Abstract

Previous pathway engineering work demonstrated that the desosamine biosynthetic pathway in Streptomyces venezuelae could be converted to an efficient mycaminose biosynthesizing pathway by replacement of DesI with the hexose 3,4-ketoisomerase Tyl1a. In this work, FdtA, a ketoisomerase homologous to Tyl1a which catalyzes conversion of the Tyl1a substrate to the C-4 epimer of the Tyl1a product was used to replace DesI. The ability of desosamine pathway enzymes DesV, DesVI, DesVII, and DesVIII to accept substrates with inverted C-4 stereochemistry in the mutant expressing FdtA resulted in formation of macrolide derivatives bearing 4-epi-D-mycaminose, a sugar heretofore unobserved in Nature. Interestingly, minor glycosylated macrolides bearing another non-natural sugar, 3-N-monomethylamino-3-deoxy-D-fucose, were also produced by this mutant. An explanation for the formation of these unexpected new compounds is presented, and the implications of this work for combinatorial biosynthesis of new antibiotics are discussed.

A growing appreciation of the essentiality of deoxysugars for the physiological functions of cell surface polysaccharides1 and the biological activities of many secondary metabolites2 has led to a surge of investigations of the biosynthesis of deoxysugars.3 These studies have facilitated the rational manipulation of the deoxysugar biosynthetic machinery to generate a diverse array of new glycoconjugates with potential clinical applications. The success of these engineering strategies hinges on the identification and exploitation of the substrate flexibilities of pathway enzymes. Interestingly, the substrate flexibilities of several natural product glycosyltransferases have been demonstrated and subsequently exploited for the biosynthesis of a variety of natural product glycoforms.4 Recent in vitro and in vivo investigations of unusual sugar biosynthesis and work on construction of hybrid deoxysugar biosynthetic pathways in engineered hosts suggests that relaxed substrate specificity is a general trait among secondary metabolite sugar biosynthetic enzymes.4–5 Hence, we envisioned taking advantage of the substrate flexibility of deoxysugar biosynthetic enzymes to assemble pathways for the construction of sugar structures that have not yet been found in nature, thus increasing the diversity of sugar donors available for natural product glycodiversification. Herein we report an example of an engineered biosynthetic pathway which yielded non-natural sugar-bearing macrolide derivatives in vivo.

