Abstract

Tachyplesin-I is a cyclic β-sheet antimicrobial peptide isolated from the hemocytes of Tachypleus tridentatus. The four cysteine residues in Tachyplesin I play a structural role in imparting amphipathicity to the peptide which has been shown to be essential for its activity. We investigated the role of amphipathicity using an analog of tachyplesin I (TP-I), CDT (KWFRVYRGIYRRR-NH2), in which all four cysteines were deleted. Like TP-I, CDT shows antimicrobial activity and disrupts E. coli outer membrane and model membranes mimicking bacterial inner membranes at micromolar concentrations. The CDT peptide does not cause hemolysis up to 200 μg/mL while TP-I showed about 10% hemolysis at 100 μg/mL and about 25% hemolysis at 150 μg/mL. Peptide-into-lipid titrations under isothermal conditions reveal that the interaction of CDT with lipid membranes is an enthalpy driven process. Binding assays performed using fluorimetry demonstrate that the peptide CDT binds and inserts into only negatively charged membranes. The peptide-induced thermotropic phase transition of MLVs formed of DMPC and DMPC/DMPG (7:3) mixture suggest specific lipid-peptide interactions. The circular dichroism study shows that the peptide exists as an unordered structure in an aqueous buffer and adopts a more ordered β-structure upon binding to negatively charged membrane. The NMR data suggest that CDT-binding to negatively charged bilayers induces a change in the lipid head group conformation with the lipid head group moving out of the bilayer surface towards the water phase and therefore a barrel stave mechanism of membrane-disruption is unlikely as the peptide is located near the head group region of lipids. The lamellar phase 31P chemical shift spectra observed at various concentrations of the peptide in bilayers suggest that the peptide may neither function via fragmentation of bilayers nor by promoting non-lamellar structures. NMR and fluorescence data suggest that the presence of cholesterol inhibits the peptide binding to the bilayers. These properties help to explain that cysteine residues may not contribute to antimicrobial activity, and that the loss of hemolytic activity is due to lack of hydrophobicity and amphipathicity.

Tachyplesin I (TP-I) is a 17-residue (H2N-KWCFRVCYRGICYRRCR-CONH2) carboxamidated β-sheet antimicrobial peptide found in the acid extracts of hemocytes of the horseshoe crab, Tachypleus tridentatus (1, 2). It inhibits the growth of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (1) as well as MRSA (multidrug resistant staphylococcus aureus) and fungi (3). It also binds to lipopolysaccharides (1) and DNA (4). The antimicrobial activity is believed to originate from the peptide’s ability to permeabilize bacterial cell membranes (3, 5). Structural studies using NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) experiments have revealed that tachyplesin I adopts a β-hairpin structure in aqueous medium, which is stabilized by the two disulfide linkages (6, 7) and a more amphiphilic conformation in a micellar environment (8).

Since there is considerable current interest in developing new antibiotic compounds for pharmaceutical applications, recent studies have focused on developing peptide antibiotics that are free from Cys residues as they are easy and less expensive to produce. Studies showed that removal of disulfide bonds has significantly altered the antimicrobial activity of tachyplesin I (9-12). An acyclic tachyplesin I analog with all four cysteine SH groups protected by acetamidomethyl groups, has been shown to cause more membrane-disruption but much weaker membrane permeabilization than the parent cyclic peptide (11, 13). While replacement of Cys residues with acidic or aliphatic amino acids exhibited weaker antimicrobial activities than the parent peptide, replacement with aromatic amino acids has resulted in increased antimicrobial activity (12). However, the reason for the difference in the activities of these analogs is not clearly understood. While a β-hairpin conformation similar to the native peptide has been proposed for aromatic analogs (4Cys → Tyr and Phe) (8, 12), secondary structures of aliphatic analogs (4Cys → Asp, Ile, Leu, Val and Ala) differed significantly from that of tachyplesin I. Therefore, a specific conformation is not always a prerequisite for antimicrobial activity (12, 14).

To understand the consequences of deletion of all four cysteine residues in tachyplesin I, and in search of analogs with improved or adequate antimicrobial activity and cell selectivity, we synthesized an analog of Tachyplesin I, CDT (Cysteine Deleted Tachyplesin), in which all four cysteines were deleted. We investigated the hemolytic and antimicrobial activities of CDT and compared with that of TP-I, and its ability to disrupt the outer membrane of E. coli and to interact with model membranes mimicking bacterial and mammalian membranes. Peptide-induced membrane permeabilization was also studied using dye leakage experiments on model membranes that mimick the inner membranes of bacteria. To obtain information on the membrane selectivity, we measured the binding energy using ITC (isothermal titration calorimetry) and the binding affinity using fluorimetry. Specific lipid-peptide interactions were observed following the phase transition behavior of MLVs (multilamellar vesicles) formed of DMPC (1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine) and DMPC:DMPG (1,2-dimyristoyl- sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol) mixture using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments. The structure of the peptide CDT in an aqueous buffer and membrane-bound state were determined using circular dichroism (CD) experiments. Our results on the cell selective interactions of CDT are discussed in light of altered amphipathicity of the peptide and its binding enthalpy and affinity for anionic phospholipids.

Investigation on the molecular-level details of lipid-peptide interactions is important to understand the activity of the peptide. In this study, this is accomplished using 31P solid-state NMR experiments on model membranes with varying composition. It is known that the 31P chemical shift of a phospholipid is highly sensitive to the charge density near the lipid head group and could provide more information on the lipid-peptide interaction. Peptide-induced changes in the 31P isotropic and anisotropic chemical shift interactions and spin-lattice relaxation (T1) parameter of phospholipids were experimentally measured from unoriented MLVs. The experimental results are used to understand the role of anionic lipids and cholesterol, two key components by which the bacterial and mammalian cell membrane compositions differ, in the antimicrobial activity and selectivity of CDT.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Cholesterol was procured from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. LPS-H458 (isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain H458) was a gift from Robert E. W. Hancock, Canada. All protected amino acids, solvents and reagents were purchased from Bachem, Synthetech, Aldrich Chemical Co., Fisher Scientific and Protein Technologies.Tachyplesin I was purchased from Becham (King of Prussia, PA).

Peptide Synthesis

The peptide was prepared on a PS3 Automated Peptide Synthesizer from Protein Technologies using standard solid phase techniques for N-α-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) protected amino acids on Rink amide p-methylbenzhydrylamine (MBHA) resin (0.6 mmole/g). The side chain of Trp was protected as the t-butyloxylcarbonyl group. A 20% piperidine in N,N-dimethylformamide was used for deprotection. O-(Benzotriazol-1yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) was used for coupling. Deprotection and cleavage from the resin were accomplished using 11mL 90% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/10% scavenger cocktail (anisole, thioanisole, ethanedithiol, phenol, water). Crude peptides were purified to homogeneity by preparative reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography on a Waters instrument with a Phenomenex C18 column (2.2 × 25.0 cm, 10 mL/min). A linear gradient of 10% acetonitrile (0.1% TFA)/water (0.1% TFA) to 50% acetonitrile (0.1% TFA)/water (0.1% TFA) was employed. Liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy (Finnigan LCQ) confirmed the molecular weight (calculated: 1855.2; observed:1854.2).

Antimicrobial Assay

A doubling dilution series of the peptide, 100 μg/mL to 0.1 ng/mL, was added to the wells of sterile 384-well microtiter plate (12 replicates per dilution) and dried overnight. Bacterial suspensions (10 μL, 107/mL) were added to the wells, covered with a sterile plastic film, centrifuged briefly to collect the cells in the bottom of the wells and incubated at 37°C for 6 to 36 hours depending upon the rate of growth of bacterial species. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were set as the lowest concentration of the peptide at which there was no growth above the inoculated level of bacteria (p<0.05, n=12).

Hemolysis assay

The hemolytic activity of the peptides was determined by measuring the hemoglobin released from suspensions of fresh sheep erythrocytes. Red blood cells (Colorado Serum Company, Denver, CO) were centrifuged and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (0.15 M NaCl, 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). One hundred μL of red blood cells were added to the wells of a 96-well plate, and then 100 μL of the peptide solution (in PBS (phosphate buffered saline)) was added to each well. The plates were covered with an adhesive plastic sheet, incubated for 1 hour at 37°C and centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 min. Absorbance of the supernatants were measured at 414 nm. Zero and hundred percent hemolysis were determined in PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100, respectively.

Outer Membrane Disruption Assay

E. coli (strain BL21/DE3) cells from the mid-log phase were centrifuged and washed thrice with ice-cold HEPES (N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N’-[2-ethanesulfonic acid]) buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), and resuspended in the same buffer to an OD600 of 0.340. To a 3.0 mL cell suspension, a stock solution of ANS was added to a final concentration of 5.75 μM. The degree of membrane permeabilization as a function of the peptide concentration was observed by the increase in the fluorescence intensity at ∼500 nm.

Binding Experiments

The extent of peptide binding to liposomes was measured by adding SUVs (small unilamellar vesicles) to the peptide solution in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) and monitoring the changes in the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. After a 5-minute incubation period, fluorescence spectra were recorded on a ISA-Spex Fluoromax-2 spectrofluorometer, with the excitation set at 295 nm, using a 5 nm slit. To ensure complete binding, lipid vesicles were added until no further changes in the intensity or the emission maximum was observed. Contributions from the buffer and SUVs were subtracted from the experimental spectrum before normalization. Changes in the intensity at 338 nm (the emission maximum observed upon complete binding of the peptide) were used for calculating the partition coefficient (15-17), using the following formula: Xb = Kp Cf; where Xb is the molar ratio of bound peptide per total lipid, Cf is the equilibrium concentration of free peptide in solution and Kp is the partition coefficient.

High-sensitivity titration calorimetry

The heat of peptide-into-lipid mixing reaction was measured using a high sensitivity titration calorimeter (Calorimetry Sciences Corporation, Model CSC-4200, Utah, USA). Peptide and lipid solutions in HEPES buffer were degassed under vacuum prior to use. The calorimeter was calibrated as recommended by the manufacturer. The heats of dilution for successive 10 μL injections of the peptide solution (540 μM) into Tris (tris hydroxymethylaminoethane) buffer (pH 7.4) were insignificant compared to the heats of peptide-lipid reaction. The SUV-lipid concentration was 20 mM. The heat of peptide-lipid binding was determined by integrating the area under each titration curve using the built-in Bindworks software.

