Abstract

Emotional disclosure by writing or talking about stressful life experiences improves health status in non-clinical populations, but its success in clinical populations, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (RA), has been mixed. In this randomized, controlled trial, we attempted to increase the efficacy of emotional disclosure by having a trained clinician help patients emotionally disclose and process stressful experiences. We randomized 98 adults with RA to one of four conditions: a) private verbal emotional disclosure; b) clinician-assisted verbal emotional disclosure; c) arthritis information control (all of which engaged in four, 30-minute laboratory sessions); or d) no-treatment, standard care only control group. Outcome measures (pain, disability, affect, stress) were assessed at baseline, 2 months following treatment (2-month follow-up), and at 5-month, and 15-month follow-ups. A manipulation check demonstrated that, as expected, both types of emotional disclosure led to immediate (post-session) increases in negative affect compared with arthritis information. Outcome analyses at all three follow-ups revealed no clear pattern of effects for either clinician-assisted or private emotional disclosure compared with the two control groups. There were some benefits in terms of a reduction in pain behavior with private disclosure versus clinician-assisted disclosure at the 2 month follow-up, but no other significant between group differences. We conclude that verbal emotional disclosure about stressful experiences, whether conducted privately or assisted by a clinician, has little or no benefit for people with RA.

Introduction

Studies suggest that written or verbal emotional disclosure about stressful events by writing or talking leads to temporary increases in negative affect, followed by improved health during subsequent months, at least with healthy populations (Smyth 1998). Recent studies have tested this technique in clinical samples, but with weaker results (Frisina et al., 2004). Emotional disclosure may help people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) because they experience elevated stress (Koehler, 1985; Rimon & Laakso, 1985), are reactive to stress (Thomason et al., 1992; Zautra et al., 1994; Potter & Zautra, 1997) and tend to inhibit expressing negative emotions (Fernandez et al., 1989). To date, four published randomized trials have tested disclosure in RA, with mixed results. Smyth et al. (1999) found that RA patients who wrote about stress for 3 days in the laboratory had better physician ratings of disease 4 months later than patients engaged in neutral writing. Kelley et al. (1997) demonstrated that RA patients randomized to talk about stress into a tape recorder at home for 4 days had better self-reported affective and physical functioning—but not pain or joint condition—3 months later than did controls. Wetherell et al. (2005) found that RA patients who disclosed at home (either writing or speaking) had better mood and less disease activity than controls 10 weeks later, but these effects were due to unexpected worsening among controls, rather than improvements among the disclosure group. Finally, Broderick et al. (2004) found that 3 days of at-home written disclosure writing had no effects at 6-month follow-up, although an enhanced disclosure condition showed equivocal benefits, confounded by pre-treatment group differences.

Research is needed on methods to enhance disclosure’s effects. Studies suggest that participants may benefit from instructions that help them identify and express feelings (Sloan et al. 2007), remain on topic over disclosure days (Sloan et al. 2005), make a coherent narrative (Smyth et al. 2001) and explore the meaning of the experience (Pennebaker et al. 1997; Gidron et al. 2002; Ullrich & Lutgendorf 2002; Broderick et al. 2004). Studies of emotional disclosure via the internet using individualized therapist feedback have shown substantial effects (Lange et al., 2001; 2003), and disclosure to a therapist appears to create as much improvements as private disclosure, but with less negative affect (Murray et al. 1989; Donnelly & Murray 1991; Segal & Murray 1994; Anderson et al. 2004).

We hypothesized that clinician assistance would increase the benefits of disclosure because a clinician can help patients identify and verbalize their feelings, remain on topic, and reflect on the meaning of their experience. We compared clinician-assisted disclosure to private verbal disclosure and a neutral arthritis information control condition and a standard care group. We tested verbal rather than written disclosure because verbal disclosure can be effective for RA (Kelley et al., 1997) and disclosure to and assistance by a clinician is typically verbal. We tested not only immediate mood effects of disclosure but also effects at 15 month follow-up, which is much longer than prior studies of disclosure in RA.

Methods

Subjects

Patients with RA were recruited from clinics affiliated with the Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine or Duke University Medical School. Recruitment occurred between May of 2000 and December of 2003. All patients were given a history and physical examination by one of the study rheumatologists and included only if they met 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for the diagnosis of RA. Patients were excluded if they had other organic disease that would significantly affect function (e.g., COPD) or rheumatic disorders other than RA. Patients with severe personality disorders (e.g., borderline personality disorder), substance abuse problems, or who were involved in current psychiatric treatment were excluded.

