Abstract

A 36-year-old man with a history of primary sclerosing cholangitis and epilepsy was admitted to our hospital for cholangitis. During admission he was resuscitated because of ventricular fibrillation. ECGs showed multiple ventricular premature beats (VPBs) with a short coupling interval (240 ms), resulting in frequent torsade de pointes (TdP). In total, the patient had to be defibrillated 12 times. Short-coupled TdP is a rare variant of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, with unknown aetiology. Verapamil seems to be the only drug able to suppress the arrhythmia. Verapamil, however, does not lower the risk of sudden death; therefore, an ICD implantation is advised. (Neth Heart J 2008;16:246-9.)

Keywords: torsade, pointes, short, coupled, TdP

In April 2007, a 36-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of fever (40 °C), dizziness and stomach ache. His previous medical history revealed primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC, 2005), epilepsy (1985) and a mild colitis for which no medication was used. The epilepsy was diagnosed in 1985 by several consecutive EEGs. On admission an exacerbation of the PSC was diagnosed and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography was performed. The day after admission, the patient collapsed while in the toilet. Resuscitation was started and the automated external defibrillator, attached by the nurses, delivered one shock re-establishing circulation. The patient was admitted to the coronary care unit. In his childhood the patient had experienced seizures, the last syncope, however, was about 20 years before. His family history was negative for sudden cardiac death. The patient was taking ursodiol (for PSC), valproic acid (for epilepsy) and on admission ciprofloxacin (200 mg twice daily) was added. Apart from fever and a painful abdomen, the physical examination showed no (cardiovascular) abnormalities.

The ECG on admission showed sinus rhythm with one ventricular premature beat with a short coupling interval (260 ms), normal QTc (380 ms) and no signs of ischaemia. After admission to the coronary care unit he displayed multiple ventricular premature beats resulting in torsade de pointes (TdP) (figure 1), deteriorating into ventricular fibrillation 12 times. The TdP episodes were non-pause related and the (initiating) premature beats were short coupled, with an interval of 240 to 260 ms (figure 2). The QTc interval was always normal at every heart rate. All the premature beats were monomorphic with a superior axis and a left bundle branch configuration, suggesting an origin inferior in the right ventricle or the left septum.

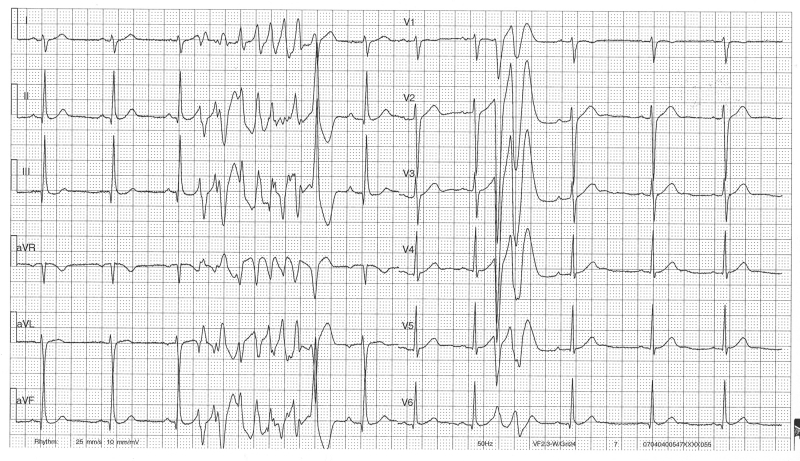

Figure 1.

ECG demonstrating an episode of torsade de pointes. The (initiating) premature beats are short coupled with an interval of 240 to 260 ms.

