Abstract

Objective

Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) remains difficult and is often missed in the elderly due to nonspecific and atypical presentation. Diagnostic algorithms able to rule out PE and validated in young adult patients may have reduced applicability in elderly patients, which increases the number of diagnostic tools use and costs. The aim of the present study was to analyze the reported clinical presentation of PE in patients aged 65 and more.

Materials and Methods

Prospective and retrospective English language studies dealing with the clinical, instrumental and laboratory aspects of PE in patients more than 65 and published after January 1987 and indexed in MEDLINE using keywords as pulmonary embolism, elderly, old, venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the title, abstract or text, were reviewed.

Results

Dyspnea (range 59%–91.5%), tachypnea (46%–74%), tachycardia (29%–76%), and chest pain (26%–57%) represented the most common clinical symptoms and signs. Bed rest was the most frequent risk factor for VTE (15%–67%); deep vein thrombosis was detected in 15%–50% of cases. Sinus tachycardia, right bundle branch block, and ST-T abnormalities were the most frequent ECG findings. Abnormalities of chest X-ray varied (less than 50% in one-half of the studies and more than 70% in the other one-half). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe hypoxemia and mild hypocapnia as the main findings. D-Dimer was higher than cut-off in 100% of patients in 75% of studies. Clinical usefulness of D-Dimer measurement decreases with age, although the strategies based on D-Dimer seem to be cost-effective at least until 80 years.

Conclusion

Despite limitations due to pooling data of heterogeneous studies, our review could contribute to the knowledge of the presentation of PE in the elderly with its diagnostic difficulties. A diagnostic strategy based on reviewed data is proposed.

Keywords: pulmonary embolism, diagnosis, elderly, symptoms

Introduction

Despite modern guidelines, ruling out or diagnosing pulmonary embolism (PE) represents one of the main medical problem in clinical geriatric practice (Rogers 2007). PE remains in fact an under-diagnosed disease in old people, even though its incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality increase steadily with age (Kniffin et al 1994; Hansson et al 1997; Silverstein et al 1998; Goldhaber et al 1999; Heit et al 1999; White 2003; Stein et al 2004). It has been reported that PE represented the main cause of death that is less suspected by physicians in the elderly (Leibovitz et al 2001). About 40% of PE found at necropsy in older persons were not suspected ante mortem (Leibovitz et al 2001).

The diagnostic process of PE starts from clinical suspicion both in young adults and in elderly patients (Tapson et al 1999; ESC 2000; ACEP 2003; BTS 2003; Goldhaber and Elliott 2003; Stein et al 2006). Assessment of clinical probability represents the first step to reach a prompt diagnosis of PE and to prevent delays in the diagnostic work-up and initiation of appropriate treatment. Assessment of clinical probability derives from an integration of history, analysis of risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE), symptoms and signs with first level investigations such as systolic blood pressure, 12-leads electrocardiography (ECG), chest X-ray, and arterial blood gas analysis (ABG). Clinical pre-test probability (PTP) should be evaluated by using one of the available and validated score, such as the Wells’ score or the Geneva score (Wells et al 1998; Tapson et al 1999; ESC 2000; ACEP 2003; BTS 2003; Goldhaber and Elliott 2003; Le Gal et al 2006; Stein et al 2006). After assessment of clinical probability, D-Dimer measurement is often the next proposed step in diagnostic strategies for suspected PE (Stein et al 2004). However, D-Dimer assay should be performed only in nonhigh PTP (low or moderate PTP) (BTS 2003). PE may be ruled out when nonhigh PTP is associated to negative D-Dimer (<500 μg/L) (Tapson et al 1999; ESC 2000; ACEP 2003; BTS 2003; Goldhaber and Elliott 2003; Perrier et al 2005; Christopher Study Investigators 2006; Stein et al 2006). In the other cases, PE should be confirmed with helical pulmonary angio-computer tomography (angio-CT), preferably multidetector type, lung scan or pulmonary angiography (Tapson et al 1999; ESC 2000; ACEP 2003; BTS 2003; Goldhaber and Elliott 2003; Stein et al 2006). The use of lung scan for confirming PE has been reduced because of the major availability of helical angio-CT, and in reason of the important proportion of inconclusive lung scan, in particular in elderly patients. Legs ultrasonography is noninvasive, and is able to detect deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The presence of a recent DVT is enough to rule in the diagnosis of PE and DVT and start anticoagulation (Le Gal et al 2006). Combination of PTP with different levels of D-Dimer could reduce the number of unnecessary legs ultrasonography for ruling out DVT in patients with symptomatic PE (Yamaki et al 2007). Trans thoracic echocardiogram (TTE), is particularly useful in suspected massive PE, when unstability of patient precludes complicated diagnostic algorithms. Moreover it could offer information for prognosis stratification and aid the choice of treatment, as biomarkers (B natriuretic peptides and cardiac troponins) (Tapson et al 1999; ESC 2000; Goldhaber 2002; ACEP 2003; BTS 2003; Goldhaber and Elliott 2003; Kucher et al 2003; Pieralli et al 2006; Stein et al 2006; Becattini et al 2007).

