Abstract

Benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide (BPDE)-induced DNA adducts are a risk factor for tobacco-related cancers. Excision repair cross-complementing complementation group 1 (ERCC1) and excision repair cross-complementing complementation group 2/xeroderma pigmentosum D (ERCC2/XPD) participate in the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway that removes BPDE–DNA adducts; however, few studies have provided population-based evidence for this association. Therefore, we assayed for levels of in vitro BPDE-induced DNA adducts and genotypes of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the NER genes ERCC1 (rs3212986 and rs11615) and ERCC2/XPD (rs13181, rs1799793 and rs238406) in 707 healthy non-Hispanic whites. The linear trend test of increased adduct values in never to former to current smokers was statistically significant (Ptrend = 0.0107). The median DNA adduct levels for the ERCC2 rs1799793 GG, GA and AA genotypes were 23, 29 and 30, respectively (Ptrend = 0.057), but this trend was not observed for other SNPs. After adjustment for covariates, adduct values larger than the median value were significantly associated with the genotypes ERCC1 rs3212986TT [odds ratio (OR) = 1.89, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.03–3.48] and ERCC2/XPD rs238406AA (OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.41–0.99) and rs238406CA (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.45–0.89) compared with their corresponding wild-type homozygous genotypes. The results of haplotype analysis further suggested that haplotypes CAC and CGA of ERCC2/XPD, TC of ERCC1 and CACTC of ERCC2/XPD and ERCC1 were significantly associated with high levels of DNA adducts compared with their most common haplotypes. Our findings suggest that the genotypes and haplotypes of ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD may have an effect on in vitro BPDE-induced DNA adduct levels.

Introduction

In vivo DNA adducts detected in viable cells, such as peripheral blood lymphocytes, are a phenotypic marker for the biologic effects of both carcinogen exposure and host DNA repair capacity (1), because their detectable levels depend on not only levels of exposure that cause DNA adducts but also individual variations in response to such exposure, including cellular absorption, distribution, metabolic activation and detoxification and DNA repair capacity (2,3). Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from incomplete combustion of motor vehicles or power plants can lead to elevated levels of DNA adducts that are detectable in blood cells, such as benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide (BPDE)-induced DNA adducts (3,4). These adducts are repaired by the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway (5), which has several genes that perform a coordinated repair function (6). Genetic variation in the form of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of these NER genes can also modulate the levels of DNA damage in response to carcinogen exposure (7), if they affect their protein functions.

In vitro BPDE-induced DNA adducts can be used to study host DNA repair capacity in experimental settings. Because levels of in vivo-induced DNA adducts depend on the dose and duration of exposure, which are often poorly estimated in population-based studies, we developed an in vitro carcinogen-induced adduct assay to measure in vitro carcinogen-induced adducts under experimental exposure conditions (8). Because we showed that the in vitro BPDE-induced DNA adduct levels in that study were ≥1000 times those in vivo induced by smoking or other environmental carcinogens and because BPDE is an ultimate carcinogen, the detectable level of in vitro BPDE-induced DNA adducts in this assay reflects the host DNA repair capacity phenotype. In two early pilot case–control studies, we assayed BPDE-induced DNA adducts in cultured peripheral lymphocytes and found that these adducts can be a risk factor for tobacco-related cancers, such as lung cancer and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (8,9). These two pilot studies were later independently confirmed by much larger studies (2,10).

Excision repair cross-complementing complementation group 1 (ERCC1) and excision repair cross-complementing complementation group 2/xeroderma pigmentosum D (ERCC2/XPD) are two genes involved in the NER pathway (6) that, along with other genes (5), maintain genomic integrity by removing DNA lesions induced by ultraviolet light and other environmental carcinogens, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tobacco smoke (e.g. benzo[a]pyrene, which can be metabolized to form BPDE) (11). ERCC1 interacts with other genes, such as XPA and XPF in the NER pathway, to guide 5′-incision activity in DNA repair, and ERCC2/XPD is part of the transcription factor IIH that opens DNA strands around the site of the lesion (12) and thus produces interstrand cross-links that can be repaired by other NER proteins (6).

Because both ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD are located on chromosome 19 and participate in NER that removes bulky adducts, such as those induced by BPDE, we hypothesized that the genotypes and haplotypes of ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD genes determined the in vitro BPDE-induced DNA adduct levels in cultured primary lymphocytes of healthy people. Therefore, we performed a genotype–phenotype correlation analysis in healthy non-Hispanic whites who had been genotyped for SNPs of ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD and for whom BPDE-induced DNA adduct data were available. These individuals had been used as healthy controls in our previously published study (13).

Patients and methods

Study population

The study population for this genotype–phenotype correlation analysis consisted of 707 healthy non-Hispanic white cancer-free participants from an ongoing case–control study of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). These study participants had been recruited between 1995 and 2005 and were genetically unrelated visitors or companions of patients seen at MD Anderson Cancer center. The study was approved by our institutional review board and patient consent had been obtained, and the summary statistics about these participants were reported previously (2).

