse DEER experiment to monitor distances between the periplasmic surface of the BtuB barrel and the end of the conserved Ton box as a function of substrate addition. The data clearly demonstrate that the Ton box projects into the periplasm upon the addition of substrate, so that the N-terminal end of the Ton box lies as much as 30 Å in the periplasm. This structural change may provide the conformation trigger that initiates protein-protein interactions between BtuB and TonB. Finally, this work demonstrates that production of a magnetically dilute protein sample, by dilution with wild-type protein, can dramatically improve the intramolecular DEER signals from spin-labeled integral membrane proteins.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Gunnar Jeschke for providing the DeerAnalysis 2006 software and for helpful comments on the analysis of the DEER data.

Abbreviations used

- AEBSF

aminoethyl-benzene sulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride

- CW

continuous wave

- DEER

double electron-electron resonance

- DTT

DL-dithiothreitol

- ELDOR

electron double resonance

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

- MTSL

methanethiosulfonate spin label

- OG

octylglucoside

- OM

outer membrane

- PEG 3350

polyethyleneglycol 3350

- POPC

palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine

- R1

spin-labeled side chain produced by derivatization of a cysteine with the MTSL

- SDSL

site-directed spin labeling

- WT

wild-type BtuB.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM 35215.

References

- 1.Ferguson AD, Hofmann E, Coulton JW, Diederichs K, Welte W. Siderophore-mediated iron transport: crystal structure of FhuA with bound lipopolysaccharide. Science. 1998;282:2215–2220. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locher KP, Rees B, Koebnik R, Mitschler A, Moulinier L, Rosenbusch JP, Moras D. Transmembrane signaling across the ligand-gate FhuA receptor: crystal structures of the free and ferrichrome-bound states reveal allosteric changes. Cell. 1998;95:771–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan SK, Smith BS, Venkatramanil L, Xia D, Esser L, Palnitkar M, Chakraborty R, van der Helm D, Deisenhofer J. Crystal structure of the outer membrane active transporter FepA from Escherichia coli. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:56–63. doi: 10.1038/4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferguson AD, Chakraborty R, Smith BS, Esser L, Van der Helm D, Deisenhofer J. Structural basis of gating by the outer membrane transporter FecA. Science. 2002;295:1715–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1067313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chimento DP, Mohanty AK, Kadner RJ, Wiener MC. Substrate-induced transmembrane signaling in the cobalamin transporter BtuB. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:394–401. doi: 10.1038/nsb914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadieux N, Kadner RJ. Site-directed disulfide bonding reveals an interaction site between energy coupling protein TonB and BtuB, the outer membrane cobalamin transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:10673–10678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadieux N, Phan PG, Cafiso DS, Kadner RJ. Differential substrate-induced signaling through the TonB-dependent transporter BtuB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10688–10693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932538100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogierman M, Braun V. Interactions between the outer membrane ferric citrate transporter FecA and TonB: studies of the FecA TonB box. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:1870–1885. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1870-1885.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanucci GE, Coggshall KA, Cadieux N, Kim M, Kadner RJ, Cafiso DS. Substrate-Induced conformational changes of the perplasmic N-terminus of an outer-membrane transporter by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1391–1400. doi: 10.1021/bi027120z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merianos HJ, Cadieux N, Lin CH, Kadner R, Cafiso DS. Substrate-induced exposure of an energy-coupling motif of a membrane transporter. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:205–209. doi: 10.1038/73309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanucci GE, Lee JY, Cafiso DS. Spectroscopic evidence that osmolytes used in crystallization buffers Inhibit a conformation change in a membrane protein. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13106–13112. doi: 10.1021/bi035439t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim M, Xu Q, Fanucci GE, Cafiso DS. Solutes Modify a Conformational Transition in a Membrane Transport Protein. Biophys. J. 2006;90:2922–2929. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pannier M, Veit S, Godt A, Jeschke G, Spiess HW. Dead-time free measurement of dipole-dipole interactions between electron spins. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;142:331–340. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeschke G. Distance measurements in the nanometer range by pulse EPR. ChemPhysChem. 2002;3:927–932. doi: 10.1002/1439-7641(20021115)3:11<927::AID-CPHC927>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coggshall KA, Cadieux N, Piedmont C, Kadner R, Cafiso DS. Transport-defective mutations alter the conformation of the energy-coupling motif of an outer membrane transporter. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13946–13971. doi: 10.1021/bi015602p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fanucci GE, Cadieux N, Piedmont CA, Kadner RJ, Cafiso DS. Structure and dynamics of the β-barrel of the membrane transporter BtuB by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11543–11551. doi: 10.1021/bi0259397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sedmak JJ, Grossberg SE. A rapid, sensitive, and versatile assay for protein using Coomassie brilliant blue G250. Anal. Biochem. 1977;79:544–552. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeschke G, Bender A, Paulsen H, Zimmermann H, Godt A. Sensitivity enhancement in pulse EPR distance measurements. J. Magn. Reson. 2004;169:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiang YW, Borbat PP, Freed JH. The determination of pair distance distributions by pulsed ESR using Tikhonov regularization. J. Magn. Reson. 2005;172:279–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fanucci GE, Cadieux N, Kadner R, Cafiso DS. Competing ligands stabilize alternate conformations of the energy coupling motif of a TonB-dependent outer membrane transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11382–11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932486100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lietzow MA, Hubbell WL. Motion of spin label side chains in cellular retinol-binding protein: correlation with structure and nearest-neighbor interactions in an antiparallel beta-sheet. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3137–3151. doi: 10.1021/bi0360962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altenbach C, Cai K, Klein-Seetharaman J, Khorana HG, Hubbell WL. Estimation of inter-residue distances in spin labeled proteins at physiological temperatures: experimental strategies and practical limitations. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15471–15482. doi: 10.1021/bi011544w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langen R, Oh KJ, Cascio D, Hubbell WL. Crystal structures of spin-labeled T4 lysozyme mutants: implications for the interpretation of EPR spectra in terms of structure. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8396–8405. doi: 10.1021/bi000604f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilger D, Jung H, Padan E, Wegener C, Vogel KP, Steinhoff HJ, Jeschke G. Assessing oligomerization of membrane proteins by four-pulse DEER: pH-dependent dimerization of NhaA Na+/H+ antiporter of E. coli. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1328–1338. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sale K, Song L, Liu YS, Perozo E, Fajer P. Explicit treatment of spin labels in modeling of distance constraints from dipolar EPR and DEER. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9334–9335. doi: 10.1021/ja051652w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunker AK, Cortese MS, Romero P, Iakoucheva LM, Uversky VN. Flexible nets. The roles of intrinsic disorder in protein interaction networks. Febs. J. 2005;272:5129–5148. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero P, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Natively disordered proteins: functions and predictions. Appl. Bioinformatics. 2004;3:105–113. doi: 10.2165/00822942-200403020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chimento DP, Mohanty AK, Kadner RJ, Wiener MC. Crystallization and initial X-ray diffraction of BtuB, the integral membrane cobalamin transporter of Escherichia coli. Acta Cryst. 2003;D59:509–511. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]