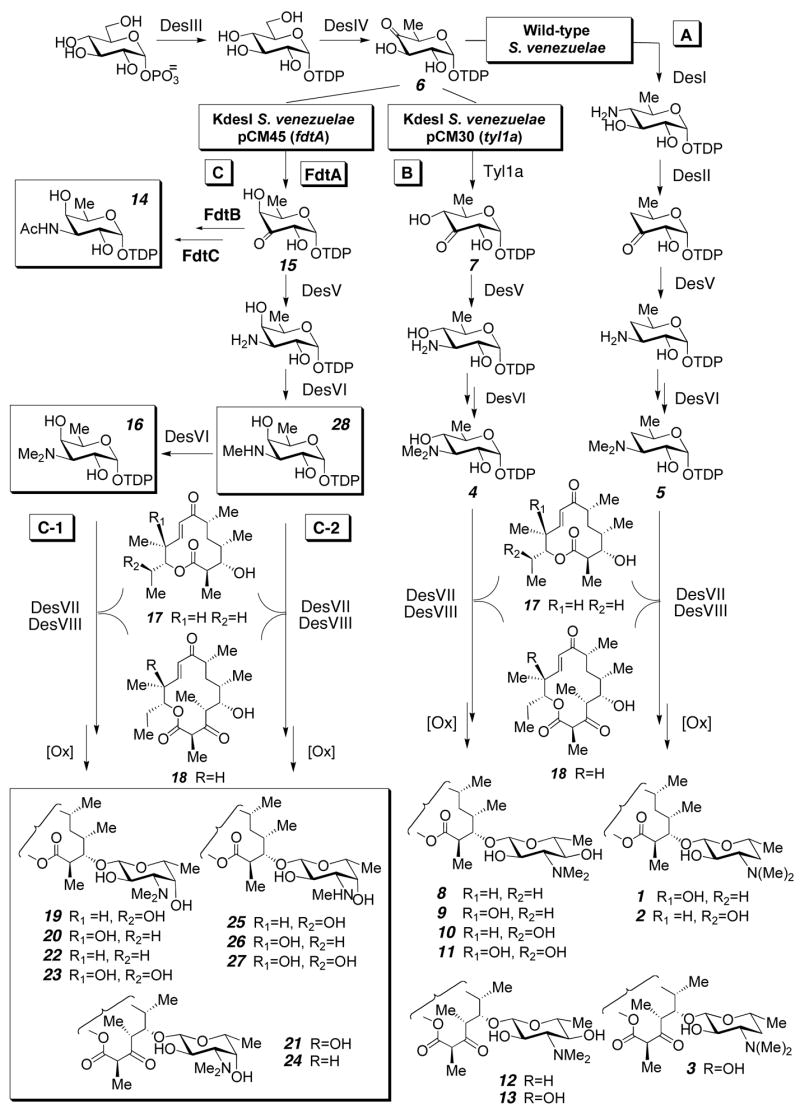

Macrolide antibiotics, such as methymycin (1), neomethymycin (2), and pikromycin (3) produced by Streptomyces venezuelae (Figure 1, path A) comprise an important class of compounds, many of which are effective antibacterial agents. As part of our efforts to alter the glycosylation patterns of macrolide antibiotics, we have successfully carried out manipulation of the well-characterized TDP-D-mycaminose (4) and TDP-D-desosamine (5) biosynthetic pathways to generate methymycin/pikromycin analogues with altered sugar structures.6 We have also found that replacement of DesI, the C-4 aminotransferase which acts on TDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-D-glucose (6) in the desosamine pathway, with Tyl1a, which converts 6 to TDP-3-keto-6-deoxy-D-glucose (7), switches the desosamine pathway to an efficient mycaminose biosynthesis pathway,6a producing mycaminosylated macrolide derivatives 8–13 in the resulting S. venezuelae mutant (Figure 1, path B). FdtA, a TDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-D-glucose 3,4-ketoisomerase involved in the biosynthesis of 3-N-acetyl-3-deoxy- D-fucose (14), a precursor of the S-layer polysaccharides in Aneurinibacillus thermoaerophilus, shows moderate sequence identity with Tyl1a (33% identity),7 and like Tyl1a uses 6 as the substrate, yet forms the C-4 epimer of the Tyl1a product, TDP-3-keto-D-fucose (15). The stereochemical divergence of these two related enzyme-catalyzed reactions offered a unique opportunity to convert our engineered D-mycaminose biosynthetic pathway into a system making the non-naturally occurring TDP-4-epi-D-mycaminose (16) by the replacement of Tyl1a with FdtA (Figure 1, path C). The product 16 may serve as the sugar donor for glycosyltransfer of 4-epi-D-mycaminose to the endogenous aglycones 10-deoxymethynolide (17) and narbonolide (18) (Figure 1, path C-1). The success of this endeavor depends both on the efficient expression of FdtA encoded by highly AT-rich A. thermoaerophilus DNA in the high-GC Gram-positive S. venezuelae, and on the ability of the desosamine biosynthetic enzymes DesV, DesVI, DesVII, and DesVIII to process substrates with an axial C-4 hydroxyl group.

Figure 1.