Cell culture and BPDE treatment and genotyping

The detailed methods used to obtain the in vitro BPDE-induced DNA adducts and the genotypes of study participants have been described elsewhere (2,13). In brief, 1 ml of whole blood from each participant was cultured in each of two T-25 flasks (each containing 9 ml of standard RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum and 112.5 μg/ml phytohemagglutinin). After 67 h of phytohemagglutinin stimulation, BPDE was added to the culture to a final concentration of 4 μmol/l, and lymphocytes for performing the assay were harvested after another 5 h incubation. The induced BPDE–DNA adducts were quantified by the relative adduct labeling (RAL) × 107. The SNPs of ERCC1 (MIM:126380) and ERCC2/XPD (MIM:126340) used in the analysis were ERCC1 NT_011109.15: g.18191871T>C (rs11615; p.Asn118Asn) and g. 18180954G>T (rs3212986) and ERCC2/XPD NT_011109.15:g.18120142C>A (rs238406; p.Arg156Arg), g.18135477G>A (rs1799793; p.Asn312Asp) and g.18123137 A>C (rs13181; p.Lys751Gln). These five putatively functional SNPs were chosen mainly because they were the most frequently studied to date and because their haplotypes were able to be inferred since they were all on chromosome 19. The detailed genotyping methods and experimental conditions have been described elsewhere (13).

Statistical analysis

The distribution of the DNA adducts was evaluated by plotting their percentiles. The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was used to test the normality of the DNA adduct distribution, and the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was tested by a goodness-of-fit χ2 test to compare the observed genotype frequencies with the expected genotype frequencies, assuming the study population was in the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. A non-parametric Wilcoxon two-sample test or non-parametric analysis of variance F test was used to determine DNA adduct distributions by the categorical variables such as age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption and family history of cancer. The linear trend of DNA adduct values was tested in variables with more than two categories (14). The linkage disequilibrium and R2 were computed for two-loci models to evaluate allelic association among SNPs (15).

We used multiple unconditional logistic regression analysis to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for high DNA adduct levels in participants with zero, one or two copies of the minor allele of each SNP. To detect interactions between smoking status and genotypes on the adduct levels, we used the Breslow–Day test to test homogeneity among ORs of genotype association with high DNA adduct levels stratified by smoking status, and the common ORs were estimated using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test (14).

For the haplotype analysis, we applied an expectation–maximization algorithm to infer haplotypes from the observed genotype data, because the current high-throughput genotyping techniques are not able to determine which two alleles are present at each locus for diploid individual and the haplotypes (i.e. combinations of alleles are transmitted from each of the two parents) of unrelated individuals are not known based on the available genotype information (16). In this study, we used the PHASE (version 2) program (17,18) to infer haplotypes. Details of the haplotype association analysis were described previously (19). In brief, we included the inferred haplotype in the unconditional logistic regression model to estimate haplotype-specific OR by using the most common haplotype as the reference group and collapsed all haplotypes with a frequency of <5% into one group. We used the likelihood ratio test to test the significance of the haplotype effect by comparing the logistic regression model that included haplotypes with the model containing the intercept only.

Finally, we used false-positive report probabilities (FPRPs) to detect false-positive associations (20) with the prior probabilities from 0.25 to 0.001. We considered FPRP <0.2 a noteworthy association for further validation. All statistical tests were two sided with P value <0.05 considered statistically significant and were performed using the SAS statistical software (version 9.13; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The characteristics of the study population in this study have been described previously (2). Of the 707 healthy non-Hispanic white participants, 183 were women and 524 were men; ages ranged from 20 to 85 years (mean, 56.1 years and median, 57 years). The levels of in vitro DNA adducts ranged from 0 to 1237 (RAL) × 107, with a median of 27 (RAL) × 107 in this study population. The raw and the log-transformed DNA adduct distributions were not normal (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.017, respectively), but highly skewed to high values.

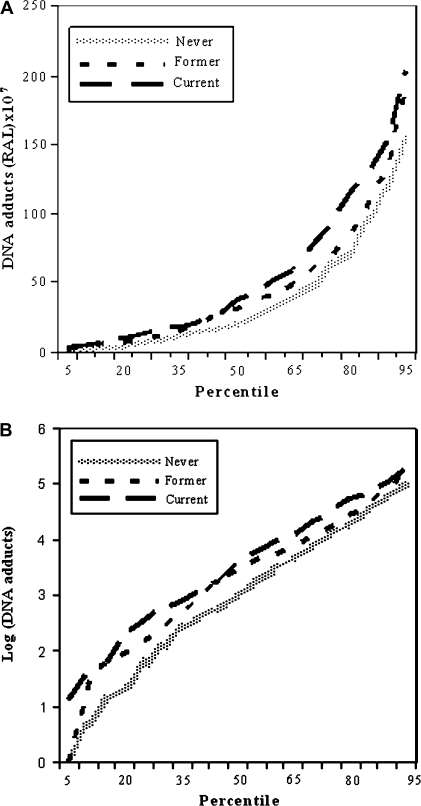

We first described the distribution of DNA adduct levels by age, sex, alcohol consumption, smoking status and family history of cancer. The levels of DNA adducts were not influenced by these covariates except for smoking status. The median DNA adduct levels in never, former and current smokers were 20, 31 and 38 (RAL) × 107, respectively. The linear trend test of increased DNA adduct levels in never to former to current smokers was statistically significant (P = 0.0107). Never smokers had significantly lower DNA adduct levels than did former smokers (P = 0.015) and current smokers (P = 0.001). To better describe the adduct distribution in three smoking subgroups, we plotted the percentiles of DNA adduct levels at the 5th, 10th, …95th by smoking status. The shape and the pattern of the percentiles of the never, former and current smokers were similar for the raw and log-transformed DNA adducts with current smokers having the highest value (Figure 1A and B). Thus, even though the levels of in vitro DNA adducts significantly increased from never to former to current smokers, the shapes of the DNA adduct percentile distributions were similar in these three groups (Figure 1A and 1B).

