Abstract

In angiosperms, germination represents an important developmental transition during which embryonic identity is repressed and vegetative identity emerges. PICKLE (PKL) encodes a CHD3-chromatin remodeling factor necessary for the repression of expression of LEAFY COTYLEDON1 (LEC1), a central regulator of embryogenesis. A candidate gene approach and microarray analysis identified nine additional genes that exhibit PKL-dependent repression of expression during germination. Transcripts for all three LEAFY COTYLEDON genes, LEC1, LEC2, and FUS3, exhibit PKL-dependent repression, and all three transcripts are elevated more than 100-fold in pkl primary roots that inappropriately express embryonic traits (“pickle roots”). Three other genes that exhibit PKL-dependent regulation have expression patterns correlated with zygotic or somatic embryogenesis, and one gene encodes a putative LIM domain transcriptional regulator that is preferentially expressed in siliques. Genes that exhibit PKL-dependent repression during germination are not necessarily regulated by PKL at other points in development. Our data suggest that PKL selectively regulates a suite of genes during germination to repress embryonic identity. In particular, we propose that PKL acts as a master regulator of the LEAFY COTYLEDON genes, and that joint derepression of these genes is likely to contribute substantially to expression of embryonic identity in pkl seedlings.

Keywords: CHD3, chromatin remodeling factors, developmental transition, embryo, seed, germination

INTRODUCTION

The germination of a seed is a dramatic developmental event that is dependent on the plant growth regulators gibberellin (GA) and abscisic acid (ABA) and on multiple other factors (Koornneef et al., 2002). In the pkl mutant of Arabidopsis, this developmental transition is perturbed; pkl seedlings continue to express embryonic identity after germination (Ogas et al., 1997). PKL is predicted to encode a member of the CHD3 family of chromatin remodeling proteins (Eshed et al., 1999; Ogas et al., 1999) suggesting that the inability of pkl seedlings to repress embryonic identity is a result of a defect in transcriptional regulation. The name ‘CHD’ is derived from the predicted domain structure of these proteins, which includes two copies of a chromatin organization modifier domain (chromodomain), a SWI/SNF - ATPase domain, and a motif with sequence similarity to a DNA-binding domain (Woodage et al., 1997). In addition to these domains, CHD3 proteins also contain one or more plant homeodomain (PHD) zinc fingers.

Ongoing work with CHD3 proteins in animal systems indicates that CHD3 proteins mediate transcriptional repression and that they play specific roles in development (Ahringer, 2000). A CHD3 protein is a component of the multisubunit Mi-2/NURD complex, a major histone deacetylation complex in Xenopus and mammalian cell lines that possesses nucleosome remodeling activity (Tong et al., 1998; Wade et al., 1998; Xue et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998). This complex is hypothesized to play a role in establishment and/or maintenance of hypoacetylated domains of chromatin that result in transcriptional repression of target genes. Drosophila that are homozygous for a mutation in the CHD3-encoding gene dMi-2 die at the first or second larval instar (Kehle et al., 1998). dMi-2 and the corresponding CHD3 protein have been shown to interact genetically and physically with key transcriptional regulators of embryo development and neuronal cell fate determination (Kehle et al., 1998; Murawsky et al., 2001). In particular, dMi-2 binds to the gap protein Hunchback and participates in the repression of the homeotic HOX genes (Kehle et al., 1998). Thus, dMi-2 appears to function as a transcriptional repressor that is recruited to different promoters through interaction with a number of proteins and plays a role in several developmental pathways. In a similar vein, C. elegans Mi-2 genes are necessary for the proper specification of developmental identity in vulval cell precursors (Solari et al., 2000; von Zelewsky et al., 2000).

Phenotypic characterization of the pkl mutant reveals that CHD3-chromatin remodeling factors also play a role in plant development. PKL is necessary for the repression of embryonic identity in Arabidopsis seedlings (Ogas et al., 1997; Ogas et al., 1999). The most striking phenotype of pkl seedlings is the presence of large, swollen primary roots (referred to as pickle roots) that express many embryonic characteristics, including the ability to undergo somatic embryogenesis. GA represses the expression of the pickle root phenotype. Furthermore, the ability of GA to repress penetrance of the pickle root phenotype is restricted to the developmental period of 24 to 36 h following imbibition (seed wetting) (Ogas et al., 1997). Thus PKL and GA function early during germination to prevent the misexpression of embryonic identity that is evident later in seedling development.

Characterization of gene expression in pkl mutants suggests that PKL acts as a negative regulator of transcription, analogous to animal CHD3 proteins. Expression of LEC1, a key promoter of embryonic identity that is normally expressed only in seeds (Lotan et al., 1998; Meinke, 1992), is derepressed in the pkl mutant during germination (Ogas et al., 1999). Furthermore, the LEC1 transcript is elevated during the time at which derepression of embryonic identity in pkl seedlings has been shown to be dependent on GA, suggesting that LEC1 may be a direct target of PKL.

The objective of this study was the identification of other genes that might contribute to derepression of embryonic identity in pkl seedlings. Examination of candidate gene expression and analysis of microarrays identified nine additional genes that exhibited robust PKL-dependent repression of expression during germination, five of which have been previously associated with embryogenesis. The data suggest that PKL selectively represses key promoters of embryonic identity during germination so that vegetative identity can become fully established in the developing Arabidopsis seedling.

RESULTS

PKL regulates expression of LEC2 in germinating seeds

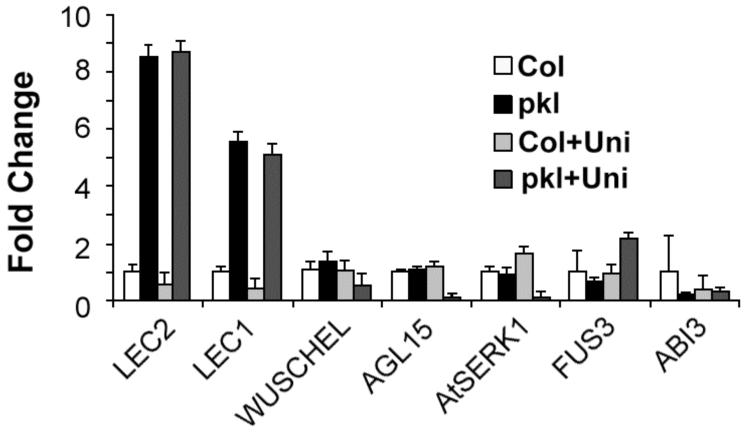

We examined whether other genes associated with zygotic or somatic embryogenesis exhibited PKL-dependent repression similar to LEC1. We examined the expression of all three LEC genes, LEC1 (Lotan et al., 1998), LEC2 (Stone et al., 2001), and FUS3 (Luerssen et al., 1998), as well as another master regulator involved in embryo maturation ABI3 (Giraudat et al., 1992). We looked at the expression of another transcriptional regulator, AGL15 (Heck et al., 1995), that is preferentially expressed in embryos but for which a corresponding loss-of-function allele has yet to be phenotypically characterized. We also examined the expression of two genes that promote somatic embryogenesis when overexpressed, AtSERK1 (Hecht et al., 2001) and WUSCHEL (Zuo et al., 2002). These genes were not meant to be an exhaustive list of genes associated with embryogenesis but rather a representative selection with which we could address the generality of PKL-dependent repression.

