Abstract

Undisputed anthropoids appear in the fossil record of Africa and Asia by the middle Eocene, about 45 Ma. Here, we report the discovery of an early Eocene eosimiid anthropoid primate from India, named Anthrasimias, that extends the Asian fossil record of anthropoids by 9–10 million years. A phylogenetic analysis of 75 taxa and 343 characters of the skull, postcranium, and dentition of Anthrasimias and living and fossil primates indicates the basal placement of Anthrasimias among eosimiids, confirms the anthropoid status of Eosimiidae, and suggests that crown haplorhines (tarsiers and monkeys) are the sister clade of Omomyoidea of the Eocene, not nested within an omomyoid clade. Co-occurence of Anthropoidea, Omomyoidea, and Adapoidea makes it evident that peninsular India was an important center for the diversification of primates of modern aspect (euprimates) in the early Eocene. Adaptive reconstructions indicate that early anthropoids were mouse–lemur-sized (≈75 grams) and consumed a mixed diet of fruit and insects. Eosimiids bear little adaptive resemblance to later Eocene-early Oligocene African Anthropoidea.

Keywords: early Eocene, Eosimiidae, India, Primates, paleontology

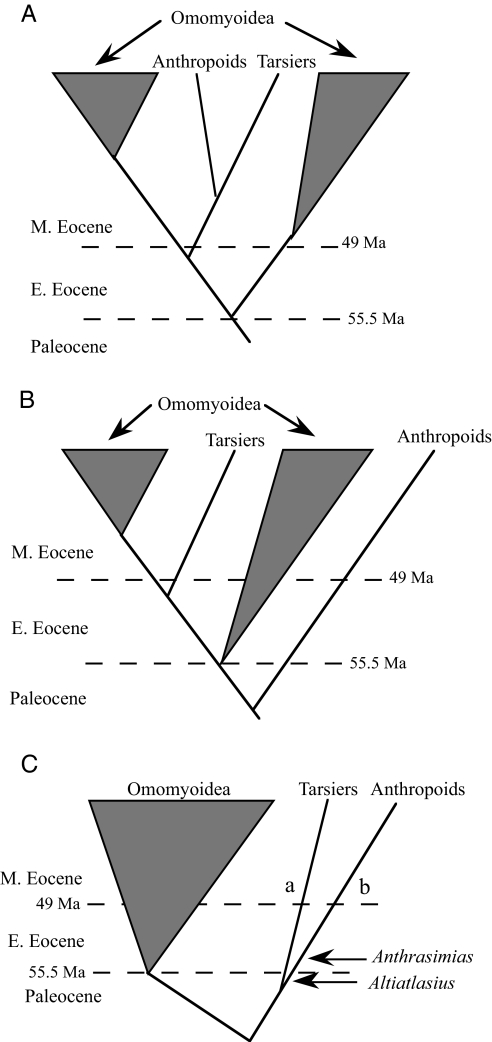

The timing and geographic origins of the Anthropoidea (monkeys, apes, and humans) and the more inclusive crown clade Haplorhini (tarsiers and anthropoids) are poorly understood (1). Some hypothesize that crown haplorhines arose from a single common ancestor within a paraphyletic Eocene Omomyoidea (2) (Fig. 1A). Others suggest that tarsiers arose from a group of Eocene omomyoids, but that anthropoids stem from a separate group, the Eosimiidae, sister to omomyoids (Fig. 1B) (3). A third alternative, not previously advocated, is that crown haplorhines are sister to Omomyoidea as a whole (Fig. 1C). If the first hypothesis is correct, then the anthropoid stem could be as young as middle Eocene, when eosimiids first are recorded. However, if the second or third hypothesis is correct, haplorhine (and anthropoid) origins must be sought in the Paleocene or earlier. Here, we report the discovery of an early Eocene eosimiid anthropoid primate, named Anthrasimias, that is the first from peninsular India and extends the Asian fossil record of anthropoids by 9–10 million years. Anthrasimiasoccurs at the same stratigraphic level as basal representatives of Eocene primate groups Omomyoidea and Adapoidea (4–6), making it evident that India was an important center for the evolution of primates of modern aspect in the early Eocene. A new phylogenetic analysis supports the hypothesis that the Eosimiidae are stem anthropoids (7–9) and suggests that crown haplorhines are sister to a monophyletic Eocene Omomyoidea rather than being nested within omomyoids (10, 11).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representations of three hypotheses about anthropoid and tarsier origins. (A) Anthropoids and tarsiers share a common ancestor within a paraphyletic Omomyoidea. (B) Tarsiers arose from an omomyoid while anthropoids are sister to omomyoids. (C) The tarsier-anthropoid clade is the sister group of omomyoids. References to these views are in the text. Constraints on the branch times of the groups depicted in these schemes are approximate and based on the first appearance of (i) Omomyoidea [earliest Eocene (40)], (ii) Tarsiidae [middle Eocene (41)] or the omomyoid Shoshonius, its proposed sister taxon (22), and (iii) middle Eocene or earlier anthropoids, depending on the assumptions of various authors. Dashed lines represent the dates of the Paleocene-Eocene and early Eocene-middle Eocene boundaries (42). Temporal position of Altiatlasius and Anthrasimias are indicated. a, first appearance of Tarsiidae in Asia; b, hitherto first appearance on eosimiid anthropoids in Asia.