Procedure

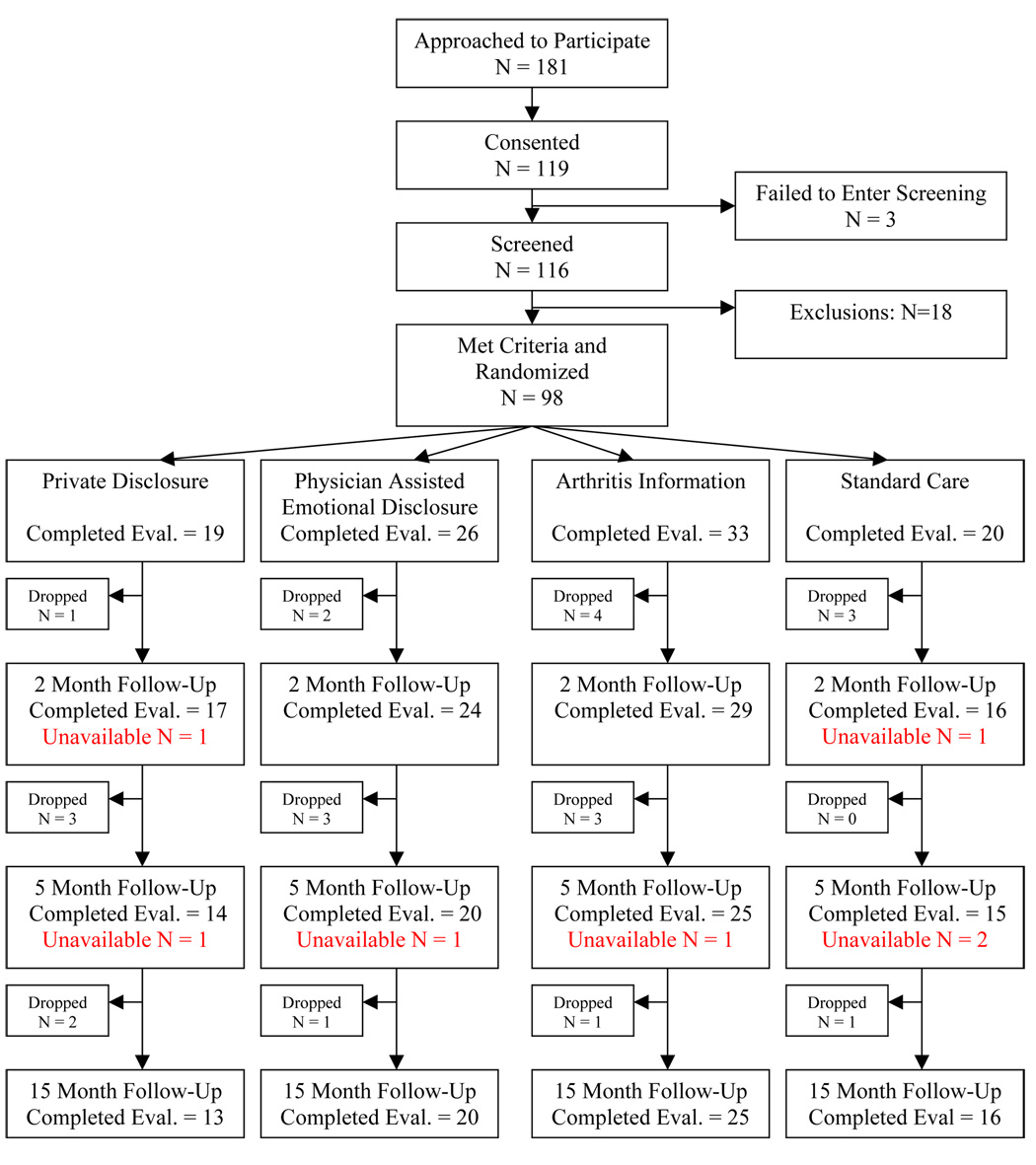

After providing consent, patients were screened to determine if they met eligibility criteria. They next completed a baseline assessment to assess pain, physical disability, psychological disability, stress, and affect and then were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: a) private emotional disclosure, b) clinician-assisted emotional-disclosure, c) arthritis information, or d) standard care. Randomization was done by concealment with assignments in sealed envelopes and investigators and patients unaware of treatment condition until the date of randomization. All patients, except those in the standard care condition, attended four, 30-min sessions within a 3 week time interval in the research clinic (mean number of days from start to completion of treatment=21.3 days). All treatment sessions were audiotaped and participants were instructed that audiotapes would be listened to by members of the research study staff. To ensure confidentiality, session audiotapes were marked with an identification number rather than participants' names. Participants in the three intervention groups rated their negative affect before and after each session. Follow-up assessments were conducted 2 months after the end of the treatment period (2-month follow-up) and 5, and 15 months after the treatment period. Figure 1 is a CONSORT diagram that provides an overview of the study design and information on numbers of patients evaluated at each time point.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Participants through the Study.

Intervention Conditions

Private emotional disclosure

Participants in this condition spent 30 minutes during each of four sessions, alone in a private room in the clinic, talking into an audiotape recorder. Instructions were similar to those used in standard disclosure studies (Pennebaker 1995), but modified for a verbal, tape-recorded format as done by Kelley et al. (1997). Participants were instructed to identify an unresolved stressful experience in their lives, and they were given cues to facilitate this (e.g., an experience that is uncomfortable to talk about or remember, that makes one feel anxious or upset, that is avoided when possible, or that crosses the mind frequently). They were instructed to talk about this experience, including both the facts and their deepest feelings about it and to label their feelings. They also were instructed that they could explore how the experience is related to how they are dealing with rheumatoid arthritis, and they could discuss how the experience relates to their childhood, family, parents, children, and friends. They were encouraged to “work on and resolve one stressful experience at a time, even if it means talking about the same experience over several days. However, if you find that you have worked it out or feel better about it, you should go on and talk about another stressful topic.”