We examined the relative transcript level of these genes in germinating seeds that were developmentally staged such that 50% of the seeds had cracked seed coats. This developmental stage was selected based on our previous characterization of the behavior of LEC1 transcript in germinating pkl seed (Ogas et al., 1999). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using total RNA from wild-type and pkl seed imbibed in either the absence or presence of uniconazole-P, an inhibitor of GA biosynthesis (Izumi et al., 1985). We examined whether or not transcript levels were dependent on uniconazole-P to address the possibility that altered expression of one or more of these genes might contribute to the increased penetrance of the pickle root phenotype that is observed when pkl seeds are germinated in the presence of uniconazole-P (Ogas et al., 1997).

We observed that transcript levels of both LEC1 and LEC2 were greatly increased in germinating pkl seeds (Figure 1). The LEC2 transcript was elevated more than 8-fold in germinating pkl seeds relative to germinating wild-type seeds, whereas the LEC1 transcript was elevated more than 5-fold. The mRNA level of both genes was largely insensitive to uniconazole-P. Although other studies have shown that the LEC2 transcript was present during germination (Stone et al., 2001) and that the LEC1 transcript was not (Lotan et al., 1998; Ogas et al., 1999), qRT-PCR analysis revealed that transcripts for both genes are present during germination. The FUS3 transcript was only elevated in pkl seeds imbibed in the presence of uniconazole-P. Subsequent analyses, however, revealed that the level of the FUS3 transcript is also PKL-dependent in the absence of uniconazole-P when assayed at a later stage of development (100% germination versus 50% cracked seed coats; see below). Thus the transcript level of all three LEC genes is PKL-dependent.

Figure 1.

LEC1 and LEC2 transcripts are elevated in germinating pkl seeds. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the relative transcript levels of the genes of interest in germinating wild-type and pkl seeds in the absence or presence of uniconazole-P. The transcripts examined represent genes known or suspected to be involved in embryogenesis (see text). 18s rRNA was used as a standardization control, and expression levels are normalized to wild-type seeds imbibed in the absence of uniconazole-P. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

Expression of the other candidate genes was largely PKL- and uniconazole-P-insensitive, with the notable exception of AGL15 and AtSERK1. Surprisingly, the mRNA level of both of these genes is substantially reduced (> 10-fold) in germinating pkl seeds if they are imbibed in the presence of uniconazole-P (Figure 1). Thus expression of both of these putative positive regulators of embryonic identity is decreased under conditions that lead to increased expression of the pickle root phenotype. Although this result suggests that AGL15 and AtSERK1 do not contribute to expression of the pickle root phenotype, a loss-of-function mutation in these genes would be necessary to test this hypothesis. Such a loss-of-function mutation has not been described for either of these loci. The level of ABI3 and WUSCHEL transcripts (Figure 1) are not PKL-dependent at this point in development. Consequently, altered expression of these genes is unlikely to contribute to determination of the potential to express embryonic identity in pkl seedlings.

Microarray analysis reveals additional genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression

The finding that two known master regulators of embryonic identity (LEC1 and LEC2) exhibit PKL-dependent expression relatively early in germination whereas another well-characterized regulator (ABI3) does not was consistent with our hypothesis that PKL acts to repress certain genes that promote embryonic identity. To identify additional putative targets of PKL, we utilized oligonucleotide-based microarrays from Affymetrix that represent 8256 genes covering approximately 30% of the Arabidopsis thaliana transcriptome. We examined transcript levels in pkl and wild-type seeds imbibed in the presence or absence of uniconazole-P until 50% of the seeds had cracked seed coats as above. A portion of seeds from each treatment was retained to determine germination percentages, and to determine the effect that uniconazole-P had on pickle root penetrance. Greater than 99% of the seeds germinated and became seedlings for all treatments. Pickle root penetrance increased from 7.1% on MS media to 59.4% on MS media supplemented with uniconazole-P. The microarray experimental design then consisted of four treatments: untreated wild type (Wt), untreated pkl mutant (Pkl), uniconazole-P treated wild type (Uwt) and uniconazole-P treated pkl mutant (Upkl). There were four replications per treatment, for a total of 16 microarrays.

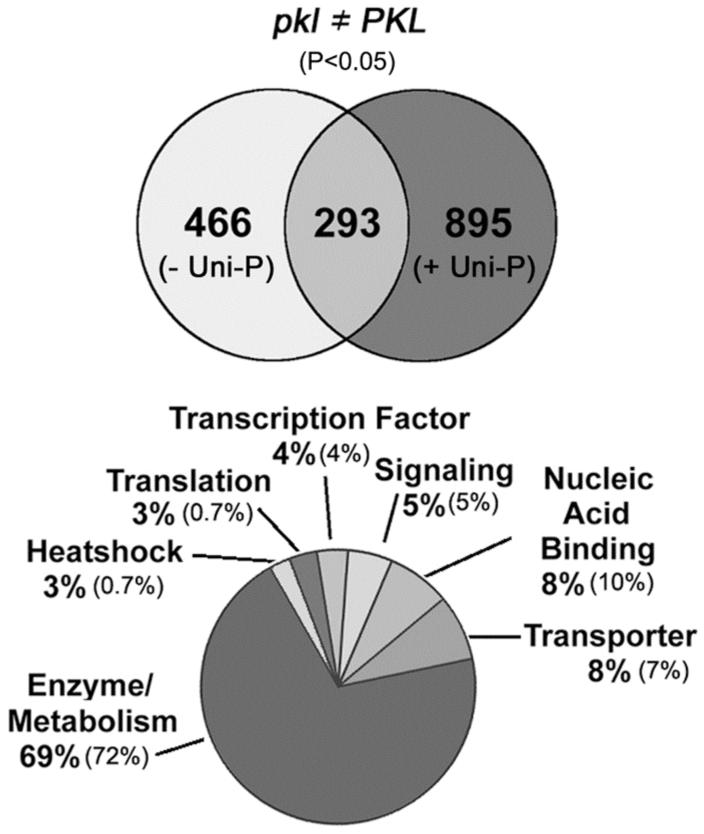

Our analyses of LEC1 and LEC2 revealed that expression of these genes is strongly derepressed in pkl seeds and unaffected by uniconazole-P treatment (Figure 1). Based on these results, we queried our data set for genes that exhibited altered expression in germinating pkl seeds regardless of uniconazole-P treatment. We compared expression values using the t-test.