Since the evidence showed difficulties in diagnosing of PE in the elderly, the clinical, instrumental and laboratory presentation of PE in elderly patients are reviewed in the present article.

Sources were obtained from articles indexed in MEDLINE database from January 1987 to August 2007 searching terms “pulmonary embolism”, “elderly”, “old”, “venous thromboembolism” in the title, abstract and/or text. Additional references were identified by reviewing the bibliographies of retrieved articles. Only prospective and retrospective English language studies dealing with the clinical, instrumental and/or laboratory presentation of PE patients aged more than 65 years were considered for the review. Studies were included if they reported patients with confirmed PE. We did not perform a systematic review, but we reported data of more relevant articles.

Results

Symptoms, risk factors of VTE, first line instrumental examinations, and arterial blood gas analysis (ABG)

These data derived from twelve selected articles (Busby et al 1988; Stein et al 1991; Jones et al 1993; Gisselbrcht et al 1996; Masotti et al 2000; Ramos et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003; Timmons et al 2003; Kokturk et al 2005; Le Gal et al 2005; Punukollu et al 2005; Chung et al 2006). From ten of them, we derived data for acute mortality, symptoms, signs and risk factors for VTE (Busby et al 1988; Stein et al 1991; Gisselbrcht et al 1996; Masotti et al 2000; Ramos et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003; Timmons et al 2003; Kokturk et al 2005; Le Gal et al 2005; Punukollu et al 2005); from seven articles we derived data for 12-leads ECG (Stein et al 1991; Masotti et al 2000; Ramos et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003; Timmons et al 2003; Kokturk et al 2005), from six data for chest X-ray (Busby et al 1988; Stein et al 1991; Masotti et al 2000; Ramos et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003; Le Gal et al 2005), from four data for TTE and from seven data for ABG (Stein et al 1991; Jones et al 1993; Gisselbrcht et al 1996; Masotti et al 2000; Ramos et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003; Kokturk et al 2005).

Dyspnea (range 59%–91.5%), tachypnea (46%–74%), tachycardia (29%–76%), and chest pain (range 26%–59%) represented the main symptoms reported in clinical studies about PE in the elderly. Bed rest (range 15%–67%) and DVT (range 15%–50%) were the main risk factors for VTE (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main clinical aspects of elderly patients with PE

| Reference Year | Busby 1988 | Stein 1991 | Gisselbrecht 1996 | Ramos 2000 | Masotti 2003 | Ceccarelli 2003 | Timmons 2003 | Punukollu 2005 | Koktur 2005 | Le Gal 2005 | Tot./Range (1988–2005) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | R | P | P | R | R | R | R | P | R | P | |

| Diagnostic | V/Q scan | V/Q scan/ | Q scan/ | V/Q scan/ | Q scan | Q scan | hCT | V/Q scan/ | V/Q scan | hCT | |

| Method | pulmonary angiography | pulmonary angiography | pulmonary angiography | hCT | |||||||

| Patient Number | 37 | 72 | 26 | 64 | 68 | 59 | 29 | 70 | 58 | 167 | 650 |

| Male/female | 17/20 | 32/40 | 10/16 | 24/40 | 22/46 | 18/41 | 12/17 | 29/41 | 21/37 | 61/106 | 246/404 |

| Mean Age(years ± SD) | 76 | ≥70 | 80 ± 3 | 69 ± 17 | 78.6 ± 7.7 | 81.9 ± 5.2 | 74.7 | 76.4 ± 8.37 | 72.7 ± 6.1 | ≥75 | (65–99) |

