Abstract

Policies relating to contraceptive services (population, family planning and reproductive health policies) often receive weak or fluctuating levels of commitment from national policy elites in Southern countries, leading to slow policy evolution and undermining implementation. This is true of Kenya, despite the government's early progress in committing to population and reproductive health policies, and its success in implementing them during the 1980s. This key informant study on family planning policy in Kenya found that policy space contracted, and then began to expand, because of shifts in contextual factors, and because of the actions of different actors. Policy space contracted during the mid-1990s in the context of weakening prioritization of reproductive health in national and international policy agendas, undermining access to contraceptive services and contributing to the stalling of the country's fertility rates. However, during the mid-2000s, champions of family planning within the Kenyan Government bureaucracy played an important role in expanding the policy space through both public and hidden advocacy activities. The case study demonstrates that policy space analysis can provide useful insights into the dynamics of routine policy and programme evolution and the challenge of sustaining support for issues even after they have reached the policy agenda.

Keywords: Policy analysis, family planning, health policy, contraception

KEY MESSAGES.

Policy space for the issue of family planning in Kenya contracted during the late 1990s, and has since begun to expand, due to changing contextual factors and the actions of different individuals.

Proponents of family planning within two government ministries played an important role in expanding the policy space through both public and intra-government advocacy activities.

Policy space analysis can provide useful insights into the dynamics of routine policy and programme evolution and the challenge of sustaining support for issues after they have made it onto the policy agenda.

Introduction

In many parts of the world policies relating to contraceptives tend to receive weak or fluctuating levels of commitment from national policy elites, leading to slow policy evolution and undermining implementation. This is true of Kenya, where the government made early progress in committing to population policies during the 1960s and in contraceptive service provision during the 1970s and 1980s, yet where resource allocations and implementation subsequently declined (Chimbwete and Zulu 2003). In Kenya, as elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, the past decade has seen a weakening prioritization of contraceptive programmes in national and international policy agendas (Cleland et al. 2006), undermining access to services and progress towards the Millennium Development Goals.

This key informant study examines factors affecting the fluctuating level of prioritization of contraceptive service provision among Kenyan government policy-makers since the mid-1990s. Contraceptive services are usually referred to as ‘family planning’ in national policy debates in Kenya and are framed as cutting across reproductive health and population concerns (Ministry of Health 2000, 2007; NCPD 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006a). Based on key informant interviews and a review of academic and official publications and reports, the paper focuses on the strategies and actions taken by a range of actors to ‘reposition’ family planning in government policy and to ensure the incorporation of contraceptive commodities in the national government budget of 2005, for the first time in the country's history.

The problem of sustaining political and bureaucratic commitment for the implementation and evolution of policies affects a variety of policy issues (Grindle and Thomas 1991; Buse et al. 2005). Waning commitment can lead to stagnation in implementation, and can undermine the likelihood that political and bureaucratic actors create new policies and strategies to adapt to changing contexts, such as shifts in external funding trends. In Southern countries and elsewhere, reproductive health policies are particularly vulnerable to weak political commitment, because they do not tend to have strong national support bases and have historically been controversial and perceived as driven by external actors (Jain 1998; Chimbwete and Zulu 2003). Thomas and Grindle (1994), in their review of population reforms in 16 countries, explain that sustained commitment to the implementation of population policies tends to be constrained by two main factors: the dispersed and long-term nature of their impacts, and the lack of mobilized support from users of contraceptive services. Reproductive health and population policies have therefore been vulnerable to deprioritization and neglect in many Southern countries, especially in the context of the shift in international attention and official development assistance to HIV and AIDS programmes during the 1990s (Cleland et al. 2006).

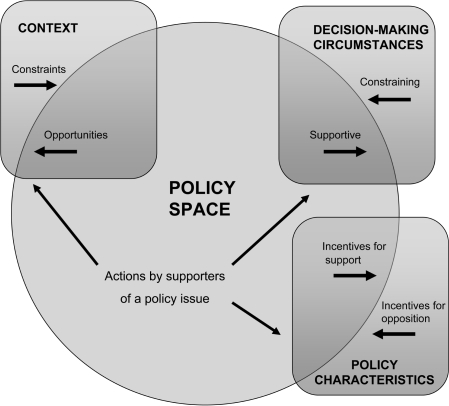

In this paper, I contend that policy space analysis provides a useful framework for understanding why commitment to existing policies often fluctuates over time, and for mapping the room for manoeuvre that advocates of particular policies have for addressing policies that are being neglected. Policy elites can be thought of as operating within a ‘policy space’, which influences the degree of agency they have for reforming and driving policy implementation, but which can be expanded by the exercise of that agency. These concepts are drawn from Grindle and Thomas (1991), who suggest that the scope of policy space is influenced by the way in which policy elites manage the interactions between (1) national and international contextual factors, (2) the circumstances surrounding the policy process, and (3) the acceptability of the policy's content. Figure 1 represents policy space as a balloon, which can be expanded, constrained or contracted by shifts in these factors and by peoples' actions.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting policy space

Firstly, contextual factors are the pre-existing circumstances within which policy processes occur. They can act as opportunities and constraints for policy elites’ prioritization of a policy issue, and include historical, social, cultural, political, economic and demographic characteristics of a country and situational or focusing events, like epidemics, droughts or media coverage of issues (Kingdon 1984; Grindle and Thomas 1991). Policy-makers are confronted with a multitude of competing issues and have limited resources for dealing with them (Shiffman 2007). External actors and international structural trends have a critical influence on national health policy processes, with increasing diversity and fragmentation of international actors and sources of funding (Walt and Buse 2000; Cerny 2002). These international factors often have contradictory influences, particularly in contexts characterized by national government dependence on external funds, aid conditionalities, shifting funding priorities, and persistence in vertical programming (Walt and Buse 2000; Cerny 2002; Mayhew et al. 2005). The background characteristics of policy elites are also important pre-existing factors that shape policy space; for example the values, level of expertise, experience, degree of influence and loyalties of elites influence both their receptiveness to policy change, and their success in championing particular policies.

A second area affecting policy space is that of ‘policy circumstances’, or the ways in which policy makers’ perceptions about a policy issue shape the dynamics of decision making. The extent to which a policy issue is perceived by policy elites to be a matter of crisis or ‘politics-as-usual’ affects the level at which decisions are taken, the urgency with which decisions are made, and the extent of risk taking (Grindle and Thomas 1991; Walt and Gilson 1994). Policy crises involve strong pressure on policy makers to act, as well as high political stakes, and can lead to radical shifts in the prioritization of issues. When policies are not perceived as urgent, decision making may be dominated by concerns about micropolitical and bureaucratic costs and benefits. Policy circumstances differ from contextual factors because of their dynamic element:

How particular circumstances are perceived by policy elites […] serves as a bridge between the “embedded orientations” of individuals and societies and the kinds of changes considered by decision makers confronted with specific policy choices. (Thomas and Grindle 1994, p.53)

Lastly, the policy's characteristics are themselves influenced by policy elites’ decisions, but also affect the scope policy makers have for introducing a policy and prioritizing it. The acceptability of a policy is influenced by policy characteristics such as the distribution of the costs and benefits associated with its implementation across policy actors and society, which in turn affects the level of support or opposition to the policy from various stakeholders (Kingdon 1984). Characteristics of a policy that affect its acceptability include its implications for vested interests, the level of public participation it involves, the resources required for implementation and the length of time needed for its impacts to become visible (Grindle and Thomas 1991).