Clinician-assisted emotional disclosure

The clinician-assisted emotional disclosure protocol was designed to retain the structural and practical advantages of a standard 4-session private disclosure protocol, but to enhance the patient’s experience through the use of emotional focusing techniques in the form of a brief, nurse-administered protocol. This protocol was developed for this study by integrating the findings of studies that suggest the benefits of emotional exploration, narrative structure, and meaning development (Smyth et al. 2001; Gidron et al. 2002; Broderick et al. 2004; Sloan et al. 2005; Sloan et al. 2007) with specific techniques taken from Emotion-Focused Therapy (Greenberg et al., 1993). Participants in this condition met with a nurse for four, 30-minute individual sessions and were provided the same instructions as the private disclosure group. The nurse was trained to create and maintain a relationship by using techniques of active listening, reflection, and avoiding negative judgments to help the patient feel a sense of positive regard and acceptance. Against this backdrop of a positive relationship, the nurse used two techniques to facilitate emotional disclosure: a) discovering and elaborating feelings, and b) emotional focusing. The first component involves assisting the patient to identify problematic or stressful experiences, discuss the experiences surrounding the problematic event and to search for relevant internal and external details, to track the personal meanings that they assign to the causes of the event and their own reactions, and to engage in a broader re-examination of the event. Emotional focusing is embedded within the process of discovering and elaborating narratives. The technique of experiential focusing (Greenberg, et al, 1993) encouraged patients to try to focus solely on feelings about the problem event while avoiding thinking about interfering thoughts. Patients were helped to identify as many different aspects of the emotional experience as possible and develop verbal labels to describe their experience.

Arthritis information control condition

Participants in this control condition met with a nurse for four, 30-minute individual sessions and were provided basic information about rheumatoid arthritis. The arthritis information sessions used a lecture-discussion format based on the early work of Lorig (1982) and sessions were supplemented by charts and photographs. The protocol provided information about the nature of rheumatoid arthritis disease, treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, exercise, and methods for joint protection and maintaining mobility and function. This condition was designed to serve as a control for time, attention, and interaction with a nurse.

Standard Care Control Condition

The standard care condition was designed to serve as a routine treatment control. These patients did not attend individual sessions for emotional disclosure or arthritis information, but they did complete all measures at time intervals corresponding to the baseline and the three follow-up assessments. This condition served as a control for the passage of time.

Nurse Training

Treatment sessions for the clinician-assisted emotional disclosure and arthritis information sessions were conducted by registered nurses each of whom had over 20 years of experience in patient education and psychosocial interventions. To control for nurse effects, the same nurses conducted both the clinician-assisted disclosure and the arthritis information sessions. Nurses were taught the clinician-assisted emotional disclosure protocol and arthritis information protocol in a 4-day didactic and experiential course (2 days each). For clinician-assisted emotional disclosure, nurses were provided with a written protocol that was reviewed during didactic sessions. During these didactic sessions, transcripts of treatment sessions were used to illustrate training issues (e.g., identifying generic narratives and ways to “unfold” the story by encouraging the narrator to identifying emotional “markers”). Videotapes of model cases were also used to illustrate key points. Nurses then role-played common scenarios that could arise in treatment. After the training seminar, each nurse was assigned two practice cases (normal volunteers) in which they utilized the 4-session protocol. Training in the arthritis information protocol was similar in that nurses practiced common scenarios likely to arise in the sessions. They also practiced the protocol with two practice cases (normal volunteers). All of the actual clinician-assisted emotional disclosure sessions and arthritis information sessions were audio-taped, and tapes were reviewed in weekly supervision sessions with a supervisor in which feedback on adherence to the protocol was provided.

Measures

Immediate affect reactions to sessions

Patients in the three active conditions completed the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) immediately before and after each session. Items were rated on a 1 – 5 scale and summed. We scored the 10-item negative affect (NA) scale and analyzed change scores (post-session minus pre-session). Internal consistency of NA for this sample was examined using Cronbach's alpha and found to be high (α = 0.929).

Outcome Measures

We assessed pain, physical disability, psychological disability, pain behavior, stress, and affect (positive and negative) at baseline as well as at 1-, 3-, and 12-month follow-ups. We included measures of physical disability, psychological disability, and affect because prior studies of emotional disclosure in RA patients had shown that disclosure can produce significant improvements in one or more of these outcomes (Smyth, et al., 1999; Kelley, et al. 1997; Wetherell et al., 2005; Broderick, et al., 2004). We included measures of pain, pain behavior, and stress because we believed that clinician-assisted emotional disclosure might enhance the effects of prior disclosure enough to produce improvements in these important RA outcomes.

Outcome measures of pain, physical disability, and psychological disability

The Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale (AIMS; Meenan et al., 1982; Meenan et al., 1991) was used to measure pain, physical disability and psychological disability over the past month. Internal consistency of each of the AIMS measures was found to be high (pain: α= 0.824; physical disability: α= 0.807; psychological disability: α= 0.925). Research has supported the reliability of the AIMS and found it is valid when used with different types of arthritis, with a range of social and demographic groupings, and in different clinical settings (Meenan et al., 1982).