| Mortality | 21.6% | nr | 11.5% | 8% | 29.5% | 32% | nr | 17% | nr | nr | (8%–32%) |

| Symptoms and signs | |||||||||||

| Dyspnea | 65% | 78% | 85% | 66% | 88% | 91.5% | 59% | 74% | 84.5% | 81.9% | (59–91.5%) |

| Tachycardia | nr | 29% | nr§ | nr* | 74% | 67% | 31% | 44% | nr | 32.9% | (29–76%) |

| Chest pain | 57% | 51% | 35% | 27% | 40% | 39% | 59% | 26% | 48.3% | 46.1% | (26–57%) |

| Tachypnea | 46% | 74% | nr | nr | 50% | 47% | nr | nr | nr | 73.1% | (46–74%) |

| Syncope | 8% | nr | 62% | 11% | 13.5% | 20% | nr | 19% | 27.6% | 18.6% | (8–62%) |

| Shock | 5% | 10% | 31% | nr | 13.5% | 18% | 24% | nr | nr | nr | (5–31%) |

| Cough | 43% | 35% | nr | 12% | 22% | 20% | 24% | nr | 16% | nr | (12–43%) |

| Hemoptysis | 11% | 8% | 0% | 3% | nr | nr | 14% | nr | 6.9% | 4.8% | (3–14%) |

| Risk factors | |||||||||||

| Bed rest | 25% | 67% | 15% | 45% | 65% | 54% | nr | 21% | 40% | nr | (15%–67%) |

| DVT | 16% | 15% | 50% | 47% | 35% | 34% | 16% | 19% | 44.8% | nr | (15%–50%) |

| Cancer | 32% | 26% | 4% | 20% | 16.5% | 18.5% | nr | 30% | 13.8% | 9.0% | (4%–32%) |

| Surgery | 22% | 44% | 19% | 14% | 7% | 5% | nr | 9% | 26% | 6.6% | (5%–44%) |

| Heart failure | 30% | nr | nr | 33% | 25% | 32% | nr | nr | 5% | 15% | (5%–33%) |

| Previous DVT/PE | 27% | nr | 19% | 18% | 24% | 23.5% | nr | 19% | 35% | 41% | (18%–41%) |

| Stroke | 11% | nr | nr | nr | 13.5% | 12% | nr | nr | nr | 3% | (3%–13.5%) |

| AMI | 11% | nr | nr | nr | nr | 3% | nr | nr | nr | nr | (3%–11%) |

| COPD | nr | nr | nr | nr | 13.5% | 27% | nr | nr | 2% | 8.4% | (2%–27%) |

Abbreviations:DVT, deep vein thrombosis; AMI, Acute myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; nr, not reported;

Mean heart rate 95 ± 17 beats for minute;

mean heart rate 100 ± 16 beats for minute;

°Right ventricular failure 46%; the study of Gisselbrecht15 was referred to massive pulmonary embolism. V, ventilation; Q, perfusion; hCT, helical computer tomography. R, retrospective; P, prospective.

Sinus tachycardia (range 18%–62.5%), right bundle branch block (4.5%–40.5%) and ST-T abnormalities (9%–37%) were the most represented 12-leads-ECG findings; the typical S1Q3/S1Q3T3 ECG pattern was found in 4.5%–14% of patients.

Three studies reported abnormalities in less of one half of patients at chest X-ray (Busby et al 1988; Ramos et al 2000; Le Gal et al 2005) while in other three studies more than 70% of patients had abnormalities (Stein et al 1991; Masotti et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003). Cardiomegaly (range 22%–64%), pleural effusion (15.8%–57%), and (8.5%–71%) were the most frequent reported aspects. More than 50% of patients had features of right heart overload at TTE (Masotti et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003; Kokturk et al 2005; Chung et al 2006).

A severe hypoxemic respiratory failure was found as main ABG pattern. In five studies, this pattern was associated to low arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2). In three studies the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient, D(A-a)O2, was analyzed (Jones et al 1993; Masotti et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003), and was found to be elevated (range 44.8–46.6 mmHg).

Table 2 summarizes the first line instrumental findings.

Table 2.