Dye leakage assay

Carboxyfluorescein dye entrapped small unilamellar vesicles were prepared and characterized as described elsewhere (18). The dye-containing vesicles were then purified by gel filtration chromatography, using a Sephadex G-75 column. Fluorescence emission intensity as a function of time was recorded using the excitation wavelength 490 nm and emission wavelength 520 nm. The maximum leakage from each sample was determined by adding Triton X-100.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Lipid films of DMPC and DMPC:DMPG (7:3) were prepared by mixing the lipid and peptide in chloroform in the desired molar ratio, drying the sample under a gentle stream of nitrogen, and then placing under vacuum for ∼10 hours to remove any residual solvent. The dried samples were hydrated with tris buffer (10 mM tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), and then vortexed above the main phase transition temperature of the lipid to obtain MLVs.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Small unilamellar vesicles were prepared by sonication. LPS-H458 was suspended in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluro-2-propanol and mixed with POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine) in chloroform and the clear solution was dried under vacuum for ∼12 hours. Tris buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) was added to the dry lipid film and subjected to vortex and sonication to obtain SUVs. CD spectra were recorded (AVIV CDS Model 62DS spectropolarimeter, Lakewood, NJ) at 24.2°C using a 1.0 mm quartz cuvette over the range from 200 to 250 nm. Contributions from the buffer and SUVs were removed by subtracting the spectra of corresponding control samples without peptide.

Solid-state NMR

Mechanically aligned bilayers were prepared using the procedure described by Hallock et al. (19). Briefly, 4 mg of lipids and an appropriate amount of peptide were dissolved in CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1) mixture. The sample was dried under a stream of nitrogen and re-dissolved in CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1) mixture containing equimolar quantities of naphthalene. An aliquot of the solution (∼300 μL) was spread on two thin glass plates (11 mm × 22 mm × 50 μm, Paul Marienfeld GmbH & Co., Bad Mergentheim, Germany). The samples were then air-dried and kept under vacuum at 35°C for at least 15 hours to remove naphthalene and any residual organic solvents. After drying, the samples were hydrated at 93% relative humidity using saturated NH4H2PO4 solution (20) for 2-3 days at 37°C, after which approximately 2 μL of H2O was added to the surface of the lipid-peptide film. The glass plates were stacked, wrapped with parafilm, sealed in plastic bags (Plastic Bagmart, Marietta, GA), and then kept at 4°C for 6-24 hours.

Multilamellar vesicles were prepared by mixing the required amounts of lipid and peptide in 2:1 chloroform:methanol. The solution was first dried under N2 gas and then under vacuum overnight to completely remove any residual organic solvents. The mixture was resuspended in 50 weight % water by heating in a water bath at 45°C. The samples were vortexed for 3 min and freeze-thawed using liquid nitrogen several times to obtain a uniform mixture of lipid and peptide.

31P NMR experiments were performed on a Varian Infinity 400 MHz solid-state NMR spectrometer operating at a resonance frequency of 161.979 MHz. A Chemagnetics temperature controller was used to maintain the sample temperature, and each sample was equilibrated at 30°C for at least 25 minutes before the experiment. A home-built double resonance probe, which has a four-turn square-coil (12 mm × 12 mm × 4 mm) constructed using a 2 mm wide flat-wire and a spacing of 1 mm between turns, was used for experiments on aligned samples and a double-resonance MAS (magic angle spinning) probe was used for experiments on MLVs. In the case of aligned samples, the lipid bilayers were positioned with the bilayer normal was parallel to the external magnetic field of the NMR spectrometer. A typical 31P 90° pulse length of 3 μs was used. 31P spectra were obtained using a spin echo sequence (90°-τ-180°τ-acquire with τ = 90 μs), 55 kHz rf field for time proportional phase modulation decoupling of protons (21), 50 kHz spectral width, and a recycle delay of 3 seconds. A typical spectrum required the co-addition of 200-600 transients for aligned samples and about 4,000 transients for MLVs. The 31P chemical shift spectra are referenced relative to 85% H3PO4 (0 ppm) (19). The 31P longitudinal relaxation time (T1) measurements were performed using an inversion-recovery pulse sequence, 180°-τ-90°-acquire, with proton decoupling and a 3 s recycle delay. Data processing was accomplished using the Spinsight software (Varian) on a Sun Sparc workstation.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial activity and membrane permeabilization

The MICs of tachyplesin I and CDT against various bacteria determined as described in the experimental section are given in Table 1. Both the peptides exhibited similar activities against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria at micromolar concentrations, although they were inactive against Bascillus subtilis. Since the antimicrobial activity of tachyplesin I has been coupled with membrane permeabilization(11, 13), the ability of CDT to permeabilize bacterial outer membrane was assayed using ANS dye. The fluorescence of ANS is quenched by the polar water molecules in buffer and significantly enhanced when ANS partitions into the hydrophobic region of cell membranes (18, 22). As shown in Figure 1, CDT effected dose-dependent changes in the steady state fluorescence spectrum of ANS, when the peptide was incubated with E. coli cells. The control experiment in which E. coli cells were incubated with ANS dye (without peptides) showed no time-dependent changes in the fluorescence spectrum. The dose-dependent maximal fluorescence intensity and the associated blue shift in the emission maximum of ANS illustrate the CDT-induced permeability changes in E. coli outer membrane satisfactorily. However, CDT failed to induce any observable leakage of hemoglobin from sheep erythrocytes up to 200 μg/mL indicating the peptide’s inability to permeabilize erythrocyte membrane (data not shown).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of tachyplesin (TP-I) and cysteine deleted tachyplesin (CDT) against different microbes

| Bacteria (OD600 = 0.002) | TP-I MIC (μg/mL) | CDT MIC (μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ATCC 12014 | 11.5 | 6.25 |

| B. subtilus | ATCC 11774 | >200 | >200 |

| P. aeruginosa | ATCC 10145 | 8.25 | 12.5 |

| L. monocytogenes | ATCC 15313 | 23.5 | 12.5 |

| S. enterica | ATCC BAA-215 | 16.25 | 12.5 |

| E. faecalis | Strain FA1 | 100 | 100 |

| P. gingivalis | Strain 33277 | 3.125 | 3.125 |

Figure 1.

E. coli outer membrane permeabilization: cell density at OD600=0.340; Concentration of ANS was 5.75 μM. Peptide concentrations were (a) 0, (b) 0.359, (c) 0.718, (d) 1.08, and (e) 1.436 μM.

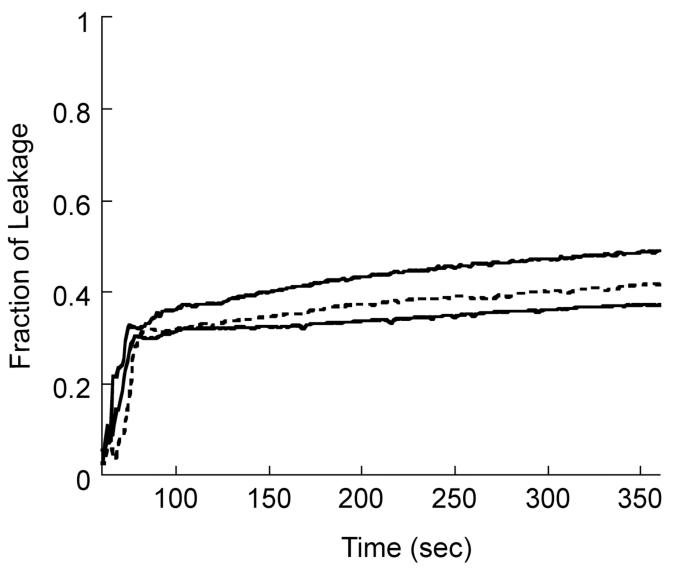

To understand the permeabilization of inner membranes by CDT, we performed dye leakage experiments on model membranes (7:3 POPC:POPG) mimicking bacterial inner membranes at 30°C. SUVs containing carboxy-fluorescein dye were prepared as described in the experimental section (18). The leakage of dye was observed as a function of time for different concentrations of CDT and the results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Extent of carboxyfluorescein dye leakage from 7:3 POPC:POPG vesicles was fluorimetrically detected at 30°C as a function of time for different peptide concentrations: 1.8 μM (bottom trace), 2.4 μM (dashed lines) and 3.6 μM (top trace). Lipid concentration was 60 μM.