In Grindle and Thomas’ model, the various factors interrelate in the following ways. Contextual factors shape the circumstances of decision making by policy elites concerning particular policies at particular times. These decisions in turn shape the characteristics of the policy, and public and bureaucratic incentives to support or oppose it. These incentives in turn shape decisions by policy makers and policy managers about resource allocation, and explain how prioritization and implementation may fluctuate over time. Though the framework was initially developed for analysing processes of agenda setting, decision-making circumstances directly affect policy makers’ and managers’ decisions about subsequent implementation, for example where shifts in perceptions of the issue among policy elites affect decisions about resource allocation. Importantly, as Figure 1 illustrates, policy makers can widen the policy space they operate within by taking actions to influence the different factors, for example by building consensus or by forming coalitions in support of an issue.

Indeed, analysis of agenda setting across different contexts shows that individual politicians and bureaucrats often play a central role in championing issues and getting them onto the policy agenda, in addition to non-government advocates (Grindle and Thomas 1991; Shiffman 2007). Such analyses also show that the level of success of advocacy initiatives depends on a combination of factors including: clear indicators to show the extent of the problem, the presence of political entrepreneurs to champion the cause, and the organization of attention-generating focusing events; as well as the political acceptability of policies (Shiffman 2007). Successful advocacy may also require the ‘framing’ of contested or neglected issues in a way that legitimizes them as an important issue for governments to address (Schön and Rein 1991; Joachim 2003), appealing to prevailing social norms (Shiffman 2007) and employing policy narratives, or stories, that simplify issues and persuade others of their importance (Roe 1991; Keeley 2001). This case study has implications for government and non-governmental advocates aiming to sustain commitment to existing policies in shifting national and international contexts, particularly policies relating to contraceptive services and other neglected sexual and reproductive health issues.

Methods

The material for this case study is based on 13 semi-structured interviews and three unstructured discussions carried out during 2006 and 2007 with high-level officials and programme staff from government ministries and agencies, international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), national NGOs, a bilateral donor and an academic with expertise in demography in Kenya.1 Interviews were recorded in shorthand during the interview and then typed up by the interviewer immediately afterwards. The notation I1, I2, IX is used in the results section as a code for the various key informants. I also reviewed official and academic publications and grey material on family planning policy in Kenya, reports of relevant meetings, and the theoretical literature on budget and policy processes.

I investigated the factors affecting the policy space for reform using the framework developed by Grindle and Thomas (1991). I also carried out textual analysis (Ulin et al. 2005) of interview transcripts to gain insights into the experiences of the different individuals who played key roles in the policy process, and the narratives they used to explain the importance of family planning as a policy issue.

While carrying out the analysis, I compared and triangulated data from different key informant interview transcripts with written resources to assess their validity and to mitigate the impact of biased or partial testimony from key informants. Where discrepancies and information gaps were found, I carried out further investigation through telephone interviews with key informants and grey literature investigations, to resolve inconsistencies and address omissions.

Results

This section begins with an overview of family planning policy in Kenya. The remainder of the section examines each of the factors affecting the policy space for family planning, analysing the ways in which they helped to expand or contract policy space.

Box 1 summarizes Kenya's long history of population and reproductive health programmes. The first Population Policy was introduced in 1967, however government involvement in contraceptive service provision did not begin in earnest until the 1980s (Chimbwete and Zulu 2003). During the 1980s and early 1990s, the Kenyan government demonstrated considerable commitment to family planning, through the development of national policies and guidelines, involvement of high-level politicians, the establishment of the National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) in the Office of the Vice President, and support for increased distribution of contraceptives through governmental and non-governmental health facilities, and extensive information, education and communication (IEC) campaigns (Ajayi and Kekovole 1999; Blacker 2006). Service provision expanded impressively during this period, and the contraceptive prevalence rate in Kenya increased from 7 to 27% between 1980 and 1989 (Ajayi and Kekovole 1999).

Box 1 The history of family planning policy and programmes in Kenya.

| 1962 | Family Planning Association of Kenya (FPAK) established |

| 1967 | Government of Kenya's first population policy, but contraceptive services and Information, Education and Communication (IEC) mainly provided by the private sector |

| 1975 | The government launched a 5 year Family Planning Programme |

| 1982 | The National Council for Population and Development was established in the Office of the Vice President |

| 1984 | First National leader's Population Conference in Nairobi |

| 1994 | United Nations International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), Cairo |

| 1996 | NCPD published its National Population Advocacy and IEC Strategy for Sustainable Development 1996–2010 |

| 1997 | National Reproductive Health Strategy published |

| 2000 | NCPD published the second Population Policy for Sustainable Development |

| 2003 | Kenya Demographic and Health Survey generates deteriorating indicators (published in 2004) |

| 2004 | NCPD became a semi-autonomous agency under the Ministry of Planning and Economic Development, the National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development (NCAPD) |

| 2005 | The budget for 2005/6 presented to parliament and passed, allocating Kenyan government funds to family planning for the first time |

| 2007 | National Reproductive Health Policy published |

International factors played a leading role in this original expansion of policy space for family planning, with external actors advocating for and supporting the implementation of the population policy. At this time, donors covered the costs of all government and non-government contraceptives and IEC campaigns. During the second half of the 1990s, however, external funding for services and IEC declined, in the context of a shift in priorities to HIV and AIDS and donor fatigue (Aloo-Obunga 2003; NCPD 2003; I5; I13).

The Kenyan government was slow to respond to the shifting international aid allocations. Combined with poor management of commodity procurement between the Ministry of Health and the Kenya Medical Supplies Agency (KEMSA)2 (I13; I4), the unreliable and dwindling international funds were a cause of a considerable weakening of government and voluntary sector contraceptive services (I2; I7; I4). In 1996, the NCPD launched a National Population Advocacy and IEC strategy for Sustainable Development 1996–2010, but this strategy floundered when funding from UNFPA was withdrawn in 2000 (I5; I6; The Global Gag Rule Project 2006). Some clinics suffered from commodity stock outs and lack of method choice during the early 2000s, while others closed altogether (I2; I4; I7). The Kenya Service Provision Assessment Survey of 2004 found that in the 5 years preceding the survey, the proportion of health facilities offering any method of family planning declined from 88 to 75% (NCAPD et al. 2005).

