Abstract

Heart failure (HF) in older adults presents challenges which are different in many ways than those for younger adults. Diagnosis of HF in older adults can be delayed due to attributing early symptoms to normal changes of aging, or in the setting of a normal ejection fraction, failing to appreciate diastolic heart failure. Moreover, treatment of HF in the elderly is often complicated by comorbidities and polypharmacy. The long-term care setting can present even more challenges, yet can be made easy by following a simple mnemonic DEFEAT-HF. After making a clinical Diagnosis and determining the Etiology, Fluid volume must be assessed to achieve euvolemia, and Ejection frAction must be determine to guide Therapy.

Keywords: Chronic heart failure, nursing home, assessment, management

Heart Failure: A Long-Term Care Syndrome

HF is a complex cardiac syndrome in any age group. However, geriatric HF is more complex as most of these patients suffer from concomitant functional and cognitive limitations, multiple morbidities, and polypharmacy. Over 80% of an estimated 5 million HF patients in the United States are 65 years of age and older and HF is the leading cause of hospital admission in this age group.1 Cardiovascular disease is single largest diagnostic category in the long-term care setting.2 Although the precise prevalence of HF in the long-term care settings is unknown, a significant number of an estimated 2 million long-term care residents 65 years and older in the United States have HF. Thus HF is also a major long-term care syndrome, made even more complex by concomitant functional and cognitive limitations, comorbidities, and polypharmacy, which are more prevalent in the long-term care settings.3, 4 This complexity and the lack of scientific evidence and guideline recommendations specific to this population make assessment and management of HF in the long-term care setting challenging. In addition, patient and family preferences and variations in clinician practice patterns may result in poor quality of care in elderly HF patients in the long-term care setting.5, 6

Long-Term Care Heart Failure: Case Scenarios

Case 1

An 81-year-old white man with a history of hypertension and old myocardial infarction was recently hospitalized after progressive dyspnea. In the six months prior to hospital admission, he developed dyspnea on minimal exertion, orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. Prior to this he was rather physically active. He also developed leg swelling and gained about 10 pounds in weight. He ignored his symptoms, did not call in for a clinic appointment or go to an emergency room. He was directly hospitalized from his primary care physician’s office after a routine visit. He denied chest pain, cough, wheezing, or dizziness. His vital signs were stable. At 45 degrees, the top of his jugular venous pulsation was about 4 cm from the sternal angle and there was a positive hepatojugular reflux. He also had a right-sided third heart sound, best appreciated at the left sternal border, and pulmonary râles at both lung bases. During his five-day hospital stay, he once became somewhat confused and mostly rested in bed. He responded nicely to intravenous diuretics, regained his baseline weight, and was sent to a nursing home for reconditioning and rehabilitation. His electrocardiogram showed Q wave in the chest leads, and his initial chest x-ray finding of pulmonary congestion was cleared before discharge. An echocardiogram done in the hospital showed an ejection fraction of 35%. Before discharge his serum creatinine was 1.8.mg/dL and his serum potassium was 3.8 mEq/L. His discharge medications included furosemide 40 mg every morning, metoprolol tartrate 12.5 mg twice a day and verapamil 180 mg once a day that he had been taking for his high blood pressure.