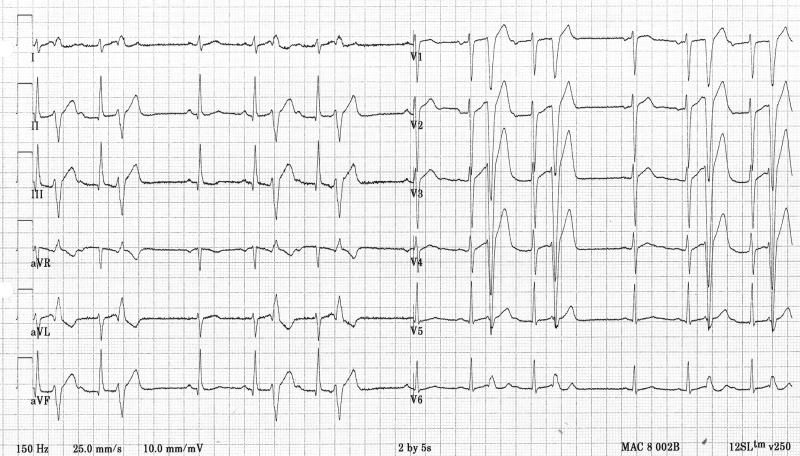

Figure 2.

ECG demonstrating monomorphic ventricular premature beats with a superior axis and a left bundle branch configuration, suggesting an origin inferior in the right ventricle or the left septum. Again notice the short coupling interval.

Extensive laboratory studies revealed a potassium of 3.0 mmol/l, but no other abnormalities. Echocardiography was performed and demonstrated no structural abnormalities.

The patient was initially treated with magnesium and amiodarone with no effect. After the short-coupled variant of torsade de pointes was recognised, the electrical storms were treated on the ICU with esmolol and sedation using benzodiazepines to reduce the arrhythmias. Eventually verapamil was commenced, which resulted in a complete disappearance of the ventricular ectopy.

An electrophysiological examination was performed. No ventricular premature beats were inducible, so the initiating focus could not be ablated at that time. Ultimately, the patient received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). The patient remained on verapamil and has not received any shocks to date (follow-up six months).

Discussion

TdP was first described by Dessertenne in 1966 as a ventricular tachycardia characterised by changing amplitude of the complexes with a characteristic twist around the isoelectric baseline.1 TdP is associated with long QT syndromes, both inherited (LQTS 1-8, JLN 1-2) and acquired (drugs, electrolyte disturbances). The initiation of TdP in the most common forms of inherited LQTS has recently been reported.2 TdP initiation is not pause-dependent in LQTS1, but it is in LQTS2, i.e., the RR intervals that initiate TdP exhibit a ‘short-long-short’ sequence. Because acquired LQTS shares the same pathophysiological basis as LQTS2 (reduction in the rapid component of the repolarising delayed rectifier potassium current, IKr, by drugs or electrolyte imbalances), TdP initiation is also pause-dependent in acquired TdP. The cellular mechanisms involved in the occurrence of TdP have been extensively investigated during the last decades. Several reports describe early after-depolarisations (EADs) as a potential trigger for the development of TdP.3 When reaching the threshold, EADs cause ventricular premature beats.3

The short-coupled variant of TdP is a rarely described cause of ventricular tachycardia.4-6 Literature describes healthy young patients who often have a positive family history for sudden cardiac death.5-7 Yet, the responsible gene(s) have not yet been resolved. In one patient, mutations in the cardiac sodium channel encoding gene SCN5A (analysed because of the differential diagnosis of Brugada syndrome) were not found.6The most common first symptom is syncope. The ECG displays typical TdP with a remarkably short coupling interval (always less then 300 ms) of the first TdP beat5. Also, all the ventricular premature beats display this short interval. A short-long-short sequence of RR intervals is not present. TdP is usually noninducible during electrophysiological studies.5 In our patient, as in previously reported cases, all ventricular premature beats where monomorphic and had the same morphology (left bundle branch block, left/ superior axis) as the initiating beat of TdP, suggesting one focal origin which triggers the TdP. Literature on idiopathic ventricular fibrillation shows us the possibility of eliminating recurrent episodes by catheter ablation in patients with a monomorphic trigger.8 Therefore, at least theoretically, catheter ablation should be considered as an option.