The 2003 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) results revealed a stall in fertility decline at 4.8 in 1998–2003, and the rate actually rose for women who had not completed primary education (Blacker et al. 2005; CBS et al. 2005; Westoff and Cross 2006). The 2003 KDHS revealed increases in unmet need for contraception and high contraception discontinuation rates (Blacker et al. 2005). These trends caused concern among national and international actors about the implications for the rate of population growth in Kenya.3 In 2004, UN predictions of Kenya's population by mid-2050 were revised from 48 to 70 million, based on these new figures (Cleland et al. 2006).

Various societal, economic and demographic factors may have contributed to the worsening fertility and contraceptive use trends, and there are differences of opinion among analysts about the impact of declining donor resource allocations for contraceptives and weakening service delivery (Blacker et al. 2005; Bongaarts 2005; Westoff and Cross 2006). But in any case, the new data provided powerful evidence for reproductive health proponents, and catalysed a series of advocacy initiatives with the aim of influencing the government to prioritize contraceptive services and allocate public funding to contraceptive commodities. The advocacy initiatives included meetings with parliamentarians and informal advocacy in government budget meetings. A line item for contraceptive commodities was eventually included in the 2005 national budget, allocating 200 million Kenyan Shillings, or US$2.62 million.4

The new budget line signifies a widening of policy space after its contraction in the 1990s. Advocates had mobilized concern among key decision-makers about the KDHS 2003 results and as a result of these efforts, government funds were allocated to contraceptives for the first time in Kenya's history. The incorporation of contraceptive programmes into the national budget demonstrates national commitment (Shiffman 2006), and enhances the potential for sustaining public programmes in the face of potential fluctuations in external funding. The government allocation for this line increased to 300 million Kenyan shillings, or US$4.17 million, in the 2006/7 budget.4 However, it should be noted that this is still only around one-third of the cost of Kenya's public sector provision of family planning commodities according to 2000 projections (Ministry of Health 2003), and proponents of family planning continue to seek public funding from increased national allocations and from devolved government funds.

Factors affecting policy space

This section examines how policy elites interacted with each of the three sets of factors in the policy space framework, to assess how each influenced the contraction and expansion of policy space over time, ultimately leading to the inclusion of contraceptive commodities in Kenya's 2005 budget. Table 1 summarizes contextual factors, policy circumstances and policy characteristics, comparing their impact on policy space during the second half of the 1990s with the years since 2000.

Table 1.

Factors affecting policy space for family planning in Kenya

| Mid to late 1990s, Policy space contracting | Early 2000s, Policy space expanding | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Contextual factors | ||

| Influences on policy elites | ↓ Lack of response to negative donor funding trends by high-level politicians | ↑ Religious opposition becoming less vocal |

| ↓ Religious opposition to contraceptives | ||

| ↑ Government consensus building with religious groups | ||

| Change of government in 2002 | ↓ Shortage of government resources allocated to health sector | ↑ New government increasing resources to the health sector |

| ↑ Passive support from high-level politicians | ||

| Bureaucratic | ↓ Conservative budget officials | ↑ Mandate and influence of NCAPD |

| ↓ Intra- and inter-sectoral competition for resources | ↑ Concern about weak service delivery within Ministry of Health | |

| ↓ Conservative budget officials | ||

| ↓ Intra- and inter-sectoral competition for resources | ||

| ↑ Introduction of the MTEF | ||

| International | ↓ Vertical HIV and AIDS funding ↓ Prioritization of HIV and AIDS ↓ Reduced donor funding for contraceptive services and IEC | ↑ Financial and technical support for family planning advocacy from international NGOs and donors |

| Availability of policy evidence | ↑ Availability of new evidence of a decline in family planning | |

| 2. Policy circumstances | ↓ HIV and AIDS became a policy crisis, drawing attention and funding away from family planning | ↑ HIV and AIDS policy is making a gradual transition from ‘crisis’ policy making to ‘politics-as-usual’ |

| 3. Policy characteristics | ↓ Lack of mobilized support from users of contraceptive services | ↓ Lack of mobilized support from users of contraceptive services |

| ↓ Some religious sensitivity about contraceptive services | ↑ Decreasing religious sensitivity about contraceptive services | |

| ↓ Vested interests undermining policy implementation | ↓ Vested interests undermining policy implementation |

↓: Factors constraining or contracting policy space.

↑: Factors expanding policy space.

(1) Contextual factors

Changes over time in the political, bureaucratic, national and international context had a major impact on the room for manoeuvre open to proponents of family planning within the bureaucracy. Table 1 shows how, during the mid-2000s, there were shifts in all these areas that either increased opportunities for family planning to be prioritized within government, or reduced the contextual constraints against this occurring. The role played by policy actors in working with these shifts and building on them is outlined in the text, below.

Influences on policy elites

Analysts of the national political environment for family planning policy in Kenya contend that commitment to the issue by policy elites tended to be ambivalent during the 1960s and 1970s, and that this was strongly influenced by contextual factors such as prevailing cultural and religious attitudes. During this period, there was considerable popular opposition to contraceptives and to population control in Kenyan society, especially outside the narrow class of urban ‘modernising elites’ (Ajayi and Kekovole 1999; Chimbwete and Zulu 2003). This included opposition to the use of contraceptives from religious groups and from pro-natalist attitudes associated with tribal politics. During this period, some technocrats were convinced by arguments from the international population control lobby about the beneficial impacts of lowering fertility rates for economic development, but key policy elites expressed scepticism about family planning on cultural, religious and pro-natalist grounds (Ajayi and Kekovole 1999; Chimbwete and Zulu 2003). President Jomo Kenyatta is said to have never fully reconciled contraception with his cultural and religious attitudes, and believed that Kenyan society was too opposed to contraceptives for the government to openly promote them or directly provide services. Instead, he introduced the population policy more to impress and build links with the international community and access international population funding than out of genuine conviction (Chimbwete and Zulu 2003).

During the 1980s, President Daniel Arap Moi appears to have been less troubled than his predecessor by religious and cultural reservations about family planning, which enabled him to take important measures to ensure effective implementation of the population policy. Moi appears to have been more influenced by neo-Malthusian arguments, using them in a number of public statements in support of the issue (Ajayi and Kekovole 1999; Chimbwete and Zulu 2003; Blacker 2006). In addition, concerns about economic stagnation and heightened pressure from donors such as the World Bank also pushed Moi's government into prioritizing family planning (Ajayi and Kekovole 1999; Chimbwete and Zulu 2003). The government-led services and IEC campaigns sparked a backlash from some religious organizations and community leaders, who made public statements of opposition to the policy. However, the government and reproductive health NGOs worked to create a supportive environment for family planning and population policies by sensitizing religious organizations, the public and the media to the issue (I5; I7; I14; I17). When multi-party elections were reintroduced in the early 1990s, all political parties included population issues in their manifestos (Ajayi and Kekovole 1999), demonstrating the success of these campaigns.

