Abstract

Oncoprotein 18/stathmin (Op18) has been identified recently as a protein that destabilizes microtubules, but the mechanism of destabilization is currently controversial. Based on in vitro microtubule assembly assays, evidence has been presented supporting conflicting destabilization models of either tubulin sequestration or promotion of microtubule catastrophes. We found that Op18 can destabilize microtubules by both of these mechanisms and that these activities can be dissociated by changing pH. At pH 6.8, Op18 slowed microtubule elongation and increased catastrophes at both plus and minus ends, consistent with a tubulin-sequestering activity. In contrast, at pH 7.5, Op18 promoted microtubule catastrophes, particularly at plus ends, with little effect on elongation rates at either microtubule end. Dissociation of tubulin-sequestering and catastrophe-promoting activities of Op18 was further demonstrated by analysis of truncated Op18 derivatives. Lack of a C-terminal region of Op18 (aa 100–147) resulted in a truncated protein that lost sequestering activity at pH 6.8 but retained catastrophe-promoting activity. In contrast, lack of an N-terminal region of Op18 (aa 5–25) resulted in a truncated protein that still sequestered tubulin at pH 6.8 but was unable to promote catastrophes at pH 7.5. At pH 6.8, both the full length and the N-terminal–truncated Op18 bound tubulin, whereas truncation at the C-terminus resulted in a pronounced decrease in tubulin binding. Based on these results, and a previous study documenting a pH-dependent change in binding affinity between Op18 and tubulin, it is likely that tubulin sequestering observed at lower pH resulted from the relatively tight interaction between Op18 and tubulin and that this tight binding requires the C-terminus of Op18; however, under conditions in which Op18 binds weakly to tubulin (pH 7.5), Op18 stimulated catastrophes without altering tubulin subunit association or dissociation rates, and Op18 did not depolymerize microtubules capped with guanylyl (α, β)-methylene diphosphonate–tubulin subunits. We hypothesize that weak binding between Op18 and tubulin results in free Op18, which is available to interact with microtubule ends and thereby promote catastrophes by a mechanism that likely involves GTP hydrolysis.

INTRODUCTION

The dynamic turnover of microtubules is required for a number of cellular processes, including chromosome movement in mitosis (reviewed by Inoué and Salmon, 1995). In living cells the majority of microtubules exchange subunits with a soluble tubulin pool by a process of dynamic instability in which individual microtubules switch abruptly between states of elongation and rapid shortening. The switches between states are termed catastrophe (growth to shortening) and rescue (shortening to growth) and are thought to be regulated by the GTP or GDP composition of tubulin subunits at the microtubule ends (reviewed by Desai and Mitchison, 1997). Purified tubulin also undergoes the switching between growth and shortening characteristic of dynamic instability, but the dynamic turnover is slower in vitro, suggesting that associated proteins stimulate turnover in vivo (reviewed by Desai and Mitchison, 1997).

Using a functional assay to identify proteins that destabilize microtubules, Belmont and Mitchison (1996) purified a previously identified protein, oncoprotein 18/stathmin (Op181), also known as p19, metablastin, and prosolin (reviewed by Sobel, 1991; Belmont et al., 1996; Lawler, 1998). Subsequent studies have suggested that Op18 binds tubulin at a 1:2 M ratio (Curmi et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997). In addition, Op18 can prevent microtubule assembly or cause depolymerization of preassembled microtubules in vitro (Belmont and Mitchison, 1996; Curmi et al., 1997; Horowitz et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997). In cells, overexpression or microinjection of Op18 leads to loss of microtubule polymer (Marklund et al., 1996; Horowitz et al., 1997; Larsson et al., 1997). The ability of Op18 to destabilize microtubules is regulated by phosphorylation in vivo and in vitro (DiPaolo et al., 1996; Horowitz et al., 1997; Larsson et al., 1997; Melander Gradin et al., 1997, 1998). Taken together these studies suggest that Op18 functions to destabilize microtubules, but the mechanism responsible for this destabilization is currently controversial (Curmi et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997).

Two models have been proposed to account for Op18 destabilization of microtubules: 1) sequestration of tubulin dimers to prevent their assembly (Curmi et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997) or 2) stimulation of microtubule catastrophes at microtubule tips (Belmont and Mitchison, 1996). Differentiating between these models is difficult because proteins that sequester tubulin dimers should both slow the rate of microtubule elongation and increase the frequency of catastrophe because the latter is also sensitive to tubulin concentration (Walker et al., 1988). Thus a sequestering protein would increase catastrophes, but only to an extent consistent with the decreased free tubulin concentration (estimated from the decreased elongation rate). In contrast, a catastrophe promoter would increase microtubule catastrophes to an extent greater than that predicted by a decrease in available tubulin.

In the original study of Op18 activity in in vitro microtubule assembly assays, Belmont and Mitchison (1996) found that Op18 slowed elongation but also stimulated catastrophes threefold when compared with purified tubulin assembled at the same growth rate. This led them to conclude that Op18 is a microtubule catastrophe promoter. In contrast, Curmi et al. (1997) recently found that Op18 slows elongation but does not increase catastrophes. Based on these results and the ability of Op18 to bind tightly to tubulin (Curmi et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997), these groups have concluded that Op18 is a tubulin-sequestering protein and that the stimulation of microtubule catastrophes observed by Belmont and Mitchison (1996) resulted solely from this mechanism.

The major difference in the microtubule assembly assays used in these conflicting studies was the pH (6.8 vs. 7.5) and magnesium concentration (1 vs. 5 mM) of the PIPES buffer system used for microtubule assembly (Belmont and Mitchison, 1996; Curmi et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997). The pH difference may be critical because measurement of Op18 binding to tubulin showed a steep pH dependence in the range of pH 7. Tight binding was observed between pH 6.5 and 7.0, and weak binding was observed above pH 7.0 (Curmi et al., 1997). These studies led us to hypothesize that the composition of the buffer critically affects the activity of Op18 in vitro. To test this hypothesis we made direct observations of microtubule assembly under both sets of experimental conditions. We find that the activities of Op18 differ in different buffer systems, suggesting that the conflicting conclusions reported previously were each correct under the conditions used. We also expressed truncations of the Op18 protein that further support the dual functional activities of Op18. Because we could separate tubulin-sequestering and catastrophe-promoting activities of Op18 by changes in pH, we used these conditions to further probe Op18-mediated mechanisms responsible for catastrophe promotion independent of tubulin sequestration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA Constructs

DNA isolations and manipulations were performed using standard techniques. Op18, derived from a human cDNA, was expressed in Escherichia coli as the full-length protein or as the full-length protein tagged with an additional eight amino acid C-terminal FLAG epitope (Op18F) (Marklund et al., 1994) as described (Brattsand et al., 1993). Construction of the FLAG epitope-tagged C-terminal–truncated protein, with the sequence encoding amino acid 100–147 deleted (Op18F-Δ100–147), has been described previously (Marklund et al., 1994). For expression in E. coli, an NcoI to BamHI fragment was excised from pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and ligated into the corresponding sites of the pET3d expression vector. A FLAG epitope-tagged N-terminal–truncated protein, with the sequence encoding amino acids 5–25 deleted (Op18F-Δ5–25), was generated by a two-step procedure. First, pETH-3d was digested with NcoI and BamHI and ligated to double-stranded oligomers of the following two oligonucleotides: 5′-CATGGCGAGCTCCCGGGG-3′ and 5′-GATCCCCCGGGAGCTCGC-3′. The resulting plasmid, designated pETH-Op18-D5–149, encodes the first four amino acids of Op18 followed by a SacI site that was introduced without altering the encoded amino acid sequence. A PCR fragment covering the coding region corresponding to amino acids 26–149 was generated using Op18F as template together with primers 5′-TGCCGAGCTCACCTCGGTCAAAAGAATC-3′ and 5′-GCGGGATCCTTAGGAAGGGGATGGGG-3′. The PCR fragment was digested with SacI and BamHI and ligated to the corresponding sites of pETH-Op18-Δ5–149.

Protein Purification

Wild-type and truncated Op18 derivatives were expressed and purified as described previously, and protein concentrations were determined by amino acid composition (Brattsand et al., 1993).

Porcine brain tubulin and sea urchin axonemes were isolated as described by Vasquez et al. (1997). Additional bovine brain tubulin was purchased from Cytoskeleton (Boulder, CO). Op18 and tubulin were frozen in a buffer containing 100 mM Na+ PIPES, pH 6.8, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2 (our standard buffer in previous studies). Before use, axonemes were pelleted in an 80-fold excess of the appropriate assembly buffer (below) and resuspended in the same buffer.