As the antiquity of the anthropoid lineage deepens, questions about major adaptive shifts that are relevant to anthropoid origins are beginning to converge on questions about the origins of the Order Primates as a whole. It is becoming apparent that information about the basal members of each of the major Eocene groups, Anthropoidea, Omomyoidea, and Adapoidea, should contribute significantly to our reconstructions of ancestral primates. It has been hypothesized that the earliest primates dwelt in fine-branch thickets, were ≤200 g in body mass, and had a mixed diet of fruit and insects, gleaned by visual predation (12, 13). However, recent estimates based on extant arboreal primates place the ancestral body mass of crown primates at ≥1 kg (14), which is outside the range of extant insectivorous primates (15). Body mass reconstruction of 1 kg for ancestral primates tends to rule out the visual predation hypothesis and supports, by implication, an alternative hypothesis that links novel primate adaptations with the coevolution of angiosperms (16). In addition to Anthrasimias, four other basal primates are known from the same stratigraphic level in the Vastan mine and represent Omomyoidea (Vastanomys, Suratius, compare with Omomyoidea) and Adapoidea (Marcgodinotius and Asiadapis) (4–6). Reconstructions of body mass and diet for these and other eosimiid taxa addressed in this article shed light on the alternative adaptive hypotheses.

Systematic Paleontology

Primates, Linnaeus, 1758; Anthropoidea, Mivart, 1864; Eosimiidae, Beard et al., 1994

Anthrasimias, Gen. Nov.

Etymology.

After anthra, Greek for coal, because the fossils were found in a coal mine; simias, Latin for monkey or ape.

Diagnosis.

As for type species.

Anthrasimias gujaratensis Sp. Nov.

Etymology.

After Gujarat state of western India, the provenance of this species.

Holotype.

IITR/ SB/VLM 1137, a left M1 (Fig. 2 A and C).

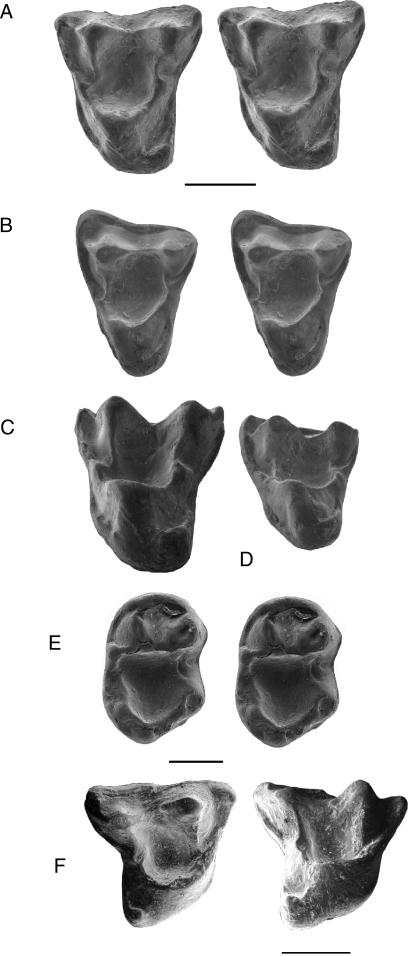

Fig. 2.

The dentition of Anthrasimias gujaratensis sp. nov. (A) Occlusal stereopair of IITR/SB/VLM 1137, a left upper first molar. (B) Occlusal stereopair of IITR/SB/VLM 1100, a left upper second molar. (C) Lingual view of IITR/SB/VLM 1137. (D) Lingual view of IITR/SB/VLM 1100. (E) Occlusal stereopair of IITR/SB/VLM 1017, a right lower third molar. (F) occlusal and occluso-lingual view of IITR/SB/VLM 1201, a right dP4. (Scale bars, 1 mm.)

Hypodigm.

IITR/SB/VLM 1100, a left M2 (Fig. 2 B–D), IITR/ SB/VLM 1017, a right M3 (Fig. 2E), IITR/SB/VLM 1201, a dP4 (Fig. 2E).

Horizon and locality.