Daily Stress

Levels of perceived stress were assessed using the Daily Stress Inventory (DSI, Brantley et al., 1987). The DSI is a 58-item self-report measure that yields measures of both the frequency of stressors and severity of stressors over the past day. Prior research has indicated that the DSI has good test-retest reliability. Over a 28 consecutive day period the test-retest reliability for the frequency of stressors was 0.72 (Brantley et al, 1987). Research indicates that the DSI has good validity when used with patients having RA in that the DSI frequency of stressors is very highly correlated with the DSI severity of stressors measure (Parker et al., 1995). Thus, for this study, the frequency of stressors was used as the outcome variable.

Positive and negative affect

The PANAS was used to assess affect and both positive affect (PA) and NA scores were calculated. Internal consistency for both scales was found to be high (α = 0.917 for positive affect and α = 0.899 for negative affect.).

Pain behavior measure

Pain behavior was recorded using an RA version (McDaniel, Anderson, Bradley, et al., 1986) of an observation method developed in our lab (Keefe & Block, 1982) which consists of a 10-minute session in which the patient engages in a standard, timed set of activities: sitting, walking, standing and reclining. Trained observers recorded the occurrence of 7 categories of behavior (guarding, bracing, grimacing, sighing, rigidity, passive rubbing, and active rubbing). Two observers independently coded 32% of the pain behavior samples and the inter-observer reliability was 85% (percentage agreement). A composite score, total pain behavior, was calculated based on the frequency of each pain behavior. Previous research has supported the reliability and validity of the total pain behavior measure (McDaniel, et al. 1986; Anderson, Bradley, McDaniel, et al. 1987;Anderson, Keefe, Bradley, et al., 1988).

Content Coding of Disclosure Sessions. For both the private disclosure and clinician assisted disclosure conditions, each of the events discussed in the session was content coded. Events were coded in the following categories: (a) RA experience; (b) non-RA physical problems; (c) interpersonal conflict; (d) general life stressors and trauma; (e) loss through death. The categories were not mutually exclusive. Prior to content coding, two coders who were not involved in the content coding, followed Angus, Levitt, and Hardtke’s (1999) method for identifying shifts in narrative structure, referred to as sequences. Sessions had a mean of 17.6. (SD = 6.3) sequences, which ranged from 2 to 40 sequences per session. Each content category was calculated as a percentage of sequences in which the event content had been identified within the session.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Ninety-eight participants (73.5% women; 90.8% Caucasian) were randomized into the study. On average, the participants were 56 years old (SD = 10.59) and reported having had rheumatoid arthritis for 14 years. In terms of education level, 29% had a high school degree or less, 28% had some college education, 21% had completed college, and 21% had some professional or graduate training. Twenty-seven participants were assigned to the clinician-assisted emotional disclosure intervention, 18 were assigned to the private emotional disclosure intervention, 33 were assigned to the arthritis education condition, and 20 were assigned to the usual care control condition. Data analyses revealed that the four groups did not differ significantly at baseline by age, race, sex, or education level.

Because not all of the participants completed the study, we compared the demographic information of patients completing measures at all four evaluation periods to demographic information of patients who withdrew from the study at any time-point following randomization. A series of t-tests and chi-square tests of independence found no statistically significant differences on age, sex, race, education, disease duration, or any of the baseline measures between participants who completed the study and those who withdrew from the study. In addition, no statistically significant differences in study withdrawal rates were found among the four randomization conditions.

Finally, we compared primary outcome analyses based on available participant data with outcome analyses based on imputed data for participant dropouts (last-value-carried forward method). No differences emerged between these two sets of analyses. Therefore, the following analyses were based on available participant data at each time point and do not include imputed values for participant dropouts.

Manipulation Check: Effects on Immediate Mood

In order to verify that emotional disclosure was implemented effectively, we compared negative affect ratings before and after each of the four sessions for the three groups that had live sessions (i.e., private disclosure, clinician-assisted disclosure, and arthritis information control). We expected the two disclosure conditions to demonstrate within session increases in negative affect ratings, which also would be greater than those found for the arthritis information condition. Analyses on pre-session PANAS negative affect ratings (gathered prior to session 1) revealed no pre-treatment differences among the three groups, F(2,66) = .76, p=.47. A day (4) × treatment condition (3) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) on post- minus pre-session negative affect change scores indicated a significant condition main effect, F(2,55) = 6.18, p <.01, partial η2 = .18, but not day or condition by day effects. Follow-up analyses revealed that those in the private disclosure condition reported significantly greater within-session increases in negative affect than those in the arthritis education condition (p = .004). Those in the clinician-assisted disclosure condition tended to have greater within-session increases in negative affect than those in the arthritis education condition (p = .15). Based on these analyses, the manipulation of the emotional disclosure factor was done successfully.

Content analyses

Repeated measures analyses were used to determine whether there were significant changes in the content discussed over the course of the four sessions, and whether or not this varied as a function of treatment group. Changes across the sessions did not differ by treatment group (private versus clinician-assisted disclosure) on the proportion of sessions devoted to discussing RA experience, F=2.08, p>05, nor were there Session X Treatment group interactions for the other content categories.

