Abstract

The advent of hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance (MR) has provided new potential for the real-time visualization of in vivo metabolic processes. The aim of this work was to use hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate as a metabolic tracer to assess noninvasively the flux through the mitochondrial enzyme complex pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) in the rat heart, by measuring the production of bicarbonate (H13CO3−), a byproduct of the PDH-catalyzed conversion of [1-13C]pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. By noninvasively observing a 74% decrease in H13CO3− production in fasted rats compared with fed controls, we have demonstrated that hyperpolarized 13C MR is sensitive to physiological perturbations in PDH flux. Further, we evaluated the ability of the hyperpolarized 13C MR technique to monitor disease progression by examining PDH flux before and 5 days after streptozotocin induction of type 1 diabetes. We detected decreased H13CO3− production with the onset of diabetes that correlated with disease severity. These observations were supported by in vitro investigations of PDH activity as reported in the literature and provided evidence that flux through the PDH enzyme complex can be monitored noninvasively, in vivo, by using hyperpolarized 13C MR.

Keywords: cardiac metabolism, diabetes, fasting, DNP

Diabetes and heart failure are characterized by altered plasma substrate composition and altered substrate utilization (1, 2). The healthy heart relies on a sophisticated regulation of substrate metabolism to meet its continual energy demand. Normally, the heart derives ≈70% of its energy from oxidation of fatty acids, with the remainder primarily from pyruvate oxidation, derived from glucose (via glycolysis) and lactate. However, when plasma substrate composition is altered, the relative contributions of lipids, carbohydrates, and ketone bodies to cardiac energetics can vary substantially (1, 3). Before oxidation, all substrates are converted to acetyl-CoA, a two-carbon molecule that enters the Krebs cycle. Carbohydrate-derived pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria and irreversibly converted to acetyl-CoA by the pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme complex (PDH). Fatty acids are converted to acetyl-CoA via mitochondrial β-oxidation. Philip Randle (4) described the quantitative competition for respiration between glucose and fatty acids and the marked variation in their roles as major fuels for the heart as the glucose–fatty acid cycle.

In vivo control of the PDH enzyme complex is a fundamental determinant of the relative contributions of glucose and fatty acid oxidation to ATP production in the heart (1, 3, 5). PDH is present in the mitochondrial matrix in an active dephosphorylated form and an inactive phosphorylated form (5, 6). PDH is covalently inactivated by phosphorylation, by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK). Dephosphorylation by pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase (PDP) reactivates the enzyme. High intramitochondrial concentrations of acetyl-CoA and NADH, the end products of pyruvate, fatty acid, and ketone body oxidation, stimulate PDK, thus inactivating PDH (7). Enhanced pyruvate availability may inhibit PDK, increasing PDH activity (8). Through these direct and indirect mechanisms altered plasma substrate composition can alter the phosphorylation state and thus activity of the PDH enzyme complex (7). Elevated insulin concentrations are thought to stimulate PDP acutely, thereby dephosphorylating and activating PDH (9). The relative activities of PDK and PDP determine the proportion of PDH that is in the active dephosphorylated form.

The link between PDH regulation and disease has made the assessment of substrate selection and PDH activity important benchmarks in the study of heart disease. To date, measurement of cardiac PDH activity has been performed with invasive biochemical assays, whereas substrate selection has been monitored via radiolabeling (10–12) or carbon-13 (13C) magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy in the isolated perfused heart (13, 14). These techniques are not feasible for monitoring PDH repeatedly in the same organism, however, or for clinical diagnosis. The development of metabolic imaging with hyperpolarized MR (15, 16) has enabled unprecedented visualization of the biochemical mechanisms of normal and abnormal metabolism (17–20), making the in vivo measurement of PDH flux a possibility. In vivo, the hyperpolarized tracer [1-13C]pyruvate rapidly generates the visible metabolic products [1-13C]lactate, [1-13C]alanine, and bicarbonate (H13CO3−), which exists in equilibrium with carbon dioxide (13CO2). Because it is the PDH-mediated decarboxylation of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA that produces 13CO2, monitoring the production of hyperpolarized H13CO3− should enable a direct, noninvasive measurement of flux through the PDH enzyme complex (19), which is highly dependent on PDH activity in vivo.