However, Moi's commitment had significant limits, as family planning commodities remained totally funded by donors while he was in power, and his government failed to take action in response to declining resource allocations from donors, allowing implementation and policy evolution to stagnate (NCAPD 2003). This lends weight to the assertion by some key informants from donor agencies and NGOs (I14; I16; I17) that policy elites in Kenya had never fully taken ownership of family planning policy, even during the 1980s.

By the 2000s, pro-natalist attitudes appear to have much less influence on Kenyan politicians than in the past (I2; I6; I8; I14; I15; NCAPD 2006a). The influence of organized religious opposition to contraceptives has also considerably decreased (I5; I6; I3; I4; I15). Efforts by the Kenyan government to build consensus with religious groups during the 1990s appear to have helped to reduce the opposition. The 2000 Population Policy was a milestone in this process, with religious coalitions being actively involved in the drafting of the policy before it was adopted in parliament (I5).

The increasing visibility of HIV and AIDS-related illness and mortality over the past decade or so may also have helped to make opposition less vocal. One key informant argued that HIV and AIDS have led religious groups to reconsider their opposition to family planning, especially the use of condoms:

'… no one has not been affected by HIV/AIDS. Religious groups have decided to lay low and remain silent'. (I5)

Although religious organizations continue to influence the government to exercise caution in their policy making in persistently controversial areas such as abortion, emergency contraception and sexuality education, key informants did not consider general family planning policy to be affected by religious opposition. In addition, high-level politicians in the 2002–07 government appear to have strong personal convictions about family planning. President Mwai Kibaki is known to be convinced by economic arguments for limiting population growth (Ajayi and Kekovole 1998; Chimbwete and Zulu 2003), and the ministers of health and finance during that period were considered to be sympathetic to reproductive health issues (I4; I6; I17).

Change of government in 2002

Moi's government failed to address the declining implementation of family planning policy during the 1990s, and it seems that the change of administration in 2002 may have brought an impetus of change that helped to mobilize action to address this issue. The new government may have helped to expand policy space by bringing politicians who were more supportive of family planning into key positions. The arrival of the new government certainly precipitated two actions that indicate high-level sympathy for the issue. These were the creation of the National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development (NCAPD) through an act of parliament in 2004, with its new advocacy mandate, and the issuing of a Cabinet Memorandum tabled by NCAPD in the same year, which called for the government to make renewed efforts in family planning. In addition, one senior official in the Ministry of Health and one donor argued that the change of administration allowed increasing government allocations to the health sector and made it more likely that politicians would take public health issues such as reproductive health more seriously (I13; I17).

Bureaucratic culture, capacity and institutional arrangements

Conservatism, lack of transparency and concentration of decision-making power in the budget process were factors constraining the policy space throughout the period examined. These were significant in preventing the government from allocating resources to contraceptives until 2005. One key informant described budget officers in the ministries of health and finance as being opposed to any display of creativity or decisions that are perceived as ‘radical’ (I6). Budget officials had to be convinced of the need to innovate by introducing government funding for an item that was already funded by donors:

Health indicators such as IMR [infant mortality rates] and MMR [maternal mortality rates] are declining in Kenya. Our strategic plan 2005–2010 shows the need to reverse these trends. FP is important for reducing MMR. One third of IMR is neonatal mortality. Economists understood this. But there was a feeling that partners were already supporting adequately. So why put money to this not drugs or infrastructure? (I4)

However, other bureaucratic factors helped to facilitate the new budget line in 2005. One example is the existence of planning units in each sectoral ministry, which supported the transfer of knowledge, information and skills between the Ministry of Planning and the Ministry of Health. The head of the Planning Unit, who was seconded from the Ministry of Planning, had been involved in the production of the 2003 KDHS, and therefore had a good understanding of population and contraceptive use trends, and a personal stake in the issue (I12). This official was formally responsible for the initial drafting of the Ministry of Health budget. The introduction of the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) in 1999 (Ministry of Health 2005) may also have been a supporting factor. Since the MTEF allows for annual increases in resources for existing budget lines, allocations for family planning were much easier to pass in 2006 than in 2005 (I1; I4; I7; I12; I13).

Since its creation as an agency in 2004, the existence of NCAPD has been an important factor expanding the policy space for family planning prioritization in Kenya. One key informant emphasized that the transformation of the National Council for Population and Development into the agency NCAPD led to a considerable improvement in its effectiveness and policy influence. NCAPD is part of the Ministry of Planning, but is semi-autonomous, so has greater operational flexibility than its predecessor (I1; I7). Unlike the Division of Reproductive Health, NCAPD has a mandate to conduct high-level advocacy (I2; I6, I14; NCAPD 2005). In 2003, shortly before NCPD made its transition to an agency, a new Director was appointed, who was charismatic and influential within government and with donors, enabling him to take advantage of this mandate to mobilize resources for family planning advocacy, and to sell the issue in high-level meetings (I9; I14).

The experience of poor implementation within the Ministry of Health during the late 1990s and early 2000s was also an important factor creating concern about the issue within the ministry and triggering action to address it. In the Division of Reproductive Health and among NGO service providers, the policy problem was identified because of stock outs of family planning commodities from health facilities, leading to a concern that family planning policy implementation was ineffective and action needed to be taken to improve service delivery. One official in the ministry stated that,

The Ministry of Health had a general feeling that FP implementation was not good enough. (I3)

International influences

Population first made it onto the Kenyan government's agenda because of the influence of external actors, and even at the height of prioritization of the issue during the 1980s and early 1990s, the government always relied on external resources to fund policy implementation (Ajayi and Kerkovole 1998; Chimbwete and Zulu 2003). As with the national government, many international donors shifted their priorities to HIV and AIDS during the 1990s, leading to declining foreign aid allocations for family planning (Aloo-Obunga 2003; NCPD 2003). The strong external pressure that had influenced political elites to prioritize population and reproductive health issues during the 1980s and early 1990s declined. In addition, some key informants described a situation of donor fatigue brought on by frustration with poor planning and lack of ownership for family planning in the Ministry of Health.

Donors got fed up with the lack of planning. DRH used to say, “we have a shortage of pills. UNFPA can give us an emergency drop”. UNFPA would do this, but 6 months later they’d come back and ask for another bail out. (I14)

Some key informants stated that donor agencies consider IEC to be expensive and lack conviction in its importance and effectiveness (I6; I2). There appears to have been complacency among donors as well as national actors about fertility transition, and a belief that it would happen naturally without the need for sustained interventions.