Early Eocene Cambay Shale, Vastan Lignite Mine, Surat District, Gujarat, western India (2). The Anthrasimias stratigraphic level contains a diverse early Eocene terrestrial mammalian fauna (1–3, 17, 18). Age-diagnostic dinoflagellate cysts indicate a basal Eocene (Sparnacian, ca. 54-55 Ma) age for the mammal horizon (19). This estimate is a revision of the earlier age assessment of basal Cuisian, ca. 53 Ma, from shallow benthic foraminifera (4, 6, 20).

Diagnosis.

Equivalent in size to Altiatlasius (of Africa) and the smallest Asian eosimiids with described dental remains. Differs from eosimiids in having a more triangular occlusal outline (i.e., less transverse buccolingually) and in having a cuspate hypocone (vs. absent to cristiform). Differs from other eosimiid primates (except Phileosimias kamali) and from Altiatlasius in having less well developed buccal and lingual cingulae. Conules slightly larger than in Eosimias, Phenacopithecus, and Bahinia, but smaller than in Phileosimias.

Comparisons.

Anthrasimias shares with other eosimiids a suite of dental features noted by Beard and Wang (3) to be diagnostic of eosimiids but not found together in omomyoids, including strong development of pre- and postprotocristae, absence of a Nannopithex fold, and reduced conules. The distolingual expansion of the talon, present in Anthrasimias, is common among eosimiids (21). The lingual cingulum of Anthrasimias is incomplete, unlike that of Eosimias, Phenacopithecus, Bahinia, and Phileosimias brahuiorum, but is similar to P. kamali.

The steep incline of the buccal wall of the paracone and metacone in Anthrasimias is common in eosimiids, particularly Eosimias and Phenacopithecus. Like other eosimiids, and especially like Eosimias (and unlike most omomyoids), the parastyle is a large distinct cusp, and the metastyle is present as a swelling along the postmetacrista. The protocone is canted mesially, such that it is closer to the mesial edge of the tooth, as in Eosimias, Bahinia, and Phenacopithecus but not Phileosimias. There is a distinct molar waisting, especially in the area of the metaconule, as in Eosimias, Phenacopithecus, and Bahinia, but less markedly in Phileosimias.

Eosimiids generally lack metaconule cristae and a postparaconule crista. Instead, the postprotocrista leads to the base of the metacone or to a small metaconule that connects in turn with a hypometacrista. Anthrasimias has an intermediate morphology: the postprotocrista is straight, not distally bowed, and connects with the metaconule, which sends a strong but buccally directed premetaconule crista up the lingual aspect of the metacone. We interpret this arrangement of the premetaconule crista as a precursor to the hypometacrista.

Several notable features of the M3 are eosimiid-like: the trigonid is open lingually and supports a small centrally placed paraconid, the protocristid is transverse, and the hypoconulid is small and does not project posteriorly as a distinct distal lobe.

Altiatlasius (late Paleocene, Africa) exhibits some but not all of the above-mentioned symplesiomorphies with Anthrasimias and other eosimiids. Like eosimiids, the postprotocristae leads to the base of the metacone and the preprotocrista to the paracone. In both Altiatlasius and eosimiids, a Nannopithex fold is absent, and like most eosimiids (but not Anthrasimias), there is a complete lingual cingulum. The steep incline of the buccal wall of the paracone and metacone in Altiatlasius also is common in eosimiids. Furthermore, like Anthrasimias and other eosimiids, especially Eosimias (and unlike most omomyoids), the preparacrista and postmetacrista are angled buccally and supported by a large parastyle and somewhat smaller metastyle, respectively. However, unlike Anthrasimias and other eosimiids, the talon of Altiatlasius is not noticeably expanded distolingually, the protocone is not canted mesially, and the molar waisting is indistinct. Further, Altiatlasius lacks a hypometacrista.

Phylogenetic analysis.