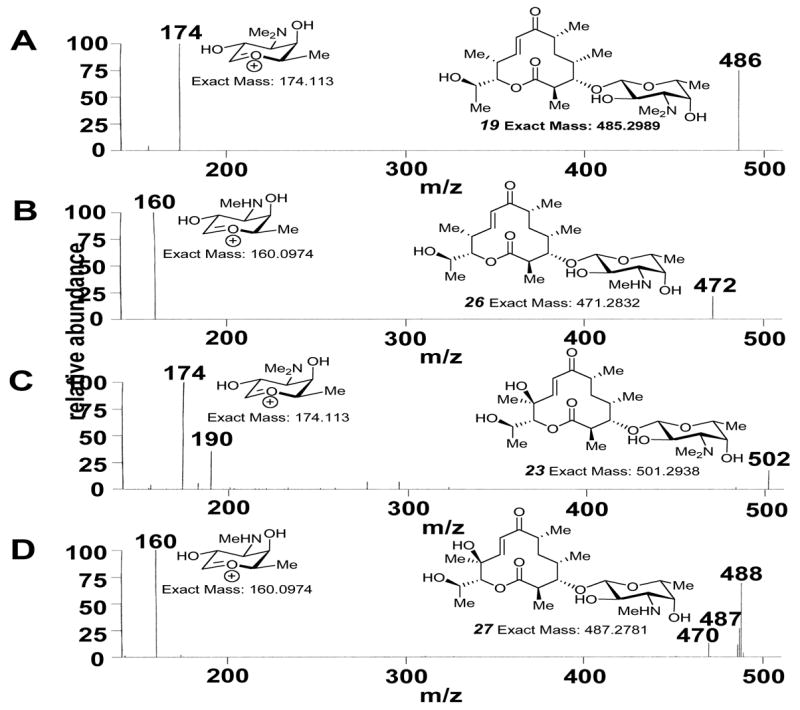

Confirmation of the identity of the deoxysugar 3-N-monomethyl-3-deoxy-D-fucose in 26 (B) and 27 (D) by comparison of positive mode ESI-MS-MS fragmentation patterns of the parent peaks of 26 and 27 to those of 19 (A) and 23 (C), respectively.

In order to construct this pathway, fdtA was amplified by colony PCR from A. thermoaerophilus with an engineered ribosome binding site and cloned into the S. venezuelae expression vector pCM1d.8 The resulting construct, pCM45, was expressed in the KdesI mutant of S. venezuelae.8 TLC analysis of small scale chloroform extracts of this mutant revealed several new polar spots with Rf values indicative of glycosylated macrolide products. Subsequently, a large-scale culture (3L) of the KdesI/pCM45 mutant was grown in vegetative media under previously reported standard conditions8 to obtain more of the new compounds. Separation of the crude extracts by silica gel chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH) and analysis of the resulting fractions by 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed the presence of three major glycosylated compounds. Interestingly, seven additional minor glycosylated macrolide species were also discernible. Together, these glycosylated compounds accounted for about 55% of the total macrolide produced.9 Further separation by silica gel chromatography and reverse-phase HPLC8 allowed purification of one of the three major compounds, which was structurally characterized by 1H, 13C, COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and NOESY NMR spectroscopies and high resolution CI+-MS, unambiguously identifying it as the non-natural sugar-bearing macrolide 4-epi-D-mycaminosyl neomethynolide (19).8 The other two major compounds were identified by 1H NMR spectroscopy and high resolution CI+-MS as 4-epi-D-mycaminosyl methynolide (20) and 4-epi-D-mycaminosyl pikronolide (21).8

Six of the remaining minor compounds were purified and characterized by high resolution CI+-MS. Three were found to have masses and polarities consistent with 4-epi-D-mycaminosyl 10-deoxymethynolide (22), 4-epi-D-mycaminosyl novamethynolide (23), and 4-epi-D-mycaminosyl narbonolide (24). Surprisingly, the other three compounds displayed masses consistent with desmethyl analogues of 19/20, and 23. Reasoning that these compounds could bear 3-N-monomethylated sugars, ESI-MS-MS fragmentation analysis was carried out on the purified desmethyl analogues of 19 and 23 to determine whether the aglycone or the sugar lacked a methyl group. Comparison of the ESI-MS-MS fragmentation patterns of 19 and 23 (Figure 1A, C, respectively) and their corresponding desmethyl analogues (Figure 1B, D, respectively) clearly showed that the sugar moiety of each of these analogues lacks a methyl group. These results strongly suggest that these analogues are new 3-N-monomethyl-3-deoxy-D-fucosyl derivatives of neomethynolide/methynolide (25/26) and novamethynolide (27, Scheme 1). The presence of these compounds was unexpected, as no macrolides bearing 3-N-monomethylated derivatives of desosamine or mycaminose have ever been detected in the wild-type or engineered S. venezuelae strains. The production of these compounds by the KdesI/pCM45 mutant likely results from the interception of aportion of TDP-3-N-monomethyl-3-deoxy-D-fucose (28), the product of the first DesVI-catalyzed methyltransfer reaction, by the glycosyl-transferase DesVn (Scheme 1, path C-2) before it can be converted to TDP-4-epi-D-mycaminose (16) by DesVI. A plausible explanation for this phenomenon is that the kinetics of the second DesVI-catalyzed methylation step might be slowed due to the change in substrate C-4 configuration, allowing sufficient accumulation of 28 for DesVII to couple it to 10-deoxymethynolide (17), leading to the formation of 25/26 and 27.

