Abstract

Proton NMR spectroscopy at 7 Tesla (7T) was evaluated as a new method to quantify human fat composition noninvasively. In validation experiments, the composition of a known mixture of triolein, tristearin, and trilinolein agreed well with measurements by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Triglycerides in calf subcutaneous tissue and tibial bone marrow were examined in 20 healthy subjects by 1H spectroscopy. Ten well-resolved proton resonances from triglycerides were detected using stimulated echo acquisition mode sequence and small voxel (∼0.1 ml), and T1 and T2 were measured. Triglyceride composition was not different between calf subcutaneous adipose tissue and tibial marrow for a given subject, and its variation among subjects, as a result of diet and genetic differences, fell in a narrow range. After correction for differential relaxation effects, the marrow fat composition was 29.1 ± 3.5% saturated, 46.4 ± 4.8% monounsaturated, and 24.5 ± 3.1% diunsaturated, compared with adipose fat composition, 27.1 ± 4.2% saturated, 49.6 ± 5.7% monounsaturated, and 23.4 ± 3.9% diunsaturated. Proton spectroscopy at 7T offers a simple, fast, noninvasive, and painless method for obtaining detailed information about lipid composition in humans, and the sensitivity and resolution of the method may facilitate longitudinal monitoring of changes in lipid composition in response to diet, exercise, and disease.

Keywords: fatty acids, triglycerides, spectroscopy, metabolism, bone marrow, subcutaneous fat, musculoskeletal, lipid composition, in vivo

Adipose mass and the anatomic distribution of adipose tissue strongly influence the risk of multiple diseases. The fatty acid composition of adipose tissue may also influence predisposition to various disorders including cancer (1, 2), type 2 diabetes (3–6), and heart disease (7). Nevertheless, the relations among adipose tissue composition and the risk of disease are controversial and difficult to study, in part because of the traditional requirement for invasive biopsy. Noninvasive analysis of fat composition in humans by 1H NMR spectroscopy would have major advantages, because the study could be integrated into routine exams. Under high-resolution analytical conditions, signals from protons adjacent to double bonds are easily resolved, and it is a relatively simple matter to assess fat composition by 1H NMR spectroscopy (8–12). However, extension of these methods to human applications is challenging because chemical shift resolution observed in vivo at 1.5 or 3.0 Tesla (T) is substantially worse than in analytical spectrometers. Because of the intense current interest in triglyceride composition and metabolism, several alternatives have been suggested, including selective detection of polyunsaturated fatty acids in animal models at 4.7 T (13), two-dimensional NMR at 3 T (14), and 1H-decoupled 13C NMR spectroscopy (15–19). The large chemical shift dispersion of 13C is a major advantage compared with 1H observations. Wide application, however, is limited by the requirement for additional coils and a second radiofrequency channel.

Chemical shift resolution in the 1H spectrum should, in principle, improve at higher fields. Recently, the fatty acid composition of mouse adipose tissue was reported based on 1H spectra obtained in vivo at 7T, where the chemical shift dispersion allows assignment of signals from protons adjacent to double bonds. One advantage of this analysis (20) was the use of spectroscopic data from three adjacent resonances with a frequency bandwidth (BW) of only 0.74 ppm (221 Hz at 7T). In other reports (8), triglyceride saturation was determined from the olefinic protons (-CH = CH-, at ∼5.31 ppm) by using the CH3 methyl protons (at ∼0.90 ppm) as the reference. These two resonances span a frequency range of 4.41 ppm (1,314 Hz at 7T). The wide BW may result in less-uniform excitation profiles, and the use of frequency-dependent spatial localization yields spectra with resonances originating in different physical locations, an artifact known as chemical shift displacement.

The ability to noninvasively monitor triglyceride composition using proton spectroscopy would have wide applications in clinical research. In this study, the approach described by Strobel, van den Hoff, and Pietzsch (20) to measuring fatty acid composition by 1H NMR spectroscopy in mice was tested in phantoms and extended to healthy human subjects. The fatty acid composition of bone marrow measured by NMR in this study was in good agreement with some (12) but not all (21) reports of fatty acid composition by gas chromatography. The NMR determination of saturated fatty acids in extremity subcutaneous fat agreed well with gas chromatographic analysis of abdominal subcutaneous fat, about 27% of fatty acids. Somewhat lower values for monounsatured fats, about 50%, were found by NMR, compared with 57% found in biopsy studies. The principles used by numerous investigators to quantify fat composition by 1H NMR (8–12, 20) are easily extended to human studies at 7T, where high-quality 1H NMR spectra can be obtained routinely.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human MR spectroscopy