The t-test criterion (p < 0.05) identified 759 genes that were expressed at different levels in wild-type and pkl seeds on MS media. For pkl and wild-type seeds imbibed on MS media supplemented with uniconazole-P the same criterion identified 1188 genes. We took the intersection of the two sets of genes described (293 genes). A Venn diagram depicting this intersection is shown in Figure 2. Of the genes represented by the intersection, 185 had higher transcript levels in pkl seeds in the presence or absence of uniconazole-P whereas 101 genes had decreased transcript levels (see http://www.biochem.purdue.edu/research/ogas_lab/arrays/). The subset of genes identified by this analysis as exhibiting PKL-dependent expression represented a little more than 3.5% of the total number of elements present on the array. Among the genes that code for a protein with a known or putative function (158), there was little change in the relative abundance of the basic types of protein function represented on the arrays overall, with the exception of heat shock proteins and proteins involved in translation (Figure 2). The percentage of both of these functional classes was found to be increased approximately four-fold among genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression when compared to their representation among all of genes found on the microarrays.

Figure 2.

Identification of genes that exhibit PKL-dependent transcript levels. The Venn diagram (top) indicates the number of loci for which the corresponding transcript is expressed at significantly different (p < 0.05) levels in wild-type (PKL) versus pkl seeds in the absence (- Uni-P) or presence (+ Uni-P) of uniconazole-P. The intersection of both data sets represents the 293 genes that showed significantly different expression (p < 0.05, uncorrected for multiple comparisons) in the pkl mutant regardless of the presence of uniconazole-P. The 293 genes constituted about 3.5% of the total number of loci interrogated with the array, and 54% of the genes identified have a known or putative function. Functional categories assigned to the 54% with known or putative functions are represented in the chart at the bottom. The smaller number in parentheses indicates the percentage of all of the genes represented on the microarray that were assigned to that functional category.

The LEC1 and LEC2 transcripts are elevated 4-fold or more in pkl seeds in both the absence and presence of uniconazole-P when assayed by qRT-PCR (Figure 1). Of the 185 genes with increased mRNA levels in pkl seed identified by microarray analysis, transcripts of 56 were elevated two-fold or more in pkl seeds in both the absence and presence of uniconazole-P. Based on this similarity of expression pattern, these genes were considered to be strong candidates for genes whose expression might show a dependence on PKL analogous to that of LEC1 and LEC2.

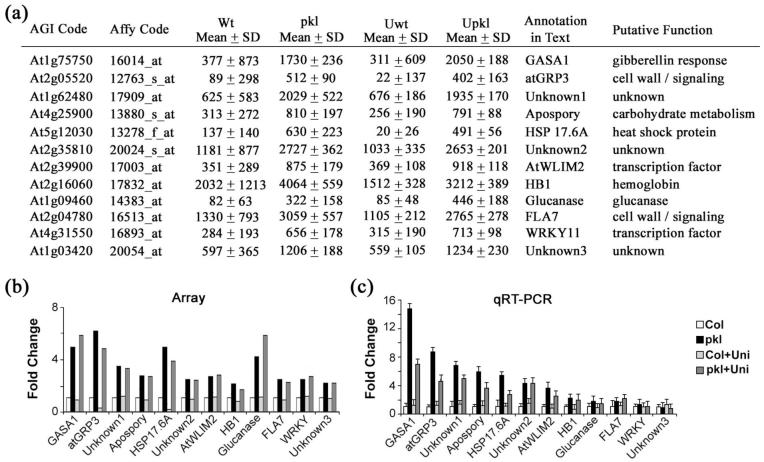

We wished to verify that a subset of these genes exhibited PKL-dependent expression when assayed by an alternative method and then follow expression of these genes under several other conditions to explore the potential role of these genes in embryo development and in generation of pkl-associated phenotypes. Although it was tempting to pick genes based on putative function - transcriptional regulators for example - we were concerned that this approach might lead to an inaccurate assessment of the validity of the methods we used to identify the 56 genes from the microarray dataset. We therefore randomly selected 12 of the 56 genes (Figure 3a) for further analysis for an unbiased test of the value of our selection criteria.

Figure 3.

Transcript level of several genes is strongly PKL-dependent during germination. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the relative transcript levels of the genes of interest in germinating wild-type and pkl seeds in the absence or presence of uniconazole-P. The transcripts examined represent twelve genes that exhibit robust PKL-dependent expression based on microarray analysis (see text).

(a) Microarray data for the twelve candidate genes that were analyzed. Both the AGI code and the corresponding Affymetrix identification code are given. The mean values derived from the microarray analysis for these genes under the four treatments are shown. The last two columns indicate the name of the gene as referred to in the text of this paper along with the predicted function of the gene based on published data and/or sequence similarity.

(b) Relative transcript levels of the twelve genes as indicated by microarray analysis. Expression levels are normalized to wild-type seeds imbibed in the absence of uniconazole-P.

(c) Relative transcript levels of the twelve genes as indicated by quantitative RT-PCR. 18s rRNA was used as a standardization control, and expression levels are normalized to wild-type seeds imbibed in the absence of uniconazole-P. Genes are ordered by relative expression in pkl seeds from highest to lowest from left to right. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

We re-examined the transcript levels for these 12 genes by qRT-PCR using the same total RNA pools from germinating seeds that were used for microarray analysis (Figure 3c). We found that transcripts of eight of the genes were significantly (p < 0.05) elevated in pkl seeds by qRT-PCR. Thus independent experimental verification of our candidates suggests that approximately 2/3 of the genes that we identified by microarray analysis will exhibit PKL-dependent expression when assayed by another means.

Transcripts of seven of the genes that we assayed were elevated by at least 4-fold in pkl seeds relative to wild-type seeds (Figure 3c). Thus the expression of these genes when assayed by qRT-PCR is dependent on PKL to an extent that is comparable to that of LEC1 and LEC2. We decided to follow expression of these 7 genes and LEC1 and LEC2 to determine if the 9 genes exhibited similar transcriptional regulation under other conditions. We also included FUS3 in this analysis based on the observation that the FUS3 transcript was elevated in pkl seeds treated with uniconazole-P (Figure 1) and the fact that FUS3 is also a LEC gene (Keith et al., 1994; Meinke et al., 1994).

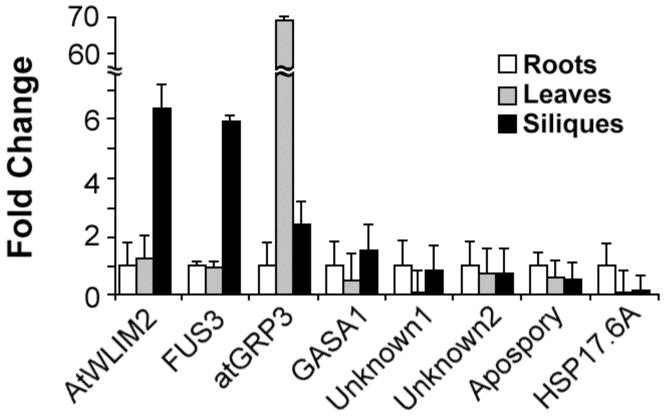

The LIM domain transcription factor is preferentially expressed in developing siliques

We wished to test the possibility that one or more of the seven genes that exhibit at least a 4-fold elevation of transcript level in pkl seeds might be preferentially expressed in developing seeds in a manner analogous to LEC1, LEC2, or FUS3 (Lotan et al., 1998; Luerssen et al., 1998; Stone et al., 2001). Such a result would be consistent with the hypothesis that one or more of these genes might function as a positive regulator of embryonic identity analogous to the LEC genes. We therefore examined the relative abundance of transcripts in wild-type roots, leaves, and developing siliques using qRT-PCR (Figure 4). We included FUS3 in this analysis as a positive control. We found that one gene (At2g39900) was preferentially expressed in siliques in a manner similar to FUS3, suggesting that it might also be involved in embryo development. This gene, previously identified as AtWLIM2, is predicted to encode a LIM domain transcription factor (Eliasson et al., 2000). At2g05520, which encodes the glycine rich protein atGRP3, was preferentially expressed in leaves as observed previously (de Oliveira et al., 1990). The remaining genes did not show significant changes in transcript levels in the tissues examined.