Implementation disappeared in the 1990s. There was an expectation that the transition would continue automatically. Resources were moved away. (I1)

Donors no longer wanted to support community-based distribution, questioning its impact. (I2)

Government and donor key informants unsurprisingly differed as to where they put the blame for poor coordination and commodity stockouts, with a USAID official stating that:

[…] there was a major problem when the Germans picked up the bulk of procurement, but there was a 6 month gap between projects which the ministry had not picked up on, so there were almost commodity stockouts. The ministry did not understand the donor's cycle. (I14)

A senior government official on the other hand, argued,

Donors have no idea of our procurement schedule. You would find lorries arriving at KEMSA without any storage space. (I13)

While external assistance for service delivery and IEC has dropped, international actors have increased their support to ‘behind the scenes’ advocacy campaigns to reposition family planning. This includes the provision of financial and technical assistance for advocacy on family planning from donors such as USAID, and of technical assistance from international NGOs such as the Futures Group and the African Population and Health Research Center (I2; I14). Since 2000, UNFPA has been funding improvements in the division of responsibility and coordination between the Ministry of Health and NCAPD, which may have helped them to carry out joint advocacy for family planning (I5). In the past few years, some donors have been working with the Ministry to strengthen procurement policy, though it is too early to assess the impacts of these efforts (I6; I14). A key shift in international engagement between the 1980s and recent years is, therefore, that external actors are now trying to create local ownership for family planning by supporting national advocates of the issue, particularly government officials and parliamentarians.

Availability of policy evidence

The availability of new data in 2003 demonstrating that a ‘policy problem’ existed was a catalyst for alerting policy entrepreneurs to the need for family planning to be reprioritized. Key informants from the NCAPD, Ministry of Health, USAID and NGOs pointed to the importance of the 2003 KDHS data in identifying and persuading others about the importance of the issue.

The plateau [of contraceptive use and fertility rates] was a critical turning point. (I1)

The results showed clearly that unmet need for FP had not changed for over 10 years. Contraceptive prevalence was the same. The TFR was beginning to show an increase. These figures rang a bell. So we did further analysis. Our finding was that there was a shortage of commodities. […] We needed a broad program of high-level advocacy to lobby government, partners and donors. (I2)

Contrary to the previous quotation, those working on the issue in government had already expressed concern about declining prioritization of family planning and decreasing donor funding before the KDHS funding before the KDHS results were available (Ministry of Health 2000; NCAPD 2003). The publication of this data provided an opportunity and a resource for champions of family planning to use in their advocacy.

(2) Policy circumstances

Since the time of Kenya's first population policy in the 1960s, family planning has consistently been regarded by policy elites as an issue of ‘business as usual’ rather than a crisis issue. Government officials repeatedly stated that a difficulty for securing prioritization of family planning in the Ministry of Health is that it is not considered to be an emergency, unlike other health issues such as epidemics (I6; I3; I4). During the 1990s, the policy space for family planning narrowed further, when HIV and AIDS was perceived as a crisis issue (Aloo-Obunga 2003; NCPD 2003).

FP has become routine. It has been overrun by other activities like HIV/AIDS. (I4)

This was exacerbated by a perception that family planning and HIV and AIDS are competing issues that can be traded off against each other. This narrowed the policy space for family planning by diverting resources away and undermining acknowledgement of the interdependence between the two services and the need for integrated policies and programmes. One government official commented that:

There was the occasional minister who would prioritize HIV over FP. (I2)

During the 1990s, the deprioritization of family planning seems to have been reinforced by complacency among government officials and politicians about increasing contraceptive use rates and declining fertility. There seems to have been a perception that the fertility transition would continue without the need for continuous government intervention, further undermining the sense of importance of family planning as a policy issue.

People did not realise what was happening when the decline in FP funding started. For a long time, FP had been doing very well. It was at the peak of its success when HIV/AIDS became a crisis issue. [The decline in government prioritization of FP] was an involuntary decrease. (I5)

As demonstrated in Table 1, changing perceptions of policy makers during the first half of the 2000s helped to create a more supportive decision-making environment for family planning. This involved both an increase in concern among policy makers about the issue, and an opening up of policy space because of changing attitudes to HIV and AIDS as a policy issue. By 2003, HIV and AIDS was no longer seen as such an urgent crisis, opening the policy space for policy makers to focus more on family planning.

(3) Policy characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the policy content had an important impact on the nature of the policy space for family planning, but did not present a major change during the period examined by this case study. The decreasing religious opposition to family planning during the 1990s may have helped to increase the acceptability of family planning policy among the electorate, thus expanding policy space slightly. There appears to be insufficient knowledge about how far family planning is accepted by individual Kenyans, but generally it is unlikely to meet strong opposition, although there are high levels of myth and suspicion about particular methods in some communities (Feldblum et al. 2001; I12; I15; 16). However, a defining feature of family planning policy is the lack of a mobilized constituency of supporters for the policy among users of contraceptive services, or the Kenyan public in general (I2; I6; I15; I16). The issue of family planning has therefore tended to involve low political stakes for the Kenyan Government, focusing the costs and benefits of the policy in the bureaucratic domain.

In the bureaucracy, there seem to be no significant incentives to oppose family planning programmes among government officials, with the issue being treated as relatively uncontroversial (I2; I6). As with other health services, contraceptives have relatively intense administrative requirements because of the need for continuous administrative resources to be allocated to procurement, storage and distribution of contraceptive commodities, and the technical skills required for effective service delivery. The capacity of the government to distribute contraceptives beyond the district level to the facility level is weak (I17). As with other areas of the health sector, entrenched vested interests associated with procurement of family planning commodities play an influential role in undermining the implementation of family planning services (I14). These interests continue to frustrate efforts to address inefficiencies in procurement and distribution by improving the effectiveness of KEMSA.

Procurement is worth billions [of Kenyan shillings]. KEMSA became independent recently. But the Ministry of Health [still] wants it. How to let go of a cash cow? The previous minister selected a board chairman, but there is still no board. So there are many vested interests. It has become a donor issue. [Donors] keep saying, ‘let KEMSA go!’. (I17)

The role of advocacy strategies: expanding policy space during the mid-2000s

The previous section has outlined how shifts in context, policy circumstances and policy characteristics leading up to the mid-2000s widened the policy space for family planning. This section focuses on the ways in which policy actors took advantage of these shifts and widened policy space still further through advocacy initiatives. It also examines strategies that were used effectively by these advocates in order to influence key decision-makers.

From 2003 onwards, advocacy activities led by bureaucrats, with support from political, international and civil society actors, led to increased recognition of the importance of contraceptive services among key policy-makers and ultimately resulted in the introduction of the new budget line for contraceptive commodities in 2005. Certain advocacy strategies appear to have been effective in encouraging increased prioritization of the issue, including combining public and intra-government advocacy, organizing focusing events, and using a variety of policy narratives to ‘reframe’ family planning.