The aim of this work was to demonstrate that hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate may be used as a tool for assessing flux through the PDH enzyme complex in vivo in the heart by detection of H13CO3−. We examined two well characterized rat models, overnight fasting and streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 1 diabetes, in which altered plasma metabolite composition is known to decrease glucose oxidation and modulate PDH activity by phosphorylation of the enzyme complex (21, 22). Hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate was used to assess flux through PDH qualitatively by comparing the observed H13CO3− production in control rats with H13CO3− production in fasted and diabetic rats. The alterations in PDH flux as determined with hyperpolarized 13C MR are in line with previous measurements of PDH activity in each of these conditions, made with conventional destructive methods (3, 23–26). This work has provided preliminary evidence that hyperpolarized 13C MR may be a useful technique for the noninvasive determination of metabolic fluxes in the heart.

Results

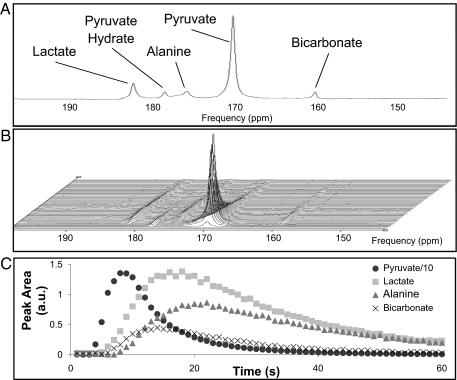

All acquired hyperpolarized 13C MR spectra were of high signal-to-noise ratio, and peaks relating to the injected [1-13C]pyruvate, as well as the metabolic products, [1-13C]lactate, [1-13C]alanine, and H13CO3−, were clearly visualized (Fig. 1). A typical series of in vivo spectra from a control fed rat are also shown in Fig. 1, along with an example time course of the variation in peak areas of each metabolic product. The arrival of pyruvate after injection was observed as a resonance at ≈170 ppm, which reached a peak 7–9 s after the onset of injection and subsequently decayed because of the loss of hyperpolarization and metabolic conversion. After a very short delay (1–3 s), the resonances attributed to hyperpolarized [1-13C]lactate, [1-13C]alanine, and H13CO3− could be observed at 183, 177, and 160 ppm, respectively. The H13CO3− peak area reached a maximum 13–15 s after injection of hyperpolarized pyruvate. The pattern of the time course data was similar across all experimental groups.

Fig. 1.

In vivo spectra from the heart of a male Wistar rat. (A) Single representative spectrum acquired at t = 10 s showing resonances attributed to the injected pyruvate (and its equilibrium product pyruvate hydrate), as well as the metabolic products, lactate, alanine, and bicarbonate. (B) Time course of spectra acquired every second over a 60-s period after injection. The arrival and subsequent decay of the injected pyruvate signal can be seen, along with the generation of lactate, alanine, and bicarbonate. (C) Example time course of the fitted peak areas of the pyruvate, lactate, alanine, and bicarbonate resonances. The pyruvate area has been reduced by a factor of 10 to improve the visualization.

The MR signals of each metabolite reached a peak as H13CO3− and [1-13C]alanine were synthesized intracellularly from the injected [1-13C]pyruvate, and the observed amounts of [1-13C]lactate (and possibly [1-13C]alanine) increased because of the reversible enzyme-mediated exchange of the 13C label. The subsequent signal decay was dominated by the relaxation of the hyperpolarized signal, although some loss can be attributed to the applied RF pulses and removal of metabolic products from the heart.

After the injection of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate, no change was observed in the heart rate of all animals [415 ± 31 beats per minute (bpm) before injection, 419 ± 31 bpm after injection], but there was a 10% increase in breathing rate (54 ± 9 bpm before injection, 60 ± 14 bpm after injection) and a 1.4% increase in body temperature (36.5 ± 0.9°C before injection, 37.0 ± 0.8°C after injection).

In the six control rats studied with hyperpolarized 13C MR, the ratio of the maximum H13CO3− peak area to the maximum [1-13C]pyruvate peak area (maximum H13CO3−:pyruvate ratio) was 0.020 ± 0.005.