Microtubule Assembly

The assembly of individual microtubules seeded from axoneme fragments was visualized using video-enhanced differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy as described previously (Vasquez et al., 1997). Briefly, axonemes were allowed to adhere to biologically clean coverslips, and the coverslips were then mounted on glass slides with strips of double-stick tape as spacers to create 50 μl chambers. Chambers were perfused with the appropriate assembly buffer to remove unbound axonemes. Tubulin samples with or without Op18 were then perfused into the chamber. These samples contained 7–13 μM tubulin, 1 mM GTP, and 0–2.7 μM Op18 after dilution into the different assembly buffers tested. The buffers used were Buffer A, (80 mM K+ PIPES, pH 6.8, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2), Buffer B, (80 mM K+ PIPES, pH 6.8, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2), Buffer C, (80 mM K+ PIPES, pH 7.5, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2), and Buffer D (80 mM K+ PIPES, pH 7.5, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2). The differences between these buffer solutions were pH (6.8 vs. 7.5) and MgCl2 concentration (1 mM vs. 5 mM). Slides were sealed and warmed to 35°C on the microscope stage, and individual microtubules were observed and recorded as described previously (Vasquez et al., 1997). Under these assembly conditions, microtubules assembled only from axonemes and the total amount of tubulin incorporated into microtubule polymer was insignificant compared with the total tubulin concentration.

For the data shown in Tables 1 and 2, each mean is the sum of two separate experiments in which each experiment recorded ∼40 min of microtubule assembly from a number of axonemes. Some of the data points in Figure 3 were derived from single experiments (∼40 min of microtubule assembly).

Table 1.

At pH 6.8, Op18 reduces microtubule elongation velocity and increases catastrophes at both microtubule ends

| 7 μM Tb | 9 μM Tb | 11 μM Tb | 11 μM Tb + | 11 μM Tb + | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 μM Op18 | 1.7 μM Op18 | ||||

| Plus ends | |||||

| Ve (μm/min) ± SD | 1.06 ± 0.27 | 1.41 ± 0.39 | 1.94 ± 0.32 | 1.57 ± 0.27 | 1.09 ± 0.28 |

| n | 37 | 29 | 50 | 16 | 39 |

| Time obs (min) | 76.9 | 68 | 91.2 | 27.9 | 70.7 |

| Vrs (μm/min) ± SD | 27.7 ± 7.0 | 30.7 ± 14.5 | 48.1 ± 22.8 | 35.1 ± 8.6 | 28.4 ± 8.5 |

| n | 24 | 15 | 18 | 10 | 25 |

| Time obs (min) | 6.4 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 4.3 |

| Kcat (s−1) ± SD | 0.0052 ± 0.001 | 0.0037 ± 0.0009 | 0.0033 ± 0.0008 | 0.0048 ± 0.002 | 0.0059 ± 0.001 |

| n | 24 | 15 | 18 | 8 | 25 |

| Kres (s−1) ± SD | 0.0026 ± ND | 0.015 ± 0.008 | 0.014 ± 0.007 | NO | 0.0039 ± ND |

| n | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Minus ends | |||||

| Ve (μm/min) ± SD | 0.40 ± 0.14 | 0.52 ± 0.19 | 0.73 ± 0.20 | 0.55 ± 0.20 | 0.47 ± 0.17 |

| n | 28 | 45 | 40 | 34 | 61 |

| Time obs (min) | 77.6 | 109.7 | 90 | 80.8 | 130.3 |

| Vrs (μm/min) ± SD | 30.0 ± 15.9 | 35.5 ± 17.8 | 34.5 ± 23.9 | 24.5 ± 18.9 | 37.3 ± 21.6 |

| n | 19 | 20 | 11 | 14 | 39 |

| Time obs (min) | 4.3 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 5.7 |

| Kcat (s−1) ± SD | 0.0041 ± 0.0009 | 0.003 ± 0.0007 | 0.002 ± 0.0006 | 0.0027 ± 0.0007 | 0.0049 ± 0.0008 |

| n | 19 | 20 | 11 | 13 | 38 |

| Kres (s−1) ± SD | 0.0078 ± 0.006 | 0.036 ± 0.01 | 0.032 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 0.015 ± 0.007 |

| n | 2 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 5 |

Parameters of dynamic instability measured in Buffer A as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Ve, Elongation rate; Vrs, shortening rate; Kcat, catastrophe frequency; Kres, rescue frequency; n, number of events; Time obs, total time observed; NO, not observed; ND, not determined.

Table 2.

Op18 promotes microtubule plus end catastrophes at pH 7.5

| 11 μM Tb | 11 μM Tb + 1.7 μM Op18 | 11 μM Tb + 2.7 μM Op18 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plus ends | |||

| Ve (μm/min) ± SD | 2.04 ± 0.34 | 1.97 ± 0.30 | 1.79 ± 0.61 |

| n | 61 | 64 | 22 |

| Time obs (min) | 141 | 116.6 | 19.8 |

| Vre (μm/min) ± SD | 62.4 ± 28.4 | 55.9 ± 23.9 | 41.4 ± 7.2 |

| n | 16 | 35 | 19 |

| Time obs (min) | 4.35 | 9.3 | 2.86 |

| Kcat (s−1) ± SD | 0.0019 ± 0.0005 | 0.0049 ± 0.0008 | 0.013 ± 0.003 |

| n | 16 | 34 | 16 |

| Range | 0.0011–0.0031 | 0.0034–0.0068 | 0.0074–0.021 |

| Kres (s−1) ± SD | 0.0077 ± 0.005 | 0.0018 ± ND | NO |

| n | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Minus ends | |||

| Ve (μm/min) ± SD | 0.66 ± 0.26 | 0.67 ± 0.27 | 0.71 ± 0.26 |

| n | 54 | 42 | 12 |

| Time obs (min) | 94.4 | 52.8 | 17 |

| Vre (μm/min) ± SD | 42.3 ± 31.3 | 33.2 ± 27.8 | 38.5 ± 14.7 |

| n | 36 | 28 | 7 |

| Time obs (min) | 5 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Kcat (s−1) ± SD | 0.0064 ± 0.001 | 0.0088 ± 0.002 | 0.0068 ± 0.003 |

| n | 36 | 28 | 7 |

| Range | 0.0045–0.0089 | 0.0059–0.013 | 0.0027–0.014 |

| Kres (s−1) ± SD | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.038 ± 0.01 | NO |

| n | 12 | 9 | 0 |

Parameters of dynamic instability measured in Buffer D as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Ve, Elongation rate; Vrs, shortening rate; Kcat, catastrophe frequency; Kres, rescue frequency; n, number of events; Time obs, total time observed; NO, not observed; ND, not determined; Range, lower and upper limits of the mean at 95% confidence calculated assuming a Poisson distribution of growth times (Johnson and Kotz, 1969).

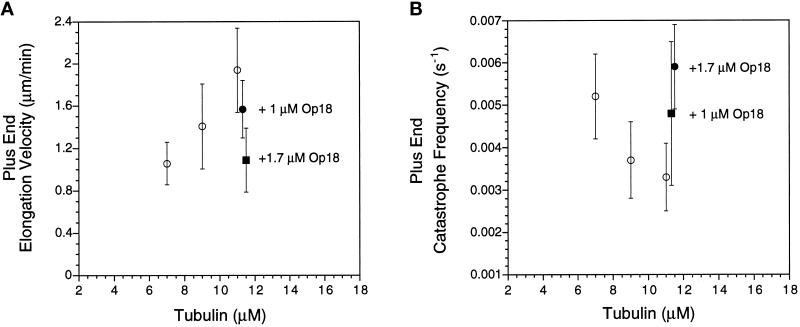

Figure 3.

Op18 at 1.7 μM increases microtubule plus end catastrophes over a range of tubulin concentrations in Buffer D. (A) Mean plus end catastrophe frequency ± SD is plotted as a function of tubulin concentration in the absence (open symbols) or presence of 1.7 μM Op18 (closed symbols). Op18 increased catastrophe frequency twofold (9 and 10 μM tubulin samples) to sixfold (12 μM tubulin). (B) Mean plus end elongation velocity ± SD. Symbols are the same as in A. Error bars are shown in only one direction for clarity. Regression lines through the data are shown, and these were used to calculate tubulin association and dissociation rate constants (Table 3).