Binding to lipid vesicles

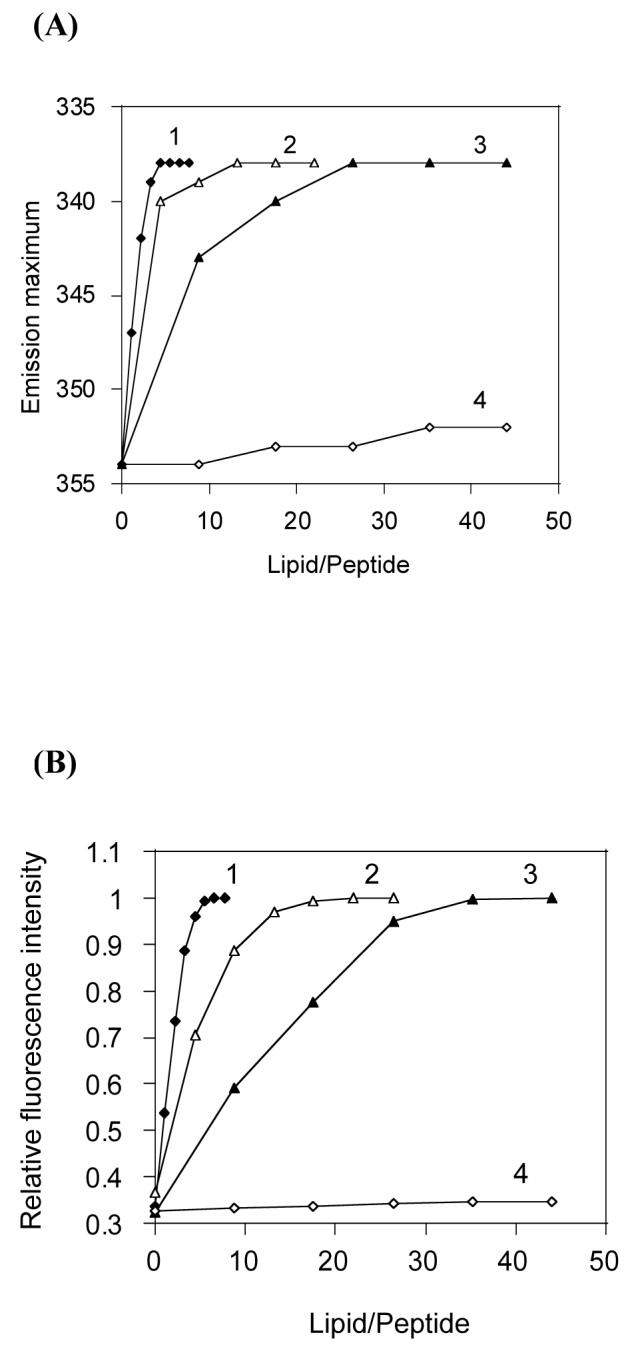

The binding affinity for different lipids was determined by titrating a fixed concentration of peptide with SUVs of different lipid compositions. We used SUVs in order to minimize the light-scattering effects (23). Spectra were normalized after subtracting the contributions from buffer and lipid vesicles. The changes in the intrinsic fluorescence emission maximum of CDT were plotted as a function of the lipid/peptide molar ratio for different lipid vesicles. It is apparent from Figure 3A that CDT partitions into negatively charged vesicles and adheres to the surface of zwitterionic POPC:cholesterol (7:3) vesicles. A plot of the changes in fluorescence intensity at 338 nm (the emission maximum observed upon complete binding) versus the lipid-peptide ratio is presented in Figure 3B. The average molecular weight of LPS isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been calculated to be ∼20 kDa; this value was used in determining the lipid:LPS value of the sample used in the experiment. The lipid-peptide ratios required for complete binding of the peptide reflect the relative binding affinities for different membranes. The experimental binding isotherm for different SUVs which results from the plot of Xb versus the concentration of the free peptide is given in Figure 3C. The partition coefficients estimated from the initial slopes of the binding curves are presented in Table 2. Binding of CDT to POPC:cholesterol (7:3) SUVs resulted in minimal changes in the fluorescence emission spectra and therefore the partition coefficient could not be determined. An analysis of Figures 3(A and C) shows a direct relation between the degree of membrane insertion and partition coefficient.

Figure 3.

Shift in the fluorescence emission maximum of CDT (A) and increase in the fluorescence intensity at 338 nm (B) upon binding to lipid vesicles: (1) Filled diamonds, POPC/LPS (61:1); (2) open triangles, POPC/POPG (7:3); (3) filled triangles, POPE/POPG (7:3); (4) open diamonds, POPC/Cholesterol (7:3). (C) Binding isotherms derived from Fig. 3B by plotting Xb (extent of binding) versus Cf (free peptide).

Table 2.

Enthalpy of binding (ΔH) and partition coefficient (Kp) values of CDT for different lipid vesicles

| SUVs | ΔH (kJ/mol)a | Kp (104 M-1)a |

|---|---|---|

| POPC/LPS-H458 (61:1) | -43.7 | 12.2 |

| POPC/POPG (7:3) | -36.6 | 4.92 |

| POPE/POPG (7:3) | -18.8 | 0.78 |

| POPC/Cholesterol (7:3) | -10.4 | ----b |

Average of three independent experiments. The error was <8%.

Not determined.

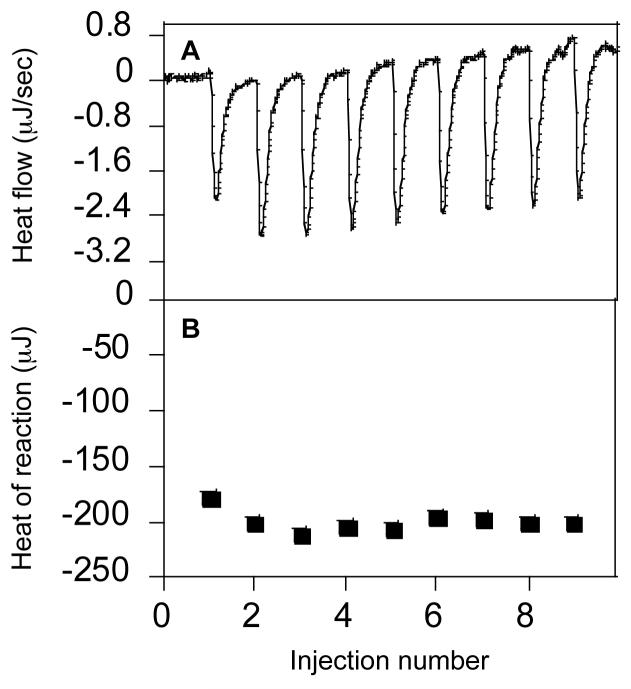

Binding energy

To estimate the binding energy associated with CDT interactions with different membranes, we determined the heat evolved during the binding process using ITC. The calorimetric trace showing the heat liberated during successive 10 μL injections of the peptide solution into POPC:LPS (lipopolysaccharides) (61:1) lipid vesicles is presented in Panel A, and the heat of reaction is given in Panel B of Figure 4. The enthalpies of binding to different lipid vesicles are summarized in Table 2. While the binding of CDT to LPS containing vesicles yielded the highest enthalpy (-43.7 kJ/mol), binding to cholesterol containing vesicles produced the lowest heat of reaction (-10.4 kJ/mol). The binding enthalpies for different membranes correlate with the partition coefficients of CDT for these membranes (Figure 3). The low enthalpy observed for POPC:cholesterol (7:3) may be due to weak interactions of the peptide with the lipid head group region of the membrane (24).

Figure 4.

Titration calorimetry thermograms of POPC/LPS (7:3) SUVs (20 mM) were titrated against a solution of CDT (540 μM) in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) at 25°C. Aliquots of a 10 μL peptide solution were injected to the vesicle suspension in the reaction cell (V = 1.280 mL). Panel A shows the calorimeter trace. The enthalpy of reaction, which is calculated by integration of the calorimeter traces using the built-in Bindworks software, is given in panel B.

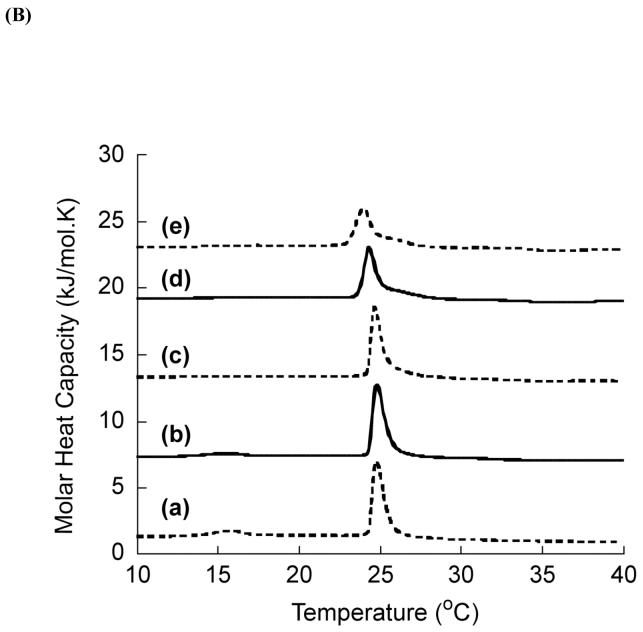

Specific lipid-peptide interactions

DSC is a sensitive method to study the effect of peptide incorporation in the thermotrophic phase transition behavior of lipid bilayers (25). The DSC thermograms were obtained from DMPC and in the presence of various concentrations of the peptide. For clarity, the thermograms obtained from DMPC and DMPC:CDT (∼7:1) are presented in Fig. 5A. The enthalpies calculated for pure DMPC and DMPC incorporated with different amounts of CDT are comparable as the main phase transition behavior of DMPC MLVs are influenced only marginally by the presence of CDT. At a lipid:peptide ratio of ∼7:1, there is a very little effect on the transition from the gel to liquid-crystalline (Lα) phase at ∼24.8°C. Insignificant changes in the phase transition temperature (Tm) indicate that the peptide does not alter the packing of the hydrocarbon chains of DMPC in the gel and liquid-crystalline states (26-28). Our experiments show that the presence of 7.32 mol% of the peptide CDT does not seem to have affected significantly the pretransition arising from the lamellar gel (Lβ’) to lamellar rippled gel (Pβ’) phase.

Figure 5.

DSC thermograms of: (A) DMPC MLVs incorporated with (a) 0 and (b) 7.32 mol % of the peptide; (B) DMPC:DMPG (7:3) MLVs incorporated with (a) 0, (b)0.366, (c) 1.464, (d) 3.66 and (e) 7.32 mol% of the peptide.

The effect of CDT on the phase transition of negatively charged DMPC:DMPG (7:3) MLVs is shown in Fig 5B. As evident from the figure, the DMPC:DMPG (7:3) MLVs showed a pretransition at 16°C and the main transition at 24.8°C (27, 28). Incorporation of 0.366 mol% of CDT into DMPC:DMPG (7:3) MLVs showed a reduction in temperature and enthalpy of both the pretransition and main transition. The presence of increasing quantities of CDT produced progressive reduction in the main phase transition temperature as well as enthalpy. Consequently, the incorporation of 1.464 mol% of CDT resulted in the abolition of the pretransition and the emergence of a two-component main-transition. The relative contributions of the high melting broad component of the main transition also became more prominent at higher peptide concentrations. While the sharp component at 24°C is attributed to the hydrocarbon chain melting of the peptide-poor lipid domain, the broad high melting component is believed to arise from the peptide-rich lipid domain. Since the peptides that adapt transmembrane orientation contribute to a large enthalpy of transition, the observed low enthalpy values (Table 3) suggest that CDT does not insert deeply into the hydrophobic region of DMPC:DMPG membrane and is likely to be located at the membrane-water interface. The consistent decrease in the Tm and enthalpy of the sharp component of the thermograms may be ascribed to decreasing size of the peptide-poor domain as the concentration of peptide is increased.