Figure 4.

The LIM-encoding gene is preferentially expressed in siliques. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the relative transcript levels of the genes of interest in wild-type roots, rosette leaves, and siliques. The transcripts examined represent genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression during germination. Genes are ordered by relative expression in siliques from highest to lowest from left to right. 18s rRNA was used as a standardization control, and expression levels are normalized to roots. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

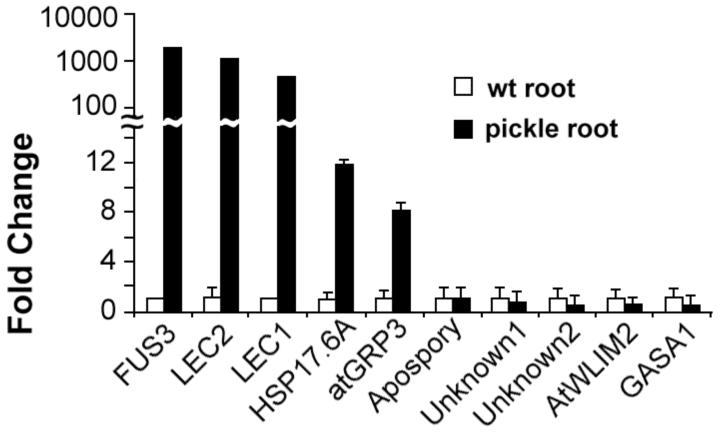

Some genes that exhibit PKL-dependent regulation during germination are highly expressed in pickle roots

To determine if the gene expression that is derepressed during germination in pkl mutant seeds is also elevated in pickle roots, we compared transcript levels in wild-type roots (non embryonic) to pickle roots (embryonic). If the transcript level of a gene was found to be elevated in a pickle root, this result would suggest that altered expression of the gene might play a role in maintenance of pickle root identity.

Among the eleven genes examined, transcripts for LEC1, LEC2, FUS3, HSP 17.6A and atGRP3 are significantly elevated in pickle roots. qRT-PCR was performed using total RNA isolated from wild-type roots and pickle roots with gene-specific primers for the gene of interest (Figure 5). The LEC1, LEC2, and FUS3 transcripts were each elevated more than 100-fold in pickle roots in comparison to wild-type roots. LEC1, LEC2, and FUS3 encode transcriptional regulators that promote embryogenesis during both morphogenesis and maturation (Harada, 2001). Thus their enhanced expression in pickle root tissue is consistent with their known roles in promotion of embryonic identity. The transcripts for HSP 17.6A and atGRP3 were elevated approximately 12-fold and 8-fold respectively in pickle root tissue, an expression pattern consistent with previous observations. The HSP 17.6A transcript is elevated in maturing seeds (Sun et al., 2001), and increased transcript levels for GRPs are correlated with somatic embryogenesis (Magioli et al., 2001; Sato et al., 1995). The other six genes did not have significantly higher transcript levels in pickle roots. This observation indicates that PKL is not constitutively required to maintain proper transcript levels of these six genes. Furthermore, although altered expression of these genes may play a role in establishment of pickle root identity, altered expression is apparently not required for maintenance of pickle root identity.

Figure 5.

The LEC genes are highly expressed in pickle roots. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the relative transcript levels of the genes of interest in wild-type roots and pickle roots. The transcripts examined represent genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression during germination. Genes are ordered by relative expression in pickle roots from highest to lowest from left to right. 18s rRNA was used as a standardization control, and expression levels are normalized to wild-type roots. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

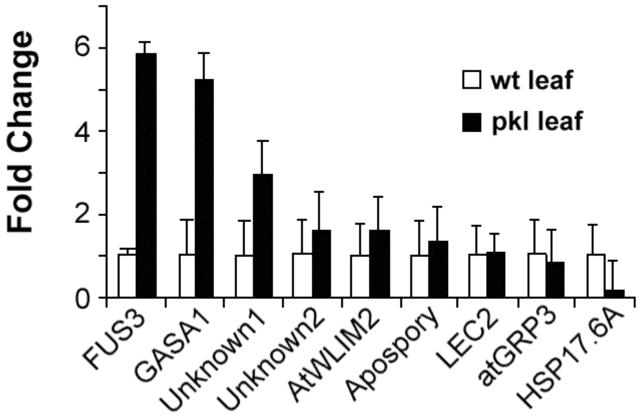

PKL is required for proper expression in leaves

Adult pkl plants are dark green late-flowering semi-dwarfs that exhibit many other shoot phenotypes that are consistent with a defect in GA signal transduction (Ogas et al., 1997). Although previous analyses had indicated that organs generated post-embryonically in pkl plants do not express embryonic traits, we wished to determine whether or not the genes that exhibited PKL-dependent expression during germination might also require PKL for proper regulation of expression in leaf tissue. If the transcript level of a gene was found to be elevated in pkl leaves, the gene might play a role in generation of the adult shoot phenotype.

Three of the genes that exhibit PKL-dependent repression during germination are also overexpressed in pkl leaves. qRT-PCR was performed using total RNA isolated from wild-type leaves and pkl leaves with gene-specific primers for the gene of interest (Figure 6). Transcripts for FUS3, GASA1, and Unknown1 were significantly (p < 0.05) higher in pkl leaves whereas transcript levels for the remaining genes were not PKL-dependent in leaves. The LEC1 transcript was not detected in either pkl or wild-type leaves. The implication of this analysis is that inappropriate expression of FUS3, GASA1, and Unknown1 contributes to the adult shoot phenotypes observed in pkl plants (see Discussion). In addition, analysis of gene expression in pkl leaves, as in pickle roots, reveals that PKL is only required at specific points in development for proper expression of many target genes.

Figure 6.