Fixation

To examine the length and number of microtubules assembled from axonemes after 10 min, we used a fixation protocol described previously (Spittle and Cassimeris, 1996). Briefly, 5 μl of axonemes (in Buffer D) were allowed to adhere to a coverslip for 5 min. Next, a 50 μl solution was added to the coverslip and placed in a humid chamber at 37°C. For these experiments, 11 μM tubulin was assembled in Buffer D and 1 mM GTP containing 0, 1, 1.7, or 2.7 μM Op18. After 10 min, coverslips were fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde in the same buffer (37°C) for 1 min, rinsed in distilled water, and mounted onto slides. Slides were examined immediately by video-enhanced-DIC microscopy, and the length of microtubules was measured using a scaled ruler. Two coverslips were examined for each sample, and the lengths and numbers of microtubules were counted for 15–20 axonemes per coverslip. Plus ends were assigned based on the longer length of microtubules at this end of the axoneme.

Analysis of Tubulin Binding to Bead-bound Op18

Full-length Op18F, N-, or C-terminal Op18F truncations were bound to beads through the FLAG epitope tag on each protein. Agarose beads conjugated to the monoclonal antibody M2 (Kodak, Rochester, NY), which is specific for the FLAG epitope, were incubated with Op18F or truncations in Buffer B at 37°C for at least 1 h. The binding capacity of the M2 beads was ∼0.2–0.3 mg Op18F or truncations per milliliter of beads. The beads were then washed extensively in Buffer B and added to samples of bovine tubulin in Buffer B. To measure tubulin association with the beads, 20 μM tubulin was incubated with 7.5 μl of beads, and bound and unbound proteins were separated at the indicated time points as described below.

To allow rapid separation of tubulin bound to Op18F-coated beads, the bead suspension was applied into the cap of a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube in which the bottom of the tube contained 0.4 ml of 40% sucrose in Buffer B and a top layer of 0.2 ml of Buffer B. The cap was closed, keeping the bead suspension hanging in the cap, and the samples were centrifuged at the indicated time points (1 min, 21,000 × g). Sedimented beads were boiled in SDS-sample buffer, and eluted material was separated on a 10–20% gradient SDS-PAGE. Tubulin and Op18 content were quantitated by Coomassie Blue staining of protein bands followed by scanning using a Personal Densitometer (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Bovine brain tubulin and a standard recombinant Op18 preparation, in which the protein mass had been determined by amino acid analysis, were used as internal standards. The data are expressed as the tubulin/Op18 M ratio in the pellet. The errors between independent determinations were routinely <10%.

Guanylyl (α, β)-methylene diphosphonate (GMPCPP)–Tubulin

This nonhydrolyzable GTP analog was synthesized as described previously (Hyman et al., 1992) and was provided by generous gifts from Arshad Desai (Harvard University) and Michael Caplow (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill). Tubulin (24 μM), free of exogenous nucleotides (Hyman et al., 1991), was incubated with 1 mM GMPCPP for 20 min at 0°C just before use (Hyman et al., 1992). The preparation of nucleotide-free tubulin and all subsequent steps were performed in Buffer D.

Microtubules assembled with GMPCPP show similar growth velocities at plus and minus ends (Caplow et al., 1994), making it impossible to distinguish polarity based on growth rate. Therefore, we used perfusion chambers (20 μl chamber volume) to generate microtubules capped by GMPCPP–tubulin subunits. First, 10 μM GTP–tubulin was assembled from axonemes, and the rates of microtubule assembly were later used to assign polarity. The chamber was then perfused with five chamber volumes of 4 μM GMPCPP–tubulin supplemented with an additional 1 mM GMPCPP. After 30–60 sec, chambers were then perfused with five chamber volumes of Buffer D to remove unincorporated GMPCPP–tubulin subunits. Any microtubules that were not capped by GMPCPP–tubulin subunits would depolymerize during this step. Solutions of 2.7–15 μM Op18 or 2.7 μM Op18/5.4 μM GTP–tubulin were then perfused through the chamber (five chamber volumes), and microtubules were followed for an additional 1–5 min.

Analysis of Microtubule Assembly Dynamics

The rates of microtubule elongation and shortening were determined from video tapes using software written by Salmon and colleagues (Gliksman et al., 1992). Plus and minus ends of microtubules were assigned based on the faster elongation rate at plus ends. For most axonemes examined, several microtubules grew from each axoneme end, and therefore plus and minus ends were assigned based on multiple measurements for each axoneme.

Transition frequencies were calculated as described by Walker et al. (1988). For all microtubules of a given polarity, catastrophe frequency was calculated by dividing the total number of catastrophes by the total time spent in elongation. Rescue frequency was calculated in a similar manner. SDs for transition frequencies were determined from the catastrophe, or rescue frequency, divided by the square root of the number of transitions observed (Walker et al., 1988). This calculation assumes a Poisson distribution of growth or shortening times (Walker et al., 1988).

Statistical tests to compare elongation rates were performed at the 95% confidence level using analysis of variance provided by Microsoft Excel. Because calculations of catastrophe frequency provide only a mean and SD (described above), we compared means using a Student’s t test for two means with unequal variance (95% confidence level) (Pollard, 1977). The predicted range of the means at the 95% confidence limit was also calculated, assuming a Poisson distribution of growth times (Johnson and Kotz, 1969; Caplow and Shanks, 1995).

Association and dissociation rate constants during elongation were determined for microtubules assembled in Buffer D. During elongation, microtubule assembly at each end is described by the equation (Walker et al., 1988): elongation velocity = kon[tubulin] − koff.

Rate constants were determined from plots of elongation velocity versus tubulin concentration, where the association rate constant (kon) is proportional to the slope and the dissociation rate constant (koff) is proportional to the Y-intercept. Calculations were based on 1634 tubulin dimers per micrometers of microtubule polymer.

RESULTS

Op18 Slows Microtubule Growth Rate in a Conventional Assembly Buffer

The studies that concluded that Op18 sequesters tubulin dimers were conducted in a conventional in vitro microtubule assembly buffer (PIPES buffer at pH 6.8) (Curmi et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997). We examined the effects of Op18 on microtubule assembly in this buffer (Buffer A). As shown in Figure 1A (for plus ends) and Table 1 (for plus and minus ends), the addition of 1 μM or 1.7 μM Op18 to 11 μM tubulin slowed elongation velocity at both microtubule ends. For example, plus end elongation velocity for a solution of 11 μM tubulin and 1.7 μM Op18 was similar to that observed with 7 μM tubulin in the absence of Op18 (confirmed by statistical analysis; p < 0.05). Likewise, addition of 1 μM Op18 to 11 μM tubulin slowed elongation to a rate similar to that observed for 9 μM tubulin alone (confirmed by statistical analysis; p < 0.05).

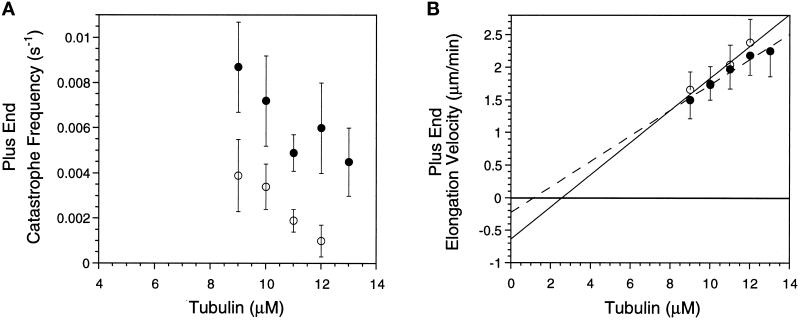

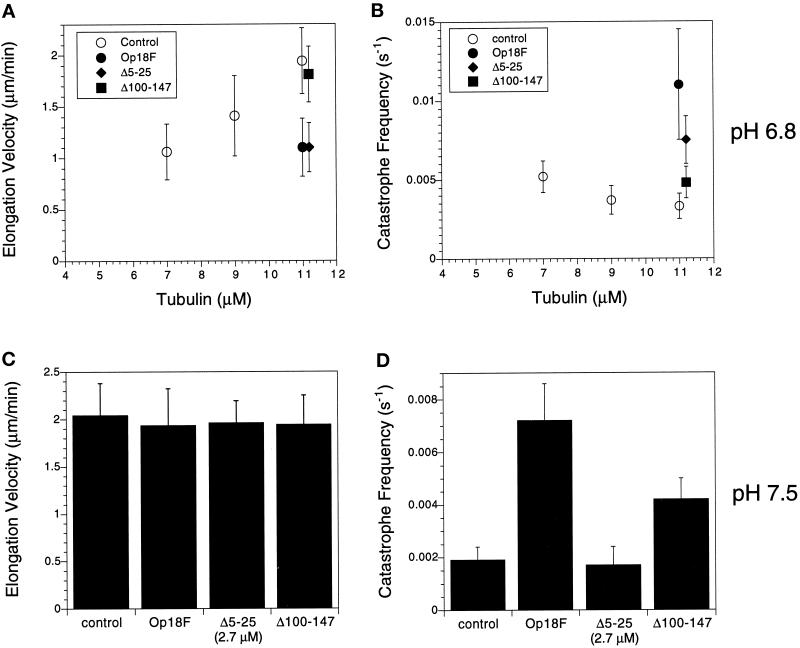

Figure 1.