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study. Twenty healthy adults (twelve females and eight males) age 22–52 years (average 34 years; without diabetes or known vascular disease) were studied supine or prone in a 7T system (Achieva, Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, OH). Spectra were acquired with a partial-volume quadrature transmit/receive coil customized to fit the shape of a human calf. Axial, coronal, and sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echo images were initially acquired of the left calf muscle. Typical parameters were: field of view 180 × 180 mm, repetition time (TR) 1,500 ms, echo time (TE) 75 ms, turbo factor 16, and number of acquisitions (NA), 1. Single-voxel stimulated echo acquisition mode (STEAM) (typical parameters: voxel size 5 × 5 × 5 mm3 (∼0.1 ml), TR 2,000 ms, TE 20 ms, spectral BW of 4 kHz, number of points (NP) 4,096 and zero-filled to 8,192 prior to Fourier transform, NA 16, no water suppression) was used to acquire 1H spectra from tibial bone marrow and subcutaneous fat tissue. To correct individual resonances for relaxation effects, T1 and T2 were measured in seven of the subjects. T1 was measured using inversion-recovery, with nine inversion delay times in the range of 5 ms to 3,000 ms, with TR 7 s and TE 40 ms. T2 was measured by using ten TE values from 20 ms to 180 ms, with TR 8 s. Subjects were instructed to move slowly in the scan room. The entire scanning session was 60 min or less and it was well-tolerated by all subjects. All subjects were interviewed after the exam and again at 24 h after the exam. All subjects specifically denied dizziness, nausea, vertigo, headaches, or visual changes.

Phantom studies

Pure triacylglycerols were obtained from Nu-Chek Prep, Inc. (Elysian, MN). To test the accuracy of the protocol to quantify lipid composition, phantom samples were prepared by mixing tristearin (18:0) (number of carbons:number of double bonds), triolein (18:1), and trilinolein (18:2) in the following ratios: 50:0:50, 50:10:40, 50:20:30, 50:30:20, 50:40:10, 50:50:0, and 25:50:25. Phantom samples with composition of different chain lengths of triglyceride were prepared by mixing tripalmitin (16:0) and tristearin (18:0) in the following ratios: 100:0, 80:20, 75:25, 50:50, 25:75, 20:80 and 0:100. All mixtures were dissolved in CD3Cl in 4 ml glass vials, which were then mounted in the center of a 150 ml beaker filled with deionized water. Typical magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) parameters were: TR 8 s, TE 11 ms, voxel size 0.2 ml, NP 16 k, BW 8 kHz, NA 128. The triglyceride composition was calculated as described below.

Spectral analysis

The 1H chemical shift of in vivo fat resonances from bone marrow and subcutaneous tissue was assigned such that the methyl signal was at 0.9 ppm. Resonance areas were determined by fitting the spectra with Voigt shapes (variable proportions of Lorentzian plus Gaussian) on ACD software (Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc., Toronto, Canada) after phasing and baseline correction. Peak areas for each individual resonance were corrected with its corresponding T1 and T2. Lipid composition was evaluated after correction for relaxation effects.

Calculation of triglyceride composition

Human adipose tissue is composed largely of triglycerides. Seven fatty acids predominate as follows (number of carbons:number of double bonds, typical abundance): myristic (14:0, 3%), palmitic (16:0, 19–24%), palmitoleic (16:1, 6–7%), stearic (18:0, 3–6%), oleic (18:1, 45–50%), linoleic (18:2, 13–15%), and linolenic (18:3, 1–2%) (22, 23). These fatty acids account for well over 90% of the fatty acids in human adipose tissue. Odd-carbon fatty acids, longer chain fatty acids, and shorter chain fatty acids account for the remainder. Each of these less-abundant fats individually contributes much less than 1% (22).

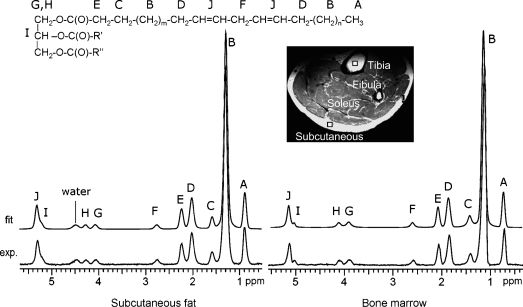

At 7 T, 10 resonances can be resolved, designated here as A to J in alphabetic order from upfield to downfield (Fig. 1). Six resonances contribute equivalent information about triglyceride composition: the CH3 methyl protons (labeled A, at ∼0.90 ppm), the CH2 methylene protons α- (E, at ∼2.25 ppm) and β- (C, at ∼1.59 ppm) to the carbonyl, and the glycerol backbone CH (I) and CH2 protons (G and H). Hence, there are only four additional informative resonances to consider: 1) bulk CH2 methylene protons (labeled B at ∼1.3 ppm); 2) allylic CH2 protons, α- to a double bond, at 2.03 ppm (D); 3) diallylic (also called bis-allylic) CH2 protons at 2.77 ppm (F); and 4) olefinic, double bond -CH = CH- protons at 5.31 ppm (J), which partially overlap with the glycerol CH methine proton at 5.21 ppm (I).