Fig. 1.

Plot of the 5th, 10th, … to 95th percentiles of DNA adducts in never (fine-dotted line), former (short-dashed line) and current (long-dashed line) smokers (A) and plot of the log-transformed DNA adducts percentiles in never (fine-dotted line), former (short-dashed line) and current (long-dashed line) smokers (B). The sample sizes for never, former and current smokers in these two plots were 331, 255 and 121, respectively.

Next, we examined the distribution of DNA adduct levels by the genotypes for each of the five SNPs (Table I). The median DNA adduct levels for the ERCC1 rs11615 and rs3212986 genotypes with zero, one and two copies of minor alleles were distributed similarly, with the highest median DNA adduct level seen in the genotype with two minor alleles and the lowest value seen in the genotype with either zero or one minor allele. The median DNA adduct levels were significantly higher in the ERCC1 rs3212986TT than in the ERCC1 rs3212986GG (P = 0.029). For the ERCC2/XPD rs238406, the median DNA adducts decreased as the copy number of the minor allele increased from zero to two. However, neither the trend test nor the two-sample Wilcoxon test results were statistically significant. The median DNA adduct levels of the ERCC2/XPD rs1799793 and rs13181 increased as the copy number of minor allele increased in genotypes. This linear trend was borderline significant for the ERCC2/XPD rs1799793 (Ptrend = 0.057).

Table I.

Median DNA adduct levels and genotypes of ERCC2/XPD and ERCC1

| SNP | No. (%) | Median (RAL × 107) | Pa | Pb |

| All subjectsc | 707 (100) | 27.0 | ||

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18123137A>C, rs13181 | ||||

| AA | 289 (40.9) | 22.0 | Reference | |

| AC | 330 (46.7) | 28.0 | 0.098 | |

| CC | 88 (12.4) | 30.5 | 0.075 | 0.114 |

| C allele | 506 (35.8) | |||

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18135477G>A, rs1799793 | ||||

| GG | 290 (41.0) | 23.0 | Reference | |

| GA | 335 (47.4) | 29.0 | 0.029 | |

| AA | 82 (11.6) | 30.0 | 0.079 | 0.057 |

| A allele | 499 (35.3) | |||

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18120142C>A, rs238406 | ||||

| CC | 207 (29.3) | 32.0 | Reference | |

| CA | 366 (51.8) | 24.0 | 0.133 | |

| AA | 134 (19.0) | 22.5 | 0.242 | 0.397 |

| A allele | 634 (44.8) | |||

| ERCC1, g.18180954G>T, rs3212986 | ||||

| GG | 399 (56.5) | 23.0 | Reference | |

| TG | 257 (36.4) | 29.0 | 0.529 | |

| TT | 50 (7.1) | 41.5 | 0.029 | 0.096 |

| T allele | 357 (25.3) | |||

| ERCC1, g.18191871T>C, rs11615 | ||||

| TT | 274 (38.9) | 25.5 | Reference | |

| CT | 324 (46.0) | 24.0 | 0.666 | |

| CC | 107 (15.2) | 34.0 | 0.074 | 0.082 |

| C allele | 538 (38.2) | |||

P value was obtained using the Wilcoxon two-sample test for the genotype of one or two copies of the minor allele compared with zero copies of the minor allele in each SNP.

Ptrend value was obtained using the non-parametric analysis of variance test for the trend among genotypes.

Two observations for genotype ERCC1 rs11615 and one observation for genotype ERCC1 rs3212986 in this sample were missing.

The genotype frequency and allelic association of the five SNPs are summarized in Table I. The genotype frequencies of these five SNPs in the study population were similar to those of 31 white cancer controls in the SNP500Cancer database and consistent, with 60 Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western European ancestry in the International HapMap Project and with cancer controls in other published studies (21–23) (data not shown). Among the five SNPs, ERCC1 rs3212986 and rs11615 had the highest correlation, with a correlation coefficient R2 of 42%. The five SNPs in our study also passed the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test, but the pairwise linkage disequilibrium tests for the five SNPs were all statistically significant, and the largest P value was <10−6 (data not shown). The significant linkage disequilibrium among these SNPs was accounted for by additional haplotypes analyses.

Because the in vitro DNA adduct levels were not normally distributed, we dichotomized the study participants into two groups using median DNA adduct levels as the cutoff point. As a result, 347 study participants with DNA adducts >27 (RAL) × 107 were classified as high-level adduct group and the remaining 360 with DNA adducts ≤27 (RAL) × 107 were grouped as low-level adduct group. The distributions of age, sex, alcohol use and family history of cancer in the high-level adduct group were comparable with those in the low-level adduct group, as also evidenced by the ORs and 95% CIs (Table II). However, the percentage of self-reported former and current smokers was higher in the high-level adduct group than in the low-level adduct group. For example, the ORs for high-level versus low-level adducts were 1.58 (95% CI = 1.13–2.19) and 1.53 (95% CI = 1.00–2.32) for former and current smokers, respectively. These results suggest that former or current smokers had a higher risk of having a high adduct level.