Case 2

A 76-year-old African American woman who is a bed- and wheel chair-bound long-term care resident for the past 3 years had two recent hospital admissions for worsening HF. She has diastolic HF, which is clinical HF in the presence of normal or near normal ejection fraction. An echocardiogram from her last hospital admission showed her left ventricular ejection fraction to be >55%. She also has a history of hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, emphysema, and right hemi-paresis from prior stroke. Over the past several weeks, she has been showing signs of dyspnea and fatigue on minimal exertion such as moving in and out of the bed to wheel chair, or changing clothes. She has no dyspnea at rest, and reports no orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. However, she sleeps in a hospital bed, the head end of which is already raised about 45 degrees. Daily weights are not routinely recorded due to her difficulty getting up on a scale. On a physical examination, she was tachypneic with a blood pressure of 180/65 mm Hg and a heart rate of 98 beats per minute. She refused to be moved to the bed for an examination of her jugular venous pressure. However, her external jugular veins were distended bilaterally while she was sitting on her wheel chair. On the right side it did not show any pulsation, but pulsations could be seen at her left external jugular vein about 7–8 cm above her sternal angle. A compression of her abdomen caused distension of her left external jugular vein that lasted for most of the 10 second duration of the compression. This confirmed that her left external jugular vein was connected to the right atrium and could be reasonably used to estimate her jugular venous pressure. She also had a right-sided third heart sound but no pulmonary râles or wheezing. She has a history of chronic leg edema from venous insufficiency. An accentuated second heart sound at left fifth intercostal space suggested pulmonary hypertension, with an estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 45–50 mm Hg. Her electrocardiogram was normal and chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly but no pulmonary congestion. Her serum creatinine and potassium are respectively 1.4 mg/dL and 4 mEq/L. In addition to her insulin and bronchodilators, she is also on torsemide 40 mg daily, potassium chloride 10 mEq twice a day, lisinopril 10 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, and digoxin 0.25 mg daily.

DEFEAT-ing Heart Failure in the Long-Term Care Setting

An understanding of the assessment and management of geriatric HF can be the basis of a solid foundation for good care of HF patients in the long-term care settings. Care for HF in older adults in the long-term care setting can be simplified by following the simple mnemonic “DEFEAT”- HF.7 DEFEATstands for Diagnosis, Etiology, Fluid volume, Ejection frAction, and Treatment (Table 1). The process of HF care in the long-term care setting should begin with a clinical Diagnosis of HF, followed by an assessment of Etiologies for HF. Assessing Fluid volume and achieving fluid balance is the most important clinical goal for both patients’ quality of life and reducing hospital admission. Ordering an echocardiogram to know the left ventricular Ejection frAction is the single most important laboratory test once a diagnosis of HF is established. Although major guidelines provide few evidence-based recommendations for HF patients in the long-term care settings, and Treatment must be individualized, it is important to be familiar with one of the major HF guidelines.6, 8, 9

Table 1.

DFEAT Heart Failure

| D = Diagnosis. | Make a clinical diagnosis of heart failure before ordering any test, especially an echocardiogram. A normal ejection fraction in a patient without a clinical diagnosis may confound the diagnosis process. If a clinical diagnosis is already made or patient had hospitalization due to heart failure, check how the diagnosis was established. |

| E = Etiology | Hypertension and myocardial infarction are the two most common causes. Expect multiple causes in elderly heart failure patients in the long-term care setting. Continued treatment of risk factors such as high blood pressure and myocardial ischemia is important to prevent disease progression. |

| F = Fluid volume | Single most important physical examination. Best assessed by estimating jugular venous pressure in the neck. External jugular veins are very useful if there limitations are appreciated. Being superficial veins they are subject to external pressure or internal obstruction. Thus a distended external jugular vein without visible pulsation should not generally be used to estimate venous pressure. |

| EA = Ejection frAction | Single most important test after a clinical diagnosis of heart failure has been made. It is a marker of prognosis (generally patients with lower ejection fraction had poorer prognosis) and a guide to therapy. |

| T = Treatment | Heart failure therapy can be divided into symptom-relieving and life-prolonging therapies. The two most important life-prolonging therapies for heart failure patients with low ejection fraction (<45%) are ACE inhibitors (or an ARB if intolerant to ACE inhibitor) and beta-blockers (those approved for use in heart failure and shown to reduce mortality, namely metoprolol extended release and carvedilol). Survival benefit of these drugs in diastolic heart failure has not yet proven. All symptomatic heart failure patients with fluid volume overload should be treated with diuretic and once euvolemia is achieved the lowest possible dose should be used to maintain euvolemia in conjunction with salt and fluid restriction. Digitalis in low doses (0.125 mg or less per day) should be used to reduce symptoms and risk of hospitalization. In patients who are cannot tolerate beta-blockers at low dosages digitalis can also reduce mortality. |