Overnight Fasting.

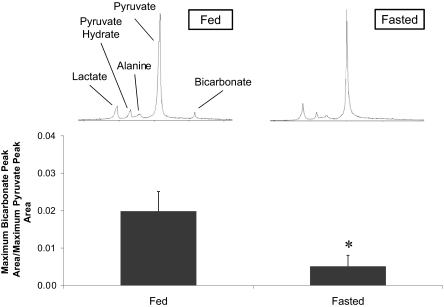

Overnight fasting resulted in a 30% decrease in plasma glucose and a 70% decrease in plasma insulin compared with the control rats, along with a 90% increase in plasma fatty acids and a 180% increase in plasma 3β-hydroxybutyrate (Table 1). After an overnight fast, the maximum H13CO3−:pyruvate ratio was 0.005 ± 0.003, a 74% decrease in H13CO3− production relative to the amount of injected pyruvate compared with control fed rats (P < 0.001). Fig. 2 illustrates this result in terms of the observed MR spectra and the quantified bicarbonate:pyruvate ratio.

Table 1.

Plasma metabolite concentrations and hyperpolarized MR results for control, fasted, and STZ diabetic rats

| Parameter | Control (n = 6) | Overnight fasted (n = 6) | Pre-STZ (n = 5) | STZ diabetic (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 210 ± 30 | 220 ± 40 | 230 ± 35 | 217 ± 40* |

| Glucose, mmol/liter | 11 ± 2 | 8 ± 2† | 21 ± 4‡ | |

| Insulin, μg/liter | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 0.1† | 0.5 ± 0.3 | |

| NEFA, mmol/liter | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1† | 0.3 ± 0.1 | |

| BHB, mmol/liter | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.7† | 0.6 ± 0.6 | |

| H13CO3−/pyruvate | 0.020 ± 0.005 | 0.005 ± 0.003§ | 0.026 ± 0.002 | 0.009 ± 0.007¶ |

Values are means ± SD. STZ, streptozotocin; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acid; BHB, 3β-hydroxybutyrate. Pre-STZ blood was not analyzed for metabolite composition.

Significant difference from control rats: †, P < 0.05,

‡, P < 0.005, and

§, P < 0.001.

Significant difference from paired pre-STZ rats: *, P < 0.05,

¶, P < 0.02.

Fig. 2.

Bicarbonate:pyruvate ratio in fed rats compared with fasted rats (n = 6; *, P < 0.001). Representative single spectra, acquired at t = 10 s, illustrate the difference in bicarbonate production.

STZ-Induced Diabetes.

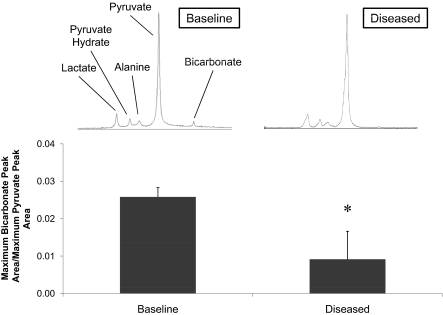

At baseline, the six healthy rats had a maximum H13CO3−:pyruvate ratio of 0.026 ± 0.002. Injection with STZ led to a 90% increase in plasma glucose after 5 days in five of the six rats injected with STZ, compared with control rats from the overnight fasting study. This finding indicated that these five rats were in the early diabetic state. Body weights were significantly lower 5 days after STZ injection, dropping 13 ± 10 g, although insulin, plasma free fatty acid, and 3β-hydroxybutyrate levels did not significantly change (Table 1). In the five diabetic rats, hyperpolarized 13C MR revealed a maximum H13CO3−:pyruvate ratio of 0.009 ± 0.007. This represented a 65% reduction in the production of H13CO3− relative to the injected pyruvate after STZ injection compared with rats pre-STZ injection (Fig. 3, P < 0.02).

Fig. 3.

Bicarbonate:pyruvate ratio in rats before and 5 days after induction of type 1 diabetes with STZ injection (n = 5; *, P < 0.02). Representative single spectra, acquired at t = 10 s, illustrate the difference in bicarbonate production.