Table II.

Association between covariates and DNA adducts levels

| Covariates | DNA adducts (RAL × 107) |

Pa | OR (95% CI) | |

| >27, no. (%) | ≤27, no. (%) | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤56.5 | 169 (48.7) | 180 (50.0) | Reference | |

| >56.5 | 178 (51.3) | 180 (50.0) | 0.73 | 1.05 (0.78–1.41) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 85 (24.5) | 98 (27.2) | Reference | |

| Male | 262 (75.5) | 262 (72.8) | 0.408 | 1.15 (0.82–1.62) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 143 (41.2) | 188 (52.2) | Reference | |

| Former | 139 (40.1) | 116 (32.2) | 1.58 (1.13–2.19) | |

| Current | 65 (18.7) | 56 (15.6) | 0.013 | 1.53 (1.00–2.32) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Never | 141 (40.6) | 150 (41.7) | Reference | |

| Former | 56 (16.1) | 66 (18.3) | 0.90 (0.59–1.38) | |

| Current | 150 (43.2) | 144 (40.0) | 0.612 | 1.11 (0.80–1.53) |

| Family history of cancer | ||||

| No | 206 (59.5) | 219 (61.0) | Reference | |

| Yes | 140 (40.5) | 140 (39.0) | 0.691 | 0.94 (0.70–1.27) |

P value was obtained using the χ2 test for covariate frequency distributions in the high (adduct >27) and low (adduct ≤27) adduct levels.

We then studied associations between genotypes of ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD and high adduct levels (Table III). Individuals with the ERCC1 rs3212986TT were nearly as twice as likely to have high adduct levels than were those with the ERCC1 rs3212986GG, both before (OR = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.06–3.65) and after (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.03–3.48) adjustment for other covariates. For ERCC1 rs11615CC, the OR (1.56, 95% CI = 0.99–2.46) was borderline statistically significant before adjustment for other covariates. In contrast, participants with ERCC2/XPD rs238406AA or rs238406CA had a lower risk of having high-level adducts (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.45–0.89 and OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.41–0.99, respectively) compared with ERCC2/XPD rs238406CC after adjustment for other covariates.

Table III.

Association between ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD genotypes and DNA adduct levels

| SNP | DNA adducts (RAL × 107) |

Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | Pb | |

| >27, no. (%) | ≤27, no. (%) | ||||

| All participants | 347 (49.1) | 360 (51.0) | |||

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18123137A>C, rs13181 | |||||

| AA | 133 (38.3) | 156 (43.3) | Reference | Reference | |

| AC | 166 (47.8) | 164 (45.6) | 1.19 (0.87–1.63) | 1.18 (0.86–1.63) | |

| CC | 48 (13.8) | 40 (11.1) | 1.41 (0.87–2.27) | 1.39 (0.86–2.26) | 0.312 |

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18135477G>A, rs1799793 | |||||

| GG | 131 (37.8) | 159 (44.2) | Reference | Reference | |

| GA | 171 (49.3) | 164 (45.6) | 1.27 (0.92–1.73) | 1.21 (0.88–1.66) | |

| AA | 45 (13.0) | 37 (10.3) | 1.48 (0.90–2.42) | 1.44 (0.87–2.38) | 0.183 |

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18120142C>A, rs238406 | |||||

| CC | 117 (33.7) | 90 (25.0) | Reference | Reference | |

| CA | 169 (48.7) | 197 (54.7) | 0.66 (0.47–0.93) | 0.63 (0.45–0.89) | |

| AA | 61 (17.6) | 73 (20.3) | 0.64 (0.42–1.00) | 0.64 (0.41–0.99) | 0.039 |

| ERCC1, g.18180954G>T, rs3212986 | |||||

| GG | 182 (52.6) | 217 (60.3) | Reference | Reference | |

| TG | 133 (38.4) | 124 (34.4) | 1.28 (0.93–1.75) | 1.27 (0.92–1.74) | |

| TT | 31 (9.0) | 19 (5.3) | 1.95 (1.06–3.56) | 1.89 (1.03–3.48) | 0.050 |

| ERCC1, g.18191871T>C, rs11615 | |||||

| TT | 131 (38.0) | 143 (39.7) | Reference | Reference | |

| CT | 151 (43.8) | 173 (48.1) | 0.95 (0.69–1.32) | 0.95 (0.68–1.31) | |

| CC | 63 (18.3) | 44 (12.2) | 1.56 (0.99–2.46) | 1.51 (0.95–2.38) | 0.079 |

OR adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption and family history of cancer.

P value was obtained using the omnibus χ2 test with two degrees of freedom.