Op18 decreases elongation velocity and increases catastrophe frequency at microtubule plus ends assembled in Buffer A. (A) Elongation velocity for microtubules assembled with purified tubulin (open symbols) or 11 μM tubulin plus Op18 (closed symbols, Op18 concentrations as noted). Data represent means ± SD. (B) Catastrophe frequency as a function of tubulin concentration for purified tubulin (open symbols) or 11 μM tubulin plus Op18 (closed symbols, Op18 concentrations as noted). Means ± SD were calculated as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. For clarity, the data for samples containing Op18 have been shifted along the x-axis to slightly higher tubulin concentrations.

Catastrophe frequency is sensitive to tubulin concentration where catastrophes become more frequent at lower tubulin concentrations (Walker et al., 1988) (Figure 1B and Table 1). Addition of Op18 to 11 μM tubulin also increased catastrophe frequency at both microtubule ends (Figure 1B and Table 1). For example, 1.7 μM Op18 increased catastrophes to a rate similar to that observed with 7 μM tubulin.

Increasing the MgCl2 concentration to 5 mM (Buffer B) did not change this pattern: Op18 both slowed microtubule elongation velocity and increased catastrophes at both microtubule ends (our unpublished results). Overall at pH 6.8, Op18 reduced microtubule assembly to an extent consistent with a sequestering mechanism, where 1 mol of Op18 sequesters 2 mol of tubulin dimers (see DISCUSSION).

Op18 Promotes Catastrophes at pH 7.5

We next examined microtubule assembly under the buffer conditions (Buffer D) originally used by Belmont and Mitchison (1996). Compared with more conventional microtubule assembly buffers, Buffer D has both a higher pH (7.5) and a higher concentration of MgCl2 (5 mM). When microtubules were assembled in this buffer in the absence of Op18, several changes in assembly dynamics were observed compared with assembly in Buffer A. In particular, microtubule plus ends shortened at a faster velocity in Buffer D. This was likely a consequence of the higher MgCl2 concentration (O’Brien et al., 1990) and was observed in samples containing 5 mM MgCl2 at both pH 6.8 and 7.5.

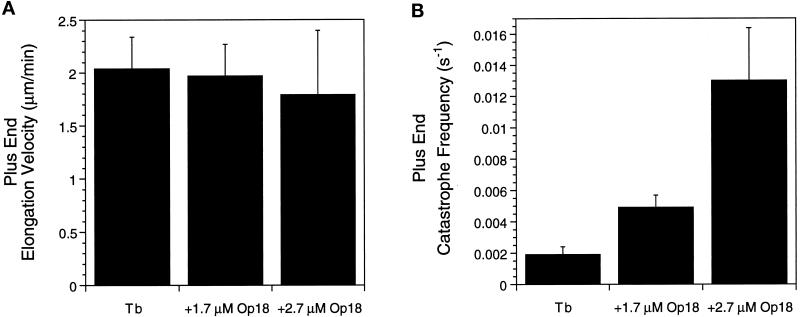

In contrast to the effects of Op18 on microtubule elongation rates measured in Buffers A or B, Op18 had little to no effect on microtubule elongation rates at either plus or minus ends when assayed in Buffer D (Figure 2A for plus ends, and Table 2 for plus and minus ends). For example, addition of 1.7 μM Op18 to 11 μM tubulin yielded a nearly identical plus end elongation velocity (2.04 ± 0.34 μm/min vs. 1.97 ± 0.30 μm/min). Increasing Op18 to 2.7 μM slightly decreased growth velocity to 1.8 μm/min. This mean velocity was statistically slower than the control rate (p < 0.05), but the ability of Op18 to slow elongation under these conditions was considerably less than the slowing observed at pH 6.8.

Figure 2.

Op18 promotes plus end catastrophes in Buffer D. (A) Histogram of microtubule elongation velocities for 11 μM tubulin (Tb) and 11 μM tubulin plus 1.7 or 2.7 μM Op18. At 2.7 μM, Op18 slightly slows plus end elongation velocity. (B) Histogram of average microtubule catastrophe frequency under the same conditions as A. Addition of 1.7 and 2.7 μM Op18 increased catastrophe frequency 2.5- and 7-fold, respectively. Data shown are means ± SD calculated as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS.

Although Op18 did not appreciably slow microtubule elongation rates in Buffer D, it did have a large effect on plus end catastrophes (Figure 2B and Table 2). The addition of 1.7 μM Op18 increased catastrophes 2.5-fold from one catastrophe, on average, every 526 sec for 11 μM tubulin to once every 204 sec after addition of 1.7 μM Op18. The differences in mean catastrophe frequency were statistically significant (p < 0.05), and the 95% confidence range for these means did not overlap (Table 2). A sevenfold increase in catastrophes was observed in solutions containing 2.7 μM Op18 (one catastrophe every 77 sec). In contrast, Op18 had little effect on minus end catastrophes (Table 2). A similar increase in plus end catastrophes was also observed with a second tubulin preparation (our unpublished results). Op18 also increased catastrophes for microtubules preassembled in the absence of Op18; perfusion with a solution of 2.7 μM Op18 and 11 μM tubulin resulted in a rapid increase in catastrophe frequency (our unpublished results).

Buffer D differs from conventional microtubule assembly buffers in both pH and MgCl2 concentration. To determine which factor, pH or MgCl2, is responsible for altering the activity of Op18, we examined microtubule assembly in Buffer C (pH 7.5), which contains a lower concentration of MgCl2 (1 mM). The addition of 1.7 μM Op18 to 11 μM tubulin did not slow microtubule elongation rates at either plus or minus ends under these conditions (for plus ends, 1.96 ± 0.31 μm/min vs. 1.95 ± 0.46 μm/min in the absence and presence of Op18, respectively). Similar to the results in Buffer D, Op18 increased plus end catastrophes fourfold under these conditions; in the absence of Op18, microtubules underwent catastrophes on average once every 752 sec compared with 1 catastrophe every 173 sec in the presence of Op18. Op18 also increased minus end catastrophes ∼1.3-fold under these conditions (our unpublished results). These results suggest that MgCl2 concentration does not modify the effects of Op18 on microtubule assembly.

We next extended analysis of microtubule assembly in Buffer D by adding 1.7 μM Op18 to tubulin over a range of tubulin concentrations from 9 to 13 μM. As shown in Figure 3A, Op18 increased plus end catastrophe frequency at each tubulin concentration tested with increased catastrophe frequencies ranging from two- to sixfold when compared with control samples at the same tubulin concentration. For all samples containing Op18, the increased catastrophe frequency did not show any time-dependent increase over the course of ∼40 min. Minus end catastrophes were similar to control values or increased twofold (our unpublished results). At each tubulin concentration examined there was little change in microtubule elongation velocity at either the plus or minus end (Figure 3B for plus ends; minus end, our unpublished results). These plots of elongation rate rate versus tubulin concentration were then used to calculate association and dissociation rate constants for tubulin subunits during elongation. Because elongation velocities were similar to those observed with tubulin alone, it is not surprising that Op18 had only small effects on the association and dissociation rate constants (Table 3). Op18 also slightly reduced the X-intercept, the critical concentration for elongation (Figure 3B).

Table 3.