Fig. 1.

1H NMR spectra of subcutaneous fat (left) and tibial bone marrow (right) from a 26 year-old healthy male at 7 Tesla (7T). Ten resonances can be resolved (A–J). The bottom trace shows the acquired spectrum, and the upper trace shows the fitted spectrum. A water signal is seen in the spectrum of subcutaneous fat but not bone marrow. A T2-weighted image shows the position of the voxel in the subcutaneous fat tissue and tibial bone marrow (5 × 5 × 5 mm3) from which the spectra were acquired.

It was assumed that the fatty acids detected here contain either 0, 1, or 2 double bonds. These three types of fatty acids account for ∼97–98% of total fat in humans on ordinary Western diets. Linolenic acid (18:3) is excluded in this simplification, but it contributes only ∼0.5% of the total triglycerides (22). With this assumption, fsat + fmono + fdi = 1 where fsat, fmono, and fdi refer to the fraction of fatty acids that are saturated, monounsaturated, and doubly unsaturated (or diunsaturated), respectively. The fraction that is diunsaturated, fdi, can be determined directly from the relative area of the resonance of the “bridging” diallylic protons (resonance F), with respect to the resonance of methylene protons α to COO (resonance E):

|

Eq. 1 |

Once the fdi value is determined, one can evaluate fmono from the relative area of proton resonance α to the double bond by:

|

Eq. 2 |

The remaining unknown fsat, the fraction of saturated fatty acid, is derived as fsat = 1 − (fmono + fdi).

Assuming that f16C + f18C = 1, the fraction of fatty acids that are 16 carbon versus 18 carbon can be determined from the area of the bulk methylene resonances (-CH2-)n:

|

Eq. 3 |

The coefficients in front of the individual fractions are: 12 for palmitic acid (16:0), 8 for palmitoleic acid (16:1), 14 for stearic acid (18:0), 10 for oleic acid (18:1), and 7 for linoleic acid (18:2). This analysis is essentially identical to the earlier analysis (20) with the exception that a term for an unsaturated fat with three double bonds was omitted rather than assuming a low, fixed concentration.

RESULTS

Ten lipid resonances are typically observed in the 7T 1H spectrum from physiological fats (Fig. 1). Except for the double-bond protons, which partially overlap the methine proton of the glycerol backbone (the chemical shift difference is about 0.1 ppm), the lipid resonances were well-resolved at 7T and qualitatively similar to high-resolution spectra obtained in mice (20). The water signal generally appears in the 1H spectrum of subcutaneous fat tissue, with subject-dependent intensity and line width, but it is nearly undetectable in bone marrow acquired from a small voxel (∼0.1 ml). The resonance assignments, chemical shifts, and relative intensities from both marrow and subcutaneous fat are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Chemical shifts and relative resonance areas

| Resonance Areas

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter and Structure | Chemical Group | Chemical Shift | Marrow | Subcutaneous |

| ppm | ||||

| A (methyl protons) | -CH3 | 0.90 | 130.2 ± 11.3 | 125.8 ± 14.5 |

| B (methylene protons) | -(CH2)n- | 1.30 | 935.0 ± 59.2 | 956.4 ± 73.1 |

| C (methylene protons β to COO) | -CH2-CH2-COO | 1.59 | 104.5 ± 12.3 | 109.1 ± 15.4 |

| D (methylene protons α to C = C) | -CH2-CH = CH-CH2- | 2.03 | 141.7 ± 10.8 | 146.0 ± 15.2 |

| E (methylene protons α to COO) | -CH2-COO | 2.25 | 100 | 100 |

| F (diallylic methylene protons) | =CH-CH2-CH = | 2.77 | 24.5 ± 3.1 | 23.4 ± 3.9 |

| J (methine protons) | -CH = CH- | 5.31 | 62.4 ± 5.7 | 63.9 ± 6.2 |

The areas are relative to the methylene resonance α to COO (peak E) after correction for partial saturation. Resonance assignments by letter correspond to Fig. 1. Values are the mean ± 1 SD (n = 20).