12-leads electrocardiography, chest X-ray, arterial blood gas analysis findings 12-leads ECG

| Reference Year | Stein 1991 | Ramos 2000 | Masotti 2003 | Ceccarelli 2003 | Timmons 2003 | Kokturk 2005 | Tot./Range (1988–2005) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 21% | nr | nr | nr | nr | 50% | (21%–50%) | |

| Sinus tachycardia | nr | nr | 60% | 62.5% | 18% | nr | (18%–62.5%) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | nr | 20% | 20% | 20.5% | 7% | 13.6% | (7%–20.5%) | |

| RBBB | 9% | 9% | 27% | 40.5% | 18% | 4.5% | (4.5%–40.5%) | |

| S1Q3/S1Q3T3T3 | nr | 8% | 12% | 8.5% | 14% | 4.5% | (4.5%–14%) | |

| ST-T abnormalities | 56% | 22% | 34% | 51% | 4% | 13.6% | (4%–56%) | |

| Chest X-ray | ||||||||

| Reference Year | Busby 1988 | Stein 1991 | Ramos 2000 | Masotti 2003 | Ceccarelli 2003 | Le Gal 2005 | Tot./Range (1988–2005) | |

| Abnormal | 38% | 96% | 43% | 80.5% | 86.5% | nr | (38%–96%) | |

| Cardiomegaly | nr | 22% | 20% | 58% | 64% | nr | (22%–64%) | |

| Pulmonary edema | nr | 13% | nr | 13.5% | 30.5% | nr | (13%–30.5%) | |

| Pleural effusion | 16% | 57% | nr | 18% | 17% | 15.8% | (15.8%–57%) | |

| Atelectasis | 22% | 71% | 14% | 15% | 8.5% | 14% | (8.5%–71%) | |

| Hemidiaphragm elevation | nr | 28% | nr | nr | 8.5% | 18.2% | (8.5%–28%) | |

| ABG | ||||||||

| Reference Year | Stein 1991 | Jones et al 1993 | Gisselbrecht 1996 | Ramos 2000 | Masotti 2003 | Ceccarelli et al 2003 | Kokturk et al 2005 | Tot./Range (1988–2005) |

| Mean paO2(mmHg) | 61 ± 12 | 61.4 | 55 ± 9 | 60 ± 10 | 54.6 ± 14.7 | 53.5 ± 15.4 | 59.5 ± 9.8 | (53.5–61.4) |

| Mean paCO2(mmHg) | nr | nr | 30 ± 5 | 33 ± 5 | 41.7 ± 15 | 42.1 ± 16.5 | 32.9 ± 9.8 | (30–42.1) |

| Mean [D(A-a)O2] (mmHg) | nr | 46.6 | nr | nr | 45.3 ± 22.4 | 44.8 ± 21.6 | nr | (44.8–46.6) |

Abbreviations: paO2, oxygen arterial partial pressure; paCO2, dioxide arterial partial pressure; D(A-a)O2, alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient; nr, not reported nr, not reported; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Pre-test clinical probability and D-Dimer

Two studies have analyzed the field of applicability of PTP combined with D-Dimer for ruling out PE in the elderly (Righini et al 2004; Söhne et al 2005). These studies have reported that the percentage of high PTP increases in elderly compared to younger patients, whereas the percentage of low PTP decreases. One study suggested that Geneva score seemed to perform better in elderly patients compared to Wells score (Righini et al 2004). One of these studies has demonstrated that the sensitivity and negative predictive value of a combination of low PTP and negative D-Dimer were high in elderly patients. Unfortunately the prevalence of elderly having the association non high PTP-negative D-Dimer is low (14% of age over than 75 years) (Sühne et al 2005). However a strategy combining PTP and D-Dimer is still cost-effectiveness at least until 80 years (Righini et al 2007).

The specificity of D-Dimer in patients with suspected PE decreases steady with age. One study has demonstrated that the specificity of ELISA D-Dimer (VIDAS, Biomerieux, France) in suspected VTE reduces from 70.5% in patients under 40 years to 4.5% in patients over 80 years (Harper et al 2007). Similar specificity (5%) was found in another study in patients over 80 years with nonhigh PTP by using the same ELISA D-Dimer method (Righini et al 2000). The very low specificity of D-Dimer in the elderly has led to suggest an increased cut-off value of D-Dimer. Two series have concluded that an increased cut-off of D-Dimer reduced the false positives but increased the percentage of false negatives. Conversely, another study has demonstrated that increasing the cut-off from 500 microg/L to 750 microg/L and 1000 microg/L, led to a rise in D-Dimer specificity in patients over 80 years (from 4.5% to 13.1% and 27.3%, respectively) without loss of sensibility (Aguilar et al 2001; Righini et al 2001; Harper et al 2007).