Rate constants for tubulin association and dissociation during elongation

| Tubulin | Tubulin + 1.7 μM Op18 | |

|---|---|---|

| Slope (μm · μM−1 · min−1) | 0.25 | 0.20 |

| kon (μM−1 s−1) | 6.70 | 5.30 |

| Y-intercept (μm/min) | −0.63 | −0.22 |

| koff (s−1) | −17.10 | −6.00 |

Slopes and Y-intercepts were derived from regression analysis of data shown in Figure 3B. Association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants were calculated based on 1634 dimers/μm.

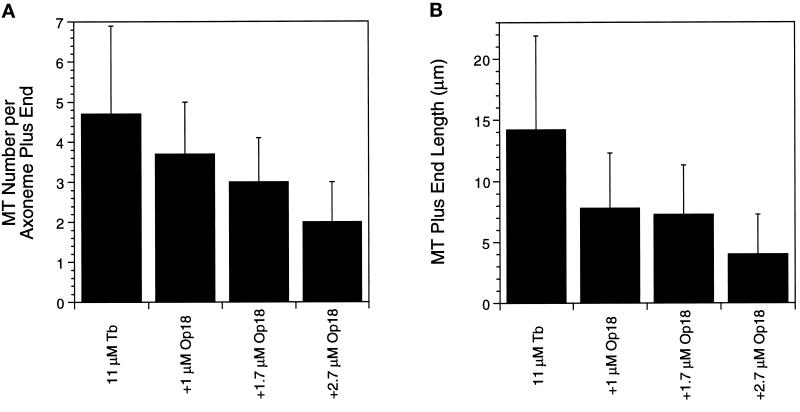

For each tubulin concentration examined, we noted that fewer microtubules were nucleated from axoneme ends in the presence of Op18. This decrease was next measured for microtubules assembled from axonemes for 10 min and then fixed. The results for the plus ends are shown in Figure 4. Op18 decreased the number of microtubules in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A). The decreased number of microtubules in samples containing Op18 is likely a consequence of the higher catastrophe frequency, but because we have not measured the rates of microtubule “nucleation” from the axoneme ends, we cannot determine whether the decreased number of microtubules is predicted from the kinetic data shown in Table 2. Addition of increasing concentrations of Op18 also resulted in decreased microtubule lengths (Figure 4B). The decreased lengths measured after 10 min of assembly fit well with lengths predicted by the real-time analysis. For example, 11 μM tubulin elongates for ∼8.8 min before catastrophe, predicting a length of 17.9 μm, which is similar to the measured mean length of 14 μm. Likewise, addition of 1.7 μM Op18 predicts an average microtubule lifetime of 3.4 min resulting in an average length of 7 μm, which fits well with the measured mean length of 7.3 μm.

Figure 4.

Op18 decreases the length and number of microtubules nucleated from axonemes. Solutions of 11 μM tubulin in the absence and presence of Op18 were allowed to assemble in Buffer D from axoneme fragments previously bound to coverslips. Coverslips were fixed after 10 min at 37°C and examined immediately by DIC microscopy. (A) Mean number of microtubules per axoneme plus end. (B) Mean length of plus end microtubules.

Truncated Op18 Proteins Reveal Separate Tubulin-sequestering and Microtubule Catastrophe-promoting Activities

The above results suggested that Op18 had both tubulin-sequestering activity (pH 6.8) and microtubule catastrophe-promoting activity (pH 7.5). It is possible that separate regions within Op18 are responsible for these different functional activities. We tested this hypothesis by expressing Op18 truncations that contained deletions in either the N-terminus (Op18F-Δ5–25) or the C-terminus (Op18F-Δ100–147) of the protein. Each of the truncated proteins was then examined in microtubule assembly assays. Because the truncated proteins contained a C-terminal eight amino acid FLAG epitope tag, we also examined the effect of the FLAG-tagged full-length protein (Op18F). At pH 6.8 (Buffer A), addition of 1.7 μM Op18F or Op18F-Δ5–25 to 11 μM tubulin slowed the microtubule elongation rate to an extent nearly identical to that observed with wild-type Op18 (plus ends shown in Figure 5A, our unpublished results for minus ends). Op18F and Op18F-Δ5–25 also stimulated catastrophes under these conditions (Figure 5B). Op18F-Δ5–25 stimulated catastrophes to an extent similar to that observed with wild-type Op18. Note that catastrophes were more frequent in samples containing Op18F compared with that observed with wild-type Op18 or Op18F-Δ5–25; the mechanism responsible for the increased activity of the full-length FLAG-tagged protein is not known.

Figure 5.

Deletions of the N or C terminus of Op18 result in loss of catastrophing promotion or tubulin sequestration, respectively. (A and B) Microtubule plus end elongation rate (A) and catastrophe frequency (B) at pH 6.8 for samples containing 11 μM tubulin and 1.7 μM Op18F or truncated proteins. For comparison, values for tubulin assembled at 7, 9, and 11 μM are shown (open symbols). The data for samples containing Op18F or truncated proteins are offset along the x-axis for clarity. (A) The full-length, epitope-tagged Op18F (closed circles) and the N-terminal truncation (Δ5–25; closed diamonds) slow microtubule elongation, whereas the C-terminal truncation (Δ100–147; closed squares) does not. As shown in B, each of these proteins stimulates catastrophes at pH 6.8. Catastrophe stimulation by the C-terminal truncation (Δ100–147; closed squares) is lower than that by the other proteins but is still 1–5-fold greater than tubulin alone. (C and D) Microtubule plus end elongation rates (C) and catastrophe frequency (D) at pH 7.5. All samples contained 11 μM tubulin. Op18F or Op18F-Δ100–147 was added at 1.7 μM, whereas the N-terminal truncation (Op18F-Δ5–25) was added at a higher concentration, 2.7 μM. As shown in C, Op18F and the truncated proteins did not slow microtubule elongation rate, consistent with the results shown in Figure 2 for wild-type Op18. (D) Both Op18F and the C-terminal truncated protein (Δ100–147) stimulate plus end catastrophes. In contrast, the N-terminal truncated protein (Δ5–25) was inactive, even at a higher concentration.

Truncation of a C-terminal region drastically reduced the activity of Op18 at pH 6.8. Addition of 1.7 μM Op18F-Δ100–147 had little to no effect on microtubule elongation rate at either plus (Figure 5A) or minus ends (our unpublished results). Interestingly, this C-terminal truncation was still able to increase catastrophes 1.5-fold at this pH (Figure 5B). Plus end catastrophes were observed once every 303 s for samples containing tubulin alone, and once every 208 s in samples containing 1.7 μM Op18F-Δ100–147. Addition of a higher concentration (2.7 μM) of the C-terminal–truncated protein further stimulated catastrophes to once every 108 s, although only slightly decreasing elongation rates; plus end elongation rate was 1.59 μM Op18F-Δ100–147 compared with 1.94 μm/min ± 0.32 for 11 μM tubulin alone.

We next examined microtubule assembly with the truncated proteins in Buffer D (pH 7.5). Consistent with the results obtained with wild-type protein, Op18F and the truncated proteins did not slow microtubule elongation at this pH (Figure 5C). Each of the truncated proteins was then examined for catastrophe-promoting activity. As shown in Figure 5D for plus ends, addition of 1.7 μM Op18F to 11 μM tubulin increased plus end catastrophes approximately fourfold (kcat = 0.0072 s−1) compared with tubulin alone (kcat = 0.0019 s−1). This FLAG epitope-tagged derivative showed slightly greater catastrophe-promoting activity compared with wild-type Op18 (∼2.5-fold catastrophe promotion; shown above). As shown in Figure 5D, the N-terminal–truncated protein Op18F-Δ5–25 did not promote catastrophes, even at a concentration of 2.7 μM (Figure 5D). In contrast, addition of 1.7 μM of the C-terminal–truncated protein (Op18F-Δ100–147) to 11 μM tubulin stimulated plus end catastrophes 2.2-fold. This stimulation is similar in magnitude to that observed with wild-type Op18 and slightly less than that observed with Op18F.