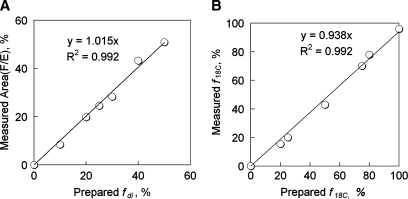

The validity of this analysis was tested by mixing three C18 triacylglycerols and, in a separate experiment, by mixing C16 and C18 triacylglycerols, in various ratios. Figure 2A shows data collected from phantoms, with the area (F/E) plotted against the actual known fraction of trilinolein (fdi) in the C18 mixture phantom samples. A linear correlation is seen between the measured F/E ratio and the sample true fdi value, with linear coefficient of 1.02 and correlation coefficient R2 = 0.992. Similar correlations were found for the other components (data not shown). Figure 2B shows the measured C18 triacylglycerol faction (f18C) against the actual known C18 fraction in the C16 and C18 mixture phantom samples. The plot of the known f18C versus the measured f18C, which was evaluated by 0.5 * area (B/E) − 12, also yielded a linear dependence, with linear coefficient of 0.94 and correlation coefficient R2 = 0.992.

Fig. 2.

A: Correlation of the known, prepared fraction of diunsaturated triglyceride with MR-measured fraction of diunsaturated triglyceride. Phantoms were prepared by mixing three C18 triglycerides (number of double bonds), tristearin (0), triolein (1), and trilinolein (2) in the following ratios (tristearin:triolein:trilinolein): 50:0:50, 50:10:40, 50:20:30, 50:30:20, 50:40:10, 50:50:0, and 25:50:25. 1H NMR spectra of the phantoms were analyzed using Equations 1 and 2. B: Correlation of the known, prepared fraction of C18 triglyceride with MR-measured value from area (B/E). Phantoms were prepared by mixing C16 tripalmitin and C18 tristearin with the following ratios (C16:C18): 100:0, 80:20, 75:25, 50:50, 25:75, 20:80, and 0:100. The data were analyzed using f18C = 0.5 * area (B/E) − 12.

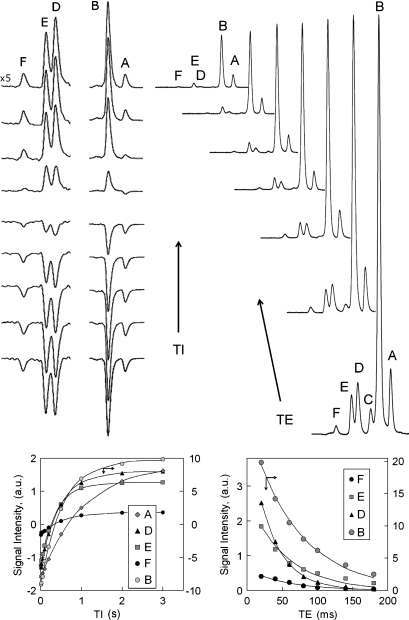

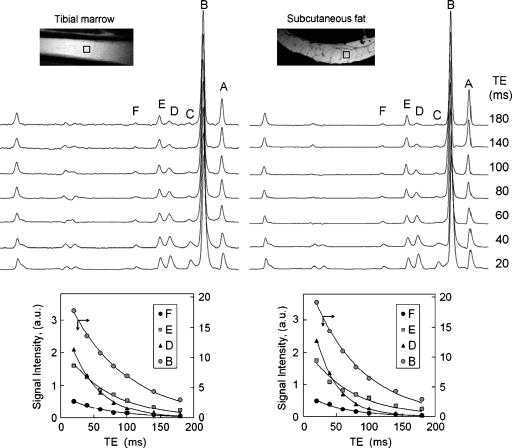

For quantitation of fat composition in human subcutaneous tissue and tibial marrow, the signal intensities were corrected for all differences in T1 and T2 as determined from inversion-recovery (Fig. 3) and TE-dependent (Fig. 4) experiments, respectively. Figure 3 shows the T1 (left) and T2 (right) spectra collected from the same voxel located in subcutaneous tissue, together with the corresponding curve fittings (bottom). Figure 4 compares the T2 data between tibial marrow and subcutaneous tissue collected from same-sized voxels, on the same volunteer. The measured T1 and T2 values at this field are summarized in Table 2. As shown by the data, protons at different structural positions in fats have quite different values, with T1s ranging from 0.32–1.16 s, and T2s ranging from 30–74 ms. Calf subcutaneous fat has shorter T1 and T2 values, about 7% on average, in comparison with tibial bone marrow. It should be pointed out that because of the presence of proton J-coupling, these T1 and T2 values are valid only for STEAM sequence. Shorter T2 values have been reported for animal abdominal fat using point-resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) sequence (20) at the same field strength.

Fig. 3.

Inversion-recovery measurement of T1 (left panel) and echo time (TE)-dependence measurement of T2 (right panel) from subcutaneous fat tissues of a 34 year-old healthy male at 7T. The inversion bandwidth (BW) was set to span resonances A and B (middle stack), or resonances C, D, E, and F (left-most stack). The inversion delay times for the given spectra are 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, and 3,000 ms with a constant repetition time (TR) of 7 s and TE of 40 ms (left panel). The echo times for the T2 measurements are 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 140, and 180 ms (right panel).

Fig. 4.