The advocacy process involved a range of actors, loosely coordinated through family planning and reproductive health committees chaired by the Ministry of Health, with membership including NCAPD, NGOs and donors. The aims were multifaceted. They included ‘repositioning’ family planning by raising its profile as a government development priority, by making it genuinely multi-sectoral, and enhancing integration with HIV and AIDS and other reproductive health issues such as maternal and child health (I1).

When preliminary results from the KDHS were circulated by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS, since renamed the Kenyan National Bureau of Statistics) in January 2004,5 the deteriorating trends were immediately noted, and the NCAPD carried out further analysis of the KDHS findings, with support from USAID, and held stakeholders’ meetings to discuss how to react (I12). A reproductive health working group, of government officials, NGOs and donors, chaired by the Ministry of Health, identified a specific goal to address donor dependency by ensuring the government allocated national resources to family planning for the first time.

Agenda setting to incorporate family planning in the 2005 budget process involved two advocacy processes. The first was a public process to influence parliamentarians, senior bureaucrats and the wider public, led by NCAPD. The second involved internal government advocacy to influence the budget process within the Ministry of Health and between the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Planning and the Ministry of Finance.

The public efforts centred on the budget process. In April and July 2005, two advocacy workshops were convened by NCAPD, with support from national and international NGOs and donors (NCAPD 2005, 2006b). Presentations and speeches on the importance of family planning and the deteriorating trends were delivered by NCAPD, the African Inter-Parliamentary Network on Reproductive Health and the Ministry of Health. Advocacy materials and presentations (APHRC 2005; NCAPD 2005) drew both from KDHS data and from evidence on the correlation between higher contraceptive prevalence rates, lower fertility rates, and increased maternal and infant survival published by UNFPA (2003). These workshops targeted ministers, senior administrators and budget officials from the Ministries of Finance, Planning and Health, and parliamentarians (I3; I4; I7). The workshops were reported in the press, and key informants argue that this public profile of the event helped to persuade key officials in the bureaucracy to accept and support the allocation of national resources to family planning (I1; I2; I6; I7; I14).

The exact role played by the parliamentarians is hard to pinpoint. Key informants involved in the advocacy argued that the ultimate aim of targeting MPs was to make them become active in the budget process, advocating for resources to be allocated to contraceptives (I6, I14). However, the parliamentarians’ direct impact on the budget is extremely small in Kenya, limited only to simply passing or rejecting the whole budget (Mwenda and Gachocho 2003; Gomez et al. 2004; IPAR 2004). Overall, targeting the parliamentarians may have a more long-term effect through strengthening networks of support for reproductive health among politicians and paving the way for future work with parliamentarians (NCAPD 2006b), rather than directly affecting the budget line. However, it is possible that the parliamentary workshops may have catalysed the budget line decision from the Ministry of Health, by putting senior officials in the ministry under scrutiny about their response to the deteriorating KDHS indicators. In this way, the workshops can be regarded as ‘focusing events’, which raised the profile of the issue, strengthened networks of sympathetic individuals, and mobilized action.

In the parallel, hidden advocacy process, officials within the Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) worked to influence budget officials in the Ministries of Health and Finance to support public funding of contraceptive commodities (I1). NCAPD provided data and other support to the DRH in this process. A line of advocacy was necessary through government hierarchies, where the Head of the DRH took advantage of routine meetings to persuade Ministry of Health budget officials and senior administrators such as the Director of Medical Services of the importance of adding family planning to the budget (I8; I17). In turn, these senior officials had to convey this message to the Ministry of Finance and during multi-sectoral planning meetings such as MTEF meetings.

[The Division of Reproductive Health (DRH)] needs to be able to push the DMS [Director of Medical Services] who oversees the budget under the PS [Permanent Secretary] to make these decisions. There is a line of command from DRH to DMS to PS to the Ministry of Finance. If Kibaru [Head of the DRH] is not shouting enough to the DMS, the DMS will not be shouting to the PS, and so on. (I8)

The decision-making process to allocate government resources to contraceptive commodities began when bureaucrats in NCPAD, DRH and the Ministry of Health Planning Unit variously identified the need for the budget line (I4; I1; I2; I7). The process encompassed ministerial budget meetings and the Medium Term Expenditure process and culminated in the acceptance of the budget by the Minister of Finance. The Planning Unit in the Ministry of Health started the process officially, tabling arguments to the Ministerial Budget Committee charged with formulating the budget. Officials in the Planning Unit presented key budget decision-makers in the Ministry of Health, including the Director of Medical Services and the Permanent Secretary, with arguments about the need for the new budget line based on shortfalls in family planning funding from donors and the implications of declining KDHS indicators for health and development. In turn, the Ministry of Health Budget Committee inserted the budget line into the ministerial budget and defended it to the cross-sector MTEF Secretariat in the Ministry of Finance (I12; I13).

This intra-government advocacy can be seen as a strategy to create a sense of urgency about family planning as a policy problem, in order to create more favourable decision-making dynamics. The KDHS data played an important role, and government economists were said to be receptive to arguments about the importance of access to contraceptives for improving maternal health and child health indicators (I2; I4; I12; I13; I17). The Public Expenditure Review, carried out by the Planning Unit, provided evidence of the fluctuating resources for family planning, which was presented to the Minister and other senior policy-makers in the Ministry of Health to demonstrate that donor funds were unreliable and inadequate without national allocations (I13).

In addition to the use of statistics, a wide range of policy narratives were employed by different actors in their bid to reframe family planning as an important issue for economic growth, development and health, which should be prioritized in public policy-making. Arguments were made to counter a general perception among policy-makers that sustained fertility transitions occur automatically due to socio-economic change, without requiring government intervention (I2; I6). One key informant stated that ‘without continual family planning IEC, acceptance will decline’ (I6). Another key informant argued that argued that,

There is a tendency for poor communities to continually reduce their acceptance of FP […]. FP is not readily accepted by the poor except if they receive information and community-based distribution. Hence the need for continuous IEC provision. (I2)

Particular individuals used various policy narratives, targeting arguments to particular audiences. Key informants explained how the Head of the Division of Reproductive Health used ‘government language’ and internal advocacy within the Ministry of Health to make sure the issue did not seem radical or part of an external agenda (I7, I6). Advocates appealed to nationalism (I2; I3):

NCAPD's argument to the government is: “don't allow the life of your citizens to hang on the whims of donors”. We must have a Plan B – of government money for family planning. (I2)

The slogan ‘Planning our families is Planning for our Nation's Development’ was used in advocacy materials distributed at the advocacy workshops (NCAPD 2005). In advocacy initiatives to influence government officials and parliamentarians, proponents of family planning focused on the importance of family planning for economic and social development and poverty reduction, and specifically for achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (APHRC 2005; NCAPD 2005, 2006a,b).