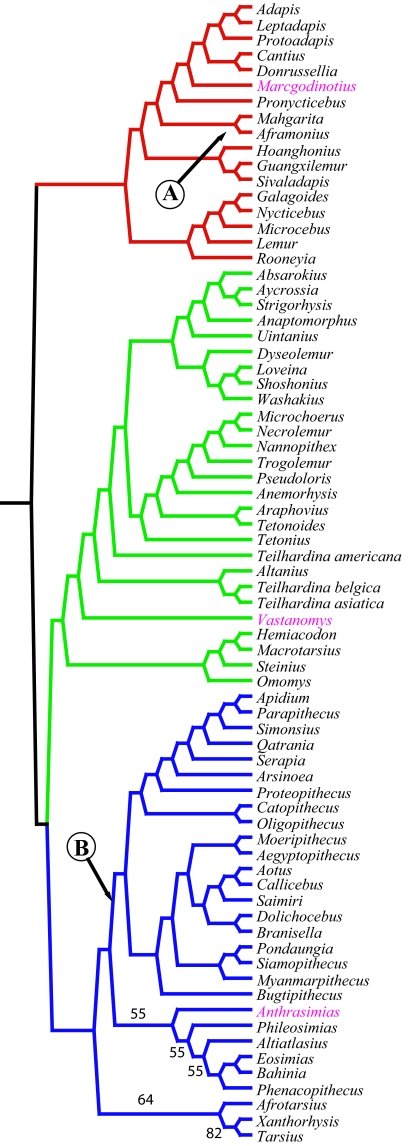

A parsimony analysis was undertaken by using PAUP parsimony software (22) to determine the phylogenetic position of Anthrasimias and other Indian early Eocene primates (Fig. 3). A notable feature of all maximum parsimony trees is that crown Haplorhini is sister to all Omomyoidea, not nested within it as often argued (8, 11, 22).

Fig. 3.

The 50% majority consensus of 11 equally parsimonious trees. Tree length, 148,887; consistency index (CI), 0.230; retention index (RI), 0.554; rescaled CI (RCI), 0.127. Red, Adapoidea; green; Omomyoidea; blue, crown Haplorhini. Branching sequences are supported in 100% of the trees unless indicated by a percentage. Suratius and Asiadapis are not included on the tree. Circled letter A indicates branch placement of Asiadapis when it is run without Suratius included. Circled letter B indicates branch placement of Suratius when Asiadapis is not included. When Suratius and Asiadapis are run together, they are placed together at branch B. The list of characters and their states and character-taxon matrix is provided in supporting information (SI) Text, Figs. S1–S3, and SI Appendices 1 and 2.

All trees place Marcgodinotius near the base of Adapoidea. The latter is a sister taxon to crown Strepsirrhini. Marcgodinotius is similar to the European early Eocene adapoid Donrussellia in many primitive features (5). Vastanomys is placed near the base of the Omomyoidea. Vastanomys is primitive for omomyoids in retaining a large canine and a large, although single-rooted, P2 (5). It appears to be more primitive than North American Steinius, argued by some to be the most primitive omomyoid (24).

The 50% majority consensus tree places Anthrasimias at the base of the eosimiids. A plausible alternative places this taxon at the base of the tarsiid clade or in an unresolved trichotomy with tarsiids and eosimiids. The eosimiid placement is consistent with morphological characters, mentioned in the diagnosis above, considered most critical to reconstructing eosimiid evolution (3, 25). All trees also support placement of Altiatlasius with the Eosimiidae (10, 26, 27).

The phylogenetic position of late Eocene amphipithecids of Asia is a subject of considerable debate. Mandibular and dental similarities and the structure of an isolated talus suggest an anthropoid association (28, 29). In this analysis, we accept the view that some other isolated bones allocated to this taxon are not primate or belong to a large strepsirrhine (30, 31). Our analysis using dental, gnathic, and talar characters supports placement of amphipithecids within Anthropoidea.

The analysis is equivocal concerning placement of Asiadapis and Suratius. Phylogenetic analysis of all taxa in our dataset links the two and places them at the base of the noneosimiid Anthropoidea. In separate analyses, however, Asiadapis, considered alone without Suratius, falls with adapoids Aframonius and Mahgarita, whereas Suratius, run alone without Asiadapis, is linked with eosimiids.

Adaptations.

Our findings of very small body size in basal members of all radiations indicate that insects rather than plants were the primary source of protein for early primates (Table 1) (32). There is no support for the hypothesis that basal Anthropoidea were large, despite the relatively large size of most Oligocene-Recent species (15). Anthrasimias, at 75 g, was smaller than all living primates with the exception of some species of Galagoides (the dwarf galago) and Microcebus (the mouse lemur) (Table 1). No size trends are evident among eosimiids. Anthrasimias (and African Altiatlasius) were slightly smaller than middle to late Eocene Asian eosimiids known from dental material (85–150 g), but some tarsal bones suggest that some middle Eocene eosimiids may have been shrew-sized (33). Likewise, Vastan omomyoids and adapoids were very small animals: Vastanomys and Marcgodinotius ranged up to 130 g. Suratius and Asiadapis were slightly larger, up to 270 g. Thus, early Eocene members of the three radiations of crown primates, omomyoids, stem strepsirrhines, and crown haplorhines also weighed <300 g.

Table 1.