Because DNA adduct levels distributed similarly in former and current smokers (Wilcoxon two-sample test P = 0.16) but differently in former and never or current and never smokers (P = 0.015 or 0.001, respectively), we combined the former and current smokers into one group of ever smokers and performed the genotype association with risk of high-level adduct in the never and ever smokers. Even though all the ORs were not significant in the stratified analysis, the ORs of genotype ERCC1 rs3212986TT, rs11615CC and ERCC2/XPD rs238406AA and CA in never and ever smokers were similar to those of the overall study population (Table IV). Furthermore, the interactions between smoking status and genotypes were not significant in the stratified analysis because of the limited power of the small sample size in the subgroups. Because the common ORs estimated by the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test were comparable with those we reported in Table III, therefore, we used the overall study population for the haplotype analysis.

Table IV.

Association between ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD genotypes and DNA adduct levels (RAL × 107) in never and ever smokers

| SNP | Never smokers |

Ever smokers |

Pa | ORb | ||||

| >27, no. (%) | ≤27, no. (%) | OR (95% CI) | >27, no. (%) | ≤27, no. (%) | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Totalc | 143 (43.2) | 188 (56.8) | 204 (54.3) | 172 (45.2) | ||||

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18123137A>C, rs13181 | ||||||||

| AA | 57 (39.9) | 80 (42.6) | Reference | 76 (37.3) | 76 (44.2) | Reference | Reference | |

| AC | 62 (43.4) | 91 (48.4) | 0.96 (0.60–1.53) | 104 (51.0) | 73 (42.4) | 1.42 (0.92–2.20) | 0.222 | 1.18 (0.86–1.63) |

| CC | 24 (16.8) | 17 (9.0) | 1.98 (0.98–4.02) | 24 (11.8) | 23 (13.4) | 1.04 (0.54–2.01) | 0.192 | 1.40 (0.87–2.26) |

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18135477G>A, rs1799793 | ||||||||

| GG | 63 (44.1) | 89 (47.3) | Reference | 68 (33.3) | 70 (40.7) | Reference | Reference | |

| GA | 60 (42.0) | 79 (42.0) | 1.07 (0.67–1.71) | 111 (54.4) | 85 (49.4) | 1.34 (0.87–2.08) | 0.489 | 1.21 (0.88–1.66) |

| AA | 20 (14.0) | 20 (10.6) | 1.41 (0.70–2.84) | 25 (12.3) | 17 (9.9) | 1.51 (0.75–3.05) | 0.891 | 1.46 (0.89–2.40) |

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18120142C>A, rs238406 | ||||||||

| CC | 56 (39.2) | 47 (25.0) | Reference | 61 (29.9) | 43 (25.0) | Reference | Reference | |

| CA | 55 (38.5) | 105 (55.9) | 0.44 (0.26–0.73) | 114 (55.9) | 92 (53.5) | 0.87 (0.54–1.41) | 0.052 | 0.63 (0.45–0.90) |

| AA | 32 (22.4) | 36 (19.1) | 0.75 (0.40–1.38) | 29 (14.2) | 37 (21.5) | 0.55 (0.30–1.03) | 0.501 | 0.64 (0.42–1.00) |

| ERCC1, g.18180954G>T, rs3212986 | ||||||||

| GG | 75 (52.4) | 113 (60.1) | Reference | 107 (52.7) | 104 (60.5) | Reference | Reference | |

| TG | 58 (40.6) | 65 (34.6) | 1.34 (0.85–2.13) | 75 (36.9) | 59 (34.3) | 1.24 (0.80–1.91) | 0.794 | 1.29 (0.94–1.76) |

| TT | 10 (7.0) | 10 (5.3) | 1.51 (0.60–3.80) | 21 (10.3) | 9 (5.2) | 2.27 (0.99–5.18) | 0.517 | 1.91 (1.04–3.51) |

| ERCC1, g.18191871T>C, rs11615 | ||||||||

| TT | 51 (35.7) | 80 (42.6) | Reference | 80 (39.6) | 63 (36.6) | Reference | Reference | |

| CT | 67 (46.9) | 88 (46.8) | 1.19 (0.74–1.92) | 84 (41.6) | 85 (49.4) | 0.78 (0.50–1.22) | 0.197 | 0.95 (0.69–1.32) |

| CC | 25 (17.5) | 20 (10.6) | 1.96 (0.99–3.89) | 38 (18.8) | 24 (14.0) | 1.25 (0.68–2.29) | 0.332 | 1.52 (0.96–2.39) |

P value is the homogeneity test of the OR between never and ever smokers.

OR is the estimated common OR from the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test.

Total is the subgroup sample size. Former smokers had one missing value for ERCC1 rs3212986 and two missing values for rs11615.