There were also attempts to transform attitudes among policy elites about the beneficiaries of contraception, highlighting the benefits for men, children, low-income families, and the nation at large, countering popular assumptions that contraception is a ‘women's issue’ (APHRC 2005). Some key informants for this study described the importance of presenting family planning as uncontroversial and in line with national Kenyan aspirations and prevailing gender norms.

With a couple of notable exceptions, reproductive health rights were very rarely used in advocacy materials (APHRC 2005; NCAPD 2005), and remain controversial even among some senior government officials (I17). However, population and sexual and reproductive health narratives were adeptly combined by some key informants, without explicitly referring to rights. One example was the argument that high quality contraceptive services based on a choice of methods are essential for acceptance of contraception by the Kenyan public and for lowering total fertility rates. Shortages of family planning commodities in clinics and poor quality of service delivery were blamed for causing discontinuation of contraceptive use and decreasing acceptance of contraceptive methods (I1, I2, I8).

In the 1990s, there was unmet need for FP. Many women had unintended children. When they went to a facility, they did not find the contraceptive of their choice. They went away, meaning to come back another time, but did not […] When there are shortfalls in FP commodities, fertility goes up automatically. (I1)

Discussion and conclusion

This paper examines the challenge of sustaining commitment to existing policies in politics-as-usual circumstances, rather than focusing on the agenda-setting phase of policy reform, as is more common in the field of policy analysis. Policy space for the issue of family planning in Kenya contracted during the late 1990s, and subsequently began to expand, due both to changing contextual factors and the ways in which advocates within and outside government worked with these factors.

The case study approach brings certain limitations to this paper. In particular, it limits the potential for developing concrete assertions about causality in the policy process or for generalizing about results. However, the paper does support lessons on policy processes from other contexts, and also provides suggestions for how policy space analysis could be utilized more widely in health policy analysis.

Firstly, the paper demonstrates the potential for the use of policy space analysis to identify the challenges and opportunities for sustaining or increasing commitment to existing policies in politics-as-usual circumstances. This is particularly useful for cases involving ‘unplanned drift’ of policies in response to trends such as political pressures or opportunities or shifts in funds provided by global initiatives (Buse et al. 2005).

Policy space analysis can be used both as an analytical framework and as a tool that proponents of a policy issue can use to map the boundaries of policy space and identify the actions that could be undertaken to expand it. Key advantages of the policy space analysis framework include its explicit focus on the dynamics of decision-making circumstances, the influence of vested interests in shaping policy outcomes, and the agency of policy elites (Walt and Gilson 1994). In this way, policy space is a powerful and under-utilized tool for analysis of the political economy of public health policies.

The case study reveals the important role government officials can play in sensitizing colleagues within and between ministries to neglected SRH issues. In Kenya this was dependent on the existence of highly motivated individuals in both the Ministry of Planning and the Ministry of Health, and the existence of the NCAPD, which had the independence and mandate to carry out advocacy on population-related issues.

This case study provides support for Thomas and Grindle's observation that the ‘policy content’ of population policies, involving sustained bureaucratic demands, dispersed benefits and low political stakes, is a likely reason why policies relating to contraceptive services tend to evolve slowly and are often poorly implemented (Thomas and Grindle 1994). In Kenya, the advocacy around family planning and the 2005 budget involved attempts to counter this tendency by securing political commitment and government resources for the issue and addressing complacency by feeding new evidence from the 2003 KDHS into policy. The public advocacy events involving parliamentarians and the media organized by NCPAD and other partners could be seen as an attempt to move the issue from the purely bureaucratic arena into the public domain. The case study demonstrates that research examining policy processes would benefit from investigating budget processes in more detail, because of their role in intra-government negotiation and advocacy for planning and prioritizing policy issues.

In accordance with Walt and Buse (2000), Buse et al. (2005) and Cerny (2002), UNFPA, USAID, other bilateral donors and international NGOs played a vital role in shaping the domestic policy process, first helping to contract, then to expand the policy space for family planning through international support to local advocacy activities. However, while the original expansion of policy space during the 1980s was to a large degree led by international actors, national government officials and resources have played a greater role during the expansion since 2003, providing some evidence of increased national ownership of the issue.

The case study supports Shiffman's assertion of the importance of both the availability of reliable indicators to demonstrate the policy problem and the organization of focusing events (Shiffman 2007). As predicted by Thomas and Grindle (1994), technical analyses of population problems played a central role in persuading policy elites of the need for reform.

The government officials and politicians who support family planning appear to have been skilled at selecting from the range of policy narratives and tailoring their arguments for different audiences. Advocates’ use of arguments to reframe contraceptive services as non-radical and in tune with national development goals and prevailing gender norms can be seen as a useful strategy for increasing recognition of the importance of these services and tackling sources of scepticism about them (Schön and Rein 1991; Joachim 2003). Grindle and Thomas (1991) focus on the implications of policy characteristics for the distribution of costs and benefits to key stakeholders. However, where policy issues that are highly influenced by social and cultural values are concerned, including sexual and reproductive health policies, the ways in which policies are framed to stakeholders may be equally important.

Despite the significant expansion of policy space identified in this case study, very few of the key informants interviewed were of the opinion that contraceptive service delivery and information campaigns have returned to the levels of success experienced during the 1980s. Proponents of family planning in Kenya continue with their efforts to promote family planning as a priority in Kenya and to secure further resources for implementation. However, they may not be able to achieve major improvements in service delivery without successfully tackling the weaknesses in government procurement and distribution of contraceptive commodities.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses her appreciation for the financial support (Grant HD4) to this study provided by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) for the Realising Rights Research Programme Consortium. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DfID.

I am grateful to the key informants from the Ministry of Health, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development, Futures Group, KAPAH, UNFPA, USAID, Marie Stopes International, International Planned Parenthood Federation, and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for taking the time to be interviewed and providing invaluable insights and information for this study. I would like to thank Frederick Mugisha for his contributions to the study design and methodology, and Gill Walt, Lucy Gilson, Sally Theobald, and Eliya Zulu and other staff at APHRC for their helpful advice and comments on previous drafts of the paper.

Endnotes

1 The key informants were from the Ministry of Health [one official in the ministry's Planning Unit and two officials in the Division of Reproductive Health (I3; I4; I13)], the National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development (NCAPD) (I1; I2; I7), the Kenyan National Bureau of Statistics (I12), the donors USAID and UNFPA (I14; I17), and the NGOs Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Futures Group, Kenyan Association for the Promotion of Adolescent Health (KAPAH), and Marie Stopes International (I5; I6; I8; I15; I16). Additional unstructured discussions were carried out with an international adviser to the Ministry of Health (I10), an NGO representative (I11), and a demographer with expertise on family planning in Kenya (I9).

2 The public sector Medical Supplies Coordinating Unit (MSCU) was transformed into a parastatal and renamed KEMSA in 2000.