Diagnosis of Heart Failure

HF is a clinical diagnosis. HF cannot be definitively diagnosed by any laboratory tests. This makes the diagnosis of HF challenging. A clinical diagnosis of HF depends on a constellation of symptoms, signs and other findings. Our Case 1 is a rather newly diagnosed HF patient who is also new in the long-term care setting. He already had one episode of HF requiring hospitalization, thus a diagnosis of HF has already been established. More importantly the collection of his symptoms and signs before his hospital admission are suggestive of clinical HF. However, whenever possible it is useful to verify the history of initial HF symptoms. Our Case 2 also had known HF, a frequent diagnosis in the long-term care setting. Therefore, the process of establishing a new clinical diagnosis is often not necessary. However, residents of long-term care facilities without HF may develop new-onset HF, requiring the clinician to make a diagnosis. Because long-term care residents may not often be physically active, a history of dyspnea on exertion may not always be available, and their symptoms may progress to dyspnea at rest.3, 10 A history of dyspnea on exertion or fatigue may need to be elicited by asking questions about their routine daily activities such as moving in and out of the wheel chair instead of how many blocks one can walk.

Etiology of Heart Failure

Hypertension and coronary artery disease are the two most common risk factors for HF in older adults.11 Other less common risk factors are chronic kidney disease, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and valvular heart disease. Because HF is a syndrome and not a disease, almost always it is caused by one of these risk factors, which can often be determined during history or chart review. Our Case 1 had a history of both hypertension and myocardial infarction, both potential risk factors. Our Case 2 had hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and atrial fibrillation, all potential causes of HF. It is important to identify underlying risk factors even if they are not the specific etiology of the HF. For example, uncontrolled blood pressure or ongoing myocardial ischemia that may or may not have caused the initial HF may cause significant myocardial damage to the failing heart. This may lead to disease progression, precipitate acute HF, and increase risks of death and hospitalizations.

Normally, when an underlying etiology cannot be found or an ongoing insult such as myocardial ischemia is identified, it is recommended that patients should be referred to a cardiologist. However, in the long-term care setting, a decision of cardiology referral for identification of an etiology needs to be individualized depending on patient and family preferences, and the patient’s overall health and prognosis. However, for patients with ongoing myocardial ischemia, medical therapy should be optimized even if they refuse invasive diagnostic and/or therapeutic procedures, or a cardiology referral is not made for some other reason. Non-adherence to instructions for salt and fluid restriction, and medications may precipitate acute HF. In particular the use of table salt should be discouraged. However, a too restrictive salt regimen may lead to malnutrition and weight loss and should be carefully avoided. Efforts to identify such exacerbating factors should be done in patients with repeated hospitalizations as in Case 2.

Fluid Volume Management in Heart Failure

HF patients with fluid volume overload often experience dyspnea and fatigue, and have poor quality of life. Protracted cases of fluid volume overload may lead to decompensation and hospital admission. Moreover, patients with fluid volume overload often cannot tolerate initiation or continuation of life-saving drugs such as a beta blocker or an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor.

Euvolemia is a key goal in HF management and can often be achieved with proper assessment of fluid volume and appropriate diuresis. However, a proper fluid volume assessment is essential for optimal fluid volume management. While an elevated jugular venous pressure is a sensitive marker of fluid overload,9 this important component of the physical examination is often done improperly, in part due to several myths.