Body mass estimates for Eocene and early Oligocene South Asian primates (Thailand, Myanmar, Pakistan, India) and representative early taxa of early Eocene Omomyoidea and Adapoidea

| Taxon | Age | M2 length | M1 area | Our estimate body weight, g | Previous estimates (Ref.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adapoidea | |||||

| Marcgodinotius indicus(n = 2) | Early Eocene | 2.23 | — | 132 | — |

| Asiadapis cambayensis | Early Eocene | 2.83 | — | 270 | — |

| Donrussellia provincialis | Early Eocene | 2.3 | 5.67 | 144, 74 | 40 g (43) |

| Superfamily affinity uncertain | |||||

| Suratius robustus | Early Eocene | 2.75 | — | 248 | — |

| Altanius orlovi | Early Eocene | 1.2 | 1.78 | 17, 10 | 10 g-30 g (44) |

| Omomyoidea | |||||

| Teilhardina belgica | Early Eocene | 1.73 | 4.29 | 61, 46 | 30–90 (44) |

| Teilhardina asiatica | Early Eocene | 1.78 | 4.68 | 67, 54 | 28 g |

| Steinius vespertinus | Early Eocene | 2.18 | — | 122 | 298 g |

| Vastanomy gracilis | Early Eocene | 2.06 | 5.90 | 103, 80 | — |

| Eosimiidae | |||||

| Altiatlasius koulchii | Late Paleocene | 1.76 | 3.38 | 31, 64 | — |

| Anthrasimias gujaratensis | Early Eocene | — | 5.68 | 75 | — |

| Eosimias sinensis | Middle Eocene | 1.85 | — | 75 | 67–137 (3); 140 (45) |

| Eosimias centennicus | Late middle Eocene | 2.07 (n = 5) | 6.23 | 105, 88 | 64–131 (3); 160 (45) |

| Eosimias dawsonae | Late middle Eocene | 2.40 | — | 164 | 107–276 (3) |

| Bahinia pondaungensis | Late middle Eocene | — | 12.25 | 279 | 570 g (45) |

| Phenacopithecus xueshii | Late middle Eocene | 2.70 | — | 235 | 163–316 g (3) |

| Phenacopithecus krishtalkai | Late middle Eocene | — | 8.50 | 149 | 163–316 g (3) |

| Phileosimias brahuiorum | Early Oligocene | 2.60 | 7.26 | 114, 209 | 250 g (25) |

| Phileosimias kamali | Early Oligocene | 2.60 | 8.60 | 152 | 250 g (25) |

| Amphipithecidae | |||||

| Siamopithecus eocaenus | Late Eocene | 6.26 (n = 2) | 43.7 | — | 5.9 kg (45) |

| Pondaungiaspp. | Late middle Eocene | 6.92 | 33.8 | — | 5,900 g (45) |

| Myanmarpithecus yarshensis | Late middle Eocene | 4.17 | 18.8 | 870, 583 | 1,800 g (45) |

| Bugtipithecus inexpectans | Early Oligocene | — | 7.82 | 129 | 350 g (25) |

A new body mass is not proposed for Pondaungia and Siamopithecus, because such an estimate would be an extrapolation from the size range on which the size estimates are based. The formulae for estimation of body mass in grams for 10 genera of prosimians: from lower second molar length: (3.019 × ln m2 length) + 2.459 with an r2 of 0.458; from upper first molar area: (1.716 × ln M1 area) + 1.333 with an r2 of 0.55.

Previous studies on the diet of fossil anthropoids have relied on comparative evidence from living taxa and the morphology of the lower teeth of anthropoid taxa from the Fayum of Egypt dating back to the late Eocene (34). Those late Eocene anthropoids show a diet that was predominantly frugivorous, but their >750 g body size suggests leaves, not insects, as an important source of dietary protein. However, the 20-million-year separation of Fayum anthropoids from basal members of the anthropoid clade makes them poor candidates from which to infer possible adaptive shifts at the base of the group.