Table V shows the association between ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD haplotypes and risk of high adduct levels. For the most common ERCC2/XPD haplotype AGA in the study, we found frequencies of 37.14 and 42.56% for the high- and low-level adduct groups, respectively (P = 0.011). All alleles of this haplotype were of low risk for each of the SNPs, according to the aforementioned genotype association analysis (Table III). For the second most common ERCC2/XPD haplotype CAC, we found frequencies of 29.57 and 22.93% for the high- and low-level adduct groups, respectively (P = 0.011). All alleles in this haplotype were of high-risk allele of each of the SNPs. Compared with AGA, high adduct levels were associated with the CAC (OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.16–2.05) and CGA (OR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.06–2.06) haplotypes after adjustment for other covariates. The association between ERCC2/XPD haplotypes and risk of high adduct levels was significant (the likelihood ratio test, P < 0.05, comparing the logistic regression model of haplotypes with the intercept-only model or the model adjusted for covariate variables). For ERCC1 rs3212986 and rs11615, haplotype TC was associated with an increased risk of having high adduct levels (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.00–1.66) compared with the most common haplotype, GT. The combined haplotypes with frequencies of <5% were also associated with an elevated OR of 2.79 (95% CI = 1.13–6.92) after adjustment for other covariates. Haplotypes inferred from the five SNPs in ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD are listed in Table V. Five haplotypes had frequencies of >5%, and the frequency differences between high- and low-level adduct groups were not statistically significant (P = 0.111). The haplotype AGAGT, which is composed of low-risk alleles of the five SNPs, was the most common haplotype in both high- and low-level adduct groups. The other four haplotypes were associated with an increased risk of high adduct levels; however, only the haplotype CACTC was associated with a significantly elevated OR of 1.66 (95% CI = 1.14–2.62) after adjustment for other covariates.

Table V.

Association between ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD haplotypes and DNA adduct levels

| Haplotypes | DNA adducts (RAL × 107) |

OR (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | Pb | |

| >27, no. (%) | ≤27, no. (%) | ||||

| ERCC2/XPD, g.18123137A>C, rs13181; g.18135477G>A, rs1799793; g.18120142C>A, rs238406 | |||||

| AGA | 247 (37.14) | 291 (42.56) | Reference | Reference | |

| CAC | 197 (29.57) | 157 (22.93) | 1.56 (1.17–2.07) | 1.54 (1.16–2.05) | |

| CGA | 125 (18.84) | 108 (15.73) | 1.43 (1.04–1.98) | 1.48 (1.06–2.06) | |

| CGC | 34 (5.17) | 51 (7.47) | 0.78 (0.49–1.26) | 0.80 (0.49–1.29) | |

| CAA | 29 (4.29) | 42 (6.07) | 0.80 (0.46–1.38) | 0.77 (0.44–1.33) | |

| Otherc | 33 (4.96) | 36 (5.21) | 1.19 (0.75–1.90) | 1.13 (0.70–1.82) | 0.011 |

| ERCC1, g.18180954G>T, rs3212986; g.18191871T>C, rs11615 | |||||

| GT | 396 (57.46) | 451 (62.98) | Reference | Reference | |

| TC | 176 (25.54) | 154 (21.50) | 1.29 (1.00–1.66) | 1.29 (1.00–1.66) | |

| GC | 100 (14.52) | 105 (14.66) | 1.09 (0.81–1.48) | 1.07 (0.79–1.45) | |

| Otherc | 17 (2.46) | 6 (0.83) | 2.83 (1.14–7.04) | 2.79 (1.13–6.92) | 0.019 |

| ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD combined | |||||

| AGAGT | 188 (31.02) | 231 (37.09) | Reference | Reference | |

| CGAGT | 83 (13.73) | 84 (13.46) | 1.23 (0.85–1.79) | 1.29 (0.88–1.89) | |

| CACTC | 104 (17.17) | 82 (13.25) | 1.65 (1.14–2.40) | 1.66 (1.14–2.42) | |

| CACGT | 50 (8.34) | 42 (6.82) | 1.49 (0.94–2.38) | 1.48 (0.92–2.36) | |

| Otherc | 180 (29.71) | 183 (29.34) | 1.28 (0.93–1.74) | 1.25 (0.91–1.72) | 0.111 |

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption and family history of cancer.

P values were calculated with use of the omnibus χ2 test.

Other haplotypes with frequency less than 5%.

Finally, we performed the FPRP analysis and found that under the assumption of a prior probability of 0.1, the FPRPs of ERCC1 and ERCC2 haplotypes yielded values of 0.17 and 0.11, respectively, suggesting that these findings were noteworthy (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, few studies have investigated the associations between in vitro-induced DNA adduct levels and genetic variations in NER genes in normal cells from the same individuals, although many studies have investigated the association between NER genotypes and cancer risk (11,24). In our current study, we found that ERCC2/XPD rs238406AA and CA, ERCC1 rs3212986TT, ERCC2/XPD haplotypes of CAC and CGA and ERCC1 haplotype TC were significantly associated with high levels of DNA adducts induced in vitro, suggesting that genotypes and haplotypes of ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD may determine the DNA repair phenotype in the cultured primary lymphocytes. This finding is consistent with our previous findings of a correlation between ERCC2/XPD variant genotypes and the host DNA repair capacity, as measured by a different cell culture-based assay in a much smaller sample of healthy control subjects (7). The strength of the current study is our inclusion of a large sample of healthy participants and the use of a cell culture-based assay for experimentally induced adducts that are relatively free of environmental exposure, such as tobacco exposure, because the in vitro-induced adduct levels are 1000 times that of in vivo induced by tobacco smoke (8). As a result, we were able to identify the associations between in vitro BPDE-induced DNA adducts (reflecting the host-cell DNA repair capacity) and haplotypes of ERCC1 and ERCC2/XPD.