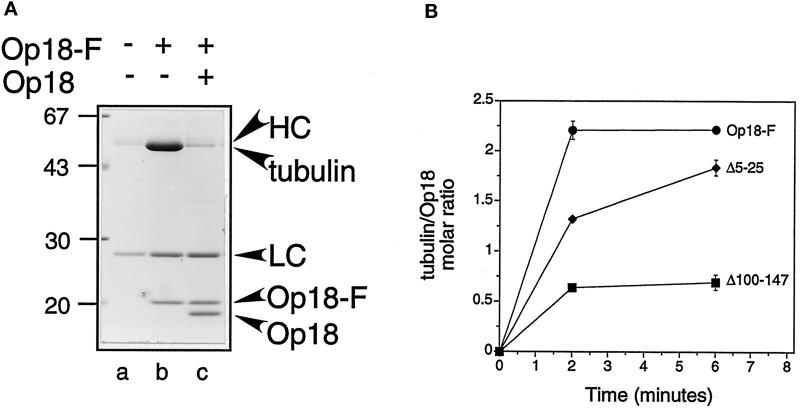

Tubulin Binds Poorly to Op18F-Δ100–147

Previous studies by Curmi et al. (1997) demonstrated that Op18 binding to tubulin is pH dependent; Op18 binds tightly to tubulin at pH <7.0, but it binds only weakly to tubulin at pH >7.0. In addition, both Curmi et al. (1997) and Jourdain et al. (1997) determined that each mol of Op18 binds 2 mol of tubulin in a stable complex (a “T2S complex”) that could be isolated by gel filtration or sedimentation at pH 6.8. These binding measurements, combined with the pH-dependent sequestering activity measured above (Figures 1 and 2), suggested that the ability of Op18 to sequester tubulin required formation of the T2S complex. Because the C-terminal truncation (Op18F-Δ100–147) does not slow the microtubule elongation rate at pH 6.8 (i.e., it does not sequester tubulin; Figure 5A), we hypothesized that this protein would not form a T2S complex at pH 6.8. To test this hypothesis, we examined the ability of tubulin to bind to Op18F or truncated proteins using an assay designed to allow the rapid separation of tubulin/Op18 complexes from soluble tubulin. For this assay, FLAG epitope-tagged proteins were first bound to agarose beads coupled to the M2 monoclonal antibody specific for the FLAG epitope (M2 beads). It is important to note that protein truncations bound to the beads at levels indistinguishable from the full-length Op18 (our unpublished results). These beads were incubated with tubulin and then rapidly pelleted through a sucrose cushion; tubulin bound to the beads was detected in the pellet (Figure 6A). Tubulin did not bind to M2 beads alone, and addition of excess, soluble Op18 (75 μM) was sufficient to displace tubulin from the Op18F/M2 beads (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Tubulin binding of Op18F and truncated derivatives. (A) Binding of tubulin (20 μM, 15 min at 37°C) to M2-coupled beads alone (lane a) or M2-coupled beads coated with Op18F (lanes b and c). Lane c shows that tubulin binding to Op18F-coated beads is blocked by addition of excess soluble Op18 (75 μM). Bead-bound material was separated by a rapid one-step procedure involving centrifugation through a sucrose gradient. Sedimented material was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by detection of proteins by Coomassie Blue staining. The position of of the heavy (HC) and light (LC) chains derived from the M2 antibody, as well as tubulin, Op18F, and the competitor Op18, are indicated. (B) Tubulin (20 μM) was added to Op18F coupled to M2 beads, and bead-bound tubulin was quantitated after incubation at 37°C for the indicated times. The molar ratio of tubulin associated with Op18 was determined as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS, and the contribution of nonspecific binding (∼8%) was subtracted from the presented data. The data points show the mean of duplicate samples, and the error bars reflect the range of duplicate samples. For most data points the error bars are smaller than the symbols. Data are representative of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

As shown in Figure 6B, 20 μM tubulin bound rapidly to Op18F beads and reached maximal binding within 2 min. Maximal binding was approximately 2 mol of tubulin per mol of Op18F. This is similar to the stable T2S complex measured previously (Curmi et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997). Tubulin also bound to the N-terminal truncation (Op18F-Δ5–25), binding was slightly slower, but reached a similar maximum value after ∼6 min. In contrast, the C-terminal deletion (Op18F-Δ100–147) bound considerably less tubulin and reached a maximal binding of only ∼0.5 mol of tubulin per mol of Op18.

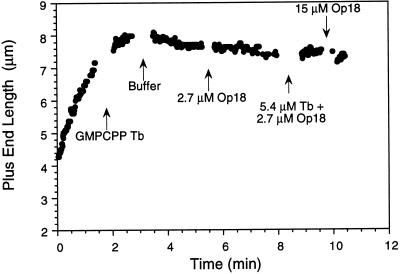

Op18 Does Not Destabilize GMPCPP-capped Microtubules

Because we were able to define conditions in vitro where Op18 acts as a plus end catastrophe promoter, we probed possible mechanisms responsible for this activity by examining whether Op18 could destabilize microtubules capped with the nonhydrolyzable GTP analogue GMPCPP. Microtubules capped with GMPCPP–tubulin subunits were stable for at least 20 min after dilution with Buffer D (our unpublished results), suggesting that these buffer conditions did not alter the very slow hydrolysis of GMPCPP in K+ buffers (Caplow et al., 1994). As opposed to XKCM1, a kinesin family member that can depolymerize GMPCPP microtubules (Desai et al., 1997), Op18 had no effect on GMPCPP-capped microtubules (Figure 7). Both microtubule plus and minus ends were stable in solutions containing 2.7–15 μM Op18 or 2.7 μM Op18 plus 5.4 μM tubulin (with or without GTP). Microtubule severing was never observed under any of these conditions.

Figure 7.

Op18 does not depolymerize GMPCPP-capped microtubules. Length versus time plot showing a plus end microtubule assembly initially at 10 μM tubulin in Buffer D. Sequential perfusions with the following solutions are marked: 4 μM GMPCPP-tubulin in Buffer D containing 1 mM GMPCPP; Buffer D alone; 2.7 μM Op18; 5.4 μM GTP-tubulin and 2.7 μM Op18; and finally 15 μM Op18. No catastrophes were observed after microtubules were capped with GMPCPP-tubulin. Similar results were obtained with 11 additional microtubule plus ends; some of these ends were followed for longer periods after the final perfusion with 15 μM Op18.

DISCUSSION

Studies of Op18 effects on microtubule assembly in vitro had led to conflicting ideas on how this protein destabilizes microtubules: either by promotion of catastrophes (Belmont and Mitchison, 1996) or by sequestering tubulin dimers (Curmi et al., 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997). These studies differed in the buffer composition used to study microtubule assembly. Our results show that both mechanisms are possible, but that the different mechanisms predominate under the different in vitro conditions. Thus, it is possible to separate a specific catastrophe-promoting activity from a tubulin-sequestering activity by small changes in pH.

Surprisingly, Op18 is not the only cytoskeletal-associated protein with activities demonstrated to be pH dependent. The small actin binding protein ADF/cofilin also shows pH-dependent actin filament-depolymerizing activity (Hawkins et al., 1993; Hayden et al., 1993). The actin filament-severing protein scinderin also appears to be partially regulated by pH (Rodriguez Del Castillo et al., 1992).

Op18 Sequesters Tubulin Dimers at pH 6.8

At pH 6.8 in a conventional microtubule assembly buffer (Buffer A), Op18 altered microtubule assembly in ways consistent with a tubulin-sequestering mechanism. Specifically, Op18 decreased microtubule elongation velocity in a dose-dependent manner. The addition of 1 μM Op18 to 11 μM tubulin resulted in elongation rates similar to that observed with 9 μM tubulin, whereas 1.7 μM Op18 further slowed elongation to near that observed with 7 μM tubulin. Decreased elongation rates were also measured at both plus and minus ends of microtubules; this is also consistent with a sequestering mechanism. Assuming that Op18 binds tubulin with high affinity under these conditions, the decreased growth rates are consistent with previous observations that each mol of Op18 binds 2 mol of tubulin heterodimers in Buffer A (Curmi et al. 1997; Jourdain et al., 1997). This 2:1 M complex between tubulin and Op18 was also measured in binding assays (discussed below).

Op18 also increased catastrophe frequency at both microtubule ends under these buffer conditions. The increased catastrophe frequencies observed with 1 and 1.7 μM Op18 added to 11 μM tubulin were similar to that observed with 9 and 7 μM tubulin, respectively. This suggests that the increased catastrophe frequencies are due to reduced free tubulin concentration and not to a specific promotion of catastrophe, consistent with conclusions reached by Jourdain et al. (1997) and Curmi et al. (1997).