Table 3.

Thermotropic parameters of the gel to liquid crystalline phase transition of DMPC and DMPC:DMPG (7:3) MLVs incorporated with different amounts of CDT

| MLVs | Tm (°C) | ΔH (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Pure DMPC | 24.3 | 9.4 |

| DMPC + 7.32 mole % CDT | 24.4 | 9.1 |

| In DMPC/DMPG (7:3) | ||

| 0 mole % CDT | 24.8 | 7.8 |

| 0.366 mole % CDT | 24.8 | 7.0 |

| 1.464 mole % CDT | 24.6 | 6.4 |

| 3.660 mole % CDT | 24.3 | 5.7 |

| 7.320 mole % CDT | 23.9 | 4.9 |

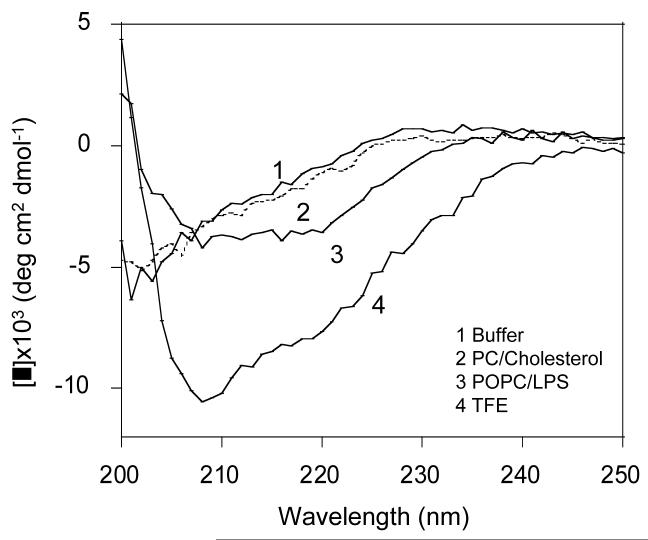

Secondary Structure

A high-resolution structure of tachyplesin I determined using NMR spectroscopy has been reported (6). This structure consists of an antiparallel β-sheet connected by a β-turn and two disulfide bonds that render rigidity to the structure with flexible N-and C-termini. Previous CD studies have compared the secondary structures of TP-I and its linear derivatives in solution, TFE/water and model membranes (12). In the present study we have analyzed the secondary structure of CDT and compared it with that of TP-I to understand its interaction with membranes.

The CD spectra of CDT are given in Figure 6, while the spectra of TP-I were similar to the published data and are not given here (9, 12). In aqueous buffer (Fig. 6, trace 1), CDT showed a negative minimum ∼ 202 nm, a cross over at 224 nm and positive ellipticity values above 224 nm. These characteristics reflect the existence of a largely unordered structure (12). Since the four residues that form the β-turn in TP-I are retained in the middle of the sequence of CDT, it is likely that the turn structure exists in CDT (29). However, contributions from the aromatic residues might also cause small differences in CD curve shapes (30). The CD spectra of CDT in the structure promoting solvent trifluoroethanol were recorded to assess the intrinsic ability of the peptide to adopt β-structures in membrane mimicking environment. The CD profiles of CDT in trifluoroethanol exhibited two bands at ∼208 and ∼220 nm, suggesting the existence of ordered/helical and β-structures (Fig. 6, trace 4).

Figure 6.

CD spectra of CDT in buffer and in the presence of lipid vesicles. Spectra were recorded in Tris buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) (trace 1), 7:3 POPC/cholesterol (trace 2), 7:3 POPC/LPS (trace 3), and 85% trifluoroethanol (trace 4). Addition of the peptide to 7:3 POPC/POPG and 7:3 POPE/POPG vesicles resulted in turbidity and hampered structure determination. Peptide and lipid concentrations were 0.133 mg/mL and 0.666 mg/mL, respectively. Spectra were recorded at 24.2°C.

In the presence of neutral POPC:Cholestrol (7:3) liposomes, the CD spectrum of CDT showed no characteristic features attributable to any defined peptide secondary structure (Fig. 6, trace 2). This might suggest that the peptide does not bind to the membrane or binds weakly to the membrane and the membrane induced structural changes in the peptide are minimum. However, in the presence of POPC:LPS (61:1) liposomes, CDT gave two broad negative bands at ∼ 208 and 218 nm (Fig. 5A, trace 3). These features clearly indicate conformational changes in CDT upon partitioning into POPC:LPS (61:1) liposomes and induction of a more ordered structure, perhaps a combination of extended and β-structures. Addition of peptide to POPC:POPG (7:3) and POPE (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine):POPG (7:3) liposomes resulted in turbidity, impeding structure determination (data not shown). These observations are consistent with previous reports on the CD profiles of Tachyplesin I (6, 9, 12, 31) and its analogs (9, 12, 31), and suggest that the mode of interaction of CDT is modulated by lipid compositions.

Peptide-induced structural changes in lipid bilayers using solid-state NMR experiments

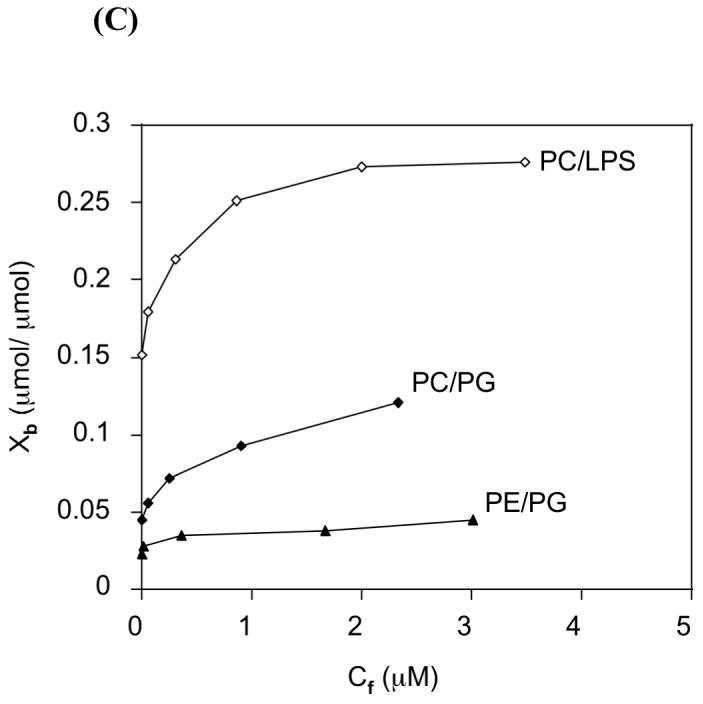

Based on the experimental results presented above, the cationic CDT peptide is strongly attracted towards bacterial type model membranes, which could be an important factor in the antimicrobial activity and selectivity of this peptide. Therefore, it would be useful to understand the details of lipid-peptide interaction at a higher resolution using solid-state NMR experiments. We carried out static 31P solid-state NMR experiments on mechanically aligned bilayers of varying composition with the bilayer normal parallel to the external magnetic field at 37°C and the results are given in Figure 7. The presence of a single narrow line at the higher frequency (or the parallel) edge (∼ 30 ppm) of the powder pattern (that was obtained from MLVs) indicates that the POPC bilayer sample was well-aligned (Figure 7A) (19). Spectra obtained from POPC bilayers containing various concentrations (up to 7 mole %) of the CDT peptide showed no significant changes due to peptide interaction with POPC bilayers; a sample spectrum obtained from POPC bilayers containing 7 mole % CDT is shown in Figure 7B. The 31P chemical shift spectrum of oriented bilayers composed of 7:3 POPC:POPG lipids (with no peptide) shows a peak at a frequency slightly shifted upfield (Figure 7C) relative to the POPC sample (Figures 7A and B) as the presence of an anionic lipid POPG reduces the span of the 31P chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) tensor (32-35). Incorporation of CDT to 7:3 POPC/POPG bilayers induced significant changes in the 31P lineshape due to peptide-induced disordering of the lipid head group (Figures 7D and E). As seen in Figures 7(D and E), the lipid-peptide interactions lead to broadening of the peak ∼28 ppm, which arises from a combination of POPC (most likely unperturbed) and POPG (most likely perturbed) lipids in the sample. This observation suggests that the peptide induces a change in the lipid head group conformation. In addition, at a higher concentration of CDT a low intensity broad line ∼-10 ppm appeared (Figure 7E), which could be due to the peptide-induced disordering of lipids in the sample. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 7F, the addition of 20 mole % cholesterol to 7:3 POPC:POPG bilayers containing 5 mole % peptide reduced the peptide-induced disorder that was observed in the absence of cholesterol. This suggests that the presence of cholesterol inhibits the membrane interaction of CDT.

Figure 7.

31P chemical shift spectra of oriented bilayers with the bilayer normal parallel to the magnetic field at 37°C: POPC bilayers with 0 mole % (A) and 7 mole % (B) CDT; 7:3 POPC:POPG bilayers with 0 mole % CDT (C), 3 mole % CDT (D), 5 mole % CDT (E) and 5 mole % CDT + 20 mole cholesterol (F).