The FUS3 transcript is elevated in pkl leaves. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the relative transcript level of the genes of interest in wild-type leaves and pkl leaves. The transcripts examined represent genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression during germination. Genes are ordered by relative expression in pkl leaf tissue from highest to lowest from left to right. The LEC1 transcript was not detected in either tissue and is therefore not included on the graph. 18s rRNA was used as a standardization control, and expression levels are normalized to wild-type leaves. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

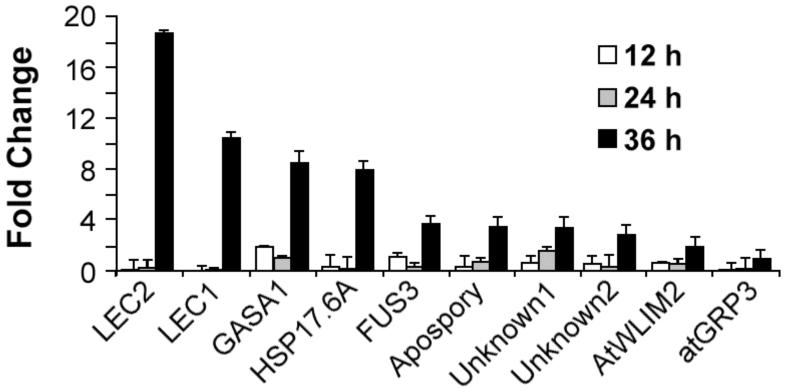

Derepression of transcript levels in pkl occurs during germination

We have proposed that LEC1 is directly repressed by PKL because of a correlation in the timing of two distinct events related to expression of embryonic identity in pkl seedlings. The transcript level of LEC1 is elevated in pkl seeds during that time at which GA is necessary to repress expression of embryonic identity in pkl seeds, between 24 and 36 hours after imbibition (Ogas et al., 1997; Ogas et al., 1999). If the transcripts of the nine other genes that exhibit PKL-dependent repression were elevated in germinating pkl seeds with the same timing as the LEC1 transcript, this result would suggest that these genes are also direct targets of PKL. For the subsequent analysis, it is important to note that we used seeds that were 100% germinated by 36 hours and that represent the same seed batch for which the timing of GA action was determined (Ogas et al., 1997) and in which the LEC1 transcript was derepressed between 24 and 36 hours after imbibition (Ogas et al., 1999). The seeds used to derive the data in Figures 1-3 germinate at a slower rate (100% germination at 48 hours) and so various time points should not be compared in these experiments, only the relative state of germination.

We found that transcripts of all nine genes were elevated in germinating pkl seeds in a manner similar to that of LEC1. qRT-PCR was performed using the total RNA isolated from wild-type and pkl seeds pre-imbibition and 12, 24, and 36 hours after imbibition (Figure 7). All of the genes tested showed an increase in the relative expression in pkl seeds between 24 and 36 hours after imbibition. Thus the transcript level of these genes is coordinately derepressed during the time in which the fate of the primary root in pkl seedlings is determined. This observation is consistent with the hypotheses that inappropriate expression of these genes contributes to the observed inability of pkl seedlings to repress embryonic identity and that some or all of these genes are directly regulated by PKL.

Figure 7.

Genes exhibit coordinate regulation by PKL during germination. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the relative transcript level of the genes of interest in wild-type seeds and pkl seeds that were desiccated or imbibed for 12, 24, and 36 hours. The transcripts examined represent genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression during germination. Genes are ordered by relative expression in pkl seeds at 36 hours after imbibition from highest to lowest from left to right. 18s rRNA was used as a standardization control, and expression levels are normalized to wild-type seeds at each time point. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

DISCUSSION

PKL codes for a putative CHD3 chromatin-remodeling factor (Eshed et al., 1999; Ogas et al., 1999) that is required for repression of embryonic identity in seedlings and for repression of LEC1 expression during germination (Ogas et al., 1997; Ogas et al., 1999). Ongoing work in animal systems indicates that CHD3 proteins function as negative regulators of transcription that are recruited to specific promoters. It was recently found that a CHD3 protein plays a role in development of C. elegans that is strikingly similar to that of PKL in Arabidopsis; worm embryos in which expression of LET-418 (a CHD3 gene) has been decreased by RNAi are defective in repression of germline fate in somatic cells (Unhavaithaya et al., 2002). Characterization of the role of PKL enables us to explore the role of a CHD3 protein in regulation of gene expression in plants in the context of an analogous developmental function (repression of embryonic identity).

Identification of additional genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression

Wild-type levels of GA are necessary between 24 and 36 hours after seed imbibition to repress expression of embryonic identity in pkl primary roots (the “pickle root” phenotype). Similarly, the LEC1 transcript is first elevated in germinating pkl seedlings between 24 and 36 hours after imbibition. The implication of these two observations is that PKL and GA are acting during this time to determine the ability of pkl seedlings to express embryonic identity later in development. Thus we chose to screen for genes that exhibited PKL-dependent transcript levels during this stage of development to give us the greatest chance to identify i) genes whose inappropriate expression contribute to derepression of embryonic identity and ii) genes that are directly regulated by PKL.

A candidate gene approach was undertaken to examine the role of PKL in regulation of expression of other genes previously implicated in embryogenesis (Figure 1). Of the six genes examined, only the LEC2 transcript behaved similarly to the LEC1 transcript and was strongly elevated in germinating pkl seed. In contrast, expression of the seed-specific maturation regulatory factor ABI3 (Giraudat et al., 1992) was not significantly altered under any condition examined. Thus these data reveal that PKL is not universally required for repression of all regulatory genes involved in seed formation at this point in development.

The microarray data provided evidence that 293 genes (3.5% of the genes queried) may exhibit PKL-dependent expression before germination is complete. These genes do not tend to occur in tandem arrays on a chromosome, an observation that supports the hypothesis that PKL acts in a locus-specific manner. To our knowledge, these data represent the first attempt to characterize the effect of a mutant CHD3-encoding gene on global transcript levels in the context of a developmental transition. In this light, it is intriguing to note that the representation of genes that code for predicted heat shock proteins is increased among the genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression in comparison to their representation among all of the genes on the arrays. The expression of heat shock proteins is induced during seed maturation (Wehmeyer et al., 2000). Similarly, we found that 12 of the 56 genes identified by microarray analysis as having transcript levels increased by two-fold or more in pkl seeds may be associated with some aspect of embryo or seed development, an observation consistent with the established role of PKL in repression of embryonic differentiation traits (See http://www.biochem.purdue.edu/research/ogas_lab/arrays/ Supplementary Table 1a). These data are also consistent with observations made by others regarding the role of CHD3 proteins in repressing alternative differentiation states in animal systems (Kehle et al., 1998; Solari et al., 2000; Unhavaithaya et al., 2002; von Zelewsky et al., 2000)

We have also identified 69 genes that exhibit uniconazole-P dependent expression that is not dependent on the state of the PKL locus as well as 88 genes that are expressed at different levels in pkl seeds germinated in the presence of uniconazole-P. (See http://www.biochem.purdue.edu/research/ogas_lab/arrays/ for a complete list of these genes.) Our observations regarding analysis of these genes will be described elsewhere.