T2 measurement of tibia bone marrow (left panel) and calf subcutaneous fat (right panel) from a 25 year-old healthy female by varying TEs at 7T. Note that the voxel (5 × 5 × 5 mm3) fits well in the single fat cell of the subcutaneous tissue and the collected 1H spectrum is water-free. All spectra are vertically scaled to equal magnitude of the methylene resonance (B), and as a result, with TE increase, the methyl resonance A with longer T2 than B shows signal rising, whereas the shorter T2 resonances such as C and D show signal decaying relative to resonance B. To avoid overcrowding, the fitting of the “A” and “C” peaks is not shown. Other parameters: TR 8 s, number of acquisitions, 8; number of points, 4 k; BW 4 kHz.

TABLE 2.

Relaxation times in resonances assigned to the fatty acid chain (n = 3–6)

| T1, Second (n = 3)

|

T2, Milliseconds (n = 6)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Group | Marrow | Subcutaneous | Marrow | Subcutaneous |

| -CH3 (A) | 1.16 ± 0.04 | 1.08 ± 0.05 | 74 ± 6 | 67 ± 8 |

| -(CH2)n- (B) | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 69 ± 4 | 63 ± 5 |

| -CH2-CH2-COO (C) | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 33 ± 6 | 30 ± 6 |

| -CH2-CH = CH-CH2- (D) | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 42 ± 2 | 39 ± 3 |

| -CH2-COO (E) | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 60 ± 3 | 55 ± 4 |

| =CH-CH2-CH = (F) | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 59 ± 3 | 58 ± 3 |

The values shown are mean ± SD and are valid for the stimulated echo acquisition mode pulse sequence used.

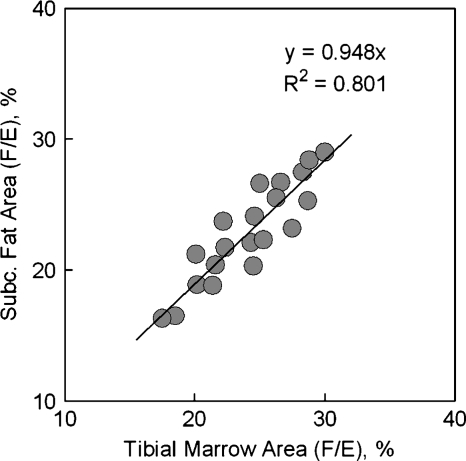

The derived fractions of saturated, monounsaturated and diunsaturated fat constituents are summarized in Table 3, together with the estimated fraction of fatty acid chain length f16C and f18C. The composition of bone marrow and adipose fat was not significantly different, with an average 29.1 ± 3.5% saturated, 46.4 ± 4.8% monounsaturated, and 24.5 ± 3.1% diunsaturated fractions for marrow, as compared with 27.1 ± 4.2% saturated, 49.6 ± 5.7% monounsaturated, and 23.4 ± 3.9% diunsaturated fractions for subcutaneous fat. A good linear correlation was seen between tibial marrow and subcutaneous fat in the measured area ratio (F/E), which is the index of diunsaturated fraction, for the 20 subjects studied, as shown in Fig. 5. In addition, a composition of 33.4 ± 4.9% from fatty acid with 16 carbons and 66.5 ± 9.7% from fatty acid with 18 carbons was calculated for bone marrow, as compared with subcutaneous fat with a composition of 23.4 ± 3.9% for 16 carbon fraction and 73.8 ± 17.8% for 18 carbon fraction.

TABLE 3.

Average fat composition in marrow and subcutaneous tissues

| Marrow | Subcutaneous | |

|---|---|---|

| Relative concentration | ||

| Saturated (fsat) | 29.1 ± 3.5 | 27.1 ± 4.2 |

| Monounsaturated (fmono) | 46.4 ± 4.8 | 49.6 ± 5.7 |

| Diunsaturated (fdi) | 24.5 ± 3.1 | 23.4 ± 3.9 |

| Chain length | ||

| Fraction 16-carbon (f16C) | 33.5 ± 4.9 | 26.2 ± 6.4 |

| Fraction 18-carbon (f18C) | 66.5 ± 9.7 | 73.8 ± 17.9 |

The relative concentration, as percentage of saturated, monounsaturated, and diunsaturated fats, as well as the fraction of 16- vs. 18-carbon fats are shown. Values are the mean ± 1 SD (n = 20).

Fig. 5.

Correlation of measured area (F/E) between tibial bone marrow and subcutaneous fat for the 20 healthy adult subjects studied, showing that the diunsaturated fatty acid is similar for these two adipose sites and that the fat composition variation among subjects is detectable by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

DISCUSSION

High-quality 1H NMR spectra from human adipose tissue were obtained routinely at 7T. The features of the 1H spectra at 7T were consistent with spectra of triacylglycerols obtained under high-resolution conditions (8–12) or in mice at 7T (20). Perhaps the most significant observation was that chemical shift dispersion in humans is greatly improved compared with 1.5 T or 3.0 T. The ability to resolve protons adjacent to double bonds allows noninvasive estimation of the fatty acid composition of adipose tissue.