However, there were within-subject changes in the proportion of sessions devoted to discussing RA Experience, F= 4.89, p<.01. Discussion of RA experiences was relatively high in the first sessions, with the mean percentage of segments discussing this topic being M=24.9, SD=29.7. In the second session this mean percentage dropped to M=14.3, SD=19.9, and even further in the third session to M=10.9, SD=14.2. In the fourth session this mean percentage rose again to M=20.1, SD=27.6. Simple contrasts analyses indicated that the largest significant difference for amount of RA discussion was between sessions one and three F= 7.65, p<.05. Also significantly different from each other for RA discussion were sessions three and four F= 5.20, p<.05, and there was a trend toward significant difference found between sessions one and two F=3.06, p<.10.

There were no other significant changes in the proportion of sessions devoted to discussing the other content categories. Because the remaining content categories were not different between treatment groups or across the 4 sessions, means and standard deviations for the other content codes are presented as an aggregate of the 4 sessions in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Content Coding

| Description of Content | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Experience with rheumatoid arthritis | 16.5 | 15.7 |

| Physical problems other than RA | 4.2 | 5.2 |

| Death of a friend or loved one | 9.5 | 12.7 |

| Experience or witness or traumatic event | 7.5 | 14.6 |

| Interpersonal problems | 34.9 | 25.9 |

| Other life stressors | 13.3 | 13.6 |

Analysis of Pre-Treatment Group Differences

A series of analyses of variance (ANOVAs) was conducted to test for pre-treatment differences in the outcome measures among the four treatment conditions. Only one difference, on baseline positive affect, was found, F(3,90) = 3.29, p < .05. Participants randomized to usual care reported greater positive affect (M = 2.80, SD = 0.89) than participants randomized to clinician-assisted emotional disclosure (M = 2.02, SD = 0.84). None of the other outcome measures differed among groups at baseline. In addition, t-tests were conducted to examine pre-treatment differences between the testing sites. Compared to the Duke University Medical Center site, patients at the Ohio University site had significantly higher pre-treatment scores on daily stress, (MOU = 56.47 vs. MDUMC = 35.20, p < .05) and pre-treatment observed pain behaviors, (MOU = 16.97 vs. MDUMC = 8.36, p < .001), but significantly lower scores on pretreatment positive affect (MOU = 2.12 vs. MDUMC = 2.56 vs. p < .001). To control for site differences, location was included as a covariate in all subsequent outcome analyses. There were no differences in age, race, sex, or education level between participants who completed the study and those who withdrew from the study. Also, the four treatment groups did not differ significantly in terms of dropout rates.

Outcome Analyses

Outcome analyses were conducted both using an intent-to-treat model (using last value carried forth) and a model that used the number of available participants at each evaluation. No differences in results were obtained between these two sets of analyses. Therefore, the following analyses were based on available participant data at each evaluation. Outcome analyses examined differences among the four treatment groups on each outcome measure at each of the three follow-up evaluation points (2-month, 5-month, and 15-month). Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted, in which study site (Duke vs Ohio University) and pre-treatment values of outcome measures were entered as covariates. Estimates of effect size were computed using the partial η2 statistic, which estimates the proportion of variance in the outcome related to the treatment factor while holding constant pre-treatment scores. Although cutoffs for small, medium, and large values of partial η2 have not been determined, conventional effect size estimates of .01, .06, and .14 are considered to be small, medium, and large, respectively (Green et al., 2000).

Analysis of Group Differences in Outcome Measures at 2-Month Follow-up

Table 2 presents the unadjusted means and standard deviations for the study outcome measures at each evaluation period. The results of an ANCOVA revealed a significant difference in observed pain behaviors according to condition, F(1,75) = 2.72, p= .05, partial η2 = .11. Following treatment, those in the private disclosure group exhibited significantly fewer pain behaviors than those in the clinician-assisted group (MPD = 7.14 vs. MCAD = 13.23, p < .05). The level of pain behaviors in the private disclosure group did not differ significantly from pain behaviors in the standard care (MSC = 11.80) or arthritis education (MAE = 11.82) groups. Additional analyses found no significant between group differences in 2-month follow-up measures of pain, F(3,82)=1.44, ns, partial η2 =.05, physical disability, F(3,82)=0.29, ns, partial η2 <.01, psychological disability, F(3,82)=0.61, ns, partial η2 =.02, daily stress, F(3,82)=1.08, ns, partial η2 = .04, positive affect, F(3,79)=1.38, ns, partial η2 = .05, and negative affect F(3,80)=2.20, ns, partial η2 = .08.

Table 2.

Unadjusted outcomes by treatment condition for the baseline and follow-up evaluations

| Measures | Private Disclosure | Clinician-Assisted Disclosure | Arthritis Information | Standard Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| AIMS Pain | ||||