The first myth is that only the internal jugular vein is useful in the estimation of jugular venous pressure. From an anatomic point of view, the internal jugular veins would be ideal for the estimation of jugular venous pressure. However, also from an anatomic point of view, internal jugular veins are very difficult to use for the estimation of jugular venous pressure in chronic HF because for most of their course in the neck they lie behind the largest group of muscles in the neck, the sternocleidomastoids. Therefore, internal jugular veins tend to underestimate jugular venous pressure in both chronic and acute HF.12–14 External jugular veins, on the other hand, are easily visible, and can be more practical alternative vein for the estimation of jugular venous pressure as long its limitations are understood.15

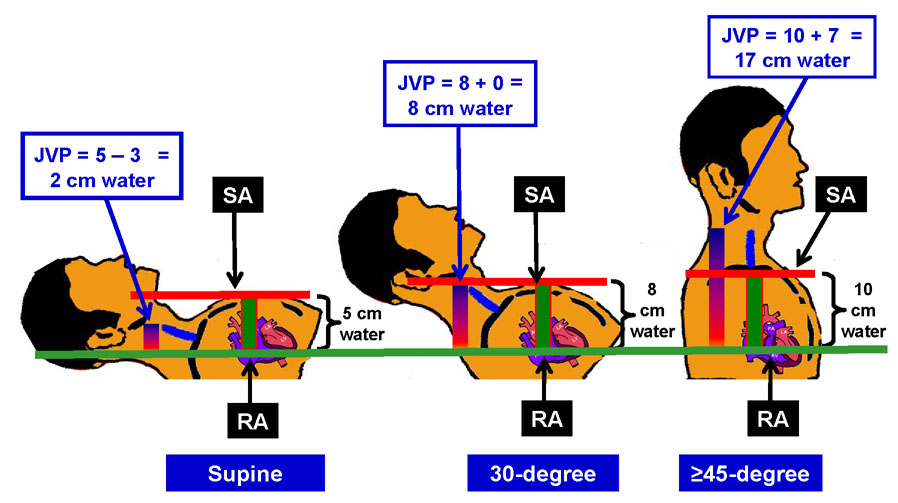

The second myth about jugular venous pressure estimation is that patients need to be positioned at 45 degrees incline and that the distance between right atrium and sternal angle is always 5 cm regardless of body position. While a visible jugular pulsation in the neck at 45 degrees would suggest elevated jugular venous pressure, it is not very useful when the pressure is too high (when the top of the jugular pulsation may be behind the angle of jaw) or too low (when he top of the jugular pulsation would be behind the clavicle). Therefore, patients need to be in supine or sitting position or any other position in between, so that the top of the venous pulsation can be seen and its distance from the right atrium can be estimated. Once the top of the jugular venous pulsation is identified, its distance from the sternal angle should be estimated (Figure 1). If the top of the jugular pulsation is above the level of the sternal angle, that distance should be added to the estimated distance between the sternal angle and right atrium. However, if the top of the jugular pulsation is below the level of the sternal angle, this distance should be subtracted from the estimated distance between the sternal angle and right atrium.

Figure 1.

Estimation of jugular venous pressure (JVP=jugular venous pressure; RA=right atrium; SA=sternal angle)

The third myth is about the distance between right atrium and the sternal angle. It has often been taught in text books, class rooms and at bed side that the distance between right atrium and sternal angle is 5 cm regardless of body position. However, a study based on chest CT scans of chest of 160 patients has determined that the distance between right atrium and sternal angle would be 5 cm only in the supine position.16 However, at 30 and at ≥45 degrees of elevations, this distance would be 8 and 10 cm respectively (Figure 1).

For example, in Case 1, the external jugular venous pulsation was about 4 cm above the sternal angle at 45 degree elevation. At this elevation, the distance between right atrium and the sternal angle is about 10 cm. So, the jugular venous pressure would be estimated at about 14 cm of water, which was rather elevated, and was consistent with his symptoms. In Case 2, the top of jugular venous pulsation in mid-neck area in sitting position was 7–8 cm from the sternal angle. Adding 10 cm (the distance between right atrium and sternal angle in sitting position) to this, her jugular venous pressure was about 17–18 cm water (Figure 1).