We chose to focus our subsequent analysis on genes that exhibit robust PKL-dependent expression analogous to that of LEC1 and LEC2. By analogy to the known roles of LEC1 and LEC2 in embryogenesis (Lotan et al., 1998; Stone et al., 2001), we felt that genes exhibiting similar PKL-dependent regulation were likely to contribute substantively to the derepression of embryonic identity in pkl seedlings. Of the 293 genes that we identified as exhibiting PKL-dependent expression by microarray analysis, transcript levels for 56 were elevated by at least two-fold in pkl seeds. We selected 12 genes for verification of PKL-dependent expression by qRT-PCR and observed that expression of 8 of the 12 genes was elevated in pkl seedlings. These results indicated that our approach worked well. It should be noted, however, that the final determination of whether or not our 66% success rate is a reliable predictor of future success would be dependent on repeated trials and/or computer simulation studies. Transcript levels of 7 of the genes were elevated four-fold or more in germinating pkl seed. These genes thus exhibited PKL-dependent expression that was comparable to that of LEC1 and LEC2 when assayed by qRT-PCR (Figure 1) and were therefore selected for follow-up analysis.

Identification of a potential transcriptional regulator of embryogenesis

We examined whether or not the seven genes that had transcript levels that were elevated four-fold or more in pkl seed were preferentially expressed in developing siliques. We carried out this analysis in part to address the hypothesis that one or more of the genes might have a seed-specific pattern of expression analogous to the LEC genes. We observed that AtWLIM2 was preferentially expressed in developing siliques in a manner analogous to the LEC gene FUS3 (Figure 4).

It should be noted that our expression analysis of whole siliques was designed only to identify genes whose transcripts were strongly elevated in developing seeds similarly to the LEC genes. Such an analysis would not identify genes for which the corresponding transcript level was more modestly elevated in embryos, or those genes for which the corresponding transcript was elevated at a different point in development. In fact, the HSP 17.6A transcript has been shown to be elevated in maturing seeds (Sun et al., 2001). In addition, it is intriguing to note that two of the seven genes are related to genes whose expression is elevated during somatic embryogenesis; elevated expression of glycine-rich proteins such as GRP3 is associated with somatic embryogenesis (Magioli et al., 2001; Sato et al., 1995) and the apospory-related gene has sequence similarity to a gene whose expression is elevated during apomixis in buffelgrass (Gustine et al., 1993).

In an attempt to explore the possibility that expression of genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression during germination is correlated with embryogenesis, we examined the transcript levels for all 56 genes that we identified as exhibiting 2× or greater dependence on PKL in a previously generated microarray dataset of developing seeds (Girke et al., 2000). This analysis was not very informative; only 3 of 56 genes were represented in the developing seed microarray dataset. None of the 3 genes were represented in the 12 genes that we examined by qRT-PCR. Transcript levels for these three genes were not elevated in developing embryos and did not change during embryogenesis (Girke et al., 2000; Ruuska et al., 2002) (See http://www.biochem.purdue.edu/research/ogas_lab/arrays/ Supplementary Table 1a).

If expression of one or more genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression during germination were not elevated at some point during seed development, this observation would not rule out the possibility that these genes may play a significant role during embryogenesis. In this regard, it is interesting to note that comparison of microarray data with phenotypic characterization of deletion mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in various growth conditions has revealed that relative expression of a gene in a particular context is not sufficient to serve as a robust predictor of the functional significance of the gene in that context (Giaever et al., 2002).

The observation that AtWLIM2 is expressed preferentially in developing siliques is intriguing. Transcription factors that contain LIM domains are important regulators of development in animal systems (Dawid et al., 1998). The AtWLIM2 protein has greater than 50% sequence identity to Ntlim2, which has been demonstrated to bind to DNA in a sequence-specific manner and to regulate transcription of genes involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in tobacco (Kawaoka et al., 2000). This level of sequence conservation in combination with the observed expression profile suggests that AtWLIM2 may be functioning as a transcriptional regulator in Arabidopsis embryo development in a manner analogous to LEC transcriptional regulators. In support of a potential role for AtWLIM2 in embryogenesis, we have observed that plants that are heterozygous for a T-DNA tagged allele of AtWLIM2 exhibit a segregating embryo-lethal phenotype but have yet to determine whether or not this phenotypic trait is linked to the mutant Atwlim2 allele (unpublished data).

PKL is a negative regulator of the LEAFY COTYLEDON genes

Analysis of transcript levels in pickle roots suggests that derepression of the LEC genes is likely to play a significant role in generation of the pickle root phenotype. Transcript levels for LEC1, LEC2, and FUS3 are elevated more than 100-fold in pickle roots in comparison to wild-type roots. Transgenic seedlings in which LEC1 or LEC2 are ectopically expressed continue to exhibit embryonic differentiation traits after germination (Lotan et al., 1998; Stone et al., 2001). Based on the combined observations that all three LEC genes are coordinately regulated by PKL during germination (Figure 7) and that expression of all three genes is greatly increased in pickle roots (Figure 5), we propose that PKL is acting as a master regulator that is required for repression of all three genes during germination. We furthermore propose that inappropriate expression of these three genes is likely to contribute substantively to the ability of pkl primary roots to continue to express embryonic differentiation traits after germination. Analysis of the expression pattern of the LEC genes in germinating pkl seeds through a GUS reporter or in situ RNA analysis might shed light on why embryonic identity is preferentially expressed in the primary roots of pkl seedlings. We are unaware of any other transcriptional regulator that has been shown to be necessary for proper expression of all three LEC genes.

Identification of a putative PKL-dependent regulon specifically associated with germination

Genes that exhibit PKL-dependent expression during germination do not necessarily exhibit a similar dependence on PKL at other times during plant development. Expression of five of 10 of the genes is not elevated in pickle root tissue (Figure 5). Thus although inappropriate expression of these genes may play a role in determining the potential to express the pickle root phenotype, inappropriate expression of these genes is not a necessary differentiation characteristic of the pickle root itself. In contrast, we observe that three genes exhibit PKL-dependent expression in leaves (Figure 6), suggesting that inappropriate expression of these genes may play some role in generation of the shoot phenotype. Derepression of embryonic identity has not been observed in pkl leaves. Instead, pkl shoots express phenotypes that are consistent with a defect in GA signal transduction (Ogas et al., 1997; Ogas et al., 1999). In this regard, further exploration of the role of PKL in repression of GASA1, a gene that is known to exhibit GA-dependent expression (Herzog et al., 1995), may shed light on the role of PKL in GA-dependent responses.

Despite the fact that these genes do not exhibit uniform PKL-dependent expression at other points in development, expression of these genes is remarkably similar during germination of pkl seeds. The transcripts of all eleven genes, not only the LEC genes, are elevated in pkl seeds between 24 and 36 hours after imbibition. It remains to be determined if the pkl-dependent derepression of all of these genes will continue to appear as uniform if the transcript levels are measured at more frequent intervals. Nonetheless, the implication of this observation is that these genes identify a PKL-dependent regulon that requires PKL for repression of transcription during germination but not necessarily at other points in development.