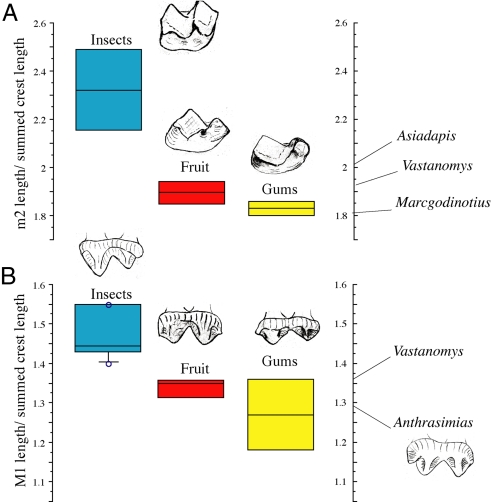

Body mass alone may tell us something about the likely source of dietary protein, but tooth structure gives further details about the relative importance of fruit vs. animal prey. Among small-bodied extant prosimians, a strong relationship exists between the summed lengths of shearing crests of the lower molar teeth and the amount of animal prey in the diet (32). A similar phenomenon occurs with the upper molars (Fig. 4, Table 2). From dental anatomy (combined with small size), we infer that Anthrasimias had a mixed diet of fruit and some insects similar to that of the mouse lemur Microcebus. The development of shearing crests on the upper and/or lower teeth of Asiadapis, Vastanomys, and Marcgodinotius likewise suggests a mixed frugivorous/insectivorous diet. Unlike proposed reconstructions of body mass >1 kg, our body mass and dietary reconstructions of taxa basal to Eocene primate clades provide broadly based evidence that the earliest primates relied, at least in part, on insects or other animal prey. Our conclusion is consistent with the visual predation hypothesis but does not rule out coevolution with angiosperms. There is no evidence to indicate that changes in body mass or diet accompanied the cladogenic splitting of haplorhines from strepsirrhines or anthropoids from omomyoids.

Fig. 4.

Measurements of shearing crest development on the molar teeth of Vastan primates. (A) Ratio of second lower molar length to summed lengths of six principal M2 shearing crests. (B) Ratio of first upper molar length to summed lengths of four principal buccal shearing crests. Color-coded bars (blue, insects; red, fruit; yellow, gums) indicate principal dietary item (34). Asiadapis, Vastanomys, and Marcgodinotius fall within the range of extant prosimian fruit and gum eaters such as the extant mouse lemur Microcebus, which also eats a substantial amount of insects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Diet and shearing crest lengths of extant and extinct primates used in the text

| Taxon | Principal dietary item | Upper molar shearing ratio | Lower molar shear ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arctocebus calabarensis | Insects | 1.55 | 2.18 |

| Galagoides demidoff | Insects | 1.4 | 2.13 |

| Galago maholi | Insects | 1.43 | 2.46 |

| Loris tardigradus | Insects | 1.49 | 2.01 |

| Tarsius spectrum | Insects | 1.46 | 2.52 |

| Tarsius syrichta | Insects | 1.43 | |

| Tarsius bancanus | Insects | 1.55 | |

| Galago alleni | Fruit | 1.3 | 1.94 |

| Microcebus murinus | Fruit | 1.35 | 1.85 |

| Microcebus rufus | Fruit | 1.36 | |

| Perodicticus potto | Fruit | 1.11 | 1.71 |

| Otolemur crassicaudatus | Fruit | 1.22 | 1.69 |

| Euoticus elegantulus | Gums | 1.36 | 1.86 |

| Phaner furcifer | Gums | 1.18 | 1.8 |

| Vastanomys gracilis | 1.32 | 1.91 | |

| Anthrasimias gujaratensis | 1.33 | ||

| Marcgodinotius indicus (n = 2) | 1.81 | ||

| Asiadapis cambayensis | 2.06 |

Temporal and biogeographic implications.

Hitherto, the oldest undisputed eosimiids were recovered from the Chinese middle Eocene (≈45 Ma) (3, 35). Anthrasimias is the first eosimiid from the Indian subcontinent and extends the Asian fossil record of anthropoids by 9–10 million years. Anthrasimias may also be the oldest anthropoid in the world. However, our analysis supports the hypothesis that Altiatlasius from the late Paleocene of Africa is possibly an eosimiid anthropoid (10, 26, 27). Nevertheless, others consider it to be an omomyoid (36), a plesiadapoid (37), or of indeterminate subordinal affinities (1). In any event, the cooccurrence of an anthropoid taxon alongside adapoid and omomyoid primates in the early Eocene of Asia gives further evidence that the cladogenesis of crown haplorhines and strepsirrhines was ancient, in the Paleocene or even Cretaceous, as molecular evidence suggests (14, 38).

The Vastan Indian fauna shows strong links with Laurasian early Eocene faunas (5, 6, 17, 18). The presence of an anthropoid in India before 54 million years ago and possibly even earlier in Africa (if Altiatlasius is an anthropoid) fleshes out the picture of early Cenozoic interchange between Laurasia and Africa (26, 39) and between the Indian and Asian plates, the latter in the context of their tectonic collision (17). The Vastan anthropoid testifies to the early importance of India as an important center for the differentiation of all of the major groups of primates.

Materials and Methods

For the phylogenetic analysis, our dataset consists of 75 taxa and 343 characters of the skull, postcranium, and dentition. It includes a wide representation of Adapoidea, Omomyoidea, Tarsiidae, Eosimiidae, and other stem and crown Anthropoidea. We include Anthrasimias and other early Eocene Indian primates from Vastan: Marcgodinotius, Vastanomys, Suratius, and Asiadapis. We ran the character–taxon matrix in PAUP 4.0b10 (22) with all multistate characters scaled. As described by Swofford (22), weights are assigned to all characters, such that the minimum possible length of each character is 100 (the default “base weight”). Binary characters and unordered characters are assigned a weight of 100, three state ordered characters a weight of 50, and so on. Findings are detailed in Fig. 2.