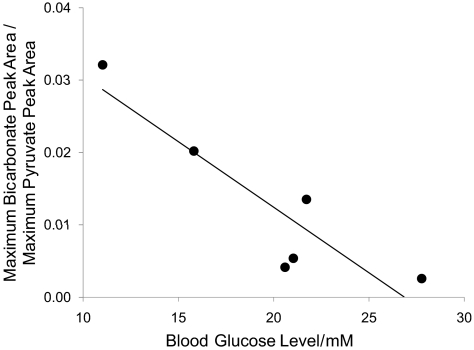

Further, in all six rats, bicarbonate production correlated negatively with the severity of STZ-induced type 1 diabetes, as qualitatively indicated by the extent of blood glucose elevation. Fig. 4 depicts the correlation between bicarbonate production and blood glucose. In the rats that were affected to a lesser extent by the STZ injection and had either normal or only slightly elevated blood glucose, bicarbonate production remained high; the more severely diabetic rats with very high blood glucose showed depressed bicarbonate production.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between blood glucose and bicarbonate:pyruvate ratio in six rats, 5 days after induction of type 1 diabetes with STZ (r = −0.93). In rats with the highest blood glucose, the increased severity of the disease further inhibited PDH-mediated bicarbonate production.

Discussion

Use of hyperpolarized 13C MR revealed substantial differences in the in vivo cardiac pyruvate metabolism of normal fed rats, rats starved for an excess of 14 h, and rats before and after type 1 diabetes had been induced. Fasted rats showed a virtual depletion of H13CO3− production, whereas rats injected with STZ showed a reduction in H13CO3− production in direct proportion to the severity of their disease. These results depicted the reduction in PDH-mediated pyruvate decarboxylation and Krebs cycle uptake as a result of physiological adaptation to starvation and maladaptation caused by type 1 diabetes. Hyperpolarized 13C MR noninvasively detected the changes in PDH flux with high sensitivity, showing significant differences between normal rats and altered metabolic states with low experimental numbers and little variability within each group. This work indicated that hyperpolarized 13C MR reliably recognizes changes in metabolism caused by both physiological and pathological perturbations. Further, in combination with a previous study of local hyperpolarized H13CO3− production after myocardial ischemia (27), this investigation of STZ-induced diabetes indicates the potential utility of hyperpolarized 13C MR in clinical diagnosis of heart disease.

Extensive ex vivo and in vitro studies of cardiac metabolism in fasted and diabetic rats have shown profound changes in substrate selection and PDH activity, characteristic of these conditions. In both starvation and STZ-induced diabetes, the heart switches almost exclusively to use of fatty acids and ketone bodies for its ATP requirements (1, 2, 7, 22, 24) at the expense of glucose and pyruvate oxidation. This switch in substrate utilization is dominated by decreased PDH activity, concomitant with increased PDK expression (28) and decreased PDP expression (29). A decrease in percentage cardiac PDH activity of between 70 and 95% has been measured in vitro and reported in rats after 4–24 h of starvation (3, 23, 24), whereas a decrease of between 50 and 80% has been measured in vitro in experimentally induced diabetes (3, 24–26). Our results, based on measurement of H13CO3− production, detected a decrease in in vivo PDH flux of 74% in fasted rats and 65% in diabetic rats, values that were of the same magnitude as in vitro data describing PDH activity in rats under the same conditions (3, 23–26). The agreement between our results and literature values provides evidence that the qualitative measurement of H13CO3− production with hyperpolarized 13C MR does accurately portray flux through PDH and suggests that activity of the PDH enzyme complex may be the dominant influence on the reduction of PDH flux in starvation and diabetes observed in this work. Further, the link between disordered substrate selection in heart disease and the chronic regulation of PDH activity suggests that the technique used here may be invaluable in the clinical management of diabetes and other forms of heart disease, in terms of early detection, monitoring of disease severity and risk assessment, and in development of novel metabolic treatments.