| Baseline | 4.68 (2.52) | 4.75 (2.36) | 5.06 (2.07) | 4.28 (1.41) |

| 2-Month Follow | 5.15 (2.66) | 4.54 (2.28) | 4.90 (1.87) | 4.93 (1.69) |

| 5-Month Follow | 4.71 (2.78) | 4.43 (2.23) | 5.02 (1.91) | 4.27 (2.12) |

| 15-Month Follow | 5.00(2.30) | 4.75 (2.68) | 4.48 (2.18) | 4.22 (1.92) |

| AIMS Physical | ||||

| Baseline | 2.01 (1.16) | 2.30 (1.61) | 1.97 (1.06) | 1.56 (1.08) |

| 2-Month Follow | 1.86 (1.04) | 2.29 (1.55) | 1.92 (0.98) | 1.92 (1.04) |

| 5-Month Follow | 1.72 (0.93) | 2.36 (1.85) | 1.80 (0.99) | 1.70 (1.05) |

| 15-Month Follow | 1.90 (0.99) | 2.41 (1.75) | 1.72 (0.91) | 1.89 (1.08) |

| AIMS Psychological | ||||

| Baseline | 2.46 (0.96) | 2.58 (1.76) | 2.89 (1.71) | 2.35 (1.68) |

| 2-Month Follow | 2.65 (1.41) | 2.57 (1.62) | 2.97 (1.72) | 2.11 (1.33) |

| 5-Month Follow | 2.53 (1.20) | 2.48 (1.63) | 2.73 (1.43) | 2.39 (2.25) |

| 15-Month Follow | 2.53 (1.33) | 2.88 (1.69) | 2.55 (1.33) | 2.41 (2.02) |

| Positive Affect | ||||

| Baseline | 2.42 (0.86) | 2.02 (0.84) | 2.48 (0.75) | 2.80 (0.89) |

| 2-Month Follow | 2.34 (0.78) | 2.18 (0.84) | 2.19 (0.85) | 2.60 (0.93) |

| 5-Month Follow | 2.62 (0.75) | 2.28 (0.73) | 2.21 (0.89) | 2.50 (0.96) |

| 15-Month Follow | 2.58 (0.44) | 2.14 (0.81) | 2.40 (0.93) | 2.68 (1.03) |

| Negative Affect | ||||

| Baseline | 0.61 (0.45) | 0.71 (0.88) | 0.68 (0.57) | 0.42 (0.55) |

| 2-Month Follow | 0.81 (0.71) | 0.60 (0.75) | 0.48 (0.55) | 0.66 (0.81) |

| 5-Month Follow | 0.86 (0.61) | 0.73 (0.73) | 0.47 (0.38) | 0.44 (0.70) |

| 15-Month Follow | 0.85 (0.86) | 0.56 (0.83) | 0.49 (0.61) | 0.61 (0.72) |

| Daily Stress | ||||

| Baseline | 2.54 (0.71) | 2.64 (0.98) | 2.43 (0.90) | 2.27 (0.89) |

| 2-Month Follow | 2.78 (0.83) | 2.47 (1.22) | 2.58 (1.20) | 2.72 (1.06) |

| 5-Month Follow | 2.38 (0.70) | 2.39 (0.97) | 2.21 (0.96) | 2.39 (1.17) |

| 15-Month Follow | 2.43 (1.22) | 2.36 (1.15) | 1.99 (0.86) | 2.33 (0.86) |

| Pain Behaviors | ||||

| Baseline | 10.89 (7.71) | 11.8 (9.70) | 12.8 (8.70) | 8.37 (7.20) |

| 2-Month Follow | 5.42 (5.60) | 12.5 (10.0) | 12.6 (8.74) | 8.87 (8.17) |

| 5-Month Follow | 7.85 (6.78) | 13.9(12.2) | 12.5 (8.62) | 10.4 (8.45) |

| 15-Month Follow | 12.5 (6.86) | 14.5 (14.0) | 10.3 (9.61) | 11.9 (10.7) |

Analysis of Group Differences in Outcome Measures at 5-Month Follow-up

The results of ANCOVAs found no significant group differences on 5-month follow-up measures of pain, F(3,71)=.36, ns, partial η2 = .02, physical disability, F(3,68)=1.37, ns, partial η2 = .06, psychological disability, F(3,70)=0.50, ns, partial η2 < .02, daily stress, F(3,72)=0.37, ns, partial η2 = .02, positive affect, F(3,69)=2.06, ns, partial η2 = .09, negative affect, F(3,70)=1.40, ns, partial η2 = .06, or pain behaviors, F(3,68)=1.09, ns, partial η2 = .05.

Analysis of Group Differences in Outcome Measures at 15-Month Follow-up

The results of ANCOVAs conducted on the outcome measures collected at 15 month follow-up revealed no significant between group differences in pain, F(3,72)=1.16, ns, partial η2 = .05, physical disability, F(3,67)=0.43, ns, partial η2 = .02, psychological disability, F(3,71)=0.20, ns, partial η2 = .01, daily stress, F(3,71)=1.38, ns, partial η2 = .06, positive affect, F(3,70)=0.71, ns, partial η2 = .03, negative affect, F(3,69)=1.41, ns, partial η2 = .06, or pain behaviors, F(3,67)=1.60, ns, partial η2 = .07.

Discussion

This study found that, in RA patients, emotional disclosure either done privately or in the presence of a clinician had very modest effects on treatment outcomes. Disclosure had significant effects on within-session measures of affect and on a measure of pain behavior assessed at 2 month follow-up, but no effects on other outcome measures.

As a manipulation check, we gathered measures of positive and negative affect before and after each disclosure session. One would expect that disclosure will lead to immediate within session increases in negative affect. This study found that the private disclosure manipulation did lead to increases in negative affect suggesting the intervention was implemented in a manner that had immediate effects that were similar to those reported by others. Interestingly, when patients disclosed to a nurse clinician, there was a smaller increase in negative affect, particularly in the first session. This suggests that the presence of a supportive nurse may temper the immediate distressing impact of emotional disclosure, which is consistent with prior studies (Murray et al. 1989; Donnelly and Murray 1991; Segal and Murray 1994; Anderson et al. 2004).