Proton-decoupled 13C NMR of human adipose tissue (15–19) allows more-detailed characterization of fat composition, compared with a 1H spectrum. For example, the outer unsaturated carbons in a bisallylic group (-CH2-CH = CH-CH2-CH = CH-CH2-) are resolved from the inner carbons in spectra obtained in vivo at 1.5 T. Natural abundance 13C NMR is limited by relatively low sensitivity, low spatial resolution and additional technical requirements, all disadvantages compared with 1H spectroscopy for human study. Conversely, 7T instruments are not widely available. However, because the number of 7T instruments in medical sites is increasing steadily and 1H spectroscopy is routine on all systems, it seems reasonable to anticipate use of 1H spectroscopy at 7T for clinical research.

At 7T, ten proton resonances in the chemical shift span of 0.9–5.3 ppm are resolved. The three resonances in the narrow range of 2.03–2.77 ppm provide an internal standard plus information about the abundance of protons between or adjacent to double bonds. This information, after correction for relaxation, allows calculation of the relative concentration of saturated, monounsaturated, and diunsaturated fatty acids. The proposed analysis of lipid composition was confirmed by comparison to authentic standards.

The fraction of saturated fats in triglycerides as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy at 7T, about 27–29%, is in excellent agreement with literature values. However, the fraction of fatty acids that are monounsaturated was somewhat less (about 46–50%) in this study, compared with biopsy studies, where about 55–60% monounsaturated fatty acids are typically found (22, 24). Consequently, the fraction of fatty acids estimated to be diunsaturated was about 23–24% in this study compared with about 17–18% in biopsy studies.

At least three technical issues may contribute error in this analysis. First, macromolecules or aqueous metabolites with chemical shifts overlapping the lipid resonances may alter the estimates of relative intensity. Second, the signals in vivo are the sum of very complex 1H spin-coupled multiplets from several different fatty acids with slightly different chemical shifts. Consequently, a single Lorentzian-Gaussian line does not properly represent the observed lineshape. Even when high-resolution analytical 1H NMR was used to measure marrow fat composition from samples extracted in chloroform, thereby removing aqueous species and other complicating factors that may contribute error in the study of intact tissue, the NMR method overestimated the fraction of saturated fatty acids, compared with “gold standard” gas chromatography of the same samples (12). Third, as emphasized earlier (20), correction for T2 is also essential and more important than correction for T1 differences. For a typical TE of 11 ms, the relative difference in T2 correction among the resonances D, E, and F accounts for ∼4%, but it reaches 8% at TE = 20 ms, and is as large as 18% at TE = 40 ms. This compares to only about 1% difference after correction for T1 effects for the same three resonances at TR = 2 s. The T1 correction is not needed when the spectrum is collected with TR of 4 s. It is found that the calf subcutaneous fat has relatively shorter (∼7%) proton relaxation times than the marrow (Table 2), indicating a larger local Bo field inhomogeneity on subcutaneous tissue. This can be understood from the difference in the microscopic structure between these two types of adipose tissues, as shown in the MRI images (Fig. 4, insert), in which subcutaneous tissue is seen as packed with large fat cells of different sizes, embedded with rich vasculature, and curvedly shaped, whereas the bone marrow appears as fine uniform structure, aligned straight inside the tibial bone, and nearly parallel to the Bo field. Because of this, the spectral resolution from bone marrow is generally superior to that from subcutaneous fat, as shown in Fig. 1.

It is probably unrealistic to anticipate perfect correlation between this MR analysis of extremity fat and marrow compared with literature data obtained largely from the abdomen, chest, or buttocks. There are complex effects of diet, season, gender, and anatomical site on fatty acid composition (24, 25). For example, extremity adipose tissue has a greater fraction of monounsaturated fat and less saturated fat compared with subcutaneous fat from the chest and abdomen (25). These factors were not controlled in the current study. Nevertheless, the average ratio fdi/fmono (47% for subcutaneous fat and 53% for bone marrow, Table 3) obtained from this 1H MRS study for 20 adult subjects (average age 34), is in excellent agreement with a previously reported value (50%) for the ratio of polyunsaturated to monounsaturated fatty acid by in vivo 13C study (19) of calf subcutaneous tissue of 17 adult subjects (average age 30). The obvious advantage of 1H MRS is that it is fast (less than 1 min), has a low specific absorption rate (no need for broadband decoupling as in 13C), is easily localized (not a volume detection), and is typically more easily implemented (no special scanner hardware or coil required). The high resolution and sensitivity of the current STEAM-based 1H MR analysis also enable the detection of fat composition variation among uncontrolled healthy subjects (Fig. 5), which might be attributed to the difference in individuals’ long-term diet and metabolic genetics. Therefore, it is anticipated that the method may be useful in rapid detection of substantial changes in the composition of fatty acids in response to diet, exercise, and fat-metabolic diseases. This method, in our view, would help advance noninvasive human lipid research, which has been focused on studying fat mass distribution by MRI and other techniques rather than fat molecular structural composition. In addition, an analysis of our data (not shown) indicates no obvious difference in fat composition between male and female subjects, although, on average, the calf subcutaneous fat in female is approximately two-fold thicker than in male.