The cardiac spectra reported in this work were localized with a surface coil placed over the chest. It is certain that contamination from neighboring organs, notably blood, liver, and skeletal muscle, contributed to our results, especially in the detection of [1-13C]lactate and [1-13C]alanine. However, we are confident that the [1-13C]pyruvate to H13CO3− metabolism described here was dominated specifically by cardiac metabolism, based both on the metabolic time course of H13CO3− (Fig. 1) and the high metabolic turnover of the heart. After pyruvate administration into the tail vein, it would have traveled directly to the heart for its earliest metabolism, reaching other organs, including skeletal muscle and the liver, at a later time point. The time course of bicarbonate production closely followed the time course of injected pyruvate in that the initial detection and accumulation of H13CO3− occurred within 1–3 s of pyruvate arrival in the chest. It seems unlikely that H13CO3− produced anywhere outside the heart would appear so rapidly after cardiac pyruvate delivery. Further, the extremely high rate of PDH and Krebs cycle flux in the heart (19) compared with liver (30, 31) and resting skeletal muscle (32, 33) and low concentration of the PDH enzyme complex in the constituents of blood, notably white blood cells and platelets (34), provide further evidence that the bicarbonate measurements in this work reflected local cardiac metabolism and that any contribution to H13CO3− signal from neighboring organs was negligible.

This work has demonstrated the potential for hyperpolarized 13C MR to follow metabolic pathway fluxes, noninvasively and in vivo. However, to extract quantitative kinetic information from hyperpolarized 13C MR experiments, a better understanding of the interaction between the injected hyperpolarized tracer and the physiological system is necessary. Parameters including the in vivo nuclear T1 relaxation time of pyruvate and its metabolites, the effect of RF pulsing, and the plasma and intracellular concentrations of injected pyruvate must be determined to enable quantitative in vivo measurement of PDH flux.

Supraphysiogical levels of pyruvate may cause functionally important intracellular pH changes (35) because a proton is transported into cells concurrently with each molecule of pyruvate (36) as well as shifting the plasma pH and redox potential (37), effects that fundamentally influence quantitative tracking of pyruvate metabolism. The hyperpolarized 13C MR protocol used in this work had the major advantage that all data reported were acquired within 30 s of injection, and thus acquisition likely preempted any physiological changes induced by supraphysiological levels of pyruvate. In this work, we observed no change in heart rate after injection of hyperpolarized pyruvate, but we did observe a small increase in breathing rate and temperature.† The small measured change in breathing rate and any possible changes in pH and blood pressure (parameters not measured) should not have altered cardiac metabolism within the first 30 s after pyruvate injection and should therefore not have affected our measurements. Further, elevated mitochondrial pyruvate concentration has been demonstrated to enhance PDH activity within several minutes (8, 38). In the subminute time frame of this hyperpolarized MR experiment, however, the only effect expected was the provision of additional PDH substrate compared with the products, acetyl-CoA, NADH, and CO2.

Although ex vivo and in vitro studies of cardiac disease have demonstrated that changes in substrate selection do take place, they are limited, in that most studies generate steady-state, rather than real-time, information. Low metabolite concentrations imply that radioisotope and MR spectroscopy studies of cardiac metabolism require long periods of time to build up detectable levels of signal, on the order of several minutes. However, the advent of hyperpolarized 13C MR, in which 13C signal is amplified by >10,000-fold, has made real-time visualization of substrate uptake and metabolism possible. The potential to measure instantaneous transporter affinity for a given metabolic tracer and the rate of its enzymatic conversion to other species may enable us to elucidate subtle mechanistic changes that cause altered substrate selection. Further, traditional ex vivo (10, 11, 14, 25) and in vitro (23, 24, 26) studies of metabolism are inherently destructive methods, relying on terminal experiments that prevent investigation of disease progression. Our use of hyperpolarized 13C MR to study STZ-induced diabetes has demonstrated the ability of this technique to examine living animals serially throughout the course of a disease. Monitoring real-time metabolism throughout various stages of a particular disease may enhance general understanding of the cause of the disease, its advancement in severity, and its response to therapy.

Materials and Methods

The [1-13C]pyruvate was obtained from GE Healthcare. The trityl radical and 3-Gd gadolinium complex were supplied by GE Healthcare under a research agreement and may be difficult to obtain. All rats were housed on a 12:12-h light–dark cycle (lights on 7 a.m. and lights off at 7 p.m.) in animal facilities at the University of Oxford. All animal studies were performed between 8 a.m. and 3 p.m., during their early absorptive (fed) state, unless otherwise indicated. All investigations conformed to Home Office Guidance on the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (HMSO) of 1986 and to institutional guidelines.