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in Heart Failure

After a clinical diagnosis has been established, an echocardiogram should be ordered to determine left ventricular ejection fraction. This is the single most important test for a HF patient. It is important because it assists in guiding medical management and provides prognostic information about HF patients. Generally speaking, patients with low ejection fraction, as in Case 1, have poorer prognosis than those with normal ejection fraction, such as Case 2.17 However, the good news is that the prognosis in HF patients with low ejection fraction can be improved with neurohormonal antagonists, such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, use of which is considered a marker of good quality of care. For most HF patients in the long-term care setting, ejection fraction will likely already be known, as was the case with our Case 1 and Case 2. If this information is not available, an echocardiogram should be ordered, unless contraindicated by patient and family preferences, and life expectancy of the patients. However, with increasing use of mobile echocardiography services, left ventricular ejection fraction should be obtainable for most HF patients in the long-term care settings.

Treatment of Heart Failure in Long-Term Care Setting

Treatment of HF in the long-term care settings can be divided into symptom-relieving and life-prolonging therapies. As symptoms of HF are similar regardless of ejection fraction, symptom-relieving therapies are very similar for both systolic and diastolic HF. However, life-prolonging therapies are generally indicated for systolic HF patients.

ACE inhibitors

All systolic HF patients, whether or not they are symptomatic, should be treated with an ACE inhibitor. If they are intolerant of ACE inhibitors, an angiotensin receptor blocker is an alternative. Cough is the most common reason for intolerance of ACE-inhibitors and can less commonly occur with angiotensin receptor blockers. Case 1 was not receiving an ACE inhibitor and unless he has a history of prior allergic reaction, he should be offered these drugs. However, a common reason for underuse of ACE inhibitors in HF patients is kidney function.5, 18, 19 Generally a rise in serum creatinine is small and transient and should not be a reason for non-initiation or discontinuation of an ACE inhibitor. HF patients with kidney disease have poor prognosis, and evidence suggest that these patients are equally likely to benefit from these drugs. Although the beneficial effect of these drugs has not been proven in patients with diastolic HF, they may provide reno-protection for diastolic HF patients with chronic kidney disease. Data from younger HF patients suggest that the effect of kidney disease may be worse in diastolic than in systolic HF.20 If our Case 2 had not been receiving an ACE inhibitor, it could be considered given her kidney disease. Hyperkalemia is not uncommon in elderly HF patients and ACE inhibitors may be partly responsible. However, before stopping ACE inhibitors, one should look for other sources of potassium including potassium supplements. Serum potassium levels can be kept within normal range by once or twice weekly use of small doses of cation-exchange resins such as kayexalate. This may allow continuation of ACE inhibitors; however, the long-term effect of this approach is not known.

Beta-Blockers

All systolic HF patients should also be prescribed a beta-adrenergic blocker approved for HF unless contraindicated. Metoprolol extended release is a beta-1 selective blocker with little effect on blood pressure and may be more suitable for frail elderly patients with low blood pressure.21, 22 Carvedilol, on the other hand, may be more suitable for those with concomitant high blood pressure. There is no need to wait to maximize the dose of ACE inhibitors before a beta-blocker is initiated. Regular metoprolol tartrate may not be as effective as metoprolol extended release and should not be used in systolic HF.23 Case 1 was receiving metoprolol tartrate, which should be switched to extended release metoprolol succinate and titrated upward as tolerated. Extended release metoprolol succinate can be broken into half but should not be crushed. For patients who need their medication crushed, carvedilol may be used. If carvedilol cannot be used due to low blood pressure, and extended release metoprolol succinate must be crushed, it should be given twice a day. Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers may increase the risk of cardiac bradyarrhythmias and should be avoided. However, more importantly, given the low ejection fraction of Case 1, his verapamil should be discontinued for its potential negative inotropic effects. Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers such as amlodipine or felodipine may be safely used if needed for better blood pressure control in systolic HF.24 However, if his blood pressure is not well controlled, his extended release metoprolol should be switched to carvedilol, which is a better anti-hypertensive drug than metoprolol. This may obviate the need for another anti-hypertensive drug, an important consideration in patients already receiving many drugs. Case 2 was not receiving any beta-blocker. However, given her high blood pressure and relatively high pulse rate, a beta-blocker, preferably one with better anti-hypertensive properties, such as carvedilol or the newly approved beta-blocker nebivolol may be a better choice and may later allow discontinuation of her amlodipine. For patients showing signs of orthostasis, a sitting blood pressure, instead of a supine blood pressure, should be used to guide anti-hypertensive therapy.