One study (Masotti et al 2000) has shown that 86% of patients with PE had D-Dimer >500 μg/L measured with latex agglutination. In another study D-Dimer, measured by immunoturbidimetric method, was over the cut-off value in 98.5% of patients (Sühne et al 2005). Four studies demonstrated that all patients (100%) had D-Dimer values higher than cut-off (Tardy et al 1998; Barro et al 1999; Masotti et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003).

Instrumental examinations for confirming PE

Two studies have analyzed the effect of age on the diagnostic performance of helical angio-CT to diagnose PE. Either by single detector or multidetector helical pulmonary angio-CT, the sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values are not influenced by age, making applicable and safe the diagnostic strategies based on these investigations (Righini et al 2004; Stein et al 2007).

In selected elderly patients without previous cardiopulmonary diseases ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) lung scan has similar applicability in the elderly compared with younger patients (Stein et al 1996). In unselected patients, rate of non diagnostic lung scan is higher in elderly patients (Calvo-Romero et al 2005). The diagnostic yield of lung scan decreases from 68% in patients under 40 years to 42% in the patients aged 80 years and older (Righini et al 2000).

Sensitivity of legs ultrasonography for detection of DVT increase with age, whereas specificity does not change with age, close to 100% (Righini et al 2000).

Sensitivity and specificity of pulmonary angiography remain similar to young adults but this procedure could be limited by higher risk of acute renal failure due to iodinate contrast (Stein et al 1991).

A recent meta-analysis on prognostic values of cardiac troponins has shown that elevated levels of troponins identify high risk patients for death and adverse outcomes, even though in the studies concerning patients with mean age ≥65 years. (Giannitsis et al 2000; Enea et al 2004; Hsu et al 2006; Kaczynska et al 2006; Becattini et al 2007). One study has evaluated the prognostic role of BNP in the elderly, and concluded that this biomarker was not a solid indicator of complicated PE (Ray et al 2006).

Discussion and implications for clinical practice

The two crucial questions about PE in the elderly are: in which patients should PE be suspected and searched for, and which diagnostic procedures and algorithms could be safely performed.

PE represents one of the main causes of acute respiratory failure (ARF) in the elderly patients. In a recent observational study on 514 elderly patients with ARF, 18% of them had confirmed PE. An inappropriate initial treatment due to uncorrected diagnosis was associated to an increased mortality (Ray et al 2006). PE was one of the main causes incorrectly diagnosed (Ray et al 2006).

In elderly patients, making the difference between PE symptoms and other cardio-respiratory diseases such as congestive heart failure, pneumonia and/or COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) exacerbation could be very challenging because of the frequent similar clinical picture and coexistence of diseases (Ray et al 2006). As shown in the present study, the most frequent symptoms and signs of confirmed PE in elderly patients are dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, and chest pain. All these symptoms and signs are nonspecific and similar to that of PE in younger patients (PIOPED Investigators 1990; Miniati et al 1996; Goldhaber et al 1999). Chest pain seem to be less frequent and tachycardia and syncope more frequent in the elderly compared with nonelderly patients (Busby et al 1988; Stein et al 1991; Gisselbrcht et al 1996; Kokturk et al 2005; Punukollu et al 2005). Bed rest is the most frequent risk factors for PE in the elderly, together with surgery and cancer. Evident implication is that primary prophylaxis using mechanical or pharmacological measures should be carefully evaluated in elderly bedridden patients. (PIOPED Investigators 1990; Miniati et al 1996; Goldhaber et al 1999).

The specificity of instrumental and laboratory examinations is low both in elderly and nonelderly patients: 12-leads-ECG, chest X-ray, and ABG do not increase the suspicion of PE in the elderly.

ABG could reveal an hypoxemic respiratory failure associated to normal or mildly reduced PaCO2 and increased D(A-a)O2 similarly to congestive heart failure and pneumonia. It should be kept in mind that in two studies enrolling patients with previous cardio-pulmonary diseases, mean values of PaCO2 were in normal range. Only one third of patients had respiratory alkalosis (Masotti et al 2000; Ceccarelli et al 2003), suggesting an impaired response to acute stress in elderly patients. Compared with younger patients, ABG in elderly patients seems to reveal lower hypoxemia and higher values of alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient (PIOPED Investigators 1990).