The formation of DNA adducts in cellular DNA can be influenced not only by levels of exposure but also by individual genetic susceptibility. Matullo et al. (25) performed a stratified analysis and reported a significant OR of 3.81 (95% CI = 1.02–14.16) for the association between high levels of in vivo DNA adducts and the ERCC2/XPD rs13181CC compared with the ERCC2/XPD rs13181AA in never smokers. In our current study of in vitro-induced DNA adducts, we observed a borderline statistically significant OR associated with the ERCC2/XPD rs13181CC compared with ERCC2/XPD rs13181AA in never smokers. Although the study of Matullo et al. (25) measured in vivo adducts and ours measured in vitro adducts, we both concluded that ERCC2/XPD rs13181CC was associated with high levels of DNA adducts and this association was unrelated to smoking status.

Both in vivo (26) and in vitro (2,10) DNA adduct levels have been shown to be associated with cancer risk, and individual variations in the genes that are responsible for removing these adducts may also influence cancer risk (11,24); therefore, the in vitro-induced DNA adducts in normal lymphocytes may be considered a surrogate phenotype for cancer risk. However, obtaining phenotype data are time consuming and costly compared with obtaining genotyping data, although the latter data may be inconsistent in small studies. For example, in a meta-analysis, Manuguerra et al. (21) reported that ERCC2/XPD rs238406AA and CA compared with CC were associated with a high risk of skin cancer, whereas Lovatt et al. (27) reported that these genotypes were associated with a low risk of skin cancer. Therefore, additional information on the phenotype may help explain the discrepancies in these studies. For example, Crew et al. (23) reported that ERCC1 rs3212986AA increased the risk of breast cancer only in individuals with detectable polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon adducts in their peripheral blood. In our study, the rs3212986TT (equivalent to rs3212986AA in Crew’s study because we used reversed primers) was associated with high DNA adduct levels, and in previous epidemiologic studies (28,29), high levels of DNA adducts were associated with breast cancer risk; therefore, our result is consistent with Crew’s findings that DNA adduct levels can be used as a surrogate intermediate end point for breast cancer risk.

ERCC2/XPD is a key player in the NER pathway. Matullo et al. (22) determined the association between the haplotype GAT of ERCC2/XPD rs13181 and rs1799793 and ERCC1 rs11615 and risks of bladder cancer and leukemia by using a codominant or recessive model. We used the most common haplotype, AGA, as our reference group and found that haplotypes CAC and CGA were associated with an increased risk of high levels of DNA adducts. We believe that our fairly large sample size allowed us to detect relatively rare haplotypes in the study population.

Although cancer risk has been shown to be associated with reduced DNA repair capacity in a number of published studies (30–36), the roles of genetic and environmental risk factors may be more complex in cancer risk than in the DNA repair phenotype. However, the genetically determined DNA repair capacity may also determine the levels of induced DNA adducts. For example, in a study of 137 families (158 women with breast cancer and 154 sisters of these women), the levels of BPDE-induced adducts in lymphoblastoid cell lines obtained from these individuals were used as a surrogate tissue for measuring the DNA repair phenotype, assuming the genetically determined DNA repair phenotype would not be changed after the primary lymphocytes had been transfromed (36). The quartiles of the percent DNA repair capacity were inversely associated with breast cancer risk, i.e. the higher the levels of the BPDE-induced DNA adducts (or the lower the DNA repair capacity), the higher the cancer risk. We reported similar findings in a pilot study in which reduced host-cell DNA repair capacity, as measured by the reporter assay using BPDE as a DNA-damaging agent, was associated with breast cancer risk; in addition, variant genotypes of both ERCC2/XPD rs1799793 and rs13181 were predictive of the DNA repair capacity (34).

Because no change occurs in the amino acids in ERCC2/XPD rs238406 and ERCC1 rs3212986, linkage disequilibrium with adjunct functional variants of these two SNPs may be the reason for the observed effects on the phenotype. ERCC2/XPD rs238406, ERCC1 rs11615 and ERCC1 rs3212986 are adjacent on chromosome 19.3.2-3, and two other important cancer-associated genes, RAI and ASEI, are also located in this region (37,38). Therefore, further evaluation of the SNPs in this region is needed to identify other possible genetic markers for levels of induced DNA adducts or cancer risk.

There are limitations to our current study. First, we studied non-Hispanic white participants; thus, whether the same associations exist in other ethnic groups are unknown. Further studies with additional ethnic populations are needed. Second, the use of in vitro-induced DNA adducts as a surrogate measure of an individual’s DNA repair capacity may be less reliable because of large observed variations in the levels of DNA adducts. Some refining of the assay is needed for further validation studies.

In conclusion, we found that ERCC1 rs3212986TT, haplotypes CAC and CGA of ERCC2/XPD, TC of ERCC1 and CACTC of ERCC2/XPD and ERCC1 were significantly associated with high levels of induced DNA adducts. The FPRP tests further suggest that the findings of ERCC1 and ERCC2 haplotypes are noteworthy but need additional validation.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01 ES-11740 and R01 CA-100264 to Q.W., R25 CA-57730-16 to R.M.C. and P30 CA-16672 to MD Anderson Cancer center).