3 The KDHS 2003 results were published in 2004 but were discussed in meetings during late 2003 within the Ministry of Planning and with other stakeholders.

4 This figure is based on the conversion rate between Kenyan Shillings and US Dollars in June 2005.

5 Although the specific agenda to use advocacy to ‘reposition family planning’ began to appear in government documents during 2005, the agenda appears to have its roots among actors in the then NCPD and supporting US agencies from before the KDHS figures emerged. A 2003 document that does not feature KDHS results cites the need for ‘renewed high-profile public commitment by high-level leaders to reinvigorate FP in Kenya’ (NCPD 2003).

References

- Ajayi A, Kekovole J. Kenya's population policy: from apathy to effectiveness. In: Jain A, editor. Do population policies matter? Fertility and politics in Egypt, India, Kenya and Mexico. New York: Population Council; 1998. pp. 113–56. [Google Scholar]

- Aloo-Obunga C. Country analysis of family planning and HIV/AIDS: Kenya. Washington, DC: the Policy Project; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), City Council of Nairobi, Ministry of Health, and National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development. Repositioning population and reproductive health for the attainment of National and Millennium Development Goals. Report of the Meeting of Parliamentarians, Development Partners and Key Stakeholders in Population and Reproductive Health in Kenya; 19 April 2005; Nairobi. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Blacker J, Opiyo C, Jasseh M, Sloggett A, Ssekamatte-Ssebuliba J. Fertility in Kenya and Uganda: a comparative study of trends and determinants. Population Studies. 2005;59:355–73. doi: 10.1080/00324720500281672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J. The causes of stalling fertility transitions. New York: Population Council; 2005. Working Paper No. 204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making health policy. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy. Theory and Society. 1998;27:3. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics, Kenya, Ministry of Health, Kenya and ORC Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Nairobi: CBS, and Calverton, MD: ORC Macro; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cerny P. Globalizing the policy process: from ‘iron triangles’ to ‘golden pentangles’?. Paper presented at the annual convention of the International Studies Association; 24–27 March 2002; New Orleans. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chimbwete C, Zulu EM. The evolution of population policies in Kenya and Malawi. African Population and Health Research Center, Working Paper No. 27; Nairobi: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, et al. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. The Lancet. 2006;368:1810–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druce N, Dickinson C, Attawell K, Campbell White A, Standing H. Strengthening linkages for sexual and reproductive health, HIV and AIDS: progress, barriers and opportunities for scaling up. London: DFID Health Resource Centre; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Feldblum P, Kuyoh MA, Bwayo JJ, et al. Female condom introduction and sexually transmitted infection prevalence: results of a community intervention trial in Kenya. AIDS. 2001;15:1037–44. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105250-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Global Gag Rule Project. Access denied: the impact of the Global Gag Rule in Kenya. 2006. 2006 Updates. The Global Gag Rule Project.

- Gomez P, Friedman J, Shaprio I. Opening budgets to public understanding and debate: results from 36 countries. Washington, DC: International Budget Project; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Kenya. The Health Sector MTEF 2006/7–2008/9. 2006 Sector Working Group Report (Final Draft), February 2006. Nairobi: Government of Kenya. Online at: http://www.treasury.go.ke/docs/sreports0506/HealthSectorReport.pdf.

- Grindle MS, Thomas JW. Public choices and policy change: the political economy of reform in developing countries. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Policy Analysis and Research (IPAR) Nairobi: IPAR; 2004. Budgetary process in Kenya: enhancement of its public accountability. IPAR Policy Brief 10(1) [Google Scholar]

- Jain A. Do population policies matter? Fertility and politics in Egypt, India, Kenya and Mexico. New York: Population Council; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joachim J. Framing issues and seizing opportunities: the UN, NGOs, and Women's Rights. International Studies Quarterly. 2003;47:247–74. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE. Influencing policy processes for sustainable livelihoods: strategies for change. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; 2001. Lessons for Change in Policy and Organisations, No. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives and public policies. New York: Harper Collins; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew S, Walt G, Lush L, Cleland J. Donor agencies’ involvement in reproductive health: saying one thing and doing another? International Journal of Health Services. 2005;35:579–601. doi: 10.2190/K46B-RRXJ-95M4-JDQU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Family planning and reproductive health commodities in Kenya: background information for policymakers. Nairobi: Division of Primary Health, Ministry of Health, Government of Kenya; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Contraceptive Commodities Procurement Plan 2003–2006. Nairobi: Reproductive Health Advisory Board, Ministry of Health, Government of Kenya; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. National Reproductive Health Policy: Enhancing reproductive health status for all Kenyans. Nairobi: Ministry of Health, Republic of Kenya; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mwenda A, Gachocho M. Budget transparency: Kenyan perspective. Institute of Economic Affairs, Research Paper Series No. 4; Nairobi: 2003. Online at: http://www.internationalbudget.org/resources/library/Kenyatransp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) Nairobi: NCPD, Division of Primary Health Care, Ministry of Health, Government of Kenya and the POLICY Project; 2000. Family Planning Financial Analysis and Projections for 1995 to 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) Family Planning Achievements and Challenges. 2003. Nairobi: NCPD, Ministry of National Planning and Development, Division of Reproductive Health, Ministry of Health, Government of Kenya, Family Planning Association of Kenya and The POLICY Project.

- NCAPD. ‘Calling the Nation to Action’. Fact sheet distributed at the parliamentary meeting on ‘Repositioning Population and Reproductive Health for the Attainment of National and Millennium Development Goals’; 19 April 2005; Nairobi. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- NCAPD. Proposed Workshop of Parliamentary Network on Population and Development to be held on 5–6 May 2006: A summary of initiatives to work with MPs to lobby for support to population and development issues; Nairobi: NCAPD. 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- NCAPD. Launch and Agenda Setting Workshop, Summary of Proceedings; Nairobi: NCAPD. 2006b. [Google Scholar]

- NCAPD, Ministry of Health (MoH), Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), ORC Macro. Kenya Service Provision Assessment Survey 2004. Nairobi: NCAPD, MoH, CBS and ORC Macro; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schön DA, Rein M. New York: Basic Books; 1994. Frame reflection: toward the resolution of intractable policy controversies. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman J. Generating political priority for maternal mortality reduction in 5 developing countries. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:796–803. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JW, Grindle MS. Political leadership and policy characteristics in population policy reform. Population and Development Review. 1994;20(Supplement: The new politics of population: conflict and consensus in family planning):51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ulin P, Robinson E, Tolley E. Qualitative methods in public health: a field guide in applied research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Buse K. Partnership and fragmentation in international health: threat or opportunity? Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2000;5:467–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 1994;9:353–70. doi: 10.1093/heapol/9.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westoff CF, Cross A. The stall in the fertility transition in Kenya. Calverton: ORC Macro; 2006. DHS Analytical Studies No. 9. [Google Scholar]