The role of D-Dimer is well recognized to rule out PE when it is negative and associated to a non-high PTP. However, the specificity and the clinical usefulness of D-Dimer decrease with age because of high percentage of elderly patients with D-Dimer higher than cut-off. Unfortunately increasing cut-off of D-Dimer could lead to increase the percentage of patients wrongly considered negatives, and is therefore considered unsafe.

Recently, the first diagnostic algorithm, not validated, for suspected PE in the elderly has been reported (Righini et al 2005). The most important findings of this diagnostic strategy are represented by the non invasivity of first-line investigation (PTP evaluation, and legs ultrasonography), and angio-CT as confirming examination. In this algorithm D-Dimer is not widely recommended; its assay should be reserved to selected conditions (limited availability of other diagnostic tests or presence of high risk of adverse reactions due to instrumental examinations with contrast). However, more recently the same Authors demonstrated that in elderly outpatients the strategies based on PTP evaluation, and D-Dimer assay are cost-effectiveness at least until 80 years and that strategies with legs ultrasonography are more expensive but not safer. Therefore, measuring D-dimer in outpatients more than 80 years may be differently appreciated. On one side, one could argue that the clinical usefulness is so limited that D-dimer measurement is not indicated. On the other side, D-dimer measurement does not increase the costs of diagnostic strategies. To avoid complicated recommendations or age-adapted diagnostic strategies (for example not dosing D-dimer in elderly patients), a systematic measurement may be proposed, at least in outpatients. Moreover, D-dimer might still be justified in patients above 80 years when the availability of other diagnostic tests is limited or when the risk of imaging using hCT is higher because of impaired renal function.

Helical pulmonary angio-CT should be encouraged in the elderly since it has been proved to be safe and accurate in the oldest and since lung scan has limited accuracy in this subset of patients. (Stein et al 1996; Righini et al 2000, 2004; Calvo-Romero et al 2005; Stein et al 2007).

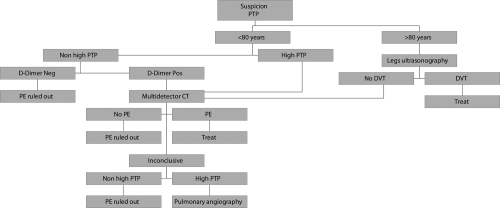

Figure 1 shows an algorithm for elderly patients with suspected PE derived from the most recent evidence of literature.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic algorithm for elderly patients with suspected PE derived from literature evidence.

Limits of the study

We are aware of some limitations of our review. First we pooled data from heterogeneous studies with different methodology. This review was not systematic and could be scientifically subjected to criticism. Studies about diagnostic strategy for diagnosing PE in the elderly are lacking, and our conclusions are based upon small series. Table 3 summarizes the implications of this review in the clinical practice.

Table 3.

Implications for clinical geriatric practice

| Incidence, prevalence, morbidity and mortality increase steadily with age |

| PE is the acute cause of death in the elderly that is least suspected by physicians |

| Comorbidity could influence symptoms and signs |

| Spectrum of differential diagnosis of PE is wider in elderly patients due to high prevalence of cardio-respiratory diseases in these patients |

| Higher percentage of elderly patients have high PTP compared with younger patients |

| Low percentage of elderly patients with suspected PE have nonhigh PTP and negative D-dimer |

| Specificity of D-Dimer reduces with age |

| Increased cut-off of D-Dimer could reduce false positives but, unfortunately, could increase false negatives |

| 12-leads electrocardiogram, chest X-ray and echocardiogram could have a lower specificity with respect to younger patients |

| Hypoxemia and increased alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient have a high sensitivity and low specificity |

| Respiratory and metabolic acidosis could be more frequent compared with younger patients |

| Lung scan could be less useful in the elderly for higher percentage of patients with pre-existing pulmonary diseases or abnormal chest X-ray |

| Single detector and multidetector pulmonary angio-CT seem to be not influenced by age |

| Pulmonary angiography could be limited in the elderly because of the higher risk of side effects compared with younger patients |

Conclusion

PE is a potentially life-threatening condition, difficult to diagnose in elderly patients. Misdiagnosis is more frequent in the elderly patients Clinical signs of PE are neither sensitive nor specific enough to rule in or out the diagnosis. Our review suggests that PE should be suspected in any elderly patient at risk with unexplained dyspnea, tachypnea, or tachycardia. However these findings are highly nonspecific, which reduces the diagnostic value.