Previous estimates of body mass in small-bodied fossil primates have been based on regressions derived from a wide range of prosimian taxa, including such large-bodied primates as Propithecus and Varecia. A more appropriate model for these extremely small primates should be based on a sample of small-bodied taxa. To estimate the body mass of Anthrasimias and other eosimiid and amphipithecid taxa, we used a formula derived from the molar size and body mass of 10 genera of extant prosimians weighing <600 g.

To reconstruct diet in our Eocene species, we selected 10 genera of extant tarsiers, galagos, lorises, and dwarf lemurs (14 genera for the lower teeth). We compared the ratio of the summed lengths of six principal lower second molar shearing crests to M2 length. Likewise, we took the ratio of the sum of the four principal buccal shearing crests (preparacrista + postparacrista + premetacrista + postmetacrista) of the upper first molar to M1 length. Findings for Vastan primates are detailed in Fig. 4. Data are summarized in Table 2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Prof. J. G. M. Thewissen for suggestions and comments. R.F.K. and B.A.W. thank Prof. Ken Rose, Laurent Marivaux, Erik Seiffert, and Chris Beard for helpful discussions about Indian and Asian primates. We thank Leslie Eibest for technical assistance and the officers of the Vastan Lignite Mine for facilitating our work. S.B. thanks Chris Beard for discussions and Ranjan Das and Krishna Kumar for help in collecting fossils. S.B. and B.N.T. thank the staff of the scanning electron microscopy laboratories in their institutes. S.B.'s research is funded by the Department of Science and Technology (including the Ramanna Fellowship), Government of India. Research support to R.F.K. and B.A.W. is provided by Duke University Provost's Research Fund. The National Science Foundation supports the scanning electron microscope laboratory, Duke University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0804159105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Miller ER, Gunnell GF, Martin RD. Deep time and the search for anthropoid origins. Yearb Phys Anthropol. 2005;48:60–95. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartmill M, Kay RF. In: Recent Advances in Primatology: Evolution. Chivers DJ, Joysey KA, editors. London: Academic; 1978. pp. 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beard KC, Wang J. The eosimiid primates (Anthropoidea) of the Heti Formation, Yuanqu Basin, Shanxi and Henan Provinces, People's Republic of China. J Hum Evol. 2004;46:401–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajpai S, Kapur VV, Das DP, Tiwari BN. New early Eocene primate (Mammalia) from Vastan Lignite Mine, District Surat (Gujarat), western India. J Paleontol Soc India. 2007;52:231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajpai S, et al. Early Eocene primates from Vastan lignite mine, Gujarat, western India. J Paleontol Soc India. 2005;50:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose KD, Rana RS, Sahni A, Smith T. A new adapoid primate from the early Eocene of India. Contrib Mus Paleontol Univ Michigan. 2007;31:379–385. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beard KC, Qi T, Dawson M, Wang B, Li C. A diverse new primate fauna from middle Eocene fissure-fillings in Southeastern China. Nature. 1994;369:604–609. doi: 10.1038/368604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay RF, Ross CF, Williams BA. Anthropoid origins. Science. 1997;275:797–804. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5301.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beard KC. In: The Primate Fossil Record. Hartwig WC, editor. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2002. pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seiffert ER, et al. Basal anthropoids from Egypt and the antiquity of Africa's higher primate radiation. Science. 2005;310:300–304. doi: 10.1126/science.1116569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kay RF, Williams BA, Ross CF, Takai M, Shigehara N. In: Anthropoid Origins: New Visions. Ross CF, Kay RF, editors. New York: Kluwer/Plenum; 2004. pp. 91–135. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cartmill M. Rethinking primate origins. Science. 1974;184:436–443. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4135.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross CF. Allometric and functional influences on primate orbit orientation and the origins of the Anthropoidea. J Hum Evol. 1995;29:210–228. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soligo C, Martin RD. Adaptive origins of primates revisited. J Hum Evol. 2006;50:414–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kay RF. In: Adaptations for Foraging in Nonhuman Primates. Cant J, Rodman P, editors. New York: Columbia Univ Press; 1984. pp. 21–53. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sussman RW. Primate origins and the evolution of angiosperms. Am J Primatol. 1991;23:209–223. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350230402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajpai S, Das DP, Tiwari BN, Saravanan N, Sharma R. Early Eocene mammals from Vastan lignite mine, District Surat (Gujarat), western India. J Paleontol Soc India. 2005;50:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith T, et al. High bat (Chiroptera) diversity in the Early Eocene of India. Naturwissenschaften. 2007;94:1003–1009. doi: 10.1007/s00114-007-0280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg R, et al. Age-diagnostic dinoflagellate cysts from lignite-bearing sediments of the Vastan lignite mine, Surat District, Gujarat, western India. J Palaeontol Soc India. 