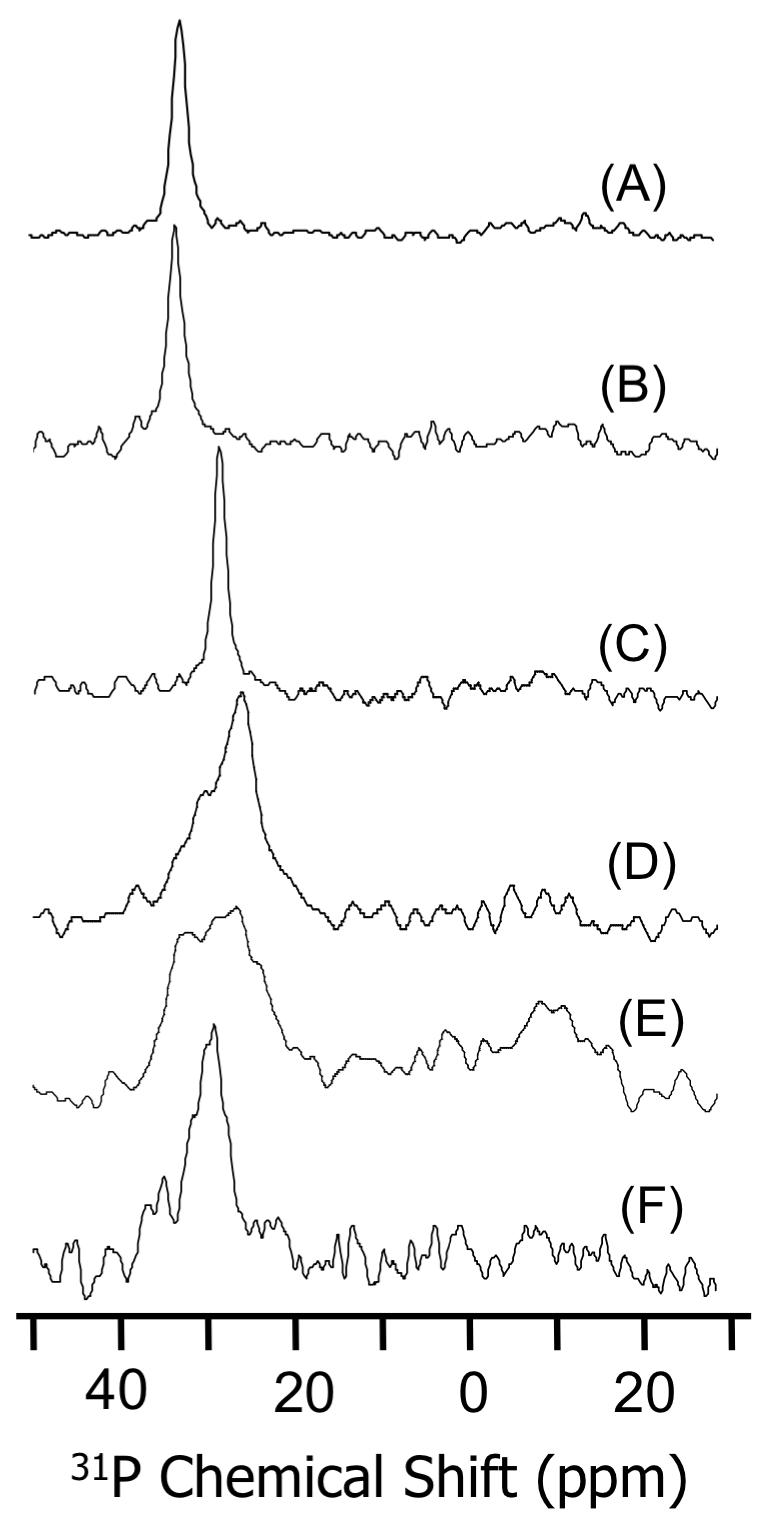

While it is clear that CDT alters the head group conformation of bilayers containing anionic lipids and the results were reproducible, lack of bulk water in aligned samples or sample handling procedures may have a role in the observed changes in the presence of the peptide. So, 31P NMR experiments were also carried out on static MLVs to measure the peptide-induced changes in the chemical shift span and the line shape. The 31P chemical shift spectra of pure POPC and 7:3 POPC:POPG at 37°C showed typical lamellar phase powder patterns with a chemical shift span of 46±1.5 ppm (data not shown) and 35±1.5 ppm (Figure 8), respectively. These chemical shift anisotropy values are in good agreement with the reported studies in the literature (33, 35). The addition of the CDT peptide (up to 10 mole % peptide) did not show significant observable changes (within experimental errors) in the spectral line shape of POPC bilayers while a notable increase in the span of the CSA tensor was observed in POPG containing bilayers. The CSA span values measured from POPC and 7:3 POPC:POPG MLVs containing 5 mole % CDT at 37°C were 46±1.5 ppm (data not shown) and 41±1.5 (Figure 8) ppm, respectively. Broadening at the high field region and reduced signal-to-noise ratio at the low-field region of the line shape in POPC:POPG bilayers are because the observed lineshape is a combination of signal intensities from two different lipids as reported in the previous studies (33-35). On the other hand, a combination of responses from lipids in the peptide-rich (most likely dominated by POPG) and peptide-poor (most likely dominated by POPC) domains could contribute to the lineshape observed in the presence of the peptide. The increase in the CSA span due to the cationic CDT peptide binding to bilayers is in good agreement with the previous studies on the effect of cations on lipid bilayers (32, 35, 36). These 31P NMR results also suggest that CDT neither promotes the formation of non-lamellar phase structures such as cubic and hexagonal phases nor fragments the MLVs to micelles or SUVs, as their lineshapes are significantly different from the observed lamellar phase spectra.

Figure 8.

31P chemical shift spectra of 7:3 POPC:POPG multilamellar vesicles 37°C with different concentrations of the CDT peptide (given in mole %).

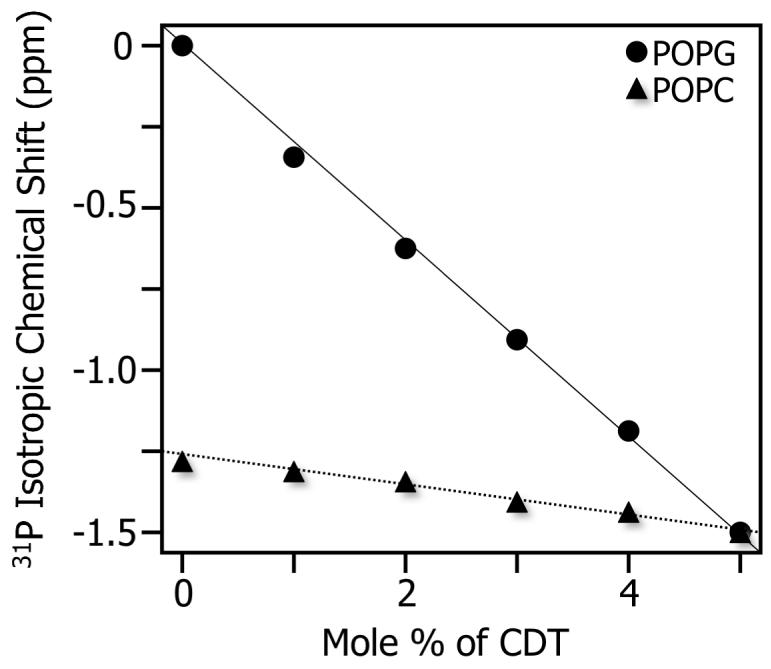

In addition to the results obtained from oriented bilayers (Figure 7) and static MLVs (Figure 8), magic angle spinning (MAS) 31P NMR experiments were also performed on MLVs at 37°C. MAS experiments required much less sample quantity than static experiments on MLVs. The MAS spectra consisted a narrow line for a pure POPC sample and two narrow lines for 7:3 POPC:POPG sample separated by about ∼1.3 ppm (the low field peak corresponds to POPG and the high field peak corresponds to POPC) as reported for DMPC and DMPG bilayers (36). The 31P isotropic chemical shift frequency was measured from POPC and 7:3 POPC:POPG bilayers containing various amounts of the peptide (Figure 9). The addition of CDT to POPC bilayers did not change the 31P chemical shift frequency, whereas an upfield shift of both the 31P peaks corresponding to POPC and POPG lipids in 7:3 POPC:POPG bilayers was observed. The upfield shift for the POPG is greater than that of the POPC value as shown in Figure 9. These results demonstrate that the presence of an anionic lipid (POPG) enables the interaction of the peptide CDT to bilayers and also confirm the peptide-induced head group conformation change of lipids.

Figure 9.

Variation of 31P isotropic chemical shift of 7:3 POPC:POPG multilamellar vesicles under 3 ± 0.005 kHz MAS as a function of the concentration of CDT peptide. The isotropic chemical shift value of POPG (circles) was set to 0 ppm while that of POPC (triangles) was at -1.3 ppm in the absence of the peptide. A 0.25 ppm experimental error in the chemical shift value was measured from the full width at half maximum.

Peptide-induced changes in the 31P spin-lattice relaxation (T1) values of MLVs at 37°C were also measured using MAS experiments. The addition of 5 mole% CDT slightly changed the T1 value from 775±10 to 790±10 ms in POPC bilayers. On the other hand, the addition of 5 mole % CDT increased the T1 values for both POPC and POPG lipids in 7:3 POPC:POPG bilayers. However, the increase in the T1 value of POPG (from 785±10 to 890±10 ms) is significantly larger than that of POPC lipid (from 780±10 ms to 810±10 ms). The increase in T1 values in the presence of the peptide suggests that the lipid-peptide interaction most likely reduces the axial rotational motion of the lipids, which could make the T1 relaxation mechanism less efficient as reported in a recent study (37). These results further confirm the preference of the peptide to bind with anionic lipids in the bilayer.

DISCUSSION

Linearization of cyclic antimicrobial peptides generally alters their activities as well as their ability to interact with membranes (9-13, 31, 38, 39). Matsuzaki et al have shown that a linear analog of tachyplesin I, where all four SH groups of Cys residues are protected with acetamidomethy groups, exhibited more membrane disruption but much weaker membrane permeabilization activity than the parent peptide (11, 13). To better understand the relationship between the structure and activity of TP-I, Rao studied several linear analogs of TP-I (12). These linear peptides replaced Cys residues of TP-I with amino acids differing in side chain properties such as aliphatic hydrophobic (Ala, Leu, Ile, Val, and Met), aromatic hydrophobic (Phe and Tyr) and acidic (Asp). Based on the structural and activity measurements, it was concluded that the rigidly held β-sheet structure may not be absolutely essential for antimicrobial activity (12). These studies have provided excellent insights into the activity of TP-I and will be useful in the design of potent antimicrobial peptides. Since the substitution of Cys in TP with other amino acids alters the structural folding and function of the peptide in membranes (11-13), in this study, we investigated the effect of deletion of Cys residues on the activity of TP-I.While tachyplesin I is a 17-residue amphipathic peptide with a rigid β-structure, its analog CDT is a 13-residue linear peptide. Both tachyplesin I and CDT have a net charge of 7+, but a deletion of four cysteine residues makes CDT less ordered and less hydrophobic than tachyplesin I.