References

- [ACEP] American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee; Clinical Policies Committee Subcommittee on Suspected Pulmonary Embolism. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:257–70. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar C, Martinez A, Martinez A, et al. Diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis in the elderly: a higher D-Dimer cut-off value is better? Haematologica. 2001;86:E28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barro C, Bosson JL, Pernod G, et al. D-Dimer testing improves the management of thromboembolic disease in hospitalized patients. Throb Res. 1999;95:263–9. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(99)00042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becattini C, Agnelli G. Acute pulmonary embolism: risk stratification in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2007;2:119–29. doi: 10.1007/s11739-007-0033-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becattini C, Vedovati MC, Agnelli G. Prognostic value of troponins in acute pulmonary embolism. A meta-analysis. Circulation. 2007;116:427–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [BTS] British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of suspected acute pulmonary embolism. Thorax. 2003;58:470–84. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.6.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby W, Bayer A, Pathy J. Pulmonary embolism in he elderly. Age Ageing. 1988;17:205–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/17.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Romero JM, Lima-Rodriguez BM, Bureo-Dacal P, et al. Predictors of an intermediate ventilation/perfusion lung scan in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12:129–31. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200506000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli E, Masotti L, Barabesi L, et al. Pulmonary embolism in very old patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15:117–22. doi: 10.1007/BF03324488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Emmett L, Khoury V, et al. Atrial and ventricular echocardiographic correlates of the extent of pulmonary embolism in the elderly. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:347–53. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enea I, Ceparano G, Mazzarella G, et al. Biohumoral markers and right ventricular dysfunction in acute pulmonary embolism: the answer to thrombolytic therapy. Ital Heart J Suppl. 2004;5:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [ESC] ESC Task Force. Guidelines on diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1301–36. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannitsis E, Muller-Bardoff M, Kurowski V, et al. Independent prognostic value of cardiac troponin T in patients with confirmed pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2000;102:211–17. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselbrcht M, Diehl J, Meyer G, et al. Clinical presentation and results of thrombolytic therapy in older patients with massive pulmonary embolism: a comparison with non-elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:189–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber SZ, Elliott CG. Acute pulmonary embolism: part I. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis. Circulation. 2003;108:2726–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097829.89204.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, De Rose M, for ICOPER Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) Lancet. 1999;353:1386–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber SZ. Echocardiography in the management of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:691–700. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson PO, Welin L, Tibblin G, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in the general population. The study of men born in 1913. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1665–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper PL, Theakstone E, Ahmed J, et al. D-Dimer concentration increases with age reducing the clinical value of the D-Dimer assay in the elderly. Intern Med J. 2007;37:607–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. Predictors of survival after deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 159:445–53. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JT, Chu CM, Chang ST, et al. Prognostic role of right ventricular dilatation and troponin I elevation in acute pulmonary embolism. Int Heart J. 2006;47:775–81. doi: 10.1536/ihj.47.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JS, VanDeelen N, White L, et al. Alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient in elderly patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1177–81. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynska A, Pelsers MM, Bochowicz A, et al. Plasma heart-type fatty acid binding protein is superior to troponin and myoglobin for rapid risk stratification in acute pulmonary embolism. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;371:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniffin WD, Jr, Baron JA, Barrett J, et al. The epidemiology of diagnosed pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:861–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokturk N, Oguzulgen IK, Demir N, et al. Differences in clinical presentation of pulmonary embolism in older vs younger patients. Circ J. 2005;69:981–6. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucher N, Wallmann D, Carone A, et al. Incremental prognostic value of troponin I and echocardiography in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1651–6. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Differential value of risk factors and clinical signs for diagnosing pulmonary embolism according to age. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2457–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165–71. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovitz A, Blumenfeld O, Baumoehl Y, et al. Postmortem examinations in patients of a geriatric hospital. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2001;13:406–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03351510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masotti L, Ceccarelli E, Cappelli R, et al. Plasma D-Dimer levels in elderly patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2000;98:577–9. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(00)00193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masotti L, Ceccarelli E, Cappelli R, et al. Pulmonary embolism in the elderly: clinical, instrumental and laboratori aspects. Gerontology. 