Aldosterone Antagonists

Spironolactone may be cautiously used in advanced and symptomatic systolic HF patients. Elderly HF patients with declining kidney function who are also using ACE inhibitors are particularly at risk of hyperkalemia from spironolactone. This drug should also be avoided in patients with kidney disease and high serum potassium, and serum creatinine and potassium should be monitored closely in other patients.25

Diuretics

Most HF patients, regardless of ejection fraction, need diuretics to achieve and maintain euvolemia. While it is known that diuretics activate neurohormonal pathways that can have adverse consequences,26 for symptom control related to volume overload, diuretics are essential.9 Many elderly HF patients do not receive adequate dosages of diuretics needed to achieve euvolemia. Both Case 1 and Case 2 were receiving inadequate dosages of diuretics. This was apparent from their symptoms and signs of fluid volume overload. In addition, diuretics are generally less effective in the presence of kidney disease and larger doses are needed. Based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease or MDRD formula, both case 1 and 2 had chronic kidney disease with estimated glomerular filtration rates for of 39 and 47 ml/min/1.73m2 respectively for Case 1 and Case 2.27 The effectiveness of diuretics can also be assessed by asking patients if they have increased frequency after taking diuretics and by monitoring daily weight. Due to practical logistical difficulties with daily weight in the long-term care setting, it should be restricted to residents with unstable HF and frequent hospitalizations. Once euvolemia is achieved, the lowest possible dose of diuretic should be used to maintain euvolemia and avoid complications such as electrolyte imbalances, dehydration, hypovolemia, hypoperfusion, orthostasis, and potential falls. The use of diuretics should be combined with patient education to adhere to a low-salt diet and fluid restriction of <2 liter per 24 hours. This should generally not be an issue as residents in the long-term care may be more prone to dehydration than volume overload. Torsemide is a less potent activator of aldosterone than furosemide, and less likely to cause hypokalemia.28 However, despite being a generic drug, it is expensive. The long-term effect of neither diuretic has been tested in large randomized clinical trials.

Digitalis

All systolic and diastolic HF patients in the long-term care setting, who are symptomatic despite therapy with the above drugs, should be prescribed digoxin in low doses. Digoxin is known to reduce symptoms and hospitalizations in all HF patients regardless of ejection fraction.29, 30 However, in low doses (≤0.125 mg/day) digoxin is more likely to result in low serum digoxin concentrations (<10 ng/ml), which has been shown to reduce mortality.29, 31 HF patients who cannot tolerate beta-blockers should be given digoxin as it has been shown to reduce mortality in low doses in patients already receiving an ACE inhibitor.29 For most HF patients in the long-term care setting a starting dose of ≤0.125 mg/day will suffice. However, in patients with advanced age and in those with kidney disease, such as our Case 1 and Case 2, digoxin should be prescribed as 0.0625 mg daily or 0.125 mg every other day. The dose of digoxin should be appropriately reduced in our Case 2 and if there is any clinical evidence of digoxin toxicity, her serum digoxin level should be checked. If prescribed in low doses, the risk of digoxin toxicity is low and there is no need for routine or frequent serum digoxin monitoring. However, serum digoxin levels should be checked if clinical digoxin toxicity is suspected and before increasing the dose of digoxin for patients who remain symptomatic despite the initial low dosages.