Overnight Fasting.

Two groups of six male Wistar rats (200–250 g) were each examined with hyperpolarized 13C MR, as described below. One group was fasted overnight before the examination, with food removed at 1800 h on the day before the experiment. This corresponded with fasting for >14 h from the time food was removed. The second control group was examined in the fed state, with food and water available ad libitum. Following the hyperpolarized 13C MR protocol, rats were recovered from anesthesia and sacrificed for measurement of plasma metabolites.

STZ-Induced Diabetes.

Six male Wistar rats (200–275 g) were initially examined via the hyperpolarized 13C MR protocol, such that each rat could serve as its own experimental control. Type 1 diabetes was subsequently induced with a single i.p. injection of freshly prepared STZ (50 mg/kg body weight) in 50 mM cold citrate buffer (pH 4.5). Five days after STZ diabetes induction, rats were again examined with the hyperpolarized 13C MR protocol. Rats were then recovered and sacrificed for measurement of post-STZ plasma metabolites, to confirm diabetic status.

Pyruvate Polarization and Dissolution.

Approximately 40 mg of [1-13C]pyruvic acid, doped with 15 mM trityl radical and 0.8 μl of 3-Gd (14.6 mM), was hyperpolarized in a polarizer, with 45 min of microwave irradiation as described in ref. 15. The sample was subsequently dissolved in a pressurized and heated alkaline solution, containing 100 mg/liter EDTA, to yield a solution of 80 mM hyperpolarized sodium [1-13C]pyruvate with a polarization of ≈30% and physiological temperature and pH (17).

Animal Handling.

Isofluorane anesthesia was used for induction at 2.5% in oxygen, and body temperature was monitored and maintained at 37°C. A catheter was introduced into the tail vein for i.v. administration of the hyperpolarized solution, and rats were then placed in a home-built animal-handling system.‡ ECG, respiration rate, and body temperature were monitored throughout the experiment, and air heating was provided. These parameters were recorded 5 min before pyruvate injection and ≈1 min after pyruvate injection. Anesthesia was maintained by means of 1.7% isofluorane delivered to, and scavenged from, a nose cone during the experiment, followed by full recovery.

Hyperpolarized 13C MR Protocol.

A home-built 1H/13C butterfly coil (loop diameter, 2 cm) was placed over the rat chest, localizing signal from the heart. Rats were positioned in a 7 T horizontal bore MR scanner interfaced to an Inova console (Varian Medical Systems). Correct positioning was confirmed by the acquisition of an axial proton FLASH image (TE/TR, 1.17/2.33 ms; matrix size, 64 × 64; FOV, 60 × 60 mm; slice thickness, 2.5 mm; excitation flip angle, 15°). An ECG-gated shim was used to reduce the proton linewidth to ≈120 Hz.

Immediately before injection, an ECG-gated 13C MR pulse-acquire spectroscopy sequence was initiated. One milliliter of hyperpolarized pyruvate was injected over 10 s into the anesthetized rat. Sixty individual cardiac spectra were acquired over 1 min after injection (TR, 1 s; excitation flip angle, 5°; sweep width, 6,000 Hz; acquired points, 2,048; frequency centered on the pyruvate resonance).

Plasma Metabolites.

One hour after recovery from anesthesia, rats were killed by exsanguination after a 1-ml injection (i.p.) of pentobarbitone sodium. Approximately 3 ml of blood was drawn from the chest cavity after the heart was excised. Blood was immediately centrifuged (1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), and plasma was removed. A 200-μl aliquot of plasma was separated, and the lipoprotein lipase inhibitor tetrahydrolipostatin was added for nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) analysis. All plasma samples were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C. An ABX Pentra 400 (Horiba ABX Diagnostics) was used to perform assays for plasma glucose, NEFAs (Wako Diagnostics) and 3β-hydroxybutyrate (Randox Co.). Plasma insulin was measured by using a rat insulin ELISA (Mercodia).

MR Data Analysis.