To our knowledge, this is the first study of emotional disclosure that has assessed pain behavior directly. This study found that, when compared to clinician-assisted disclosure, private disclosure produced a reduction in pain behavior at the 2-month follow-up. The fact that changes in pain behavior were found is somewhat interesting because the pain behavior measure used in this study is a directly observed measure of pain and does not rely on self-report. The finding that this measure showed short-term improvement whereas the self-report measure of pain did not is consistent with conclusions of meta-analyses that effects of disclosure tend to be stronger on objective and physical outcomes than on self-reported psychological outcomes (Smyth 1998; Frisina et al. 2004). The findings regarding pain behavior, however, must be interpreted with caution though since they were only observed at the post-treatment evaluation and were observed only for the comparison of private disclosure to clinician assistant disclosure and not to comparisons to the two control conditions.

The current study is one of the first to examine the long-term effects of a brief (4 session) emotional disclosure protocol) on pain and disability in RA patients. At 15-month follow-up, no significant effects were noted. Future studies are needed to further examine the long-term effects of emotional disclosure protocols in patients with RA and other chronically painful diseases.

To date, most studies of emotional disclosure have been carried out in healthy, non-clinical samples. Meta-analyses of this literature suggest that, in these samples, emotional disclosure yields moderate effects (Smyth 1998). Fewer studies have examined the effects of emotional disclosure in clinical samples such as patients suffering from pain due to RA or other diseases, but a recent meta-analysis of studies conducted with clinical samples suggests that emotional disclosure yields variable but on average, small effects (Frisina et al. 2004; Harris 2006). Our findings obtained in RA patients, coupled with those of other studies of disclosure in RA patients (Kelley et al. 1997; Broderick et al. 2004; Wetherell et al. 2005), suggest that emotional disclosure has very modest effects in patients with RA. This might have implications for various interventions that use verbal expression about life events and stress, such as life review, reminiscence, or narrative therapy; these approaches should be tested in well controlled studies to determine whether they are beneficial.

This study had certain strengths and limitations. Unlike several other studies of disclosure in RA, which conducted disclosure at home and found limited or negligible effects (Kelley et al. 1997; Broderick et al. 2004; Wetherell et al. 2005), our disclosure sessions were held under the structured and supervised condition of the laboratory, which may lead to stronger effects, as demonstrated in a laboratory study of disclosure in RA (Smyth et al. 1999). We also included a no-intervention control group to better understand the source of occasional reports of worsening among neutral writing / talking control groups (Wetherell et al. 2005). We included multiple follow-ups over 15 months to understand the time course of any observed effects. Finally, we developed and implemented a clinician-assisted protocol based on empirically-supported techniques from experiential therapy and provided substantial training and supervision in this technique.

On the other hand, we tested only verbal disclosure, whereas most emotional disclosure studies have used writing rather than speaking, including one study in RA patients that found substantial benefits of written disclosure (Smyth et al. 1999). Written emotional disclosure may be more effective than verbal disclosure, but this needs to be tested directly. In addition, the content of what was disclosed or shared may not have been ideally suited to this technique. An initial examination of the topics disclosed by the two groups revealed that only 8% of the topics dealt with traumatic events, whereas 40% were about relationship problems, 25% dealt with RA or other health problems, and 11% pertained to bereavement. It is possible that disclosure of these latter three categories is less powerful than the disclosure and repeated processing of unresolved traumatic events, but because the latter were rare in this study, the effects of the technique were negligible.

The failure of a brief, 4-session protocol to have significant effects on a broad range of outcomes in RA patients is probably not surprising. RA is a disease that is chronic and that, over time, presents many challenges. If disclosure interventions are to have significant long-term effects in patients who have chronic disease, the interventions may need to be more intense and be accompanied by periodic booster sessions. The lack of any additional benefit of clinician assistance to disclosure suggests the need for additional refinement of emotional disclosure. We propose several ideas to enhance the effects of a clinician in the disclosure process. Clinicians might help patients more specifically identify and focus on experiences that have been particularly stressful and yet remain unresolved. They might more strongly encourage the patient to disclose and process the same stressor over repeated days, which has been shown to increase the effects of disclosure (Sloan et al. 2005). A clinician might also help the patient to spend much more time exploring the meaning of the experience or gently challenging the dysfunctional cognitions that often follow stressful experiences. Finally, it may be that teaching the patient skills, such as communication or assertiveness, will help them to resolve the stressful experience. These ideas await study.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Arthritis Foundation and, in part, by support from the Fetzer Institute. Preparation of the manuscript was supported by NIH grant R01 AR049059. The authors would like to thank Lisacaitlin Perri, Anne Aspnes, Robert Elliot, Greg Goldman, Victor Wang, Heidi Suarez, Paige Johnson, and Kimi Carson for their assistance and help in this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson KO, Bradley LA, McDaniel LK, Young LD, Turner RA, Agudelo CA, Keefe FJ, Pisko EJ, Snyder RM, Semble EL. The assessment of pain in rheumatoid arthritis: validity of a behavioral observation method. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1987;30:36–43. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KO, Keefe FJ, Bradley CA, McDaniel LK, Young LD, Turner RA, Agudelo CA, Semble E, Pisko EJ. Prediction of pain behavior and functional status of rheumatoid arthritis patients using medical status and psychological variables. Pain. 1988;33:25–32. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T, Carson KL, Darchuk AJ, Keefe FJ. The influence of social skills on private and interpersonal emotional disclosure of negative events. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2004;23:635–642. [Google Scholar]