Management of Complications

Hypokalemia is common in HF, in part due to neurohormonal activation, and also caused by diuretics. Serum potassium levels < 4 mEq/L, have been associated with increased morbidity.32 Therefore, potassium levels should be maintained to at least ≥4 mEq/L and preferably to around 4.5 mEq/L. Oral potassium supplements are generally effective in achieving normokalemia. However, spironolactone may be preferable over potassium supplement for maintenance of normokalemia.33 Potassium supplements are not effective in correcting other electrolyte imbalances such as hypomagnesemia, commonly associated with hypokalemia. Case 1 should be prescribed oral potassium supplement to achieve normokalemia. Oral potassium in Case 2 may be replaced with spironolactone 12.5 or 25 mg daily, which will not only likely correct her potassium balance but also suppress aldosterone which is being activated both by her HF failure and her diuretic therapy. Aldosterone is a key neurohormone in HF that is associated with myocardial fibrosis, disease progression and poor prognosis.25

Management of Comorbidities

Common cardiovascular comorbidities such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, hypercholesterolemia, chronic kidney disease, peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease and atrial fibrillation should be adequately treated.34 Treatment of non-cardiovascular comorbidities is also important. Depression is common in the elderly and may present atypically.35 Depression is associated with poor outcomes including increased risk of placement in the long-term care settings.35 Poor physical activity may be a negative prognostic marker in HF.36 Pain from osteoarthritis or other causes should be optimally treated to allow optimal physical activity.

Conclusions

HF in the long-term care setting is a complex syndrome, the management of which can be challenging. However, following a simple 5-step protocol called “DEFEAT-HF” one can organize the process: Starting with a clinical Diagnosis and establishing an Etiology, one should assess Fluid volume and achieve euvolemia and determine Ejection frAction to guide Therapy. Guidelines provide little specific information for HF patients in the long-term care setting. However, familiarity with a major national guideline may provide a foundation on which HF treatment in the long-term care setting can be individualized.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Ahmed is supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5-R01-HL085561-02 and P50-HL077100), and a generous gift from Ms. Jean B. Morris of Birmingham, Alabama.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ali Ahmed, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, and Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, and Director, Geriatric Heart Failure Clinics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Birmingham, Alabama.

Linda Jones, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care, Department of Medicine School of Medicine, Instructor, School of Nursing, and Nurse Practitioner, Geriatric Heart Failure Clinic, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama.

Clare I. Hays, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care, Department of Medicine School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham and Medical Director, Fairhaven Retirement Center, Birmingham, Alabama.