2000;46:205–11. doi: 10.1159/000022161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miniati M, Pistolesi M, Marini C, et al. Value of perfusion lung scan in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: results of Prospective Investigative Study of Acute Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis (PISA-PED) Am J Critic Care Med. 1996;154:1387–93. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.5.8912753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Eng J Med. 2005;352:1760–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieralli F, Olivotto I, Vanni S, et al. Usefulness of bed-side testing for brain natriuretic peptide to identify right ventricular dysfunction and outcome in normotensive patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1386–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punukollu H, Khan IA, Punukollu G, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism in elderly: clinical characteristics and outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2005;99:213–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A, Murillas J, Mascias C, et al. Influence of age on clinical presentation of acute pulmonary embolism. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2000;30:189–98. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(00)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P, Birolleauu S, Lefort Y, et al. Acute respiratory failure in the elderly: etiology, emergency diagnosis and prognosis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R82. doi: 10.1186/cc4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P, Maziere F, Medimagh S, et al. Evaluation of B-type natriuretic peptide to predict complicated pulmonary embolism in patients aged 65 years and older: brief report. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:603–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righini M, Bounemeaux H, Perrier A. Effect of age on the performance of single detector helical computer tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:296–9. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righini M, de Moerloose P, Reber G, et al. Should the D-Dimer cut off value be increased in elderly patients suspected of pulmonary embolism? Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righini M, Goehring C, Bounameaux H, et al. Effect of age on the performance of common diagnostic tests for pulmonary embolism. Am J Med. 2000;109:357–61. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righini M, Le Gal G, Perrier A, et al. Effect of age on the assessment of clinical probability of pulmonary embolism by prediction rules. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1206–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righini M, Le Gal G, Terrier A, et al. The challenge of diagnosing pulmonary embolism in elderly patients: influence of age in commonly used diagnostic tests and strategies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1039–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righini M, Nendaz M, Le Gal G, et al. Influence of age on the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies for suspected pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1869–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RL. Venous thromboembolic disease in the elderly patients: atypical, subtle, and enigmatic. Clin Geriatr Med. 23:413–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, et al. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A 25-years population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:585–93. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söhne M, Kamphuisen PW, van Mierlo PJ, et al. Diagnostic strategy using a modified clinical decision rule and D-Dimer test to rule out pulmonary embolism in elderly in- and outpatients. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:206–10. doi: 10.1160/TH04-11-0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PD, Beemath A, Quinn DA, et al. Usefulness of multidetector spiral computed tomography according to age and gender for diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1303–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PD, Gottschalk A, Saltzman HA, et al. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism in the elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:1452–7. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90674-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PD, Henry JW, Relyea B, et al. Elderly patients with no prior cardiopulmonary disease show ventilation/perfusion lung scan characteristics that are sensitive and specific for pulmonary embolism. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 1996;5:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PD, Hull RD, Kayali F, et al. Venous thromboembolism according to age: the impact of an aging population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2260–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PD, Hull RD, Patel KC, et al. D-Dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:589–602. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PD, Woodard PK, Weg JG, et al. Diagnostic pathways in acute pulmonary embolism: recommendations of the PIOPED II investigators. Am J Med. 2006;119:1048–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapson VF, Carroll BA, Davidson BL, et al. The diagnostic approach to acute venous thromboembolism. Clinical practice guideline. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1043–66. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.16030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardy B, Tardy-Pancet B, Viallon A, et al. Evaluation of D-Dimer ELISA test in elderly patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PIOPED Investigators. Value of the ventilation/perfusion scan in acute pulmonary embolism. Results of the Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis (PIOPED) JAMA. 1990;263:2753–59. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440200057023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons S, Kingston M, Hussan M, et al. Pulmonary embolism: differences in presentation between older and younger patients. Age Ageing. 2003;32:601–5. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells PS, Ginsberg JS, Anderson DR, et al. Use of a clinical model for safe management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;129:997–1005. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(Suppl 1):I4–18. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Writing Group for Christopher Study Investigators. Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computer tomography. JAMA. 2006;295:172–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaki T, Nozaki M, Sakurai H, et al. Uses of different D-dimer levels can reduce the need for venous duplex scanning to rule out deep vein thrombosis in patients with symptomatic pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:526–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]