- Angus LE, Levitt H, Hardtke K. The narrative process coding system: Research applications and implications for psychotherapy practice. J Clin Psychol. 1999;55:1255–1270. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1255::AID-JCLP7>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantley PJ, Waggoner CD, Jones GN, Rapaport NB. A daily stress inventory: Development, reliability, and validity. J Behav Med. 1987;10:61–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00845128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick JE, Stone AA, Smyth JM, Kaell AT. The feasibility and effectiveness of an expressive writing intervention for rheumatoid arthritis via home-based videotaped instructions. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:50–59. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly DA, Murray EJ. Cognitive and emotional changes in written essays and therapy interviews. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1991;10:334–350. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A, Sriram TG, Rajkumar S, Chandrasekar AN. Alexithymic characteristics in rheumatoid arthritis: A controlled study. Psychother Psychosom. 1989;51:45–50. doi: 10.1159/000288133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina PG, Borod JC, Lepore SJ. A meta-analysis of the effects of written emotional disclosure on the health outcomes of clinical populations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:629–634. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000138317.30764.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidron Y, Duncan E, Lazar A, Biderman A, Tandeter H, Shvartzman P. Effects of guided written disclosure of stressful experiences on clinic visits and symptoms in frequent clinic attenders. Fam Pract. 2002;19:161–166. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SB, Salkind NJ, Akey TM. Using SPSS for Windows: analyzing and understanding data. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LS, Rice LN, Elliott R. Facilitating emotional change. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH. Does expressive writing reduce health care utilization? A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:243–252. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe FJ, Block AR. Development of an observation method for assessing pain behavior in chronic low back pain patients. Behavior Therapy. 1982;13:363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JE, Lumley MA, Leisen JCC. Health effects of emotional disclosure in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Health Psychol. 1997;16:331–340. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler T. Stress and rheumatoid arthritis: A survey of empirical evidence in human and animal studies. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:655–663. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A, van de Ven JP, Schrieken B, Emmelkamp PM. Interapy, treatment of posttraumatic stress through the internet: A controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2001;32:73–90. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(01)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A, Rietdijk D, Hudcovicova M, van de Ven JP, Schrieken B, Emmelkamp PM. Interapy: A controlled randomized trial of the standardized treatment of posttraumatic stress through the internet. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:901–909. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K. Arthritis self-management leader's manual. Atlanta, GA: Arthritis Foundation; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel LK, Anderson KO, Bradley LA, Young LD, Turner RA, Agudelo CA, Keefe FJ. Development of an observation method for assessing pain behavior in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Pain. 1986;24:165–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenan RF, Gertman PM, Mason JH, Dunait R. The Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales: Further investigations of a health status measure. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1048–1053. doi: 10.1002/art.1780250903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenan RF, Kazis LE, Anthony JM, Wallin BA. The clinical and health status of patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:761–765. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EJ, Lamnin AD, Carver CS. Emotional expression in written essays and psychotherapy. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1989;8:414–429. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JC, Smarr KL, Buckelew SP, Stucky-Ropp RC, Hewett JE, Johnson JC, et al. Effects of stress management on clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1807–1818. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Emotion, disclosure, & health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Mayne TJ, Francis ME. Linguistic predictors of adaptive bereavement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:863–871. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter PT, Zautra AJ. Stressful life events’ effects on rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:319–323. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimon R, Laakso RL. Life stress and rheumatoid arthritis. Psychother Psychosom. 1985;43:38–43. doi: 10.1159/000287856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DL, Murray EJ. Emotional processing in cognitive therapy and vocal expression of feeling. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1994;13:189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Marx BP, Epstein EM. Further examination of the exposure model underlying the efficacy of written emotional disclosure. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:549–554. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Marx BP, Epstein EM, Lexington J. Does altering the writing instructions influence outcome associated with written disclosure? Behav Ther. 2007;38(2):155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;281:1304–1309. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, True N, Souto J. Effects of writing about traumatic experiences: The necessity for narrative structuring. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2001;20:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason BT, Brantley PJ, Jones GN, Dyer HR, Morris JL. The relation between stress and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Behav Med. 1992;15:215–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00848326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich PM, Lutgendorf SK. Journaling about stressful events: effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:244–250. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell MA, Byrne-Davis L, Dieppe P, Donovan J, Brookes S, Byron M, et al. Effects of emotional disclosure on psychological and physiological outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an exploratory home-based study. J Health Psychol. 2005;10:277–285. doi: 10.1177/1359105305049778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Burleson MH, Matt KS, Roth S, Burrows L. Interpersonal stress, depression, and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients. Health Psychol. 1994;13:139–148. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]