2008:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahni A, et al. Temporal constraints and depositional paleoenvironments of the Vastan lignite sequence, Gujarat: Analogy for the Cambay Shale hydrocarbon source rock. Indian J Petrol Geol. 2006;15:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marivaux L, et al. Anthropoid primates from the Oligocene of Pakistan (Bugti Hills): Data on early anthropoid evolution and biogeography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8436–8441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503469102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swofford DL. PAUP. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony, Version 4.0b10 (Altivec) Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beard KC, MacPhee RDE. In: Anthropoid Origins: The Fossil Evidence. Fleagle JG, Kay RF, editors. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 55–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose KD. The earliest primates. Evol Anthropol. 1995;3:159–173. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marivaux L. The eosimiid and amphipithecid primates (Anthropoidea) from the Oligocene of the Bugti Hills (Balochistan, Pakistan): New insight into early higher primate evolution in South Asia. Palaeovertebrata Montpellier. 2006;34:29–109. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beard KC. In: Primate Biogeography. Lehman SM, Fleagle JG, editors. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 439–468. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beard KC. The Hunt for the Dawn Monkey. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciochon RL, Savage DE, Thaw Tint, Ba Maw U. Anthropoid origins in Asia?: New discovery of Amphipithecus from the Eocene of Burma. Science. 1985;229:756–759. doi: 10.1126/science.229.4715.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marivaux L, et al. The anthropoid status of a primate from late middle Eocene Pondaung Formation (central Myanmar): Tarsal evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13173–13178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2332542100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marivaux L, et al. Anatomy of the bony pelvis of a relatively large-bodied strepsirrhine primate from the late middle Eocene Pondaung Formation (central Myanmar) J Hum Evol. 2008;54:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beard KC, et al. Taxonomic status of purported primate frontal bones from the Eocene Pondaung Formation of Myanmar. J Hum Evol. 2005;49:468–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kay RF, Covert HH. In: Food Acquisition and Processing in Primates. Chivers DJ, Wood BA, Bilsborough A, editors. New York: Plenum; 1984. pp. 467–508. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gebo DL, Dagosto M, Beard KC, Tao Q. The smallest primates. J Hum Evol. 2000;38:585–594. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2000.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirk EC, Simons EL. Diet of fossil primates from the Fayum Depression of Egypt: A quantitative analysis of molar shearing. J Hum Evol. 2000;40:203–229. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2000.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beard KC, Wang B, Dawson M, Huang X, Tong Y. Earliest complete dentition of an anthropoid primate from the late middle Eocene of Shanxi Province, China. Science. 1996;272:82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sigé B, Jaeger J-J, Sudre J, Vianey-Liaud M. Altiatlasius koulchii n. gen. et sp., primate omomyidé du Paléocène supérieur du Moroc, et les origines des Euprimates. Paleontographica. 1990;212:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hooker JJ, Russell DE, Phélizon A. A new family of Plesiadapifores (Mammalia) from the Old World lower Paleogene. Palaeontology. 1999;42:377–407. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin RD, Soligo C, Tavare S. Primate origins: Implications of a Cretaceous ancestry. Folia Primatol. 2007;78:277–296. doi: 10.1159/000105145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossie JB, Seiffert ER. In: Primate Biogeography. Lehman SM, Fleagle JG, editors. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 469–522. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beard KC. The oldest North American primate and mammalian biogeography during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3815–3818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710180105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beard KC. A new genus of Tarsiidae (Mammalia: Primates) from the middle Eocene of Shanxi Province, China, with notes on the historical biogeography of tarsiers. Bull Carnegie Mus Nat Hist. 1998;34:260–277. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berggren WA, Pearson PN. A revised tropical to subtropical Paleogene planktonic foraminiferal zonation. J Foramin Res. 2005;35:279–298. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbert CC. Dietary ecospace and the diversity of euprimates during the Early and Middle Eocene. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005;126:237–249. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gingerich PD. Dentition and systematic relationships of Altanius orlovi (Mammalia, Primates) from the early Eocene of Mongolia. Geobios. 1991;24:637–646. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egi N, Takai M, Shigehara N, Tsubamoto T. Body mass estimates for Eocene eosimiid and amphipithecid primates using prosimian and anthropoid scaling models. Int J Primatol. 2004;25:211–236. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kay RF, et al. The paleobiology of Amphipithecidae, South Asian late Eocene primates. J Hum Evol. 2004;46:3–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.