Deletion of cysteine residues does not affect antimicrobial activity

The peptide CDT shows antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria at micromolar concentrations (Table 1). These concentrations are comparable with the MIC values of tachyplesin-I (Table 1). Thus, the cysteine residues in tachyplesin I may not be essential for the antimicrobial activity. Several cationic antimicrobial peptides have been found to bind preferentially to anionic lipids (40) and bacterial lipopolysaccharides (41, 42). Since CDT is rich in basic amino acids, the observed antibacterial activity is likely to stem from the peptide’s affinity for negatively charged cell surface components such as LPS on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and lipoteichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria (43). Antimicrobial peptides that have the ability to interact with membranes are known to compromise the permeability barriers of bacterial membranes (44, 45). The peptide CDT also induces ANS uptake into E. coli membrane in a concentration dependent manner by effectively disrupting the outer membranes (Fig. 1). The dye leakage experiments suggest that the peptide is also effective in permeabilizing model membranes (7:3 POPC:POPG) that mimick the bacterial inner membranes (Fig. 2). It is interesting to note that CDT does not cause hemolysis even at 200 μg/mL. On the other hand, TP-I showed about 10% hemolysis at 100 μg/mL and about 25% hemolysis at 150 μg/mL. These data show that the deletion of all four cysteine residues in tachyplesin I leads to the abolition of only the hemolytic activity and not the antibacterial activity. A previous study reported no or very little hemolytic activity for TP-I and its linear analogs (where Cys residues are replaced with other amino acids as mentioned earlier) on rabbit erythrocytes at low concentrations but certain analogs (TPM, TPF and TPY where Cys replaced with the underlined residue) showed about 30% lysis for concentrations >80 (12). On the other hand, TP-I and an amidated version of TP-I showed about 15% and 30% lysis, respectively, on human erythrocytes (12). Therefore, the physicochemical parameters that are related to this remarkable cell selectivity of CDT could be important in understanding the function of the peptide as well as in designing potential compounds for pharmaceutical applications.

Bacterial cell selectivity correlates with anionic lipid specific binding

Since CDT showed only antibacterial activity and no hemolytic activity, we investigated the binding of CDT to neutral and acidic liposomes to find if any correlation exists between the binding characteristics and cell selectivity. CDT shows a weak affinity for neutral membranes as opposed to acidic membranes (Fig. 3B). An analysis of figures 3A and 3C shows that the extent of membrane penetration correlates with the partition coefficient. Similar results were obtained from ITC experiments (Fig. 4 and Table 2). Collectively, these data show that CDT has a high affinity for negatively charged membranes with the highest affinity being for POPC:LPS (61:1) vesicles. A similar observation on the LPS specific interactions of TP-I have been reported recently (31). Both TP-I and CDT possess seven positive charges and the deletion of the four cysteine residues does not seem to affect the LPS binding affinity. The observed LPS selectivity of CDT, which can be explained in terms of electrostatic interactions (46,47), correlates well with the observed antibacterial activities. A similar behavior has been observed with magainin 2 (48), analogs of gramicidin S (49) and diastereomeric peptides (47, 50), which exhibit antimicrobial activity with little hemolytic activity. It is likely that the presence of acidic phospholipids, especially the LPS, in the membranes contributes to bacterial susceptibility to these peptides as well as CDT.

From the DSC results shown in Figure 5B and Table 3, it is evident that the incorporation of different amounts of CDT affects both the pretransition and the main phase transition of anionic MLVs made of DMPC:DMPG (7:3) mixture. It is interesting to note that at a peptide concentration of 1.464 mol%, the gel to rippled gel phase transition disappears completely while the main phase transition associated with the trans-gauche isomerization in the lipid acyl chains is not affected significantly. Since membrane-spanning peptides are known to affect the rippled gel to liquid crystalline phase transition significantly (28), our observations indicate that the peptide CDT is located at membrane interface and does not insert deep into the hydrophobic portion of the membrane. This assumption is also supported by the observed blue shift (Fig. 3A) in the fluorescence emission of CDT bound to all the three anionic lipid vesicles chosen for this study. The formation of peptide-rich and peptide-poor domains in the case of DMPC:DMPG (7:3) MLVs, which is not observed with DMPC MLVs, reflect the peptide’s affinity for anionic lipids and suggests a possible mechanism for the observed antimicrobial activity of CDT. Formation of a specific lipid-peptide complex can result in the segregation of lipids in the membrane. This in turn can result in the formation of local defects in the membrane, which may provide the basis for the induction of transient lesions and membrane leakage. Thus, the peptide-induced E. coli membrane disruption (Fig. 1) is in agreement with the peptide’s ability to interact specifically with anionic lipids.

31P NMR data suggest that the CDT peptide binding leads to a significant structural changes in bilayers containing an anionic lipid (7:3 POPC:POPG) and no changes in zwitterionic lipid bilayers (POPC) (Figures 7-9), which also agrees well with the low binding affinity for the peptide to bilayers containing no anionic lipid. The observed chemical shift values from aligned bilayers indicate that the peptide induces orientational disordering only in bilayers containing POPG lipid (Figure 7) (51-53). Interestingly, the addition of cholesterol significantly reduces the disorder induced by the peptide (Figure 7). The increase in the 31P chemical shift span measured from experiments on unoriented MLVs containing POPG and CDT suggests that the peptide-lipid interaction alters the lipid head group conformation; whereas no changes were observed for POPC bilayers in the presence of CDT (Figure 8). This interpretation is supported by the upfield shift of the isotropic 31P chemical shift frequency measured using MAS experiments on MLVs composed of 7:3 POPC:POPG and CDT (Figure 9). These results and interpretations are in good agreement with the previously reported NMR studies on bilayers containing cationic amphiphiles (32, 35, 36, 53). The increased T1 values in the presence of CDT suggest that a reduced motion of lipids due to peptide binding reduces the efficiency of the relaxation mechanism. This is in good agreement with a recent NMR investigation of lipid-peptide interaction (37).

While NMR results are consistent with the results from other biophysical (ITC, DSC and fluorescence) experiments presented in this paper, NMR results can be used to understand the change in the conformation of the lipid head group at a higher resolution. Since the CDT peptide is highly cationic (+7 net charge), the effect of its binding to the lipid bilayer surface could be very similar to the changes induced by the addition of cationic amphiphiles which are well characterized (32, 35, 36). This assumption is valid as the observed chemical shift changes in static as well as MAS experiments are similar in both the cases. Therefore, based on the studies from cationic amphiphiles and the NMR data reported in this paper, the CDT peptide interaction with lipids causes the lipid head group to move out of the bilayer plane into the water phase (32). This arrangement is favored in POPG containing bilayers as POPG is an anionic lipid and the electrostatic interaction between the peptide and the lipid is the major driving force. On the other hand, such effect was not observed in POPC containing bilayers as the positively charged choline group could repel the cationic peptide. This also explains the selectivity of the peptide towards bacterial membranes which contain ∼25% anionic lipids while the mammalian membranes contain a large quantity of POPC lipids and its outer leaflet contains negligible amount of anionic lipids. The selectivity of the peptide is further enhanced by the presence of cholesterol in mammalian membranes, which is shown to inhibit the lipid-peptide interactions (see Figure 6 and also the fluorescence data given below).

Since the 31P data (Figures 6 and 8) suggest that the peptide is located near the lipid head group, it is unlikely that the peptide would function via a barrel-stave type mechanism of membrane-disruption (40, 55). On the other hand, the observation of lamellar phase powder pattern spectra in the presence of the peptide (Figure 7) and absence of an isotropic peak or peaks corresponding to non-lamellar phases (Figures 6 and 7) suggest that the peptide may neither function via the induction of non-lamellar lipid structures nor by the fragmentation of membranes (52, 56). Therefore, a general carpet-type mechanism, where the peptides are located on the bilayer surface which may further lead to membrane-disruption by a flip-flop process as proposed for polyphemusin peptides (57), and/or a toroidal-type pore formation (45, 46, 48, 58) as observed for magainin peptides or via other possible mechanisms reported for various antimicrobial peptides could explain the antimicrobial activity of CDT (56-64).

31P NMR experiments were also performed on POPC, 7:3 POPC:POPG and 7:3 POPC:cholesterol bilayers containing TP-I under similar conditions as mentioned above. No observable peptide-induced changes in the 31P chemical shift spectra of mechanically aligned bilayers and unaligned MLVs of these samples were measured for TP-I concentrations up to 5 mole % (data not shown). These results suggest that the peptide does not significantly alter the lipid head group conformation and therefore it is most likely inserted in to the bilayers. This is in excellent agreement with a previous study by Matsuzaki et al. which reported that the TP-I peptide binds to negatively charged bilayers without significantly perturbing the membrane structure, translocates across the bilayer coupled with the pore formation in anionic (PG-containing) bilayers without altering the vesicle morphology, and forms anion-selective ion channels (11). In contrast, the same study reported that a linear analog of TP-I (all Cys protected by acetamidomethyl groups) significantly disrupted bilayers and failed to translocate. However, unlike CDT, this linear peptide showed much weaker membrane permeabilization activity. Unlike other reported linear analogs (11, 12), in CDT, all four Cys residues are deleted and therefore the spatial arrangements of side chains in CDT could be very different from other analogs. As reported by Rao (12), the side chain structure, folding and its role in peptide-peptide and peptide-membrane interactions could be very important in the design of potent antimicrobial peptides.