This result is particularly striking given that the genes were initially identified based solely on their relative transcript level in pkl seeds at a single point in germination. It seemed quite reasonable to anticipate that some transcripts might exhibit continuous elevation in the absence of PKL, rather than elevation at a particular stage of the germination process. Our hypothesis is that the transcript level of these genes is elevated specifically at this point in germination because PKL is necessary at this time to directly repress transcription of one or more of these genes. Consistent with such a proposed time of action, we have observed that the PKL transcript is expressed during imbibition (unpublished data) in addition to other stages of the life cycle (Ogas et al., 1997). Analysis of the sequence of the upstream regions of these PKL-dependent genes does lead to the identification of common sequence motifs (data not shown), but it is not yet known if any of these motifs are involved in conferring PKL-dependent regulation.

The data presented has not illuminated the role of GA in penetrance of the pickle root phenotype. We have shown that the transcript levels of a number of genes, some of which are known positive regulators of embryonic identity, are coordinately derepressed during germination in pkl seedlings. Our working model is that inappropriate expression of these genes contributes to the inability of pkl seedlings to repress embryonic identity and that one or more of these genes are directly repressed by PKL, a CHD3-chromatin remodeling factor. Strikingly, although inhibition of GA biosynthesis through the application of uniconazole-P greatly increases penetrance of the pickle root phenotype (Ogas et al., 1997), the presence of uniconazole-P either has no effect on or slightly decreases the transcript level of the PKL-dependent genes examined (Figure 3). Our interpretation of these observations is that the absence of PKL leads to the transcriptional derepression of a set of genes that have the potential to generate embryonic differentiation traits. In some seedlings, the inappropriate expression of this suite of genes leads to the establishment of the pickle root phenotype, in which the primary root terminally differentiates into an organ that expresses both root-like and embryo-like differentiation traits. Inhibition of GA biosynthesis during germination increases the probability that the transcriptional derepression of the PKL-dependent genes will lead to establishment of the pickle root phenotype by a mechanism that has yet to be identified. Further characterization of genes that are expressed at significantly different levels when pkl seeds are germinated in the presence of uniconazole-P may be informative in this regard (Figure 1, see http://www.biochem.purdue.edu/research/ogas_lab/arrays/).

In summary, we have identified a number of genes that exhibit PKL-dependent repression during germination. Limited characterization of these genes suggests that PKL is necessary for repression for some but not all regulators of embryogenesis. In particular, PKL is necessary for repression of the LEC genes. We anticipate that further characterization of the genes that we have identified will lead to the discovery of novel regulators of embryogenesis as well as to uncovering genes that are directly regulated by PKL.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Growth Conditions

Seeds or plants incubated on synthetic media (Ogas et al., 1997) were grown in a CU36L5 incubator (Percival Scientific) under 24h illumination. Plants in pots were grown in AR75L growth chambers (Percival Scientific) under 24h illumination. For expression analysis during germination by both qRT-PCR and microarray (Figures 1, 2, and 3), seeds were sown at a density of 100 mg of seeds (∼3000 seeds) per 150 mm diameter petri dish. The media was supplemented with 10-8 M uniconazole-P or solvent alone (0.01% methanol final concentration). Samples were collected when 50% of the seeds had cracked seed coats (approximately 32 h post imbibition). Alternatively, samples were collected at 0, 12, 24, and 36 h post imbibition (Figure 7). Root, leaf, and silique tissue was collected from 32-day old plants. Siliques in the early stages of development at which both heart stage and torpedo stage embryos could be observed (which consisted of the first 5 silique pairs after the siliques were greater than 1 cM in length) were collected for RNA extraction. For expression analysis of pickle root tissue and wild-type root tissue plants were grown on media containing 10-8 M uniconazole-P and for 4 d and then transferred to new plates containing 10-6 M cytokinin. Root tissue was collected after 3 wk on these plates.

RNA Isolation and RNA Hybridization

Total RNA was isolated as described previously (Verwoerd et al., 1989). All subsequent experimental manipulations were carried out as per manufacturers instructions. Total RNA was further purified with Qiagen RNeasy columns (catalog 74904). cDNA was generated from 10 μg of total RNA using the Superscript Choice System (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies). A T7-(dT)24 oligonucleotide was used for first strand synthesis. Double stranded cDNA was cleaned using phenol:chloroform extraction and Phase Lock Gel (Eppendorf-5 Prime). Biotin labeled cRNA was generated using the BioArray High Yield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit (ENZO), cleaned and fragmented. Affymetrix Gene Chips (Arabidopsis Genome Array, catalog #900292) were hybridized with labeled cRNA at 45°C for 16 hours in an Affymetrix GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640. Washing and staining of the chips was performed using the Affymetrix Gene Chip Fluidics Station 400. Arrays were scanned in an HP GeneArray Scanner and data was analyzed with the Affymetrix Microarray Suite v. 4.0 software.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA (6 μg) was treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) in a 10 μl reaction using the manufacturer’s protocol. DNase treated RNA (4 μg) was reverse transcribed using SuperScript II and 100 ng random hexamers. The cDNA (∼2μg) was diluted to ∼2.6 ng/μl prior to quantitative PCR. Primers were designed using Primer Express 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) as recommended by the manufacturer. Reaction volumes were scaled to 20 μl final volume and were comprised of 10 μl SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), 5 μl primer mix, and 5 μl (∼13 ng) template cDNA. All reactions were repeated in triplicate. 18S ribosomal RNA was used as a normalization control for the relative quantification of transcript levels. Oligonucleotide primer sequences and primer concentrations used as well as critical threshold values for the figures presented can be found at http://www.biochem.purdue.edu/research/ogas_lab/arrays/.