At pH 7.5, Op18 Promotes Microtubule Catastrophes without Sequestering Tubulin Dimers

The pH of the buffer system alters the activity of Op18 (Tables 1 and 2). When the pH was raised from 6.8 to 7.5, Op18 had little effect on microtubule elongation velocity. This was observed at both microtubule ends. These observations suggest that Op18 does not sequester tubulin (or only weakly sequesters tubulin) under these buffer conditions. Although Op18 did not significantly slow microtubule assembly at pH 7.5, it did cause an increase in catastrophes, particularly at plus ends. Promotion of plus end catastrophes ranged from two- to sevenfold depending on tubulin or Op18 concentration (Figure 3 and Table 2). Increased catastrophes were observed in pH 7.5 buffers containing either 5 or 1 mM magnesium, suggesting that it is the pH of the buffer that modifies the activity of Op18. Minus ends were less sensitive to Op 18 and showed a ≤2-fold increase in catastrophes.

At pH 7.5, Op18 (1.7 μM) slightly reduced the critical concentration for elongation (Figure 3B). It is important to note that this is not a steady-state critical concentration (Walker et al., 1988). Rather, the steady-state critical concentration is a consequence of the four parameters of dynamic instability and can be estimated by the sum of the net gain and loss of tubulin subunits at the two microtubule ends per unit time (Walker et al., 1988). The microtubule assembly data in Buffer D suggests that the steady-state critical concentration is higher than 12–13 μM tubulin, so we were not able to calculate predicted steady-state critical concentrations in the presence and absence of Op18. Although we have not measured this directly, it is likely that Op18 increases a steady-state critical concentration. Microtubules assembled with Op18 at pH 7.5 undergo more frequent catastrophes (Table 2), and these microtubules are shorter on average (Figure 4). Thus at steady state, less tubulin would be present in polymer, and this would give rise to an increased steady-state critical concentration in the presence of Op18. Modeling studies are consistent with this idea; increasing catastrophe frequency threefold reduced the mean length of microtubules to 30% of their original length and reduced the percentage of microtubules in polymer from ∼63% to ∼18% (Gliksman et al., 1993). Therefore, sequestering proteins and catastrophe-promoting proteins could each increase a steady-state critical concentration, suggesting that this is not a useful way to differentiate between these two destabilizing mechanisms. Indeed, experiments with taxol-induced microtubule assembly show that Op18 decreases the amount of microtubule polymer at steady state, and this is unaffected by pH (N.L. and M.G., unpublished observations).

Deletions of Op18 N- or C-Terminus Separates Tubulin-sequestering and Catastrophe-promoting Activities

The two functional activities measured with full-length Op18 prompted us to examine whether separate protein regions within Op18 were responsible for tubulin sequestering and catastrophe promotion. Studies with Op18 containing deletions in the N- or C-terminus support this idea because these truncations showed distinctly different functional activities. Deletion of the N-terminus resulted in a protein that retained tubulin-sequestering activity (Figure 5A) but was unable to promote microtubule catastrophes (Figure 5D). In contrast, deletion of the C-terminal region resulted in loss of tubulin-sequestering activity without loss of catastrophe-promoting activity (Figure 5, A, B, and D). These results demonstrate that the N-terminus is necessary for catastrophe promotion, whereas the C-terminus is necessary for tubulin sequestration. It is not yet known whether additional regions also contribute to either tubulin sequestration or catastrophe promotion, or whether the regions we have identified are sufficient for these activities.

Tubulin Sequestration Requires Tight Binding between Op18 and Tubulin

Our binding studies demonstrated that full-length Op18F or the N-terminal deletion (Op18F-Δ5–25) bound tubulin well at pH 6.8. In contrast, Op18F-Δ100–147 bound tubulin poorly. This C-terminal–truncated protein also was incapable of sequestering tubulin because it did not slow microtubule elongation at pH 6.8. These results suggest that tight binding between Op18 and tubulin is necessary for sequestration. The results of Curmi et al. (1997) showing pH-dependent changes in Op18/tubulin complex formation are also consistent with the pH-dependent sequestering activity measured here with the full-length Op18, in which sequestering activity is detected under conditions that favor formation of a stable T2S complex.

How does Op18 Promote Catastrophes at pH 7.5?

The specific microtubule catastrophe-promoting activity of Op18 coincides with conditions in which Op18 binds weakly to tubulin: pH 7.5 (Figure 2) or deletion of the C-terminus (Figures 5 and 6). In this regard, it is interesting that the C-terminal deletion, which binds poorly to tubulin, is able to stimulate catastrophes at either pH 6.8 or 7.5. We hypothesize that weak binding between Op18 and tubulin results in free Op18 that could interact with microtubule ends to stimulate catastrophe. Under our in vitro assay conditions, the amount of microtubule polymer is negligible compared with tubulin dimers. When Op18 is bound tightly to tubulin (pH 6.8), the large tubulin pool may act as an Op18 “sink.” When the pH is raised to 7.5 or the C-terminus is deleted, we speculate that Op18 is released from tubulin, possibly allowing free Op18 to bind to microtubule ends and stimulate catastrophe.

The mechanism responsible for catastrophe promotion by Op18 is not yet clear, but Op18 likely promotes catastrophes by a mechanism distinct from XKCM1. This kinesin family member also promotes catastrophes and can depolymerize GMPCPP microtubules by an ATP-dependent mechanism (Desai et al., 1997). In contrast, we found that Op18 had no effect on microtubules capped with nonhydrolyzable GMPCPP–tubulin subunits (Figure 7). Our results suggest that Op18 promotes loss of a GTP cap at microtubule tips, but the mechanism cannot be differentiated by this study. Although GMPCPP–tubulin hydrolyzes nucleotide very slowly, it also shows very slow dissociation from microtubule ends (Hyman et al., 1992; Caplow and Shanks, 1996). Thus, Op18 could be acting on GTP–tubulin at microtubule ends to stimulate GTP hydrolysis or to promote GTP–tubulin dissociation. Therefore, we examined whether Op18 stimulates GTP–tubulin dissociation from microtubule plus ends. At 1.7 μM, Op18 slightly reduced the rate of GTP–tubulin dissociation (Table 3), suggesting that catastrophe promotion does not result from a stimulation of tubulin dissociation. Taken together, the results suggest that Op18 could promote catastrophes by stimulating GTP hydrolysis, but further studies are necessary to determine whether Op18 interacts directly with microtubule ends or whether Op18 stimulates GTP hydrolysis within the microtubule lattice.

Op18 Functions In Vivo

Several studies have documented that Op18 regulates microtubule polymer level in vivo. For example, overexpression or microinjection of Op18 resulted in microtubule polymer loss (Marklund et al., 1996; Horowitz et al., 1997; Larsson et al., 1997). Inhibition of Op18 activity, through phosphorylation (Melander Gradin et al., 1997, 1998), antibody injection (Howell, et al., 1997), or immunodepletion from Xenopus extracts (Belmont and Mitchison, 1996; Tournebize et al., 1997), resulted in increased microtubule polymer. Injection of antibodies to Op18 in living cells (Howell et al., 1997) or immunodepletion of Op18 from Xenopus extracts (Tournebize et al., 1997) also resulted in decreased microtubule catastrophes without a concomitant increase in microtubule elongation rate. Although these latter results are consistent with a catastrophe-promoting function for Op18, it is not yet known whether microtubule elongation rate is dependent on tubulin concentration in vivo, and this dependence is critical to differentiate between sequestering and catastrophe-promoting mechanisms. In this regard it is important to note that microtubule assembly is not sensitive to tubulin concentration in Xenopus egg extracts (Parsons and Salmon, 1997).

Although we cannot use changes in microtubule elongation rates to address how Op18 destabilizes microtubules in vivo, the truncated proteins examined in vitro suggest that Op18 has catastrophe-promoting activity in the cell. Op18 contains four serine residues within the N terminus (amino acid positions 16, 23, 38, and 63). Phosphorylation at Ser-16 is sufficient to significantly reduce Op18’s microtubule-destabilizing activity in vivo (Melander Gradin et al., 1997). This phosphorylation site is within the N terminus, a region necessary for catastrophe promotion in vitro. Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that phosphoryation turns off an activity associated with this region and supports the idea that Op18’s catastrophe-promoting region is active in vivo.

The tubulin-sequestering region of Op18 may also be active in vivo, but the fraction of tubulin sequestered would differ depending on the intracellular concentration of Op18. Op18 concentrations vary widely, and this protein is highly expressed in many leukemia cells (Brattsand et al., 1993). The high level of Op18 in leukemia cells could result in sequestration of a significant concentration of tubulin when compared with normal cells.