Lack of amphipathic structure and hydrophobicity results in poor affinity for cholesterol containing membrane

The fluorescence properties of the intrinsic tryptophan residue of CDT are affected by the presence of negatively charged vesicles, whereas relatively insignificant changes are observed when vesicles of POPC:cholesterol (7:3) mixture were added to the peptide solution (Fig. 3). These data clearly show that CDT does not insert into POPC:cholesterol (7:3) membrane. Previous studies have demonstrated that incorporation of cholesterol imparts rigidity to the membrane and weakens the interaction between the peptide and membrane (28, 51, 52, 65, 66). In our experiments, the absence of an acidic lipid (LPS or PG) and an increase in the membrane rigidity (due to the incorporation of cholesterol) may have limited the binding of CDT to liposomes made of POPC:cholesterol (7:3) mixture. This is consistent with the 31P NMR data, which suggested that the presence of cholesterol reduces the orientational disordering due to the CDT peptide interaction with anionic lipid bilayers (Figure 7). Although the enthalpy of binding of CDT to POPC:cholesterol (7:3) vesicles (Table 2) suggests some interactions with zwitterionic membranes, the failure of CDT to affect either the pretransition or the main transition of DMPC MLVs even at a high concentration of 7.32 mol%, shows that the peptide does not perturb zwitterionic membranes significantly. Taken together, the inability of CDT to insert into POPC:cholesterol (7:3) vesicles (Figures 3A and 3B), the low binding enthalpy observed for these vesicles (Table 2), the inability to affect the phase transition behavior of DMPC (Fig. 5A), and the reduced hydrophobicity due to the deletion of cysteine residues are in agreement with the peptide’s inability to induce hemolysis of erythrocytes whose membrane is rich in zwitterinonic lipids and cholesterol (67).

Tachyplesin I adopts a β-sheet structure in aqueous medium and also upon association with membranes (6-8). As CDT lacks cysteine residues, the peptide is likely to adopt a less ordered or random conformation. The conformational preferences of CDT in aqueous buffer and in the presence of neutral and acidic liposomes were investigated to determine the membrane bound conformation of the peptide. Predictably, CDT exhibits an unordered conformation in aqueous buffer but folds into a more ordered structure in trifluoroethanol (Fig. 6, trace 3) and upon binding to POPC:LPS (61:1) vesicles (Fig. 6, trace 4). Even though CDT retains the amino acids that form the central β-turn segment of tachyplesin I, considering the length of the peptide and distribution of hydrophobic and charged residues, we predict that the peptide would adopt a combination of extended and β-sheet structures upon binding to membranes. Coupled with the observation that CDT induces lipid aggregation in POPC:POPG (7:3) and POPE:POPG (7:3) vesicles, the differences in the CD curves of CDT in the presence of acidic and neutral liposomes can be attributed to the differences in the mode of interaction of the peptide with these membranes (see also Fig. 2). In addition, the structural folding of the peptide, particularly the side chains of residues, could play a role in this selectivity as mentioned above.

While the peptide has the ability to fold into a relatively more ordered β-structure upon binding to negatively charged membranes, it fails to form any ordered structure in the presence of POPC:cholesterol (7:3) vesicles. Since CDT retains the central β-turn segment, the negatively charged vesicles can possibly induce conformational transitions in the N-and C-terminal segments of the peptide in a manner to enhance the amphipathicity of the peptide; this would enable the peptide to effectively interact with the negatively charged and, possibly, bacterial membranes. On the other hand, the absence of an ordered structure for CDT, as observed in the case of POPC:cholesterol (7:3) vesicles, could reduce the amphipathicity and the ability of the peptide to interact with neutral and erythrocyte membranes. These possibilities are reflected in the observed binding affinities, enthalpy of binding and enthalpies of phase transitions for the CDT-membrane interactions.

Growing evidence indicate a strong correlation between biological activity and amphipathic structure and net charge. However, several studies on model peptides (47, 49, 69-70) aimed at identifying the molecular determinants for selectivity in biological activities (antimicrobial vs. hemolytic) show that a lack of or a reduction in α-helical structure results in low hemolytic activity without any significant loss in antimicrobial activity. Similarly, lack of β-structure has been ascribed to the low hemolytic activity of of gramicidin S analogs (49). Therefore, in the case of cationic antimicrobial peptides, lack of amphipathicity due to the disruption of secondary structure may reduce or eliminate the hemolytic activity. On the other hand, the absence of disulfide bonds could make the linear analogs amenable for proteolytic degradation. In this context the use of D amino acids in the peptide design could be important (47, 50). In addition, hydrophobicity, distribution pattern of amino acids, and the folding/interactions of side chains of residues along the peptide chain may also modulate membrane specificity. We believe that the findings presented in this report would be useful in designing peptide antibiotics to target bacterial membrane components such as the LPS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Kazutoshi Yamamoto and Dong-Kuk Lee for help with NMR experiments, and Ulli Duerr and Sudheendra for help in preparing Figures. We would also like to thank Dr. Robert E. W. Hancock for providing LPS-H458 (isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain H458).

Abbreviations

- ANS

1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid

- CD

circular dichroism

- CHL

cholesterol

- CDT

cysteine deleted tachyplesin

- CSA

chemical shift anisotropy

- DMPC

1,2-dimyristoyl- sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine

- DMPG

1,2-dimyristoyl- sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- HEPES

(N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N’-[2-ethanesulfonic acid])

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- MAS

magic angle spinning

- MIC

minimal inhibitory concentration

- MLVs

multilamellar vesicles

- MRSA

multidrug resistant staphylococcus aureus

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine

- POPE

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SUV

small unilamellar vesicle

- TP-I

tachyplesin I

- Tris

tris hydroxymethylaminoethane.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the research funds from National Institutes of Health (AI054515 and DE11117).