Cardiac 13C MR spectra were analyzed by using the AMARES algorithm as implemented in the jMRUI software package (39). Spectra were baseline and DC offset-corrected based on the last half of acquired points. Peaks corresponding with pyruvate and its metabolic derivatives lactate, alanine, and bicarbonate were fitted with prior knowledge assuming a Lorentzian line shape, peak frequencies, relative phases, and linewidths. Quantified peak areas were plotted against time in Excel (Microsoft). The maximum peak area of each metabolite over the 60 s of acquisition was determined for each series of spectra. Relative H13CO3− production was calculated as a ratio of H13CO3−:pyruvate by dividing the maximum H13CO3− peak area by the maximum pyruvate peak area. The maximum pyruvate and H13CO3− peak areas were not necessarily at the same time point and were determined solely by their magnitude. This normalized any variations between datasets in polarization, pyruvate concentration after dissolution, and pyruvate injection volume and rate, thus providing a measure of H13CO3− based on the pyruvate delivery in each particular experiment.

Statistical Analysis.

Values reported are means ± SD. Statistical significance between the control and fasted groups, and between the control and diabetic groups, were assessed by using a two-sample t test assuming unequal variances. Significant differences in MR data before and after STZ injection were assessed by using a paired two-sample t test for means. Statistical significance was considered at the P < 0.05 level.

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Sebastien Serres and Emma Carter for their technical assistance. This work was supported by Medical Research Council Grant G0601490, British Heart Foundation Grant PG/07/070/23365, and by GE Healthcare. M.A.S. was supported by a Newton Abraham Scholarship Foundation Ph.D. studentship.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Grant funding from GE Healthcare.

The observed change in temperature is attributed to the feedback-controlled heating system employed in our animal handling system and not to any effects from the injected pyruvate.

Cassidy PJ, et al., Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2005, Miami, FL, May 7–13.