At this time it is not known whether pH regulates Op18 activity in vivo. Interestingly, several stimulatory signals result in changes in intracellular pH. Both fertilization (e.g., sea urchin eggs [Schatten et al., 1985]) and growth factor stimulation of quiescent cells (Bierman et al., 1988; Moolenaar et al., 1983) result in a more alkaline cytoplasm. This rise in intracellular pH may be sufficient to favor catastrophe promotion over tubulin sequestering, which could lead to changes in either microtubule polymer level or turnover.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Mike Caplow and Arshad Desai for gifts of GMPCPP. L.C. thanks the University of North Carolina–Duke motility journal club for helpful suggestions and Mike Caplow for a thought-provoking E-mail. Thanks also to Arshad Desai, Heather Deacon, Ted Salmon, and Rich Walker for critically reading early versions of this manuscript. B.H. and L.C. are supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health; N.L. and M.G. are supported by the Swedish Natural Research Council (B-AA/BU01744) and the Foundation for Medical Research at the University of Umeå.

Abbreviations used:

- GMPCPP

guanylyl (α, β)-methylene diphosphonate

- Op18

oncoprotein 18/stathmin

- Op18F

FLAG epitope-tagged Op18

- Op18F-Δ5–25

Op18F with amino acids 5–25 deleted

- Op18F-Δ100–147

Op18F with amino acids 100–147 deleted

REFERENCES

- Belmont L, Mitchison T. Identification of a protein that interacts with tubulin dimers and increases the catastrophe rates of microtubules. Cell. 1996;84:623–631. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont L, Mitchison T, Deacon HW. Catastrophic revelations about Op18/stathmin. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:197–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman AJ, Cragoe EJ, Jr, de Laat SW, Moolenaar WH. Bicarbonate determines cytoplasmic pH and suppresses mitogen-induced alakalinization in fibroblastic cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15253–15256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brattsand G, Roos G, Marklund U, Ueda H, Landberg G, Nanberg E, Sideras P, Gullberg M. Quantitative analysis of the expression and regulation of an activation-regulated phosphoprotein (oncoprotein 18) in normal and neoplastic cells. Leukemia. 1993;7:569–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplow M, Ruhlen RL, Shanks J. The free energy for hydrolyzis of a microtubule-bound nucleotide triphosphate is near zero: all of the free energy for hydrolyzis is stored in the microtubule lattice. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:779–788. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplow M, Shanks J. Induction of microtubule catastrophes by formation of tubulin-GDP and apotubulin subunits at microtubule ends. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15732–15741. doi: 10.1021/bi00048a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplow M, Shanks J. Evidence that a single monolayer tubulin-GTP cap is both necessary and sufficient to stabilize microtubules. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:663–675. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curmi PA, Andersen SSL, Lachkar S, Gavet O, Karsenti E, Knossow M, Sobel A. The stathmin/tubulin interaction in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25029–25036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1997;13:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Mitchison TJ, Walczak CE. Microtubule destabilization by XKCM1 and XKIF2—two internal motor domain subfamily kinesins. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:3a. (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- DiPaolo G, Pellier V, Catsicas M, Antonsson B, Catsicas S, Grenningloh G. The phosphoprotein stathmin is essential for nerve growth factor-stimulated differentation. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1383–1390. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliksman N, Parsons S, Salmon ED. Okadaic acid induces interphase to mitotic-like microtubule dynamic instability by inactivating rescue. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1271–1276. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliksman NR, Skibbens RV, Salmon ED. How the transition frequencies of microtubule dynamic instability (nucleation, catastrophe and rescue) regulate microtubule dynamics in interphase and mitosis: analysis using a Monte Carlo computer simulation. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1035–1050. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins M, Pope B, Maciver SK, Weeds AG. Human actin depolymerizing factor mediates a pH-sensitive destruction of actin filaments. Biochemistry. 1993;3:9985–9993. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden SM, Miller PS, Brauwieler A, Bamburg JR. Analysis of the interactions of actin depolymerizing factor with G-actin and F-actin. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9994–10004. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz SB, Shen H, He L, Dittmar P, Neef R, Chen J, Schubart UK. The microtubule-destabilizing activity of metablastin (p19) is controlled by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8129–8132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell BJ, Deacon H, Cassimeris L. Injection of antibodies against Op18 results in decreased microtubule catastrophes and increased microtubule polymer in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:165a. (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hyman A, Drechsel D, Kellogg D, Salser S, Sawin K, Steffen P, Wordeman L, Mitchison T. Preparation of modified tubulins. Methods Enzymol. 1991;196:478–485. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)96041-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman AA, Salser S, Drechsel DN, Unwin N, Mitchison TJ. Role of GTP hydrolyzis in microtubule dynamics: information from a slowly hydrolyzable analogue, GMPCPP. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1155–1167. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoué S, Salmon ED. Force generation by microtubule assembly/disassembly in mitosis and related movements. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1619–1640. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NL, Kotz S. Discrete Distributions. New York: Houghton Mifflin; 1969. pp. 96–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain L, Curmi P, Sobel A, Pantaloni D, Carlier M-F. Stathmin: a tubulin-sequestering protein which forms a ternary T2S complex with two tubulin molecules. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10817–10821. doi: 10.1021/bi971491b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson N, Marklund U, Melander Gradin H, Brattsand G, Gullberg M. Control of microtubule dynamics by oncoprotein 18: dissection of the regulatory role of multisite phosphorylation during mitosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5530–5539. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler S. Microtubule dynamics: if you need a shrink try stathmin/Op18. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R212–R214. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund U, Larsson N, Melander Gradin H, Brattsand G, Gullberg M. Oncoprotein 18 is a phosphorylation-responsive regulator of microtubule dynamics. EMBO J. 1996;15:5290–5298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund U, Osterman O, Melander H, Bergh A, Gullberg M. The phenotype of a “cdc2 kinase target site-deficient” mutant of Op18 reveals a role of this protein in cell cycle control. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30626–30635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melander Gradin H, Larsson N, Marklund U, Gullberg M. Regulation of microtubule dynamics by extracellular signals: cAMP-dependent protein kinase switches off the activity of oncoprotein 18 in intact cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:131–141. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melander Gradin H, Marklund U, Larsson N, Chatila TA, Gullberg M. Regulation of microtubule dynamics by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV/Gr-dependent phosphorylation of oncoprotein 18. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3459–3467. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar WH, Tsien RY, van der Saag PT, de Laat SW. Na+/H+ exchange and cytoplasmic pH in the action of growth factors in human fibroblasts. Nature. 1983;304:645–648. doi: 10.1038/304645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien ET, Salmon ED, Walker RA, Erickson HP. Effects of magnesium on the dynamic instability of individual microtubules. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6648–6656. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons SF, Salmon ED. Microtubule assembly in clarified Xenopus egg extracts. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1997;36:1–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)36:1<1::AID-CM1>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard J. A Handbook of Numerical and Statistical Techniques with Examples Mainly from the Life Sciences. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1977. pp. 161–163. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Del Castillo A, Vitale ML, Trifaro J-M. Ca and pH determine the interaction of chromaffin cell scinderin with phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and its cellular distribution during nicotinic-receptor stimulation and protein kinase C activation. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:797–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatten G, Bestor T, Balczon R, Henson J, Schatten H. Intracellular pH shift leads to microtubule assembly and microtubule-mediated motility during sea urchin fertilization: correlations between elevated intracellular pH and microtubule activity and depressed intracellular pH and microtubule disassembly. Eur J Cell Biol. 1985;36:116–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel A. Stathmin: a relay phosphoprotein for multiple signal transduction? Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:301–305. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90123-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittle CS, Cassimeris L. Mechanisms blocking microtubule minus end assembly: evidence for a tubulin dimer-binding protein. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1996;34:324–335. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)34:4<324::AID-CM7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournebize R, Andersen SSL, Verde F, Doree M, Karsenti E, Hyman A. Distinct roles of PP1 and PP2A-like phosphatases in control of microtubule dynamics during mitosis. EMBO J. 1997;16:5537–5549. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez RJ, Howell B, Yvon AC, Wadsworth P, Cassimeris L. Nanomolar concentrations of nocodazole alter microtubule dynamic instability in vivo and in vitro. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:973–985. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RA, O’Brien ET, Pryer NK, Soboeiro MF, Voter WA, Erickson HP, Salmon ED. Dynamic instability of individual, MAP-free microtubules analyzed by video light microscopy: rate constants and transition frequencies. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1437–1448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]