References

- 1.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007 Feb 6;115:e69–e171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed A, Sims RV. Highlights of the national nursing home survey: 1995. Annals of Long-Term Care. 2000;6:62–67. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed A. Clinical characteristics of nursing home residents hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2002 Sep–Oct;3:310–313. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000019535.50292.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronow WS. Mortality in nursing home patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003 Jul–Aug;4:220–221. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000073962.72130.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed A, Weaver MT, Allman RM, DeLong JF, Aronow WS. Quality of care of nursing home residents hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002 Nov;50:1831–1836. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson J, Beier M, Cohn E, et al. Heart Failure; Clinical Practice Guideline. Columbia, MD, USA: American Medical Directors Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed A. DEFEAT heart failure: clinical manifestations, diagnostic assessment, and etiology of geriatric heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2007 Oct;3:389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed A. Treatment of chronic heart failure in long-term care facilities: implications of recent heart failure guidelines recommendations. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003 Sep–Oct;37:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(03)00027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005 Sep 20;112:e154–e235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed A, Allman RM, Aronow WS, DeLong JF. Diagnosis of heart failure in older adults: predictive value of dyspnea at rest. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004 May–Jun;38:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottdiener JS, Arnold AM, Aurigemma GP, et al. Predictors of congestive heart failure in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 May;35:1628–1637. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JP, Selter JG, Wang Y, et al. The obesity paradox: body mass index and outcomes in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Jan 10;165:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drazner MH, Rame JE, Stevenson LW, Dries DL. Prognostic importance of elevated jugular venous pressure and a third heart sound in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 23;345:574–581. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mueller C, Scholer A, Laule-Kilian K, et al. Use of B-type natriuretic peptide in the evaluation and management of acute dyspnea. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 12;350:647–654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinayak AG, Levitt J, Gehlbach B, Pohlman AS, Hall JB, Kress JP. Usefulness of the external jugular vein examination in detecting abnormal central venous pressure in critically ill patients. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 23;166:2132–2137. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seth R, Magner P, Matzinger F, van Walraven C. How far is the sternal angle from the mid-right atrium? J Gen Intern Med. 2002 Nov;17:852–856. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed A. Association of diastolic dysfunction and outcomes in ambulatory older adults with chronic heart failure. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005 Oct;60:1339–1344. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.10.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed A. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with heart failure and renal insufficiency: how concerned should we be by the rise in serum creatinine? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002 Jul;50:1297–1300. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed A, Kiefe CI, Allman RM, Sims RV, DeLong JF. Survival benefits of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in older heart failure patients with perceived contraindications. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002 Oct;50:1659–1666. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Sanders PW, et al. Chronic kidney disease associated mortality in diastolic versus systolic heart failure: a propensity matched study. Am J Cardiol. 2007 Feb 1;99:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed A, Dell'Italia LJ. Use of beta-blockers in older adults with chronic heart failure. Am J Med Sci. 2004 Aug;328:100–111. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200408000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed A. Myocardial beta-1 adrenoceptor down-regulation in aging and heart failure: implications for beta-blocker use in older adults with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003 Dec;5:709–715. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole-Wilson PA, Swedberg K, Cleland JG, et al. Comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol on clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure in the Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003 Jul 5;362:7–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13800-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziesmer V, Ghosh S, Aronow WS. Use of antihypertensive drug therapy in older persons in an academic nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003 Mar–Apr;4:S20–S22. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000019728.19341.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999 Sep 2;341:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed A, Young JB, Love TE, Levesque R, Pitt B. A propensity-matched study of the effects of chronic diuretic therapy on mortality and hospitalization in older adults with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2007 Aug 14; doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Mar 16;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cosin J, Diez J. Torasemide in chronic heart failure: results of the TORIC study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002 Aug;4:507–513. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed A. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in geriatric heart failure: importance of low doses and low serum concentrations. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007 Mar;62:323–329. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, et al. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006 Aug 1;114:397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed A, Pitt B, Rahimtoola SH, et al. Effects of digoxin at low serum concentrations on mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a propensity-matched study of the DIG trial. Int J Cardiol. 2008 Jan 11;123:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed A, Zannad F, Love TE, et al. A propensity-matched study of the association of low serum potassium levels and mortality in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2007 Jun;28:1334–1343. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed A, Adamopoulos C, Sui X, Love TE. Potassium supplement use may increase hospitalization without affecting mortality in chronic heart failure: Implications for use of aldosterone antagonists to maintain potassium balance in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:II–766. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aronow WS, Ahn C, Gutstein H. Prevalence and incidence of cardiovascular disease in 1160 older men and 2464 older women in a long-term health care facility. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002 Jan;57:M45–M46. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.1.m45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmed A, Ali M, Lefante CM, Mullick MS, Kinney FC. Geriatric heart failure, depression, and nursing home admission: an observational study using propensity score analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006 Oct;14:867–875. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000209639.30899.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed A, Aronow WS. A propensity-matched study of the association of physical function and outcomes in geriatric heart failure. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007 May 24; doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]