References

- 1.Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1093–1129. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taegtmeyer H, McNulty P, Young ME. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in diabetes. I. General concepts. Circulation. 2002;105:1727–1733. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012466.50373.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randle PJ. Fuel selection in animals. Biochem Soc Trans. 1986;14:799–806. doi: 10.1042/bst0140799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Randle PJ, Garland PB, Hales CN, Newsholme EA. The glucose fatty-acid cycle: Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1963;1:785–789. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)91500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed LJ. Regulation of mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by a phosphorylation–dephosphorylation cycle. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1981;18:95–106. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152818-8.50012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linn TC, Pettit FH, Reed LJ. α-Keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. X. Regulation of the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from beef kidney mitochondria by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1969;62:234–241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper RH, Randle PJ, Denton RM. Stimulation of phosphorylation and inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase by physiological inhibitors of the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction. Nature. 1975;257:808–809. doi: 10.1038/257808a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pratt ML, Roche TE. Mechanism of pyruvate inhibition of kidney pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase and synergistic inhibition by pyruvate and ADP. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:7191–7196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caruso M, et al. Activation and mitochondrial translocation of protein kinase Cδ are necessary for insulin stimulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in muscle and liver cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45088–45097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopaschuk GD, Barr RL. Measurements of fatty acid and carbohydrate metabolism in the isolated working rat heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;172:137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allard MF, et al. Preischemic glycogen reduction or glycolytic inhibition improves postischemic recovery of hypertrophied rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H66–H74. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.1.H66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.el Alaoui-Talibi Z, Landormy S, Loireau A, Moravec J. Fatty acid oxidation and mechanical performance of volume-overloaded rat hearts. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H1068–H1074. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.4.H1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey IA, Gadian DG, Matthews PM, Radda GK, Seeley PJ. Studies of metabolism in the isolated, perfused rat heart using 13C NMR. FEBS Lett. 1981;123:315–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FM. Carbon flux through citric acid cycle pathways in perfused heart by 13C NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1987;212:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, et al. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of over 10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golman K, in 't Zandt R, Thaning M. Real-time metabolic imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11270–11275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601319103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golman K, Zandt RI, Lerche M, Pehrson R, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. Metabolic imaging by hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance imaging for in vivo tumor diagnosis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10855–10860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day SE, et al. Detecting tumor response to treatment using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Nat Med. 2007;13:1382–1387. doi: 10.1038/nm1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merritt ME, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C allows a direct measure of flux through a single enzyme-catalyzed step by NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19773–19777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706235104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen AP, et al. Hyperpolarized C-13 spectroscopic imaging of the TRAMP mouse at 3T-Initial experience. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1099–1106. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panagia M, Gibbons GF, Radda GK, Clarke K. PPAR-α activation required for decreased glucose uptake and increased susceptibility to injury during ischemia. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:H2677–H2683. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00200.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerbey AL, et al. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase in rat heart. Mechanism of regulation of proportions of dephosphorylated and phosphorylated enzyme by oxidation of fatty acids and ketone bodies and of effects of diabetes: Role of coenzyme A, acetyl-coenzyme A and reduced and oxidized nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide. Biochem J. 1976;154:327–348. doi: 10.1042/bj1540327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holness MJ, Sugden MC. Pyruvate dehydrogenase activities during the fed-to-starved transition and on refeeding after acute or prolonged starvation. Biochem J. 1989;258:529–533. doi: 10.1042/bj2580529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wieland O, Siess E, Schulze-Wethmar FH, von Funcke HG, Winton B. Active and inactive forms of pyruvate dehydrogenase in rat heart and kidney: Effect of diabetes, fasting, and refeeding on pyruvate dehydrogenase interconversion. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1971;143:593–601. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatham JC, Forder JR. Relationship between cardiac function and substrate oxidation in hearts of diabetic rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H52–H58. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seymour AM, Chatham JC. The effects of hypertrophy and diabetes on cardiac pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2771–2778. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golman K, Petersson JS. Metabolic imaging and other applications of hyperpolarized 13C1. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:932–942. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu P, et al. Starvation and diabetes increase the amount of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzyme 4 in rat heart. Biochem J. 1998;329:197–201. doi: 10.1042/bj3290197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang B, Wu P, Popov KM, Harris RA. Starvation and diabetes reduce the amount of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase in rat heart and kidney. Diabetes. 2003;52:1371–1376. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.6.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones JG, Solomon MA, Cole SM, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. An integrated 2H and 13C NMR study of gluconeogenesis and TCA cycle flux in humans. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:E848–E856. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.4.E848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jucker BM, Lee JY, Shulman RG. In Vivo 13C NMR measurements of hepatocellular tricarboxylic acid cycle flux. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12187–12194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibala MJ, MacLean DA, Graham TE, Saltin B. Tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediate pool size and estimated cycle flux in human muscle during exercise. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E235–E242. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.2.E235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jucker BM, Rennings AJ, Cline GW, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. In vivo NMR investigation of intramuscular glucose metabolism in conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E139–E148. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.1.E139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blass JP, Cederbaum SD, Kark RA. Rapid diagnosis of pyruvate and ketoglutarate dehydrogenase deficiencies in platelet-enriched preparations from blood. Clin Chim Acta. 1977;75:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(77)90496-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermann HP, Zeitz O, Keweloh B, Hasenfuss G, Janssen PM. Pyruvate potentiates inotropic effects of isoproterenol and Ca2+ in rabbit cardiac muscle preparations. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:H702–H708. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halestrap AP. The mitochondrial pyruvate carrier: Kinetics and specificity for substrates and inhibitors. Biochem J. 1975;148:85–96. doi: 10.1042/bj1480085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholz TD, Laughlin MR, Balaban RS, Kupriyanov VV, Heineman FW. Effect of substrate on mitochondrial NADH, cytosolic redox state, and phosphorylated compounds in isolated hearts. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H82–H91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.1.H82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.St Amand TA, Spriet LL, Jones NL, Heigenhauser GJ. Pyruvate overrides inhibition of PDH during exercise after a low-carbohydrate diet. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:E275–E283. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.2.E275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naressi A, Couturier C, Castang I, de Beer R, Graveron-Demilly D. Java-based graphical user interface for MRUI, a software package for quantitation of in vivo/medical magnetic resonance spectroscopy signals. Comput Biol Med. 2001;31:269–286. doi: 10.1016/s0010-4825(01)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]