Scheme 1.

These results are significant for three reasons. First, they demonstrate the feasibility of designing and assembling a pathway for the biosynthesis and attachment of a non-natural deoxysugar, TDP-4-epi-D-mycaminose (16), resulting in the new macrolides 19–24. Second, the ability of four desosamine pathway enzymes, DesV, DesVI, DesVII, and DesVIII to tolerate substrates with altered C-4 stereochemistry was revealed and was crucial for a successful outcome. Third, this engineering work serendipitously led to the creation of three additional new macrolide derivatives (25–27) bearing the non-natural sugar, 3-N-monomethyl-3-deoxy-D-fucose. Formation of 25–27 relied on subtle differences in the proficiencies of two desosamine pathway enzymes, DesVI and DesVII, for turnover of non-natural substrates. These differences were only brought to light after interrogation of these enzymes with non-natural substrates generated by pathway engineering, highlighting the potential of exploiting the influence of subtle enzymological effects on the outcome of engineered pathways.

With the increasingly rapid discovery of sugar pathway-encoding genes in both natural product and polysaccharide biosynthesis, more new components for pathway construction are becoming available to the biosynthetic engineer. These new “glycosyl tools” expand the number of feasibly constructed sugar structures, making it possible to assemble pathways to make sugars that do not exist in nature, such as 16 and 28. The nine non-natural sugar-bearing compounds (19–27) generated in this work demonstrate the feasibility of using this approach to generate non-natural sugar-bearing secondary metabolites. Efforts are underway to fully exploit the potential of such a combinatorial biosynthesis strategy.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul Messner at the University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria for his generous gift of the A. thermoaerophilus cell stock and Drs. Mehdi Moini and Yasushi Ogasawara for valuable discussions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM35906 and GM54346.

References

- 1.(a) Schnaitman CA, Klena JD. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:655–682. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.655-682.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Samuel G, Reeves P. Carb Res. 2003;338:2503–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Weymouth-Wilson AC. Nat Prod Rep. 1997;14:99–110. doi: 10.1039/np9971400099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thorson JS, Hosted TJ, Jr, Jiang J, Biggins JB, Ahlert J. Curr Org Chem. 2001;5:139–167. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kren V, Martinkova L. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:1303–1328. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) He XM, Liu H-w. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:701–754. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Trefzer A, Salas JA, Bechthold A. Nat Prod Rep. 1999;16:283–299. doi: 10.1039/a804431g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hallis TM, Liu H-w. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:579–588. [Google Scholar]; (c) He X, Agnihotri G, Liu H-w. Chem Rev. 2000;100:4615–4661. doi: 10.1021/cr9902998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Salas JA, Mendez C. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;9:77–85. doi: 10.1159/000088838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Blanchard S, Thorson JS. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Borisova SA, Zhang C, Takahashi H, Zhang H, Wong AW, Thorson JS, Liu H-w. Ang Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2748–2753. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Zhao Z, Hong L, Liu H-w. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7692–7693. doi: 10.1021/ja042702k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Takahashi H, Liu Y-n, Chen H, Liu H-w. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9340–9341. doi: 10.1021/ja051409x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Perez M, Lombo F, Zhu L, Gibson M, Brana AF, Rohr J, Salas JA, Mendez C. Chem Commun. 2005:1604–1606. doi: 10.1039/b417815g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Melançon CE, III, Yu W-l, Liu H-w. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12240–12241. doi: 10.1021/ja053835o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamase H, Zhao L, Liu H-w. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:12397–12398. [Google Scholar]; (c) Borisova SA, Zhao L, Sherman DH, Liu H-w. Org Lett. 1999;1:133–136. doi: 10.1021/ol9906007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfoestl A, Hofinger A, Kosma P, Messner P. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26410–26417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.See Supporting Information for details.

- 9.Both the estimated amounts of 19–27 in crude extracts and isolated yields of 19–21, 23–27 are provided in Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.