Statistical Analysis and Archiving of Array Data

See Note 1, supplemental material at http://www.biochem.purdue.edu/research/ogas_lab/arrays/ for a complete description of analyses performed. The complete array data set has been deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) of NCBI, accession number GPL244.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Rick Westerman, Jeff Gustin, Monica Alvarez, and Linda Quach for their assistance in sequence analysis. We thank Heather Hostetler and Clint Chapple for thoughtful discussions. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM059770-01A1 and 5R01GM59770-02). Microarray analyses were partly supported by a grant to HJE from the Indiana 21st Century Research and Development Fund and by the Indiana Genomics Initiative, partly supported by the Lilly Endowment, Inc. Additional support was obtained by a grant to JRS from the Indiana 21st Century Research and Development Fund. SDR. was supported by funds from BASF. This is journal paper number 16933 of the Purdue University Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- Ahringer J. NuRD and SIN3 histone deacetylase complexes in development. Trends Genet. 2000;16:351–356. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawid IB, Breen JJ, Toyama R. LIM domains: multiple roles as adapters and functional modifiers in protein interactions. Trends Genet. 1998;14:156–162. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira DE, Seurinck J, Inze D, Van Montagu M, Botterman J. Differential expression of five Arabidopsis genes encoding glycine-rich proteins. Plant Cell. 1990;2:427–436. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.5.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson A, Gass N, Mundel C, Baltz R, Krauter R, Evrard JL, Steinmetz A. Molecular and expression analysis of a LIM protein gene family from flowering plants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2000;264:257–267. doi: 10.1007/s004380000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshed Y, Baum SF, Bowman JL. Distinct mechanisms promote polarity establishment in carpels of Arabidopsis. Cell. 1999;99:199–209. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Veronneau S, Dow S, Lucau-Danila A, Anderson K, Andre B, et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudat J, Hauge BM, Valon C, Smalle J, Parcy F, Goodman HM. Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1251–1261. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girke T, Todd J, Ruuska S, White J, Benning C, Ohlrogge J. Microarray analysis of developing Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1570–1581. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustine DL, Sherwood RT, Hulce DA. A strategy for cloning apomixis-associated cDNA markers from buffelgrass. In: Baker MJ, Crush JR, Humphreys LR, editors. Proceedings of the XVII International Grassland Congress. Vol. 2. Dunmore Press; Palmerston North: 1993. pp. 1033–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Harada JJ. Role of Arabidopsis LEAFY COTYLEDON genes in seed development. J. Plant. Physiol. 2001;158:405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht V, Vielle-Calzada JP, Hartog MV, Schmidt ED, Boutilier K, Grossniklaus U, de Vries SC. The Arabidopsis SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE 1 gene is expressed in developing ovules and embryos and enhances embryogenic competence in culture. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:803–816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck GR, Perry SE, Nichols KW, Fernandez DE. AGL15, a MADS domain protein expressed in developing embryos. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1271–1282. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog M, A.-M. D, Grellet F. GASA, a gibberellin-regulated gene family from Arabidopsis thaliana related to the tomato GAST1 gene. Plant Mol. Bio. 1995;27:743–752. doi: 10.1007/BF00020227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi K, Kamiya Y, Sakurai A, Oshio H, Takahashi N. Studies of sites of action of a new plant growth retardant (E)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4,4-dimethyl-2-(1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)-1-penten-3-ol (S-3307) and comparative effects of its stereoisomers in a cell-free system from Cucurbita maxima. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985;26:821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaoka A, Kaothien P, Yoshida K, Endo S, Yamada K, Ebinuma H. Functional analysis of tobacco LIM protein Ntlim1 involved in lignin biosynthesis. Plant J. 2000;22:289–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle J, Beuchle D, Treuheit S, Christen B, Kennison JA, Bienz M, Muller J. dMi-2, a hunchback-interacting protein that functions in polycomb repression. Science. 1998;282:1897–1900. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith K, Kraml M, Dengler NG, McCourt P. fusca3: A Heterochronic Mutation Affecting Late Embryo Development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1994;6:589–600. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.5.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Bentsink L, Hilhorst H. Seed dormancy and germination. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(01)00219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotan T, Ohto M, Yee KM, West MA, Lo R, Kwong RW, Yamagishi K, Fischer RL, Goldberg RB, Harada JJ. Arabidopsis LEAFY COTYLEDON1 is sufficient to induce embryo development in vegetative cells. Cell. 1998;93:1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luerssen H, Kirik V, Herrmann P, Misera S. FUSCA3 encodes a protein with a conserved VP1/AB13-like B3 domain which is of functional importance for the regulation of seed maturation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;15:755–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magioli C, Barroco RM, Rocha CAB, de Santiago-Fernandes LD, Mansur E, Engler G, Margis-Pinheiro M, Sachetto-Martins G. Somatic embryo formation in Arabidopsis and eggplant is associated with expression of a glycine-rich protein gene (Atgrp-5) Plant Science. 2001;161:559–567. [Google Scholar]

- Meinke DW. A homeotic mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana with leafy cotyledons. Science. 1992;258:1647–1650. doi: 10.1126/science.258.5088.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinke DW, Franzmann LH, Nickle TC, Yeung EC. Leafy Cotyledon mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1049–1064. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.8.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murawsky CM, Brehm A, Badenhorst P, Lowe N, Becker PB, Travers AA. Tramtrack69 interacts with the dMi-2 subunit of the Drosophila NuRD chromatin remodelling complex. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:1089–1094. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogas J, Cheng J-C, Sung ZR, Somerville C. Cellular differentiation regulated by gibberellin in the Arabidopsis thaliana pickle mutant. Science. 1997;277:91–94. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogas J, Kaufmann S, Henderson J, Somerville C. PICKLE is a CHD3 chromatin-remodeling factor that regulates the transition from embryonic to vegetative development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:13839–13844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruuska SA, Girke T, Benning C, Ohlrogge JB. Contrapuntal networks of gene expression during Arabidopsis seed filling. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1191–1206. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Toya T, Kawahara R, Whittier RF, Fukuda H, Komamine A. Isolation of a carrot gene expressed specifically during early-stage somatic embryogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995;28:39–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00042036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solari F, Ahringer J. NURD-complex genes antagonise Ras-induced vulval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone SL, Kwong LW, Yee KM, Pelletier J, Lepiniec L, Fischer RL, Goldberg RB, Harada JJ. LEAFY COTYLEDON2 encodes a B3 domain transcription factor that induces embryo development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:11806–11811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201413498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Bernard C, van de Cotte B, Van Montagu M, Verbruggen N. At-HSP17.6A, encoding a small heat-shock protein in Arabidopsis, can enhance osmotolerance upon overexpression. Plant J. 2001;27:407–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong JK, Hassig CA, Schnitzler GR, Kingston RE, Schreiber SL. Chromatin deacetylation by an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelling complex. Nature. 1998;395:917–921. doi: 10.1038/27699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unhavaithaya Y, Shin TH, Miliaras N, Lee J, Oyama T, Mello CC. MEP-1 and a Homolog of the NURD Complex Component Mi-2 Act Together to Maintain Germline-Soma Distinctions in C. elegans. Cell. 2002;111:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwoerd TC, Dekker BM, Hoekema A. A small-scale procedure for the rapid isolation of plant RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2362. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.6.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zelewsky T, Palladino F, Brunschwig K, Tobler H, Hajnal A, Muller F. The C. elegans Mi-2 chromatin-remodelling proteins function in vulval cell fate determination. Development. 2000;127:5277–5284. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade PA, Jones PL, Vermaak D, Wolffe AP. A multiple subunit Mi-2 histone deacetylase from Xenopus laevis cofractionates with an associated Snf2 superfamily ATPase. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:843–846. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeyer N, Vierling E. The expression of small heat shock proteins in seeds responds to discrete developmental signals and suggests a general protective role in desiccation tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:1099–1108. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodage T, Basrai MA, Baxevanis AD, Hieter P, Collins FS. Characterization of the CHD family of proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11472–11477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Wong J, Moreno GT, Young MK, Cote J, Wang W. NURD, a novel complex with both ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling and histone deacetylase activities. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:851–861. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, LeRoy G, Seelig HP, Lane WS, Reinberg D. The dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen Mi2 is a component of a complex containing histone deacetylase and nucleosome remodeling activities. Cell. 1998;95:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo J, Niu QW, Frugis G, Chua NH. The WUSCHEL gene promotes vegetative-to-embryonic transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;30:349–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.