Although there is little evidence available, the slow calcium channel blocker verapamil seems to be the only drug with some efficacy in suppressing the arrhythmias, while amiodarone, β-blockers, and quinidine are ineffective. This supports the theory of EADs being the trigger for TdP, since EADs are in part probably carried by current passing through slow calcium channels. Yet, one study suggested that the IKr blocker nifekalant may suppress arrhythmia inducibility by prolonging repolarisation, arguing against a causal role of EADs.6 Either way, verapamil does not seem to reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death; therefore ICD implantation is advised.5

Leenhart et al. described 14 patients with the shortcoupled variant of TdP. In a mean follow-up period of seven years, six patients died (five suddenly). Three of these five patients were being treated with verapamil, two were on β-blockers and none of them had an ICD.5

Although the epilepsy of our patient was well documented on EEG, the question remains whether his ‘seizures’ were not, in reality, the effects of cardiac arrhythmias. Epilepsy has been associated with sudden death (sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: SUDEP). Both bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias related to epileptic seizures have been rarely described.9 Bridging evidence linking epilepsy to cardiac arrhythmias, however, still needs more research.9 Our patient had not had a seizure for at least 20 years.

Literature search does not show a relation between PSC and ventricular tachycardia. Several reports are written on fever triggering or unmasking (previously unknown) Brugada syndrome, resulting in tachyarrhythmias. 10,11 We are not aware of studies linking fever to QTc-related arrhythmias, let alone this shortcoupled variant of TdP. Both hypokalaemia and ciprofloxacin are known causes of QTc prolongation, but, to the best of our knowledge, have never been described in relation to the short-coupled variant of TdP, in contrast to several other antibiotics which are associated with TdP, with or without a prolonged QTc interval.12,13

In conclusion, short-coupled TdP is a rare variant of a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia of unknown aetiology which often results in ventricular fibrillation. Verapamil is the only drug with some ability to suppress the arrhythmia, but as it does not reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death an ICD is advised.

References

- 1.Dessertenne F. Ventricular tachycardia with two variable opposing foci. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 1966;59:263-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan HL, Bardai A, Shimizu W, Moss AJ, Schulze-Bahr E, Noda T, et al. Genotype-specific onset of arrhythmias in congenital Long QT syndrome: possible therapy implications. Circulation 2006;114:2096-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta A, Lawrence AT, Krishnan K, Kavinsky CJ, Trohman RG. Current concepts in the mechanisms and management of druginduced QT prolongation and torsade de pointes. Am Heart J 2007;153:891-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg SJ, Scheinman MM, Dullet NK, Finkbeiner WE, Griffin JC, Eldar M, et al. Sudden cardiac death and polymorphous ventricular tachycardia in patients with normal QT intervals and normal systolic cardiac function. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:687-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leenhardt A, Glaser E, Burguera M, Nurnberg M, Maison-Blanche P, Coumel P. Short-coupled variant of torsade de pointes. A new electrocardiographic entity in the spectrum of idiopathic ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Circulation 1994;89:206-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiga T, Shoda M, Matsuda N, Fuda Y, Hagiwara N, Ohnishi S, et al. Electrophysiological characteristic of a patient exhibiting the short-coupled variant of torsade de pointes. J Electrocardiol 2001; 34:271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamazaki M, Osaka T, Yokoyama E, Kodama I. A case of shortcoupled variant of torsade de pointes characterized by spatial hetereogeneity of action potential duration and its restitution kinetics. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2006;17:35-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haïssaguerre M, Shoda M, Jaïs P, Nogami A, Shah DC, Kautzner J, et al. Mapping and ablation of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Circulation 2002;106:962-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nashef L, Hindocha N, Makoff A. Risk factors in sudden death in epilepsy (SUDEP): the quest for mechanisms. Epilepsia 2007;48:859-71. Epub 2007 Apr 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antzelevitch C, Brugada R. Fever and Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2002;25:1537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller DI, Rougier JS, Kucera JP, Benammar N, Fressart V, Guicheney P, et al. Brugada syndrome and fever: genetic and molecular characterization of patients carrying SCN5A mutations. Cardiovasc Res 2005;67:510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MH, Berkowitz C, Trohman RG. Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with a normal QT interval following azithromycin. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2005;28:1221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chennareddy SB, Siddique M, Karim MY, Kudesia V. Erythromycin-induced polymorphous ventricular tachycardia with normal QT interval. Am Heart J 1996;132:691-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]