REFERENCES

- 1.Nakamura T, Furunaka H, Miyata T, Tokunaga F, Muta T, Iwanaga S, Niwa M, Takao T, Shimonishi Y. Tachyplesin, a class of antimicrobial peptide from the hemocytes of the horseshoe crab (Tachypleus tridentatus): Isolation and chemical structure. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:16709–16713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyata T, Tokunaga F, Yoneya T, Yoshikawa K, Iwanaga S, Niwa M, Takao T, Shimonishi Y. Antimicrobial peptides, isolated from horseshoe crab hemocytes, tachyplesin II, and polyphemusins I and II: chemical structures and biological activity. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 1989;106:663–668. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohta M, Ito H, Masuda K, Tanaka S, Arakawa Y, Wacharotayankun R, Kato N. Mechanisms of antibacterial action of tachyplesins and polyphemusins, a group of antimicrobial peptides isolated from horseshoe crab hemocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1460–1465. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yonezawa A, Kuwahara J, Fujii N, Sugiura Y. Binding of tachyplesin I to DNA revealed by footprinting analysis: Significant contribution of secondary structure to DNA binding and implication for biological action. Biochemistry. 1992;31:2998–3004. doi: 10.1021/bi00126a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuzaki K, Fukui M, Fujii N, Miyajima K. Interactions of an antimicrobial peptide, tachyplesin I, with lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1070:259–264. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawano K, Yoneya T, Miyata T, Yoshikawa K, Tokunaga F, Terada Y, Iwanaga S. Antimicrobial peptide, tachyplesin I, isolated from hemocytes of the horseshoe crab (Tachypleus tridentatus): NMR determination of the beta-sheet structure. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:15365–15367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamamura H, Kuroda M, Masuda M, Otaka A, Funakoshi S, Nakashima H, Yamamoto N, Waki M, Matzumoto A, Lancelin JM, Kohda D, Tate S, Inagaki F, Fujii N. A comparative study of the solution structures of tachyplesin I and a novel anti-HIV synthetic peptide, T22 ([Tyr5,12, Lys7]-polyphemusin II), determined by nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1163:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90183-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laederach A, Andreotti AH, Fulton DB. Solution and Micelle-Bound Structures of Tachyplesin I and Its Active Aromatic Linear Derivatives. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12359–12368. doi: 10.1021/bi026185z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park NG, Lee S, Oishi O, Aoyagi H, Iwanaga S, Yamashita S, Ohno M. Conformation of tachyplesin I from Tachypleus tridentatus when interacting with lipid matrixes. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12241–12247. doi: 10.1021/bi00163a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamamura H, Ikoma R, Niwa M, Funakoshi S, Murakami T, Fujii N. Antimicrobial activity and conformation of Tachyplesin I and its analogs. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1993;41:978–980. doi: 10.1248/cpb.41.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuzaki K, Yoneyama S, Fujii N, Miyajima K, Yamada K-I, Kirino Y, Anzai K. Membrane Permeabilization Mechanisms of a Cyclic Antimicrobial Peptide, Tachyplesin I, and Its Linear Analog. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9799–9809. doi: 10.1021/bi970588v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao AG. Conformation and Antimicrobial Activity of Linear Derivatives of Tachyplesin Lacking Disulfide Bonds. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;361:127–134. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuzaki K, Nakayama M, Fukui M, Otaka A, Funakoshi S, Fujii N, Bessho K, Miyajima K. Role of disulfide linkages in tachyplesin-lipid interactions. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11704–11710. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shai Y. From Innate Immunity to de-Novo Designed Antimicrobial Peptides. Curr. Pharm. Design. 2002;8:715–725. doi: 10.2174/1381612023395367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapaport D, Shai Y. Interaction of fluorescently labeled pardaxin and its analogues with lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:23769–23775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beshiaschvili G, Seelig J. Melittin binding to mixed phosphatidylglycerol /phosphatidylcholine membranes. Biochemistry. 1990;29:52–58. doi: 10.1021/bi00453a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizzo V, Stankowsky S, Schwarz G. Alamethicin incorporation in lipid bilayers: a thermodynamic study. Biochemistry. 1987;26:2751–2759. doi: 10.1021/bi00384a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thennarasu S, Lee D-K, Tan A, Prasad Kari U, Ramamoorthy A. Antimicrobial Activity and Membrane Selective Interactions of a Synthetic Lipopeptide MSI-843. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1711:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hallock KJ, Wilderman KAH, Lee DK, Ramamoorthy A. An innovative procedure using a sublimable solid to align lipid bilayers for solid-state NMR studies. Biophys J. 2002;82:2499–2503. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75592-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Washburn EW, West CJ, Hull C. International Critical, Tables of Numerical Data, Physics, Chemistry, and Technology. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett AE, Rienstra CM, Auger M, Lakshmi KV, Griffin RG. Heteronuclear decoupling in rotating solids. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:6951–6958. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slavik J. Anilinonaphthalene sulfonate as a probe of membrane composition and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;694:1–25. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(82)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao D, Wallace BA. Differential light scattering and absorption flattening optical effects are minimal in the circular dichroism spectra of small unilamellar vesicles. Biochemistry. 1984;23:2667–2673. doi: 10.1021/bi00307a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jing W, Hunter NH, Hagel J, Vogel HJ. The structure of the antimicrobial peptide Ac-RRWWRF-NH2 bound to micelles and its interactions with phospholipid bilayers. J. Peptide Res. 2003;61:219–229. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2003.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinia HA, Boots JW, Rijkers DT, Kik RA, Snel MM, Demel RA, Killian JA, Der Eerden JP, de Kruijff B. Domain formation in phosphotidylcholine bilayers containing transmembrane peptides: specific effects of flanking residues. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2814–2824. doi: 10.1021/bi011796x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rojo N, Gómara MJ, Busquets MA, Alsina MA, Haro I. Interaction of E2 and NS3 synthetic peptides of GB virus C/Hepatitis G virus with model membranes. Talanta. 2003;60:395–404. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(03)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poon A, Thennarasu S, Lee D-K, Kawulka KE, Vederas JC, Ramamoorthy A. Membrane Permeabilization, Orientation, and Antimicrobial Mechanism of Subtilosin A. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henzler-Wildman KA, Martinez GV, Brown MF, Ramamoorthy A. Perturbation of the Hydrophobic Core of Lipid Bilayers by the Human Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8459–8469. doi: 10.1021/bi036284s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blanco F, Ramirez-Alvendo M, Serrano L. Formation and stability of β-hairpin structures in polypeptides. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1998;8:107–111. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trudelle Y. Conformational study of the sequential (Tyr-Glu)n copolymer in aqueous solution. Polymer. 1975;16:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirakura Y, Kobayashi S, Matsuzaki K. Specific interactions of the antimicrobial peptide cyclic β-sheet tachyplesin I with lipopolysaccharides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1562:32–36. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scherer PG, Seelig J. Electric charge effects on phospholipids headgroups. Phosphatidylcholine in mixtures with cationic and anionic amphiphiles. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7720–7728. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seelig J, Seelig A. Lipid conformation in model membrane and biological membranes. Q Rev Biophys. 1980;13:19–61. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picard F, Paquet M-J, Lévesque J, Bélanger A, Auger M. 31P NMR first spectral moment study of the partial magnetic orientation of phospholipid membranes. Biophys J. 1999;77:888–902. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76940-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santos JS, Lee DK, Ramamoorthy A. Effects of Antidepressants on the Conformation of Phospholipid Headgroups Studied by Solid-State NMR. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2004;42:105–114. doi: 10.1002/mrc.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindstrom F, Williamson PTF, Grobner G. Molecular insight into the electrostatic membrane surface potential by 14N/31P MAS NMR spectroscopy: Nociceptin-lipid association. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6610–6618. doi: 10.1021/ja042325b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu JX, Damodaran K, Blazyk J, Lorigan GA. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation studies of the interaction mechanism of antimicrobial peptides with phospholipid bilayer membranes. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10208–10217. doi: 10.1021/bi050730p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Satoh K, Okuda H, Horimoto H, Kodama H, Kondo M. Synthesis and properties of a heterodetic cyclic peptide: Gramicidin S analog containing disulfide bond. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1990;63:3467–3472. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamamura H, Ikoma R, Niwa M, Funakoshi S, Murakami T, Fujii N. Antimicrobial activity and conformation of Tachyplesin I and its analogs. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1993;41:978–980. doi: 10.1248/cpb.41.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shai Y. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by α-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1462:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandenburg K, Wiese A. Endotoxins: Relationships between Structure, Function, and Activity. Curr. Topics Med. Chem. 2004;11:1127–1146. doi: 10.2174/1568026043388213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jerala R, Porro M. Endotoxin Neutralizing Peptides. Curr. Topics Med. Chem. 2004;11:1173–1184. doi: 10.2174/1568026043388079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott MG, Gold MR, Hancock REW. Interaction of Cationic Peptides with Lipoteichoic Acid and Gram-Positive Bacteria. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:6445–6453. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6445-6453.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson RC, Hancock REW, Yu P-L. Antimicrobial Activity and Bacterial-Membrane Interaction of Ovine-Derived Cathelicidins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:673–676. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.2.673-676.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuzaki K. Why and how are peptide-lipid interactions utilized for self-defense? Magainins and tachyplesins as archetypes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1462:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wildman KAH, Lee DK, Ramamoorthy A. Mechanism of Lipid Bilayer Disruption by the Human Antimicrobial Peptide, LL-37. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6545–6558. doi: 10.1021/bi0273563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oren Z, Hong J, Shai Y. A Repertoire of Novel Antibacterial Diastereomeric Peptides with Selective Cytolytic Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:14643–14649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuzaki M, Sugishita K, Fujii N, Miyajima K. Molecular Basis for Membrane Selectivity of an Antimicrobial Peptide, Magainin 2. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3423–3429. doi: 10.1021/bi00010a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kondejewski LH, Farmer SW, Wishart DS, Kay CM, Hancock REW, Hodges RS. Modulation of Structure and Antibacterial and Hemolytic Activity by Ring Size in Cyclic Gramicidin S Analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:25261–25268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong J, Oren Z, Shai Y. Structure and organization of hemolytic and nonhemolytic diastereomers of antimicrobial peptides in membranes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16963–16973. doi: 10.1021/bi991850y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cullis PR, van Dijck PWM, de Kruijff B, de Gier J. Effects of cholesterol on the properties of equimolar mixtures of synthetic phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine: A 31P NMR and differential scanning calorimetry study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;513:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90108-6. J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hallock KJ, Lee D-K, Omnaas J, Mosberg HI, Ramamoorthy A. Membrane Composition Determines Pardaxin’s Mechanism of Lipid Bilayer Disruption. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1004–1013. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75226-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Epand RM, Sayer BG, Epand RF. Peptide-induced formation of cholesterol-rich domains. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14677–14689. doi: 10.1021/bi035587j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown MF, Seelig J. Nature. 1977;269:721–723. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dave PC, Billington E, Pan YL, Straus SK. Interaction of alamethicin with ether-linked phospholipid bilayers: Oriented circular dichroism, P-31 solid-state NMR, and differential scanning calorimetry studies. Biophys. J. 2005;89:2434–2442. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strandberg E, Ulrich AS. NMR methods for studying membrane-active antimicrobial peptides. Concep. Magn. Reson. 2004;23:89–120. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powers JPS, Tan A, Ramamoorthy A, Hancock REW. Solution Structure and Interaction of the Antimicrobial Polyphemusins with Lipid Membranes. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15504–15513. doi: 10.1021/bi051302m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hallock KJ, Lee DK, Ramamoorthy A. MSI-78, an analogue of the magainin antimicrobial peptides, disrupts lipid bilayer structure via positive curvature strain. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3052–60. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marcotte I, Wegener KL, Lam YH, Chia BCS, de Planque MRR, Bowie JH, Auger M, Separovic F. Interaction of antimicrobial peptides from Australian amphibians with lipid membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2003;122:107–120. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mani R, Buffy JJ, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI, Hong M. Solid-state NMR investigation of the selective disruption of lipid membranes by protegrin-1. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13839–13848. doi: 10.1021/bi048650t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mani R, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI, Hong M. Membrane-disruptive abilities of beta-hairpin antimicrobial peptides correlate with conformation and activity: A P-31 and H-1 NMR study. BBA-Biomembranes. 2005;1716:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abu-Baker S, Qi XY, Newstadt J, Lorigan GA. Structural changes in a binary mixed phospholipid bilayer of DOPG and DOPS upon saposin C interaction at acidic pH utilizing P-31 and H-2 solid-state NMR spectroscopy. BBA-Biomembranes. 2005;1717:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Porcelli F, Buck B, Lee DK, Hallock KJ, Ramamoorthy A, Veglia G. Structure and Orientation of Pardaxin Determined by NMR Experiments in Model Membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:45815–45823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405454200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mecke A, Lee DK, Ramamoorthy A, Orr BG, Holl MMB. Membrane thinning due to antimicrobial peptide binding: An atomic force microscopy study of MSI-78 in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2005;99:4043–4050. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dempsey CE, Ueno S, Avison MB. Enhanced membrane permeabilization and antibacterial activity of a disulfide-dimerized magainin analogue. Biochemistry. 2003;42:402–9. doi: 10.1021/bi026328h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Epand RF, Ramamoorthy A, Epand RM. Membrane lipid composition and the interaction with Pardaxin: the role of cholesterol. Prot. Pept. Lett. 2006;13:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zwaal RF, Schroit AJ. Pathophysiologic Implications of Membrane Phospholipid Asymmetry in Blood Cells. Blood. 1997;89:1121–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tachi T, Epand RF, Epand RM, Matsuzaki K. Position-Dependent Hydrophobicity of the Antimicrobial Magainin Peptide Affects the Mode of Peptide-Lipid Interactions and Selective Toxicity. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10723–31. doi: 10.1021/bi0256983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dathe M, Wieprecht T, Nikolenko H, Handel L, Maloy WL, MacDonald DL, Beyermann M, Bienert M. Hydrophobicity, hydrophobic moment and angle subtended by charged residues modulate antibacterial and haemolytic activity of amphipathic helical peptides. FEBS Lett. 1997;403:208–212. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maloy WL, Kari UP. Structure-activity studies on magainins and other host defense peptides. Biopolymers. 1995;37:105–122. doi: 10.1002/bip.360370206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]