The decision to simplify the description of fatty acid composition to saturated, monounsaturated, and diunsaturated fats was based on two considerations. First, the amount of polyunsaturated fats (three or more double bonds) in human adipose tissue contributes very little, less than 1–2%, to the total 1H NMR signal. Second, earlier studies that were able to quantify triply unsaturated fatty acids separate from other fatty acids required high-resolution analytical conditions (10–12). For practical purposes in humans, this achievement would mean the capacity to separately quantify oleic (18:1), linoleic (18:2), and linolenic (18:3) acid. However, at the resolution achieved in these studies, a 50:50 mixture of triolein:trilinolenin is indistinguishable from a spectrum of trilinolein. For these reasons, the description of fatty acids as saturated, monounsaturated, or diunsaturated seems a reasonable simplification.

Frequency-dependent spatial localization introduces a chemical shift displacement artifact in the 1H MR spectrum. Quantitation may be inaccurate if it is based on ratios of two resonances when the region of interest is close to the inter-tissue boundary. Although this effect was not critically evaluated in this study, the use of a small voxel (∼0.1 ml) well within the bone marrow plus analysis of resonances over a narrow chemical shift range reduces susceptibility to chemical shift displacement effects. Unlike the methyl resonance, the resonance of protons α to the carbonyl is not affected by the neighboring large bulk CH2 (resonance B), which often induces an uneven baseline at nearby resonances at shorter TEs. Although this baseline problem can be improved at longer TEs, the faster decay of protons α to a double bond (resonance D, T2 = 42 ms for marrow, and 39 for subcutaneous fat) than the reference resonance E (T2 = 59 ms) makes long TE scan conditions less favorable. STEAM sequence has the advantage of shorter TE than PRESS and less dependence on proton J modulation due to the smaller TE/T2 ratio, and therefore was chosen for the quantification of fat composition in this method.

In addition to composition analysis, the well-resolved resonances of human tibial bone marrow and calf subcutaneous fat at 7T could also be very useful as an internal standard to quantify intramuscular lipids (26), which have attracted great research interest over the last few years, owing to their relation to insulin sensitivity, diabetes, and obesity (27).

In conclusion, this 1H MRS study at 7T indicates that the rapid acquisition of high-quality 1H NMR spectra from subcutaneous fat and from bone marrow is straightforward in healthy volunteers, and that the spectra may be analyzed to assess triglyceride composition. This may facilitate longitudinal monitoring of changes in lipid composition in response to diet, exercise, and disease.

Abbreviations

BW, bandwidth

MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy

NA, number of acquisitions

NP, number of points

PRESS, point-resolved spectroscopy

STEAM, stimulated echo acquisition mode

7T, 7 Tesla

TE, echo time

TR, repetition time

Published, JLR Papers in Press, May 28, 2008.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant RR-02584) and the Department of Defense (Contract number W81XWH-06-2-0046).