Acknowledgments

We thank Margaret Lung and Kathryn Patterson for recruiting the study participants, Jianzhong He for processing blood samples and Ping Chang for performing the adduct assays. We thank Dr Peter Kraft at Harvard School of Public Health for his advice on haplotype analysis and Ms Tamara Locke in the Department of Scientific Publications at MD Anderson Cancer Center for her scientific review for this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BPDE

benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide

- CI

confidence interval

- ERCC1

excision repair cross-complementing complementation group 1

- ERCC2

excision repair cross-complementing complementation group 2

- FPRP

false-positive report probability

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- OR

odds ratio

- RAL

relative adduct labeling

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- XPD

xeroderma pigmentosum D

References

- 1.Kyrtopoulos SA. Biomarkers in environmental carcinogenesis research: striving for a new momentum. Toxicol. Lett. 2006;162:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li D, et al. In vitro benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-induced DNA adducts and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5628–5634. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binkova B, et al. PAH-DNA adducts in environmentally exposed population in relation to metabolic and DNA repair gene polymorphisms. Mutat. Res. 2007;620:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farmer PB, et al. Molecular epidemiology studies of carcinogenic environmental pollutants. Effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in environmental pollution on exogenous and oxidative DNA damage. Mutat. Res. 2003;544:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephens JC, et al. Haplotype variation and linkage disequilibrium in 313 human genes. Science. 2001;293:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.1059431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reardon JT, et al. Nucleotide excision repair. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2005;79:183–235. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)79004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiao Y, et al. Modulation of repair of ultraviolet damage in the host-cell reactivation assay by polymorphic XPC and XPD/ERCC2 genotypes. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:295–299. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li D, et al. In vitro induction of benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxide-DNA adducts in peripheral lymphocytes as a susceptibility marker for human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3638–3641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li D, et al. In vitro BPDE-induced DNA adducts in peripheral lymphocytes as a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;93:436–440. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li D, et al. Sensitivity to DNA damage induced by benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxide and risk of lung cancer: a case-control analysis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1445–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumann AS, et al. Nucleotide excision repair as a marker for susceptibility to tobacco-related cancers: a review of molecular epidemiological studies. Mol. Carcinog. 2005;42:65–92. doi: 10.1002/mc.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volker M, et al. Sequential assembly of the nucleotide excision repair factors in vivo. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An J, et al. Potentially functional single nucleotide polymorphisms in the core nucleotide excision repair genes and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1633–1638. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. New York: Wiley Interscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxton AM. Genetic Analysis of Complex Traits Using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephens M, et al. A comparison of Bayesian methods for haplotype reconstruction from population genotype data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:1162–1169. doi: 10.1086/379378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens M, et al. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:978–989. doi: 10.1086/319501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephens M, et al. Accounting for decay of linkage disequilibrium in haplotype inference and missing-data imputation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;76:449–462. doi: 10.1086/428594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feigelson HS, et al. Haplotype analysis of the HSD17B1 gene and risk of breast cancer: a comprehensive approach to multicenter analyses of prospective cohort studies. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2468–2475. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wacholder S, et al. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:434–442. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manuguerra M, et al. XRCC3 and XPD/ERCC2 single nucleotide polymorphisms and the risk of cancer: a HuGE review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006;164:297–302. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matullo G, et al. DNA repair polymorphisms and cancer risk in non-smokers in a cohort study. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:997–1007. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crew KD, et al. Polymorphisms in nucleotide excision repair genes, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2033–2041. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berwick M, et al. Markers of DNA repair and susceptibility to cancer in humans: an epidemiologic review. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:874–897. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.11.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matullo G, et al. XRCC1, XRCC3, XPD gene polymorphisms, smoking and (32)P-DNA adducts in a sample of healthy subjects. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1437–1445. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veglia F, et al. Bulky DNA adducts and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovatt T, et al. Polymorphism in the nuclear excision repair gene ERCC2/XPD: association between an exon 6-exon 10 haplotype and susceptibility to cutaneous basal cell carcinoma. Hum. Mutat. 2005;25:353–359. doi: 10.1002/humu.20158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li D, et al. Aromatic DNA adducts in adjacent tissues of breast cancer patients: clues to breast cancer etiology. Cancer Res. 1996;56:287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang D, et al. Polymorphisms in the DNA repair enzyme XPD are associated with increased levels of PAH-DNA adducts in a case-control study of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002;75:159–166. doi: 10.1023/a:1019693504183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei Q, et al. DNA repair and aging in basal cell carcinoma: a molecular epidemiology study. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:1614–1618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei Q, et al. Repair of tobacco carcinogen-induced DNA adducts and lung cancer risk: a molecular epidemiologic study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1764–1772. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.21.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei Q, et al. Repair of UV light-induced DNA damage and risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:308–315. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matta JL, et al. DNA repair and nonmelanoma skin cancer in Puerto Rican populations. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003;49:433–439. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi Q, et al. Reduced DNA repair of benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-induced adducts and common XPD polymorphisms in breast cancer patients. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1695–1700. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu JJ, et al. Deficient nucleotide excision repair capacity enhances human prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1197–1201. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy DO, et al. DNA repair capacity of lymphoblastoid cell lines from sisters discordant for breast cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:127–132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goode EL, et al. Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes and associations with cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1513–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogel U, et al. Two regions in chromosome 19q13.2-3 are associated with risk of lung cancer. Mutat. Res. 2004;546:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]