References

- 1.Simonsen N., P. van't Veer, J. J. Strain, J. M. Martin-Moreno, J. K. Huttunen, J. F. Navajas, B. C. Martin, M. Thamm, A. F. Kardinaal, F. J. Kok, et al. 1998. Adipose tissue omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid content and breast cancer in the EURAMIC study. European Community Multicenter Study on Antioxidants, Myocardial Infarction, and Breast Cancer. Am. J. Epidemiol. 147 342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shannon J., I. B. King, R. Moshofsky, J. W. Lampe, D. Li Gao, R. M. Ray, and D. B. Thomas. 2007. Erythrocyte fatty acids and breast cancer risk: a case-control study in Shanghai, China. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85 1090–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storlien L. H., J. A. Higgins, T. C. Thomas, M. A. Brown, H. Q. Wang, X. F. Huang, and P. L. Else. 2000. Diet composition and insulin action in animal models. Br. J. Nutr. 83 (Suppl.): 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manco M., A. V. Greco, E. Capristo, D. Gniuli, A. De Gaetano, and G. Gasbarrini. 2000. Insulin resistance directly correlates with increased saturated fatty acids in skeletal muscle triglycerides. Metabolism. 49 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storlien L. H., A. B. Jenkins, D. J. Chisholm, W. S. Pascoe, S. Khouri, and E. W. Kraegen. 1991. Influence of dietary fat composition on development of insulin resistance in rats. Relationship to muscle triglyceride and omega-3 fatty acids in muscle phospholipid. Diabetes. 40 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer K. A., L. H. Kushi, D. R. Jacobs, Jr., and A. R. Folsom. 2001. Dietary fat and incidence of type 2 diabetes in older Iowa women. Diabetes Care. 24 1528–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu F. B., and W. C. Willett. 2002. Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 288 2569–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zancanaro C., R. Nano, C. Marchioro, A. Sbarbati, A. Boicelli, and F. Osculati. 1994. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy investigations of brown adipose tissue and isolated brown adipocytes. J. Lipid Res. 35 2191–2199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyake Y., K. Yokomizo, and N. Matsuzaki. 1998. Determination of unsaturated fatty acid composition by high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 75 1091–1094. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillen M. D., and A. Ruiz. 2003. 1H nuclear magnetic resonance as a fast tool for determining the composition of acyl chains in acylglycerol mixtures. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 105 502–507. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knothe G., and J. A. Kenar. 2004. Determination of the fatty acid profile by 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 106 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeung D. K. W., S. L. Lam, J. F. Griffith, A. B. W. Chan, Z. Chen, P. H. Tsang, and P. C. Leung. 2008. Analysis of bone marrow fatty acid composition using high-resolution proton NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 151 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lunati E., P. Farace, E. Nicolato, C. Righetti, P. Marzola, A. Sbarbati, and F. Osculati. 2001. Polyunsaturated fatty acids mapping by 1H MR-chemical shift imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 46 879–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velan S. S., C. Durst, S. K. Lemieux, R. R. Raylman, R. Sridhar, R. G. Spencer, G. R. Hobbs, and M. A. Thomas. 2007. Investigation of muscle lipid metabolism by localized one- and two-dimensional MRS techniques using a clinical 3T MRI/MRS scanner. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 25 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckmann N., J. J. Brocard, U. Keller, and J. Seelig. 1992. Relationship between the degree of unsaturation of dietary fatty acids and adipose tissue fatty acids assessed by natural-abundance 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy in man. Magn. Reson. Med. 27 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimand R. J., C. T. Moonen, S. C. Chu, E. M. Bradbury, G. Kurland, and K. L. Cox. 1988. Adipose tissue abnormalities in cystic fibrosis: noninvasive determination of mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids by carbon-13 topical magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Pediatr. Res. 24 243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moonen C. T., R. J. Dimand, and K. L. Cox. 1988. The noninvasive determination of linoleic acid content of human adipose tissue by natural abundance carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance. Magn. Reson. Med. 6 140–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas E. L., G. Frost, M. L. Barnard, D. J. Bryant, S. D. Taylor-Robinson, J. Simbrunner, G. A. Coutts, M. Burl, S. R. Bloom, K. D. Sales, et al. 1996. An in vivo 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopic study of the relationship between diet and adipose tissue composition. Lipids. 31 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang J. H., S. Bluml, A. Leaf, and B. D. Ross. 2003. In vivo characterization of fatty acids in human adipose tissue using natural abundance 1H decoupled 13C MRS at 1.5 T: clinical applications to dietary therapy. NMR Biomed. 16 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strobel K., J. van den Hoff, and J. Pietzsch. 2008. Localized proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of lipids in adipose tissue at high spatial resolution in mice in vivo. J. Lipid Res. 49 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lund P., D. Abadi, and J. Mathies. 1962. Lipid composition of normal human bone marrow as determined by column chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 3 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Field C. J., A. Angel, and M. T. Clandinin. 1985. Relationship of diet to the fatty acid composition of human adipose tissue structural and stored lipids. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 42 1206–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malcom G. T., A. K. Bhattacharyya, M. Velez-Duran, M. A. Guzman, M. C. Oalmann, and J. P. Strong. 1989. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue in humans: differences between subcutaneous sites. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 50 288–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beynen A. C., R. J. Hermus, and J. G. Hautvast. 1980. A mathematical relationship between the fatty acid composition of the diet and that of the adipose tissue in man. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 33 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriya K., and S. Itoh. 1969. Regional and seasonal differences in the fatty acid composition of human subcutaneous fat. Int. J. Biometeorol. 13 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weis J., L. Johansson, F. Ortiz-Nieto, and H. Ahlström. 2008. Assessment of lipids in skeletal muscle by high-resolution spectroscopic imaging using fat as the internal standard: Comparison with water referenced spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Med. 59 1259–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodpaster B. H., and D. Wolf. 2004. Skeletal muscle lipid accumulation in obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes. 5 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]